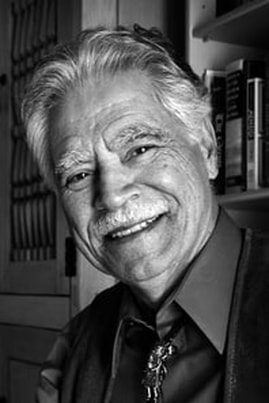

Rudolfo Anaya, pioneer Chicano writer, left us, Sunday, June 28, 2020  The entirety of Somos en escrito's literary family is saddened to hear of Rudolfo Anaya's passing. Not only has he brought joy and representation in literature and influenced us all, he unveiled the very presence of a Chicano literature to the world. His influence, artistry and authentic representation can't be understated. With Bless Me Ultima, he brought to the fore the internal struggles among Mexican Americans with the question of identity, the struggle in coalescing our indigenous, hispano and American worldviews, as well as honoring the place and times of rural New Mexico after World War II. In remembrance, we run a review published in Somos en escrito Magazine on July 20, 2013 by Adelina Ortiz de Hill, with Jaima Chevalier, both of New Mexican heritage, of Anaya's The Old Man's Love Story. The book is remarkable for its blending of the human values of love and death with the natural realities of heritage and human struggle. Review of The Old Man's Love Story: author, Rudolfo Anaya The Old Man's Love Story begins with the title character's loss of a partner, companion and lover in a poignant farewell at the dying woman's bedside, but the end of their life together brings forth a long dance between reality and conversations with a spirit. The opening sentence: "There was an old man who dwelt in the land of New Mexico, and he lost his wife" suggests a place where tradition and culture will play a key role in the story. By depicting how New Mexico's unique blend of Spanish Colonial, Native American, and Mexican history are melded together over the centuries, Anaya deftly weaves these legendary narratives into a study of death unfurled across a spiritual landscape through which Anaya offers the reader a lens with which to see life, love and loss. As the old man begins a dance between reality and conversations with a spirit, a photograph becomes a point of reference by which memories take on significance for his thesis. On page 17, Anaya refers to "Love, grief and memory. The sad, symbolic world of three, the old man's trinity." Thus begins the old man's interchange with the dead, and when he kisses the image, it is with an urgency borne of the need to recall her spirit. Rather than relying on the tired concepts of denial, anger and gradual acceptance, Anaya forges new territory in describing how the New Mexican experience brings geography and history into the survivor's experience of death. The role of geography and the pull of place factor heavily into his storytelling and remove it from the ordinary. Anaya's poetic descriptions of huge cloud formations dwarfing the terrain below, sunsets captured by the mountains, and huge and unearthly moonscapes create an intensely beautiful backdrop for a story that is simultaneously ripe with the past and vividly in the present. Into this magically spiritual landscape, Anaya draws the reader into the many directions the story wanders. On page 54, he describes a Native American symbol that reiterates the multifaceted New Mexican approach to the world: "The four sacred directions were intrinsic to the worldview of many Native American communities. The emblem on the New Mexico flag was the Zia symbol, a bright sun with lines radiating out in the four directions." This approach is intrinsic to Anaya's world view and views about death. His descriptions of Albuquerque's Sandia Mountains, vast thunderclouds, and gardens, create an extraordinary landscape through which the title character moves. This old man is not any ordinary old person. He is an educated man with profound memories of the literary journeys he has taken. He has also travelled the world, but is nonetheless at a loss to make these memories sustain him through the loneliness and sense of loss that overwhelms him when he loses his partner. On page six, the character asks himself: "What would he learn from his journey into the world of spirits? What illuminations might ease the pain in his soul? His search would parallel her journey, and at some point in infinity the two must meet… He would find her." For all his knowledge, he must still learn how to suffer through his loss, and his quest to find his lost partner creates parallel journeys. At the end of the book, the reader can believe that the old man's woman comes for him, and their transcendence to a world inhabited by cloud people traces back to the evocative New Mexico skies that Anaya has drawn. As Anaya traverses the stages of death in novel ways that allow the reader to discover new insights into when and where renewal will be found, he offers wisdom about the nature of the most profound loss humans experience. Anaya employs the use of internal dialogue that portrays the old man's religious beliefs, his reliving of history. The on-going dialogue with a life-affirming spirit is not a straight trajectory to a happy ending. The journey often reverts to loneliness and depression. Anaya depicts the old man's experiences at a senior center, with road rage, and a love affair. If a survivor is detached from his own roots, the experience of grieving makes the world limited but freed from these confines, grieving in the spirit world is limitless and a safe place to communicate about the eternal questions. Anaya portrays the state of New Mexico as a land of contrast, both in its dramatic physical features and in its mix of cultural traditions. The cultural mix surrounding mourning conjures images of times past, such as the Day of the Dead celebrations that meant taking a picnic to the cemetery for a day cleaning family graves. In traditional villages, honoring the dead meant holding a velorio (the form of wake traditional to many Spanish cultures) that pulled all parts of the community together, and ritualized memories of the dearly departed were a vital part of everyday life. A loss experience by one person is a loss that belonged to everyone. So, in this sense, death is alive in New Mexico as nowhere else. Although the traditions are slowly dissolving, traces of them are literally carved into the bluffs and mesas, where crosses and Marian shrines stand as signposts to memory. In New Mexico, grieving families place roadside descansos (shrines or crosses marking the place where traffic deaths took place) alongside highways and byways. These reminders of tragedy mark not only place, but stand as signposts to the past, a time when coffins were hand carried in procession from house to churchyard. Resting spots were marked along the way, and there was a community understanding that all grief was shared, no one suffered loss alone. The iconic image of the skeleton Grim Reaper, driving an empty carreta (carriage) evokes the dreaded image of the dead piled up to be carried away, and this reminder drives the living to comfort each other in communal ways as only social contact can provide. Thus, these little practices of a culture, showing how death is dealt with, are a microcosm of the bigger picture. In impoverished times, death looms larger, in a way, given the higher incidence of death due to socioeconomic imbalance. The significance of sharing loss together as a community crosses the entire spectrum from the youngest to the oldest—a time when friends and family meant profound ritual and not a cell phone network. These rituals then ingrained cultural rite of passage with baptisms, communions, and weddings marking steps along the way to our ultimate destination. In the chapter on" letting go" on page 127, the old man asks: "Is that all that's left in the end, photographs? The home we built. Every piece of furniture, books, her voice lingering here and there, favorite foods, friends—Is everything fading?" By coming to terms with being among the living, the old man struggles with insights into his own spiritual beliefs in the classic “two steps forward and one step back” process, that of surrendering to the way of all things. His on-going dialogue with a life-affirming spirit has frequent reversions to loneliness and depression, and railing against acceptance. American cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead referred to two islands, one of the living and one of the dead and love as the bridge. This bridge-world is Anaya's territory, one that he deftly maps, capturing the essence of the hispano-indio experience where myths and mystery are part and parcel of the terrain, as well as ultimate necessities for the grieving process to conclude. Anaya lost his wife Patricia in 2010. This book captures the essence of the hispano experience of New Mexico, and it solidifies Rudolfo Anaya's reputation as the quintessential author in this genre. The Old Man's Love Story is available through University of Oklahoma Press. A chapter extract is available in “Somos en escrito”; look for the big red rose or type in the title in the search box. The movie version of his classic novel, Bless Me, Ultima premiered earlier this year.  Adelina Ortiz de Hill, MSW, has published works across a broad range of topics, including social gerontology research that she conducted about Spanish-speaking populations of Michigan. She has presented seminars on death and dying around the country, including her testimony in 1974 to a congressional sub-committee about homeless elderly. She helped found the website: www.vocesdesantafe.org, an interactive internet repository for area history, as recounted through the diverse voices of the people of Santa Fe and surrounding environs. Jaima Chevalier assisted in preparing the book review; she has authored La Conquistadora/Unveiling the History of Santa Fe's Six Hundred Year Old Religious Icon.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed