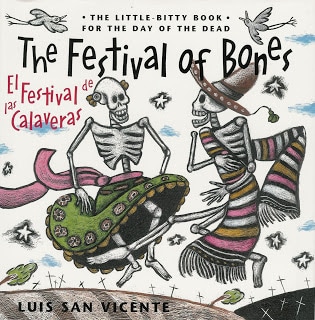

Why are these guys staring at me?Excerpt from Harmony of Colors, a novel by Rocky Barilla Chapter 1 – The New Kid Wednesday, September 20, 1961, 3:10 p.m. Franklin Junior High School The after-school mariachi class had just begun at Franklin Junior High School. The instructor, Mr. Padilla, was oblivious to the two new people just entering his classroom. The petite woman, wearing a grey business suit highlighted by pearl stud earrings, approached with a slight limp. This was the principal, Aileen Yoshida. She was escorting a student toward the teacher. “Excuse me, Mr. Padilla,” she said in a very authoritarian tone as she handed the music teacher a yellow slip. “You have a new student.” Mr. Padilla looked at the new student and then glanced at the class enrollment form. The principal abruptly spun around and exited the classroom. The teacher pushed up his glasses and paused for a moment. ¡Ay Dios mio! He muttered under his breath, one more student! In front of him stood a five foot-four, ebony-skinned youth with a jet Afro. Luis bent over toward his cousin and whispered to Miguel, “What’s he doing here?” Miguel shrugged his shoulders to show that he didn’t really know. “He’s a negro, primo,” Luis said in Spanish. “He’s in the wrong class!” The new kid’s head momentarily turned in their direction. * Ten minutes earlier the school bell had rung, dismissing most of the pint-sized students from Franklin Junior High School in the central section of the San Joaquin Valley of California. The torrid heat assaulted them as they exited the air-conditioned rooms. The youngsters squawked and squealed and teased one another. The third day of the new school year was over for most of them. What had happened to their summer vacation? But for a few, the educational process continued. Over by the administration building, there was a beige portable classroom where a handful of students filed in. Some were carrying musical instruments. Others were not. Most seemed to be of Mexican background. “Okay! Okay!” Mr. Padilla addressed his students in a commanding tone. “Please take your positions.” The forty-year-old Enrique Padilla was just starting his eighth year of teaching music at Franklin Junior High School. These students had signed up for his after-school mariachi class. Some of them were carryovers from the year before. Everyone loved Mr. Padilla. He could have passed for a modern day D’Artagnan with his curled up mustache and chin patch. “Don’t forget to hand in the forms that I gave you on Monday,” he gestured with his black-framed round glasses. “Only one form if you have your own instrument. Make sure that your father or mother signs it. The green form if you are borrowing a musical instrument.” The students passed their forms forward and one student got up and placed them on Mr. Padilla’s desk. The teacher gave the new arrival two forms. Ángel walked over to an open seat. “Mr. Padilla,” a student raised his tiny hand. “I forgot my form.” The teacher looked at the short, skinny boy with the crew cut. He shook his head. ¡Ay Dios mio! “Okay, Rafa,” he stared at the youth. “Bring the forms in on Friday.” The eighth grader Rafael “Rafa” Dominguez nodded his head as he pulled down on his white tee shirt. Mr. Padilla picked up a clip board and took a pen out from his plaid vest pocket. “I’m going to take roll call,” he said when he realized that a few students from Monday’s class had not shown up. The first week of class was always chaotic, he thought. “Miguel Nava!” “Here!” shouted out the 13-year-old first violinist. He had been one of Mr. Padilla’s students from the prior year. Miguel sported a barely perceivable peach-fuzzed moustache. “Lisa Nava!” “She’s not here,” her older brother Miguel jumped in. Lisa was Miguel’s younger sister who was the vocalist for the group. She actually did not play a musical instrument, but sang some of the mariachi songs. Unlike her brother, she had not participated the year before and was still debating whether or not she was going to join the group. “Luis Salcedo!” Mr. Padilla continued. “Here!” yelled out Miguel’s cousin, Luis “Güero” Salcedo. He was nicknamed “Güero” because of his light skin color. It was hard for most people to discern that he was Mexican. Next, Rafa replied in the affirmative. “The new student,” the teacher barked out. “Ángel Prieto!” “Prieto!” roared out Luis laughing. “Mr. Salcedo!” admonished the teacher. “You’re the one that called him ‘prieto’.” “That’s his name!” barked Mr. Padilla. The new boy was the center of glaring attentions from the other students. All the kids were Mexican except for the White guitarist Randy Reynolds. Ángel’s dark brown eyes shifted from side to side. It was his first day in a new school. He was fairly new to this country and to the town of Donaldson – far, far away from where he was born. His palms were sweaty and he felt all the anxieties that only a 14-year-old boy can feel: the lack of self-confidence, worries about his appearance, and the apprehension at having to interact with kids who might not like him. Ángel kept looking around. Brown faces (except maybe for one or two) looked back at him. He didn’t say anything. Why are these guys staring at me? “Class, please, settle down,” admonished Mr. Padilla. The teacher resumed the roll call and checked off the names of Mateo “Gordo” Pacheco, Jorge Lopez and his brother Pedro “Pito” Lopez, and Randy Reynolds. It seemed that five students had dropped out since Monday’s class. Mr. Padilla paused for a moment and then came back from his distraction. Something was bothering him. “Okay, listen up, class,” the teacher shuffled some papers. “We are going to review the assignments. Let me know if you still need to borrow a musical instrument.” They went through the class list and set up the musician assignments: Miguel Nava, first violinist, has own instrument Rafael “Rafa” Dominguez, second violinist, needs to borrow Mateo “Gordo” Pacheco, guitarrón, has own instrument Jorge Lopez, vihuela, has own instrument Pedro “Pito” Lopez, flautist, has own instrument Randy Reynolds, guitarist, needs to borrow A controversy arose when Luis “Güero” Salcedo said that he was the trumpeter and needed to borrow the school’s trumpet. Ángel who had remained invisible during the inventory said softly, “I play the trumpet.” The class seemed shocked. They realized that he spoke strangely. He had some kind of foreign accent. “But I don’t have one,” Ángel stuttered. Mr. Padilla walked over to the musical instrument closet. After rummaging through it, he came up with an old trumpet. He handed it to the new arrival. “Please try it out, Mr. Prieto.” Ángel started to finger a few notes, but one of the valves kept sticking. Mr. Padilla retrieved the trumpet. He paused for a second. “Mr. Salcedo and Mr. Prieto, you will have to share the other trumpet. Luis please hand him the trumpet.” Luis frowned. Everything had been settled on Monday. He had played the trumpet with the class the year before. Why did this negro kid have to spoil everything? He thought angrily. “Okay, Mr. Prieto, try this one,” instructed the teacher. Ángel fingered the trumpet again. He was not great, but showed a basic knowledge of the instrument. “Okay, now you, Mr. Salcedo,” Padilla motioned for Ángel to give back the trumpet to Luis. “But he put his nigger lips on it,” Luis cried out. “Mr. Salcedo, shame on you!” Mr. Padilla’s face was red. “We don’t use such language!” Ángel’s dark brown eyes grew larger. Why is this guy giving me a bad time? “Any such language again and I will kick you out of class. That goes for everybody. Does everyone understand?” The teacher was furious. The class was silent. The students didn’t know how to react or what to say. Mr. Padilla grabbed Luis by the shoulder. “Take the mouthpiece to the bathroom and run some warm water through it. Do you understand?” Luis nodded his head “yes.” “And don’t forget to dry it.”  Rocky Barilla, a Los Angeles native, specialized in migrant legal aid and immigration law, then taught in Oregon law schools. From 1979 to 1985 he worked as a staff attorney on various committees of the Oregon Legislature, then in 1986, became the first Latino elected to the Oregon Legislature, representing South Salem. He authored HB 2314 (1987), now known as the Oregon State Sanctuary Law. After moving to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1988, he worked for the California Teachers Association for 21 years and more recently with California Rural Legal Assistance. He is author of several award-winning books, including his latest, “A Taste of Honey.”

0 Comments

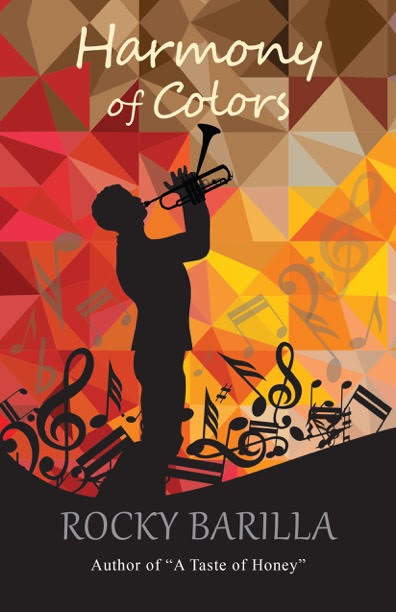

They call me guëro Border Kid It’s fun to be a border kid, to wake up early Saturdays and cross the bridge to Mexico with my dad. The town’s like a mirror twin of our own, with Spanish spoken everywhere just the same but English mostly missing till it pops up like grains of sugar on a chili pepper. We have breakfast in our favorite restorán. Dad sips café de olla while I drink chocolate— then we walk down uneven sidewalks, chatting with strangers and friends in both languages. Later we load our car with Mexican cokes and Joya, avocados and cheese, tasty reminders of ourroots. Waiting in line at the bridge, though, my smile fades. The border fence stands tall and ugly, invading the carrizo at the river’s edge. Dad sees me staring, puts his hand on my shoulder. “Don’t worry, m’ijo: “You’re a border kid, a foot on either bank. Your ancestors crossed this river a thousand times. No wall, no matter how tall, can stop yourheritage from flowing forever, like the Río Grande itself.” Borderlands Sixty miles wide on either side of the river, my people’s home stretches from gulf to mountain pass. These borderlands, strip of frontier, home of hardy plants. The thorn forest with its black willows, Texas ebony, mesquite, huisache and brasil. Transplanted fields of corn and onion, sorghum and sugarcane. Foreign orchards of ruby red grapefruit white with flowers. Native brush rainbow bright with purple sage, rock rose, manzanilla and hackberry fruit. Beyond its edges spreads the wild desert, harsh and lovely like a barrel cactus in sunny bloom. Checkpoint On our road trip to San Antonio for shopping and Six Flags, Dad slows the car as we approach the checkpoint, all those border patrol in their green uniforms, guns on their belts. Mom clutches los papeles—our passports, her green card. She’s from Mexico. A resident, not a citizen, by her own choice. At the checkpoint a giant German Shepherd sniffs the tires as the agents ask questions, inspect our trunk. My little brother squeezes my hand, afraid. My rebel sister nods and says her yessirs, but I can tell she’s mad, the way her eyes get. We’re innocent, sure, but our hearts beat fast. We’ve heard stories. Bad stories. A cold nod and we’re waved along, allowed to leave the borderlands— made a limbo by the uncaring laws of people a long way away who don’t know us, a quarantine zone between white and brown. I feel angry, just like my sister, but I hold it tight inside. We just don’t understand why we have to prove every time that we belong in our own country where ourmother gave birth to us. Dad, like he can feel the bad vibes coming from the back seat, tells us to chill. “It won’t always be like this,” he says, “but it’s up to us to make the change, especially los jóvenes, you and your friends. Eyes peeled. Stay frosty. Learn and teach the truth. Right now? What matters is San Antonio. We’ll take your mom shopping, go swimming in the Texas-shaped pool, and eat a big dinner at Tito’s. Order anything you want.” And he slides his favorite CD into the battered radio. Los Tigres del Norte start belting out “La Puerta Negra”-- “Pero ni la puerta ni cien candados van a poder detenerme.” Not the door. Not one hundred locks. Ah, my dad. He always knows the right song. Our House Our house wasn’t ready all at once. Our house took years to grow, like a Monterrey oak gone from acorn to tall and broad and shady tree. My parents saved for years, bought a nice lot on the edge of town, drew up the plans with Tío Mike. One year the family poured the foundation, then the next these concrete walls went up. Atlast my father built a sturdy roof, and in we moved, finishing it room by room, everyone lending a hand, every spare penny spent para hacernos un hogar-- a home that glows warm with love. Now it’s like a bit of our souls has fused with the block and wood. I can’t imagine life without this place— on these tiles I learned to walk. Here are my height marks, with fading dates, higher and higher. Oh, all the laughs and tears we’ve shared at that table! All the cool movies we’ve watched sitting on that couch! And here’s my room, filled with all my favorite stuff, sitting in the shade of the anacua tree I once helped to plant. A modest home, sure, but inside its cozy walls we celebrate all the riches that matter. Pulga Pantoum Mom and I love to go to the pulga, to get lost in the crowd that flows between all the busy stalls, drawn to colors, sounds, and smells. To get lost in the crowd. That flows from our instincts, I bet. Humans are drawn to colors, sounds, and smells like a swarm of bees to blooming flowers. From our instincts, I bet humans are happiest together. Bulging bags in hand, like a swarm of bees to blooming flowers, people meet for friendly haggling. Happiest together, bulging bags in hand— Mom and I love to go to the pulga! People meet for friendly haggling between all the busy stalls. Fingers and Keys My mom’s the organist for our parish-- One of the last, she says. When I was little, she taught me to play on a worn-out old upright that stands in a corner of our dining room, holding up family photos. Even though I’m twelve now, when I sit down to practice, laying my hands upon the keys, I sometimes feel her fingers on mine light as feathers but guiding me all the same. Lullaby Like lots of border kids, my first song was a lullaby that my abuela sang to warn me and to mystify. My mom says when I got home, smiling without teeth, she took me in her arms and serenaded me-- Duérmete mi niño Go to sleep, my baby duérmeteme ya sleep for me right now porque viene el Cucu to keep Cucu from coming y te comerá. and swallowing you down. Y si no te come, And if he doesn’t eat you él te llevará he’ll take you far from me hasta su casita to his little cabin que en el monte está. that sits amid the trees. So I learned the dangers of this crazy, mixed-up place— there are monsters lurking, but family lore can keep you safe. Learning to Read When I was a little kid, my abuela Mimi would ease down into her old, creaky rocking chair to tell my cousins and me such spine-tingling tales as ever a pingo fronterizo, crazy for cucuys, could hope to hear. I always had questions at the end of Mimi’s stories. What was the little boy’s name? What did his parents do when they found him missing from his room? Is there a special police squad that tracks down monster hands and witch owls and sobbing spirits in order to save the boys and girls that they’ve stolen? “No sé, m’ijo. The story just ends. Happened once upon a time. Nobody knows.” But I didn’t get it. I was so literal. I believed every story she told was true. So I kept asking my questions, guessing at answers till she broke down at last and told me the greatest truth: “You have to learn to read, Güerito. You will only find what you seek in the pages of books.” So I began to bug my mom to teach me to read till she did. I was barely five at the time. First day of kinder arrived, and I was so excited at all the books my sister said were waiting on the shelves for me. But then the teacher started drawing the letter “A” on the board, and I soon got it— none of the other kids could read. She was going to teach us the alphabet one letter per day! Not me! No way! I dropped out of kindergarten, little rebel that I was. Instead, my mom took me to the public library every day, all year long. I read book after book after book delighting in the new tales, the strange and mysterious places. And when first grade rolled around (not optional like kinder), the school was so amazed at my skill they put me in a third-grade reading class! I got picked on, sure, but I was pretty proud and didn’t care when kids called me nerd. The school counselor told my folks I can already read at college level! And I’ve found lots of answers, but also many new questions. Of course I pass all the state tests with super high scores. Learning in class is easy for me. Dad says all those books rewired my brain, got me ready for study. Just think-- I owe it all to those stories my abuelita used to tell us sitting in her rocking chair as we shivered and thrilled. Even then, words were burrowing into my brain and waiting, like larvae in a chrysalis, to unfold their paper wings and take me flying into the future.

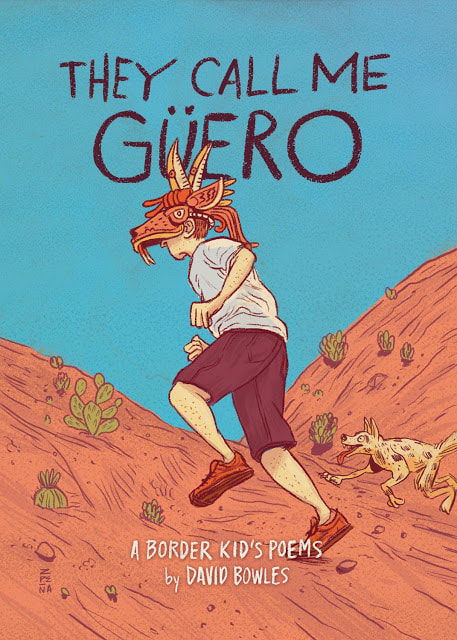

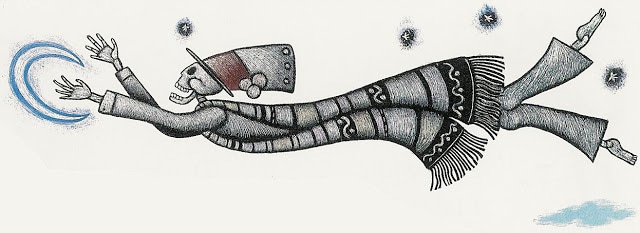

Festival of Bones : Festival de las Calaveras Written and Illustrated by Luis San Vicente Hey, I’m flying! The celebration is so far way… Oh, they want to catch me. Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, fascinates kids in Mexico and the U.S.A. With fantastic illustrations and a wild and fanciful poem, Luis San Vicente captures the spirit of this most marvelous day in this classic essay, directed toward young readers, which explains this important Mexican tradition, and the fun things kids can do to join in the festivities.  We thank Cinco Puntos Press, publisher of Festival of Bones, for allowing us to feature a few of the illustrations of this classic work, just in time for the festivities. Check it out at FestivalofBones. Translation by John Byrd and Bobby Byrd.  Luis San Vicente is a Mexican artist who studied at the Autonomous Metropolitan University in Mexico City and has exhibited his works in Mexico, Venezuela, Europe and the U.S.A. UNESCO awarded him its prestigious NOMA Encouragement Concours Prize for Illustration and honored his work in their prestigious Youth and Children’s Catalog of Illustrations (1997, 1998 and 1999). The Beginning of the End of the Beginning By Tommy Villalobos Oro was a big-hearted but nosey critter who stuck his nose all over the place and wore big ugly cravats. He liked making buddies and he had many. One late afternoon he ran into Elo who had no idea what a “buddy” was. The manner of their encounter is worth recounting. Elo spotted a half-eaten fast-food burrito and was sniffing toward it, in no hurry since his mistress had just fed him a sizeable cena. However, from the opposite direction came two mangy dogs and a very large mutant rat with a flowing white beard, all three of the blighters (Elo was part English Foxhound) were strutting with an attitude reminiscent of ravenous wolves in a frigid corner of the Arctic. To them, Elo was a small and sniveling Arctic fox who had overstepped his boundary. They began their growling in unison. Elo looked to the sky for thunder clouds, never having heard such rumblings from any source. While his throat was exposed, the large bearded rat leaped for it. Just then Elo dropped his head and, as a result, got his schnoz chomped on by the bearded rat. This caused Elo to emit a mighty yelp. Then the other two joined in, snipping at his body. Elo had never been around dog-eat-dogs, much less rats with grandfatherly appearances, and didn't know where to turn, but in one of his turns, he saw another, large frazzled dog approach, the most revolting of the lot. He had a massive head which he had twisted into a menacing image of slobbering and threatening terror. He was viciousness within viciousness. He followed with the gravest and deepest rumble Elo was certain had ever been rumbled. This ugliest of brutes looked like the ring leader that was about to finish him off. He closed his eyes, thinking of his mistress whose angelic face he would never again smother with happy licks. Then he heard the most unearthly cry and ciphered it was he who was yelping his last. Then a second wail of agony, followed quickly by a hideous squeal. Elo opened his eyes to witness Mr. Rat Creature airborne then immediately earthbound, landing on his big head, several rapid head thuds propelling a fair piece down the block. He uprighted himself and using the momentum graciously provided by the beastly thing, continued scampering down the block, his white beard the last of him to dissolve into the surroundings. He was hoping there was a doggie heaven, for he then collapsed on the pavement. He knew he was breathing his last. Too bad, for his final breath would be of a fast food burrito and not of the delicious meals his mistress prepared for him highlighted by her sweet scents. His eyes closed, he heard sniffing around him. They were ready for their meal. Then he felt a wet nose, followed by a wet tongue. “Get it over with, you filthy thugs, you horrid scum of Hades! Why torture me?” he yelled. After this, there was no more sniffing or licking. He opened one eye, then another. Only the terrible dog remained. The repugnant creature looked at Elo with indifference before continuing on to the burrito. Elo noticed that all the unpleasant chaps from earlier were gone. He ventured to rise and walk toward the horror in the form of a dog who was not interested in devouring him after all. The tan beast was Oro who hadn't eaten a respectable meal in two days and who always became somewhat of a monstrosity when having missed any amount of meals. His movement toward the burrito was urgent and with snarling care. Elo walked after him, tail wagging. Oro turned as Elo approached and, yes, they actually bumped cabezas. Oro snarled with yellowojos, Elo stepped back, puzzled. He had never heard so much snarling over food. Of course, his only experience was eating quiet meals with his mistress at home. And she never snarled at all. Oro swallowed most of the burrito in two quick gulps. There was a cachito left and Oro looked at Elo. Oro had never met a critter like this before on the streets. No growl, no “gimme some,” no sneaky movement toward the last bite of the burrito. In short, none of the rapacious covetousness that he was used to seeing in the vast majority of the neighborhood denizens. He just looked puzzled. So it wouldn't surprise anyone who knew Oro that after that final bite, he immediately went over to Elo, a being who was shy but happy, and wore a plain collar, grabbed and hugged him and said, “Let's be buddies. Not just for now or a week, but for a lifetime.” Elo had to mull this one over in his relatively small mind. He had never been buddies with anyone and felt no need to start now since he had his mistress and she was enough for him. An offer of a lifetime commitment was something he had never considered. “Do you really mean for our whole lives, yours and mine?” said Elo, scratching behind an ear with a forepaw, clearly confused by the foreverness of affairs. “That's exactly what I mean.” “I never knew anyone who wanted to be my buddy for a long time. In fact, I never knew anyone who wanted to be my buddy for any amount of time.” “Well, buddies we are,” said Oro. “Not to change the subject but whatever happened to your left ear?” said Elo. “Why?” “Because the top half looks like it was clipped off by serrated scissors.” “It was.” “It was?” “Yes, but not by scissors but by a mentally disturbed raccoon. I thought he was the funniest looking critter I had ever seen and I told him so. He took it personally.” “But how else could he take it?” “Well, anyway, one word led to another; he called me a perro chato with no bite and I called him a coyote with a mask and tried to prove it by immediately removing his mask.” “You thought the raccoon was a coyote wearing a mask?” “I did. And I was going to tear it off. Well, he began yipping and yapping but not like a coyote but more like a hyena. It was then that he bit off part of my ear.” “He thought it was fake?” “No, I think it was more because, like I said, he was crazy.” “Oh.” “By the way, my name is Oro because one of my masters, I forget which one, maybe it was James, no, it couldn't be James….Anyway, he thought my coat looked gold at a certain angle. What's your name?” “Elo. It was Elote at first but it was shortened to Elo after only a week.” “Why would they name you Elote? What have you got to do with corn?” “I don't know. I never thought about it.” Incidentally, Oro was a German Sheppard and Elo was a hound of uncertain parentage. To each other, they were two dogs and glad of the fact. Oro was between masters, the last one having moved away without leaving a forwarding address; while Elo had merely wandered from his house and couldn't smell his way back. This frustrated him to no end since he was, after all, a hound, although as mentioned, of uncertain parentage. Oro found this amusing to no small degree. “I never knew a hound who couldn't smell his way out of any problem.” “Well, you've met him.” “Does your mistress live in the Hood?” “What?” “Oh, man, you are lost. I mean here, the barrio, East L.A.” “I just know I lived and was happy with my mistress and would still be so except that today she left the door open. I saw this little gray cat go by and I wanted to make friends. I went up to him barking a friendly bark. He turned, saw me and took off. I ran after him, seeing how much he wanted to play. We ran for a long time until I pooped out as he ran toward a car and disappeared. I then butted heads with you.” “We're natural buddies. The stars brought us together.” “Stars?” “You never looked at the stars at night?” “I've only looked out of our living room window at night.” “Wow. A wonderful world awaits you,” said Oro, with excitement in his voice. “I suppose you have never smelled fast food blowing in the city air and into your nostrils?” “I guess not. Don't know what you're talking about,” said Elo, perplexity in his voice. “I always wanted to meet someone who knew less than me, or rather nothing at all, evidently,” said Oro, giving Elo a second abrazo that Elo this time thought annoying since he did not think Oro's remark was a very nice remark. Oro then gently pushed Elo a few feet back away from him, gazing on him like a proud father gazes on his child who has just said “¡Apá!” for the first time. “You know,” said Oro, “we can start a new adventure today, me and you.” “We can?” “Sure. What's to stop us? You and I are not tied down. We are not attached to any leash, chain, or rope. You know what that means?” “No.” “Freedom!” Oro tore down the block then stopped when he heard no heavy, open-mouthed breathing behind him. He turned to see Elo still standing at the original spot, now scratching behind an ear with a hind leg. He stopped scratching then stared forlornly around him then at Oro. Oro gingerly walked back to him. He had never met such an uncertain creature. “Don't you want to see the world? It looks like your whole world has been the inside of one casita with one muchacha.” “Yeah, but I'm getting hungry. My mistress always gives me a chunk of this or a pedazo of that between meals. Then she scratches my stomach or behind my ears, cooing all the time.” “Sounds cozy. I feel for you. But the advantages of leading your own life outweigh a handout here, a pat on the head there, dripping syrupy palabras pouring into your orejas . Let me show you.” “I don't know. I'm missing her already. And it's noisy and confusing out here. So much is going on. That confuses me.” This was understandable, for Elo was given to his mistress as a pup and had known only the inside of her house, nothing else. She would take him to the park in the mornings, but she was right behind him, and he knew all he had to do was turn and see her for comfort and a pat on the head. Then they would immediately return home. “But,” said Oro, “I also faced the very same thing. Sure, meeting strangers and wacky cosaseverywhere you turn can be scary. Heck, the first time I found myself in the streets, I scared an elderly woman out of her Nikes, which attracted a group of boys who threw rocks at me. She claimed I was an attack dog that had escaped. Escaped from where, I haven't been able to figure out. But that's the fun of being on the loose and on your own. You encounter odd, puzzling circumstances all the time.” Elo put his head down. The decision that was being laid before him was one he had never been called on to make. His mistress had always made all decisions for him. He did nothing or cared about anything except her. She was his world. She even told him when and where to bark, telling him to “Shush!” whenever he barked at the wrong time or the wrong person. Out here, even barking would be confusing and stressful. “Why don't you help me find home, instead?” “Your prison?” “No!” said Elo in horror, for he could never think of home as prison or his mistress as a warden. “Okay, I spoke out of turn. I just want you to go on a few adventures with me. Nothing major. We will just wander a few blocks this way”—he pointed his snout in one direction—”or a few blocks that way”—he pointed his snout in another direction. Elo followed Oro's snout each time he pointed then pointed his own snout down to the ground, still in the middle of indecision. He felt overwhelmed. “What do you mean when you say 'adventures'?” said Elo. “Well, to put it most simply, you start here, go there then turn here then go back there while you think of going over here or over there while really deciding to go back where you came from. It is the most fun thing to do without a leash yanking you back.” Elo seemed confused. So Oro elaborated. “Adventures are the grandest of things. We go to new and exciting places, meet most interesting fellow creatures. For example, I met a pig just two blocks from here. Not only that, he had a master. Some guy was walking him on a leash!” “Yes, I've heard of them. Pot-bellied pigs. Some people prefer them to us dogs.” With this, Oro heard a whimper come from his new buddy. This was because Elo thought of his mistress and home when Oro had mentioned someone walking someone on a leash. “Tell you what, go with me on one adventure. Just one.” “How long will it take?” “Maybe one hour. Although one adventure I went on lasted over a year,” said Oro with exhilaration in his voice. “That's why everything is interesting because nothing is certain.” This enthusiasm did not transfer to Elo, for he let out another whimper, which actually moved Oro and at the same time gave him grave concern. This hound was a lost cause. “Forget the boredom of certainty,” added Oro. “You need the excitement of uncertainty.” No response from Elo. Oro walked away, expecting him to wander in the opposite direction looking for home. And he would probably find it and his snugly mistress and regular snacks, petting and sweet words. He couldn't blame him. In fact, he detected a hint of jealousy in his own feelings. After all, he, Oro, had no choice but to go on “adventures.” He had no home, no master, no mistress. Elo had a clear choice and he chose the right one—return to the warmth of home and mistress. And so Oro, snout to the ground, went back to business, smelling for a prize scrap, travelling down the block. He continued so for a good while, hoping to find a park where people would leave everything from once-bitten sandwiches to half a ham, something he found one time in Belvedere Park. He began to smell that sweet ham while heavy, competitive sniffing came up from behind him. He turned. “¡Elo!” “You know, maybe a little time with unstable you and unpredictable meetings would be good for me. After all, I've only been away from home only a short while. My mistress probably won't miss me right away.” Oro hugged Elo for the third time. This time Elo didn't mind. The two buddies began by sniffing around a banana peel and toward the setting sun. Author’s Note: These stories are inspired by stories my wife told our son when he was between the ages of 6 and 11 until one day she threw up her hands because our son continued to add characters at a pace that was quickly turning the Oro and Elo stories into a Russian novel.

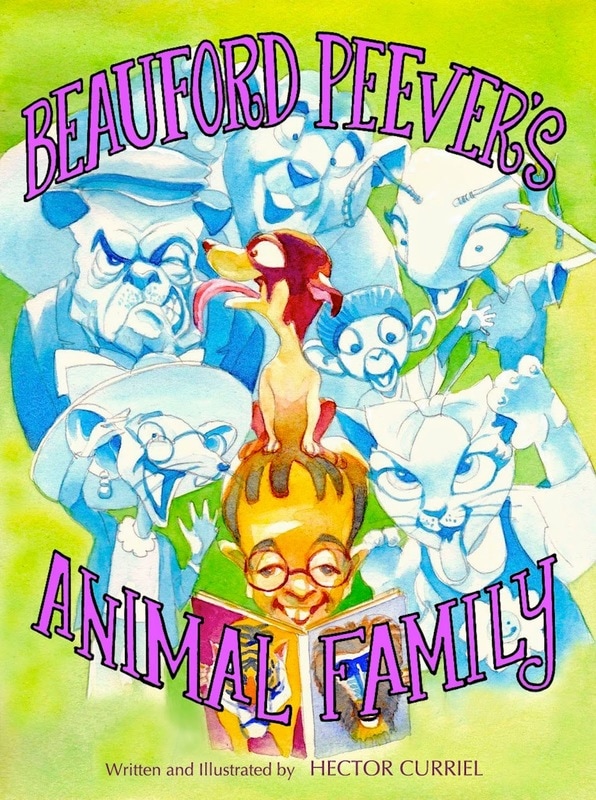

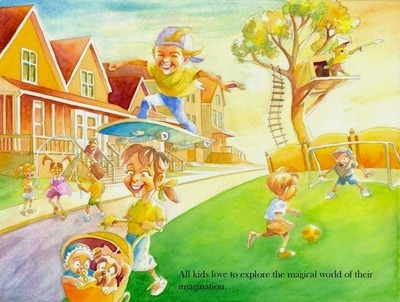

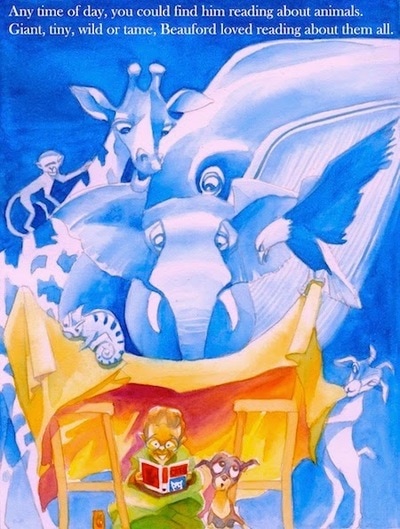

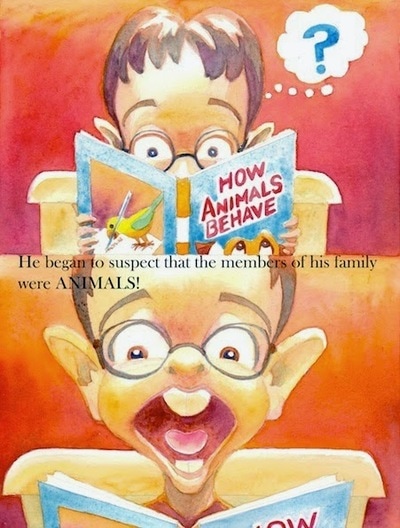

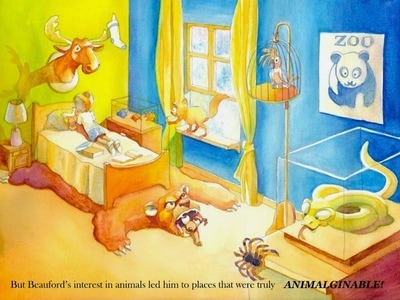

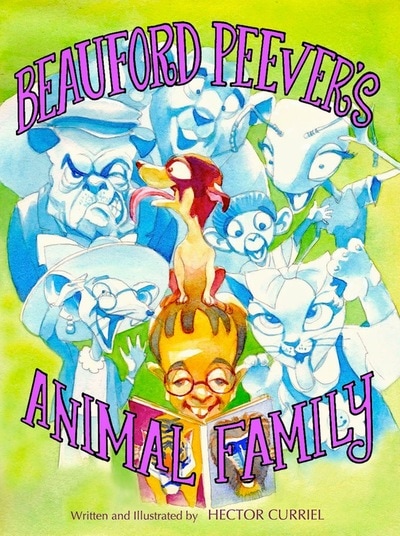

The Birth of El Niño y El Cuento One of the goals of Somos en escrito Magazine is to promote and encourage Latinos and Latinas to write in any genre and just about any topic—children’s and young adult’s literature is one form that deserves special attention. It may seem that there are many books being written for these age groups because we only hear about the award competitions and such, but for years, the percentage of books for and about, and written by, Latinas or Latinos have somehow always fallen below 3 percent. This past January in Austin, Texas, Luis Ramirez, Larissa Dávila and Samantha Ramirez formed Voces Latinas, a non-profit organization—their mission, to consult, support, inspire, implement and boost community groups to fulfill their goals. For example, recently a Central American arts group was bogged down by the State of Texas fee for incorporation, about a thousand dollars. Larissa advised them that by joining a local arts support group they could incorporate for only two hundred dollars. Last February, when they unveiled their “business model” at a community meeting, Erika Martinez,a young mother of two girls, 8 and 12 year-olds, shared her dream of creating a writing competition for children. Her daughters loved to read and to write, she said, but didn’t have many opportunities to receive recognition for their stories. Voces Latinas responded: they founded El Niño y El Cuento, a writing contest for children. “The idea of El Niño y El Cuento was seeded from my daughters’ love for literature and how they can develop their imagination when they create a story. This project was a dream that I sent to the universe with a lot of faith and developed with a lot of effort and it has come back to me with great results,” Erika said. “Voces Latinas decided to support Erika with the contest because we all had a teacher, an uncle, an aunt or a person that pushed us to submit that first story or participate in that contest at an early age and that is what incubates in us the drive to continue writing, and we believe that with El Niño y El Cuento, the children of the Austin community receive that opportunity,” Larissa added. The group found a sponsor and three bilingual judges, Iréne Lara Silva, Jane Garcia and Sandra P. Snethen. The contest was geared for children ages 7 to 10 and 11 to 14 years of age. Manuscripts could be written in English, Spanish or bilingually. Grading was based on Creativity, Technique, and Empathy with the Reader; grammar was not taken into consideration. Children had one month to submit the stories and 78 stories were submitted. The winners received prizes and every child that submitted a work received a Certificate of Participation. Grupo A Primer Lugar: Maria’s Chance – Carmen Saenz, 10 años Segundo Lugar: El Susurro del Viento – Anna Alleman, 7 años Tercer Lugar: La Fresa Magica – Andrea N. Abundis, 8 años Grupo B Primer Lugar: Carla Escribe – Mason Lane Drummond, 11 años Segundo Lugar: The Stars in the Sky – Alexa Klumpen, 12 años Tercer Lugar: El Gusanito Gormito – Carol Villeda, 14 años Editor’s Note: According to the rules, Creativity, Technique and Empathy with the Reader were the critical factors in judging; grammar was not taken into consideration. Against all my editorial instincts, I refrained from making any changes. Readers will discover a beauty and a power of the word in the stories and poems that rise above such technicalities. They should give us heart in the future of our children and the future of U.S. Latino literature. Here are the six new writers’ works: Group A: First Place Maria’s Chance By Carmen Saenz Most of the girls in Maria’s grade thought that she was weird, but really she was just very smart and unique. One day Maria’s grandma, Lita surprised her with a new dress that she had just made. It was made out of a yellow and pink lace. Maria fell in love with it the second she laid her dark brown eyes on it. She was so excited to wear it to school! Maria thanked Lita with a big wet kiss and a loving hug. The next day Maria confidently walked to school with a big smile on her joyful face. Maria’s day was starting off great, until she waved at two girls in her grade and they giggled then whispered something to each other. Of course Maria knew that they were talking about her. She sighed, but told herself to stay positive. Right as she walked into the school doors an older girl named Kate sarcastically yelled “Nice dress!” then gave Maria a snotty grin. Once again Maria sighed and looked to the ground. She was no longer confident about her dress, just embarrassed. Once again a girl in Maria’s class commented rudely on her dress, she ran to the bathroom and looked in the mirror. All of the sudden tears started rolling down her sad face. She was very confused why no one liked her dress. Maria just wanted to be liked. When the bell rang Maria wiped her tears away and headed to class. Mrs. Gonzalez, her teacher asked if Maria if she was ok. “Yes, I’m fine” she answered. So, Mrs. G went on with her lesson. “We have a big project coming up. It is about heritage and culture, your job is to write an essay about where you and your ancestors came from.” She announced. When class was over Maria ran home to tell Lita about the terrible day that she had. Maria tried to start her project, but after a few minutes she realized that she had no idea what to write. Out of ideas, she asked Lita for help. Her grandma seemed very happy to share Information about Maria’s heritage. When they were finished talking Maria took notes and started on her project. She was so lost in her work that she didn’t realize the time! It was past her bedtime. Maria put her pajamas on and jumped into her bed. She closed her eyes, but she couldn’t go to sleep. Even though she was very confident about her project, Maria was afraid that people would make fun of her project, just like how they made fun of her dress. Finally, Maria fell asleep, forgetting that she hadn’t completed her project. In the morning when she was getting dressed she fished through her drawers but couldn’t find anything to wear. Even though she was the one who had picked out all of her clothes only a couple of days back, she couldn’t find anything that wasn’t “old fashion”. When Lita was ready to go she hollered at Maria, but she didn’t answer. When she walked into Maria’s room she saw that Maria was sitting on the ground with her face in her knees. Maria told her about the mean girl Kate. After talking with Maria Lita had an idea. She walked to her closet and pulled out a big brown chest and set it on Maria’s carpet. When Lita opened it, she pulled out several pictures, some colorful fabric, letters and books. When Lita was finished emptying the box she stared into Maria’s big eyes and smiled. Maria closely examined the detailed objects. Lita asked her what all of the items resembled to her. “Family, I guess, and culture.” Maria answered with a puzzled look on her face. Lita nodded and silently passed her a bag of pictures. Maria flipped through them. After a while Maria realized that all of the pictures were of her grandparents. Then Lita softly said, “Maria, this is you. All of this belongs to our family. These letters represent our history, these pictures represent out family, and these dresses represent our culture.” Maria was very impressed about what her grandma had just said. “History, family, and culture.” She repeated to herself. “Good” Lita answered with a nod. Maria was definitely ready for school now. Maria picked up her pencil, thought a minute, and began to write as quickly as she could, full of new ideas for her essay. When Lita dropped Maria off at school she could tell that Maria was going to have a great day. Maria was wearing the same smile that she always did, but this time it was bigger. When she walked into Mrs. Gonzalez’ 5th grade class, she greeted Mrs. G. with a giant hug, and then confidently turned her essay in. Kate was staring at Maria with a disapproving look, and Maria knew that she wasn’t perfect, but she knew who she really was and that’s all that mattered. Later that day Mrs. Gonzalez passed out graded essays. When she handed Maria her paper, she nodded and smiled. Maria nervously turned the paper over, and at the top in big red letters it said A+! Maria was so happy! She raced to Lita and showed her the paper. “I knew you could do it!” Lita joyfully announced. “I couldn’t of done without you.” Maria answered. She gave Lita a big hug and at that moment she knew who she was and she was proud to be herself! She decided to never doubt herself again, and with a smile she gave Lita a big wet kiss! Group A: Second Place El Susurro del Viento By Anna Alleman Puedes oir el viento susurrando lo secretos Que vienen del aire hasta la tierra. Que te giran en la dirección de su destino; Que te hace ver que importa para ti. La dirección de su confianza, pasión, su sentido y amor. Las razones que te hacen a ti el único. Hay un gran mundo y no tanto tiempo para explorar todo, Pero si ves en tu corazón vas a ver que tu futuro cambia pero tu destino no. Escucha Y sentiras el pasto rosando tus pies y el olor del océano, el aire frio y también Caliente, la tierra mojada y también seca. Ves las estrellas que brillan en la noche calmado, cierra tus ojos, respira y ama. Ama la tierra, el océano y el aire. Amor, repítelo amor. Es libre, sin instrucciones, lo mas importante Amor…amor… amor…. Amor esta en el aire, la tierra, el agua y el fuego Brilla…. Brilla… Brilla en nosotros, los animales, las plantas… Brilla…brilla en su destino y en alguna parte del mundo Su destino esta sonriendo ahora. Group A: Third Place La Fresa Magica By Andrea N. Abundis Habia una vez una nina que se llamaba Carolina. Un dia Carolina sembro una planta, el dia siguiente una fresa gigante crecio, le dio un poquito de la fresa a su mascota, la mascota aprendi a hacer trucos de inmediato, pero la mascota no se acabo la fresa. Para la cena tuvieron invitados, los invitados comieron fresa, pero no se acabaron la fresa. Los invitados eran los mejores amigos de Carolina. El siguiente dia la amiga de Carolina la menos valiente ya se hizo super valiente, y la otra amiga que era muy pelionera con otras ninas menos con Carolina , ya no fue pelionera nunca. Carolina se dio cuenta que la fresa era mágica; le aviso a su mama que la fresa era mágica, la mama de Carolina le dijo; ¿ porque no haces una mermelada que puedas compartir con el mundo?. ¡Si, esa es la idea mas padre que he escuchado!!!!!! grito Carolina, pero por mas frascos que hacían nunca se acabaría la fresa. El dia siguiente fueron al estudio del noticiero, les dijeron que anunciarían de la mermelada. La anunciaron y esa mermelada estaba en todas las tiendas de el mundo, y les dijo algo, Donde había guerras comieran la mermelada y pararon las guerras. Los niños y la ninas que están super enfermos comieran esa mermelada y se curaron, a todo el mundo le paso algo hermoso. FIN Group B: First Place Carla Escribe Por Mason Lane Drummond Cada manana las 5:00 la mama de Carla se despertaba y tenia cuidado de no despertar a su pequeña hija. Se vestia con vestia con ropas viejas y llevaba sus cosas para un autobús sin ni siquiera comer su desayuno. Se iba a limpiar la casa de un autor hacendoso y con muchos privilegios. Trabaja ahí toda la mañana limpiando una gran porción de la mansión para una paga de 15dl al dia. Carla amaba a a su mama, y no entendia porque tenia que irse cada dia y dejar a su hija sola. Ella no entendia porque tenia que ir a la escuela con ropa fea y barata, cuando las otras ninas en su grado se ponían vestidos tan elegantes y bonitos. Una vez pregunto a su mama, pero lo único que la mujer cansada y con hambre le dijo fue: - “¡Hay Carla somos inmigrantes” y respiro profundamente - No lo vas a entener hija, es muy complicado. Como Carla solo tenia 6 anos no entendia la palabra inmigrantes a si que lo pensó mucho. Cuando tenia 8 anos decidio preguntar a su mama otra vez, esta vez su madre la hizo sentar en una silla para escuchar. -“Oh Carla, estoy muy triste” - “Porque, mama? Dijo Carla. - Porque deseo regresar a Mexico y deseo que tu papa estuviera con migo Su mama empezó a llorar. -Carlita en este lugar no somos importantes. Somos algo llamado inmigrantes. Y eso es malo. Carla no entendia pero desde ese momento decidio ayudar a su madre para toda la vida. Ya cuando estaba en quinto grado sabia lo que era una inmigrante estaba creciendo y aprendiendo varios idiomas ya comprendia lo que decía mama. Las ninas en la escuela no le trataban bien y era horrible, como la maestra decía que escribir era una buena forma de expresión y ella era muy buena escribiendo, empezó a escribir sobre su situación con sus compañeras. Elaboro en un cuento largo sobre unas brujas que eran ninas malas durante el dia. Le encantaba escribir y continuo escribiendo mas y mas. Un dia se cancelo la escuela de Carla y no podía estar en casa sola todo el dia, asi que se fue con su mama al trabajo. La casa era gigantesca. Y como no tenia nada que hacer fue a explorar para encontrar un lugar para escribir en paz. Muchas partes estaban cerradas, pero una estaba abierta. Con curiosidad, siguió adentro, un señor la veía con interés. - Porque estas aquí. - Mi mama trabaja aquí, respondo Carla. - ¿Qué tienes ahí? Le pregunto el señor. - Un cuento - - ¿escribes? - - si. - -Yo también. Puedo leer tu cuento, le pregunto el autor. Como ella no dijo NO, lo empezó a leer. Cuando termino el autor le miraba con sorpresa. -Lo has hecho muy bien. El le dijo. - Si?, respondio Carla -Debes terminar ese cuento. Desde ese momento, cambio la vida de Carla. La escritura la cambio, ella había hecho algo muy bien lo cual la motivo a creer que su vida era valiosa. Ella crecio a ser una mujer respetada y bonita, la escritura le ayudo a serlo Group B: Second Place The Starts in the Sky By Alexa Klumpen “No! No! don’t go please, don’t go! Francesca you don’t know these people, they could kill you they could lock you in a room with no food or wáter. I would die if you died.” Cried Francesca’s abuelo. “I know tata,” replied Francesca, “but I have to go, these are great new opportunities in the U.S. and I need to see my parents and my btother. It has been 10 years since I last saw them I miss them so much. I will miss you so much and I know what could happen on the way, but I have to go. The coyote is coming tomorrow at 6:00 a.m. I’ll have to be ready to go by then.” Wham! The door shut and Francesca’s abuelo walked out with tears in hs eyes. It was already 11:00 p.m. They both went to bed without saying another word to each other. She dreamt that night about the day her parents left with her older brother. She was only five years old and she cried and cried. Her father and mother had jobs in the US. They hadn’t taken Francesca because she was so young and the journey would be to harsh. Their plan was to send for her as son as she was old enough, Her pillow was wet for her tears when she woke up in the morning. Now, she is old enough to undertake the dangerous and scorching trip. Her parents had sent the money, $3,000, to pay the man who would guide her through the desert and across the border. Her grandfather was scared to send her and was going to miss her with all his heart. He disagreed with her parents about letting her do this journey on her own. She was ready to go. She was wearing the ring her mother had given her when she left and a bracelet her abuelo had made for her. When the coyote came to pick her up she was as ready as she thought she could be. The only thing that she carried was a backpack with tissue, a change of clothing, a few dollars, a baseball cap and a rosary form her best friend. She was also separately carrying a big bottle of frozen wáter and small one of wáter. She had sewn a larger amount of money into the hem of her jeans. When the coyote arrived she tore herself away from her abuelo and got into a van with no Windows. There were five other people in the truck when she got in and they picked up another four people on the way. They drove for what seemed like forever and when they finally stopped they were told to get out and go to the bathroom. The first truck drove off and left them standing there to wait for the next one which would take them to a place where they would have to sratr walking the rest of the way. Finally after waiting an hour the second truck came with people already on it. Francesca’s group was crammed into the truck. The truck smelt like pee and was really small. When Francesca’s group got on the truck everybody was asleep even thought it was around 2:00 p.m. They tried not to wake them but as son as the truck turned a corner everybody in it piled on top of each other. That drive took so long. About half way through they stopped for a bathroom break and stretched. Then they were shoved back into the truk and drove for so long again. When they finally stopped again it was already sunset and they were going to have to walk through the desert then sleep there and then walk farther. The coyote at that time told them to keep walking in the direction that he pointed and they would get to the border, there they would have to cross without being noticed. That was going to be the tricky bit. Then the truck door shut, the enginess turned on and the coyotes drove away leaving the travelers behind. They started walking in the direction that the coyote had pointed. They walked a long, long way until it had become too dark to see. They drew an arrow in the ground showing the direction that they have to be going in and then everybody lay down and went to bed. That night Francesca dreamt about seeing her parents and brother again and how wonderful it is going to be when she gets to them. She had a great night and woke up happy until she found that everybody had left her sleeping and the slight breeze had covered up the arrow on the ground too. Francesca freaked out and sat down to cry. She cried for about an hour and then go up and started walking in the direction she thought was the right way. She was already low on wáter, she had less tan half of the big bottle left. She wandered and wandered, but nothing changed. It was only dry and hot the whole time. When Francesca finally stopped to have a drink she accidentally knocked it over not realizing it untill all of it spilt out. She now had no more wáter and knew she needed to get somewhere and find more wáter otherwise she would die. She wandered the whole day without seeing anything but cactus and dry cracked ground. When it got dark she lay down and fell asleep from exhaustion. Waking up in the morning to a lizard crawling on top of her head, she shooed it away and made herself get up. She was already getting weak and did not want to go further but she knew she had to get going and find some wáter. It was so hot that dry. She walked the whole day stopping every 30 minutes. When it bécame night she sat down. She needed to keep herself alive. She was afraid, really, really afraid. Francesca dozed since she was so tried, but she Heard the coyotes howling in the distance. To get through the night Francesca started at all the stars in the sky. When she woke up she started walking, more stumbling. She couldn’t see properly or think propertly. It was all blurr for her. She walked a while until she sat down for a rest. Francesca kept passing out for a few minutes at a time but way too often. After passing out for around 10 minutes, she saw her parents in front of her. Francesca shouted out to them “ Mami? Papi? Is that you? Please help me I need you so much.” “We know,” replied her parents “That is why we came here. We love you more that anything in the world. Your dad and I so proud of you. We love you.” Francesca smiled really big, closed her eyes, and went to sleep for the last time. Group B: Third Place El Gusanito Gormito Habia una vez una granja, un gusanito llamado Gormito que vivía tan feliz y campante en un pequeño rincón del granero y compartia con otros gusanitos que eran sus amigos. Un dia gusanito Gormito les comento a sus amiguitos que era hora de partir, porque tenia que cumplir una gran misión, asi que, los demás gusanitos le preguntaron. ¿ Que misión es? Platicanos El gusanito Gormito les contesto Que todos los gusanitos en el mundo tienen que convertirse en bellas mariposas. Los gusanitos quedaron tan impresionados que empezaron a decirle al gusanito Gormito que ellos igual iban a ser hemosas mariposas ya que querían ver el hermoso paisaje que les rodeaba. Esa misma tarde el gusanito Gormito empezó a poner un poco de ramitas y hojitas para llevárselas al momento de partir; al dia siguiente el gusanito Gormito se depidio de todos sus amiguitos, miro a lo lejos un hermoso y frondoso árbol y les dijo a todos sus amigos…. Alla voy a cumplir un gran sueño. Todos sus amiguitos lo felicitaron porque Gormito era un gusanito muy sobresaliente. En su camino rumbo al frondoso árbol se encontró un grupo de gallinas que intentaron comérselo, ¡ah! Pero el gusanito Gormito era muy inteligente comenzó hablar con ella diciéndoles que no se lo comieran porque de lo contrario la gallina que se lo comiera se pondría gorda y fea y como en ese momento pasaron los gallos mas guapos, las gallinas no se lo comieron porque eran muy vanidosas. El gusanito Gormito siguió su camino al frondoso árbol y no tardo mucho en encontrarse al grupo de gallos que al igual que las gallinasse lo intentaron comer y nuevamente el gusanito Gormito convencio a los gallos de no comérselo porque eran igual de vanidosos que las gallinas, ya que el gusanito Gormito les comento que si se lo comían se pondrían gordos y feos y no tedrian pegue con las gallinas, asi que desistieron en su intento por comérselo. El gusanito Gormito ya no quería encontrarse ningún peligro asi es que vio a un grupo de conejos y les pregunto muy amablemente que si lo podían llevar al árbol y uno de ellos le contesto que si que hiba a ser un placer llevarlo al árbol ya que cerca del frondoso árbol había un huerto de zanahorias, por fin durante varios segundos saltando sobre el lomo del conejito llego al frondoso árbol Gormito se despidió y agradeció al conejito porque sin su ayuda no podría haber llegado. Cuando se bajo del lomo del conejito el gusanito Gormito se subio rápidamente a lo mas alto del árbol y ahí paso dia y noche, dia y noche hasta que un dia por la mañana una hermosa, hermosa mariposa salio y voló hasta donde vivian sus amiguitos y ahí uno de ellos lo vio y le pregunto… ¿Eres tu Gormito? Y el gusanito ahora mariposo le contesto – si soy yo estoy volando feliz. Y colorin colorado este cuento se acabado. Beauford Peever's Animal Family By Hector Curriel The story of my book started some four years ago, in a casual conversation with my wife about how sometimes members in our family have certain animal characteristics. It seemed to be so hilarious, and then I thought that it would be a good story for a children’s book. This is my first experience being author and an illustrator at the same time, and I am so grateful to have done this wonderful project. Beauford Peever’s Animal Family is a tale of a boy’s imagination, fueled by his love for animals, and a big discovery that will change the rest of his life. This ebook is suitable for children 4 years and up. Contains colorful illustrations and is great for the whole family. Available in a Spanish version also, as La Familia Animal de Beauford Peever, through Amazon.com. Here are some of the opening pages and illustrations: By Gloria “Cookie” Alcozer Thomas Her eyes became wider than a hoot owl’s when she saw Mama Bee waiting for her at the entrance of her house. “Hurry up, child! You’re slower than a turtle,” Mama Bee said, clapping her hands to speed Rose along. Then she snatched the baby right outta her arms and laid her on a massive big bed. Rose didn’t complain when that gray-haired ol’ woman took Cinnamon into her large hands. She knew, as big as Mama Bee was, she had a heart that was bigger still. Cinnamon slowly opened her tiny eyes, looked around the curious room, and could hear her mama talking with the strange-looking ol’ woman. But she didn’t understand a word they were saying. Bored, she yawned and closed her eyes again, falling right back to sleep. “But I can’t do that, Mama Bee!” Rose wailed after Mama Bee explained what was so important and what Rose needed to do. “What if the storm hurts my baby?” “Listen here, Rose, if this here is anythin’ like the last heat wave, then on the eighth day, the heavens are gonna open up and pour down rain so heavy it will wash away any evil that’s about. But iffin that don’t work, the skies will open up again and bring ’bout the devil’s storm, and there ain’t nothin’ on God’s green earth that can stop it! It will kill everythin’ in its path.” Mama Bee paused to catch her breath, dug her chin in so she could look Rose straight in the eye. “Child, evil is amongst us! “It pains me to say it, but it started on the day Cinnamon was born. Only Cinnamon can break the storm, and only she can save you and the farm. You put the baby’s cot right at the entrance of the house, and let Cinnamon do the rest.” Mama Bee explained intently, “She’s a storm-breaker, Rose. You’ll see. She’ll split the evil storm away from the house. You, Charlie, and Ol’ Man Howard need to take cover in the cellar ’til the storm is over.” Rose began to sob as she rocked herself back and forth. “Ol’ Man Howard will never let me do that! If he finds out we’ve been to see you…Charlie will lose his job! And there ain’t no other work out there for us, Mama Bee!” “Shush, child! Ol’ Man Howard will thank you for what you’ll have done. Now get goin’! Go get ready for the storm. I can feel the evil comin’.”  Gloria “Cookie” Alcozer Thomas was born in Des Plaines, Illinois. By the age of 12, her poetry had been published in Harvard University’s magazine and the same year earned her the title of best young poet of Chicago. Her recent book, Feeding My Children, (TMC Londo n, Ltd, 2012) is a collection of poems and short stories. At present a British citizen, she lives with her husband in Northamptonshire, England. For copies, visit www.cinnamonandthebatpeople.com or at Amazon. Guest Editorial By Angela Valenzuela and Clarissa Riojas of University of Texas at Austin

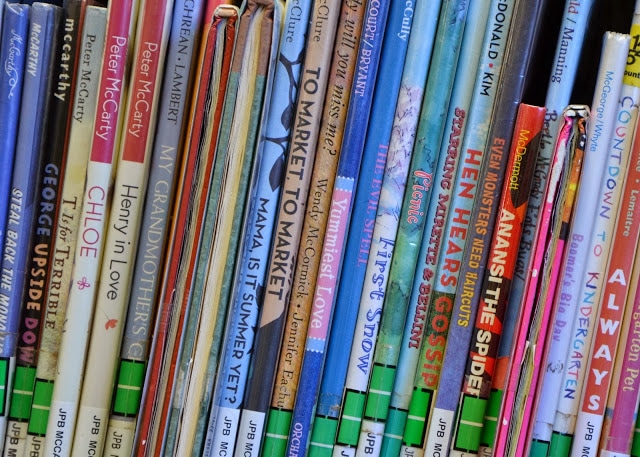

Despite flash flood warnings, an unusual spate of rain and high winds in a drought-devastated Central Texas, about 45 dedicated community activists, librarians, historians, archivists, scholars, and local leaders gathered in Austin on September 20, 2013, to address the significance of these figures. The consensus was a mixture of concern, outrage, and a commitment to take action. The timely publication of a Young Adult novel, Noldo and His Magical Scooter at the Battle of the Alamo and a visit by its author, Armando Rendón, sparked the event. Rendón is founder and editor of “Somos en Escrito Magazine”. The entire experience was otherworldly in that Rendón’s visit coincided in space and time with a conversation that has been building in the Austin community regarding the systemic unavailability of books that are not only written by, but that also have content that is relevant to the history and experiences of Chicana/os and Latina/os. Merging these agendas found expression in this historic gathering of local leaders that further sought direction from one of our own, Oralia Garza de Cortés, who is a leading voice for children’s literature and library and literacy services for Latino children and families at local, state, and national levels.  Oralia Garza de Cortés Oralia Garza de Cortés This was truly a shared community effort that involved the following co-sponsors: the Emma S. Barrientos Mexican American Cultural Center (also referred to as “the MACC”), Austin Parks and Recreation, Las Comadres and Friends National Latino Book, Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies; Benson Latin American Collection, the Center for Mexican American Studies and the Texas Center for Education Policy at the University of Texas at Austin, the National Latino/a Education Research and Policy Project, Modesta and José Treviño, and El Corazón De Tejas, the Central Texas Chapter of REFORMA, an affiliate of the American Library Association. REFORMA is a national association to promote library and information services for Latinos and the Spanish speaking. Serving as moderator, Dr. Angela Valenzuela from the University of Texas at Austin’s Texas Center for Education Policy, opened the event with general commentary on how the dearth of children’s books with content that is important to Latino/as intersects so powerfully with other advocacy areas that are also germane to the needs and experiences of our communities, including literacy, our literary heritage, intellectual traditions, archives, cultural preservation, and the arts. She urged the audience to consider ways that they can become advocates. Through his presentation, Rendón brilliantly and magically transported his eager audience to Noldo’s barrio in San Antonio, Texas’s West Side. The novel, set in the 1950’s, finds Noldo playing outdoors and witnessing sudden cloudbursts, lightning, and thunder that drenches the rutted street that is his playscape (caliche barrio). What follows next is Noldo’s own time travel story that transports him to 1836 to the Misión San Antonio de Valero, known today as “El Alamo,” where he befriends a young person his own age on the eve of this historic battle. After reading several passages from his novel, Rendón shared with us his own evolution as an editor-turned-children’s book writer. He mentioned how he came to realize through his research, looking through library catalogues, and talking to people around the country just how dire the situation is with regard to Latina/o children’s books. “There isn’t much available for young adults—certainly Chicanos and Latinos. And certainly not adventure stories, something that kids might read and see themselves in there, their story. And I think that’s what you’re talking about, that when young people read a book, they’re reading about themselves. When they pick up Noldo, I hope that young people will realize that this is their story and not just mine.” He mused about Noldo’s time travel and how his plans are to take him to the Mexican Revolution of 1910 where Noldo provides a personal, eye-witness account of the battle at Juárez from the safety of El Paso. Oralia Garza de Cortés’ stirring presentation addressed a range of issues associated with the systemic lack of access to Latina/o children's literature and how best to advocate. She noted that “Publishers must bear the brunt of this responsibility, although they’re not the sole culprits. The publishing industry is like a giant ship in that it has many moving parts. There are literary agents, editors, reviewers, selectors, librarians, book sellers, and book buyers,” she asserted. “Everyone plays a critical role in promoting, reviewing, and purchasing these books that have been vetted by a combined team of professional librarians to select the best of the best. Without the published books, there can be no selection,” she said. Oralia shared the shocking news that at this year’s Pura Belpré Award—one of three major awards given to Latino/a children’s book authors—the selection committee did not select books for special honors. “It was stunning to be in a room of 5,000 librarians and it’s like the Academy Awards when you’re in this room,” she said. “When they read the statement that said ‘no honor books for writers,’ there were gasps in the room.” She explained how this rare occurrence was the result of not having enough books to select from and how this speaks volumes about the lack of literature from which to select, as well as one committee’s insistence on quality. She further situated this crisis in the context of a 50 million and growing school-age, Latino population, noting that the limited number of published books—less than 200—is a travesty. “Que verguenza!” she exclaimed. What followed was a lively conversation on how to begin to change this with the multiple and varied strategies that can serve as guideposts for what many of us in Austin believe is an idea whose time has come. Archivist, scholar, and activist Martha Cotera launched the conversation with the following observation: “I think one of the issues is that as a community, we fail to serve on city boards and commissions. And I think that the local REFORMA chapter should definitely ensure that there’s always a member on the library commission. I did my time. I’m a founder of REFORMA National and I did eight years on the Austin Public Library Commission. . In those eight years,we did extensive evaluations and surveys on service to Hispanics. There is much service one can do. So if you are not serving on a board or commission, you cannot blame anybody for bad service.” Local labor leader and library activist, Teresa Perez-Wiseley, agreed that advocacy in small and large ways is a must. She shared that it should not be a difficult proposition getting these books into our children’s schools, but it is. Teresa suggested to the audience that to override the bureaucratic hurdles it is often best to simply purchase and donate Latina/o children’s books to our local school libraries. An audience member raised an issue mentioned by Garza de Cortés that many of the children’s books for Latina/os that she came across actually had damaging content. She asked whether there is any organization that sends out a list that says, “Do not buy this because this is not a culturally sensitive book?” None appears to exist. Another person situated this conversation in the context of the Austin Independent School District’s dual language programs saying, “All of our teachers are complaining that they still cannot find enough Spanish literature for our children.” She asked for direction not on just how to get more books in their hands, but ones with appropriate, “correctly translated” content. She underscored how a demand exists. “We just need to know how to get the books. Just as Teresa said, they’re looking at South America. They’re trying to get the books to the kids, but it’s hard.” Some discussion centered on how to become a Latina/o children’s book writer. Both Rendón and Garza de Cortés referred to the important, if complex, negotiation of two language systems that capture well the discourses, identities, and histories of our communities but also work politically to elevate us in the eyes of publishers beyond our more typical designation as “regional minorities” for a “regional market.” This is an antiquated mentality that needs to get challenged. Other issues that surfaced included a lack of Latina/o librarians or other committed individuals responsible for insuring that our library collections are sufficient, that is, the pipeline for careers in librarianship is fragile and should be strengthened. Aside from Cotera’s and Perez-Wiseley’s commentaries on assuming leadership positions locally and advocating singlehandedly, respectively, both Texas historian Dr. Emilio Zamora and Martha Cotera suggested workshops or a Saturday school for our community that could be held at the MACC. It could be a site for professional development workshops, as well as organized events around different kinds of writing like history or poetry that brings writers and community to spaces like these to address larger issues related to writing and publishing. The evening ended with a reception and book-signing event with multiple copies of Noldo finding their way into eager hands. The reception was rife with hope and expectation that we would reconvene soon to begin contemplating artist workshops, a Saturday school for Latina/o children, and a targeted strategy involving the City of Austin and Austin Public Libraries in order to begin to meet the demand that exists. We conclude with Rendón’s apt commentary on the task that lies before us: “Writing for children is a political act. More people realize that in our community. Look at the powerful people in this room. It’s amazing. I feel like a kid, you know, imagining how we can get this movement growing into something even bigger.” We feel like kids, too, Armando. You and Noldo are helping us to grasp our need to travel to the past in hopes for a brighter future. Gracias!

Clarissa Riojas, graduatingthis year from UT Austin with a B.A. in English Literature, Mexican American Studies, and a certification in Latino Education, Language, and Literacy under the Bridging Disciplines Program, is an intern with Dr. Valenzuela in the Texas Center for Education Policy. |

Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

Somos En Escrito: The Latino Literary Online Magazine

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

©Copyright 2022

RSS Feed

RSS Feed