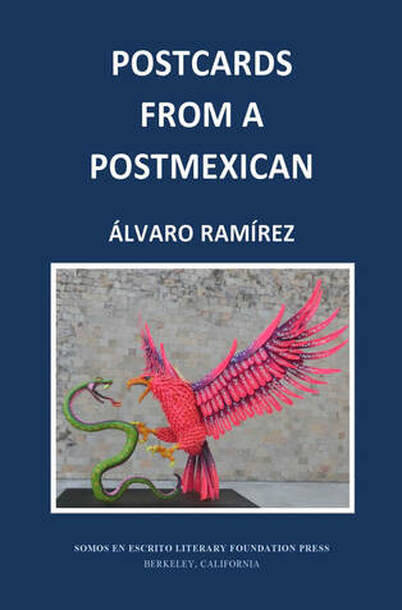

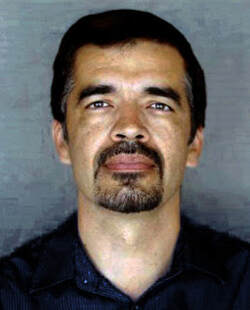

How the Holiday Season is Changing the National Identities of Mexico and the U.S. If you have traveled abroad lately, you may have noticed that national identities are becoming a bit vague. The cultural uniqueness that used to distinguish one nation from another has been quickly disappearing thanks to the accelerated pace of cultural contact brought about by globalization. Mexico and the USA illustrate this well as we go through the holiday season. Millions of Mexican immigrants, legal and undocumented, as well as tourism between both countries have created cultural contact zones unlike any in human history. As they have settled in these areas of the United States, Mexicans have adopted American habits even as they have maintained much of the cultural heritage they brought with them. For example, they love Thanksgiving turkey and on Black Friday you can find them shopping like crazy across the malls alongside Americans. December, however, is a Mexican fiesta north of the border. Los americanos are growing accustomed to seeing and joining the solemn Virgen de Guadalupe celebrations around December 12th and breaking piñatas in the noisy, colorful Posadas on December 15th-24th. Moreover, Mexicans have fused seamlessly La Noche Buena (Christmas Eve) and Christmas Day, so they can have their tasty tamaladas and receive the birth of Jesus with tons of gifts the good old American way. As many Mexican immigrants return to visit family in Mexico, they bring along these new cultural customs, especially their sons and daughters who were born and raised in the United States. You can see the influence of these new cultural ways in small towns and cities across the country. Mexicans now have their Buen Fin, a clone of Black Friday, and on Thanksgiving more and more people are preparing a turkey dinner a la americana or go to restaurants that offer a similar menu. As for Santa Claus, Christmas trees and carols, they are the norm everywhere. It may seem strange, but in Mexico City and Cuernavaca, you can even go ice-skating downtown! You could say Cinco de Mayo was the first cultural celebration to bring Americans and Mexicans together, and that lately Día de los Muertos and Halloween have provided more cultural glue that binds people on both side of the border. But it is the long holyday season at the end of the year that is having the biggest impact on our identities and how we see ourselves in Mexico and the United States. Mexicans who visit the U.S. and Americans who travel to Mexico are bewildered by this turn of events. National identities may still be around, but the unique cultural elements that separated them are blending fast and, in some cases, disappearing and becoming a thing of the past.  Somos en escrito Literary Foundation Press published a compilation of Álvaro Ramírez’s observations on changing cultural traditions: Postcards from a PostMexican. Click the cover above or visit Amazon to buy a copy. This postcard first appeared on Álvaro Ramírez’s Postcards from a PostMexican blog on December 24, 2019. This postcard was published under the title “How the Holiday Season is Changing Mexican and American Cultural Identities” in Cultura Colectiva, a Mexican online magazine, on January 2, 2020.  Álvaro Ramírez is from Michoacán, México. He migrated with his family to Ohio as an adolescent. He obtained a BA in Spanish and Education at Youngtown State University, and an MA and PhD in Literature from the University of Southern California. He has taught at various institutions including the University of Southern California, Occidental College, and California State University, Long Beach. Since 1993, he has worked at Saint Mary’s College of California where he is a Professor in the Department of World Languages and Cultures. He specializes in Spanish Golden Age and Latin American literature as well as Mexican Film and Chicano Cultural Studies. He also serves as Resident Director for the Saint Mary’s College Semester Program in Cuernavaca, México. In 2016, Prof. Ramírez published a collection of short stories, Los norteados, which received an Honorable Mention Award at the 2017 International Latino Book Awards. In addition, he has edited two online publications of Conference Proceedings: Imágenes de postlatinoamérica, volumen 1 (2018) and Imágenes de postlatinoamérica, volumen 2 (2019). He has also published articles on Don Quixote, Mexican film, and Chicano Studies in several academic journals.

0 Comments

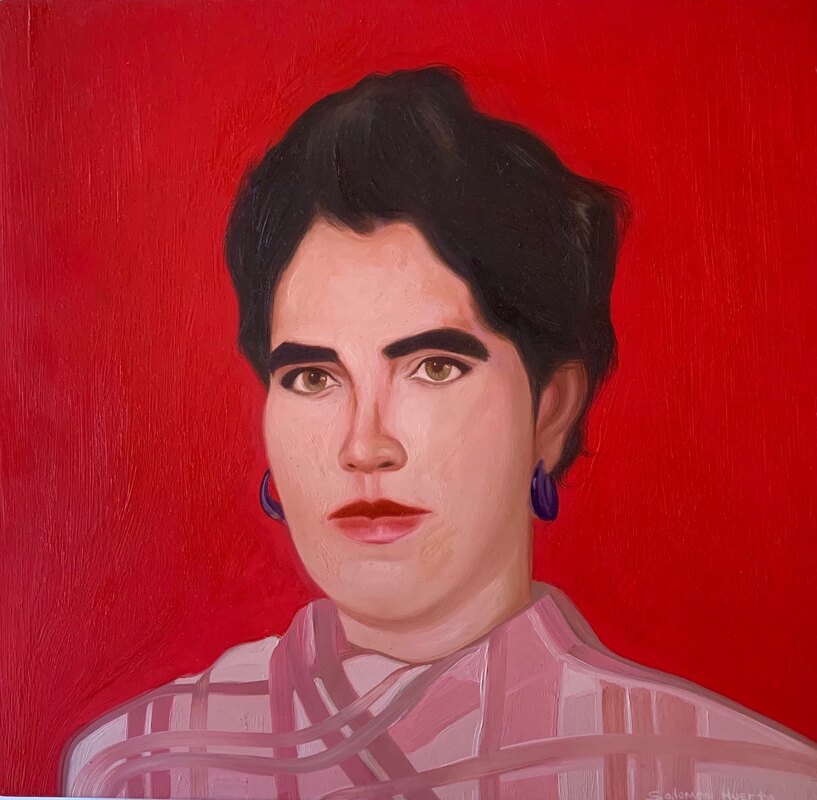

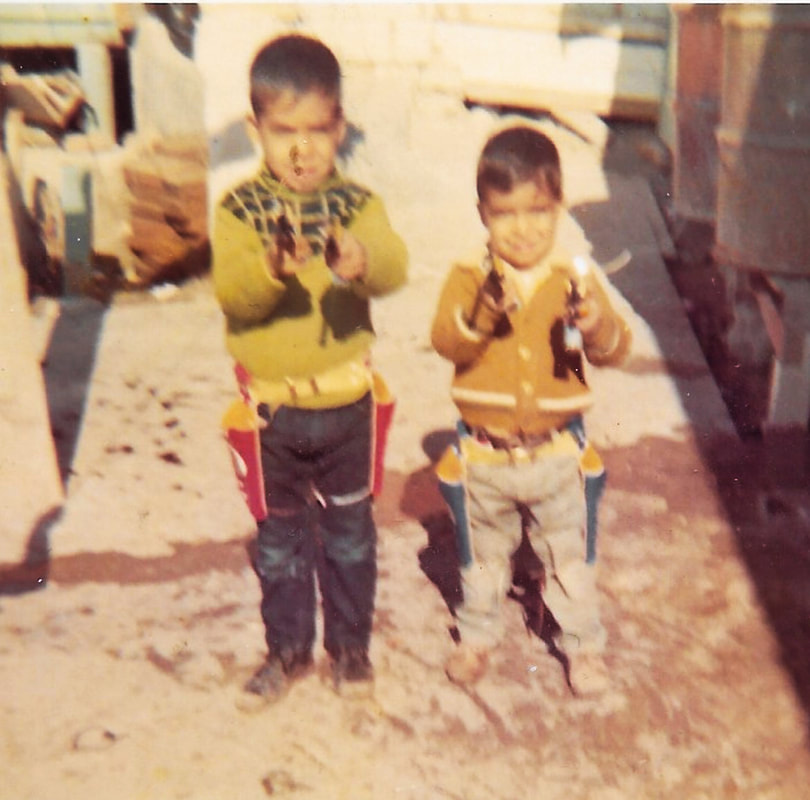

Brick-by-Brick: An Ode to My Mexican Mother, Carmen Mejía HuertaBy Álvaro Huerta My late mother, Carmen Mejía Huerta, built her own home, brick by brick, in Mexico. Too poor to secure a piece of the “American Dream” in el norte, during the mid-1980s, while residing in East Los Angeles, she decided to build her own home. When she told my siblings and me—all eight of us—about her ambitious plans, we all thought she had gone mad. “What are you going to do in Tijuana all by herself?” I asked. “No te preocupes demasiado,” she said. “Voy a construir un cuarto para cada uno de ustedes.” Our family, like many Mexicans, has a strong bond with Tijuana, Baja California—a poor, yet vibrant border city where countless immigrants first settle before making their arduous journey to el norte. My Mexican parents first migrated to Tijuana from Zajo Grande, a rancho in Michoacán, during the early 1960s. They fled a bloody family feud that claimed the life of my uncle, Pascual. As a so-called “good wife,” my mother relocated with my father (Salomón, Sr.) and his large family—parents and nine siblings—to el Cañon Otay in la Colonia Libertad. Unlike the U.S., the poor in Latin America mostly live on the hillsides, while the affluent reside in the city core. Once settled in Tijuana, she acquired an American work visa as a doméstica (domestic worker). While toiling for white, middle-class families in San Diego, California, she left us at home with our familia--immediate and extended. In her absence, my older sisters (Catalina, Soledad and Ofelia) took on the “mother” role of cleaning, cooking and caring for the younger kids (Salomón, Rosa and myself). They also worked in their teens, sacrificing their education—a common practice in developing and underdeveloped countries. As a risk-taker, my mother, during her fifth pregnancy, arranged for me to be born in el norte. Accessing her kinship networks in the U.S., my mother delivered me in Sacramento, California. Isn’t San Diego closer to the border? Despite this conundrum, having a child born in the U.S. facilitated the process for my immediate family to successfully apply for micas (green cards) in this country. Once in the U.S., my mother continued to labor tirelessly as a doméstica while my father never surpassed the minimum wage ($3.25 per hour) in dead-end jobs, as a janitor and day laborer. Due to their lack of formal education and limited English skills, accompanied by low-occupational skills, my parents applied for government aid and public housing assistance at East Los Angeles’ notorious Ramona Gardens public housing project (or Big Hazard projects). Tired of the overcrowding, abject poverty, violence, drugs, gangs, police abuse and bleak prospects that plagued the projects, my mother decided to return to the motherland, Mexico, as a refuge. During my freshman year at UCLA, I received a call from her, informing me that she purchased a small, empty lot in Tijuana to build her dream home. While initially shocked, thinking that she wasted her money, I requested an emergency student loan to support her dream. Given her unconditional love for me (and my siblings), I acted without hesitation. On the loan application, I wrote: “Help Mexican immigrant mother to escape the projects.” Not long after acquiring the plot, my mother gave my siblings and me a tour. Like a recent graduate of UC Berkeley’s architecture program, she presented her design plan and created a visual image for us of her finished home. “Aquí es donde irá la cocina y la sala por ahí,” she said with confidence, as we surveyed the uneven, dirt-filled lot. We listened with deep skepticism. In retrospect, we should’ve never doubted her. This is the same woman who, as a 13-year-old, hit a potential kidnapper in the head with a rock to escape. If he would’ve succeeded—abducting her for several days and returning her home—she would’ve been forced to marry him to “save her honor” or the “family’s honor”—a barbaric practice that continues to the present in many parts of the world. Fortunately for my siblings and I, she married a handsome man, Salomón Chavez Huerta, at the tender age of 14. Moreover, this is the same woman who worked as a doméstica in the U.S. for over 40 years to provide for her family. She’s the one who forced my father to take my older brother, Salomón, and I, as lazy teenagers, to work as day laborers in Malibu so we could appreciate the importance of higher education. “Si no los llevas al trabajo,” she threatened my father, as he watched his Westerns on T.V., “entonces los llevaré.” For many years, my mother—with the help of the family—slowly built her dream home. First came the cement foundation and then the walls. The roof followed. Then came the windows and doors. Not satisfied with one-story, she built a two-story home. My father included a guest house in the back. While she initially protested, she later appreciated having extra units to rent. Defying the odds, she transformed an empty space with rocks, used tires and broken glass into the most beautiful home on the block—probably in the entire colonia. She hired and fired workers, fixed leaky faucets and remodeled, (re)painted the walls and changed the kitchen cabinets like there was no end. For the family, we considered the Tijuana home our mother’s obsession. Yet, for my mother, it represented a Mexican dream come true. This home symbolized the product of a long journey for a woman without formal education and lack of employment opportunities to get ahead. At the end of the day, she wasn’t going to let anyone derail her dream. For the first time in her life, my mother cleaned and improved her own home, instead of the affluent homes of the privileged, white Americans she “served.” I only wish I could see her beautiful face one more time so I could tell how proud I am of her.  Álvaro Huerta holds a joint faculty appointment in Urban and Regional Planning and Ethnic & Women’s Studies at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Among other publications, he’s the author of Defending Latina/o Immigrant Communities: The Xenophobic Era of Trump and Beyond. He holds a Ph.D. in City and Regional Planning from UC Berkeley and an M.A. in Urban Planning and a B.A. in History from UCLA. He’s been featured in Somos en escrito for his fiction and research publications. Welcome to My Worlds |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed