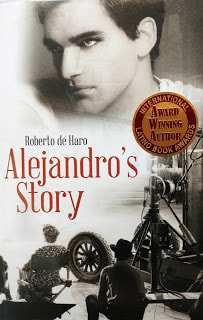

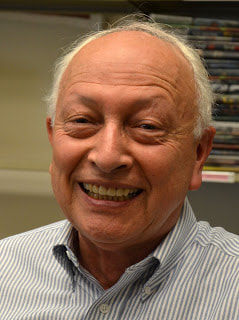

THE CUERNAVACA PAPERS, Part 3On August 2, 2018, what might have been the first encounter between Mexican academics and Chicano writers took place in Cuernavaca, Morelos, México, at the Fifth Annual International Conference on “Latin America: Tradition and Globalization in the 21st Century” hosted by the Universidad Internacional (UnInter), in coordination with St. Mary’s College of Moraga, California. Professor Álvaro Ramirez, a member of the Modern Languages department at St. Mary’s, the organizer of the conference, asked Armando Rendón, the Somos en escrito editor, if he would be interested in assembling a panel to discuss Chicano literature at the conference. Seizing the opportunity for a first encounter with mexicanos on the subject, Rendón invited three Chicanan writers to speak on the nature and scope of Chicanan literature and its symbiotic relationship to Mexico in particular and the Américas in general. In order of their presentations, they were Rendón, Rosa Martha Villarreal, Roberto Haro, and Felipe de Ortego y Gasca. Illness kept Dr. Ortego from attending at the last minute but his colleagues stepped in to discuss the main themes of his essay. The presentations are published here as separate features, but under the title, “The Cuernavaca Papers” La Pluma y el CorazonBy Roberto Haro The northward movement of Latinos from Latin American countries, and especially Mexico, to the United States caused the development of a literary subculture that continues to evolve. A significant part of this process is the creation of a window, a portal through which the Latino community views the larger society, and where America can also see into the Latino community and culture. While other ethnic and racial groups in the US have influenced American literature, only one or two have created a unique window through which the expression of ideas and emotions is available for comparison and exploration by the country of origin and the immigrant nation. Non-Latino American writers like Maxine Hong Kingston, Sherman Alexi and James Baldwin come to mind as new world writers that explore the intermix of native and different/ external cultures. Yet, for the most part, the unique, viable and impressive Chicano subculture remains tangential to traditional American historians, literary scholars and critics. They do not fully understand or appreciate the important subculture that reflects Mexico and how it has joined with American social and cultural factors to construct a new identity; the Chicano. While the different US environments and provincial cultures influence and condition that identity, there is an overarching communality in America that binds together Chicano society and culture. And Mexican antecedence plays a major role in the development of this identity.  Just down the road from UnInter sits this capilla; dating to early 1500s Just down the road from UnInter sits this capilla; dating to early 1500s There are numerous terms now used, some for political convenience like Hispanic, to identify the Chicano. Labels like Spanish-speaking, Mexican American, Hispano (used in New Mexico and Colorado), and even the comprehensive Latino and Raza exist. However, Chicano is a preferred term for several reasons that will not be explored here. Suffice to say that it remains the most popular identifier because of the ideological message it carries. Mexico among the world’s nations developed a unique literary identity that examines with intense scrutiny what it means to be Mexican. In the Americas, from colonial times until the late 1960s, North American scholars and literary critics favored and praised writers who emulated the literary traditions of the Iberian Peninsula. But gradually, Latin American writers and poets, like Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel Garcia Márquez, Juan Carlos Onetti and Pablo Neruda were recognized and celebrated for their new literary perspectives. In Mexico, Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes prepared impressive works that revealed a new literary orientation and style built not on European values, but on those of the people of the Americas. The unique literary expression of Mexico was carried north to the United States by Mexican immigrants. Gradually, the immigrants who traveled north made a place for themselves in the US and began to express in voice and printed word their experiences. However, the writings of Chicanos have not received the attention and consideration of social scientists and literary scholars in both countries, especially in the fields of literature and communications. So far only a few prominent Mexican writers, like Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes, ventured impressions, images and narratives about the experience of Mexicans in the US. What it means to be Chicano (male and female) in the US can be traced to the preliterate expression of Mexican immigrants using graffiti to communicate ideas and feelings, and to musicians who sang about their experiences. The corridos were musical expressions by Chicanos that told stories about their lives in the US. Gradually Latino poets and writers started to formalize their thoughts and feelings to represent their status in the US. As Chicanos were a minority in America, their early expressions often were cautious forms of self-identity and impressions of what it was like to be marginalized by a dominating culture. However, some Chicano writers like Oscar Zeta Acosta and Raul Salinas used indirect aggression in their writings to challenge the larger society that ignored or repressed Chicano literary expression. The image of the Chicano could not be suppressed, however, and in his seminal work, I Am Joaquin,” Corky González described what it was to be Chicano. Luis Valdez in a theatrical mold used the image of the Pachuco to convey a similar theme, albeit as an evocative persona in a fixed time. There followed Chicano poets like Alurista, building on the contributions of artists like Corky Gonzalez and Luiz Valdez, writing with a new sense of urgency and using colorful and passionate terminology that added to the mystique of the Chicano as a new American person. Writers like Rudolfo Anaya and Sandra Cisneros contributed to the narrative and gradually made important gains and recognition among a wide audience and thereby influenced traditional US scholars and literary critics.  Over the years, Chicanos moved past simple graffiti to murals, oral and written music, and then to poetry, essays and other forms of literary expression to forge their identity. The advent of new sources of media, film and audio recordings, expanded the avenues for the projection of Chicano self-identity. Films like Tortilla Soup are important visual dramatizations of the emotions, sentiments, language and social behavior of Latinos and Latinas that graphically dramatize the Chicano family in today’s America. While films like Tortilla Soup are infrequently prepared, there is a growing appreciation by movie moguls that a large and expanding Chicano audience is ready to pay to view films about their experiences in America. However, the dissemination of Chicano ideas, especially in literary narrative, is not well served by the publishing industry, traditional communication outlets, and the media. Latino writers continue to be marginalized, especially by white editors and literary critics. These traditional gate keepers in the publishing industry continue to favor simpering memoirs and formulaic mysteries and detective stories (particularly spy thrillers and international intrigue novels), and occasional sops about the “immigrant experience” in America that are sanitized for the average American reader. While self-publishing, the internet, and a vigorous expansion into radio and TV have helped Chicanos, many challenges remain that limit the full dissemination of Chicano literary expression and the rich culture on which it is based. What can Mexico and the United States do to promote the identification, preservation and dissemination of ideas, feelings and experiences of Chicanos in the US? We need to hear more from writers like Michael Nava, Maria Nieto and the creative Rocky Barilla. These three authors are examples of inventive, talented and award-winning Chicano spokespersons. They have engaging stories to share about Chicanos and their lives in America. It is essential, therefore, that a form of cooperation exist among literary scholars and social scientists in both countries to share and understand the unique writings and communication of Chicanos that benefit all people. Moreover, it is imperative that the media and publishing gatekeepers recognize and respect the work of progressive advocates like Kirk Whisler and his important creations: The International Latino Literary Awards and Latino Books into Movies competition. When combined, these efforts promise a full and rich interpretation of what it means to be Chicano, and how our lives have played a very significant role in the history of the United States.  Roberto Haro, who writes under the pen name, Robert de Haro, is a retired university professor with a doctorate in higher education administration and public policy and career service as a senior level academic administrator at major universities in New York, Maryland and California, His 13 novels to date, many of them award-winning, employ historical fiction between 1900 to 1950, contemporary detective yarns, and tales about the Mexican American experience in the United States. He resides in Marin County, California.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ArchivesCategories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

Somos En Escrito: The Latino Literary Online Magazine

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

©Copyright 2022

RSS Feed

RSS Feed