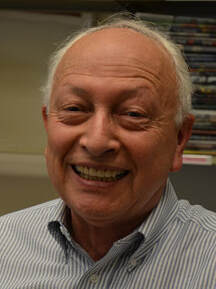

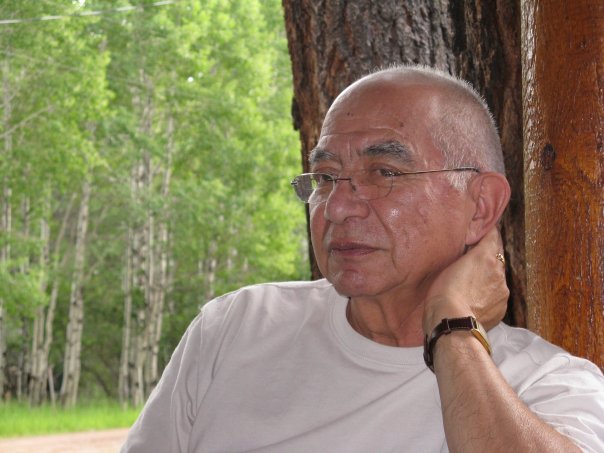

Arturo Madrid: Educator, Mentor, Champion of Latino LiteratureBy Roberto Haro It is important to celebrate the accomplishments of a remarkable man, a pioneer, an erudite spokesman for Latinos in our society, and a national leader in different ways. It is not the intent of this piece to catalog the accomplishments of this outstanding individual. That has already been done. Rather, these comments will be ad hominem to underscore why he is such a special person. Arturo Madrid is one of those rare individuals who comes along once in a generation. From humble beginnings in New Mexico, he achieved much as an academician, and as a trailblazer and role model for so many in our society. Anyone who has read his impressive book, In the Country of Empty Crosses: The Story of a Hispano Protestant Family in Catholic New Mexico (Trinity University Press: San Antonio, 2012) will appreciate the double helix challenges he faced and overcame. (Arturo now lives in San Antonio, Texas.) Latinos, an inclusive term used to include people from or with ancestral ties to the Caribbean, Central and South America who share a common linguistic and cultural background are an ethnic minority in most places in the United States. In some geographical and politically defined areas, they are now a significant majority. However, where Arturo was raised, he and his family were marginalized in two senses. First, they were part of an ethnic minority, and second, they were among a lesser group of religiously oriented folk in New Mexico. Arturo has often spoken about being one of the “others.” For some, that meant he and his family were part of a marginalized ethnic minority. But for those who know him, and have read his book, he and his family were the others in a double sense. Marginalized by the larger society because of ethnic origin may be a sufficient challenge for many. But practicing a faith different from that of the local ethnic enclave is an added burden. Faced with these obstacles, Arturo endeavored to persevere and succeeded in becoming, a respected scholar, and an exemplary leader. Consider for a moment what Arturo achieved when he earned the Ph.D. He became one of the “Twelve Apostles,” a term of respect and endearment that several Chicano scholars, especially the inscrutable Tony Burciaga, used to refer to that select group of Latinos who earned their doctorates and became leaders in American higher education. Because of their efforts, these early Latino pioneers in education opened pathways to higher educational attainment for many young Latinas and Latinos. In this sense, Arturo contributed much as a teacher, as an astute spokesperson for our community, and as a change agent. Consider what Arturo did as a teacher. There have been few scholars responsible for opening the minds of students at American universities by introducing them to the literary expressions of an important and expanding ethnic minority. Whether by assignments or recommendations, Arturo made college students and others aware of Latina and Latino writers. His approach was to highlight and underscore the wealth of literary expression that our essayists, poets and novelists prepared. At the time he was doing this, few others in major research institutions were doing so. Instead, it was chic to do research and prepare treatises on Latino writers from Spain, the Caribbean, and South America. Meanwhile black literature that expressed their experiences in America was just beginning to draw the attention of researchers, scholars, and graduate students. Arturo began a consciousness raising movement in his teaching, writing and speaking engagements. His goals were controversial, and even considered radical, when he began to kindle an awareness of Latino literature in America, and the contributions of Latina and Latino writers. This sentience stimulated several important activities. The experience of Latinos in the US was a victim of benign neglect by scholars in the traditional disciplines. Historical treatises had been written by American scholars that briefly made mention of the “Spanish speaking” and “Hispanics” in the US. It was little more than condescension. Arturo, and a few of his colleagues, changed that. They taught and informed anyone who would listen about Latina and Latino essayists and poets and their contributions to American literature. Librarians at colleges and universities were among the first groups to tap into these writings because of Arturo’s efforts. Library collections at colleges and universities like UC Berkeley, UCLA and the University of Texas at Austin soon developed programs to collect, catalog and organize Latino literature. By 1970, public librarians began to consider the works of Latino novelists and poets based on what they heard from scholars like Arturo. Gradually the major publishers and literary agents started to identify writers like Piri Thomas, Gloria Anzaldúa, Sandra Cisneros, Rudy Anaya, Américo Paredes, Lorna Dee Cervantes, and Tomas Rivera. By the mid-1970s, poets like Alurista, Cherrie Moraga and Raul Salinas were recognized as significant writers. Wherever Arturo visited, lectured, or engaged in conversations with colleagues, friends, and influential people, he commented on the richness of Latino literary expression, and highlighted our established and promising writers. Arturo was among the first scholars in American higher education to identify creative Latino writers and their contributions to American literature. And he did so at a time when Latino literary expressions were not considered significant by leading academics at major universities. He was, therefore, a substantial change agent. Arturo realized that a structural effort was required to ensure that our literature was recognized, organized, and preserved for access and dissemination to a wide audience. And he understood that elevating the Latino experience in America through scholarship and especially artistic and cultural expression was essential for this body of knowledge to achieve its proper place in American culture and history. To improve the information and knowledge about Latinos in this country, and find ways for our people to achieve leadership roles, Arturo made a decision to approach key decision makers. What did he decide to do and why? In his classic book, The Power Elite (1956), C. Wright Mills postulated a theory about how power and influence were exercised by the interwoven interests among the corporate, military and political elites. To introduce new ideas and perspectives about Latinos that would lead to desired change, of necessity, American elites had to be involved. This Arturo accomplished by becoming involved with influential decision makers in the foundations, and among leaders who served on policy boards of national organizations. Penetrating the governing boards of significant national organizations that influence and condition the economic, political and social directions and activities in this country is a complex and challenging process. To achieve any measure of success in such an endeavor not only requires keen intellect, but patience, tolerance and above all tact. Gradually, Arturo became known and respected by influential foundations like Carnegie and Ford, and by leading national associations like Educational Testing Service and The Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation. By determination, erudite expressions, and wit, he gained the confidence and respect of key board members within these national associations. He was and continues to be a magnificent Latino ambassador to our nation’s elites, and a successful explicator of the unique Latino experience in the US. Moreover, he explained the heterogeneity of the Latino community. Statisticians love to aggregate data to establish broad categories that are expedient for their purposes. However, such numerical compilations result in descriptors that for the sake of convenience tend to skew perspectives about people. Perhaps the classic example of this process is the way the term “Spanish Speaking” was developed by the Bureau of the Census to pigeonhole Latinos. When that term was challenged, the Bureau of the Census devised a new term, “Hispanic,” to categorize Raza. Both terms were used to define and group Latinos in the US as a monolithic entity when in fact our differences are substantial. And it was done with vigorous objections against it by Leo Estrada, then a senior member of the Bureau of the Census, and without any significant input from leaders in different Latino communities. It was such policy decisions made at the national level that often led to misperceptions about who Latinos are. Arturo helped to challenge these prevailing stereotypes, and was instrumental in helping national leaders and policy makers understand and appreciate the norms and orientation of different enclaves within the Latino communities in the US. Questioning a bureaucracy as large and powerful as the Bureau of the Census can be a herculean task. Yet, Arturo and a precious few of his peers did so, but not without subtle and overt forms of opposition and resistance. It is worth mentioning that even though Arturo challenged the federal government, its leaders were sufficiently impressed by his efforts to hire him at a later date. The above accomplishments by Arturo surface two other aspects of his special status in the Latino community, and in the larger society as well. He is a unique leader and mentor. Respected for his academic endeavors and knowledge, Arturo was selected for leadership roles in several major organizations. As the founding CEO for a new endeavor, Arturo demonstrated an acumen for progressive management and organizational development. His impressive performance as a CEO reveal the qualities that constitute a mature and successful leader. Under his direction, the Tomas Rivera Center achieved national prominence as an outstanding educational policy institute. It placed research about Latinos in the US on a new plateau that drew the attention and support of major foundations and funding bodies. And in his activities as a leader there was imbedded the dedication to helping others. These are visible indicators that the personal and professional qualities that made him an outstanding teacher and leader, also contributed to his role as a superb mentor. Too many nationally recognized scholars and academicians known for their subject expertise and focused research have neither the time nor the desire to work closely with students and promising new professionals. The path to success at major research universities is predicated on winning grants, publishing research in the best scholarly journals and in university presses. Few research universities recognize or reward scholars for mentoring. Latinas and Latinos are a small percentage of students engaged in programs leading to the Ph.D. at the most elite universities in the US. Many of these Latinos bemoan the lack of adequate mentoring while doing their doctoral graduate work. It is in this area that Arturo has been a remarkable resource for these and other students. In his various capacities as a faculty member, academic administrator, organizational leader, and board member, Arturo has always found time to interact with students in meaningful and constructive ways. He is known as someone dedicated to helping students and others sort through the numerous challenges they face in achieving their goals. Whether as an inspirational speaker, as the leader of small group discussions, or as a participant at an academic function, he has time to listen to students and others, including community activities and Latinos in elected or appointed public roles. There is something about Arturo’s manner than encourages communication, and confidence. He is often searched out by people seeking advice regarding their educational ambitions, or other goals. A patient and keenly analytical thinker, Arturo listens carefully to those who ask his advice, or just relate their concerns. He makes time to fully comprehend the issues, and his responses are always measured and to the point. In addition to this, he draws on his experiential knowledge to help. And where possible, he will direct a petitioner to a friend or colleague with the proper expertise. And when he does recommend someone, it is always an obliging person willing to help. And on numerous occasions, Arturo will follow-up and determine if the person who approached him for help has received the assistance she or he needed. Mentors like Arturo are rare. The more progressive institutions of higher education have places and roles for accomplished, well rounded distinguished academics. Endowed chairs are established that provide enormous flexibility for the recipients to make significant contributions in their chosen endeavors. For some, they devote their time as holders of these chairs to do research, or travel to interact with other specialists like them in the production of new knowledge, or in new ways to organize knowledge. And for others, like Arturo, it is a license to do all of the above plus meet and share with students, his colleagues, and others in formal and informal settings. It is through his travels and interactions with a wide spectrum of folk in our society that Arturo excels. He stimulates new ideas, and also channels the directions of people seeking new ways to communicate their perspectives with a broad audience. Arturo is a successful and articulate spokesperson for his perspectives about Latinos in the US, and as a conduit to those continuing to study and share their ideas about Latino communities across America. An often used cliché about the “Renaissance Man” is so appropriately descriptive of Arturo. While he may retire, this Renaissance Man will always be in our hearts and minds.  Roberto Haro, a longtime activist in education and social concerns affecting Latinidad, is an essayist and author of several novels dealing with war dramas, crime mysteries, historical fiction and romance. He lives and writes in Marin County, a part of the San Francisco Bay Area.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed