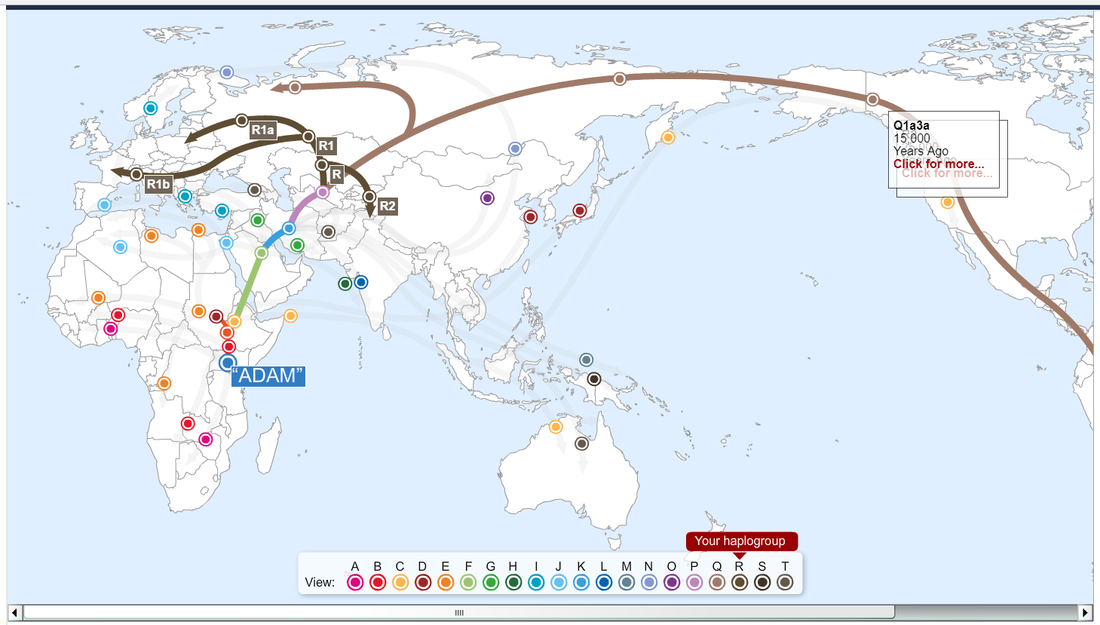

Chicano Confidential My nephews have a rock-and-roll band (Chicano ska) and recently they invited me to hear their new song, “I Don’t Speak No Spanish," that they sang completely in Spanish. I was immediately reminded of my cousin Avelino who years ago (while we were children) used to sing every single Beatle song in English; thing is, he didn’t speak English. Concomitantly in my capacity as the founder of the Salinas Valley Mariachi Conference and Festival, I brought a mariachi from Japan that wowed the primarily Mexican audience when the curtain opened. The Japanese Mariachis could not speak Spanish or English, but sang beautifully from the heart in Spanish. These are but a few concrete examples that cause us to temporarily do what Carlos Castañeda used to call, “Stopping the world!” Castañeda’s paradigm for looking out at the world was to “bracket” situations, “stop them,” and provide detailed analysis to the situation at hand (see Journey to Ixtlan: A Yaqui Way of Knowing). When we are caught off-guard by such experiences, when we temporarily “Stop the world!” as Carlos puts it, and examine social situations at the micro level, we experience a cognitive shift in our assumptions. Even so, I have to ask “What is the real message behind my nephew’s song?” or “What is it about the contradictions in their mixed message?” And why did they make it a point to bring it to my attention? These are young boys whose grandfather was a radical Chicano activist and whose father was a Mexican-American turned Hispanic. They are more than aware of their would-be Chicanismo yet prefer to refer to themselves as “multiracial millennials” and are quite comfortable with that label, just as they are comfortable with the results their father received from FamilyTreeDNA.com, which places his DNA mostly in Western Europe far from Aztlan. For the purposes of this discussion, we will use the term “Latino” to refer to individuals who refer to themselves as Hispanics, Mexican-Americans, Chicanos and/or Spanish. What makes a Latino a Latino (genetically speaking)?" has been recently complicated by the growth of the consumer genetic ancestry testing industry, such as FamilyTreeDNA.com, Ancestry.com, etc. When one is even more specific and asks “What makes a Mexican a Mexican?” or “What makes a Spaniard a Spaniard?” again, genetically speaking the realities of any response is even more complex. For many years, scientists, social and behavioral scientists, and anthropologists have known that the short answer to this question is that, "Being Mexican or Spanish means being multiracial." But that is also true for the majority of humans (whether they personally believe so or not). Humans have always migrated and intermarried. By the end of the first Human Genome Project (2003) and as a result of the popularity of the genetic ancestry testing these as well as other related tests have influenced many DNA test consumers to reassess their identity. How individuals interpret and use genetic test results to affirm or reconstruct their identities varies widely and is an excellent topic of social inquiry. Genome sequencing allows scientists to isolate the DNA of an individual person and identify different codes. A byproduct of this research is the ability to match the physical DNA (materials or the stuff one is actually made up of) to a geographic place—this is what gave birth to the thinking surrounding the consumer ancestry and genetic research industries. My theory is that the widespread use of such tests is in fact changing how the general public views race (genetically determined) and/or how individuals socially construct their self (social psychologically speaking) in everyday life. In short, both of these issues deserve more large-scale study and analysis, most especially as they may contribute to alienation, detachment, self-isolation and the curtailment of the evolving self. Take Dolores as an example: a stone-cold Chicana from the East Side Barrio in San Jose, Califas. Her sisters purchased a genetic ancestry test and the results documented their family's 50% Apache ancestry. Since Dolores became aware of that, she has all but dropped her Chicana identity and become active within the local Native Advisory Council. Now let’s be clear I am not pitting Chicanos against Native Americans; this is not my point at all. My point is focused on how it is that in the evolution of the self (in a social psychological sense), people who take the genetic ancestry test suddenly find themselves presented with new information about their genetic make-up and are immediately impacted by the new information; they “stop the world” and begin to question common assumptions about who they really are and what they stand for. Consumer recipients of new ancestry information like Dolores are often transformed on the spot, experiencing a cognitive shift about common assumptions, what Nietzsche calls a “transvaluation of values,” adopting a new set of values predicated on a new vision for one’s future self-development and evolution of self. Prior to the test results, Dolores identified with her Chicana/Mexican heritage; she was generally aware of her Native heritage through conversations with relatives in California and in New Mexico. The genetic test results have enabled her to rethink/expand/alter her personal and social identities; the results are the fall of one identity (Chicana) and the rise of a new identity (Apache, Native-American Chicana), a more empowered self. From a social psychological perspective, with new information about her ancestry, Dolores transformed from a softer identity to a much stronger one and she is a lot clearer and stronger, empowered if you will, about whom she is and what she stands for as she looks out into the future. Fact is, people with these experiences often look out at the rest of their lives with a new found purpose not yet clearly defined but certainly impacted by a truer self-esteem. Now take the case of Juan in his own words: “My self-development has been problematic since birth and I guess not yet fully realized because I have always lived with the question, “What makes a Mexican a Mexican?” Born in Querétaro, raised and elevated to full teenage-hood as a chilango in Mexico City, I am the grandchild of Asturian immigrants to Mexico. Half of my brothers, bless their hearts, stick to their Spanish heritage and way of speaking. I always suspected they “cling” to it as a form of distinction from the rest of the ‘natives.’ This is indeed a widespread belief among Mexicans of any European descent in Mexico, so there you have it.” You may be interested to know that I know a family of five in South Texas, each with a different Texas accent. Much like Dr. Doolittle, I have observed that accents are tied to values and ideological beliefs. As Juan grew in consciousness in early developmental years, “I started feeling uncomfortable with such consideration that at best cherished my Spanish ancestral side as a source of pride and identity–nothing wrong with that–and at worst accepted the long held belief that the Mexican middle and upper-classes, that in order to be better, you have to be the more European and whiter. Hey, not their fault that it was an official policy of Mr. Porfirio Díaz during the late 19th Century to whiten the nation, blanquear la raza, to improve la patria. While Díaz was ousted at the onset of the Mexican Revolution, the country never quite got rid of the idea of the blanqueo: ¡Ay! comadre, mire nomás que chulo niño tan blanquito y con sus ojitos azules…” Juan continues: “I have always remained proud of my ancestral roots (ironically the poor and dispossessed peasantry of Northern Spain), but I also came to the realization that having been born in Mexico, I was a Mexican, with a Mexican self. And despite being güerito, or a light-skinned Mexican, I would not let anyone question my Mexicanidad.” Having lived in California for the better part of the last 20 years, he has continued consciously to embrace the Mexican identity. Conversely, Juan’s son took the DNA test, and as suspected, he had a 99% European background, with–to Juan’s delight and surprise–a 1% Native American marker. Perhaps a mischievous ancestor traveled in colonial times to Mexico to come back with a regalito. Juan refuses the concept that Mexican-ness ought to be defined solely in terms of genetic ties to ancestral peoples of Mesoamerica, and he salutes and celebrates the profound relationship between the current identities present in Mexico and the United States regarding being Mexican and those cultures and peoples. Brown, the color, bronce, if you prefer, like Vasconcelos once did, is to be celebrated, admired and unequivocally acknowledged as a marker of identity. A Mexican can claim to be Spaniard, indeed, but unfortunately it will carry with it a colonial legacy of a caste-like system that so much determined the development of a society where privilege and injustice has so much hindered the equitable distribution of the wealth of the nation. Juan has chosen to distance himself from such insidious perception. Let me be clear: scientifically speaking there is no common gene pool for "Spaniards" or any other grouping for that matter. In other words, there is great genetic, linguistic, and cultural variation among all Spaniards, past and present. First off, the Spaniards from south of Madrid (the largest geographic area) were all the product of mating with " North Africans," as they were conquered, colonized, and ruled by the Moors (Moros) for over 900 years. This makes them "mestizos" or people who are the product of two distinct peoples. And, nearly all "Spaniards" who came in the early years of the Conquest of the Americas (when Mexico was settled) and who came in search of wealth and to explore the new world are from the province of Andalucía in Southern Spain, and for sure all the "Great Conquistadores," Cortés, Alvarado, Pizarro, etc., the great oppressors, came from the same area in Southern Moorish Spain, specifically the towns of Trujillo and Badajoz, this last one itself a Moorish name, in the province of Extremadura. So that, for example, in beginning any line of inquiry about, “What makes a Mexican a Mexican?” if your parents and their parents are born in Jalisco, Mexico, with a lineage of ancestors in both Mexico and in that region of Spain, anyone claiming to be “Spaniard” must also take into account whether or not their ancestors come from northern or southern Spain, for that divides many of the gene pools of Spain since the 13th century. Again, generalized "tests of genetic inheritance" (like the human genome project, FamilyTreeDNA.com, or Ancestry.com, etc.) do not account for these fine points. This is another way of saying that Mexicans from Jalisco, Mexico, (with traces of Western European DNA) are likely closer descendants of North Africans, for example. Claiming to be Spaniard also stakes a claim to the likelihood that one is of Moorish descent (nearly 1000 years of intimate social interactions); however, this does make them at least partially “Spaniard.” But again, let’s not forget that DNA testing of Spaniards is providing proof that people from Spain are really from everywhere else, just like all other groupings of peoples, how else can I put it? From a social psychological perspective, I’m beginning to get the sense that the genetic testing industry (groups that gather DNA samples from people as seen on television) is causing a shift in the identity of individuals in American society, for those who remain perplexed about who they are or what they stand for; you might even say the project is causing a breakdown in social identity. As a direct result in what the project is reporting to individuals you are hearing more and more people in daily life break down their DNA when asked, “What is your ethnic background?” “I am 20% this and 35% that, etc. just as in the commercial for FamilyTreeDNA.com as seen on TV. It’s a very peculiar time we live in. Alongside alienation caused by modern day social media, we now have this to contribute to the loss of identity. You might say that when a Mexican American born of Mexican parents in Jalisco with a long lineage of Mexican ancestors says he is “Spaniard” projects such as Ancestry.com gives them a way out of not having to identify with being Mexican. Would be “Spaniards” who find the experience of being labelled as “Mexican” stigmatic prefer this logic, whereas Latinos who call themselves Mexican Americans or Chicanos will correct people who refer to them as “Spaniards” by stating “These are not my people!” The process of gathering DNA from people across the globe is at present at least raising many more questions than it can answer at this time. In addition they argue that the more DNA samples they acquire the better the accuracy of their information. But the reality is that just like many other things that have occurred with scientific discoveries, people find an angle for profiting by keeping science ambiguous; with the advent of Teflon for example, marketers sold the public a bill of goods; in pitching the non-stick pan they simply failed to report that over time it will cause stomach cancer. The unspeakable truth about all of the matching from far off relatives and ancestors is that once you have your DNA tested and recorded in the big data archives of FamilyTreeDNA.com you will undoubtedly locate and/or be discovered by close and distant relatives because the system works! You will receive emails like, “New Relatives Found! We found 111 new mtDNA HVR1 match(es) for Sonny Boy Arias (kit N10134299988)” do I dare click on “View My Matches”? Madre mia! It’s like FamilyTreeDNA.com says “Your mtDNA HVR1 test results can help you find new ancestors and relatives on your direct maternal line (your mother’s mother’s mother and so forth). You will want to look at their family tree and email them to find your possible common relatives and ancestors.” I have to ask myself, “Why on earth would I want to connect with relatives I have never known or have not had any contact with, ever? I moved a good distance away from my tightly knit, well organized huge family for the very reason of not making the “cut off” to family wedding, baptismals, birthdays and sometimes even funerals. Good god, that’s all I need right now is to find out I’m related to a serial killer or cannibal serving 3 life sentences in a nearby high security prison and he is eager to “meat” me. Whether it be human genome research, family or ancestor trees or gathering DNA materials what they are finding is that we are all human, but it serves well those who continue separating the world in a Spencerian way in higher and lower specimens of the species. It contributes little to the discussion on identity that is fundamentally a cultural phenomenon where phenotypical elements are at play. Genetically speaking, the Mexican gene pool is as diverse as it gets: from the Mayan, to the Paipai, to the Nahuatl and to the descendants of European immigrants, all of them culturally defined and genetically diverse. In other words, I might not be the descendant of Netzahualcoyotl, but I am darned proud of his insight and sophistication.  Sonny Boy Arias, who writes science friction to educate, amuse and enrich, is a stone-cold, very self-aware Chicano and a dedicated contributor to Somos en escrito via his column, Chicano Confidential. Copyright © Arts and Sciences World Press, 2018. Below the break are some relevant sources that may be helpful and interesting in performing a search for Mexican identity.

DTC Genetic Testing Companies Compared https://wiki.uiowa.edu/display/2360159/DTC+Genetic+Testing+Companies+Compared Shifting Winds: Using Ancestry DNA to Explore Multiracial Individuals’ Patterns of Articulating Racial Identity, 2017 http://www.wcupa.edu/DNADiscussion/documents/identityInteracial.pdf The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States, 2015 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4289685/ The Genetics of Mexico Recapitulates Native American Substructure and Affects Biomedical Traits, 2014 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4156478/ Genetic Ancestry Testing and the Meaning of Race, 2016 (12:21 minutes) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQlmX7gvYRA Latinos Get Their DNA Tested, 2016 (4:59 minutes) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LCc1N52zSLg New Mexico Hispanics discovering and embracing their indigenous roots, 2016 http://www.santafenewmexican.com/life/features/new-mexico-hispanics-discovering-and-embracing-their-indigenous-roots/article_b951edd4-8002-5d15-876e-83730b71adcb.html

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed