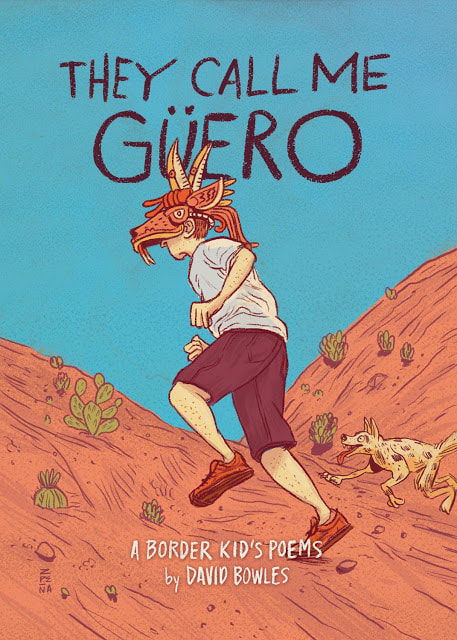

They call me guëro Border Kid It’s fun to be a border kid, to wake up early Saturdays and cross the bridge to Mexico with my dad. The town’s like a mirror twin of our own, with Spanish spoken everywhere just the same but English mostly missing till it pops up like grains of sugar on a chili pepper. We have breakfast in our favorite restorán. Dad sips café de olla while I drink chocolate— then we walk down uneven sidewalks, chatting with strangers and friends in both languages. Later we load our car with Mexican cokes and Joya, avocados and cheese, tasty reminders of ourroots. Waiting in line at the bridge, though, my smile fades. The border fence stands tall and ugly, invading the carrizo at the river’s edge. Dad sees me staring, puts his hand on my shoulder. “Don’t worry, m’ijo: “You’re a border kid, a foot on either bank. Your ancestors crossed this river a thousand times. No wall, no matter how tall, can stop yourheritage from flowing forever, like the Río Grande itself.” Borderlands Sixty miles wide on either side of the river, my people’s home stretches from gulf to mountain pass. These borderlands, strip of frontier, home of hardy plants. The thorn forest with its black willows, Texas ebony, mesquite, huisache and brasil. Transplanted fields of corn and onion, sorghum and sugarcane. Foreign orchards of ruby red grapefruit white with flowers. Native brush rainbow bright with purple sage, rock rose, manzanilla and hackberry fruit. Beyond its edges spreads the wild desert, harsh and lovely like a barrel cactus in sunny bloom. Checkpoint On our road trip to San Antonio for shopping and Six Flags, Dad slows the car as we approach the checkpoint, all those border patrol in their green uniforms, guns on their belts. Mom clutches los papeles—our passports, her green card. She’s from Mexico. A resident, not a citizen, by her own choice. At the checkpoint a giant German Shepherd sniffs the tires as the agents ask questions, inspect our trunk. My little brother squeezes my hand, afraid. My rebel sister nods and says her yessirs, but I can tell she’s mad, the way her eyes get. We’re innocent, sure, but our hearts beat fast. We’ve heard stories. Bad stories. A cold nod and we’re waved along, allowed to leave the borderlands— made a limbo by the uncaring laws of people a long way away who don’t know us, a quarantine zone between white and brown. I feel angry, just like my sister, but I hold it tight inside. We just don’t understand why we have to prove every time that we belong in our own country where ourmother gave birth to us. Dad, like he can feel the bad vibes coming from the back seat, tells us to chill. “It won’t always be like this,” he says, “but it’s up to us to make the change, especially los jóvenes, you and your friends. Eyes peeled. Stay frosty. Learn and teach the truth. Right now? What matters is San Antonio. We’ll take your mom shopping, go swimming in the Texas-shaped pool, and eat a big dinner at Tito’s. Order anything you want.” And he slides his favorite CD into the battered radio. Los Tigres del Norte start belting out “La Puerta Negra”-- “Pero ni la puerta ni cien candados van a poder detenerme.” Not the door. Not one hundred locks. Ah, my dad. He always knows the right song. Our House Our house wasn’t ready all at once. Our house took years to grow, like a Monterrey oak gone from acorn to tall and broad and shady tree. My parents saved for years, bought a nice lot on the edge of town, drew up the plans with Tío Mike. One year the family poured the foundation, then the next these concrete walls went up. Atlast my father built a sturdy roof, and in we moved, finishing it room by room, everyone lending a hand, every spare penny spent para hacernos un hogar-- a home that glows warm with love. Now it’s like a bit of our souls has fused with the block and wood. I can’t imagine life without this place— on these tiles I learned to walk. Here are my height marks, with fading dates, higher and higher. Oh, all the laughs and tears we’ve shared at that table! All the cool movies we’ve watched sitting on that couch! And here’s my room, filled with all my favorite stuff, sitting in the shade of the anacua tree I once helped to plant. A modest home, sure, but inside its cozy walls we celebrate all the riches that matter. Pulga Pantoum Mom and I love to go to the pulga, to get lost in the crowd that flows between all the busy stalls, drawn to colors, sounds, and smells. To get lost in the crowd. That flows from our instincts, I bet. Humans are drawn to colors, sounds, and smells like a swarm of bees to blooming flowers. From our instincts, I bet humans are happiest together. Bulging bags in hand, like a swarm of bees to blooming flowers, people meet for friendly haggling. Happiest together, bulging bags in hand— Mom and I love to go to the pulga! People meet for friendly haggling between all the busy stalls. Fingers and Keys My mom’s the organist for our parish-- One of the last, she says. When I was little, she taught me to play on a worn-out old upright that stands in a corner of our dining room, holding up family photos. Even though I’m twelve now, when I sit down to practice, laying my hands upon the keys, I sometimes feel her fingers on mine light as feathers but guiding me all the same. Lullaby Like lots of border kids, my first song was a lullaby that my abuela sang to warn me and to mystify. My mom says when I got home, smiling without teeth, she took me in her arms and serenaded me-- Duérmete mi niño Go to sleep, my baby duérmeteme ya sleep for me right now porque viene el Cucu to keep Cucu from coming y te comerá. and swallowing you down. Y si no te come, And if he doesn’t eat you él te llevará he’ll take you far from me hasta su casita to his little cabin que en el monte está. that sits amid the trees. So I learned the dangers of this crazy, mixed-up place— there are monsters lurking, but family lore can keep you safe. Learning to Read When I was a little kid, my abuela Mimi would ease down into her old, creaky rocking chair to tell my cousins and me such spine-tingling tales as ever a pingo fronterizo, crazy for cucuys, could hope to hear. I always had questions at the end of Mimi’s stories. What was the little boy’s name? What did his parents do when they found him missing from his room? Is there a special police squad that tracks down monster hands and witch owls and sobbing spirits in order to save the boys and girls that they’ve stolen? “No sé, m’ijo. The story just ends. Happened once upon a time. Nobody knows.” But I didn’t get it. I was so literal. I believed every story she told was true. So I kept asking my questions, guessing at answers till she broke down at last and told me the greatest truth: “You have to learn to read, Güerito. You will only find what you seek in the pages of books.” So I began to bug my mom to teach me to read till she did. I was barely five at the time. First day of kinder arrived, and I was so excited at all the books my sister said were waiting on the shelves for me. But then the teacher started drawing the letter “A” on the board, and I soon got it— none of the other kids could read. She was going to teach us the alphabet one letter per day! Not me! No way! I dropped out of kindergarten, little rebel that I was. Instead, my mom took me to the public library every day, all year long. I read book after book after book delighting in the new tales, the strange and mysterious places. And when first grade rolled around (not optional like kinder), the school was so amazed at my skill they put me in a third-grade reading class! I got picked on, sure, but I was pretty proud and didn’t care when kids called me nerd. The school counselor told my folks I can already read at college level! And I’ve found lots of answers, but also many new questions. Of course I pass all the state tests with super high scores. Learning in class is easy for me. Dad says all those books rewired my brain, got me ready for study. Just think-- I owe it all to those stories my abuelita used to tell us sitting in her rocking chair as we shivered and thrilled. Even then, words were burrowing into my brain and waiting, like larvae in a chrysalis, to unfold their paper wings and take me flying into the future.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

Somos En Escrito: The Latino Literary Online Magazine

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

©Copyright 2022

RSS Feed

RSS Feed