Mrs. Reed’s Christmas Treeby José Antonio López In addition to sharing our early Texas history with others through my Rio Grande Guardian online newspaper articles, I also wrote about growing up in El Barrio Azteca in Laredo, TX, such as the example below, first published on December 24, 2013. It describes the time when I first learned of the special Gift of Giving during the Christmas season, and whose message still applies today. Wishing you and yours a very Merry Christmas (Feliz Navidad) 2022. For most people, childhood Christmas memories serve as imaginary gold nuggets treasured for a lifetime. One of these gems is also my earliest recollection of when I first learned the true meaning of Christmas giving. It was 1953; I was about nine years old and in Third Grade at Central School in Laredo, Texas. Mrs. Reed was my teacher. Authoritative, yet warm and friendly, Mrs. Reed was a classic elementary school teacher. Effective and practical in her no-nonsense approach to teaching, she constantly challenged us to learn. In her classroom, “Eyes and ears on the teacher” was the rule. A few days before the Christmas holidays vacation, she would purchase a small Christmas tree and placed it in the middle of one of the classroom work tables. She also bought the tinsel and garland. Then, each student in class was asked to donate one ornament. They could either make it in class or bring one from home. Trimming the tree was an extra treat for us students. As a reward for good behavior, she allowed us to help her adorn the tree, which was done a little each day. By the time we had our class Christmas Party on the last day of school, the tree was finished. Not all teachers went the extra mile. So, after lunch on that special Friday, teachers formed a line outside our classroom and brought their students to view and admire our creation. Barrio El Azteca was mostly poor blue-collar. Most of our neighbors were hard-working day-labor folks and migrants. They arose before day-break and returned home at nightfall; dead tired after their day at a building site in town or working at one of the area’s ranches and farms. The next day, they did it all over again. Their pay was dismal; and employment for day laborers was erratic. Knowing that Christmas trees were a luxury in some children’s homes, Mrs. Reed responded with her own style of kindness. During the last day of school, she put all our names in a bag. She then asked a fellow teacher to pick a name from the bag. The student whose name was drawn won the Christmas tree. More than anything that particular Christmas, I prayed that I would be the lucky winner. Having overheard my parents a few days earlier, I knew money was tight in our monthly budget. It seemed that they might not be able to buy a Christmas tree for us that year. That’s not to say that our house wouldn’t be decorated for the season. Mother always did a great job decorating our home with very limited resources. Too, the center point inside the house was a small Nativity set in the living room. Yet, the spot reserved for the tree was empty. So, it was with great anticipation that I welcomed the last day of school before our Christmas break. The Christmas Party was well underway that afternoon, when all of a sudden, I heard my name called. I couldn’t believe it. I had won the prize. When the dismissal bell rang, I asked Bernardo, a classmate, to assist me in carrying it home. He agreed. Mrs. Reed helped us remove some of the breakable ornaments and she put them in a small box. As soon as we reached the outside of the school building, every step of the way became difficult. First, we had to maneuver a steep stairway in front of the school entry. In one arm, Bernardo carried our notebooks and in the other, the small box with the ornaments. I carried the tree still sporting the tinsel and garland. Second, balancing the tree upright in front of me, my view was very limited. Walking on the unpaved, gravel, street was tricky. So I walked on level ground, avoiding any large rocks that might make me fall. A slight wind was blowing and small bits of tinsel were dropping off the tree, marking our way. We were a sight to behold! Our house was about six blocks from Central School. Bernardo’s house was half-way to mine. So, before we knew it, we had already walked the three blocks to his home. I placed the tree on the ground and waited for him to drop off his school books and tell his mom he was helping me get home. After a moment, his mother walked out to admire the tree and went back inside. It was then that I realized Bernardo’s home didn’t have a Christmas tree. Suddenly, a hard-to-explain powerful feeling overcame me. I asked Bernardo to open his front door. Before he had a chance to ask why, I carried the tree inside and placed it by the front window. Hearing the commotion, his mother walked out of the kitchen and I asked her if she would like to keep the tree. She was stunned, and began to weep. She gave me a big hug, nodded “yes”, and thanked me. Then, I helped Bernardo put the ornaments back on the tree. It immediately brightened up the room. As I left, the two of them were quietly standing admiring their beautiful Christmas tree. When I got home, other kids had told my mother of my winning Mrs. Reed’s Christmas tree. As soon as I entered our home, Mother asked me where it was. When I told her what had happened on my way home, she began to cry just like Bernardo’s mom. Mother gave me my second big hug of the day. She then called Dad at work and told him what I had done. My father, a stern man of few words, but possessing a big heart himself, approved of my charity. That evening, he returned from work with a Christmas tree strapped to the top of his car. In summary, I tell this story to focus on the plight of today’s needy. Having lived the experience, I am in a position to say that poor people don’t enjoy being poor. Nor are they lazy. That is why they don’t deserve the unkind treatment they receive almost daily from politicians and some news commentators. The fact is the poor are in a never-ending struggle to improve their quality of life. They only ask for a compassionate helping hand to grab onto the next rung in the ladder of success. This Christmas let’s all be part of the solution by helping them do it.  José “Joe” Antonio López was born and raised in Laredo, Texas, and is a US Air Force veteran. He now lives in Universal City, Texas. Joe is the author of several books. His latest is Preserving Early Texas History (Essays of an Eighth-Generation South Texan), Volume 2. Lopez is also the founder of the Tejano Learning Center, LLC, and www.tejanosunidos.org, a website dedicated to Spanish Mexican people and events in U.S. history that are mostly overlooked in mainstream history books.

0 Comments

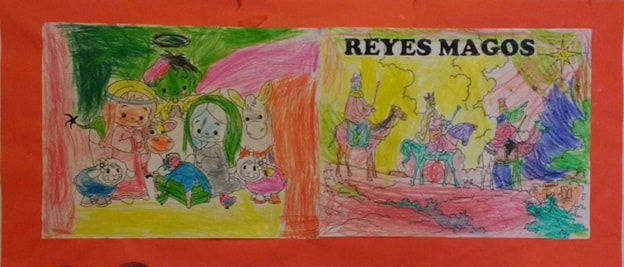

THE THREE KINGS RIDE ON DESPITE GLOBALIZATIONDESPITE GLOBALIZATION By Álvaro Ramirez 18 JANUARY, 2019 Many Mexicans who grew up in the sixties and seventies remember when Las Ardillitas (Alvin and The Chipmunks) used to sing Christmas songs in Spanish and Pánfilo, the bad ardillita, was always making funny comments that undermined the Christmas message of the songs. The manager, Lalo Guerrero, considered his comments improper and admonished him: “I’m absolutely certain that Santa Claus will not bring you anything.” To which Pánfilo responded: “Who cares, I’m not a client of that man; the Three Kings bring me my toys.” Back then, many people sympathized with Pánfilo and saw Santa Claus as an exotic American foreigner, nowadays it seems that sentiment has gone by the wayside, but is this really the case? Any way you look at it, the Mexican holiday season has taken an American turn, especially during the NAFTA epoch, every year we can see the spirit of an American Christmas gaining ground in Mexico and giving the old Mexican yuletide traditions a run for their money.  Photo: Álvaro Ramírerz Photo: Álvaro Ramírerz You can find Christmas trees (fake and not too attractive) in most downtown areas of big cities, surrounded lately by an ice rink in an attempt to recreate the festive ambiance of cities like New York. Colorful lights and decorations, made easily available through COSTCO and Walmart hang uneasily from roofs, walls, and around windows or adorn artificial trees in many homes. Walk through any Galerías Mall or Supermarket and you can merrily shop along isles trimmed with wreaths, mistletoe, silver bells, and Christmas carols (sung in English) swirling all around, seducing you to shop for the perfect gift for your loved ones. Television programs and movies like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer also stir up the holiday cheer, American style. And of course, you will find a Mexican Santa Claus somewhere in a Plaza Galerías ready to take a picture with you so you can post it on your Instagram and Facebook and relieve the memory forever. Yet, far away from downtown areas, malls, and transnational stores, in the barrios one can still hear the beautiful sounds of Las Posadas with their ancient Spanish Christmas songs, piñatas, aguinaldos (gifts of candies), and great food. Christmas Eve (La Noche Buena sounds better, the words strike a beautiful chord within us) still brings the family together to share a special meal of tamales and other traditional foods. Many people attend the midnight church mass to witness the birth of Baby Jesus (almost always a little too white, but who cares) to Mary and Joseph in a manger surrounded by shepherds, sheep, an ox, and a mule; overlooking it all a beautiful angel. It is a ritual that reinforces the bonds of family and community. Even more far away, over in the Orient Three Magic Kings, Melchor, Gaspar, and Baltazar, get ready to do battle with the laughing, merry, old Nordic Man. In the days before Santa Claus invaded their territory, the kings began their trip around the world early to arrive and deliver gifts in every home during the magical morning hours of January 6. Throughout the previous afternoon and night, radio disc jockeys announced their regal whereabouts: a plane spotted The Three Kings over the Pacific Ocean; they have just passed the islands of Hawaii, soon they’ll arrive at the Baja California Coast. Go to sleep children and leave hay for the camels that the Three Wise Men are riding laden with gifts, which they’ll stuff into millions of shoes. The excitement of the anticipation made it difficult for children to restfully sleep on this enchanting night. Nowadays, the situation is a little tough for these wise men from the Orient. Santa Claus is a hard act to follow but the Three Kings still have their magic. In the old days, children used to imagine them loading up somewhere in the Orient even though it was popularly thought that Melchor was Spanish, Gaspar an Arab, and Balthazar an African (religious authorities saw them as learned men; Melchor as king of Persia, Balthazar king of Arabia, and Gaspar king of India). The star they now follow takes them through the Far East and they make a stop in China. That’s where they pick up the toys probably put together by underpaid Chinese children for Mexican children. The toys may have a little too much lead content, but who cares, they’re cheap, and this is all the Three Kings can afford to deliver to many households in Mexico. The same toys you can find being sold on the sidewalks surrounding town centers and public markets, teeming with people on January 5th. These are the gifts that will find their way into many shoes throughout Mexico, with the help of the Three Wise Men, to bring happiness to millions of children. Yes, Pánfilo, despite the fact that globalization helps Santa Claus gain followers by leaps and bounds, there are still many Mexicans like you who are faithful clients of The Three Kings. These Mexicans are not as separated as it might seem, some may look toward the mall and others toward the sidewalk and public market vendors to celebrate the birth of Jesus, still they are united by the magic of the magi when both groups buy the yummy rosca de reyes (a sort of oversized pastry donut or bagel) to share with family. In this way, the Three Kings bring together Mexicans on January 6, as they gather round “la rosca” to break bread literarily and figuratively as a nation. It does not end there; inside those oversized donuts are several, tiny plastic Baby Jesus. If you get one in your slice you are obliged to continue the harmony brought by the Magi. You will gather everyone again on February 2, Día de la Candelaría (Candlemas), to eat tasty tamales, paid by you. In spite of globalization and the expansion of Santa’s influence, the visitors from the Orient are still quite relevant in our lives: The Three Magic Kings still rule! A different version of this postcard was previously published under the title, “I grew up believing in the Three Wise Men. I think they are way better than Santa,” that appeared in Cultura Colectiva, a Mexican digital magazine in January 2019.  Álvaro Ramírez is from Michoacán, México. He migrated with his family to Ohio as an adolescent. He obtained a BA in Spanish and Education at Youngtown State University, and an MA and PhD in Literature from the University of Southern California. He has taught at various institutions including the University of Southern California, Occidental College, and California State University, Long Beach. Since 1993, he has worked at Saint Mary’s College of California where he is a Professor in the Department of World Languages and Cultures. He specializes in Spanish Golden Age and Latin American literature as well as Mexican Film and Chicano Cultural Studies. He recently published the book, Postcards from a PostMexican on the swiftly evolving transnationalization of both cultural and political characters of the U.S. and Mexico. How the Holiday Season is Changing the National Identities of Mexico and the U.S. If you have traveled abroad lately, you may have noticed that national identities are becoming a bit vague. The cultural uniqueness that used to distinguish one nation from another has been quickly disappearing thanks to the accelerated pace of cultural contact brought about by globalization. Mexico and the USA illustrate this well as we go through the holiday season. Millions of Mexican immigrants, legal and undocumented, as well as tourism between both countries have created cultural contact zones unlike any in human history. As they have settled in these areas of the United States, Mexicans have adopted American habits even as they have maintained much of the cultural heritage they brought with them. For example, they love Thanksgiving turkey and on Black Friday you can find them shopping like crazy across the malls alongside Americans. December, however, is a Mexican fiesta north of the border. Los americanos are growing accustomed to seeing and joining the solemn Virgen de Guadalupe celebrations around December 12th and breaking piñatas in the noisy, colorful Posadas on December 15th-24th. Moreover, Mexicans have fused seamlessly La Noche Buena (Christmas Eve) and Christmas Day, so they can have their tasty tamaladas and receive the birth of Jesus with tons of gifts the good old American way. As many Mexican immigrants return to visit family in Mexico, they bring along these new cultural customs, especially their sons and daughters who were born and raised in the United States. You can see the influence of these new cultural ways in small towns and cities across the country. Mexicans now have their Buen Fin, a clone of Black Friday, and on Thanksgiving more and more people are preparing a turkey dinner a la americana or go to restaurants that offer a similar menu. As for Santa Claus, Christmas trees and carols, they are the norm everywhere. It may seem strange, but in Mexico City and Cuernavaca, you can even go ice-skating downtown! You could say Cinco de Mayo was the first cultural celebration to bring Americans and Mexicans together, and that lately Día de los Muertos and Halloween have provided more cultural glue that binds people on both side of the border. But it is the long holyday season at the end of the year that is having the biggest impact on our identities and how we see ourselves in Mexico and the United States. Mexicans who visit the U.S. and Americans who travel to Mexico are bewildered by this turn of events. National identities may still be around, but the unique cultural elements that separated them are blending fast and, in some cases, disappearing and becoming a thing of the past.  Somos en escrito Literary Foundation Press published a compilation of Álvaro Ramírez’s observations on changing cultural traditions: Postcards from a PostMexican. Click the cover above or visit Amazon to buy a copy. This postcard first appeared on Álvaro Ramírez’s Postcards from a PostMexican blog on December 24, 2019. This postcard was published under the title “How the Holiday Season is Changing Mexican and American Cultural Identities” in Cultura Colectiva, a Mexican online magazine, on January 2, 2020.  Álvaro Ramírez is from Michoacán, México. He migrated with his family to Ohio as an adolescent. He obtained a BA in Spanish and Education at Youngtown State University, and an MA and PhD in Literature from the University of Southern California. He has taught at various institutions including the University of Southern California, Occidental College, and California State University, Long Beach. Since 1993, he has worked at Saint Mary’s College of California where he is a Professor in the Department of World Languages and Cultures. He specializes in Spanish Golden Age and Latin American literature as well as Mexican Film and Chicano Cultural Studies. He also serves as Resident Director for the Saint Mary’s College Semester Program in Cuernavaca, México. In 2016, Prof. Ramírez published a collection of short stories, Los norteados, which received an Honorable Mention Award at the 2017 International Latino Book Awards. In addition, he has edited two online publications of Conference Proceedings: Imágenes de postlatinoamérica, volumen 1 (2018) and Imágenes de postlatinoamérica, volumen 2 (2019). He has also published articles on Don Quixote, Mexican film, and Chicano Studies in several academic journals. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed