|

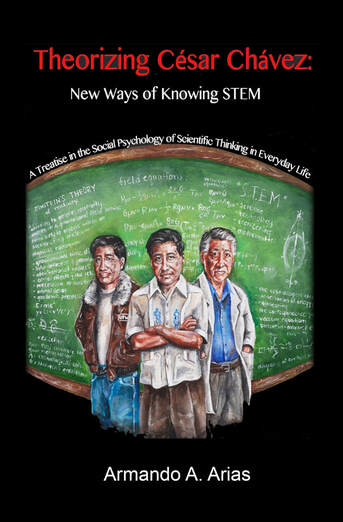

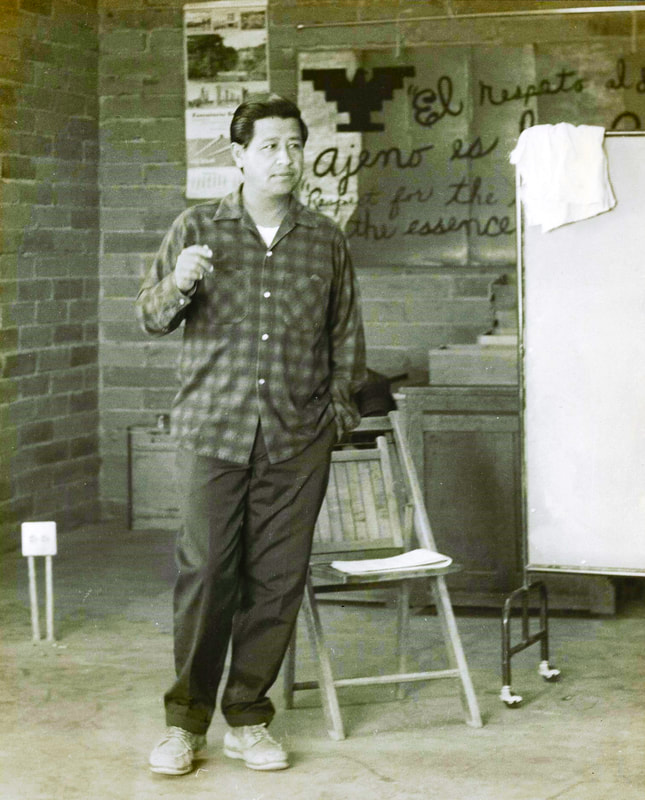

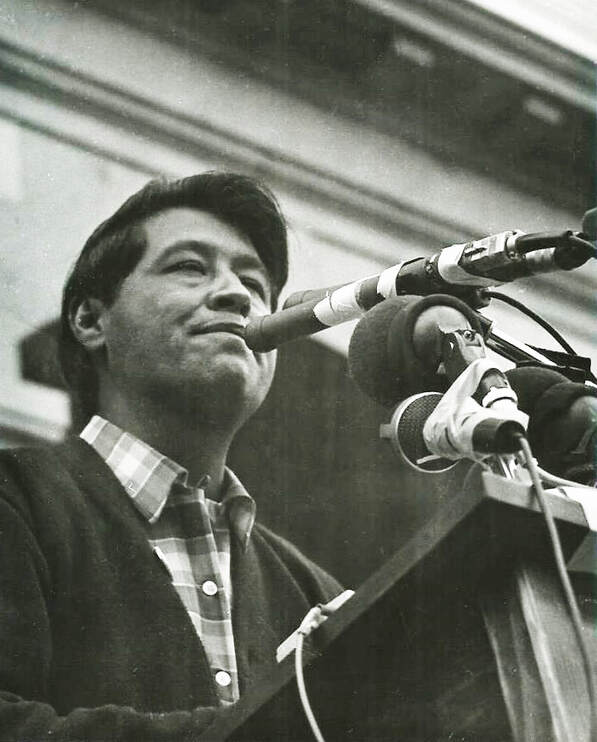

The Somos en escrito Literary Foundation Press is privileged on the occasion of the birthday of César Chávez on March 31st of 2020 to mark the event by introducing the following publication in his honor. Theorizing César Chávez New Ways of Knowing STEM A Treatise in the Social Psychology of Scientific Thinking in Everyday Life A social psychological treatise by Dr. Armando A. Arias, which offers a much-needed review of STEM studies: science, technology, engineering and mathematics, through the eyes of a theoretical César Chávez, renowned labor leader, to re-locate the focus of STEM on the people, that is, on the Chicano and Latino students being recruited into these fields of study. Arias, a social psychologist by trade, is a professor and founding faculty member in the division of Social and Behavioral Sciences and Global Studies at CSU Monterey Bay. Copies are available in print and ebook formats from online booksellers. Ask your local bookstore for copies and to stock it. See more at our Bookstore / Librería or the book's page to learn more. Paperback https://www.amazon.com/dp/B086FZTPSG Kindle: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B086H4SDRN Theorizing César Chávez / New Ways of Knowing STEM / A Treatise in the Social Psychology of Scientific Thinking in Everyday Life is a publication of the Somos en escrito Literary Foundation Press, an enterprise of the Somos en escrito Literary Foundation, a 501(c)(3) tax exempt organization under the U.S. tax code. For more information, contact Armando Rendón, at [email protected]. Theorizing Armando Arias’ book:Theorizing César Chávez Book Review of Theorizing César Chávez New Ways of Knowing STEM A Treatise in the Social Psychology of Scientific Thinking in Everyday Life By Robert A. DeVillar To what degree are iconic figures, even those whose characters have been transformed to virtual mythological status, relevant in informing and guiding policies and practices in areas that are deemed to be officially critical to our nation’s future, both domestically and as a global leader? In his book, Theorizing César Chávez: New Ways of Knowing STEM, Armando A. Arias has tackled this intriguing question through creatively and imaginatively overlaying the ideas, thoughts, values, beliefs and actions of César Chávez, world-renowned as leader of the California-based United Farm Workers (UFW), upon the disciplines of science, technology, engineering, and math, known collectively in the United States as STEM.[i] The purpose of this overlay—used here in its computing sense of “transferring one block of program code or other into internal memory, replacing what is already stored”[ii] — is to effectively produce a framework to transform the manner in which STEM disciplines are pedagogically taught and professionally applied. Two corollary questions immediately spring to mind. The first being what has been and continues to be a collective problem or set of problems in the current STEM framework that would demand a new framework? The second being what qualities—inherent, those acquired informally or learned formally through direct or indirect experience, and refined through his keen mental acuity—characterized César Chávez to such an exceptional extent that he, as the embodiment of these qualities, could serve as a model for constructing and implementing the proposed innovative STEM framework? In response to the first question, STEM requires a paradigmatic shift from its targeted focus on curricula, methods and products to focusing on the people, which requires not only effectively recruiting, retaining and educating students and hiring professionals from diverse and underrepresented backgrounds as scientists and associated roles, but also effectively addressing needs of the people of our nation, and those on earth. Integral to this new focus is that STEM’s fundamental purpose is to research, discover and develop processes and products that serve the sustainability and regenerative needs of our earth (our natural resources) and the general well-being of its people across the dimensions—social, economic, political, cultural—of our individual and connected lives. In support of the second question, Arias highlights the works of more than 50 innovative figures from diverse cultures, from distinct historical periods, and from the present. This array of thought-provoking, paradigm-shifting or paradigm-disrupting philosophers, social scientists, scientists, linguists, community organizers, dramatists, politicians, novelists and investigative reporters[iii] connects aspects of their thoughts and paradigms to the development, both self- and leadership-, of César Chávez and his actions. César thoughts, ideas, and actions blend harmoniously with the respective thoughts, ideas and actions of the figures, and at the same time César’s self is disrupted and challenged by this harmony. That disruption motivates him toward further self-reflection, study and action in the endless pursuit of development of his Self and refinement of his role as a leader whose ultimate goal is to improve the conditions of his people—and, ultimately, we are all his people. The integration and dialectical interaction of (a) the need for a paradigm shift in STEM and STEM-associated areas (to include farm worker conditions and exploitive models and practices in general) and (b) the confluence of enlightened knowledge consistently flowing through César formed an internal metaphorical infinite loop that was at once recursive and regenerative. The portrayal of César Chávez in Arias’ work is also intriguing, as his biographical presence extends beyond his death in 1993 and some of the interactions in which he was described as taking part were fictionalized. These seemingly contradictory and non-logical devices are a purposeful part of Arias’ work and are at the heart of the search for truth—namely, that it includes the subjective world as well as the objective. To put it more strongly, and this is well known both in the sciences and the arts: “Absolute truth is fiction.” The scientific method is fundamental to STEM disciplines, and was adopted, although not exclusively or in whole, early on within the social sciences. Yet, the scientific method is itself neither immune to working with the unknown— for example, that which has to be imagined by way of hypotheses or approximations by way of probabilities—nor to turning a blind eye to purposes for which particular research or the selective or restrictive application of research outcomes are intended. In the case of hypotheses and probabilities, the vagueness or impreciseness of anticipated outcomes are qualities that may be viewed, respectively, as purposeful extensions of facts into the unknown and faith—the world of conjecture, of fictionality, so to speak. And, it is here that we ascertain the critical difference between truth and absolute truth. The former is ideally accessible and demonstrable through sound application of the scientific method within the larger context that embodies and adheres to the objective operating assumptions of the meta-discipline known as science; the latter, by fiction. The purposeful use of the scientific method to discover, produce and apply results to favor or prejudice a particular group over another or others does not conform to the definition of science in any of its diverse forms. Yet, from the 1600s to 1943, nearly the end of WWII, scientific racism was integrated into the operating paradigm of science and the scientific method was used to sustain its prejudicial and racist premises built on Aryan-Teutonic-Celtic myths. In the United States, scientific racism ran parallel with its societal racism until its association with the policies and practices of Nazi Germany in the 1930s and the subsequent WWII pseudo-scientific race-based atrocities by Germany in Europe and by Italy in Africa made the comparison of US scientific racism on the home front to the scientific racism of the very enemies we were fighting politically untenable. Our legally-instituted societal racism trailed behind distancing ourselves from scientific racism by two decades, in 1964 and 1965, even though the former process began seriously, but in violent and vitriolic fits and starts, by way of the Brown v Board of Education of Topeka decisions (I and II) of the Supreme Court in 1954 and 1955. Although César Chávez was born in Arizona on March 31, 1927, he was intimately familiar with this type of context, as he attended scores of public schools in Arizona and California where the vast majority was segregated by fiat and would remain so until court decisions in 1950 in Arizona and 1946-1947 in California made the purposeful practice of segregation of Mexican-origin students illegal. The schooling contexts that César was subjected to are important to illustrate, as they were the early formal socialization experiences that informed his thoughts, ideas, and actions throughout his life. Arias convincingly illustrates and integrates the effects of schooling, family life and its conditions, and field work experiences on the self- and leadership-development of César, and the result of this development on his perspective of STEM as it is and how it should be. César’s unique character was shaped in fundamental ways by the compendium of his life experiences. The varied and complex external aspects and tensions associated with his character development included (a) his formal socialization through schooling, which ended in the eighth grade; (b) his immediate family context characterized by love, a pattern of economically-driven, forced mobility, and sustained economic hardship; and (c) his full-time work in the agricultural fields from the time he was 15 years old. The manner in which César observed, sensed, struggled with, thought about, and ultimately internalized his external experiences resulted in the development of his full character. Interestingly, by his own self-definition and definition of the self, his full character was itself in a constant dialectical state of self-questioning while concurrently fulfilling his role as a leader, working tirelessly to change the unjust working and living conditions of workers’ and families’ lives though his role as activist leader and simultaneously controversial and popular spokesperson on the local and global stages. The compendium of César’s early life experiences, coupled with his constant dialectical state, resulted, as Arias reveals, in yet another, unpredictable quality in his already unique character: the ability (a) to see, relationally, the known and unknown relative to a particular phenomenon within a particular context (that is, to observe the “here and now” and envision the future in relationship to it); (b) to think and speak about the elements within a particular context in the present and how they, if left in their present state or manipulated, would relate to different levels of current versus envisioned future outcomes; (c) to establish procedural ways of conducting activities such that the future outcomes could come to pass or observe conditions that thwarted the envisioned future outcomes to come to pass; (d) to follow the procedures and determine the extent to which the outcomes were successful for the specific context and its applicability to expanded contexts; (e) to move on to the next issue at hand, usually within the same problem-laden context, and approach it with the same logic and thoroughness in order to significantly effect a transformation from a current state of conditions needing change to the envisioned desired state of conditions. This ability and skill set sprang from such everyday home and school occurrences he observed or directly engaged in, such as making innovations to tortillas so they, once frozen, could be reheated without becoming brittle and cracking, or churning cream and producing, miraculously, butter—which also had a positive effect on his status among his classmates. In other words, César’s mind had developed and internalized, and was able to naturally and seamlessly apply the principles of the scientific method—from statement of the problem to hypothesis formation to design and implementation to analysis and interpretation and to recommendations for further related action. César applied the scientific method within his everyday external activities as he engaged simultaneously in his self-development process, knowing that even as the method itself was being applied, it was also in a constant state of refinement. And he undertook all this intense application, learning, refinement, and leadership, without sacrificing his already uniquely strong individual and social resolve, charisma, humility, moral virtue, accessibility, graciousness, and ability to communicate with his people locally and across the globe, be they field workers, scientists, philosophers, artists, presidents, media representatives, academicians, the Pope, or whoever it may be. But, as Arias illustrates throughout his book, César’s principles of the scientific method were bound within the larger and inviolate casing of social justice such that science would always serve the people by improving their living and working conditions. This paradigm of science, the scientific method, and scientific practice differs substantially, as we have seen, from traditional science serving those who use its discoveries and products to exclude, exploit, control or destroy others, or to exploit and manipulate through genetic alternation or other means Earth’s natural resources and living organisms. César’s Science is one, and can only be one, with a universal social conscience, commitment and common goal to (a) improve the living and working lives of all people, (b) sustain and regenerate the natural resources on earth, and (c) protect the environment—to include discovered past or present life forms--of planets and space beyond Earth. A Science that will universally commit to and focus on the health and well-being of Earth, its inhabitants and its resources. If we had in the US the requisite sensibilities and cultural inclusivity, which we have yet to generally display much less internalize as a value or practice, this transformative vision and approach for Science can and should be integrated within the STEM curricula along with, almost by definition, the concomitant focus and means to recruit and retain underrepresented students. Arias provides intellectual evidence that César saw this need early on, as most fair-minded people would now, and would remain in solid agreement with the logic and justice of this new STEM-related strategy and the corollary need to establish and implement concrete tactics to achieve the recruitment and retention goal. This way of thinking and acting clearly and strongly aligns itself with the guiding adage that Arias’ César never tired of saying to himself and others: “It’s about the people.” Furthermore, César would always contextualize the adage; thus, he would actually say: “It’s not about STEM; it’s about the people.” Arias probes further into the mind of César to semantically enrich the already-powerful “people” by adding specificity to it. He does so through the concept of culture and its multifaceted yet flawed relationship to critical, long-term, unresolved issues, such as worker exploitation, segregation and social injustice in the US, that prevent the people, in its inclusive sense, from sharing equally in opportunities to develop and prosper. The role of science plays a fundamental role in our culture as it is, can be, and has been, used in ways that sustain inequitable practices rather than to transform US culture to reflect and live its foundational principles through a relentless, yet shared, drive toward equity. Equity is defined here as being a function of three essential, interrelated elements: access, participation, and benefit.v In the immediate contextualized sense of the farmworkers’ continuing struggle for equity, this meant and means access to dialoguing within authentic communicative contexts, characterized by mutual respect, with farm owners and other influencers of policies and practices engaged in the issue in order to negotiate and achieve shared meaning to improve the working and living conditions of farmworkers in ways that are sustainably equitable. Arias’ demonstration that César would extend this same need to address issues of equity within the socio-academic contexts of STEM and science is threaded throughout the book and is effective in illustrating the necessity to tackle multiple major fronts of the same problem simultaneously. At the same time, Arias shows César to be aware of how nefariously effective the cultural inequity model is on targeted major segments of the populous—that is, those groups (and the individuals within them) who are subject to social control that creates dependency rather than to social liberty that creates freedom within our work fields, schools and homes, and other domains characterizing our national context. The need to identify one’s own group dependency and ways to extricate the group from it, while simultaneously working to socially engineer the movement toward freedom in the critical domains of work, school and home, are solidly present in Theorizing César Chávez. The array of historical and contemporary figures whose thoughts and actions Arias integrates into this work, as they influenced or paralleled César’s life and thought, and therefore his leadership actions and self-development, credibly and dexterously supports the uniqueness and strength of César’s character and values and their relevance to developing and implementing the transformative people-driven (rather than discipline- or problem-driven) framework within which STEM and science must operate to achieve its potential and goals.

The main reason we have not resolved this issue is a cultural one: the US survival model was meant for a particular group—white, male and landowning—and the model, which contained a fundamental racist value in its survival code, could accommodate those who were considered white.” This was far from scientific, but science still supported it, as mentioned above. Thus, we need workers in the fields but we don’t need to pay them fairly, or tend to their health needs, or concern ourselves about their mobility and how that forced phenomenon affects their children’s schooling or their families’ living conditions, or how long the hours they work, the tools they use, or pesticides they absorb through mere breathing or touching, affect their health and mortality, and so on. They are not perceived as being part of our core culture, our core cultural group. Yet, the saving grace, literally, in our nation’s character—as opposed to cultural character—relates to the universal rhetoric our founding documents guarantee to all Americans with respect to rights, responsibilities and freedoms, and that rhetoric took on a life of its own from Day 1 of our nation. Thus, we have fought since the inception of our nation and continue to do so to this day and foreseeable future to transform into general and equitable practice the legally attained rights, which should have been granted and adhered to in the first place, and those human rights issues we have yet to resolve. Arias has penetrated the mind and heart of César, as he interacted with others of all ilks and in diverse contexts, as well as in solitude, to bring to the surface César’s dialectical relationship with his highly complex, constructed social and individual reality, and how that process informed his every thought, idea, and action, as a human being and leader. Arias demonstrates masterfully that the set of values undergirding César’s thought processes and ways of seeing himself and his world and that of others remains a valid, supportive, creative and effective way of establishing frameworks that succeed, first at the human level, and concomitantly, at the issue level. Transvaluation—that is, effectively transforming, say, a core cultural value prizing racism to a core cultural value of prizing unity, as in e pluribus unum—is itself at the core of César’s belief system, work ethic and leadership. This was true in all walks and facets of his life, including the fields where workers toil, laboratories where scientists test and produce, and schools where students learn. Arias has produced a creative, challenging and convincing narrative case that is always intellectually and experientially broad in scope and, in particular sections, thoroughly fine-grained. In Theorizing César Chávez: New Ways of Knowing STEM, Arias has provided imaginative and critical insights into understanding that César’s values and way of seeing, reflecting and interacting with the world are key to the continued healthy development, sustainability and regenerative essence of our world and of people, both within our nation and our world. Moreover, the integration of his values, observing, thinking and acting combine to steer us—in work, school, home and community contexts—in an inclusive trajectory that ensures that quality access, meaningful participation and sustained benefit are enjoyed by all. As always, there have always been two sides to our nation’s coin, which in keeping with the scenarios presented in the Arias’ volume can be metaphorically alluded to as (a) staying the course represented by evermore scientifically effective ways of applying pesticides and producing hard-skinned square tomatoes; or (b) transforming the current STEM curricula paradigm to produce scientists (e.g., social, mathematical, biological and physical) through effective, equitable student recruitment and retention, and the development of their creative and problem-solving learning potential through teaching that is at once flexible and sensitive to what students bring to class from their context. Based on the evidence and insights provided by Arias, there is no need to flip the coin and take chances. My vote is to choose transformation. _____________ [i] In the early 1990s, the acronym STEM was used in programs targeting talented students from underrepresented groups by Charles Vela, founder and director of the Center for the Advancement of Hispanics in Science and Engineering Education (CAHSEE), and introduced through him to the National Science Foundation (NSF), which later adopted the term. [ii] Lexico.com. Retrieved September 9, 2019. [iii] The categories are not mutually exclusive; therefore, one or more of the more than 50 individuals cited may be identified as belonging to more than one category. [iv] Due to the complexity of everyday parlance in the US, this last rather convolutedly expressed group-identity qualifier mentioned above attempts to include those who identify generically as Chicanos, Hispanics, Latinos, Latin@, Latinx, Mexican, Mexican American, Spanish, Spanish American, Caribbean, Central American, or, more specifically, as Mexico and Spain are already included above, any of the 15 other Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America and 1 in Africa, or any combination of these. [v] DeVillar (1986, 1998); DeVillar & Faltis (1987, 1991, 1994); DeVillar & Jiang (2011).  Robert DeVillar, a native of San Antonio, Texas, has written and published academically for decades, but only recently began writing memoirs, covering his teen years in Spain and then Mexico, where he earned a dual degree in Latin American Studies and Social Sciences at the Universidad de las Américas near Mexico City. While seeking a degree in Mexican American Graduate Studies at San Jose State University (1973-75), he worked with Dr. Ernesto Galarza as coordinator of the Bilingual-Bicultural Studio/Laboratory (1972-1974) and Economic and Social Opportunities, Inc. He has traveled widely, engaged in private sector corporate affairs, but returned to complete a doctorate at Stanford University in 1985-87.

0 Comments

|

Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed