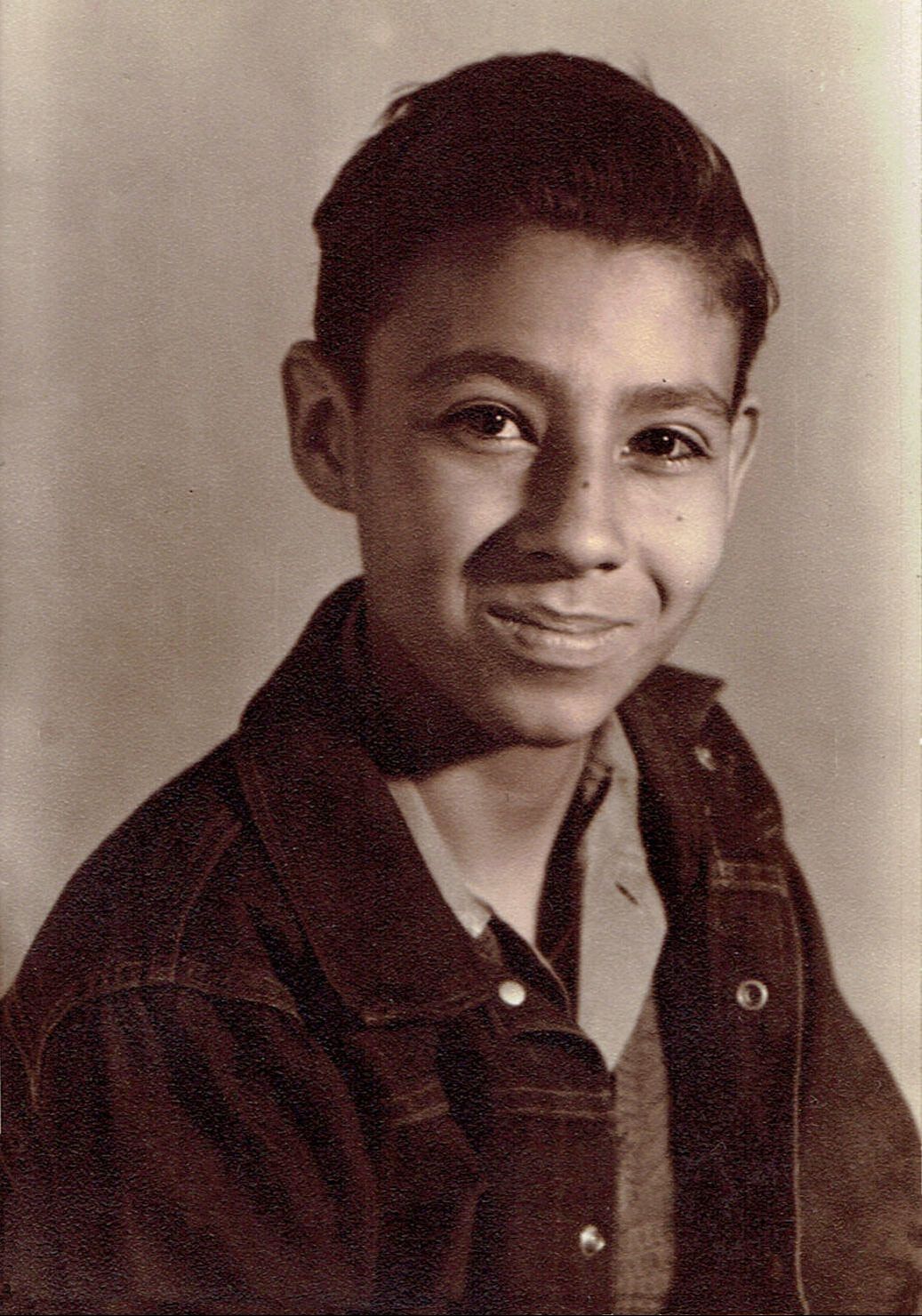

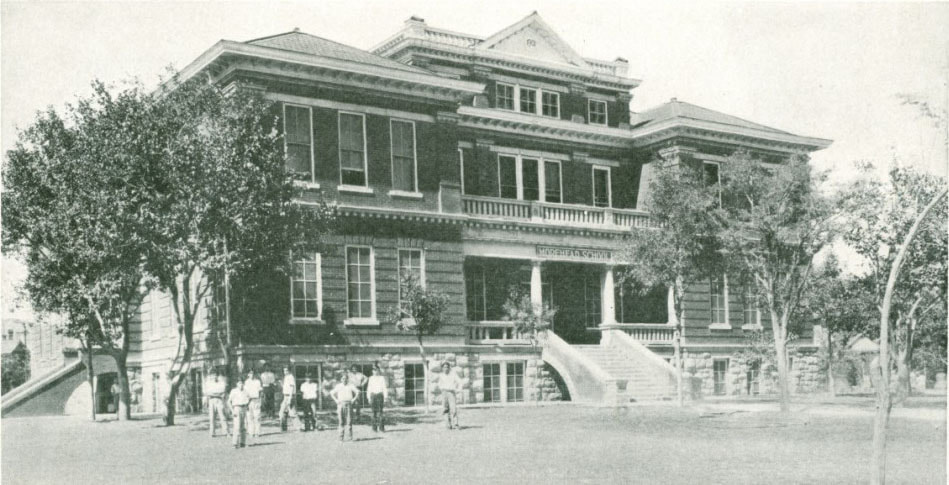

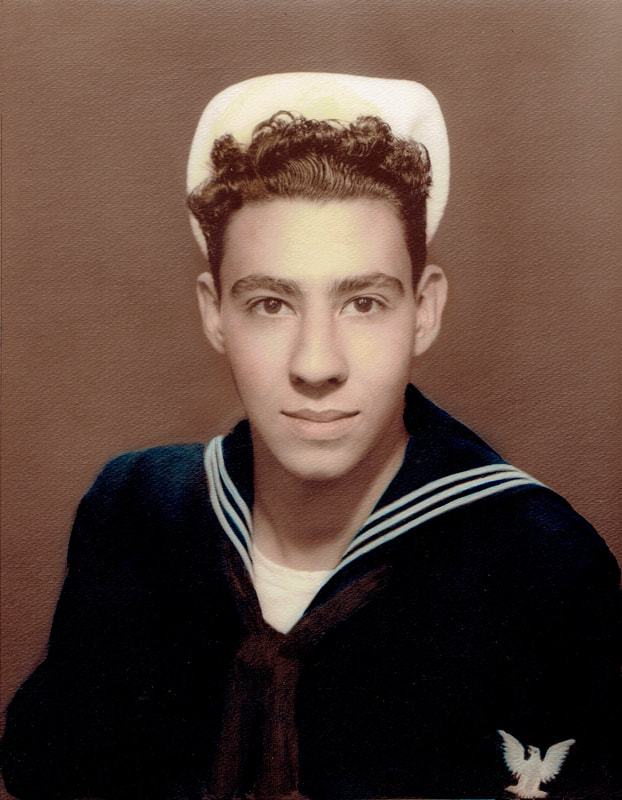

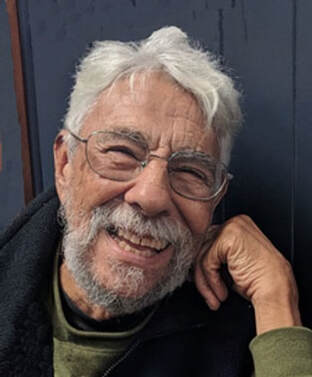

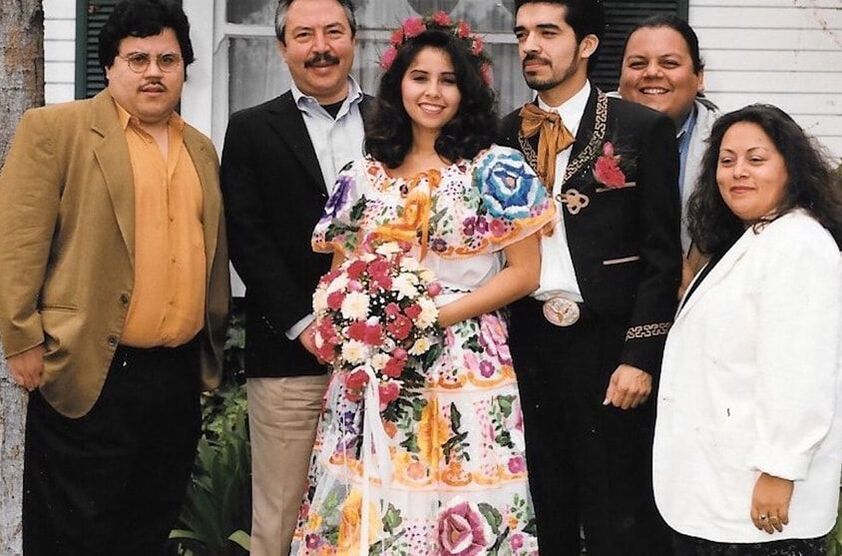

Memories of a Mexican Boy From El Paso: Making It at the University of Texas in the 1960s by Daniel Acosta, Jr. Prologue With apologies for confiscating a part of Norman Podhoretz’s memoir title for my own use, I knew when I started the three-year B. S. pharmacy program at the University of Texas in the fall of 1965 it was make or break for me. I had no close friends in high school and never had a date. I was not entirely a loner in high school; I talked to my classmates and acted friendly. It was not until my junior and senior years that I joined a few school clubs and became more involved with activities I enjoyed, such as the Science Club and the Chess Club. Academically, I did well at Austin High School; I graduated as one of the top seven students in a class of 330 students—four white males, two white females, and me, the lone Mexican American. In 1963, Valedictorian and Salutatorian students were not selected for the first time in El Paso high schools; instead, the top 2% of the class were honored at graduation. I never learned who was number one. Two weeks after graduating from high school, I was on the bus to take me to my freshman classes in English and American History at Texas Western College in the summer of 1963. The so-called “high school on the hill,” which us Mexicans dubbed the College, was our first real chance to experience the college experience. TWC is really a beautiful campus, if you like the desert with colorful cacti and mesquite bushes and limited trees and grass. The small, jagged foothills of the Franklin Mountains near the campus add to its beauty—and thus its nickname. The architecture of the buildings is quite unique with a strong Bhutanese influence—distinctive, red-tiled roofs. Many of the graduating Anglo students went to more glamorous schools away from El Paso. Beginning College For the next two years I caught the early morning Beaumont bus on Piedras Street a block away from my home. The bus went south down Piedras to Five Points, where there was a Sears for shopping and the Pershing Theater. Throughout my early teens I spent many Saturday afternoons watching many B westerns and crime movies. In June 1963, now that I had graduated from high school, I was ready for a better class of movies to see. I remember vividly the first showing in El Paso of Cleopatra with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton at the Pershing. I had read in the El Paso Times that this Hollywood epic was a movie to not be missed—it had Taylor and Burton who were having a torrid love affair during the making of the film. Eddie Fisher, the famous pop singer, divorced Taylor soon after the movie was released. Because their affair was in the news on a nearly daily basis, I knew that I had to see the movie. I got to the Pershing about two hours early to wait in line for a ticket. By the time I arrived there was a long line of people. I saw a group of high school girls who were laughing and waving to their boyfriends to come to the front of the line. “Johnny, did you bring enough money to buy the tickets? Hurry up, we saved some spots for you in line,” yelled one of the girls. As three of the guys pushed and shoved to get to the girls, other people in the line screamed for them to get back to the end of the line. This got the attention of the security guards who rushed to grab the guys and moved them away from the loud and angry people. Eventually things quieted down and people waited patiently to get their tickets. That was my first taste of a so-called mob scene. It was really not that much of a thing; it was only people trying to butt into line. It broke the monotony of standing in line and made me more excited to see the movie. I later learned during my summer school classes, the manager of the Pershing, Mr. Miledi, was a part-time chemistry teacher at the College. Everyone called him “No Bugs My Lady,” a popular ad at the time on radio and TV for an insect spray. I remember seeing him in the fall semester when I was taking freshman chemistry. After leaving Five Points, the bus took a right on Yandell Drive heading west to the plaza in downtown El Paso. In the middle of the plaza was a round, waist-high fountain enclosure, which was dry most of the year. It was a big attraction for kids and tourists because a lonely, foul-smelling alligator was stuck right in the middle of the fountain looking for food to be thrown to him. Of course, there were signs warning people to not feed the alligator, but it was done all the time. I felt sorry for the alligator; I did not look at it while I waited for the Sunset bus which stopped at a medical clinic, a few blocks away from the College. On that bus were many maids and yardmen who worked in the more expensive neighborhoods of west El Paso, near the College. When I come to think of it, my college education really began with my observations of people on the buses I took to and from TWC. Because the Beaumont bus began near William Beaumont Army Medical Center a few miles straight north up Piedras, there were a variety of people who used the bus: people who worked downtown in major department stores, banks, insurance offices, etc., and those people from South El Paso who used the bus to get to work at the Medical Center and at Ft. Bliss—one of the largest Army bases in the country. They were mainly Mexicans who did cleaning and yard work for the Army. Tina, my older sister, became a civil servant, and eventually became the executive manager for the main EEO office at Ft. Bliss. I got to know the bus driver, who always asked how I was doing with my courses. After I graduated from pharmacy school at the University of Texas at Austin three years after leaving TWC, I received a draft notice to return to El Paso for my induction into the US Army at Ft. Bliss. A few weeks into basic training, my platoon had to do some training in the desert, and it so happened that the Army bus was driven by the same driver who took me to classes for those two years at TWC. I could only nod to him because the drill sergeant demanded complete silence in the bus. At least, I knew someone from El Paso during my 8 weeks of training. I had received a graduate deferment to attend the University of Kansas to study for a degree in pharmacology, but the deferment was canceled as the Vietnam War intensified in 1968 and more draftees were needed. Seeing the friendly face of my former bus driver every once and while at Ft. Bliss made my training easier and made it easier to accept my fate if I were to be sent to Vietnam. The country was in turmoil and many student protests were occurring on college campuses. I had thought with my pharmacy degree that I could avoid the Vietnam War and be one of the lucky few to not serve in the military. I was not sent to Vietnam; instead, I served my two years at Army medical facilities in Savannah and South Korea. Several of my Mexican high school classmates were not as lucky as me and were wounded or killed in Vietnam. Minorities across the country were the ones who suffered the most during their service in the military in the 1960s and early 1970s. At Texas Western College Now to the story about my other education to get a degree. After much thought and research about what my major should be, I decided without any advice from my family, teachers, or counselors to pursue a career in pharmacy. That was it; I had made my decision on what I wanted to do; and I developed a plan. To receive a B. S. degree in pharmacy, one did two years of pre-pharmacy coursework at any college, such as chemistry, physics, calculus, English, history, biology, accounting, government, and so on and so on. The final three years for the degree were taken at an accredited college of pharmacy, which in my case was at the University of Texas at Austin after completing my pre-pharmacy courses at Texas Western College in El Paso. The other two colleges of pharmacy in Texas during the 1960s were in Houston. One guess why I chose UT. Even back then Austin was the city to live in Texas. Dallas and Houston did not even come close. After graduation from pharmacy school, I would take the pharmacy board exams, pass them, and become a licensed pharmacist in 1968. Easy—right? The two-year pre-pharmacy curriculum at Texas Western College meshed quite nicely with my plans because the expenses would be minimal to cover, living at home. For some Mexicans like me I felt it was a let-down to not attend a college away from El Paso right after high school; instead, we made fun of the “high school on the hill” and mistakenly thought it was degrading to not go to a “real college.” I was so wrong to think that. Texas Western College was one of the best things to prepare me for the rigors of going to “The University” in Austin, as it is known to native Texans. My family did not have the financial resources to help me much with college expenses, such as tuition, books, bus fare, clothes, lunch expenses, etc. I worked four years through high school as a paper boy and had saved several hundred dollars for my first year of college. I knew that I could not go to a college that was away from El Paso. I realized that if I wanted to attend UT-Austin, it meant working 20 to 25 hours week while I managed a full course load each semester. My next-door neighbor, Mr. Bacon, who I’d known throughout my high school years, got me a job at the Data Analysis Center, which just happened to be across the street from the student union and most of my classrooms. DAC did contract work for the federal government on several defense and scientific projects. I did not know what to expect; most of the guys working there were math, physics, and engineering students. I was a pre-pharmacy major, mostly taking biological and business courses to prepare me for admission into pharmacy school two years later at the University of Texas. As I was going to the water fountain in the main work room at DAC, I heard someone yell out at me: “Hey, Danny. My name for you is now Danny Waters,” Tony winked at me. He told me that he had already seen me get a drink of water twice today and that was now my nickname. I instantly liked him; he was charismatic; and he looked and dressed differently than the rest of us. He wore nice slacks (not jeans) and well-ironed shirts. His haircut was very similar to Cary Grant’s and to the guy who played “Mr. Lucky” on TV. He told me it was a razor-cut, and I could not see a hair out of place. He definitely did not look like a nerdy engineer. Tony was in his senior year, majoring in electrical engineering. It turned out in his junior year he ran for president of the student body, and he won. It was very unusual for a junior to win the presidency and be around when the new president began his term of office. I did not think that Tony really knew what it meant that a Mexican guy had been elected over a white guy. El Paso was definitely a town where whites were more prominent in business and government circles. I never saw Tony use his status with others; we Mexicans at Texas Western College were quite proud of him. My freshman year knowing Tony, when I think back over the years, influenced me greatly. I became prouder of my own Mexican heritage. I was a strong supporter of JFK when he was elected President, and especially, when he appointed the first Mexican American mayor of El Paso, Raymond Telles, the ambassador to Costa Rica. Tony always treated me as an equal and not as a young pimply teenager. When his girlfriend was to start graduate school in geology at the University of Arizona in Tucson, he asked if I could help the both of them move her things to Tucson. I jumped at the offer. Just talking with Tony for that whole trip was so memorable. I was shy and introverted. Intuitively I knew that to be successful socially, professionally, and romantically I had to be more willing to engage with other people and become more extroverted. I began to come out of my shell during my two years of pre-pharmacy coursework at Texas Western College, but without a car and having to take a bus to get to campus every day for those two years I was still at a disadvantage. It became an obsession for me to get a car while I attended college, especially when I would go to Austin for pharmacy school. “Danny, how much have you saved to go to Austin next fall?” asked one of my co-workers at the Data Analysis Center on campus. “I can make it through the first year without working at UT but will have to work full-time in El Paso during the following summer to save more money for the second year.” Actually, my plan was to get one or two jobs in Austin while I was attending pharmacy school for the second year of the professional pharmacy curriculum. I had surprisingly breezed through my first year of classes at UT without having to work like I did in El Paso. I had saved enough money to cover my expenses for my first year at UT. I worked the following summer at a pharmacy in El Paso to build up my savings again. I wanted the extra money from these jobs to buy a car in Austin. Would I be successful? Time and hard work would tell. At the University of Texas I learned about two jobs after my first year at the College of Pharmacy through some hungry and poor pharmacy classmates, who, like me, had to work to get through college. As pharmacy students, it was drilled into our minds by our professors that we were part of the medical profession with physicians and nurses, and we had to show those other two professions that we deserved the same respect they received from the public. A few discount pharmacies were starting to pop up in the 1960s; they were considered to be a negative blot on the more respectable and professional retail pharmacies that had dominated the profession for years. One particular discount pharmacy chain that started in Dallas threw salt in their eyes by opening up their first drug store in Austin. Even its name was insulting and looking for a fight—Ward’s Cut Rate Drugs, which was notably located on Austin’s most famous street, Congress Avenue, looking down the throat at the Capitol a few blocks away. It wanted to hire pharmacy students as employees, and it paid good hourly wages. I applied and got the job. One down, another job to go. I was told about a dormitory for rich girls; the pay was non-existent. Not many students wanted to work there if there were no hourly wages. Instead, a student kitchen worker was paid with meals after the girls ate. If I did not have to buy groceries and cook my own food, this arrangement was right up my alley. I took a kitchen job at the exclusive and pricey Hardin House. I now had my food taken care of each month and I was earning good pay at Ward’s. With these two jobs, I was well on my way in saving money for a car. I did what I always did while I attended UT: go to classes, grab meals when I could, work at two jobs, study, sleep and do it all over again the next day. I had an evening job at the Hardin House and later changed jobs to another girl’s dormitory, starting at 6:30 AM. At both jobs, I closely observed how these co-eds, mainly sorority girls, talked and laughed among themselves as if the kitchen student workers did not exist. At UT, I went to my pharmacy classes in the morning, and in the afternoon, I attended laboratory sections in medicinal chemistry, pharmacology, compounding drugs, pharmacognosy, drug manufacturing, and microbiology. The ultimate senior lab—the Prescription Lab—was a simulated drug store where us pharmacy students learned to read prescriptions, fill the prescriptions, catch any mistakes in the prescriptions, and advise the fake patients/customers on how to take their medications and point out any potential side effects. After classes, I ran back to the dorm to get my free meal before I caught a bus from campus to get to my other job at Ward’s, with its prominent location in downtown Austin. As mentioned earlier, my professors said it was disgraceful and unprofessional to work in a discount pharmacy. Did I really care? I worked there about 15-20 hours a week; I was making good money to get my car. I never thought much about working two jobs. I needed the money to survive so I could live in a city that was the envy of other students living in such cities as College Station—Aggieland; Lubbock—Texas Tech; Waco—Baylor; or my hometown of El Paso—the Miners. I won’t mention the other schools in Houston and Dallas. The problem was that I was not able to enjoy the active night scene my first two years in Austin. Because of my work schedule, my social life in college was not spectacular and if you really want to know, it was sub-par. I did not have a car and that put a real damper on meeting and dating girls. I had a major goal, besides getting my pharmacy degree: get a car and live in style during my last year of pharmacy school. It was the penultimate year that was a bear to endure, but I was getting closer and closer to getting my car. The Hardin House I should talk more about my job at the Hardin House—that exclusive dorm for co-eds that parents paid big bucks to have their daughters fed and protected while they attended the mostly white University of Texas. There were a few Black students at UT in the 1960s. The percentages for Hispanics, mostly of Mexican heritage, were in the low teens. It is now around 23%. I was hired by the head cook, a wonderful Black woman who deeply cared for her student workers and treated us with respect. I looked forward to working each night to hear stories about her life, and she really liked to joke around and laugh with us. However, a few months later a dining room manager was hired to run the entire dining experience at the Hardin House, including the kitchen and the fancy dining room for the girls and their guests. When she was in the kitchen, there was less talking and laughing. I eventually had a run-in with her. Working in the kitchen was sometimes hard and dirty work. The other student workers were at the Hardin House because, like me, we needed the money to attend the great University of Texas, or as stated in the Texas Constitution—a World-Class University! I was the only Mexican student in the kitchen, and the other workers were white and came from small towns in Texas—they did not receive much financial support from their families to make it through college. As a joke, my roommate, Jim, gave me a copy of George Orwell’s Down and Out in London and Paris, with its classic description of what a kitchen “plongeur” did in the bowels of an expensive hotel restaurant in Paris. My kitchen job at the Hardin House did not compare to Orwell’s experiences, but there were several times I was down on my knees cleaning out the grease trap under the sink and removing clogged food from the disposal so it could start working again. Unlike the “plongeurs,” we Hardin House kitchen workers had a fancy dish washer to help us with washing the many dirty pots and pans and dishes. Mopping up the kitchen floors was somewhat enjoyable because we knew that a delicious meal would be waiting for us after our work was done. The head cook prepared marvelous meals for the girls and staff. I can honestly say that the kitchen was relatively clean and hygienic and did not compare to the filth described by Orwell at the hotel restaurant kitchen. When it became very busy at mealtime, I was sometimes asked to serve portions of the meal to the girls. “Good evening, which entrée would you like—the roast beef or the Chicken Parmesan,” I asked with a goofy smile or at least it was a fake smile. One evening, the manager caustically remarked that these girls did not know how good they have it: “Here is one girl who asked for a full dinner plate of food, and she barely touched any of the food. What a waste.” Not realizing it was a rhetorical remark, I replied: “her parents paid good money to have their daughter live at the Hardin House and she can really do anything she wants with the food.” She glared at me and walked away. The manager often stood behind us servers, making sure that equal portions were correctly given to each girl. When all of the girls had been served and had finished their meals, the kitchen crew picked up remaining plates, cleaned the tables, and swept up any food scraps under the chairs and tables. Then we feasted on our meals at a table in the back of the kitchen. I tried secretly to sneak out a second dessert to eat later at my apartment, but I was caught by you-know-who. I was instantly fired on the spot; she got her revenge. My favorite singer, Frank Sinatra, was singing his hit song about the time of my firing: “That’s Life: You’re riding high in April, shot down in May…” After I was fired by the manager, I found another job at another rich girl’s dorm; did you really think that I would now have trouble buying my car? The kitchen student workers were allowed to sit in the main dining room at a table reserved for us lucky dishwashers, bus boys, and servers. We had to be more careful with our conduct in front of all those very attractive co-eds. My ’67 Mustang After two years of working and saving my money, I was nearing the end of my patience with not having a car. I had saved a good sum of money but was still not able to buy a new car outright. I did not want a used car. What made the difference was that I received a full scholarship for my final year of college. It paid to have excellent grades. In the 1960s, to receive the scholarship money the student had to be in good standing and show proof of enrollment. When I showed the foundation that information, I received the check. I could do whatever I wanted with the money—presumably quit my jobs and concentrate on my studies and use the money for tuition and living expenses. Instead, I used the scholarship funds with my savings to purchase outright a cool, sky blue 1967 Mustang, four on the floor—a classic if I had kept it! There was no need for monthly car payments, but I had to continue to work my two jobs to pay my living expenses, which now included gas and car insurance. I filled up the car at Shamrock’s, which gave free glasses for a full tank. I bought the car in the summer before I went back to work at the Hardin House in the fall. I was now ready to party. However, before I could start driving, Jim had to drive the car off the dealership lot because I did not have a license and did not know how to drive a manual. After a monthly ordeal of Jim teaching me how to drive, I took my driving test at the Texas Department of Safety on Lamar Avenue a couple of miles from campus. I passed on my first try. Jim and I were casual friends in high school, and because both of us were in pre-pharmacy at Texas Western College, we decided to room together in Austin to cut down on our living expenses. Unlike me, he dated a girl before I had my first date, and they soon fell in love and wanted to get married that summer. Minnie had a family in San Benito (in the South Texas Valley) and went home to tell her parents about her upcoming marriage. A few days later, Minnie asked if Jim could help her with her possessions she had at home. I was recruited to be the chauffeur and eventually the best man at their justice of the peace wedding back in Austin. The drive was about 6oo miles round trip, via US 77 S. It was my first road trip, and the Mustang performed brilliantly, all done in one day. My First Real Date Lest I forget, let me tell you about one more episode I had at the Hardin House before I was fired. Mrs. Stella Hardin allowed only sophomores and juniors to reside in her house. The parents knew that she treated their daughters as if they were her own children, and she had strict rules on their behavior while they lived in her house. A Hardin brochure stated very clearly her rules: This is my house with my rules; if you are to live here, you are to follow my rules. Mrs. Hardin was a gracious woman, a refined Southern lady. I would see her one last time near my graduation date. This last incident involved the breaking of one of Mrs. Hardin’s cardinal rules about no dating of kitchen student workers. One evening, I was able to catch the eye of a cute sophomore as she waited in the serving line to get her meal. One thing led to another, and we exchanged names. She was a much younger sophomore than the other girls, having just turned 18. Starting my fourth year of college I was the proverbial older man—I was 21. Perhaps it was due to my age and my Latin good looks (?) that she finally accepted a date with me. I think she accepted my date offer because every time I called to ask her for a date, her roommates answered the phone and made it clear that she was not in and to stop calling. She was nice to me when I saw her in the serving line, and she finally agreed to talk on the phone when I gave her my phone number. I believe her roommates dared her to go out with that unknown Mexican guy who worked in the kitchen. We agreed I would not go into the lobby of the Hardin House and ask for her to come down from her room. She suggested that we meet me outside at a specified time as if she were going alone to the library. The date was no big thing. We went to a movie at the Varsity Theater on the main drag across the street from the Texas Union. It was the Audrey Hepburn movie, Wait Until Dark, about a blind girl and drug dealers. The only time we really touched was when she jumped out of her seat and grabbed me during the classic scene when the dealers had no lights to find Hepburn in the darkness of her apartment until they opened the refrigerator door, and the room turned all bright. The whole audience screamed. We left the movie laughing and talking, and she complimented me on my new Mustang. She was waiting all evening to show me one last thing. When we arrived at the Hardin House, I walked around the car to open the door. She got out and unloosened the strap on the trench coat that she never took off during the movie and quickly flashed me that she was only wearing a shortie nightgown. She grabbed me and abruptly gave me a brief French kiss, daringly darting her tongue into my mouth for a nanosecond, and then ran to the front door. I never saw her again because it was close to finals, and I was fired shortly thereafter. I guess she won the dare with her roommates to go out with a Mexican. For some of those girls at the Hardin House, but not my particular date, I am reminded of a Beatles’ song. “Baby You’re a Rich Man: How does it feel to be one of the beautiful people?” Marking Time: My Final Year Now that I had my Mustang, I was able to have more dates after my first encounter with the Hardin girl. Actually, the first time I took out a girl in my Mustang was within a few weeks of buying the car. It was with a girl I had met at Ward’s when she came in as a customer. I would not call it an actual date because when I asked her out after work for burgers at McDonald’s, she brought her younger brother without telling me; he was in his teens and had a developmental disability. Unwisely, I let her drive my Mustang up I-35 to Round Rock and then back to Austin. We were lucky that we were not caught for speeding. Later that same night we returned to my apartment complex, which had a swimming pool; not having any swim trunks we jumped into the pool with our jeans on and sat there talking for a couple of hours. After that episode, I knew that I had to be more careful in the selection of my dates. There were a few girls who worked in the cosmetics section at the drugstore, but they had no interest in college. I had a few dates with a couple of them but there was nothing in common that kept our interest to see each other again. There were some female pharmacy students that I was able to know better, but I found out that having dates with two of them created too much gossip to endure and that ended my attempts at romance with fellow classmates. I did not try to get dates with any of those co-eds at my second job. They were older than the Hardin girls, and to be truthful I was somewhat intimidated by their snobbery and arrogance. I know what you are thinking—what about my studies? I would be lying if I said that it did not have an effect on my studies. My going out during the summer and fall semesters of my last year in pharmacy school did reduce my studying time, and for the first time I had to struggle to eke out two B’s and two A’s, after a near perfect two years of A’s in my earlier classes. UT professors posted exam grades on their office doors so everyone could see what you did on a test and what your final grade in the course was. I remember a female student, not a pharmacy student but who was in two of my science classes, asked me just out of the blue why I did not do better on one of my tests. I did not make the highest grade in my physiology class on that one exam. We really had never talked much out of class. But I aced the final exam with a 98. She did not say anything to me then. Not to stereotype people, she was a pleasant, good-looking sorority white girl who I remember dressed very preppy with cute short skirts, stockings, and expensive loafers. I did not wear my Mexican heritage on my sleeves while I was at UT, but anyone born in Texas recognizes who is Mexican and who is not. I am sure that she knew I was a Mexican. In my final semester, I made all A’s in some of the more difficult courses in the curriculum. That made up for that fall semester. I graduated first in my class. Relaxing After putting in a full day and night working and studying, my idea of relaxing and having fun was to listen to two Austin radio stations, KNOW-AM and KAZZ-FM, in the late evenings. KNOW played top 40 songs and KAZZ was the progressive station covering folk, jazz, and blues. I went to sleep listening to these stations. Most Saturday evenings after working at Ward’s, I returned to my garage apartment around 10:30 PM. A fraternity house was near my apartment, and I often heard a rock band playing and frat boys yelling and screaming during one of their Saturday parties after a Texas football game. One night a local band was particularly good, singing Van Morrison’s hit song: “And her name is G… L…O…R…I… A and I’m gonna shout it all night.” It turned out to be a blast of a party with the band singing the lyrics of “Gloria” over and over for about 10 minutes straight. I was tempted to sneak over to the frat house to see the wild orgy scene. But I had to work at Ward’s that weekend, both Saturday and Sunday, and I needed some sleep. A myth spread throughout the Texas fraternity community that the song was sung for more than 45 minutes. As I was drifting to sleep, I heard these lyrics reverberate in my mind throughout the night: “By the time I get to Phoenix she’ll be rising.” I wished that I had had a girlfriend to think about. Closer to the End Late one evening I was listening to a Paul Simon song on the radio. I know what you are thinking, and it was not that song. It was from the album of the movie, The Graduate, Mrs. Robinson. It was my final semester of pharmacy school in 1968. I had seen the movie, and it made me realize I was about to begin my real life after completing my degree at the University of Texas. There was an obnoxious guy sitting behind me at the theater who made wisecracks throughout the movie about how dumb the main character, played by Dustin Hoffman, was, and it sort of ruined the movie for me because I later learned that the asshole was a pharmacy student in one of my classes. For my final two semesters, I got up around 5:45 AM and made it to work by 6:30. KNOW AM played the Top 40 hits and it seemed to play the same hit in the morning when I was driving to work. A particular song that I heard for the last several weeks before I graduated was the one by Dionne Warwick—”Do You Know the Way to San José?” It really got to me because I was getting antsy on where I would live and whether I would work as a pharmacist or go to graduate school to earn a doctorate in pharmacology and toxicology? The Vietnam War was really heating up in 1968. My decision was made for me when the government offered draft deferments for admission into graduate school. I took the GRE, applied for fellowship support, and filled out several applications to four or five universities. Then I waited. For the last several months of the spring semester, I was content to wait it out because several of my professors had written excellent letters of reference for me and told me that I would be accepted into graduate school without any problems. However, the year 1968 was a very traumatic time in American history: the assassinations of MLK and RFK occurred; there were major race riots in several large cities; there was the resignation of LBJ because of the Vietnam War; there was the rise of the Chicano Movement; and there were massive protests at the Democratic Convention in Chicago to decide who ran in place of LBJ against Richard Nixon. I began to realize how much power and influence the Democratic Party had lost in Texas by observing those rich co-eds’ reactions to the deaths of MLK and RFK. Early in June after RFK had won the California Democratic primary over Gene McCarthy, the news of his death was being shown on TV in the lounge of the girls’ dorm I was working at. It was next to the dining hall as I walked to a table with my tray of food. I heard loud screams, laughing, and clapping by the girls at the announcement of his death. I was so glad that I was leaving UT, Austin, and Texas right after my graduation. My Future Is Decided A month before graduation, I learned that I had received a prestigious, nationally competitive fellowship from the National Science Foundation, which allowed me to use the fellowship funds to attend a university of my choosing. I soon realized that this award was something big because several of my professors were trying to persuade me to stay at Texas for my graduate work. I chose the University of Kansas on the recommendation of my favorite professor, Dr. Delgado, the only Mexican American on the faculty. I would leave Texas later in June right after I had taken my board exams in pharmacy. A few weeks before graduation, I was working a Saturday shift at Ward’s, which on that particular day there was a sale on many OTC drugs and several cosmetic products. I was working one of the registers and out of my right eye I saw Mrs. Hardin at the next register. I tried not to look at her. I thought to myself that even the rich like to buy things that save them money, even if it’s at a discount pharmacy. The interior of Ward’s was not that fancy, and all types and classes of people came into the store. The prices of each product were placed on the shelf with a piece of masking tape right below the product. This meant I had to memorize the prices of the products because there were no price stickers on the items. Anything to save money and time for Ward’s. “Young man, how are you doing with your classes?” Mrs. Hardin pleasantly smiled at me. “Quite well. I will graduate soon with a degree in pharmacy and plan to go to graduate school in Kansas.” I had only seen Mrs. Hardin in the kitchen a couple of times and never thought she’d recognize me a year later. She looked straight into my eyes and said: “Good for you and best of luck in your new studies.” I was at loss for words and simply replied, “Thank you”! She walked out of the store with her toiletries and drugs and that was the last time I saw her. Epilogue My parents, my older sister’s family with her husband and three kids, and my unmarried younger sister came to Austin to celebrate my graduation and send me off to attend graduate school at the University of Kansas. After the College of Pharmacy graduation ceremony, where I received several pharmacy textbooks for graduating at the top of my class—Summa cum Laude, I took my family back to my apartment to eat. My new roommate, Nick, and I went to Kentucky Fried Chicken and got several family meals. We ate, talked, and laughed. We also planned to attend HemisFair ’68 in San Antonio the next day after graduation. I had set up my family in a small family-run motel near campus on Guadalupe Street, the so-called “Drag.” It was not fancy, but it was inexpensive and easy to get on I-35 to go to the World’s Fair. I was to pick up my parents in my Mustang. Early Sunday morning the next day, I arrived at the motel and my father was wearing a sleeveless T-shirt getting some fresh air in the gravel-dirt parking lot outside his motel room. It was going to be a hot June day in Texas. A truck suddenly did a U-turn in the near empty street and came to a screeching halt in front of the driveway to the motel. The driver yelled from his truck: “Are you looking for work—you can make an easy $25 for a small project at a building site!” The white builder thought this Mexican man would jump to work for him that morning. My father laughed off the offer and told the man he was visiting his son in Austin. I turned my back on the man and angrily said to myself—this is Texas. The next day I said good-bye to my family and took off for Houston to take my board exams. My next stop was Kansas to begin graduate school. But that part of my life was interrupted by the cancellation of my graduate deferment, and I had to serve a two-year stint in the US Army. And then I started my PhD work in 1970 at the University of Kansas.  Dan Acosta is a Mexican American born and raised in El Paso. His grandparents emigrated to the US in the early 1900s. His career spanned 45 years as an educator, scientist, and administrator in academia and the federal government. He recently retired at age 74 in 2019 in Austin and plans to write about his experiences with discrimination and bias during his life and career. He received a B.S. degree in Pharmacy at UT-Austin and a Ph.D. in Pharmacology at the University of Kansas. He has had a few of his stories published in the Sky Island Journal, The Rush, Somos en Escrito, and The Acentos Review.

3 Comments

A una anciana Venga, madre— su rebozo arrastra telaraña negra y sus enaguas le enredan los tobillos; apoya el peso de sus años en trémulo bastón y sus manos temblorosas empujan sobre el mostrador centavos sudados. ¿Aún todavía ve, viejecita, la jara de su aguja arrastrando colores? Las flores que borda con hilazas de a tres-por-diez no se marchitan tan pronto como las hojas del tiempo. ¿Qué cosas recuerda? Su boca parece constantemente saborear los restos de años rellenos de miel. ¿Dónde están los hijos que parió? ¿Hablan ahora solamente inglés y dicen que son hispanos? Sé que un día no vendrá a pedirme que le que escoja los matices que ya no puede ver. Sé que esperaré en vano su bendición desdentada. Miraré hacia la calle polvorienta refrescada por alas de paloma hasta que un chiquillo mugroso me jale de la manga y me pregunte: — Señor, jau mach is dis? -- To an Old Woman Come, mother— your rebozo trails a black web and your hem catches on your heels, you lean the burden of your years on shaky cane, and palsied hand pushes sweat-grimed pennies on the counter. Can you still see, old woman, the darting color-trailed needle of your trade? The flowers you embroider with three-for-a-dime threads cannot fade as quickly as the leaves of time. What things do you remember? Your mouth seems to be forever tasting the residue of nectar hearted years. Where are the sons you bore? Do they speak only English now and say they’re Spanish? One day I know you will not come and ask for me to pick the colors you can no longer see. I know I’ll wait in vain for your toothless benediction. I’ll look into the dusty street made cool by pigeons’ wings until a dirty kid will nudge me and say: “Señor, how mach ees thees?” — RAFAEL JESÚS GONZÁLEZ © 2022 BY RAFAEL JESÚS GONZÁLEZ Riffs sobre el poema |

| Salimos muy temprano en la mañana y llegamos en la tarde. Había un jacal de piedra donde nos quedábamos. La casa tenía un techo de paja, pero la mitad del techo estaba caído. En la noche hacia tanto frio que habían carámbanos en las vigas y sobre las ventanas. Yo iba y cojía los carámbanos y se los traía a mamá. We’d leave [the house in Nava] very early in the morning and wouldn’t get there until well into the afternoon. There was a stone hut where we’d stay. It had a straw-thatched roof but half of it was fallen in. The nights were so cold that icicles formed on the rafters and the windows. I used to break them off and take them to mamá. |

| “Les voy a contar un cuento medio chistoso,” dijo Ventura. “Una vez cuando estaba trabajando en ----, tenía una mujer. Le dije que le iba dejar algo cuando me fuera. Cuando montante mis cosas en el caballo para irme, le dije, “Ven acá para darte tu regalo.” Cuando se acerco, le corte la cara de los dos lados con mi navaja de resurar.’ Y papá le dijo, ‘Si te atreves hacerle un mal a unos de los mios, te juro que te mato.” “¡O no, jefe!” dijo Ventura. “Nunca haría eso.” “I’m going to tell you a funny story,” said Ventura. “Once when I was working at--- (place name forgotten), I had a woman. I told her I’d give her something when I got ready to move on. When [the day came to leave and] I was done loading my horse, I told her, “Come here so I can give you your gift.” When she got close enough, I slashed both sides of her face with my razor.” Papá then said, “If you ever dare to hurt one of mine, I swear I’ll kill you.” “Oh, no, boss!” said Ventura, “I’d never do anything like that.” |

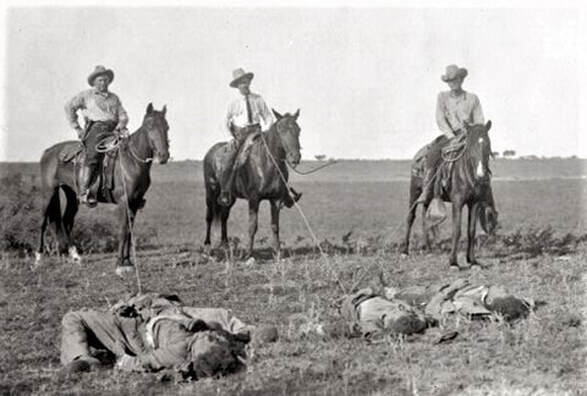

Sometime after that incident, my grandparents went out to Rosales again to bring fresh supplies to the herders. My grandfather noticed some of the animals had separated from the herd and were wandering in the horizon. He immediately set out to retrieve them, and it wasn’t long before Ventura was facing down my grandmother. My mother recalled the moment with terror, as if she were re-living that moment. She remembered his eyes, how they shifted about, a hint of a smile forming on his lips.

“Where’s the boss?” He asked my grandmother.

“Por hay anda,”my grandmother said, meaning close-by, just out of sight.

He looked around quickly. “I don’t see him.”

“He’s here,” she said self-assuredly. She, too, had grown up in desert during the time of the Revolution when young women, especially a young white woman like herself, were the target of rapacious men, revolutionaries and federales alike.

Ventura looked around again, but my grandmother’s cool steadfastness

discouraged him. He took a step back, perhaps remembering my grandfather’s willingness to use his gun. My mother said that when he stepped back, it was as if all of his weight were going forward and he had physically hit a wall. It was unmistakable what he intended to do.

Like all of the transient men of the desert, Ventura was gone not long after.

Even today, straying too far from the springs and troughs can be deadly for cattle. The cowherds guide the cattle back to the ranches or natural springs or to the water troughs. Recently, a cowherd poached some water from us for his herd. He may have been drinking and delayed guiding the cows to their water source. We weren’t mad. The few humans of the desert look out for each other. Natural law prevails for good and sometimes for evil.

Pedro Apolinar Jr., about 16 years-old

Pedro Apolinar Jr., about 16 years-old “Don’t kill me,” pleaded Pedro Jr.

“I’m not leaving a witness,” the bandit said, and he surely would have fired a shot had not one of his companions stepped in.

“Don’t kill, him. Look at him. He’s just a child.”

In what seemed an eternity, the bandit finally lowered the gun and the group departed, leaving Pedro Jr. stranded without food or transportation. Fortunately for my young uncle, the dog was cowering nearby and unseen by the bandits. Pedro Jr. carried a little notebook all the time to keep inventory and take notes for my grandfather. He tied a note for help on the dog’s collar and sent the dog back to my grandparents. My mother remembered when the dog staggered into the house, and my grandparents’ alarm upon seeing the loyal dog there alone. The police were alerted. By the time my grandfather retrieved my uncle and returned to town, the police had apprehended the bandits.

“Are these the men who robbed you?”

My uncle identified them one by one and added, “That one put the gun to my head, and this one is the one who stopped him from killing me.”

Standing under the full moon of the Nevada desert, I wonder if he sees me invading his dreams at that moment. But even in his dreams, I discover that his mind remains impenetrable. He has become like the desert that absorbed him.

Rosa Martha Villarreal, a retired Adjunct Professor at Consumnes River College in Sacramento, California, is author of several novels important to American literature, including Doctor Magdalena, The Stillness of Love and Exile, and Chronicles of Air and Dreams, and a children's book, The Adventures of Wyglaf the Wyrm. Copyright Rosa Martha Villarreal, 2017.

A Book Review of Cabañuelas, a novel by Norma Elia Cantú

Intersections:

Science, Art, Moment-to-Moment Life, and Representation

You must distinguish and then combine...

– Goethe

When we conform to binary choices, we may as well RSVP, “yes,” to an invitation not to think. Black or White, Right or Left, Science or Religion, Pink or Blue—these “boxes” may provide a haven for those who enjoy the comfort of lines not to be crossed, but they offer no visionary or revisionary way to see the world, and how to navigate through that world with an open mind and heart. A binary world is one filled with assumptions that in most cases turn out to be wrong.

Societal constraints impact our career and/or vocational directions too. How much independent thinking do we afford our children? How much do we tell them that learning is not limited to a classroom; it can and should happen everywhere. I was fortunate to have been mentored by amazing thinkers who taught me to always seize on an opportunity to learn. I heeded their advice, and together with luck and hard work, I was able to shape a career that did not keep me confined on one path. I have forged a career in immunology as an academic scientist, and have completed many written works as a fiction and non-fiction author. Whether in science or art, all of my work is informed and guided by social and political landscapes that intersect and enrich each other.

In the courses I teach, such as cell and molecular biology, I found it impossible to lecture about mutations, or changes in our genetic blueprint, without ensuring students understood that human diversity, in large measure, is a consequence of these changes. Differences in skin pigmentation, hair and eye color, and so much more, are due to alterations in our DNA. Variations due to changes in our genetic blueprint also impact sex development, as seen in intersex people. The frequency of intersex in the population is approximately 1-2%. Intersex people are born with internal reproductive anatomy and/or external sexual anatomy that differ from typical males and females. We have been taught to think that those in possession of a vagina, clitoris, ovaries, and XX chromosomes = female, and those in possession of a penis, testes, and XY chromosomes = male. However, this is not the case for everyone.

The strength of binary thinking tries to force us into one of two “boxes,” and has limited our ability to accept and welcome intersex people. Designating intersex people as unequal and inferior to males or females has led to the unjust treatment of those with intersex variances. If a child is born intersex and is in possession of external genitalia that is androgynous, a mix of male and female, the child may be subjected to surgeries aimed at “correcting” the “imperfections.” In most cases, these types of surgeries are medically unnecessary, and are solely executed to force people to fit the sex binary.

Surgeries done purely to adhere to social norms need to be called out for what they are, nothing short of Intersex Genital Mutilation. As a biologist it has been important for me to do what I can, through writing and lecture, to utilize science in the pursuit of social justice. In collaboration with the author, intersex activist, and consultant, Hida Viloria, we have written a book (anticipated publication date, early 2020) entitled, Reimagining Sex and Gender: Understanding Biological Diversity. The book not only provides the framework to understand how intersex variances arise, it also addresses how sex and gender intersect and impact policy and law, such as marriage rights.

A few years back it became clear to me that the acceptance of intersex people as a legitimate third sex could also be helpful in securing marriage equality rights. For example, viewing marriage as a right that should only be afforded between one man and one woman, does not take into consideration people who do not fit the binary. As a counterpoint to this view, I was driven to use science to write the first biology-based amicus brief in support of marriage equality to the Supreme Court of the United States. I used the natural existence of intersex variances to formulate my argument.

As with my science based writing, my work in fiction has been used to create characters and plots to call out injustice. In my crime dramas, Pig Behind The Bear and The Water of Life Remains in the Dead, I had to create a new heroine because heroes like Superman have not been interested in coming to East LA where the people impacted in my stories live. Therefore, a protagonist, a feisty Chicana by the name of Alejandra Marisol, had to be fashioned to fight injustice and protect the most vulnerable among us—immigrants and their children.

Alejandra is not faster than a speeding bullet, or more powerful than a locomotive—she can’t even leap tall buildings, but she is determined to come out on top even when confronted with bone chilling danger. She is the best in each of us. She is the dreamer, the fighter, the one where the words, si se puede or yes we can, are not enough. Instead she lives by the words, si lo haremos, or yes we will.

For me it has never been a question of how to navigate work in science and art, but rather, how could I not.

| Maria Nieto, who earned her doctorate in Immunology from UC Berkeley in 1989, is a Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at California State University, East Bay in Hayward, California, where she has been involved in underrepresented minority recruitment, teaching, writing, and research for over 30 years. Her award-winning crime novels, which incorporate her scientific insights, Pig Behind the Bear and The Water of Life Remains in the Dead, have been featured in Somos en escrito Magazine. |

Chicano Confidential

On Understanding the Situatedness

of Everyday Life While Facing

a New Year (2019)

Recently, someone turned to me and said, “You’ve got a lot going on in your life right now, don’t you?” and in a micro-second of reflection I thought, “Not any more than normal,” and then the reality of my situatedness of daily life sunk in. “Yes,” I thought, “I guess I do have a lot going on.” By this coming June, I will have 8 grandchildren (including a set of twins), as everyone is pregnant (we currently have 4 male grandchildren).

I am currently searching for solutions to place my father in long-term rehab care in San Diego and my mother’s dementia is progressing so rapidly that I can hand her something and she will place it immediately in the proverbial Black Hole. I am leading a major policy shift at my university, while acting as lead academic planner for our University’s 25th anniversary, and I have made arrangements to take our entire family to Maui for the greater part of the summer, oy vey!

I’ve even reached a point where I conducted the preliminary math demonstrating that I may be retiring as early as this summer. These events were for the most part not unexpected as I am an old scuba diver and I always “plan my dive and dive my plan,” but I have to confess: no matter how prepared one is, Father Time has a way of sneaking up on you and tapping you on the shoulder. It seems that time, numbers and my personal philosophy make up the mainstay of how I construct my reality in daily life at least for the onset of this coming year.

I didn’t think my goings-on were observable, nobody ever really does, that is, until somebody does make the observation, “You really have a lot going on right now, don’t you?” We all believe that most people don’t really care about who we are or what we stand for, not really, for emotional and practical purposes.

Daily life is way too complex for one to keep up with the energy it takes to truly care for others. I mean, doesn’t everybody always have a lot going on? It’s simply too much to keep track of what people are doing, thinking or facing. Why should my situatedness stand out, why now? Conversely, this is why I find most everyone quite interesting, everyone has a story, and every story is unique and in turn interesting. Said differently, everything may in fact be observable but what is interesting for the day or even for the moment is a topic of social inquiry all on its own; it is phenomenological in this way.

It’s as though my Self (in a social psychological sense) is evolving with every social interaction; how can it be perceived any other way? While I am keenly aware of such evolution, I’ve never felt the evolution of Self the way I do now. What better way to measure one’s situatedness than to compare your time (like, your time left on this earth) against the backdrop of the endless situations that come up in everyday life? Everything is quantifiable such as the number of strokes of genius, impulses, how many grandchildren, even the number of heartbeats in one’s life, you can count them all.

Again, the statement directed to me can be directed to you: “You’ve got a lot going on in your life right now, don’t you?” At first, it can only be examined existentially because it evokes feelings, often deep feelings depending on the situation at hand. I will say there are markers along the way, some outright signs along the way you might say that are not only directive, but, all at once full of symbolic meanings. Much like the radical empiricist William James, my tendencies are to ground what I say theoretically in observable examples, including those found in my own life.

At the onset of this past summer, I observed two massive (I mean massive) chunks of glacier each the size of five football fields slip into Glacier Bay, and this occurred within 12 minutes of each other. I video-taped the second slide, but haven’t mustered up the courage to view it again as it really rocked my world. Having been taken by surprise, I was all at once mortified to the core of my being, my brute being that is, I honestly still can’t seem to shake the feeling.

I wasn’t fearful of a tidal wave effect or anything of that sort, frankly I didn’t know what it was I was feeling. It wasn’t until weeks later that I came to the realization that I was in shock and this triggered my sensibilities beyond my control all at once, changing my human condition, forever. Likened to Ludwig Wittgenstein’s “white sheet flashes” to massive sheets of sliding ice were simply too much to handle all at once.

How else can I say it except that “It scared the hell out of me!” I wasn’t aware of the full impact it had on my psyche until much later. It was as though I was completely caught off guard by a sensation so overwhelming my sensibilities were shut down by natural defense mechanisms and as a result, I switched to autopilot, not allowing myself to feel the sensations that were so overwhelming. It was one of the greatest contradictions of my life.

While I have always enjoyed living and dwelling in contradictions, suspended existentially so, enjoying being at the helm of a sailboat with a broken rudder in a full gale storm, this was a test of the tempest, “nor'easter” you might say. I imagined the sky ripped open by a giant Russian god-like philosopher, yelling down to all of humanity:

“You all have ruined the earth; look at her now look, at Gaia (Mother Earth). The massive sheets of ice slipping into Glacier Bay are her tears crying to let her loose, to let her heal herself the way only she can do. You (humanity) need to step aside and let nature (Mother Earth) take over and heal herself, she has taken care of herself for billions of years, well before humans arrived, for Christ’s sake step aside!”

This was it! This was the penultimate contradiction of my life and it caught me off guard, I’ve been sensing this ever since witnessing Gaia cry; it was like Mary, Mother of God, crying for her son and for our sins.

Last month, in my capacity as the keynote speaker and a Distinguished Alum at UC San Diego’s 50th year celebration of its graduate division, I presented myself as a well-trained scientist that had tried on various rationales that might help me mask the realities we are facing in American society today – one is global warming. I argued that during current times it is quite difficult to perform critical objective scientific analysis because the average person on the street does not understand science and their thoughts are based on what they gather from quip-like political remarks they hear on television, on the radio or read in pop-ups that are not scientifically based.

The physical condition of Mother Earth is in the back of my mind, even more so than is the fate of humanity, she needs real help beyond what I have to offer and I have offered more valiant efforts than most as evidenced by my work in convening world-class scientists in Big Sur. At the core of my being, I’m keenly aware that everyone tacitly knows but doesn’t want to say out loud the unspeakable truth:

“We [humanity] have systematically ruined the earth due to greed and to self-preservation beyond the type designed for us by nature. We somehow got off track and at the cost of forsaking others or even contributing to the social good have designed distractions into our realities so great that we consume much more than we can play out in useful ways in one lifetime. This behavior has driven humanity far beyond the tipping point for any possibility of ecological reconstruction. There is no going back; the massive chunks of ice falling by the minute in Glacier Bay don’t suddenly re-attach themselves, they don’t grow anew like frozen crystals, they simply melt away like islands of meaning that only few can understand, because people don’t take the time or have the time to save them or Mother Earth.”

People remain distracted seeking refuge in the Google-god thinking they have an understanding of every situation, every problem and every subject matter. From a scientific perspective, it’s simply annoying to constantly hear interpretations of a Google sort from those who have little understanding of deep levels of predication. “Just Google it,” they say, with no understanding that the rhythm of their personal algorithm shines only a subjective light that cannot (will not) allow for objective truths.

The philosopher Aristotle believed that “seeing is believing” although he didn’t live in a world of social media in the same manner as we do today. He did not take into account that for political reasons people would begin purposefully altering video and pictures for political reasons. This was not part of his awareness. Said differently, whether you believe in global warming or not, whether you practice science or fake science or fake news, I know what I saw and experienced in watching Gaia cry sheets of ice.

This truth cannot be denied, I heard it, I saw it, I even smelt it. It’s like listening to your aged mother who is hard of hearing trying to order her prescriptions over the phone: “Can you please speak up,” she says. “I can’t hear you, please speak up.” It’s a truth you can’t deny, it’s not “fake,” just as in the gym, the barbells don’t lie—they are in fact heavy. Sir Issac Newton observed a basic truth “What goes up must come down.” Watch video replays of when you were young as they capture a picturesque younger Self about the way things once were and sometimes these are difficult to watch because they capture a truism: “You are [today] what you once were [yesteryear]. The unforgettable sound of cracking ice is so memorable; it is in fact plaguing to my senses, I will never forget the sound and yet this phenomenon becomes the mainstay marker for the rest of my life, placing me on a hermeneutic spiral to enjoy in a rather disturbing way.

For me the sound or old reflections are evocative, poignant even melancholy; they linger and contribute to the way I construct my reality in daily life – how else can I say it, except to say it the way it feels, this becomes my situatedness, this becomes the foundational springboard for the evolution of my Self (in a social psychological sense).

So in this way, yes, I am just like you, I do have a lot going on in my life, for many it appears I am preoccupied with the end of the end of things: objects, relationships, even perspectives or paradigms for looking at scientific discoveries. Things change, science changes the way we view realities through scientific discovery not through “fake news” or “fake truths.”

It’s the eve of yet another year to come and a year gone by even at a more precipitous pace than the previous one. Yes, I sound like my parents and uncles who constantly remind me, “Life is short.” Yet I remain baffled at what is inevitably to come, this year, unknown yet seemingly felt in my soul. What new vulgar circumstances (even rollicking vulgarity or playful exuberance) will give birth to my story writing for example?

As I grow older, words, it seems, sit on ideas with uncanny ease and make more stories seem inevitable, I never know what is coming out of my imagination next. I do however remain convinced that as Einstein puts it, “Imagination is more important than knowledge,” which, by the way, is the trick for scoring at the highest levels of IQ tests and college entrance exams. “Teach your children well.” Now headed for quasi-retirement, the fictional stories I started writing in the form of “science friction” afford me a separate life, a “separate reality” as my old friend Carlos Castaneda used to put it, and new relations.

I’m aware of my lack of formal training in creative writing, yet it actually becomes the very reason whenever I go to contemplate a “creative” work for pleasure. I’m fine with the fact that my stories will surely not be on the Best Seller’s List nor a Pulitzer Prize winner for these authors always lack soul and only write for the prize. They are in fact creatively boring, what one might typify as “tragicomic solipsism.” Frankly, I’m always fascinated at how boring prize-winning authors can be in real-life. Even so, there is almost no one I can call for honest advice, “Your stories are great” they say, with no proof or affirmation. It’s not difficult to realize how I cause a new deviance disavowal because I know they didn’t read my writings, yet feel the need to tell me they did, hey, no problem.

I firmly believe people trained in creative writing practice linguistic calisthenics; a lot of words, without soul. I understand how the book writing world works, people simply prefer living the illusion, and again, perception becomes everything; therein lies the organic disconnect. In this spirit, I have even come to believe in the “fish stories” I have to some extent imagined and I see this as a good thing inasmuch as I have continued mindful activities and exercises that contribute to the evolution of my prodigious memory that allows me to recite my finished stories verbatim. I became aware of this ability many years ago when seated in a hot-tub next to a distant relative at a family reunion held at the Rosarito Beach Hotel. I told her the story of how I was once attacked by a wild-boar on Catalina Island and she did not believe me until the next day when we were joined by her husband whom I shared the story with as well and she observed, “Sonny Boy (my nickname), I didn’t believe you yesterday but I do believe you today because you told the story in the same way word-for-word.”

It is the case that I practice the art and science of writing like I talk and talking like I write, plus I want to defer atrophy of my brain as long as possible. Most people don’t see the insight my stories can bring as they say, “his silly little stories;” they are all psychoanalytic and often viewed as “irritatingly clever.” I think more about the future and the future I am already starting to miss. I remain eager to see how my personal buoyancy plays out in a hopefully different economic and emotional climate as I reach my later years. The way I see it, psychologically I should be happy, financially I should be set. Don’t forget, a scuba diver “plans his dive and dives his plan,” so I have a plan.

But will an unexpected “four-alarm fire” surprise me, will I find it exhilarating (like being shot at), will I have the capacity to turn a nightmare into an insidious experience, at the very least a cheap thrill. If anything, my trained anticipation of the unexpected has always turned to a mission of good times. I expect to look back at any “urgency” and think “courage, after all, wants to laugh.” You can’t take life too seriously as it wasn’t meant to be that way, yet so many of us cannot see it any other way as evidenced by people who take themselves too seriously.

It is for this reason I continue to amuse myself to death. I’m having a hell of a good time, by design. Life is for me an intellectual game. The allusion and/or insinuation endorses my serious refusal to be serious. I see every idea as inescapable from the link to the evolution of SELF, not vain, not self-defeating, not even a linguistic construct, but artistic. It is through this paradigm for looking at storytelling that I simply want to show those who indulge in my stories how to live a fulfilled and meaningful life and to become less alone inside in a world with inescapable ways of contributing to alienation, Karl Marx’s greatest fear.

Said differently, through my stories I want to help people feel life, and remain more than arm’s distance from being-bored-of-being-bored. Hence, if you are going to mistake your wife for something mistake her for a hat, a nice black hat (a la Oliver Sacks) and enjoy it, don’t get freaked out by the experience. It’s like taking LSD. Timothy Leary use to say, “Never have a bad trip, learn from it, enjoy it as you will never forget what you learned.” What I believe is that there can be optimism within one’s personal despair, elation of a curious sort in its anomie. More than ever I feel like a paradoxical character with an outsized passion, repression and expression: twin causes of complication, harmony and disharmony with significant others who think:

“He is such a nice person, a good father and great grandfather, yet there is something in him that keeps him from being completely decent.”

I have to ask, “Do people not understand my aesthetic?” Years ago I wrote a book on fear and it wasn’t until now that I came to the realization that I write stories because I am afraid that the last thing I will write will be the last thing that I write. This is not paranoia as that would be fear of the unreal; my fear is based not only on real fear as evidenced by the stories I keep producing, but also by the body of original scientific knowledge I have contributed over time. I find in life amusing peculiarities that trigger epiphanies, continually!

Maybe deep down inside there is the possibility that telling a story could lead to redemption of a sort, for what reason, I am searching, but perhaps it may be found in spirituality and values. So, this is what is on my mind on the eve of a new year.

I’m curious to know what’s on your mind.

Archives

June 2024

April 2024

February 2024

November 2023

October 2023

January 2023

December 2022

October 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

March 2022

February 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

June 2021

April 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

October 2019

August 2019

July 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

March 2017

December 2016

September 2016

September 2015

October 2013

February 2010

Categories

All

2018 WorldCon

American Indians

Anthology

Archive

A Writer's Life

Barrio

Beauty

Bilingüe

Bi Nacionalidad

Bi-nacionalidad

Border

Boricua

California

Calo

Cesar Chavez

Chicanismo

Chicano

Chicano Art

Chicano/a/x/e

Chicano Confidential

Chicano Literature

Chicano Movement

Chile

Christmas

Civil RIghts

Collective Memory

Colonialism

Column

Commentary

Creative Writing

Cuba

Cuban American

Cuento

Cultura

Culture

Current Events

Dominican American

Ecology

Editorial

Education

English

Español

Essay

Eulogy

Excerpt

Extrafiction

Extra Fiction

Family

Gangs

Gender

Global Warming

Guest Viewpoint

History

Holiday

Human Rights

Humor

Idenity

Identity

Immigration

Indigenous

Interview

La Frontera

Language

La Pluma Y El Corazón

Latin America

Latino Literature

Latino Sci-Fi

La Virgen De Guadalupe

Literary Press

Literatura

Low Rider

Maduros

Malinche

Memoir

Memoria

Mental Health

Mestizaje

Mexican American

Mexican Americans

Mexico

Migration

Movie

Murals

Music

Mythology

New Mexico

New Writer

Novel

Obituary

Our Other Voices

Peru/Peruvian Diaspora

Philosophy

Poesia

Poesia Politica

Poetry

Politics

Puerto Rican Diaspora

Puerto Rico

Race

Reprint

Review

Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales

Romance

Science

Sci Fi

Sci-Fi

Short Stories

Short Story

Social Justice

Social Psychology

Sonny Boy Arias

South America

South Texas

Spain

Spanish And English

Special Feature

Speculative Fiction

Tertullian’s Corner

Texas

To Tell The Whole Truth

Trauma

Treaty Of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Walt Whitman

War

Welcome To My Worlds

William Carlos Williams

Women

Writing

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed