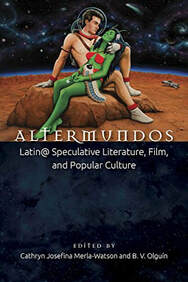

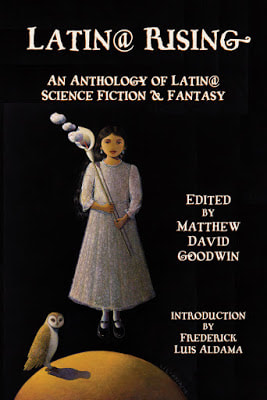

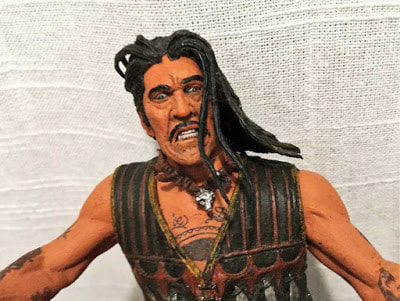

Charge up your dilithium crystals!  By Scott Duncan-Fernandez Any brand spanking new robot may require batteries. For a first of its kind book to package literary, media, and cultural criticism about Latino speculative fiction, Altermundos would generate much more of a charge with some knowledge of Chicano Studies and issues. Most importantly, though, Altermundos elevates a genre to its worthy place of criticism, which has been ignored as low culture or critiqued (or, disdained) as art despite its speculative roots. While Altermundos calls itself and at times adheres to “Latino sci-fi,” it sticks mostly with us Chicanos, and of course, mostly speculative works: Chicanofuturism, Chicano sci-fi, and Chicano literature and culture. Not only does Altermundos give a fresh look at some classic Chicano work with a new speculative lens, it brings forward many works of Latino sci-fi, fantasy, and horror that have been in the periphery. Latin@ Rising (Wings Press, 2017), (reviewed here in Somos en escrito, under the title, “¿Qué hay en la bolsa?”) gave us a look at the present and future of US Latino speculative fiction; Altermundos validates our past and with its many essays discussing issues ranging from feminist, queer, social, post-colonial and social justice gives us a future to look forward to. Since I began this review earlier in 2018 and set it down, there have been many Latin Scifi happenings, here on Somos en escrito as well. The Mexicanx Collective has…collected into a group of Mexican sci-fi writers. Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Machado is being made into a movie. The second volume of Latin@ Rising, now called The Latinx Archives, and a new printing of the original is in the works. (I have a couple of flash stories that will be included there). The Extra-fiction contest at Somos en escrito had its first winner in Rudy Ch. Garcia and received many other fine work with an extra something. I keep seeing more and more sci-fi flavored (some a pinch, some a cup) novels and stories by our communities floating up from the depths of the periphery. Batteries required for those not up to light-speed. I love reading literary criticism and especially those works dealing with US Latino and speculative fiction, so of course, I’m right in the crux of the demographic of their audience. That said, I’m concerned that those who like literary criticism in general won’t take this as seriously because it deals with speculative works. The fact is that this book enhances and reinvigorates Chicano literary analysis. This is a fresh onda bigger and better than the one my fellow Texan ran away from so quickly in that mess of a movie, Interstellar. Altermundos is 80 percent literary/media criticism, 10 percent personal essay, and 10 percent fiction or poetry. Like literary fiction and poetry, literary criticism is a discussion and it’s a bit difficult to jump in and nod like you know what’s going on. While many may be up to speed, for those interested in sci-fi and lack a basis in Chicanismo, they may need a little help. If you are in the opposite camp, you may find, as Altermundos makes a case for, sci-fi elements floating in the pozole of Mexican American literature. An important work to know in general and for the criticism presented often in Altermundos is Borderlands by Gloria Anzaldúa. Quotes from it are spread throughout, as well as quotes from her interviews. Her book opens its arms to mestizaje, and advocates for a new kind of mestizo-mindedness that includes gender as well, which comes up in many Altermundos essays. Anzaldúa clearly applies Post-Colonial and Queer theories in terms of identity and mestizaje to the crossroad of selfhoods that our experience entails. Another book is Chicano Manifesto. While not discussed in Altermundos, it remains to this day the best book to know issues of Chicano society, history, and identity, and one many other books build upon. (Disclosure: our own editor, Armando Rendón is the author.) Many books offer a background on Chicano literary theory, including Chicano literature itself. The two overlap more in the Chicano realm than in the standard American realm as they often deal with issues of identity and history, Drink Cultura by Jose Antonio Burciaga, for an example. Yet,Borderlands and Chicano Manifesto are the ones to help anyone get up to speed forAltermundos. A few terms of note Altermundos: Spaces, grounded in realities that look toward utopian and decolonial futures. Alter-native: an outlook with Neo-Native eyes. Rascuache/Rasquache: You know what it is if you’re a Mexican American. It’s your grandparents’ back yard full of recycled and repurposed and redecorated objects. It’s what happens when teenage boys in the 50s see Anglo teens get new cars and then fix up their own lemons with style into ranflas. It’s doing a lot with a little and with style. It’s mentioned every other word in nearly every essay: this pocho will never forget rascuache again. CSP: Chicano Speculative Production. Something made by a Chicano and speculative in whatever media. Chicanafuturism: Inspired by Afrofuturism, it’s the way the use of technology transforms Chicano life and culture. While Afrofuturism often deals with diaspora, Chicanafuturism often deals with the post-colonial. Nepantla: Nahuatl word meaning “in the middle,” being caught between the dominant culture and one’s state of origin, which is used to connote the state of in-between in the Chicano experience. Nepantlera: Portmanteaux of the Nahuatl word nepantla and Spanish -era, someone who exists in Nepantla. Praxis: implementing ideas or theories. An important concern for social justice. Chicanonautica: A Chicano speculative traveler that trespasses to new frontiers. A term coined by the father of Chicano sci-fi, Ernest Hogan. Selections of Work Many Chicano Speculative Productions lie on the periphery, but a few pieces reviewed are more fringe than others. I expected the movie Paranormal Activity: The Marked Ones with its Chicano Hardy Boys and Nancy Drews taken over by the demons they investigate to make an appearance or have a mention. I look it up and the only thing Latin about the movie were its actors and setting. When it comes to films, this calls into questions what is a CSP, as often films taken or marketed as CSPs are Anglo written, produced, and directed by non Mexican Americans. The much beloved and recent Coco is in that category. We are not always the ones defining our very existence. It seems Altermundos has chosen movies with Latin directors such as Machete and Sleep Dealer and avoided movies that may not exactly fit the bill. Some of the story choices for review are somewhat recondite. Finding “Refugio,” for example, took a little searching. It’s a short story included in Night Bites: Vampire Stories by Women Tales of Blood and Lust (1996). It isn’t listed under the work on the author’s site and the Amazon page doesn’t list her name as included in the anthology. Granted, it took me ten minutes rather than ten seconds, but in this information age, that’s an eternity. “Refugio” is an excellent story, recondite or not, and I’m glad to have been introduced to Terri de la Pena’s work. This kind of thing, the finding of interesting work new to you, is what anthologies are about. List of works that come up often throughout Altermundos: Sleep Dealer Alex Rivera, film Love and Rockets Jaime Hernandez, comic Los Vendidos (the sellouts) Luis Valdez, play Lunar Braceros Rosaura Sanchez and Beatrice Pita, novel Smoking Mirror Blues Ernest Hogan, novel The Ragdoll Plagues Alejandro Morales, novel The work of Guillermo Gómez-Peña The work of Gloria Anzaldúa  Serendipity in the periphery After finding and reading/viewing/listening to most of the work critiqued or mentioned inAltermundos (I had read a few before and a few others had been on my radar), I found that many of these works come from the periphery. Though sci-fi and fantasy are booming—just look at how superhero movies have become big blockbusters rather than underfunded or fan made over the last two decades--our Latino works are still ignored, pushing in at the corners, or thought of as lessor, especially the Mexican American, southwest variety. Reading these fine works, which are somewhat forgotten or hidden, is distressing: The Ragdoll Plagues has great prose. Smoking Mirror Blues is like Neuromancer or Strange Days got lowered and fitted with hydraulics and a paint job of an Aztec temple on its hood. In other words, something well written and fresh that should have been a movie by now. These and the other works in Altermundos are deserving of the critical storms that they can weather. Like the quantum telescope, the critical eye of scholars changes them: it elevates the Chicano Speculative Projects and brings them into much needed attention. It’s about time. We Latinos need these stories where we are not the villain. Where our eyes are not forced to participate in a ritual that reinforces our subjugation and the view of ourselves as monstrous natives, mestizos, afro-mestizos, or rival Spaniards. CSPs are not Avatar or Alien Covenant. That is, our stories don’t portray obvious retellings of westward invasion to achieve dominance over everything to tell us who we are. We are the actors and we are humans in these works, and sometimes more than human.  Retconning Many essays aim to recast or “retcon” all of Chicano literature as a speculative production. I agree…mostly. Like any idea, it fits here and not there. Like Ernest Hogan says, “…Chicano is a science fiction state of being.” We are mixed, we don’t fit in a culture that throws aspects of the monstrous upon us. This causes many CSPs to ask, “¿Oye, what kind of mutant are you?” This does give a new, refreshing point of view, but it’s also something that may be over applied. Imagination and the imagination of belonging may be speculative, but is Jane Eyrespeculative? I know that’s an old British book and not Mexican American, but it’s one where a female character imagines (literally in some places) her identity and a world in which she can have more agency. Many Chicano literary works and media also seem to deal with pure, uncut reality and sometimes they point to a future of inter-reliance and over-coming that isn’t here yet, something that isn’t always super-duper speculative. In other words, don’t get no F on su tarea, kids, for saying The Squatter and The Don is puro sci-fi. Speculative isn’t always robots, zombies, and aliens, but there is a little over-reaching here. Some Highlights “Poison Men: A Chicana Vampire Tale” Provided as an example of what a feminist Chicana vampire tale can be, Linda Heidenreich includes this original work in the essay “Colonial Past, Utopian Futures.” It’s the first time I’ve seen fiction about Josepha, the woman who was the first recorded Chicana lynched in California under US rule. Josepha killed a man who violently broke into her and her boyfriend’s home. The lynch mob hanged her and her last words were to ask that her body be given to her friends. Josepha has been mentioned in passing in histories, often incorrectly and dismissively as Juana. In the story, Heidenreich offers that Josepha is a vampire. Healed after her hanging, she finds a cabal of older vampires to learn from, to spend centuries on learning. Heidenreich argues for a better kind of vampire tale, a tale of sexualized other that doesn’t have to end in a type of control—marriage, death, or sexual passivity. A point and example for all of us to ponder, especially us straight male writers about our portrayals. I love this salvaging and empowering of our stories and historical figures. Machete Yes, Machete gets his own section. Essays on Machete could have taken up the entire book, but he only gets one. Danny Trejo’s cool character (I’m not a fan obviously) brings much together: resistance, folk traditions, and science-fiction. The topic discussed toward the end I found the most interesting: How Machete inhabits a folk hero position (in a “whatever works” manner) and how like the corridos of old, such as those of Juan Cortina, Joaquin Murrieta, and Tiburcio Vasquez, he unifies voices of Mexican American identity and resistance. I might even add, camp. Chicanos are nothing if not humorous, and humor is a great weapon against naked emperors. “For those seeking signs of intelligent life” by Deborah Kueztzpal Vasquez An enjoyable short story (memoir?) where the narrator shares her intergalactic origins and upbringing via her mothers. As a boy, I, too, heard how my sister and I were star people from our mother; at times we believed and other times we laughed. The narrator takes a trip to the motherland in the sky and how we all can be there if we erase hate and materialism from our hearts and how governments have twisted extraterrestrial knowledge and how we can do better if…. I like that Altermundos includes a few fiction pieces. In “For Those Seeking Signs of Intelligent Life,” there is social critique, a new-old way of being, a method to resolve trauma and to see the world. Not only a good story, but something that exemplifies the many purposes CSPs may bring to the table on critiques and necessary information to living one’s life as an indigenous person and/or a person inhabiting many crossroads of ethnicity, nations, and gender. The author’s artwork is likewise excellent and adds to the story and allows the viewer to wonder out on their own personal rocket ship to the space gods. “Strange Leaves” is an excellent story – it’s being described as horror caused me to question what horror is. I would classify it as a crime-thriller as it deals with a character coming across a victim of assault while crossing over into Texas, the “strange leaves” are the victim’s clothes on a bush. Body-horror and the use of technology make me wonder, does horror have to have an element of the supernatural, as I normally view it? Whatever you may call it, it’s a good story that brings attention to an important issue of assault of innocent women crossing over. “Chicanonautica Manifesto” by Ernest Hogan Ernest Hogan, his own work often the subject of critique in Altermundos, puts many of the ideas expressed in the other essays succinctly, informally, and wonderfully. “Probably because Chicano is a science fiction state of being. We exist between cultures, and our existence creates new cultures: rasquache mash-ups of what we experience across borders and in barrios all over the planet. We mestizos have no sense of cultural purity. Mariachis on Mars? Seems natural to me.” Speaking of personal essays, “Flying Saucers in the Barrio,” which is about the Speculative Rock opera put on by high school Chicanos in the 70s, recounted by the teacher, Gregg Barrios, who wrote the play, is an amazing piece of history. The play is inspired and includes the music of David Bowie albums such as The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. In the play, the Starman, the “alien” as a Chicano doesn’t fit and isn’t welcome. The essay is an interesting and well written bit of reflection on early speculative Chicano work and a snapshot of a moment in the Chicano Movement. Los Planes de Alterlandias (ala Plan de Santa Barbara, de Aztlan, etc.) Most Chicano work, literature and media give tools for life or validation. Often include poetry, resolving of identity, social critique, and a view or a plan. Some essays in Altermundosoffer plans and a list to ways forward. Others, like the short story, “For those seeking signs of intelligent life,” offer an example of what could be, a speculative existence you could live now if you tried. This is the vision of a human, Chicano-centered space that many of the works critiqued in Altermundos get at. A science-fiction of our own personhood that may be the future, ret-conned past, or the now. The plans, the lists of concerns, the call to actions, all are speculative. They are speculative praxis, they are meant to be implemented to create a future or a future self. Several Altermundosarticles have plans for social justice, e.g., “Decolonizing the Future Today: Speculative Testimonios and Neplantlerx Futurism in Student Activism,” by Natalia Deeb-Sossa and Susy J. Zepeda. Chicano CSPs are formative and speculative. I said this first book of Latino Speculative Criticism is necessary…because we can discover and look deeply at how we portray the world in which we are human. To see how necessary this is, you don’t need to go farther than my desk: I’m only a little ashamed to say I have desk toys. Many people are familiar with the issues for Mexican American children have in the US finding positive representation in media. Being a non-fluent Spanglish speaker I’ve always been acutely aware of any brown representation in the mainstream of US science fiction, especially as a child. While it is common for the man-children of my generation to collect figurines and toys from science fiction and fantasy, I realized when I collected Mexican action figures that it was filling an old gap from childhood. While not a creative act per se, collecting figures is, as the many authors in Altermundos put it, something I can look over and imagine a world where we are human. In short, Altermundos is an excellent selection of criticism that would allow anyone to know the Mexican American experience better, but there needs to be Altermundos Dos and anAltermundos Planetas de Jovenes. We need more anthologies and more venues.  Scott Russell Duncan, a.k.a. Scott Duncan-Fernandez, recently completed The Ramona Diary of SRD, a memoir of growing up Chicano-Anglo and a fantastical tour reclaiming the myths of Spanish California. Scott’s fiction involves the mythic, the surreal, the abstract, in other words, the weird. Scott received his MFA from Mills College in Oakland, California where he now lives and writes. He is an assistant editor at Somos en escrito. See more about his work and publications on Scott’s website scottrussellduncan.com.

0 Comments

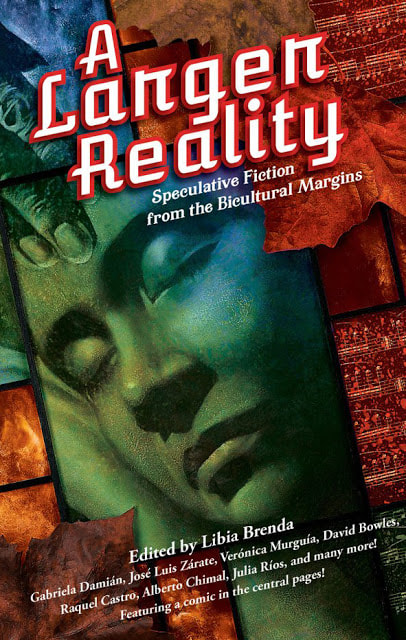

Sí, ¿Como no? We call it ¡Sai-fai! Review-Reseña en/in English y/ and Spanish, of/de: A Wider Reality: Speculative Fiction from the Bicultural Margins. Una realidad más amplia: Historias desde la periferia bicultural/ Edited by Libia Brenda Castro Rojano. Mexico: Cúmulo de Tesla, 2018 By Cristóbal Garza Several authors and translators from the United States and from Mexico join their pens —or rather, their keyboards— in this collection of short stories edited by writer Libia Brenda Castro Rojano, who also contributed with a short story of her own. This collective work was inspired by the presence of John Picacio’s Mexicanx Initiative in the 2018 Worldcon Literary Convention (Tobin). The electronic version has been distributed free online and the printed version sold out soon after its release. Each piece appears in its original language and translated either from Spanish to English or vice versa. This double format serves as an apt frame for texts that imagine post-apocalyptic worlds, simultaneous realities, and alternative universes. These stories take us to liminal areas that surround walls, portals, entrances and exits and everything that can be preceded by the prefix “bi”: bicultural, bisexual, bilingual, binational, bilateral, bifocal, and so on. The collection shows us how binary categories collapse; the inside and the outside, the human and the monstrous, the lyrical and the graphic, the humorous and the terrifying, the future and the past, the you and the me, fantasy and realism become entangled. The borders identified, enforced, traversed, and challenged here are not new, but the articulation and disintegration that the authors of Una realidad/A Wider Reality narrate are urgent and timely. Zombies, magicians, scientists, gypsies, cholos, translators, chupacabras, soldiers, superheroes, time travelers, dancers and baristas populate realities that have been bifurcated by violence but rejoined by imagination.  In the forward, Castro Rojano explains that this volume’s purpose is establishing dialogues and friendships among writers and readers of both countries. “Fences” by José Luis Zárate revolves around a magician who, after having lived on the margins of society and reality, must go beyond a real and symbolic wall to “go back to” who he really isn’t. In “Aztlán liberated,” David Bowles tells us the story of a gang of misfits who furiously fight predators to save the two countries that rejected them for being who they are. With “A universally known truth,” Julia Rios challenges us to enter realities where identities, affections and memory are transformed and dissolved as if they were mirages. Felecia Caton Garcia reimagines the colonial tradition of the “Matachín” dancer as a scientific and technological tale with results that are vertiginously human. “Kan/Trahc,” by Iliana Vargas, takes us into a claustrophobic world of artificially recomposed bodies that reveal the dissatisfaction, the loneliness and the fragility of life. In the “Binders,” Angela Lujan invites us to identify with her quixotic superheroes and to read their struggles as the confrontation of the analog vs. the digital, the physical vs. the virtual. “Ring a Ring o’ Roses,” by Raquel Castro, is a story of social isolation and childhood anxieties that combines the popular genre of the living dead with cutting dark humor. Pepe Rojo shares Castro’s interest in zombies, but his piece, “Shoot,” is the frantic and over-saturated experience of a man who eats, dreams, thinks and feels everything through a video game. The contribution of Alberto Chimal, “It All Makes Sense Here,” contradicts and, at the same time, affirms its title by showing us that when suffering is mediated by a screen we really do not care for other people’s tragedies as long as technology keeps us safe. Abuse, trauma, family secrets, sexism and racism battle with seduction, friendship, and joy in “The Music and the Petals,” by Gabriela Demian Miravete. “Clean Air Will Smell Like Silver Apricots,” by Andrea Chapela, seeks to restore hope in a return to nature and life after one of the most significant losses. Finally, Richard Zela illustrates in comic format “Rhizome,” by Castro Rojano, the editor, in which they tell us how ephemeral obects, fantastic secrets and absurd stories only make sense when they are shared and we seek intimate contact with each other. In this anthology, translations and exchanges are not only linguistic, we also see mixes and borrowings of media and genre. Traditionally, movies, television, comics and video games have adapted literary narratives to make them accessible to mass audiences. Conversely, many writers resort to the “language of the cinema,” emphasizing images and actions so that the reader can “see” what the page offers. In Una realidad/A Wider Reality, these loans, thefts or emulations are taken to the extreme; images and digital sounds burst into the immobile black and white of the page to infuse it with cadence, color, movement and urgency. Internet searches, mobile phone messages, security camera videos, and digitally produced images become the medium, the language and the message with which humans, androids, monsters, machines that have yet to be invented, and fantastic beings communicate with each other and with the reader. In a similar way, the bilingual nature of this anthology lends itself to reflect on experimentation and interpretation of reading and writing in two languages. Besides reaching out to a wide audience that may include monolingual readers, this double volume offers a unique opportunity for bilingual readers interested in translation, untranslatability, and the ways in which language limits or liberates our thinking. Some words are translated with “dubious” cognates while several idiomatic expressions offer a different point of view in each language. “Entertain me,” as in “let’s say you believe and want to hear what I have to say,” seems hard to translate and may sound like a request for amusement in other languages, yet it appears directly translated into its Spanish equivalent.  Featured in Somos en escrito Featured in Somos en escrito Interestingly, though it started in the United States with the spelling Latinx for Latina/o, the use of an “x” for gendered nouns and adjectives seems only possible in Spanish. Besides these examples, the fact that “Speculative Fiction” from the English title appears as historias [stories] in Spanish signals more than the difficulty of translation of idioms and culturally bounded expressions; it shows a keen interest in representing the linguistic flexibility and fluid imagination of those who live, imagine and write about the US-Mexico border. As a collection, Una realidad/A Wider Reality gives us access to a multiplicity of voices, perspectives, and ways of writing on both sides of the border that, at times, can be surprising and even unsettling. Here, the form is put at the service of the content; brevity does not impede depth, humor does not hide fear and neither does terror paralyze the movement of life. The authors in this anthology showcase a diverse set of themes, strategies, interests and anxieties that represent Mexican, Mexican American, Mexicanx, Latinx and Chicanx narrative. Even today, in some circles, the literatures of these marginal areas are expected to express racial concerns, local mythologies, authenticity, and border exoticism; however, the imaginative heterogeneity of these stories is so wide that it exceeds thematic and stylistic limits. Readers and critics who believe that Mexican authors only address “Mexicaness” —whatever that means— and that those of Latino diasporas are only interested in the migratory experience will find that, where the State and its institutions divide the world in two, Una realidad/A Wider Reality takes fragments from here and there, narrative splinters, and lost instants to integrate them into a current that, much like the Rio Grande, brings together waters from various sources and branches off into multiple channels. The critical potential of a work like Una realidad/A Wider Reality resides in that it invites us to question our own expectations about what the literatures written and read around the border of Mexico with the United States are or should be. This publication also calls us to recognize that these voices are part of the traditions of both countries and to witness how they claim their right to double cultural citizenship. The challenge is not superfluous and surpasses the novelty of fashionable trends. Genres such as horror, science fiction and fantasy have been disqualified as less literary but have also served to express the experiences and existential conditions of those who live on the margins of society, culture and history. This marginality coincides and is complicated when it is located and enunciated from the border’s interstices. Gloria Anzaldúa taught us that the border is a bleeding wound, an intermediate space (3), a non-place from which literature can erupt.  Featured in Somos en escrito--one of the Five by Ernest Hogan Featured in Somos en escrito--one of the Five by Ernest Hogan On his part, Ignacio Sánchez Prado has shown that Latin American literatures are still uncomfortable for European and Anglo-American centers of cultural capital which do not know what to do with them (8). In this sense, the marginality of these stories is twofold; in addition to resorting to genres of the literary peripheries, they belong to a tradition that oscillates between the West and its liminal areas, especially if we read Latinx as also Latin American.  Anthologist Libia Brenda Anthologist Libia Brenda These short stories —these speculative fictions— can make us confront the realities that are continuously fragmented by borders and that those borders disappear and reappear thicker, taller and, at the same time, more brittle. A Wider Reality: Speculative Fiction from the Bicultural Margins ebook is free and available at this link. Works Cited: Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La frontera. San Francisco: Aun Lute Books, 1987. Sánchez Prado, Ignacio. América Latina en la “literatura mundial.” Pittsburg: Instituto Internacional de Literatura Iberoamericana, 2006. Tobin, Stephen C. “El reconocimiento tan esperado a la ciencia ficción mexicanx en el WorldCon76 del 2018.” Latina American Literature Today 8 (2018). http://www.latinamericanliteraturetoday.org/es/2018/noviembre/el-reconocimiento-tan-esperado-la-ciencia-ficción-mexicanx-en-el-worldcon76-del-2018. Consultado el 7 de Noviembre de 2018.  Reseña: Una realidad más amplia: Historias desde la periferia bicultural/A Wider Reality: Speculative Fiction from the Bicultural Margins. Editado por Libia Brenda Castro Rojano. México: Cúmulo de Tesla, 2018. By Cristóbal Garza Varios autores y traductores de los Estados Unidos y México reúnen sus plumas —o mejor dicho, sus teclados— en una colección de relatos cortos editada por la también escritora Libia Brenda Castro Rojano. El trabajo en colectivo fue inspirado por la presencia de Mexicanx Initiative, de John Picacio, en la convención literaria Worldcon de 2018 (Tobin). La versión electrónica se distribuye gratuitamente en línea y la impresa pronto agotó su primer tiraje. Cada texto aparece en su idioma original y traducido del español al inglés o viceversa. Este doble formato enmarca textos que imaginan mundos posapocalípticos, realidades simultáneas y universos alternativos que se localizan en zonas liminales de muros, portales, entradas y salidas y todo aquello que pueda ser precedido por el prefijo “bi”: bicultural, bisexual, bilingüe, binacional, bilateral, bifocal, etc. La colección nos muestra cómo las dualidades se colapsan en torno a binarismos entre el adentro y el afuera, lo humano y lo monstruoso, lo lírico y lo gráfico, el humor y el terror, el futuro y el pasado, el tú y el yo, la fantasía y los realismos. Las fronteras aquí identificadas, desafiadas, atravesadas y vueltas a imponer son viejas, pero las formas de articulación y disgregación son de nuestro tiempo. Zombis, magos, científicos, gitanos, cholos, traductores, chupacabras, soldados, superhéroes, viajeros del tiempo, bailarinas y baristas pueblan estas realidades bifurcadas por la violencia y vueltas a unir por la imaginación. El prólogo de Castro Rojano explica que el impulso de este volumen es el de establecer diálogos y amistades entre las comunidades de escritores y lectores de ambos países. “Vallas”, de José Luis Zárate gira en torno al último acto de un mago que, luego de haber vivido en los márgenes de la sociedad y de la realidad, debe traspasar un muro real y simbólico para “volver a ser” quién en realidad no es.  Featured in Somos en escrito Featured in Somos en escrito David Bowles nos relata, en “Aztlán liberado”, la furiosa lucha de una pandilla de seres marginales por salvar de la depredación alienígena a los dos países que los han rechazado por ser quienes son. Con “Una verdad universalmente conocida”, Julia Rios nos reta a entrar en universos en los que las identidades, los afectos y la memoria se transforman y disuelven. Felecia Caton Garcia reimagina la tradición colonial del “Matachín” como relato científico y tecnológico con resultados que son vertiginosamente humanos. “Kan/Trahc”, de Iliana Vargas, nos adentra en un mundo claustrofóbico de recomposición artificial del cuerpo humano que desnuda la insatisfacción, la soledad y la fragilidad de la vida. En la “Carpeta”, Angela Lujan nos invita a identificarnos con sus quijotescos superhéroes y con sus luchas, mismas que pueden ser interpretadas como alegorías del enfrentamiento entre lo análogo y lo digital, lo físico y lo virtual. “Rosa de la infancia”, de Raquel Castro, aborda el aislamiento social dándole una vuelta de humor negro a uno de los géneros más en boga: el de los muertos vivientes. Pepe Rojo comparte el interés por los zombis, pero su “Dispara” es la veloz y sobre saturada experiencia del que come, sueña, piensa y siente todo mediante un videojuego. La contribución de Alberto Chimal, “Aquí sí se entiende todo”, contradice —y no— su título por que nos muestra que, aunque no entendamos los sufrimientos y tragedias que aparecen en pantallas, a nadie le importan en tanto la tecnología nos mantenga a resguardo. El abuso, el trauma, los secretos familiares, el sexismo y el racismo se debaten con la seducción, la amistad y la alegría en “La música y los pétalos”, de Gabriela Demian Miravete. “El aire limpio olerá a albaricoque plateado”, de Andrea Chapela, busca devolvernos la esperanza en una vuelta a la naturaleza y a la vida después de una de las pérdidas más significativas. Finalmente, Richard Zela ilustra con sus comics el cuento “Rizoma”, de Castro Rojano —la editora—, en el cual nos cuentan cómo las cosas efímeras, los secretos fantásticos y las historias disparatadas sólo adquieren sentido cuando se comparten y se busca el contacto íntimo con el otro.  Featured in Somos en escrito Featured in Somos en escrito En estas exploraciones narrativas, los prestamos y traducciones no sólo se dan en términos lingüísticos sino de medio y de género. Tradicionalmente, el cine, la televisión, los comics y los videojuegos han adaptado narrativas literarias para hacerlas accesibles a públicos masivos. Al mismo tiempo, muchos escritores recurren “al lenguaje del cine”, en el sentido de que enfatizan imágenes y acciones de modo que el lector pueda “ver” lo que la página ofrece. En Una Realidad/A Larger Reality, estos préstamos, robos o emulaciones son llevados al extremo; las imágenes y los sonidos digitales irrumpen en el blanco y negro inmóvil de la página para darle cadencia, color, movimiento y urgencia. Búsquedas en internet, mensajes de teléfono móvil, videos de cámaras de seguridad e imágenes digitales se vuelven el medio, el lenguaje y el mensaje en que se comunican humanos, androides, máquinas que aun no se inventan y seres fantásticos. De manera similar, el carácter bilingüe del texto se presta a reflexiones sobre la experimentación y la interpretación de la escritura y la lectura. Además de ampliar el alcance hacia públicos monolingües, el doble volumen le ofrece una lectura comparativa a los lectores bilingües interesados en la traducción, la intraducibilidad y las formas en las que el idioma restringe o libera el pensamiento. Escribir “traslación” por “traducción” podría parecer un error: el primer término es astronómico; el segundo, lingüístico. También podría parecer un cultismo anacrónico, pues ambos son “pasar de un lugar a otro”, de un idioma a otro. Decir “entretenme” para traducir “entertain me”, expresión idiomática que quiere decir algo así como “haz como que me crees”; usar “definitivamente” como respuesta afirmativa, o incluso usar en el título “Speculative Fiction” como equivalente de “historias” muestran tensiones enraizadas en diferencias lingüísticas y culturales profundas que nos pueden llevan a la reflexión y a una lectura lúdica. Otro ejemplo digno de atención es la alteración ortográfica de adjetivos y sustantivos que en el español normativo solo aceptan el masculino como inclusivo y que en inglés son neutrales; dressed, ready, child son traducidos como vestidx, listx, ninx. Más que enfocarse en la arbitrariedad de los significantes o en la imposibilidad de la traducción, estos “traslados” de un lugar cultural e idiomático a otro reflejan la labilidad de nuestras lenguas, la flexibilidad de la imaginación y la fluidez de la literatura como medio para expresar la experiencia en las periferias.  El hecho de que se trate de una colección de cuentos facilita el acercamiento a una multiplicidad de voces, perspectivas y maneras de escribir a ambos lados de la frontera que pueden resultar desconcertantes. La forma está puesta al servicio del contenido; la brevedad no impide la profundidad, el humor no nos quita el miedo, pero tampoco el terror paraliza las posibilidades de la vida. Las autoras y autores de esta antología diversifican sus estrategias narrativas para mostrarnos el variado panorama de intereses y ansiedades que existe en las letras mexicanas, Mexican American, Mexicanx, Latinx y Chicanx. Aún hoy, en algunos círculos, se espera que las literaturas de estas zonas marginales expresen preocupaciones raciales, mitologías locales y la autenticidad del exotismo fronterizo; sin embargo, la heterogeneidad imaginativa de estos cuentos es tan amplia que rebasa límites temáticos y estilísticos. Los lectores y críticos que crean que los autores mexicanos sólo abordan “lo mexicano” —lo que eso signifique— y que los de las diásporas se interesan únicamente en la experiencia migratoria encontrarán que, donde el Estado y sus instituciones dividen al mundo en dos, Una Realidad/A Larger Reality toma fragmentos de aquí y de ahí, esquirlas narrativas e instantes perdidos para integrarlos en un cause que, como el Río Bravo, hace confluir aguas de varias fuentes y desemboca en múltiples canales. El potencial crítico de un trabajo como Una Realidad/A Larger Reality reside en que nos invita a cuestionar nuestras propias expectativas sobre qué y cómo son las literaturas que se escriben y leen alrededor de la frontera de México con los Estados Unidos. Esta publicación nos llama también a reconocer que estas voces son parte de las tradiciones de ambos países y a atestiguar cómo reclaman su derecho a la doble ciudadanía cultural. El desafío no es superfluo y sobrepasa la novedad de las modas pasajeras. Géneros como el horror, la ciencia ficción y lo fantástico han sido descalificados como menos literarios pero también han servido para expresar las experiencias y las condiciones existenciales de aquellos que viven en los márgenes de la sociedad, la cultura y la historia. Esta marginalidad coincide y se complica cuando se localiza y se pronuncia desde los intersticios fronterizos. Gloria Anzaldúa nos enseñó que la frontera es una herida sangrante, un espacio intermedio (3), un no lugar desde el cual puede irrumpir una literatura que, como opina Ignacio Sánchez Prado sobre la latinoamericana, resulta incómoda para los centros del capital cultural europeos y estadounidenses que no saben qué hacer con ella (8). En este sentido, la marginalidad en estos cuentos es doble, pues además de recurrir a géneros de las periferias literarias, pertenecen a esa literatura que oscila entre occidente y sus orillas, sobre todo si hacemos extensivo el adjetivo latinoamericano e incluimos lo Latinx. Uno de los resultados de una lectura como ésta es la conciencia de que enfrentamos una realidad fragmentada por fronteras que desaparecen y vuelven a aparecer más duras y, al mismo tiempo, más quebradizas. Una realidad más amplia: Historias desde la periferia bicultural ebook es gratis aquí. Obras citadas Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La frontera. San Francisco: Aun Lute Books, 1987. Sánchez Prado, Ignacio. América Latina en la “literatura mundial”. Pittsburg: Instituto Internacional de Literatura Iberoamericana, 2006. Tobin, Stephen C. “El reconocimiento tan esperado a la ciencia ficción mexicanx en el WorldCon76 del 2018”. Latina American Literature Today 8 (2018). http://www.latinamericanliteraturetoday.org/es/2018/noviembre/el-reconocimiento-tan-esperado-la-ciencia-ficción-mexicanx-en-el-worldcon76-del-2018. Consultado el 7 de Noviembre de 2018.  Cristóbal Garza González, who grew up Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, is a doctoral candidate in the Spanish and Portuguese Department at Indiana University, and an avid reader of science fiction and fiction about scientific history. His work has appeared in Revista Hiedra and in the IU Press sponsored Chiricú Magazine. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed