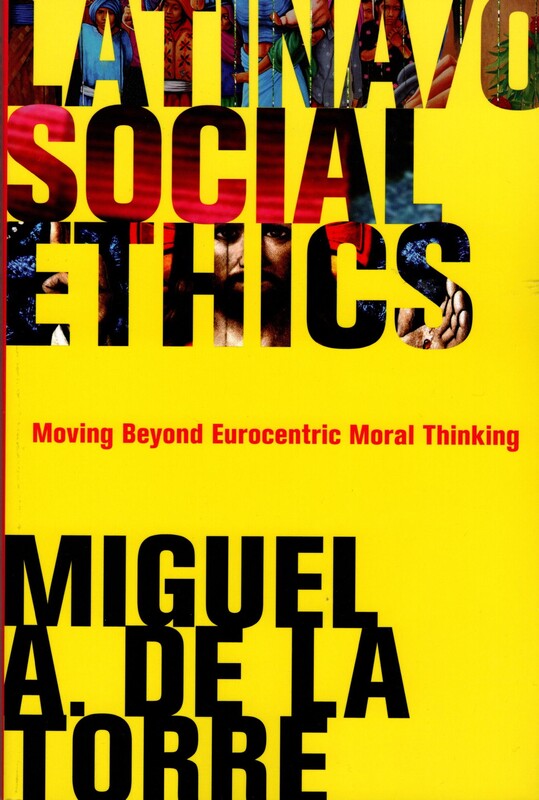

"We have been taught to see and interpret reality through the eyes of the dominant culture"10/26/2022 An excerpt from Latina/o Social Ethics |

A Social Media Post:

On Being Asian Latino

(Or, On Becoming Gringo)

By Moisés Park Today. I was both an alien y un gringo.

Hoy fue mi último día como alien en EE.UU. Desde las 10 de esta mañana soy ciudadano de este país. Por 18 años fui residente en Chile (y Bolivia y Brasil) con dos pasaportes verdes (coreano y brasileño) pero para simplificar las cosas siempre usé el coreano. Y claro... he pasado un total de 42 días en Corea en cuatro viajes separados y me encanta la música pop de Corea de los 80 y 90. #kpoptodaysucks #kpopdehoyesunamierda

Han pasado 18 años desde que vine a EE.UU. a estudiar como estudiante extranjero. Pero siempre había sido extranjero en Chile. En Patronato donde me decían “chino cochino” por las calles o si yo era (primo/hermano/hijo/nieto/clon de) Bruce Lee. Y en Corea nunca me sentí “en casa”. Será que como mis cuatro abuelos son del Norte (antes de la división) soy más del campo que de la ciudad y nunca conocí de verdad el campo coreano.

at a conference in New York City

tomorrow, February 22, on

“Intersections: Between Asia

and Latin America" sponsored

by the Graduate Center, CUNY

Nunca pertenecí a ningún lado. Cuando vuelvo a Patronato, el barrio palestino-coreano-cada-vez-más-chino en Santiago, me siento turista, pero quizás siempre lo fui. De hecho, no sé por qué estoy escribiendo esto en castellano cuando la mayoría de mis amistades ahora no hablan castellano. Castellano = español. Es que a veces todavía digo castellano en vez de español. #itsachileanthing #alsoinspain #alsoinargentina

I became a citizen today and when I write this part in English, which I am not translating, I feel very different. My life in the US has been so different from the one in Chile. (I remember nothing from Bolivia and Brazil. I was a newborn). I had two coming of ages and maybe I am still a teenager figuring out what I am.

I remember wise words from pastor Flores Park, our youth pastor then, who told us to embrace our Chilean identity and Korean identity fully. #lotsinkoreandiasporaattendevangelicalchurches #manycomeforthefreefood She said that it's OK not to belong fully but to somehow love both of my heritages and consider myself 100% Chilean and 100% Korean. Or that it is fine to identify with a third identity: to be a Korean-Chilean who loves jote (Coke+wine) and empanada but still eats kimchi every single day. #shedidntsaythejotepart

But I've been in the US for 18 years now, since I was 18 years old. #crossroad #encrucijada. I am Asian Latino or whatever sociologists and other social scientists say I am or should be called. chinkleno? #notpcenough #toospanglishy

Asian? Latino? Asian Latino? Asian Latin American? Asian American Latino? Asian Latinx? Latin American Asian? Latin Asian? Latinx Asian? Lasian? Latinaxian? Laxian? Laxatixasiax? Korsian? ChicKorea? Chil-Korean? Chilax-Korean? Ko-chi-merican? #whynotjustperson #aw #weallarepeopleafterall #aw #isthatcolorblindness #kochimerican

I am a Korean heritage speaker but I cannot type these thoughts in Korean. I mean I could try, but my mom would go crazy with the editing. (My mom often sends me spelling corrections when I text her.) 그건, 임뽀시블레 (That’s impossible).

I share what many Latinos and Asian Americans feel when they have to express themselves in their “mother tongue” or “heart language.” A feeling of linguistic humility (closer to a feeling of timid shame) for not “keeping” the language at the same level as Spanish or English, the dominant languages. Plus, my Korean is so mixed with Spanish (English now) that my Korean is often full of vocab, spelling and grammar “mistakes.” It's Konglish or Coñol. But Coñol sounds like a bad word in Spain. Coreañol? #buthisainspain #coñol

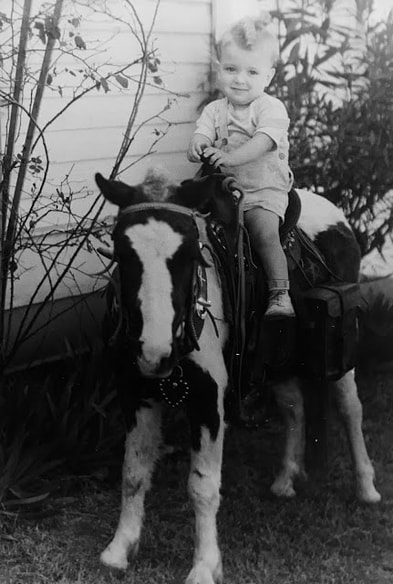

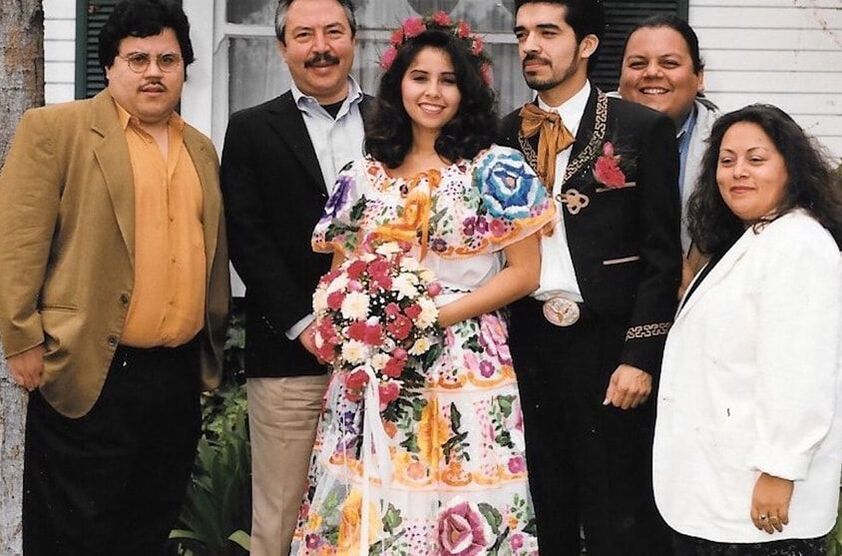

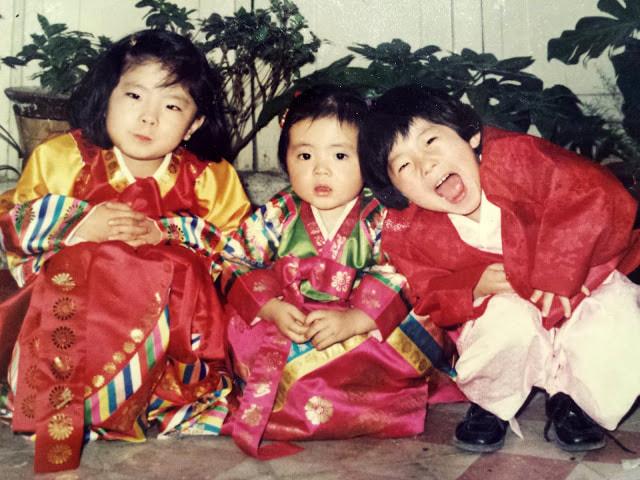

El cumpleaños de su papa, Ki-Chul Park, 30, con su mama, Hae-Soon Kim, 30, y Moisés, 3, circa 1985.

El cumpleaños de su papa, Ki-Chul Park, 30, con su mama, Hae-Soon Kim, 30, y Moisés, 3, circa 1985. Videos today at the oath ceremony featured Mt. Rushmore and Lincoln, lots of eagles and American flags, and lots of diverse faces smiling, and eagles, and the Golden Gate and eagles, and American flags. It looked like a car dealer commercial but with eagles and diverse faces smiling. That friend that gave me different versions of American pride once said Jimi Hendrix protesting the war while emulating bombs with his guitar was perhaps one of the most patriotic performances.

I was waiting for the video to show images of Jimi Hendrix, and Rosa Parks and MLK, Jr., who was killed 50 years ago today. And Richard Twiss. And James Baldwin. And César Chavez. And Carlos Bulosan. And Billie Holiday. And Marilyn Monroe. But it's OK. There are contradictions in every country and maybe, I am suffering from false nostalgia and pretentious wokeness.

#iswokenessaword #millenialwannabeusinghashtags #iamtheoldestmillenial #notkidding #iturned18inyear2000

Siempre sufrí de un falso orgullo por Chile, por Bolivia, por Brasil. Como que sentía que no pertenecía, que no me dejaban pertenecer, o que es imposible pertenecer, o que era eternamente coreano. Pero cuando Chile destruyó a México el año pasado 7-0 (y cómo xuxa no están en el mundial!), celebré como chileno (porque soy/era/fui chileno?), con gritos de gol que duraban mucho y muchos “chucha!” (damn!) y “la cagó!” (OMG!) y “el Puch tiene buen pique” entre amigos y familiares también coreano-chilenos, pero que de coreano solo tenían hábitos culinarios y memorias o planes de viajes en Corea.

Es cierto, siempre fui “chino cochino” en Chile por más que gritara un chichichilelelé (National chant, mostly chanted in sports events) o fuera hincha del Colo-Colo (by far, the best Chilean soccer team). Pero ahora soy gringo? #copamundial #sicopaesfemeninoentoncesdeberiaserLAmundial #castellanochilensis #lamicrodeberiaserelmicro #microbusenchileeslamicro #daigual

No sé. Tal vez soy más Isabel Allende que García Márquez. El libro Mi país inventadode Allende lo terminé de una. Lo encontré muy muy muy bueno aunque todos los nerdos de la academia me pifian y se enojan. Pero han leído ese libro desde la perspectiva de un cochino (COreanoCHIleNO)? Eso de inventarse más y más el país en el que un@ se crió, entre más años se pasa fuera. No todo es realismo mágico. A veces es más fome (boring, or lame), aun en “plena dictadura.”

Viví en dictadura más o menos (mucho menos que más) pero no cachaba (understood) realmente lo que estaba pasando. #lospendexchinosnocachabamosqueonda Tal vez nunca fui chileno, porque ni tuve idea de quién era Pinochet por muchos años, ni por qué el Superman y el Sting salían en la tele hablándole a los chilenos. (Christopher Reeve (Superman (1978) and Superman II (1980)) and Sting were among many foreign stars who advocated for the end of Pinochet’s regime in 1988’s plebiscite political campaign). Pero tengo memorias de amigos que se enojaban cuando uno coreaba el “Chile, la alegría ya viene” (Jingle for the 1988 TV plebiscite campaign) y daban un chócale cuando decía que iba a votar por el Sí en el plebiscito que decidía si Chile continuaba con el gobierno militar o la democracia. #memoriasdel88

Tal vez soy más Mistral que Neruda, y me las doy de súper poeta (cuando al final también hay mucho plagio y arrogancia en lo que escribo) y sinceramente prefiero cantarle rondas a mis niñitas que pensar en “los versos más tristes esta noche.” Tal vez Chile será siempre mi amor contrariado. A veces quise a Chile y Chile a veces me quiso. Tal vez me invento que soy chileno para parecer más exótico. Carechino con acento de Alexis Sánchez. Un Psy que canta “Bolsa de mareo” (qué buen tema ese...).

You know what's weird? I am Asian Latino but my girls will not inherit my Latinoness (Latinness? Latin mojo?). We will try to go to Chile every year, but visiting every now and then won't do much to them. Nor will they understand their Latino heritage through annoying song repeats of my first Chilean love, Nicole (Denisse Lillian Laval Soza), quizás mi primer amor chileno, or the Beatlesque Los Tres, Café Tacvba and la Violeta Parra, Sexual Democracia. #namedroppingpart1 #myfirstgringalovewasshera#myfirstkoreanlovewastheonlykoreangirlinelementaryschool#inelementaryschoolboysfallinlovewithprettymucheverybody

Igual trato de ser chileno. Soy mejor cuando pretendo ser coreano. Es que cuando hablo coreano nadie me pregunta: “Oye, y cómo chucha sabí hablar coreano?” Igual escucho Radio Cooperativa y veo TVN online o Chilevision o CÑÑ y los partidos de Chile y el Festival de Viña. #lanataliavaldebenitoesseca

Es suficientemente chileno eso? O los chilenos de verdad sólo escuchan Violeta Parra, Quilapayún y Faith No More? Mis clases igual son copia de mi profe de secundaria, el célebre Rodolfo Franco, un montón de Neruda y más Neruda y el Neruda es ídolo. (Igual nos faltó leer más a Mistral, no creen? Muy depre?). Apoyo (a full!) todo lo que es chileno en mis clases y mis estudiantes igual se han memorizado “Todo cambia” de Julio Numhauser y “Gracias a la vida” de la Violeta. Y vieron Machuca, Historia de un oso (#superchriste) y están enamorad@s del Marko Zaror, el Beto Cuevas, la Camila Gallardo, la Camila Moreno, la Camila Vallejo, la Anita Tijoux, y/o la Nicole #namedroppingpart2. #quelendaslaschilenas #todaslascamilassonlendas

Y les traigo manjar y jote a mis estudiantes y a mis niñas. No po, jote no po. Sería mucho. Qué creen shiquillos (kiddos)? Soy chileno todavía? O soy Moses Brandon Parker ahora? Igual no me debato mucho si soy coreano o no porque la carechino no se me borra nunca. #phenotypedictatessomuch

Que le pongo colooooooooooooooor (Chilean slang that means = I’m overthinking). Ya. Me callo. Soy gringo ahora. Eso quería decir.

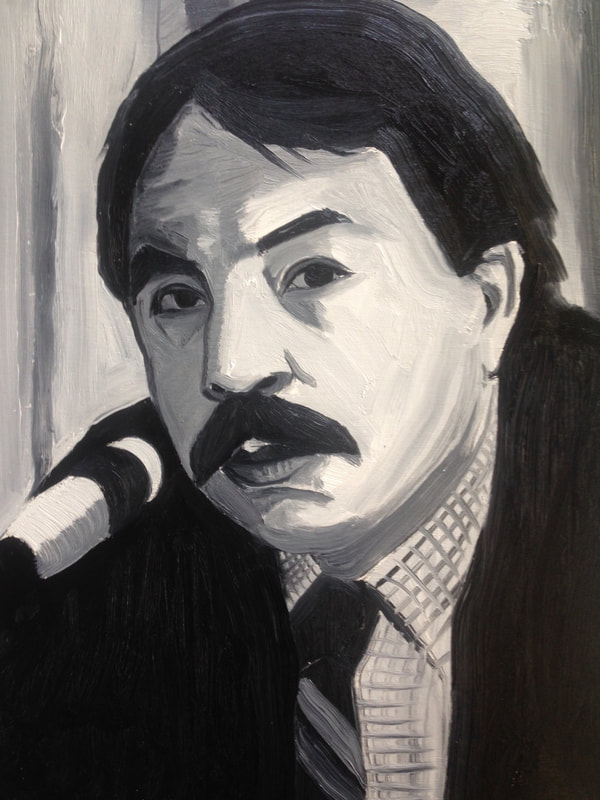

Lyndon Baines Johnson, then president, had ordered federal agencies to beat the sage bushes throughout the Southwest to recruit Chicanos and Chicanas to join the ranks of federal workers. I got a job at the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights as a press officer. Tocayo got a job running the HEW Office of Spanish Speaking American Affairs. Happily, our paths crossed many times during his several stints in the capital. He will always be a dear friend.

His obituary, which appeared in the Associate Press News, follows:

Armando M. Rodriguez, a Mexican immigrant and World War II veteran who served in the administrations of four U.S. presidents while pressing for civil rights and education reforms, has died.

Christy Rodriguez, his daughter, said Wednesday her father died Sunday at their San Diego home from complications of a stroke. He was 97. He had been ailing from a variety of illnesses in recent years, she said.

Born in Gomez Palacio, Mexico, Rodriguez came to San Diego with his family as a 6-year-old in 1927. But he was forced to return to Mexico after his father was deported during the mass deportations of the 1930s during the Great Depression. A young Rodriguez lived in Mexico for a year before the family could return.

“He barely spoke Spanish,” Christy Rodriguez said.

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, some of his Mexican immigrant friends fled to Mexico to avoid military service. Rodriguez, however, joined the U.S. Army. “It was not a difficult choice,” Rodriguez told the Voces Oral History Project at the University of Texas in August 2000.

Following the war, Rodriguez graduated from San Diego State University and worked as a teacher and joined the Mexican American civil rights movement after witnessing his fellow Latino veterans being denied house and facing discrimination.

He led Southern California’s Viva Kennedy campaign, the effort to increase Latino voter support for John F. Kennedy’s presidential run in 1960. Rodriguez founded a chapter of the veterans’ American GI Forum civil rights group in San Diego as a junior high school teacher.

President Lyndon Johnson appointed him chief of the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare’s Office of Spanish Speaking American Affairs. President Richard Nixon later named him assistant commissioner of education in the Office of Regional Office Coordination.

Rodriguez returned to California to become the first Latino president of East L.A. College. In 1978, President Jimmy Carter appointed him to serve on the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Rodriguez continued to serve on the commission under President Ronald Reagan until stepping down in 1983.

Later in life, Rodriguez continued to advocate for educational opportunities for Latinos. But Rodriguez told the Voces Oral History Project that he had always wished he had been able to do more.

“The legacy you leave is what you were worth while you were here,” Rodriguez said.

Russell Contreras is a member of The Associated Press’ race and ethnicity team.

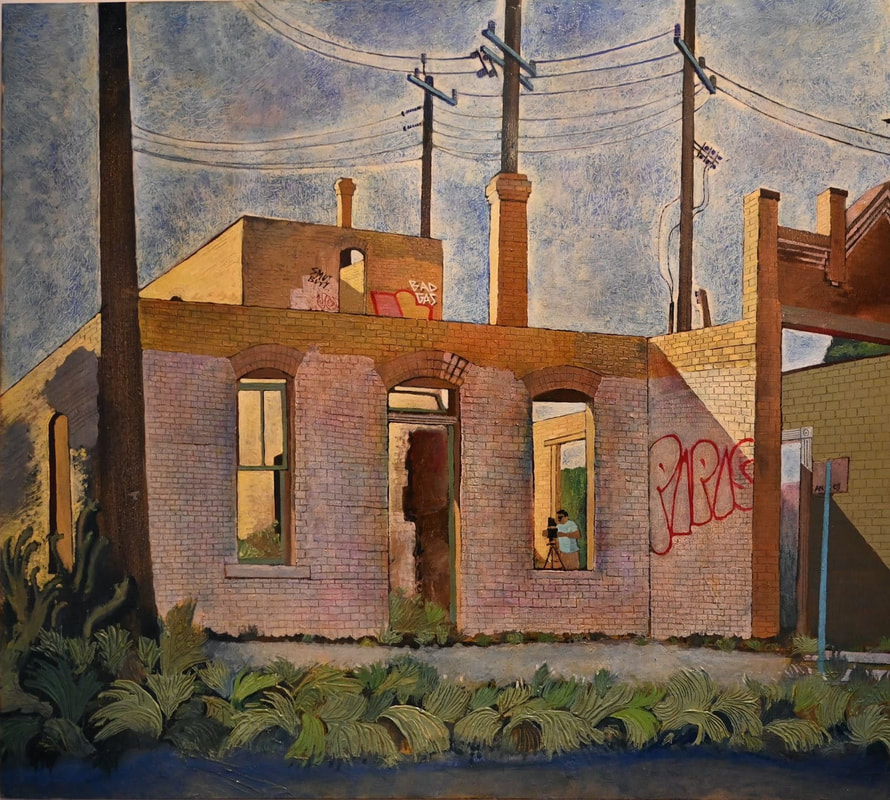

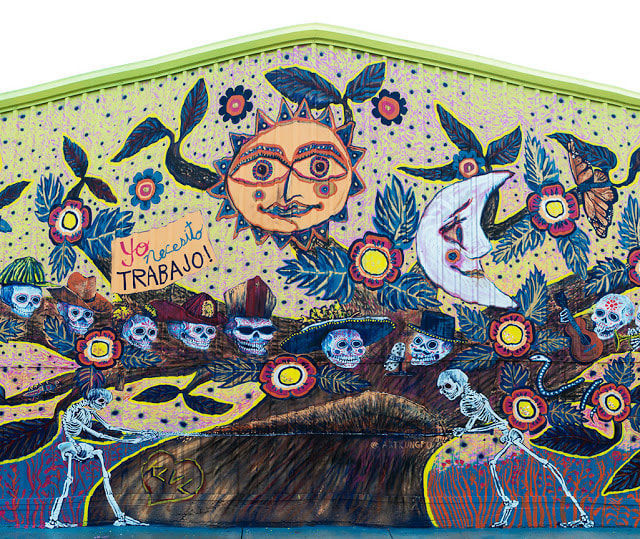

An Eye for

Community Art

We hope to learn more of Roberto deVillar's worlds in future columns.

--The Editor

Welcome to my worlds

First of all, let me introduce myself. By birth, I am a sinner, as are all Catholics, and a perennial outsider from the moment I burst forth from the internally secure universe of my mother’s womb. Transgressions and marginality; redemption and wholeness; wanting and sharing; hiding and seeking; standing firm and finding. These and other key elements constantly are in simultaneous play with one another throughout one’s life. And as we try constantly to wrestle with the elements to find ourselves, define ourselves, make sense of ourselves, justify ourselves, forgive ourselves, love ourselves, and the like, there are many times that we find ourselves pinned down by the elements.

I want to share aspects of my meandering journey toward working in the fields of social justice, and include the rocks and potholes that caused me to stumble, and the forks in the road that led to unexpected detours or dead-ends. At the same time, obstacles in my path never caused me to stop wandering in the direction that I thought was a forward one, fueled by the light of my passions, guided by the whispers, howling, and silences of my mind-soul’s inner voice. So I begin, claiming my birthright, to write as an outsider and confess.

I have always found my baptismal certificate from the San Fernando Cathedral in San Antonio, Texas, interesting. Along its left side, all the language is English. And all the names and even the month in which I was born are inserted to the right, handwritten in Spanish.

My name is listed as Roberto Alejandro DeVillar, which is the same name as on my original birth certificate; then Alfonso Arturo (my father), Cecilia (my mother—known as Nina), José Alejandro (my mother’s brother and my godparent, known as Nine), Guadalupe (my father’s sister and my godparent, known as Lupe), Rev. J. Frias (officiating priest), and my birth month is written as Junio. This integral blend of language and culture, literally from day one, was a birthmark, stamped on my soul, my character, my very being, and not only accompanied me to every geographical location, every cultural setting, and every social context in which I set foot, but influenced me, as well.

In my earliest days, although my parents and their siblings were what would be termed fully bilingual in Spanish and English, it was Spanish that was always spoken in the presence of my two remaining grandparents, who were Papá Bocho (Ambrosio Samudio Rodríguez), my grandfather on my mother’s side, who died when I was 7 years old; and, Mamá (Basilisa Riva Pellón), my grandmother on my father’s side, who lived for many years, passing away in 1976, at 94 years old.

The author at 1 year, nine months in San Antonio, Texas

The author at 1 year, nine months in San Antonio, Texas My Upbringing in Diverse Socialization and Cultural Contexts

The formal socialization contexts in San Antonio that I entered outside the home from pre-school to 3rd grade were Catholic. Here, nuns ruled with rulers in hand and—although this will be almost impossible to believe--strait-jackets, which both my older brother and I, on different occasions, were strapped into. I can still remember, not even being old enough to attend first grade yet, sitting down, crossed-legged, silent, as the strange, rough, canvas-like material was wrapped around my torso, locking me in by straps looped through shiny metal rings. I have neverforgotten that image or experience. It was far worse than when I was made to kneel to have my mouth washed out with soap by a nun for having uttered, I imagine, a swear word.

Then there was the snarling, wild-eyed anger projecting from my brother’s face as he sat, body pulsating, imprisoned in the strait-jacket, somehow still emoting strength and pride, even in that shocking, depressing condition. I was perhaps 4 years old, but that tortuous image of seeing my brother in the strait-jacket lives still within my memory and continues to haunt me.

And later, at Saint Ann’s, I vividly remember wearing with pride my khaki uniform with patches, tie and brass-buckled belt, raising my hand and waiting, without being acknowledged by the nun, until I finally summed up the courage to go up to her and asked her permission to go the bathroom. She responded: “No, it’s almost time for the bell.” I returned to my desk, and despite all the attempts a child does to stop his bladder from emptying, while sitting at my desk, I uncontrollably urinated, staining the front of my khaki pants down to the knee.

I waited for everyone to leave when the bell rang, but a girl stayed behind to wait for me, and I finally got up, saying in an utterly unconvincing tone that was supposed to be lightheartedly amusing: “Oh, Paul and I were playing at recess and he threw water on me!” She didn’t say anything, her look said it all.

I went outside to one of the side doors leading to the steps where the playground began, and wedged myself in a space between one of the recessed door frames and a low wall to become invisible. I then opened my tin lunchbox in such a way that its top extended across my waist, so that in case someone did see me, they could not see my urine-stained khaki pants. A nun came by, saw me, and asked why I was there, eating alone instead of being with the others on the playground. That was all it took for me to begin to wail and angrily tell her what happened.

Rather than comfort me, the nun began to defend the offending nun, and I, even at 6 or 7 years old, knew that was unjust. So, I hollered, still shedding tears of anger, that the offending nun was a Jackass! And, each time the nun would open her mouth to say something, I would repeat, again and again, “No, she is a jackass!” Until the nun finally realized that I was in a fit of rage, came to me, put her arm around me and guided me up the stairs.

The next thing I remember is that my mother was driving me home, saying that I would not have to return to school that day. And it was her calm, gentle, loving presence, even while driving, that enveloped me and made me feel warm and safe. That same summer, I asked my parents if I could change schools, and, even though my older brother stayed at St. Ann’s, I enrolled at St. Mary Magdalen’s.

Aside from being strapped in strait-jackets, having my mouth washed out with soap, and suffering the consequences of restricted bathroom use, it was also quickly transmitted within these various Catholic settings that we are all sinners and need to repent. Thus, Catholic school is also where I learned to confess.

The Why of Confession: Many Paths, One Goal

Confessions are, of course, two-sided. On the one hand, the confessor wishes to relieve the self of the weighty burden of guilt, of pain, of suffering, of mental torment, and so on, brought on by the internally conscious judgement that one’s action or actions have violated egregiously the moral rules, guidelines or expectations of a community in which membership is claimed.

On the other hand, the confessor takes this humiliating step, in which at least one other person is present, for the explicit sake of redemption, of being forgiven for one’s transgressions, however severe, and being reborn, so to speak, to go out and sin no more—which, as we all know, is an impossibility and the paradoxical bane of Catholics and other Christians.

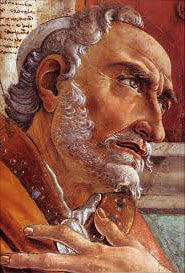

As sinners, we all inhabit two spaces simultaneously; that of the sinner—either actual or inevitably prospective—and the searcher who seeks forgiveness through confession for the sins committed and confession’s product, redemption. It is the same if one reads the eponymously titled autobiography, The Confessions of St. Augustine (circa 400 AD), or the tortured, tormented fictional tale of the murderous Raskolnikov, the young, feverish killer in Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866; spellings include Dostoyevsky/Dostoevsky). The opportunity for redemption can be personally experienced (St. Augustine) or societally imposed, as in the case of Raskolnikov, whose mental anguish ultimately leads to his confession and redemption, albeit in the literal purgatory of Siberia.

Thus, the path leading to redemption is rarely smooth and may not even be successful, as in the case of Eugène Marais, the Afrikaner polymath who, alone in his hovel, observed, documented and wrote about apes for three years in their native context—resulting in his The Soul of the Ape (1969, English edition, but actually written in the 1920s)—while musing about his ingestion of morphine to which he was addicted and led him to clearly understand that ever-greater amounts of morphine were required to achieve the same level of momentary mental elation.

I read Soul of the Ape in Heidelberg, Germany, as a soldier in the US Army, at some point during the time I was stationed there (1970-1971). Marais clearly understood that there would come a time when the amount of morphine required would surpass the body’s ability to withstand it, but he did not live to witness and attest to that principle. At 65, he took a shotgun and shot himself first in the chest and then the head.

Marais’ anguish and insights did not lead to confession and, therefore, there was no redemption, only despair and the emptiness of a tragic death. Drug addiction, nevertheless, is not an insurmountable barrier to the quest and realization of redemption.

Thomas De Quincy’s autobiographical account, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821), was immensely popular with the public for decades in England and abroad, describing as it did the vast pleasures and marginal pains of addiction. The necessity of redemption was presented as an almost reluctant conclusion by the author-eater. De Quincy considered redemption justified for the sake of, if nothing else, being able to continue to meet one’s professional responsibility and the demands of productivity. He also found it essential to remain in an appropriate physical and mental condition sufficient to appear coherent to others and to engage in sustained social interactions.

In a manner that gives the impression of deception or hypocrisy, or both, De Quincy used confession, forgiveness and redemption as a means to continue to ingest opium as a controlled substance, while eloquently claiming or charmingly suggesting that his use was in the past. His was a cycle of perpetual sinning and seeking forgiveness and redemption in order to sin once more, allowing him literary success, moderated opium use, and selective redemption.

When I first read Carlos Castaneda’s (I am spelling his last name without the tilde-ñ, as that convention has been used in his books; others may prefer to spell it Castañeda) The Teachings of Don Juan, I completely missed the point of its subject matter. Yes, I know that there was a subtitle, but I overlooked it because I was in the library at Ft. Huachuca, Arizona, after Basic Training at Ft. Bliss, Texas, and now involved in learning Morse code. Since May 1969, I had been experiencing life in the Army as a draftee during the heavily contentious Vietnam War.

The author with his mother and older brother, Art, in San Antonio, while his father was serving in WWII

The author with his mother and older brother, Art, in San Antonio, while his father was serving in WWII All of them were essentially, to greater or lesser degrees, about the perennial triad of sin, forgiveness and redemption, and in Seville, no less! I share all the above thoughts that came to my mind to say that I was desperate for a Spanish-related cultural injection—a cultural fix—so I confess my error and beg forgiveness.

Nevertheless, as we are prone to sense or know, coincidences are merely unforeseen experiences that were meant to take place. Thus, not at all coincidentally, reading The Teachings of Don Juan was a major cultural fix for me, for it altered my mind in ways I had not experienced previously. Moreover, it was a transformative experience for me, for I internalized immediately two life-long lessons:

First, to respect and honor as a legitimate cultural value and behavior the ingestion of mind-altering natural elements by groups, within their native context, for purposes integral to the group’s codified well-being; and,

Second, to avoid ingesting those types of drugs outside a legitimate cultural context and without a competent guide a la Don Juan.

I didn’t see the United States—the dominant cultural model or any of its less-dominant groups—as having a legitimate cultural context or knowledge-base for drug ingestion and never felt the need for drug use for recreational or “psychology-of-insight” purposes. I had made a marked distinction between cultural values and behaviors associated with the belief system of a group, as opposed to individuals who belonged to a group culture but whose practices did not emanate from or reflect the core values of that culture.

This is, of course, the time for full disclosure: I do drink red wine moderately, beer occasionally, tequila reposado—or at times, añejo/añejado—if either is in front of me, and, albeit rarely, I enjoy a straight—no ice, no water—bourbon/whiskey, never the Jim Beam taste, if the occasion arises, which it very rarely does. As this statement regarding alcohol consumption is not a confession, I do not seek or care about redemption or forgiveness, or consider my way of being, in this case, a sin.

My sin, as will become clear, was one of massive professional blindness and ignorance toward the very group that I had returned to the United States to work for and with, in pursuit of a deeply-rooted and life-long sense of social justice. I had a modicum of, but not directly relevant, academic preparation in the study and intellectual pursuit social justice, having graduated with a degree in Latin American Studies, Social Sciences, from the Universidad de las Américas. My cultural context, both in Seville, Spain, and Mexico City, Mexico, was far from the context in which I desired to participate in and contribute to. I just didn’t realize it at the time—that is, all my life up to then.

In the 1960s, the university was located a short distance from the exit of Las Lomas de Chapultepec, the massive, mega-élite, mansion-dense neighborhood—specifically at kilómetro 16 de la Carretera México-Toluca. Ambassadors, Cantiflas, politicians, bankers, and others considered the crème-de-la-crème resided in this élite colonia, and so did I, but as a student, in a beautiful residence where they took in student and professional boarders.

At that time, mid-1960s, our university campus was, as I remember, characterized mainly by deep ravines and panoramic views of tree-dense, rolling hills—especially visible from the massive terrace of our small campus, itself, a converted country club. Its student body was a mixture of high-wealth, native-born students, in the main from Mexico City, with groups of foreign students, from the United States, Canada and Europe.

The campus was, in part, an extension of the relaxed life-style of the rich and famous, where high-end cars were visible, driven by students in tailor-made suits or casually fashioned outfits. At the same time, there were the American students who would come for their “quarter abroad” programs, wearing chinos, sockless loafers and madras shirts—who never really fitted in and whose presence appeared more decorative than substantive. They were like silent, colorful, moving units amidst a socio-cultural context that at times saw them but did not engage with them.

There were more serious foreign students, who either could not or preferred not to adapt to the Mexico City culture and left soon after arriving; or native students, who decided to transfer to the internationally prestigious Colegio de México, a highly regarded research university that specialized in the social sciences. There were also those who came looking like the perfectly groomed upper-middle class students they were back home and soon after experimenting with easily accessible pharmaceutical and other mind-altering substances, abandoned their grooming, previous dress codes, and normative behavioral façades, preferring to, as Timothy Leary so famously declared: “Turn on, tune in, drop out.”

It shocked me, literally, to have embraced friends, socialized and laughed with them, only to see them fade into themselves and ultimately disappear from campus. I knew it was due to their drug use, but I did not probe deeper than that and it did not touch me or my particular group of friends—at least not during the time we were completing our undergraduate degrees.

This early, indirect experience with the effects of drugs on a few of my friends and other students visible to me led me away from any intellectual arguments in their favor and, as I mentioned above, after reading The Teachings of Don Juan, I confess that my personal attitude toward recreational use of mind-altering drugs or their use outside of an authentic context native to the culture solidified even more.

Ultimately, regardless of where I had lived; what I had experienced; what I had read for pleasure or studied formally; the Spanish I had been exposed to from birth and developed in Spain and Mexico; the values, principles, thoughts, desires and dreams I had of working within the arena of class struggle, of social justice, and of societal change were not sufficient in preparing me for the setting in which I would soon enter: the Chicano context of San José, California.

Archives

April 2024

February 2024

November 2023

October 2023

January 2023

December 2022

October 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

March 2022

February 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

June 2021

April 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

October 2019

August 2019

July 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

March 2017

December 2016

September 2016

September 2015

October 2013

February 2010

Categories

All

2018 WorldCon

American Indians

Anthology

Archive

A Writer's Life

Barrio

Beauty

Bilingüe

Bi Nacionalidad

Bi-nacionalidad

Border

Boricua

California

Calo

Cesar Chavez

Chicanismo

Chicano

Chicano Art

Chicano/a/x/e

Chicano Confidential

Chicano Literature

Chicano Movement

Chile

Christmas

Civil RIghts

Collective Memory

Colonialism

Column

Commentary

Creative Writing

Cuba

Cuban American

Cuento

Cultura

Culture

Current Events

Dominican American

Ecology

Editorial

Education

English

Español

Essay

Eulogy

Excerpt

Extrafiction

Extra Fiction

Family

Gangs

Gender

Global Warming

Guest Viewpoint

History

Holiday

Human Rights

Humor

Idenity

Identity

Immigration

Indigenous

Interview

La Frontera

Language

La Pluma Y El Corazón

Latin America

Latino Literature

Latino Sci-Fi

La Virgen De Guadalupe

Literary Press

Literatura

Low Rider

Maduros

Malinche

Memoir

Memoria

Mental Health

Mestizaje

Mexican American

Mexican Americans

Mexico

Migration

Movie

Murals

Music

Mythology

New Mexico

New Writer

Novel

Obituary

Our Other Voices

Peru/Peruvian Diaspora

Philosophy

Poesia

Poesia Politica

Poetry

Politics

Puerto Rican Diaspora

Puerto Rico

Race

Reprint

Review

Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales

Romance

Science

Sci Fi

Sci-Fi

Short Stories

Short Story

Social Justice

Social Psychology

Sonny Boy Arias

South America

South Texas

Spain

Spanish And English

Special Feature

Speculative Fiction

Tertullian’s Corner

Texas

To Tell The Whole Truth

Trauma

Treaty Of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Walt Whitman

War

Welcome To My Worlds

William Carlos Williams

Women

Writing

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed