Frida |

|||||||

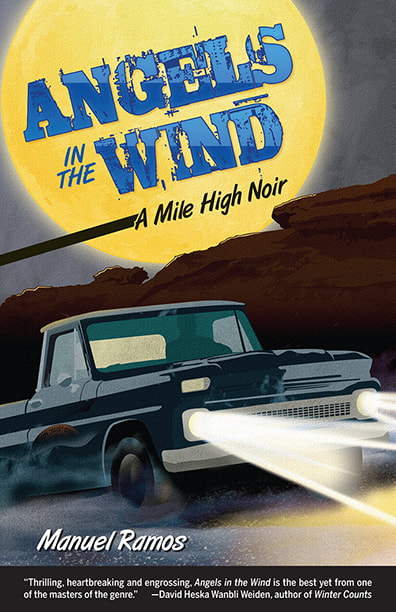

| excerpts_angels_in_the_wind__.pdf | |

| File Size: | 175 kb |

| File Type: | |

Read Part One

Read Part Two

The Beast of Cabo Rojo

Part Three

“It’s good to finally meet you, Professor,” Jones said, extending his right hand. “And it’s Detective Jones by the way.”

Lamboi glared at the proffered hand until Jones put it away. “I wish that I could say the same,” he said. “I’m not used to the police barging into my facility and questioning my employees.”

Lamboi turned his formidable glare on his assistant before whipping his chair around and soundlessly scooting away. “Follow me,” he said as he rolled down one of the corridors.

Annoyed, Jones hurried to catch up. “I didn’t just barge into your facility,” he said once he’d caught up to the professor and his chair. “I’m here on official police business.

Lamboi ignored him and continued past the doors of what were obviously offices and meeting rooms.

“Why don’t we just stop at one of these offices?” Jones asked. “What I need to ask should only take a few minutes. And, by the way, I have to admit that I’m impressed at how quiet that chair is, it makes absolutely no noise.”

“The offices are the domain of my assistant and the other drones,” Lamboi answered dismissively. “I prefer to conduct my business in the labs.”

Lamboi ignored the detective’s observation about the chair.

They passed through two sets of double-doors that opened automatically into what the professor described as the main lab. Then he spun the chair around so that he now faced Jones.

“So what business is it that brings the police to my facility unannounced and unwelcome?” Lamboi asked.

Jones hid his annoyance and sighed inwardly. “I apologize for the intrusion, Professor,” he said. “But I’m here investigating a series of murders…”

“And what does that have to do with me?” the professor asked shortly.

“Have you heard about the recent killings that have taken place right here in Cabo Rojo?” Jones asked.

“I’m a very busy man, I don’t have time for television or newspapers,” Lamboi sneered, “Or the garish goings-on of the internet.”

“I understand,” Jones said as he glanced around at the rows of stainless steel and plastic contraptions that filled the enormous lab. “Well it appears that these killings may have been committed by a very powerful creature—an ape in fact.”

Lamboi rolled his eyes, “There are no apes here,” he said.

Jones took out his notepad and flipped through the pages. “According to a Mr. Benitez, your facility received a donation of a large, adult chimpanzee…”

“Oh yes, that creature,” Lamboi sniffed. “I accepted that animal mostly as a favor to the desperate young man that runs that particular facility, but once I’d received it—and after a thorough examination—I’d concluded that the creature was far too damaged to be of any use to me.”

“So where is it now?” Jones asked.

Lamboi smirked. “Follow me,” he said as he spun his chair around and headed to the far end of the lab.

Jones followed.

Lamboi stopped his chair in front of a bank of stainless steel racks filled with glass containers of various sizes. “There’s your ape,” he said, indicating one of the large containers with a thrust of his chin.

Jones looked and was immediately repulsed and sickened. Floating in the fluid that filled one of the larger jars was an ape’s head, its face frozen in a perpetual scream.

“What happened to it?” Jones asked once he’d composed himself.

“I euthanized it, of course,” Lamboi said matter-of-factly. “As I said, it was far too damaged for it to be of any use to me.”

“Where’s the rest of it?”

“What’s left of its body is a pile of ashes in our on-site crematorium,” Lamboi said. Then he added with another smirk, “Feel free to take its head with you if it will help with your investigation.”

“No thanks,” Jones said, irritated with the professor’s condescending attitude.

“Very well then,” Lamboi said as he spun away and headed towards the doors through which they’d entered the lab. “In that case, I assume that our business here is finished.”

“Yeah, I guess it is,” Jones said as he snapped his notepad shut and put it away.

Lamboi led Jones back to the lobby where he and his personal assistant, Anna Vasquez, watched Jones exit through the front door and go out to the parking lot. Lamboi then turned his chair towards Anna Vasquez, his face twisted in rage.

Detective Perfecto Jones stepped out into the parking lot and walked the short distance to his car. The day had become overcast and Jones could hear the boom of thunder in the distance. The incoming weather matched his mood—this path of his investigation had basically come to an end—his theory, as crazy as it was, of a rogue ape being somehow involved in the killings in Cabo Rojo had ended in a pile of ashes, and a pickled head in a jar…

Suddenly a terrified scream came from inside the facility, followed closely by a loud thud and an even louder inhuman shriek that made the hairs on the back of Jones’ neck stand on end.

Jones yanked his pistol from its holster and ran back into the lobby of the facility…and into a nightmare!

Anna Vasquez’s body lay on the tiled floor in a rapidly spreading pool of her own blood. Her head was missing. Crouched over her, his gloved hands covered in blood, stood Professor Lamboi—his wheelchair lay on its side.

“Hold it right there, Professor!" Jones yelled. “Don’t move!”

Lamboi slowly turned his head, looking first at Jones’ raised gun, and then directly into Jones’ eyes. He smiled. “It was your fault, you know,” he said calmly. “She knew how I value my privacy. She knew better than to allow the police to come nosing around in my business.”

Outside, thunder rumbled and announced the approaching rainstorm with a dramatic series of bass drumrolls. Inside, the two men ignored it and kept their eyes locked together.

“It was only a matter of time before you were caught, Professor,” Jones said evenly.

“Don’t you want to know why? Or how?” Lamboi asked.

“I can find all of that out once I have you cuffed and in a cell,” Jones answered. “Right now what I want is for you to lay face down on the floor right there.”

Professor Lamboi glanced down at the slowly congealing pool of Anna Vasquez’s blood. “That can be quite messy,” he said.

Jones quickly took a glance at the blood too, just as a sharp crack of thunder exploded outside.

Lamboi leapt at the detective, reaching for the pistol in Jones’ hand. Jones squeezed the trigger but at this close range he couldn’t tell if he’d hit Lamboi or not. As the two men struggled over the gun, Jones was able to fire off two more shots but they went wide; the bullets burying themselves in the fancy receptionist’s desk. Lamboi then succeeded in knocking the gun out of Jones’ hand, nearly breaking the detective’s wrist in the process.

The thunder, now accompanied by brilliant flashes of lightning and the staccato sound of rain, continued to boom outside even as the two men inside savagely fought for the upper hand.

Jones, although he was larger than the professor and trained in hand-to-hand combat by the military, could tell, to his horror, that he was losing the fight. He latched onto the professor in a futile bid to wrestle him to the ground, but Lamboi managed to knock his hands away and shove him back. Jones sprawled onto his back, tearing away the professor’s blood-spattered lab coat as he fell.

Jones quickly raised himself up onto his elbows; the lab coat still clenched tightly in his hand, and looked around wildly for the professor.

At first, Jones’ mind was incapable of processing what he was seeing, and he just sat there propped up on his elbows trying to will his eyes to see reason. But his eyes betrayed him, because what they insisted on seeing was the professor’s head attached to the thickly muscled body of an ape!

“Like it?” Professor Lamboi asked, puffing out his chest and standing a little straighter. “Quite by accident I found that the amalgamation of chemicals in the ape’s body not only negated its natural ability to reject foreign tissue while maintaining a more or less uncompromised immune system, but the ape’s physiology was such that it seemed to welcome and even embrace multi-tissue interfaces while still remaining capable of fighting off the typical microbial invaders that cause infection. I considered it a miracle that this animal found its way to my facility. Due to my unfortunate disability, I’d already conducted a massive amount of research on the probability of performing a successful head transplant, and after that it was a matter of programming my surgical robots to perform the surgery.”

Jones stood up on legs that felt like rubber, and tried to keep his hands from shaking. “I have no idea what you just told me,” he said. “But is all that the reason you killed those people—for some kind of research?” Jones inched his way to the door as he spoke.

“Oh no,” Lamboi said. His eyes, feverish and shiny, followed Jones’ every move. “Even though the surgery was a complete success, I’d made one slight miscalculation…I had opted to keep the ape’s brain stem intact, it’s the reptilian part of the brain that controls base functions such as breathing. Unfortunately this eventually had the effect of somehow transferring the creature’s substantial, and for the most part, uncontrollable rage to me. In essence, its madness became my madness.”

Jones could make out a viscous line of drool leaking from the professor’s mouth and making its way down to his chin. When he looked back up to the professor’s eyes, all he could see were the dizzying depths of his insanity. In desperation Jones threw the lab coat at Lamboi and ran out into the storm.

The wind and rain lashed at his face, blinding him. He fumbled for his car keys, but his trembling hands wouldn’t cooperate and he dropped them on the ground. Jones heard the building’s door open behind him, and he turned to see the monster that used to be Professor Lamboi framed in the open doorway. Lamboi tore the gloves from his hands and flexed his powerful fingers.

“Your head will make a fine addition to my collection, Detective!” Lamboi called out before bursting into maniacal laughter that ended in a series of ape-like hoots and shrieks.

“My God no!” Jones gasped before turning and running across the parking lot and out through the still open gate.

At first Jones ran along the road, but then he heard the beast that had been Professor Lamboi gibbering and shrieking insanely behind him, and he plunged into the darkening forest in a panic.

Jones soon lost his bearing as he crashed through the trees and underbrush, his breath coming in ragged gasps. He had hoped to somehow get to the lighthouse, with its promise of shelter and people, but now he had no idea where he was going and he was too afraid to care. All he knew was that every instinct, every sense, indeed every fiber of his being screamed at him to get away!

Another flash of lightning lit up the sky, burning the image of the forest into monochromatic relief before his eyes, and revealing the glint of water in its strobe. Jones stumbled towards it.

He’d almost made it when he was forced to stop short. He thought that he had been headed towards a beach and the possibility of more people, but instead he now found himself standing on a muddy knoll that abruptly ended right in front of him. The hurricane must have washed away a chunk of the land here, and created a ragged outcropping that jutted out about ten feet above the water.

Jones searched the immediate area desperately as he tried to figure out which way to go, but it was no use—he was trapped.

Jones turned towards a blood-curdling shriek that came from the forest behind him just as a bolt of lightning silhouetted the nightmarish figure of the professor hurtling towards him!

Professor Lamboi barreled into the detective, wrapping his long, powerful arms around his torso as both men flew off the knoll and into the water ten-feet below.

The shock of hitting the cold water caused Lamboi to loosen his grip on the detective who, despite having the wind knocked out of him, managed to kick and flail his arms until he found himself free and swimming towards the surface.

Once he’d broken through to the surface and had filled his lungs with air, Jones nervously scanned the surrounding water for any sign of Lamboi.

A few moments later, sputtering and coughing, the professor surfaced about three feet away from where Jones was effortlessly treading water. The detective could see that Lamboi was having trouble staying afloat.

“Help me you fool! Help me!” The professor coughed.

Jones could only stare.

Professor Lamboi let out a terrible shriek and reached out with one of his long, monstrous arms in an effort to grab Jones, but the sudden movement only caused him to momentarily sink beneath the water. He soon returned to the surface again, his dark eyes wide with fear. “What’s wrong?” He asked. “I can’t stay afloat!”

“An ape’s muscle-mass is too dense for it to swim,” Jones recited, remembering being told this earlier in his investigation. “It would just sink.”

“No!” Professor Lamboi spluttered past a mouthful of seawater, his arms beating frantically at the water around him. “Save me! You must save me-e-e…” And then he sank beneath the waves one last time, his pale face still visible for several feet under the sea’s covering before disappearing into the depths.

Jones looked away, noticing for the first time that the storm had passed. He saw lights and heard distant music coming from a strip of beach about 50 yards away and tiredly made his way in that direction. Back to the world of comparative normalcy, and away from the final watery resting place of the Beast of Cabo Rojo.

Read Part One

The Beast of Cabo Rojo

Part Two

The boat, operated by a young college intern, took him to a battered dock attached to a small “r” shaped island. He was met at the dock by a trim, studious-looking young man who introduced himself as Andres Benitez; a primatologist.

“Do you mind if we stay out here by the dock?” Benitez asked. “We have several scientists involved in a number of very sensitive studies right now, and it would help if we kept the human presence down to a minimum.”

Jones nodded as he produced his notepad and pen. “Sure, no problem,” he said. “This shouldn’t take long.”

“Great,” Benitez responded enthusiastically. “What little we had in the way of shelter or meeting space was blown out to sea by the hurricane. We have no permanent structures on the island since no one is allowed to stay overnight anyway.”

“And I imagine that’s also to minimize the human footprint here,” Jones said, while writing in his notepad.

“Exactly,” Benitez agreed. “Now, how may I help you officer?”

“Detective, actually,” Jones corrected. “I’m looking for a chimpanzee that I was told was donated to your facility. This was before the hurricane struck.”

“Oh yes, I remember that entire episode quite clearly,” Benitez said, a note of sadness creeping into his voice. “At the time we considered it to be a rescue type of thing.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well the zoo had literally run out of money, and so was rapidly trying to divest itself of all of its large animals,” Benitez explained. “The last of these was a very large adult chimpanzee that they had acquired as a donation from a lab.”

“So then you guys decided to take the chimpanzee in,” Jones said.

Benitez nodded. “It was a mistake,” he admitted. “The poor ape was severely traumatized and, even though you couldn’t initially tell by looking at him, his overall health had to have been compromised by all of the chemicals and drugs that were coursing through his bloodstream.”

“So where is the chimp now?” Jones asked.

Benitez sighed. “Look, you have to understand,” he said emphatically. “No other facility would take him in. We were hoping to temporarily house him in one of the large steel cages that some of our scientists eat their meals in while observing the monkeys, but he was too big and powerful. He destroyed two of the cages before we were able to sedate him. And even sedation was tricky since he didn’t react as expected, again, probably due to all of the chemicals already in his system.”

“Just how did he react?”

“The normal dose of sedative for an ape his size had no effect on him rather than causing him to become increasingly agitated and belligerent. The doses had to be increased to dangerous levels just to put him out.”

“So where’s the chimpanzee now?” Jones asked again.

“Wait, let me finish,” Benitez said. “The longer the chimpanzee stayed here, the angrier it became, with the vocalizations of the island’s resident monkeys seeming to irritate it. In turn its own screeches and its pounding on the floor and bars of the cages disturbed the monkeys to the point of ruining at least several months’ worth of scientific observation, entries, theories…

“I’m responsible for the 1,000 Rhesus Macaque monkeys that reside here, as well as for the students and scientists that study them.”

“Did the chimpanzee ever hurt any of the people here?” Jones asked. “Did it escape during or after the hurricane? Is it possible that it got out of its cage and swam back to Puerto Rico? Is that what you’re trying to hide here?”

“What? No!” Benitez insisted, before taking out his handkerchief and wiping his face. It had grown much warmer since their meeting started, and standing out in the open didn’t help things. “A chimpanzee’s muscle density would cause it to sink like a stone—it would have drowned.”

“So then where is it now?” Jones insisted.

Benitez sighed. “I gave it to a research lab back in Puerto Rico,” he stated dejectedly.

“I have no idea what happened to him after that, and I didn’t want to know.”

“Give me the name and address of that lab,” Jones insisted, writing it down in his notepad as quickly as Benitez recited it. His heart almost skipped a beat when Benitez told him that the lab was located in Cabo Rojo.

“A few more things,” Jones said still writing in his notepad. “Is a chimpanzee smart enough to erase its footprints from a crime scene? Can it be taught to do that? Can it be kept as a pet and taught to kill people?”

Benitez looked confused for a moment, but then answered the questions. “A chimpanzee is indeed smart enough to cover its tracks, but to answer your second question as well, it wouldn’t normally see the benefits of doing something like that, and so it would have to be trained to do so.”

“And the last question?”

“This reminds me of an Edgar Allen Poe story that I once read in high school, ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue,’ where an ape that was being kept as a pet commits murder…”

“So it is possible?” Jones pressed.

“Well, that was a work of fiction of course, but chimpanzees are often kept as pets,” Benitez said. “Unfortunately their owners soon find out that once a chimpanzee reaches adulthood, it becomes too unpredictable and dangerous to be safely kept as a pet any longer. As far as being taught to kill, I honestly don’t know. But a full-grown chimpanzee, and in my opinion especially the chimpanzee in question, is physically more than capable of killing a human being with its bare hands.”

After the short return trip from Monkey Island to the main island of Puerto Rico, Jones received a call from his captain: another headless body had been found in Cabo Rojo.

As soon as Jones pulled up to the crime scene, he was met there by a nearly frantic Sergeant Acosta.

“You seem to be spending more time working homicide scenes than recovering stolen vehicles,” Jones called out as he exited his vehicle.

Sergeant Acosta nodded and wiped his sweaty face with a handkerchief. “Yes,” he acknowledged. “The hurricane has pushed many of us out of our comfort zones.”

Jones clapped the Sergeant on his broad back good-naturedly. “Very true,” he agreed.

Acosta led him to the part of the forest that faced the grounds of the Los Morillos lighthouse; known simply as El Faro to the locals. The usually well-kept grounds of the lighthouse were littered with debris left behind by the hurricane. Volunteers armed with little more than hand tools toiled under the hot sun in an effort to clear away the mess. It was one of these volunteers, Sergeant Acosta explained, that had found the body partially hidden under an unruly pile of twigs and branches.

“It is like the others,” Acosta pointed out once they’d reached the body. “It has no head.”

Jones nodded absently as he searched the area near the body for clues—especially footprints.

“Perhaps the gargoyle has taken it?” Sergeant Acosta asked nervously.

Jones sighed. “If you want to remain a part of this investigation, Sergeant, then I suggest that you stop the superstitious nonsense.”

“Yes sir,” the Sergeant answered dejectedly.

Jones pointed at the area around the body. “No clear footprints,” he said. “Just like at the other crime scene, it looks as if they’ve been brushed away.”

Sergeant Acosta took a quick glance around and nodded in agreement.

“Apparently an ape would have no reason to do that on its own,” Jones added quietly as if in afterthought.

“Huh? I didn’t hear you, detective,” Acosta said.

“Never mind,” Jones said. “Arrange for this body to join the others in the refrigerator truck, and see if you can get Dr. Rivera to perform the autopsy.”

“Yes, sir,” the Sergeant said as Jones started walking back to his car. “Where can I say you’ll be if anyone asks?”

“Tell them that I’m with my wife and kids,” Jones said before driving away.

At the hotel where his family had taken refuge after the hurricane, Detective Jones sat on the room’s king-sized bed and used the remote to mute the sound on the television.

“The boys are finally asleep,” Jones’ wife Marisol said as she entered the room. “I wish I had half their energy!”

They laughed quietly as she climbed onto the bed and sat next to him. Jones rubbed her back, and she wiggled her toes in pleasure.

“How’s the house holding up?” She asked.

“About the same,” Jones answered. “I just had to take a break from that hammock!”

Marisol laughed again, “I can imagine,” she said. “Well at least tonight you can get a decent night’s sleep.”

Jones straightened up and put his hands in his lap. “I’m not sure I can sleep anyway,” he said. “This case I’m working on doesn’t make any sense.”

“You mean the gargoyle?” Marisol asked playfully.

Jones groaned and rolled his eyes, and then he sighed. “I hate to say this,” he said. “But I’m starting to wonder whether it is a gargoyle after all.”

Marisol laughed lightly, her eyes sparkling in the dim light. “I was only kidding, Perfe,” she said, using his nickname.

Jones sighed again. “I know,” he said. Then he told her about his search for an elusive chimpanzee that may also be a killer.

“I was so sure about the chimpanzee,” Jones said. “But at both crime scenes it looked like someone had deliberately tried to cover up the footprints there, and I was told that chimpanzees wouldn’t normally do anything like that, they would have to be taught to do that.”

Marisol bit her bottom lip as she processed the information that her husband had just told her. “Is it possible that someone is helping the chimpanzee hide its tracks?”

“I considered that,” Jones said. “But apparently this particular chimpanzee is too aggressive and dangerous to be led around on a leash or trained to do anything.”

Jones rubbed his suddenly cold hands together, “And I kept getting this feeling that I was being watched.”

Marisol placed her hand over both of his. “Like you told me happened to you sometimes during the war?”

Jones shook his head. “No, no. Not like that exactly,” he explained. “It wasn’t just a feeling of being watched—I could feel a terrible anger coming from whoever was watching me from the shadows. I can barely explain it. Actually the feeling may have been closer to hate than anger…it may have even been evil. Look, the hairs on my arms are standing straight up while I’m thinking about it.”

Marisol reached out and gently smoothed the hairs on one of his arms. “You’re tired, Perfe,” she said. “Looking after the house, sleeping on a hammock, this crazy case…you’ll figure it all out soon, you always do. All you need now is a good night’s sleep.”

Then, what started out as a goodnight kiss, ended in sweet lovemaking, and afterward he did have a good night’s sleep.

In the morning, Jones found himself on the road to Cabo Rojo before the sun had fully risen. He drove with the windows open, the air redolent with the astringent scent of the sea. In the distance roosters crowed while the distinct two-tone call of the Coqui tree frogs competed with the trilling singsong of the birds just waking from their nocturnal slumbers.

The drive down to Cabo Rojo was relatively uneventful. Jones nodded appreciatively at the road crews and volunteers still removing debris from the roads or directing traffic around the detours.

The drive through the forest to get to where the lab was located was a different matter altogether. The paved road soon disappeared, replaced by a pitted and rutted disaster that in some places was choked with near impenetrable barriers of hurricane engendered junk and debris. Jones had to backtrack and/or go off-road several times before coming to a well-maintained turn-off that led to a tall chain-link fence topped with razor wire.

Jones continued along the road running alongside the fence until he reached a small, circular clearing and a gate with a callbox mounted next to it.

Jones climbed stiffly from the confines of his vehicle and stretched the kinks out of his back and joints. As he was stretching, he looked around and took stock of his surroundings. The clearing and the entire area as far as his eyes could see, was surrounded by thick forest. Whereas earlier Jones had been able to smell the sea and had been serenaded by birds and frogs, the deep, jungle-like foliage that now surrounded him seemed to have the effect of dampening sound and blocking whatever breeze could have refreshed him, so that it seemed that in this place the day suddenly grew hot, humid and unnaturally quiet.

Jones then peered through the fence at the strange dome-like buildings beyond. The sight was surreal—three large dome-shaped buildings connected by what appeared to be external passageways. At one end of the compound stood what looked like a huge microwave antenna, pointed accusingly at the perfectly azure sky. If it wasn’t for the perfectly normal looking parking lot, the whole thing would have looked like something out of a science-fiction movie.

Perfecto Jones pressed the sole button on the callbox, and after a moment, a woman’s voice answered.

“Lamboi Labs.”

Jones identified himself and then added, “I believe someone from my office may have called you last night to let you know that I was coming?”

Several more moments passed, and just when Jones was about to press the button again, the voice returned.

“Yes, and I remember telling that person that the professor is not accepting visitors at the moment.”

“This isn’t a ‘visit’, Jones insisted. “And if the professor prefers, I can go back and get a warrant that would then involve more officers and which would also then be much more intrusive, I assure you.”

After a few more moments, the voice came through again. “Please drive up to the main building.”

This last direction was followed by a loud click, and a whirr as the gate retracted. Jones climbed back into his car, drove past the gate, and into the parking lot, where he parked next to the only other vehicle there.

As he exited his car again, Jones was met by a sharply dressed woman carrying a clipboard. “Detective Jones,” he introduced himself with his hand outstretched.

The woman, Jones assumed that she was the same person that he’d spoken with through the callbox, looked at his hand and avoided shaking it by gripping her clipboard even tighter. “Follow me,” she said curtly before turning around and disappearing through the doorway of the building.

Jones lowered his hand, shrugged, and followed her inside.

The inside of the building was much cooler than Jones expected, but it wasn’t uncomfortable. As the woman with the clipboard led him towards a semi-circular receptionist’s desk, Jones looked around at the ultra-modern, almost futuristic, décor.

“How long has this place been here?” Jones asked once they’d stopped at the receptionist’s desk.

The woman that had led him into the building took a seat behind the desk, and placed her clipboard carefully on top of it before answering. “The main building, this one that we’re in, was built six years ago. The other two, and the rest of the compound, were added later on, so the entire complex is relatively new.”

Jones gave a low whistle. “Six years? I never knew that this place existed until recently.”

“The professor values his privacy.”

“I guess so,” Jones said as he pulled out his notepad and referred to the notes he’d taken down during his research earlier. “And that would be Dr. Gustavo Lamboi?”

“Yes. He owns and runs this facility.”

“I see,” Jones said, tapping his pen on the notepad. “And who are you?”

“My name is Anna Vasquez,” she answered. “I’m Professor Lamboi’s personal assistant.”

Jones took a quick look around, “I’d like to speak to Dr. Lamboi,” he said.

“He knows that you’re waiting,” Vasquez said. “He will be joining us momentarily.”

Jones nodded.

“And he prefers to go by the title of professor,” she added.

“Professor of what?” Jones asked.

“Before his accident, he was a professor of spinal trauma and surgery at the medical college,” she answered. “His research led the way to making great gains in the areas of robotic and laser surgeries, not to mention his groundbreaking work in the areas of stem cell implementation, immunology, and micro-surgery.”

Jones stopped writing in his notepad and looked at her. “You really admire the, uh, professor,” he said.

A blush stole its way quickly over face and neck. “Of course I admire him,” Anna said. “He is a great man; a genius! I was his student at the college, and that’s where he first hired me as his research assistant. Once he received the grant to build this facility, he brought me onboard as his personal assistant.”

“That’s a lot of assisting,” Jones said, shutting his notepad and trying to keep the sarcasm out of his voice.

Anna Vasquez skewered him with a sharp glance. “What are you implying?” She asked sharply.

“Nothing,” he said casually. “Nothing at all. I, uh, did notice the unique shape of the buildings here…”

“The dome shape of the buildings make them virtually hurricane-proof,” Vasquez explained. “The high winds have nothing to grab onto, and so ensure that damage is kept at a minimum. Each building and exterior passageway also utilizes a mostly gravity-based drainage system that automatically funnels potential flood-water away from the structures and out into the nearby mangroves…”

“Mangroves?”

“Mangrove trees are notorious for their ability to tolerate flooding and even the occasional saturation of seawater, Mr. Jones.”

Surprised, Jones abruptly turned around to see who had just spoken to him.

“I am Professor Lamboi, owner and administrator of this facility.”

Keep a look out for the conclusion in Part III.

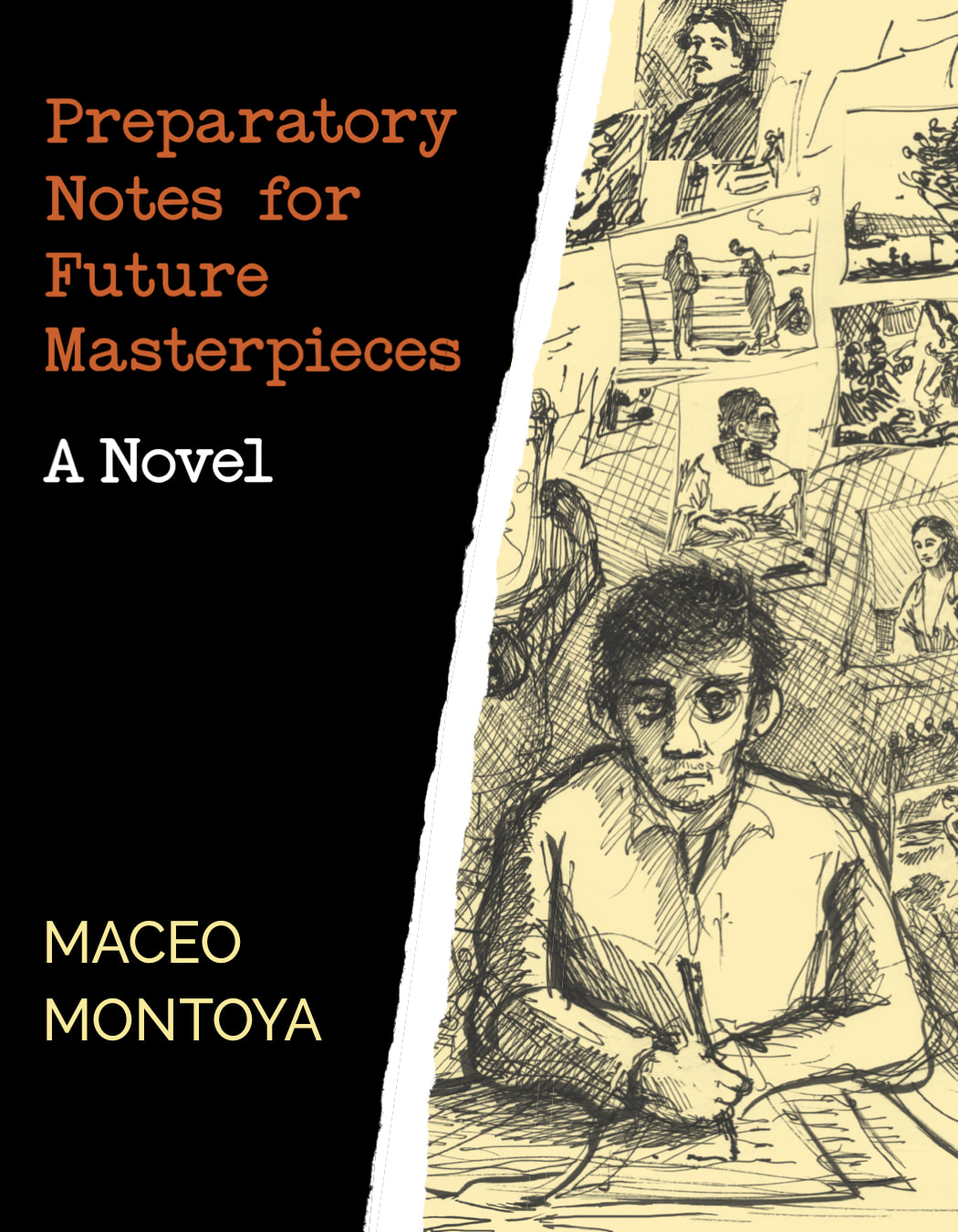

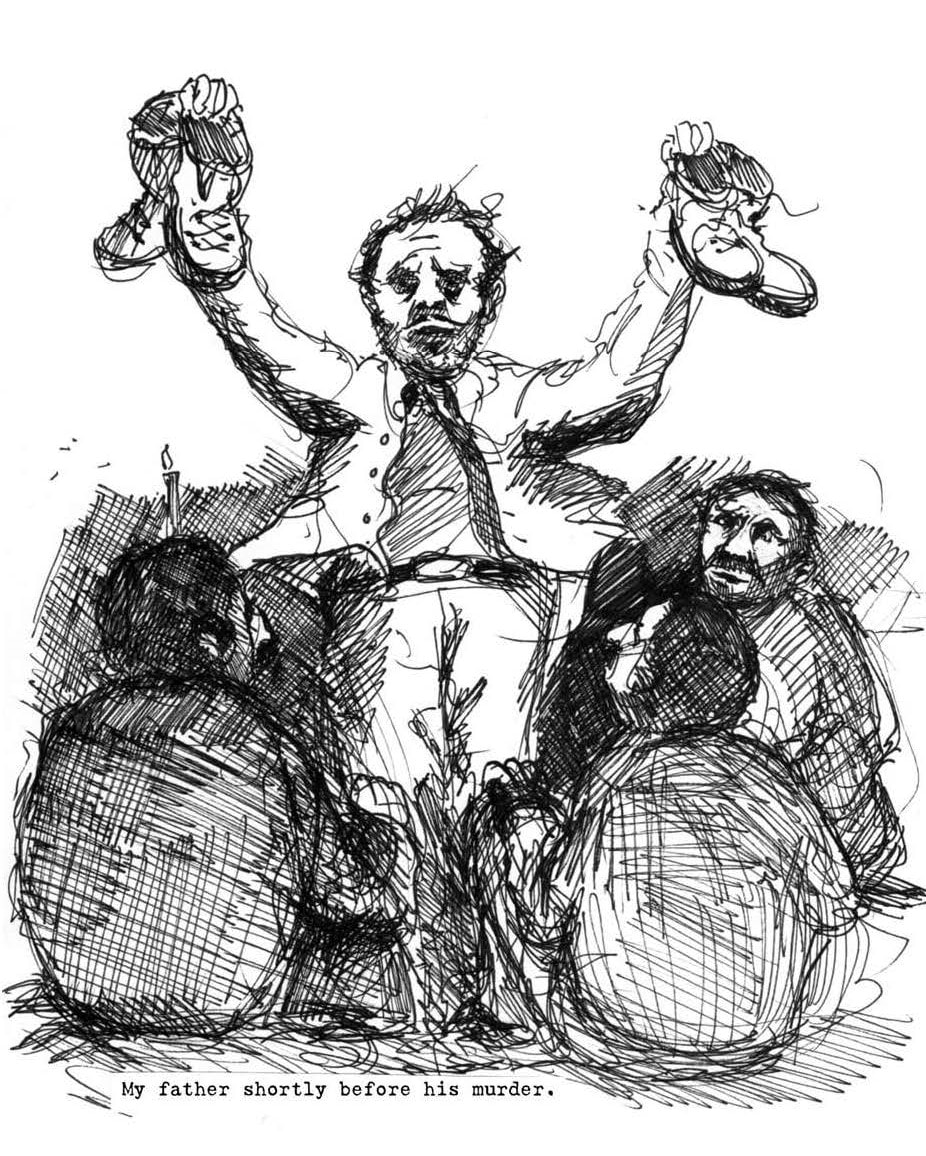

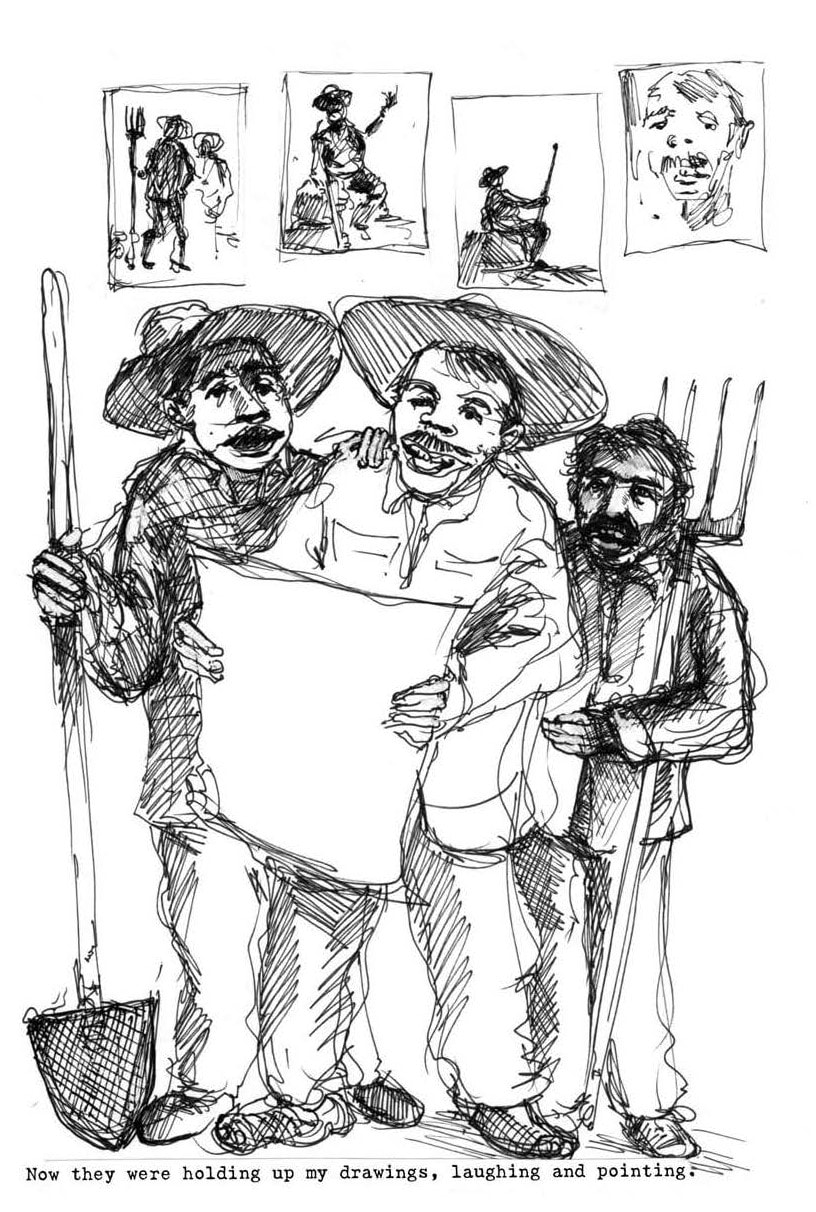

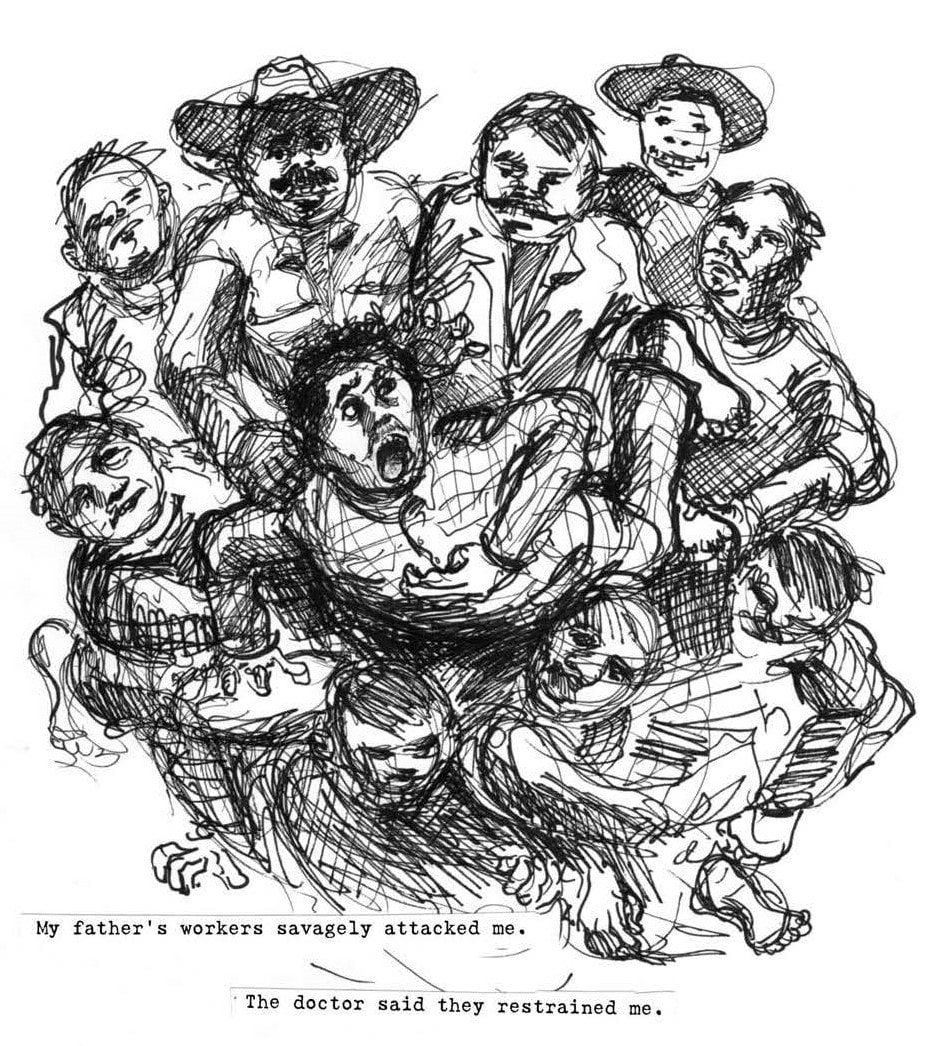

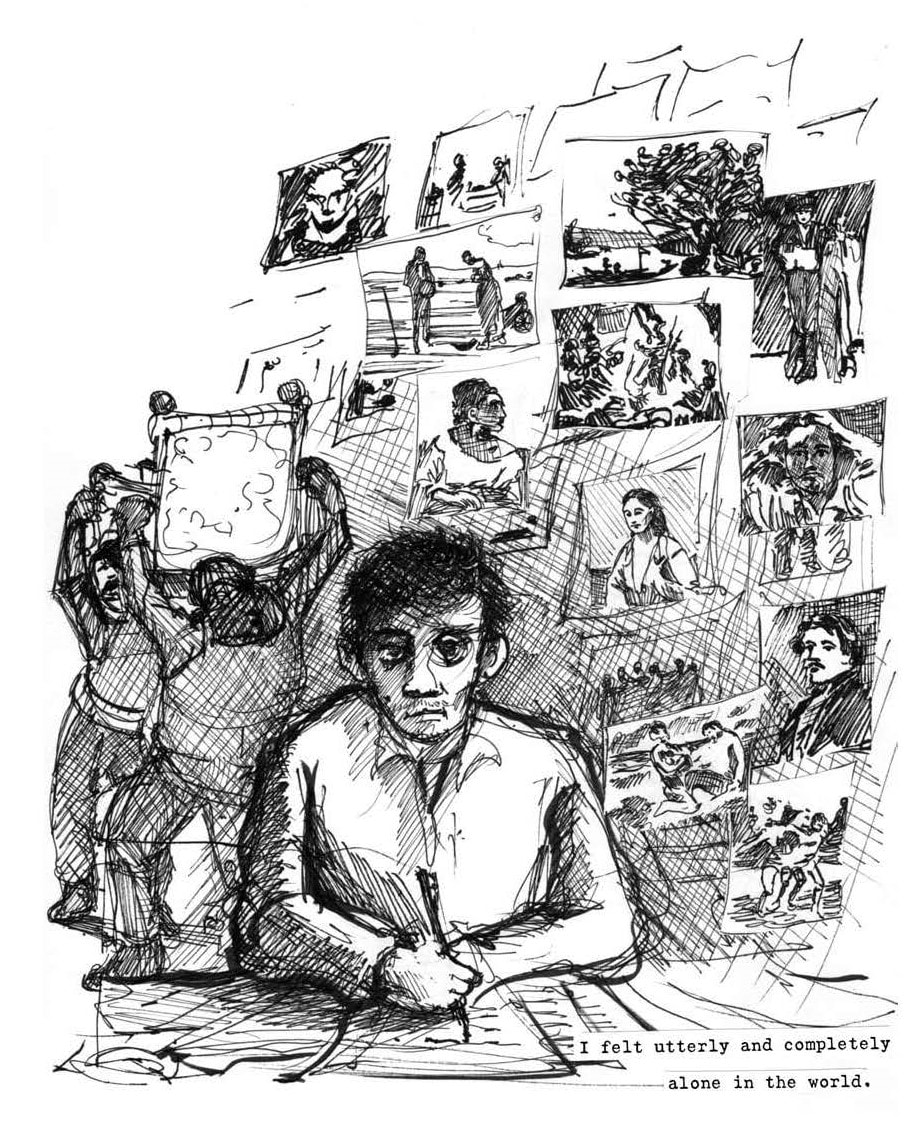

An excerpt from

Preparatory Notes for

Future Masterpieces

by Maceo Montoya

Cristina barked at me, “El pasaje tuyo is longer and more dramatic.”

“Has leído El Anarchist Cookbook?” I asked. “If you want dramático, maybe slip in a paragraph or two from that.”

She moved on to the dresses. “Este no me queda bien. These dresses aren’t suited for a mature figure.”

Sofía said, “Ay, por favor. You’re just jealous because our figures are fifteen years younger.”

Cristina stopped speaking to her and that meant she wouldn’t stop chatting me up. In truth, I hated the teal taffeta dresses and thought they suited Cristina much better. With the exception of a few hours on Sunday that included Mass, she wore miniskirts and midriffs everywhere and, after getting her chichis done, she liked showing off her cleavage—which the dress definitely did.

By the second fitting I was tired of looking at dresses and hearing about Cristina’s date for the boda: a paleta man from Potosí. So, I decided to convince her to let me feel her chichis. The fitting area of Betty’s Bodas was crowded and stuffy and I whispered to her that we should step outside for some air. Then I slid around the corner, to the quieter side street, and as innocently as possible, said, “All this looking at women in dresses made me curious about your operation, Cristina. And I was wondering if I can touch them.”

She stared at me a moment. “If you give me one good reason for wanting to, I’ll let you.”

“I’ll give you two. First, I’ve never felt chichis other than my own. Second, I’ve never seen falsas.”

“They’re not falsas,” she sniffed. “They just needed a little lift.”

“Why not just get a good bra?”

“You’ll understand someday.”

I doubted it, but when she straightened her back and said, “Ándale,” I reached out and touched them. They felt like plastic baggies filled with Jell-o.

Cristina lifted her shirt and bra and quickly showed me the scars. “¿Qué piensas?” she asked.

“Pues...in my humble chichi opinion, the scars look painful, pero las chicas look nice and lifted.”

The day of the gran ceremonia toda la familia met at mi abuelita’s to pick up boutonnieres and corsages. Mi Tía Gisela had a summer cold, but she didn’t let it stop her from walking around snapping fotos of everyone. Her fotos always came out blurry, off centered and with our heads chopped off, so no one bothered to pose.

Abuelita was following Freddy around the house trying to convince him “to groom himself.” His reddish-brown hair fell to his shoulders in waves and he brushed it frequently and was careful about what he put in it. Women loved it, pero abuelita thought it made him look uncouth and insisted he tie it back, at least for Mass.

“Do it for me, hijo,” she pleaded as he went from room to room, inspecting himself in every mirror.

“Pero, mami, Natalia won’t recognize me.”

“Then, por lo menos, shave your face. Natalia should see what you really look like.”

“Oh, she’s seen me...”

“No quiero saber, Freddy. Listen to me, please. You’ll thank me years from now.”

We were just about out of time when abuelita and Freddy went into the blue baño and closed the door. When he emerged with his hair in a ponytail, without his mustache and forked-beard, we couldn’t believe it. Abuelita beamed and Freddy walked out of the house like a chamaquito forced to attend his big brother’s wedding.

We got to the church and smashed into the back room where everyone congratulated each other on how lovely they looked. Cristina was wearing a pair of aqua-colored contacts that matched her dress. Abuelita took one look at those eyes and said, “¡Ay, Cristina, qué susto!”

When the first few notes from the organ flooded the cathedral, I joked, “No turning back now,” and Natalia burst into tears. Sofía and I shared a we’ll laugh about this later look, then we grabbed our partners—Natalia’s cousins, shy as feral cats—and we headed up the aisle. After taking our places in the pews, we watched Natalia in her weeping moment of glory. When she got close enough to see Freddy’s face, she did a double take and Tía Gisela’s flash went off.

As soon as everyone settled into the hard creaky benches, the priest began the old New Mexican tradition of roping the novios together with a large wooden rosary that resembled a lasso.

I whispered to Sofía, “Ya vez, that’s what marriage is.”

When the novios knelt, we saw someone had taken Kiwi’s white shoe polish to the bottom of Freddy’s shiny rental shoes. The left said Help and the right said Me. While the congregation attempted to stifle their laughter, Gisela started a stream of squeaky sneezes. Her gringo-date kept passing her tissues as if they were love notes, not snot catchers. The novios got to their feet and the sin vergüenza Cristina began motioning for Natalia to look at the bottom of Freddy’s shoes. Instead, Natalia snuck a peek at her own and, finding no chicle or puppy poop, shot Cristina a watchale! look.

It didn’t take long for the ceremonia to lag. Prayers, preaching, promises to do this and not do that. I was ready for the fiesta. We’d already had a few, including an underwear party where we bought Natalia new chones, ate taquitos and played silly games for silly prizes. I knew that, in the hall adjacent to the church, kegs were being tapped, wine uncorked and champagne chilled. It was easy to imagine la cocina full of aromas and comadres arguing over who put too much salt in the frijoles and how picante the chile should be.

The wedding finally concluded with a big beso where Freddy bent Natalia back like they were doing the quebradita. Then we marched into the hall that Natalia’s friends had decorated with blue-green streamers and purple paper flowers. Tío Freddy let down his hair and I traded my heels for Vans.

The mariachis started with “Un rinconcito en el cielo.” They invited abuelita to sing a few songs with them and, after applauding louder than anyone, Sofía and I tried sneaking a beer to the bathroom. Tía Gisela, who should have been paying attention to her gringo-date, intercepted us.

I said, “It’s for Carolina.”

Our older cousin never drank, but Gisela just said, “In the baño?”

“Yeah, she doesn’t want anyone to see her taking a swig.”

I looked at Sofía and followed her eyes to Carolina, who was in a bright red dress talking to a group of people not far from us.

“Hand it over,” Gisela said, holding out her germy hand.

“¿Qué te importa?” I snipped.

“¿A ti te importa if I tell your mamá?”

We handed it over.

After dinner the novios knelt again for La Entrega, which must have been uncomfortable con panza llena. It’s supposed to release the newlyweds to their new life and, though some people stage it at end of the night, my familia does it right before the dance, to release the novios to their fiesta. As the band tuned up, los compadres roped Freddy and Natalia together with a sandalwood rosary and gave them la long bendición while people tossed money onto Natalia’s long white train. Con el último amen Gisela tossed a dirty green bill that slid down Natalia’s silky back.

As soon as the money was scooped up the band began to play. They waited about an hour for people to start feeling buzzed and generous before they started The Dollar Dance. I paid $4 to dance with Natalia and $3 to dance with Tío Freddy. He told me he liked my Vans, then he picked me up and spun me around. Sofía said it was dumb for me to dance with Natalia and I said what was dumb was her pinche statement. Natalia looked so stunning with her heavily outlined eyes and her blue-black hair pinned up that some men paid twice to dance with her, making The Dollar Dance nearly as long as the wedding.

Freddy’s best man pinned dollars on my tío’s tux, but everyone in Natalia’s line pinned the bills on her themselves. When her train was covered men began carefully pinning money on the front of her dress. It made Natalia’s mother nerviosísima and she told the band, “Wrap it up, chicos!” She probably cost the novios fifty bucks.

After all the bills were unpinned, one by one, Natalia danced with Freddy a couple of times before Gisela singlehandedly “stole the bride.”

To no one in particular, her gringo-date said, “Is that a Mexican tradition?”

I was standing next to him and answered, “No, it’s more of a Southwestern scheme to get more loot. One that happens to imitate the kidnappings latinos have become infamous for.”

He stared at me and excused himself to get a drink.

Gisela led Natalia to a coatroom at the back of the hall where she would voluntarily stay sequestered. Knowing everyone would just be removing more money from purses, pockets and wallets, when Cristina followed, I went too. It didn’t take long for Gisela to pop open a $200 bottle of champagne intended for the newlyweds’ private party and, while flattering Natalia and filling her glass, she snapped fotos.

In between songs we could hear the bandleader: “Oye, the bride is still missing! Come and make a contribution to Comadre Yolanda so we can raise enough ransom to bring Natalia back!”

The coatroom hosted more fotos, more drinks and, at last, the band announced, “Ya está. Tenemos el dinero suficiente and the novios are $453 richer!”

By the time Yolanda tiptoed into the room in impossibly high heels, Natalia couldn’t have subtracted five from ten and she just hiccupped uncontrollably when Yolanda handed her a wad of cash. She passed it Cristina, who started counting.

“What’d you do to her, Gisela?” Yolanda asked, nodding at Natalia.

“¿Yo?’ Gisela sniffled, ‘pues, nada...”

They argued, Natalia hiccuped and Cristina, who’d counted the money twice, asked, “What’d you do, Yolanda? Slip a fiver in your bolsa?”

“How dare you!” Yolanda glared at Cristina as if she were a cucaracha.

“We all heard the band say the crowd raised $453.”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” Yolanda scoffed. “I needed to make change.”

A new argument ensued that Natalia interrupted with her silence. Everyone stared at her.

“Hiccups are gone,” she giggled.

Cristina and Yolanda shuffled her back to the dance and the band said, “Let’s welcome the bride back! Let’s hear it for Natalia.”

The crowd cheered. But Natalia’s mamá took one look at her daughter and cried, “¡Válgame dios! Natalia missed half the dance and, look at her, she’s as clumsy as a cow!”

Natalia probably should have sat down and had some water, pero she fell into Freddy’s arms, in the middle of a Cumbia, and away she went. He had no idea his wife’s head was spinning like a top when, holding her hand above her head, he spun her halfway around so they both faced the same direction. He held her tightly for a few pulses, her back against his chest and his hand on her stomach. Then he gave her a media vuelta so she faced him again. Finally, he twirled her three hundred and sixty degrees with the left hand, a quick one eighty with the right, another with the left and, with two hundred eyes upon her, Natalia puked like a cat.

I turned to Cristina and said, “¿Sabes qué? Forget the dinero—better to be a bridesmaid.”

Whenever Paloma, Crucito, and I got so sick Mom couldn’t heal us with her herb-filled cabinets, an egg, or Vaporú, we had to wait for the week to hurry up, so Dad could take us on a trip to visit our doctor who lived in another country. We crossed the border to a familiar place called Tijuana, Baja California, México. Estados Unidos Mexicanos—the United Mexican States—said the large shiny Mexican pesos in Spanish. With her miracle stethoscope, our doctor’s Superwoman eyes and Jesus hands always found where the illness hid.

As our father drove into Tijuana, the city looked like an expensive box of crayons. Fuchsia and lime green colors hugged buildings. Dad parked our shiny Monte Carlo the color of caramelo on the third floor of a yellow parking facility, and we walked down a cement staircase and crossed onto Avenida Niños Héroes. Then, we went up peach marble stairs and entered our doctor’s waiting room.

On the weekends, patients from faraway cities like Los Ángeles and San Bernardino came to see La Doctora. Judging from the looks of some of the patients’ faces, they were there to see the doctor’s husband, who was a dentist. They made the perfect couple—the doctor and the dentist—for both their Mexican and American patients. The doctor, a tall woman with smoky eye shadow, looked directly into her patients’ eyes when she spoke. Not like some American doctors in the U.S. who didn’t look at Mom because she only spoke Spanish.

On one of those doctor visits, I heard the dentist, a tall, burly man with a mustache that looked like a broom, speak English on the telephone with a patient. “John, you need to come in, so I can take a look at your tooth.”

Another time I saw an elderly gringo, waiting for his wife, seeking the dentist’s services. That’s when I realized the other side was expensive for them too.

When we were done at the doctor’s office, our next stop was El Mercadito on the other side of the block on Calle Benito Juárez. Churros sprinkled with sugar and cinnamon in metal washtubs rested on the shoulders of vendors. Fruit cocktail and corn carts were closer to the sidelines of streets, so passersby could make full stops and buy their favorite pleasure bombs to the taste buds.

During summer visits to Tijuana, Paloma ate as much mango as she wanted because fruit was affordable in México. My weakness was corn. And even if I felt sick, I always looked forward to eating a cup of corn topped with butter, grated cheese, lemon, chili powder, and salt. Mexican corn didn’t taste like the sweet corn kernels from a tin can—Mexican corn tasted like elote.

Approaching El Mercadito, dazed bees were everywhere. Mother warned us about not harassing bees. Because according to Mom, bees were like us—like butterflies. “Without bees, our world would not be as beautiful and delicious. Bees are sacred, and without them, we wouldn’t exist. Paloma and Chofi, please don’t ever hurt bees,” Mom said as we walked by our fuzzy relatives and nodded in agreement.

The smell of camote, cilacayote, cajeta, and cocadas added to the blend of enticing smells at the open market, where we roamed with buzzing bees peacefully. Colorful star piñatas and piñata dolls of El Chavo, La Chilindrina, and Spiderman hung along the tall ceiling, and the familiar smell of queso seco filled the air heavy with delight. Wooden spoons, cazos made of copper, molcajetes, loterias, pinto beans, Peruvian beans, and tamarindo provided such a wide selection of merchandise vendors didn’t have to fight over customers. Politely, they asked, “What can I give you?” or “How much can I give you?” as we walked by.

In Tijuana, street vendors sold homemade remedies for just about anything imaginable. “This cream here will alleviate the itch that doesn’t let your feet rest,” and “For a urine infection, drink this tea,” vendors hollered. And then there were the funny concoctions, for which even I, a girl my age, didn’t believe their miracle powers: “For the loss of hair, use this cream that comes all the way from the Amazon Islands.”

Hand in hand with our familia, Paloma and I walked the streets of Tijuana with our sandwich bag full of pennies and nickels. We gave our change to children who extended their little palms up in the air. Mom would take a bag full of clothing and find someone to give it to, which I never understood, because most people on the streets dressed just like us, from the pharmacists to children wearing school uniforms.

Once, when we were walking in Tijuana, Paloma and I saw a man with no legs riding what looked like a man-made skateboard instead of a wheelchair. Our eyes agreed; the man needed the rest of our change.

Besides the rumors about Tijuana being a dangerous place, nothing ever happened to our car or Mom’s purse. In Tijuana, doctors had saved Crucito’s life because my parents knew, if they took Crucito to a hospital in the U.S., he might not come out alive because American doctors wouldn’t try hard enough for a little brown baby like my little brother. In Tijuana, our parents spoiled us with goodies and haircuts at the beauty salon. And I felt bad for Americans who couldn’t afford a doctor and didn’t have a good doctor or a dentist like ours in El Otro Lado—on the Mexican side. Pobrecitos gringos.

“. . . Girls--to do the dishes

Girls--to clean up my room

Girls--to do the laundry

Girls--and in the bathroom . . .”

—The Beastie Boys, “Girls”

Because we couldn’t afford a fancy steam iron, Mom was very practical. Instead of using a plastic spray bottle, she sprayed Dad’s dress shirts, including other garments with her mouth. She gracefully spat on each garment lying on el burro.

Ironing was always an all-nighter that seemed endless and agonizing. I hated ironing Dad’s Sunday dress shirts—or anything, requiring special care and Mom’s supervisory instructions.

There were two chores I hated most about being a girl: ironing and washing someone else’s clothes.

The piles and piles of Dad and Mom’s dress clothes on top of our clothes seemed endless. (Thank God Father worked in construction or else long sleeve dress shirts would have added more to the pile). As soon as Mom started setting up el burro—the ironing board—in what should have been half a dining room, but instead we used as a bedroom, I began my whining.

“Mom, but why do Paloma and I have to iron Dad’s clothes?”

“¡Ay Sofia! You’re so lazy!”

“It’s just that I don’t understand. I don’t wear Dad’s clothes. Why us?”

“Sofia, are you going to start? That mouth! ¡No seas tan preguntona! You always ask too many questions! You always talk back! That tongue of yours. Where did you learn those ways‽”

When I nagged, my mother’s facial gestures expressed her disappointment, and she turned her face away from me. What had she done to deserve such a lazy daughter like myself? With a cold bitter laugh, Mom responded, “Because he’s your father,” which I never understood.

Having to live in apartments also meant we needed to fight over laundromat visitation rights. If anybody left their clothing unattended and the dryer or washer cycle ended, Paloma had to spy to check if anyone was coming, and I’d quickly take out the clothing and place it on a folding table. I’d throw our clothes inside the washer or dryer, and then we’d run to our apartment; otherwise, we’d be washing and drying all day.

When we moved from Vista to San Marcos, that’s when I noticed chores strategically favored the man in our family. For instance, we girls never carried out the trash like Dad—just heavy laundry baskets mounted with dirty clothes. To me, mowing the lawn didn’t look difficult at all. It looked super easy and fun.

How to Mow the Long Green Grass

By Chofi Martinez

1) Check the lawn for Crucito’s toys, Dad’s nails,

and any other sharp objects, including rocks.

2) Add gasoline.

3) Turn the lawn mower’s switch ON.

4) Press on the red jelly like button several times.

5) Pull the starter a couple of times.

6) Push the lawn mower with all your human strength.

If I could mow the lawn like a boy, at least I could be outside and listen to the singsong of finches, watch white butterflies flutter through the garden, greet and wave at neighbors passing by, and stare at the endless blue sky. But instead of Paloma and me mowing the lawn, Dad dropped us off at the laundromat on Mission Avenue next to the dairy to wash and fold everything from heavy king-sized Korean blankets to Dad’s dirty and not so white underwear. Bras and underwear were the most embarrassing garments to dry, especially when red stained or not so new underwear fell to the ground, while we checked the clothes in the dryer. If an undergarment accidentally fell, it’s not like we could ignore it and just leave it there when it was clear we were watching each other. For us, if someone looked at our bra or underwear, it was as if they were looking at our naked bodies. It was equivalent to watching feminine hygiene commercials in front of boys or even worse—Dad. Oh my God! ¡Trágame tierra!

Sometimes, when we barely had enough quarters and single dollar bills to spare in our imitation Ziploc bag, I’d window shop at the vending machine with its snacks and cigarettes then stare and admire the package labels with the bright oranges and mustardy yellows.

While we waited for the washer to end, we sat on the orange laundromat chairs (bolted to the ground in case anyone tried to steal them, I figured). My eyes wandered—at the graffiti, the announcements, the tile floor that needed a broom and a mop, the Spanish newspapers with the sexy ladies with their back to the readers wearing a two piece—a thong and high heels and the constant drop off and pick up of wives and daughters.

Swinging my feet back and forth out of boredom, I stared at the dryer’s circular-glass door with the thick-black trim, where garments would slowly go round and round and round and round, painting a picture of a vanilla and chocolate ice cream swirl, which was like meditating in front of a TV screen. Another dryer gave form to a motley of colors from the palette of Matisse’s bright yellows, blacks, oranges and greens Ms. Watson, my art teacher, had lectured on. And then, the dryer came to a full stop, and the colors—the burgundy red and thorny pink roses and the stoic lion—on heavy blankets took their true forms in need of folding.

Mom and Dad were always working for our dream house. In his early twenties, dressed in slacks and a tie, José Armando, our real estate agent, came to our apartment and talked to my parents about becoming homeowners. He sat patiently for what felt like hours translating endless paperwork. José Armando, Tijuana born with Sinaloa roots, grew up in Carlsbad, “Carlos Malos.” He smelled like a professional, and the heaviness of his cologne and starchy clothes filled our small kitchen and living room long after he was gone. Our real estate agent felt like familia.

“Helena and Francisco, the contract states that if you complete all the renovations within a year, the bank will approve the loan. You can move in now, but the house is not in living conditions.”

“But Jose Armando, I’m sure you’ve heard stories--what if the gringo doesn’t keep his promise?” Mom asked our real estate agent.

“Helena, please trust me. Mr. Stoddard is a good man and will not back out of the deal because he signed the contract,” José Armando assured Mom the owner would follow through. “You know Francisco more than I do. Your husband is going to make the house look like a palace—like your dream home. Helena, the property even has a water well. You can add the roses, calla lilies, and fruit trees you’re looking for in a property. And, most importantly, you won’t have to commute from Vista to San Marcos anymore.”

Where Dad and Mom came from, waiting periods to build a house didn’t exist; people didn’t need permits to build a home made from adobe or blocks. In the U.S., however, my parents had to settle for a fixer-upper Dad could mend in no time with the help of family and friends.

When José Armando finally struck a deal with the owner, it took Dad a whole year to claim the house on 368 West San Marcos Boulevard as our own. After Dad came home from working construction all day, he’d work at home. Mom must have had sleepless nights when Father agreed to buy our first house. That’s because Mother didn’t see what Father saw. We would have a street number to ourselves, 368.

The first days at 368, Mom refused to eat in the kitchen, and how could she eat in there? How could her children eat in that thing Dad called kitchen? Yes, the house included a small stove, but cockroaches were baking their own feasts in the oven. Dad imagined a swing set for Crucito in the backyard’s green lawn. But Mother had heard the neighbors walking by say the backyard turned into a swamp during the rainy seasons. Dad imagined a one-foot swallow lined with miniature plants that would keep the water moving to the large apartment complex next door. But Mom saw the swamp at our feet. Dad imagined the pantry and mom’s new wooden cupboards. But Mom saw mice and cockroaches. Lots of cockroaches. Mom saw the faded dilapidated and peeling mint green paint. Dad saw a new wooden exterior and a fresh coat of paint.

Our new but old kitchen was infested with silky brown cockroaches—the thin kind that matched the plywood. Underneath the crawl space lived the critters, and at night, big roaches squeezed and welcomed themselves in through both the front and back door to drink water and eat crumbs. Paloma and I, in our superhero capes, made from black trash bags, became Las Cucaracha Warriors de la Noche and ran after the cucaracha bandits. We routinely turned off the lights, and then at about ten o’clockish, Mom turned on the kitchen lights, and Paloma and I charged at them. While they scattered everywhere, we all took our turns killing the horde of nightly visitors. The pest problem at 368 went away with endless nights of Raid attacks and hot water splashing. Paloma and I even conquered our cockroach phobia and squished cockroaches with our very own index fingers.

The master bedroom had seven layers of dusty carpets pancaked on top of each other. The wooden floor in our living room held itself together miraculously—we were always careful to wear shoes to prevent any splinters from pricking our bare feet.

When we finally settled into our new home, one Saturday morning Paloma and I still in our pajamas were arguing over who would have to sweep and mop before our parents got home from work when suddenly we found ourselves shoving and wrestling each other. And then with a big push, the unexpected happened. I flew through the wall.

“Oh my God, Chofi! Look what you did!”

“Look what I did? You pushed me, Mensa!”

Paloma and I had to reconcile immediately to cover up the crime scene.

When Dad got home later that afternoon and walked through the hallway to inspect our chores, he demanded an explanation, “¿Y este pinche sofá? ¿Qué está haciendo aquí?” Chanfles, we thought as our eyes placed the blame on each other. Dad gave us the mean Martinez Castillo stare with the white of his eyes showing that always worked, shook his head, and stormed out of the house because Dad knew he had to replace all the house’s old plywood with new drywall.

Our idea of placing a love seat in front of the hole to cover it up didn’t work. Our fear for our father’s punishment turned into giggles and then uncontrollable laughter. Poking at each other’s ribs and yelling at each other, “It’s your fault!” and “No, it’s your fault!” we almost peed our underwear. We laughed at the hole in the wall, the sofa that barely fit in the hallway that must have looked ridiculously out of place in our father’s eyes, and at our new but old house facing the boulevard.

Strangers driving by honked or waved and gave Dad a thumbs up when he worked on our house on the weekends. We were living in Father’s dream home, and we were happy. José Armando, our real estate agent, was right—Dad fixed our house, and Mother created her garden of dreams, where Dad and Mom planted hierbas santas. Orange, avocado, peach, cherimoya, guava, and purple fig trees. And native yellow-orange, deep-purple, and rose-colored milkweeds for our butterfly relatives who passed by and travelled south to Michoacán, our parents’ homeland. One day we would follow them if Mom and Dad worked hard and saved enough money. One day.

In San Marcos, our backyard smelled like Idaho. The familiar smell of manure from the Hollandia Dairy on Mission Avenue lingered in our backyard. Months before the guava tree joined us at San Marcos Boulevard, Mom took free manure from the dairy for our garden and prepared the earth with water. Even if we already had a few trees, Dad and Mom talked about the trees and plants with special powers that would join our family. Next to the guayaba tree’s new home, the apricot tree had already joined us, and now it was the guava tree’s turn to step out of its black plastic container and to spread its roots and branches. At the end of the week with their Friday paycheck, Mom and Dad’s eyes were set on an árbol de guayaba.

Right after work Dad drove us to the northside of San Marcos on the winding road to Los Arboleros, the tree growers’ ranch on East Twin Oaks Valley Road, to buy the perfect tree for our backyard. As we approached a dirt road leading to the Santiago property, Don José in his sombrero and red and yellow Mexican bandana tied around his neck waved at us. At his side, two large Mexican wolfdogs with imposing orange eyes barked at us as we approached the nursery next to their house.

“Paloma and Chofi, be careful with Don Jose’s dogs.”

“Okay Ma,” we answered in unison.

“Buenas tardes, Francisco and Helena. Don’t worry, Señora Helena. My calupohs don’t bite unless they smell evil. They scare off the coyotes that want to get into the chicken coop. Last week a red-shouldered hawk snatched one of my María’s chickens in broad daylight.” Don José’s dogs, Yolotl and Yolotzin, sniffed our stiff bodies while I prayed to San Jorge Bendito: “San Jorge Bendito, amarra tus animalitos . . . .” Yolonzin sniffed and licked my hand. Thankfully, Don José’s calupohs remembered us; we were in the clear. “If you need anything, holler at me. I’m going to water the foxtail palm trees on the other side.”

At Don José and Doña María de la Luz Santiago’s small ranch, Paloma and I were careful not to step on rattlesnakes. We walked through the rows of small trees in 15″ containers and played with sticks next to a large flat boulder with smooth holes. I filled the holes with dead leaves and dirt and mixed it with a stick. “Paloma, let’s ask Don Jose about the holes on this large boulder. How do you think these holes got here?” Paloma shrugged her shoulders and signaled with her head to get back. With the calupohs following us, we found Mom and Dad still deciding on a tree and a crimson red climbing rose bush.

“But Pancho, look how green the leaves look on this one!”

“Yes, Helena, but look at this one. It has a strong tree trunk.”

“Pancho, this one has ripe fruit! Smell it, Pancho. With time, this one will be strong too.”

“You’re right, Helena. We can take the one you want. Let’s pay Don Jose and get going before it gets too dark, so we can plant our tree today.”

“Yes, Pancho, it’s a full moon!”

“Paloma and Chofi, I’m glad you’re both back. Go look for Don Jose, and tell him we’re ready to pay.”

Paloma and I ran to look for Don José. On our way to find him, I remembered we needed to ask him about the holes on the boulder.

“Hola Don Jose. My mom and dad are ready to pay.”

“Let’s go then.”

“Don Jose, we have a question for you. We saw a big flat rock on your property, and we’re wondering how the holes got there.”

Don José cleaned his sweat with his bandana and gave us a pensive look.

“Those holes. Well, Chofi, as you may know, this land you see here from Oceanside all the way to Palomar Mountain and beyond was inhabited by Native people. Women sat and pounded acorns on metates like the one you saw and made soup and other foods. You can only imagine how many years it took for those indentations to leave their mark and to withstand time. Those women, Chofi and Paloma, left their mark.”

“Oh, wow, Don Jose. That’s why the road is called Twin Oaks Valley Road? It’s a reference to Native people’s trees, who lived in this area?”

“Yes, Chofi and Paloma. Native people still live on these lands—in Escondido, San Marcos, Valley Center, Fallbrook, Pala, and Pauma Valley and beyond. Ask your U.S. history teacher about the people who inhabited these lands. I’m sure they can tell you more.”

“Thank you, Don Jose. I’ll ask.”

Dad and Mom paid Don José, and off we went to plant our guayaba tree. With our guava tree sticking out of the window in the Monte Carlo and lying on Paloma, Crucito, and me in the back seat, Mom was all smiles and kept glancing back.

“Pancho, please drive slowly and turn on your emergency lights. Children, hold onto our tree carefully.”

“Don’t worry Helena. Two more stop lights, and we’re almost home.”

Dad agreed to Mom’s pick because he knew she loved guayabas—all kinds. This time they chose the one with the two guayabas with pink insides, which wasn’t too sweet and just about my height. I preferred the bigger trees at Los Arboleros. Why couldn’t we get bigger trees? Mom and Dad always chose the smaller trees because those were the ones we could afford, and plus we didn’t have a truck like our neighbor Don Cipriano’s, but maybe we could borrow it next time.

As soon as we arrived home, Dad cut the container down the middle with a switchblade, and Mom pushed the shovel down with her right foot and split the earth.

“¡Ay, ay! ¡Ay Pancho! Be careful with the tree’s roots. Here, grab the shovel. Let me hold onto the arbolito.”

Dad dug the hole, exposing the dark brown of the earth as two pink worms shied away from the light.

“Dad, can Crucito and me get the worms, pleaseee?”

“Hurry up Chofi and Cruz. Go ahead. Your mom and I want to plant the tree today.”

“Okay, Apá!”

While I carefully took the worms from their home, Mom held the guava tree as if she held a wounded soldier and whispered to the tree, “Arbolito, don’t worry. You’re going to be safe here. I’m going to water you when you get thirsty and take care of you—we all will.”

“Pancho, one day we’re going to make agua de guayaba.”

“Sí, Helena, we’re going to make guayabate like the one my mom used to make. It was so good!”

“I bet it was, Pancho. To prevent a bad cough, my mom used to give us guava tea to fight off the flu.”

“Helena, did you know guava leaves are also good for hangovers?”

“Ay Pancho. ¿Qué cosas dices? Let’s get this tree planted.”

From the dried-up manure pile, Dad mixed the native soil and compost and pulled the weeds. As Mom placed the rootball above the hole, they both looked for the guava tree’s face and centered the tree on top of the hole. With the shovel, Dad poured the dirt around the tree. Mom took the shovel from Dad and pounded softly on the dirt surrounding the guava tree, making sure they left the edge below the surface.

Next to the apricot tree with a woody surface, the small guava tree with tough dark green leaves would be heavy with fruit one day for our family, our neighbors, and friends. Dad went looking for a canopy for the young guava tree to protect her from winter’s threatening frostbite, and mom stood in the garden, admiring our new family member.

It was time to return the worms to the earth; they were so tender but so strong. I made a little hole with my hand, placed the worms inside, said thank you to the worms, and covered them with dirt. The guayaba tree would make a perfect home.

Archives

April 2024

March 2024

November 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

December 2021

November 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

December 2020

September 2020

July 2020

November 2019

September 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

February 2010

Categories

All

Archive

Aztec

Aztlan

Barrio

Bilingualism

Borderlands

Boricua / Puerto Rican

Brujas

California

Chicanismo

Chicano/a/x

ChupaCabra

Colombian

Colonialism

Contest

Contest Winners

Crime

Cuba

Cuban American

Cuento

Cultura

Culture

Curanderismo

Death

Detective Novel

Día De Muertos

Dominican

Ebooks

El Salvador

Español

Español & English

Excerpt

Extra Fiction

Extra Fiction Contest

Fable

Family

Fantasy

Farmworkers

Fiction

First Publication

Flash Fiction

Genre

Guatemalan American

Hispano

Historical Fiction

History

Horror

Human Rights

Humor

Immigration

Indigenous

Inglespañol

Joaquin Murrieta

La Frontera

La Llorona

Latino Scifi

Los Angeles

Magical Realism

Mature

Mexican American

Mexico

Migration

Music

Mystery

Mythology

New Mexico

New Mexico History

Nicaraguan American

Novel

Novel In Progress

Novella

Penitentes

Peruvian American

Pets

Puerto Rico

Racism

Religion

Review

Romance

Romantico

Scifi

Sci Fi

Serial

Short Story

Southwest

Tainofuturism

Texas

Tommy Villalobos

Trauma

Women

Writing

Young Writers

Zoot Suits

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed