“Silencio”by Patricia R. Bazán Editors’ Note: The original Spanish version of “Silencio” appeared in the anthology Nébulas peruanas, published by Grupo Editorial Caja Negra in Lima, Peru, in October of this year. Despite the fact that her days were all the same, the sleeping pills helped her stay in the clouds, avoiding the shock of an undesirable reality. Alfonso had no choice but to take their daughters to the United States, where he would process their paperwork required to apply for permanent resident status. Nevertheless, she sometimes wondered if leaving her behind in Lima was a punishment for failing to obtain a tourist visa. She was still relishing her farewell at the airport with masochistic bitterness. For the love of her offspring, Gracia knew her tiny body had to find enough life to endure a great sacrifice. Her husband was clear: she had to cross the border if she ever wanted to lay eyes on them again. The pills gave her a truce because they lengthened her life of an automaton. “Work like a bear, do something to kill time,” she repeated to herself. She didn’t even know how she was getting home: “See you tomorrow, mates”; the Metropolitan bus; walk three blocks and enter without being seen; go straight to your room; throw yourself on the bed surrounded by stuffed animals; fall into the void; a pill to fall asleep, then another, one more, a last one before finally passing out. The unexpected call broke her reverie; she felt compelled to answer, and a hopeful smile emerged from her lips: “Don’t worry, Gracie. I already spoke with Cristian and we have arranged that I will pick you up in Colorado.” Gracia. Full of grace. The grace of God. She carefully observed the room of her future pollero, the man who would guide her throughout the journey: The Peruvian flag of monumental proportions clumsily hung on the wall, a squalid coffee table artfully decorated and holding three pre-Inca huacos with gloomy faces; a colonial-style mirror with wooden borders on the opposite wall. The old furniture fought against the plastic laminate to free itself, a decoration that pointed to a life in transit, ready to flee at any moment. Just as she was beginning to nod-off, Cristian entered, greeted her, and went straight to the point: The journey would be arduous, long, and dangerous, but with a good chance of success. The future leader of the expedition was part of a silent and efficient network of experts in the border geography between Mexico and the United States. First, she would travel alone to Nicaragua, where she would meet her contact, who in turn would pick up future walkers from Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador. The rest of the trip would be made by foot, boat, or in multiple vehicles through Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico, until they reached their final destination: Phoenix. Cristian stressed that, with the help of Providence, everything would be done in a sacred and inviolable silence. A sigh overtook her. She had kept silent all her life, and she didn’t mind continuing to do so, as long as she could see her daughters. Her mother was forced to remarry after her father abandoned them, an experience reflected in the dullness of her graceful eyes. Yet, she never said anything. She had mastered the art of remaining quiet with her head down, and perhaps at long last her silence would serve a purpose. Her suitcase was almost empty to pretend like she was used to traveling. As planned, a Nicaraguan man, one of her many connections on the trip, was waiting outside, as was Cristian, the leader of her expedition. After a courteous greeting, they asked her to step aside in order to spot two other travelers. Gracia thought it would be the beginning of a ruthless journey, a journey her battered body would have to endure. Onward. She considered that, apart from the vicissitudes life had thrown at her, she had had a happy childhood. On one occasion, she was sent to summer school to retake a math class, an excuse that justified a trip to the beach. She told her mother that classes were cancelled, but a classmate gave her away. She actually remembered very few details, as this episode had become somewhat nebulous over time. All it had left was the burning sensation associated with the slap’s imprints. A severe man, her stepfather administered harsh punishments, no matter how light the offense: strappings, slaps, kicking, and being made to eat with the dog on the floor. Her mother watched in cautious terror, as any attempt to protect her daughter would bring dire consequences for her and her youngest. Such long nights were also reserved for the wife, who would face the same repertoire of atonements for having failed to properly raise her daughters, with the added variation that he would make love to her on her reddened maternal body. After a long wait, all twelve left the airport and boarded a minibus, traveling inland until they reached Chinandega, a city whose colonial value they did not have the opportunity to appreciate. That is because they arrived at the most impoverished part; dilapidated wooden houses, unpaved streets, and an intense dust that would welcome all foreigners. They spent the night in a one-room den, something that would become a constant. The next day two more arrived, then three, until the group was complete. There were eighteen: eight Peruvians, five Colombians, two Bolivians, and three Ecuadorians. Sixteen men, one of them lame, and two women. The eldest was sixty years old, and the youngest eighteen. The only other woman in the group was twenty-three years of age, married and childless. She was traveling with her father and her brother; she had left her husband back home in Peru and was excited about the idea of a reunion in El Norte. The Dirty Eighteen. They remained there for a month. In the morning they would wash their clothes and the women cooked for the group, and when there was fried fish, it tasted like heaven. In the afternoon they would either go to the market or to the beach, play soccer, and eat only once a day to stretch the little money they had on them, as if to keep themselves slim. At night they rested on the ground on rickety mats, covered in stained sheets that had seen better days, being careful not to be stung by snakes or scorpions. By now, everyone had mastered the art of communication without uttering a single word. The septic tank was a lair of huge flying cockroaches that would land at night on the visitors’ bodies, only to be plucked during the day from their heads, the palms of their hands, and from in-between their legs. The worst affected were always the unfortunate who slept with gaping mouths. During the time that she remained in this little town abandoned by God and immigration, Gracia could not sleep, not just because she missed her pills, but because the constant effort to protect herself from the formidable brigade of winged insects was eating at her state of mind. The kindness and smiles of the townspeople, however, inspired an inexplicable tranquility. To pass the time away, they would sometimes gather and play cards, making bets on the soap. That was how Gracia came to learn about the lives of the other travelers, fictional lives they had invented to protect themselves from the unknown. Eighteen fabrications, all interwoven by silence and despair. One boasted of having been a sailor who had traveled to Japan where, according to him, he had left several girlfriends; another made up the story of having killed his wife’s lover for being unfaithful, leaving him no choice but to escape from Ecuador; Gracia recounted that her husband had taken away her two daughters for contracting AIDS in one of her many illicit love affairs, a lie that would prevent her from being raped; a certain Ángel told he had a talent for soccer and swore that one day he would be part of the El Norte national team; one named Sebastián, stocky, with straight hair, dark-skinned and who wore glasses, nicknamed El Feo, and with good reason, said that he would meet his girlfriend in Seattle and get married as soon as he arrived in order to conceive children who wouldn’t be as ugly as he. Each story was part of a transparent and sinister tapestry of eighteen intertwined pieces with a sole objective: in El Norte they would be reborn from the ashes of a merciless desert, and its ruthlessly effective police. Cristian distributed the group in such a way that Sebastián would always stay close to Gracia and protect her. She had deteriorated to the point of looking scrawny, ailing, and unthreatening in appearance as a shield against the harsh and inhospitable reality that awaited her. El Feo became her guardian angel; all the others slept in the same fetal position, night after night, like mummies, with the strange premonition of having embarked on an endless journey. At the end of the month, Cristian announced that they would soon leave for the port of La Unión in El Salvador, but not before demanding that they accept their invisibility from then on. They got up early, carefully folded their mats and donned their life jackets before boarding the speedboat where they traveled at a very velocity for two hours, dodging immigration boats. Suddenly, one of the Bolivians unintentionally undid the rope to which he was tied and flew away while the others witnessed his involuntary release, stunned by his unexpected wet death. Gracia would never forget Cristian’s face when the unhappy traveler disappeared; in a matter of seconds, he had lost five-thousand dollars. Once at their destination, the travelers jumped off the boat and dragged themselves to the shore with their backpacks. They did not know if the moisture on their faces was due to the sorrow of having lost a traveling partner or the freshness of the sea water. They arrived at eleven in the morning and began an endless walk. Invisible. Illegal. Silent. Now they were seventeen, doomed. They walked to the border of the mountains where they moved in a single row, becoming one with the soil when the helicopters descended in search of inopportune travelers. It was difficult to distinguish if the fear came from the threatening noise of the propellers or from the supernatural mosquitoes that slipped through their clothes stealthily, without offering them the opportunity to defend themselves, daring them to remain immobile. It was six in the evening when they arrived at a cottage in an abandoned town where they would stay for forty-eight hours. Wet and sandy, the rancher smeared them with horse dung as protection against the flying monsters, holding their breath to avoid contact with the fetid smell. Life was not offering them a truce, but they were closer to El Norte. Gracia had cuts and bites on her legs and feet, and her private parts were scalded from the endless journey in wet clothes. She only had ten dollars, but she was wearing a silver bracelet and earrings, a gift Alfonso had given her for their marriage. The owner asked for them in exchange for clean water and ointments for the wounds on her feet as the nearest pharmacy and well were ten hours away. She spent the night as best she could with four others in the same bed with their feet dangling. A few hours later, two vehicles arrived and they were placed, one on top of the other like a sack of potatoes, covered with a tarpaulin, so they would not arouse suspicion: “If the women want, they can get in the front to be more comfortable…” They formed a human wall, and the men in the group refused to hand Gracia and their traveling companions over to the predatory hyenas. They would rather endure the body heat and the dust than be separated from the group; the collective silence had taught them to distinguish individual breaths, one more method of protection, they thought. When they arrived at a mechanic’s workshop, they were put in two rooms filled with newspapers that served as beds. Those who had money sent for food and shared it with the others, and that’s how they spent three days in a village where even the souls had vanished. At dawn, a laconic one-armed man came and gave a simple command: “Follow me.” He was the driver who would transport them to the border with Mexico. They got into the truck and huddled together as usual. He dropped them off at the border and they walked all night. They crossed mountains, agricultural fields, and farms; they kneaded the cow dung and felt a merciless cold inside their veins. They were invisible, even to animals. They slept outdoors, one next to the other, with their backpacks, and the only change of clothes they had. One for all, all for one. Around ten in the morning, a truck pulled up, and they proceeded to get in, one by one, where they would sit, regimented, and squashed together to make room for the next partner. They rested despite the numbness caused by the other bodies’ proximity. They did not know when they crossed the great city of Guatemala, but when they saw the small room of their seedy hotel, they knew that they had reached their next destination. They ended up three in a bed, had three meals a day and bathed in hot water. Such luxuries came at a high price: Cristian asked them to burn their passports. Now there was no longer any doubt about their invisibility. To protect the two women, the leader of the expedition took the fifteen men to different brothels and in groups of three. He woke them all up at the crack of dawn because they had to be prepared in case they were arrested. They would imitate the intonation, become familiar with a few customs, and learn a national anthem that mattered very little to them, just to pass as Guatemalan. They made the journey to Mexico in a public bus, but not before hearing a recommendation from the guide: if they were captured, they would return to their country, but they would do so alone, without implicating their partners. They stopped in front of a security booth, then Gracia had a panic attack, leaving her with no other recourse than to hold on to the Mexican man next to her. Without saying a single word, the stranger understood, nodded, and took her hand. She was relieved. The seventeen passed immigration control without a problem, and when they got off, they shared a mutual smile: they were in Mexico. They would meet their driver in Chiapas once they took a good bath and had something to eat. Before leaving, Cristian gave Gracia three-thousand dollars in a paper bag to bribe the immigration agents in case they were detained, and addressed the group: “From now on you will meet several polleros. No matter what, don’t accept any packages, and much less cell phones, because they may contain drugs or a trap to reveal your location. Even though we will cross several Mexican highways during off-peak hours, silence will save your life and will continue to be your best friend. As soon as I give the signal, you throw your backpack first through the barbed fence and quickly run across the road. If you don’t want to be caught, you have to be quick.” They set off on the journey, and after a couple of hours, one by one began to jump out of the Ford, bouncing like beach-balls and at the risk of breaking their bones. Weak as she was, Gracia didn’t land safely, and fell into a dung-filled puddle, becoming covered with mud. Since she didn’t have another set of clothes, she moved on, having to deal with her fellow travelers’ faces of revulsion. Once on the other side of the road, they waited for the car that would pick them up after a signal. Her life was at stake, and speed was of the essence. Gracia and five others ended up in a VW Beetle; rotten in filth as she was, she sat on a fellow traveler’s lap. The trip to the outskirts of the Federal District seemed like an eternity, until they finally spotted a large house on the horizon. The pollero offered her clean clothes and allowed the women to bathe first. Their faces were calm; not so much because they were closer to El Norte, but because they couldn’t stand Gracia’s stench. To the surprise of the other seventeen, that night more than fifty other travelers joined the group. Gracia observed the new arrivals with sadness: pregnant women, some with babies in their arms, elderly, nearly blind men, orphaned children, and adolescents. For the first time in her life, the man with a limp didn’t feel out of place. Everyone was crying, everyone except Gracia. At a tender age she had learned that tears were not to be wasted and should be reserved for special occasions. They scattered the next morning. Upon arriving in Mexico City, the pollero informed them that they would take the subway to Guadalajara. They ended up in the home of a woman in a wheelchair ho rented rooms on the third floor to smugglers in transit. They couldn’t go out; they cooked at the house and shared two rooms; one for the women, and one for the men. The house was large, and the widow lived with her daughter, a pretty fifteen-year-old girl quite precocious for her age, who immediately fell in love with one of the boy travelers. Desperate to escape her fate, she reserved herself for someone who wanted to take her, and she flirted with anyone who would pay attention. Noticing the concupiscent eyes of her young traveling partner, Gracia asked him to feel sorry for the conditions in which the owner of the house lived; after all, she was helping them. “If it weren’t for her, we wouldn’t be able to cross; no matter how much the girl insinuates herself, respect her,” she advocated. In the end, the boy chose to cross the border rather than to become involved with the girl. The terror of being reported was a key factor: if the owner found out that her daughter had been touched, they would all end up in jail and one step away from deportation. When they went to sleep, Gracia discovered that the boys had jokingly entered her room. Wasting no time, she grabbed one of her trucker boots: they couldn’t yell or ask for help because they would end up at the police station: “Hey asshole, what’s wrong with you?!!! I don’t like you being in my bed. Moron! Don’t you know that I have AIDS and that I can infect you?” she said while hitting him on the head. “Don’t hit me like that, my head hurts!” said the scoundrel, as he fled to the adjacent room, where his minions were waiting for him. They left them alone and apologized as soon as they got up: “That was a close shave,” Gracia murmured in relief. At dawn they began a longer stretch than the usual and crossed Guadalajara until they stopped at Villa Hermosa, a shantytown on the outskirts of the city. A seedy camp awaited them, with only one toilet, no water, where everyone defecated and left their shining fresh lumps of excrement, scenting the outdoor shower. Six boys slept on a couple of bunks, while Sebastián laid on the ground next to Gracia. They slept like this until it was time to cross. Of Cristian’s group, El Feo was the first to disappear and Gracia the first to notice his absence; she felt helpless without him. The next day six more left. The destination was Piedra Lisa in New Mexico; there, Cristian would contact some relatives to release a few, slowly but surely, once the debt was paid off. Gracia went out with eight men and the other woman in the group to take a bus. Suddenly they were stopped by an immigration officer. Cristian had warned them that all of Mexico was swarming with police officers due to pressure from the United States. They pretended to be asleep, and with deep sadness, they witnessed their own arrest. “Fifteen-thousand dollars lost,” Gracia muttered. Moving on. The wandering seventeen. Once at the police station, she began to cry out of powerlessness and then remembered the three-thousand dollars Cristian had given her to bribe the immigration officers. The fear that the agents inspired in her was so great that she saw them as towering, ferocious, and ignominious. She gathered herself and thought clearly. They separated her from her companions and a female officer took her to a cold and dark room where she had to undress; The officer’s jaw dropped: Gracia’s belly was protruding, and she looked pregnant. Years later she would remember how her abdomen, the product of so many Peruvian potatoes and rice, would save her life. “Do you bring something in your private parts? Are you clear? You don’t have anything? Where are you going?” the agent asked. “I’m on vacation with my husband. I don’t bring much, I’ve been told that Mexico is a dangerous place so I’m travelling lightly, but I have my money. Once we visit our relatives, we return to Guatemala,” Gracia replied, imitating the Guatemalan intonation. “You better. This is no place for illegals here. There are too many and we don’t want you either!” concluded the officer. They released them and sent them back penniless to Villa Hermosa where they found out that some of their traveling companions had been deported. At least something good came out of Cristian’s three thousand dollars. It was at this precise moment that she understood that her silence was a gift rather than a curse. When they left, Cristian took them to a clean and safe house where they stayed until January first. They sent for a roasted turkey, and for the first time, they drank tequila, delicacies that anticipated the most dangerous part of the trip: crossing the desert on the outskirts of Phoenix, a savannah that required black clothing for camouflaging in order to become one with the desert. They left their last lodging in Mexico at night for a bus stop that would leave them at a precise point to cross the border into Arizona. The trip lasted six hours in total silence, dressed in black, in the darkness. The mist was thick, and on the horizon, there was a piercing light that guided them on the abandoned road they were traveling. Suddenly, the vehicle stopped and, one by one, they began to fly off in whichever direction they could. When it was her turn, Gracia, confused, didn’t know where to run. She froze and after a few seconds she realized that truck had moved on; she was in the middle of nowhere, alone with her terror. She was left facing the gray density and unable to scream because her silence had eaten her words before leaving. At that moment, an energy transformed into matter invaded her, seized her hand vigorously, and forced her to follow it. She was frightened to death: convinced that she had penetrated the unknown, she resigned herself. In the midst of this nebulous episode, she remembered Alfonso’s premonitory words: “Gracie, honey; I don’t want to scare you, but if there comes a time when they are going to rape you, leave it alone, cooperate, the more you resist, the more damage they will do to you.” She let herself be swept away by the guiding hand, felt a wooden bridge under her feet, scrambled over huge boulders, thinking she was going to an inescapable end. She continued. Once the mist cleared, Gracia realized that she was safe: the hand released hers and left. She noticed a field with many stones, typical desert stones. Her loneliness was immeasurable. Little by little she began to distinguish a myriad of men, women, adolescents, children, and elderly people sprouting from the stones. Human rocks. She leaned back on something hard and immediately felt a warmth: the rock took off its mask, revealing a familiar smile. Both the man with a limp and Gracia greeted the dawn with pouring rain, and it was then that they understood the reason for the term mojado, a word invented by the rain itself as a symbol of solidarity with those who cross the desert. She felt calmer and settled in with the group, hugging the black garbage bag that Cristian had given to each of them before leaving. The sixteen pilgrims became forty-six; they were Indians, Brazilians, Europeans, Africans, and Chinese: they had crossed the border. Gracia felt an unknown tear invading her face, only this time it was not caused by a humiliating slap on the face, but by the joy of being alive. Upon resuming the trip, Gracia faced the immensity of the desert, knowing that she would remain stagnant since her aching body would not cooperate. She was stumping through mud, stumbling, physically and emotionally exhausted. She gave up twice because the cramps had taken hold of her legs until she heard the pronouncement of the main pollero: “If this woman can’t keep up with us, we have to leave her behind.” Her partners refused: “She is going to continue walking.” The water ran out due to the number of travelers; they resisted until the last moment to carefully drink it and savor it to the last molecule. At nightfall they threw themselves into the arms of the vast sheet of arid land and Gracia felt sick again. She had chills, a headache, and her wet blankets did not provide her any relief. She still had a long way to go, and six specialized smugglers had arrived to cross the desert as the group had grown. They had to move. In a curt and insensitive way, one of the polleros stated: “We have to continue to the other side of those mountains. We walk during the day and sleep at night in the desert.” Cristian and two other polleros led the group while the remaining four carried huge backpacks containing thick blankets, pallets, telephones, and” supplies, and withdrawing from the group at night. The polleros slept comfortably and the mojados with their garbage bags. The women had the option of sleeping in their camp, but the men begged them to stay. They protected themselves in silence. When the smugglers sensed the flight of a helicopter or a small plane, they immediately shouted: “Pretend to be a ball and don’t move.” In the distance they looked like stones, and the darkness protected them. They were stones day and night. They walked like this for three days, sensing that the desert was their magnanimous mother. Gracia began to vomit and between the pain she became delirious, “I want to continue. Give me a drug or something, give it to me because I want to continue, I have to see my daughters.” Someone gave her a Coca-Cola and her traveling partners donated their ration of bread to force it onto her, thus giving her energy. Her bleeding feet were about to burst from the blisters, but her will was stronger. Through Cristian, Gracia found out that Sebastián had been captured on an interstate in Phoenix and was going back to Mexico; she had no one. She was completely sickly and when he saw her, the lame man was the first to offer to carry her on his back: “No, you are not going to stay here!” and so they moved on; everyone took turns carrying her, and at the end of the day they would put her on a blanket to rest. The straw that broke the camel’s back was the last hill and Gracia gave up; they decided to leave her. Cristian asked that they take him and Gracia to the first ranch they found, “I don’t want this woman’s death on me here,” he said. Six carried her, making sure they were not seen when the house’s sixty-two guard dogs came out to greet them, and they all fled to hide behind a broken truck. Once the mojados left, Cristian cried for help: they gave themselves up. An hour later, a blonde, blue-eyed agent came in a truck; he examined her, she had a fever and was crying, “Please I need to see a doctor.” Cristian declared: “I am her friend, and I could not leave her alone.” In flawless Spanish, the immigration officer asked if she was pregnant. “I need to take a shower,” she replied as she removed the blood-soaked washcloth. He took her information and brought them to the border near Nuevo Laredo so she could see a doctor. They went to a nearby pharmacy where they gave her medicine for pneumonia. “Don’t try to cross the border into the United States, please,” the blonde officer advised them and politely said goodbye. They arrived at a hotel, she bathed, took her medicines, and slept like a log. “I’m not going to last, I can’t walk. I’m going back to Peru, Cristian. Thanks for everything.” “Your husband is willing to pay, I can’t keep losing any more money. Besides, I like you,” the guide answered while he dialed a number. They went to a house where she slept on the floor: there she found Sebastián, now recovering from a heat stroke. Through his contacts, Cristian obtained false documents to enter the United States and taught him a little Mexican Spanish. Two days later, he introduced her to a pollera who had three young daughters and made Gracia their aunt. “So long as they don’t ask you, don’t say anything,” the mother advised. They got into the Mercedes Benz and Gracia caressed the girls as if they were her own. Arriving at the checkpoint, the woman explained in perfect English: “I am going to McDonald’s with my family.” The sounds of the English language sounded like a heavenly hymn to Gracia. They passed and, after eating, the woman left her at a young couple’s home. The next day, she was sent to Colorado, where Alfonso was waiting for her. Gracia never saw Sebastián again, but she found out from Cristian that he, the lame man, the self-confident man who threw himself into her bed, and the Peruvian woman who was traveling with her brother and father had crossed with thirty-six other travelers. They were now gringos and they paid true homage to the phoenix: they had been reborn. It was the last trip that Cristian carried out before retiring and marrying Lauren, his girlfriend of ten years. Later on, Gracia read in the newspapers that two of the polleros ended up in Mexican jails, one for raping and the other for using illegal immigrants as mules. The travelers opted for oblivion and the experience died with them, aware of having been marked for life. Thirty years after that inconceivable test, Gracia still remembered the protagonists of the nébula that had defined her existence forever. From the window of her house in Forest Hills, and before taking a sip of tea, she whispered: “Thank you, Silencio.”  Patricia R. Bazan was born in Lima, Peru. She arrived in the United States at the age of twenty-one and has been residing there for over forty years. She is a professor at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Madison, New Jersey, specializing in Spanish and Latin American literature, as well as multicultural, interdisciplinary, and Latino studies. Despite having a successful academic career, her true vocation lies in writing. For the past few years, Bazan has been writing semi-autobiographical fiction. With this purpose in mind, she published Cinco nébulas de obsesión. Estelas de vida y muerte (2019) and Lazarillo en Londres (2022). In the fall of this year, Nébulas peruanas, Bazan’s second collection of short stories, will be released. The themes of reincarnation, the Spanish conquest, social inequality in Latin America, the presence of the United States in Peru, and tales of the undocumented permeate the entire narrative.

0 Comments

Gringasby Ainhoa Palacios Each stop sign’s location was known to her. There was no need to switch lanes or deal with bad traffic, which is why it was the only road my mother felt safe driving on. One long winding road — Grand Regency Ln. It snaked past an AMC theater and a T.J.Maxx, before crossing a large intersection and keeping on past a Target and Barnes & Noble, finally and gently leaving us at Wal-Mart's doorstep, where we now got our groceries from. Before Wal-Mart, there was Dollar Tree. We'd walk there every Wednesday evening, my mother’s only fleeting time off. We took an hour skimming the two food aisles as if our shopping list wasn’t the same as last week. Elena routinely dumped ten cans of Vienna sausages in the shopping cart, the metal tins making a loud clank that had become so sweet and familiar. A tradition almost. She then immediately disappeared and came with a box of ramen which she stuck on the bottom rack of the cart. Baked beans, tuna, Nissin Cup Noodles, Uncle Ben’s instant rice, a 60-count bag of silver-dollar pancakes, a loaf of white bread, ham, suspiciously-gold-and-individually-wrapped-slices-of-cheese—that was our cart. During the 45-minute walk home, we each carried as many bags as we could stand, stopping often to readjust and shake our hands out. We played I Spy—better known to us as Veo Veo. Those Wednesday-dollar-store-veo-veo grocery trips only lasted a few months, stopping when my mother finally bought a car. The car was red. The seats inside, a tan suede with random stains of unknown origins. One of the back passenger doors was imprinted with a bowling ball-sized dent. It had a working radio and A/C, something I only learned to appreciate months later when a teenage girl rear-ended us, and the following car my mother purchased for $2,000 didn’t have the luxury of a working radio and A/C. The little red car had good gas-milage and airbags too, though those details I learned from my mother's praising of the car. “It is such a blessing, this little car. It serves us well,” she would say in response to Elena who complained that it made a sputtering sound so loud you couldn't hear ambulances behind. “It is embarrassingggg,” Elena whined, drawing out the last word with the sarcastic tone of an almost-teenage-girl. I can’t remember when Wal-Mart became synonymous with ghetto. When all I saw were other brown people in much too small shirts, their bellies draping over jeans. Men with greasy ponytails and lightly stained ‘wife beaters’. I can’t remember the moment I started to say to my friends, "I only shop at Target", where every aisle was brightly lit and organized and the bathrooms didn't smell like shit. Where there wasn’t a McDonalds but a Starbucks, and the employees were white teenage girls instead of chubby worn-out single moms. But before there was "I only shop at Target", there was me, 3’ 8” with unruly curls, holding my mom’s hand and asking question after question about the first day of school. “¿Cómo se llama mi professora? ¿A qué hora viene el bus? ¿Qué voy a almorzar?” It was our very first back-to-school shopping trip for our very first day of school in America. America. Each time I heard the word America I was filled with a sense of wonder. America. The land of opportunity. America. The land of English. America. The land of blue-eyed children. But before I could dive into 'America', we needed uniforms. I asked my mom what they looked like. “No se,” she said. They’d told her to go to a Wal-Mart. “You’ll see them there,” they assured. This confused me. How would we magically know which ones they were? Why didn’t they show her a photo? But it didn’t matter. I was six and a lot of things confused me, and I knew if I asked, I wouldn’t understand any better, and Elena would roll her eyes and tell me to stop being so pesada. The uniforms were there. Right in between the girl’s section and the boy’s section. There were choices. The general idea was a polo shirt, and any linen bottom so long as the colors were bleach-white, hunter green, navy blue, khaki, or maroon. “Algo más que planchar,” my mother said with a grunt. She hated ironing. She hated all things housework. The day we walked into our new American apartment, she couldn't stop talking about the washing machine. How grateful she was she would no longer have to wash clothes by hand, how it would save hours of her life, how this was all she’d ever wanted in life, how she felt like she could breathe again. Elena called her dramatic. Mom told us we could each get two bottoms and five shirts. Seeing Elena’s face of outrage, she followed her statement with “Yes, Elena. You’re going to have to wear the bottoms twice. But now, you can wash them with our new washer and dryerrrrrr!” she drew out her last word as if she was mocking Elena… “Maybe later we will buy more.” My mother never used the word “afford”, but even at six, I knew that’s what she meant. My mother held onto two papers, each a list of the supplies Elena and I would need. “¡Quiero ver! ¡Quiero ver!” I jumped by her side trying to peek. My mother handed me my paper, and Elena’s hers. There was thick bold font at the top. From later syllabuses, I imagine this one must have said something like, Mrs. Ramlow’s 2nd Grade Class. Below the fat black font was a bulleted list of yet more words I could not read. My mother’s handwriting beside each item was useless to me. I could read some cursive, but not hers. Hers was far too harsh and edgy. I must have looked defeated when I handed her back the paper because she smiled, winked, and blew me a kiss. “I’ll read it to you and you go get it, okay?” Oh, how excited I was to run around the aisles, be on my own, free to look for new mechanical pencils and three-ring binders. I knew exactly which to grab, the generic brand, the things that sat above the lowest number. The night before school started, I couldn't sleep. “¡Estoy muy emocionada!” I shouted while I bounced on my mother’s bed. “¿Quieres té?” she took out a mug and pulled out a lilac box with a picture of a snoring-pajama-wearing-bear sat in a rocking chair. She made this tea for herself every night. And every night, she also reached for the clear bottle of Agua de Azar from the medicine cabinet. I never did know what Agua de Azar was, other than what she gave me when I had a stomachache, or felt like throwing up, or couldn’t sleep, or cried so hard my eyes swelled. We pulled up to a brick circular building in our sputtering red car and parked. A thin white woman and a plump brown woman were waiting for us in the lobby. The white woman shook my mom’s hand, while the plump brown woman knelt without actually letting her knees touch the carpet.“¡Hola!" she beamed. "Me llamo Mrs. Lopez. Yo seré la maestra de ESOL para las dos. Es un gusto conocerlas." ESOL, I’d find out later, stood for English for Speakers of Other Languages. Elena and I both nodded with a smile, mine always naively bigger than hers. We walked into the white lady’s office, who I’d already nicknamed La Gringa, though my mother would later remind me to use her name— Principal Kathy. “Okay, bebe. See you later okay?” my mother kissed me goodbye. I held Principal Kathy’s hand though I didn’t particularly want or need to. They felt strange, so boney and pale next to mine. Principal Kathy was both tall and lean. She had stringy blonde hair and a very pointed nose that reminded me of the parrot we once had in Peru. Her face was lined with deep grooves that left me unable to decide if she was pretty or not. All in all, she looked exactly how I’d always pictured a gringa. We walked in silence towards our classrooms. Mine came first. When we got to the door, the white lady inside was also tall, but this time, curvy with hair that reminded me of burnt orange peel. Another gringa. A more eccentric one. As soon as she noticed us, her face erupted into a smile, her eyes looking at me like I was the cutest kitten in the litter. When Principal Kathy left with Elena, I sat in a cubby-holed-desk just like the movies. Burnt-orange-peel-haired-Mrs. Ramlow turned on the television. There was an image of the American flag which for some reason prompted everyone to set their pencils down and stand up, their chairs making a piercing screech as they grated against the tile in unison. They put one hand over their chest. I did the same. The room echoed with voices. I opened and shut my mouth trying to match their pace. Mrs. Ramlow looked at me subtly, a tiny smile peeping as if she were holding back a giggle. As if the kitten was somehow cuter than she expected. We were supposed to write an expository paper. Expository, I learned in ESOL, meant it had to explain something. It had to explain why blue was my favorite color. “Necesitas cinco párrafos. El primer, es una introducción con tres razones por qué te gusta azul. Luego, un párrafo para cada razón. El último párrafo se llama the conclusion. Dices tus razones otra vez. ¿Entiendes?” Mrs. Lopez explained in our classroom trailer. I nodded. I understood. Mrs. Lopez said to work on it for homework. If I had trouble, she would help me. During math the next day, when I was supposed to go to ESOL, Mrs. Lopez didn’t come. She must have been sick. So when Mrs. Ramlow began to collect the writing homework—after math, and before cursive—I handed in what I had. It sounded like a yelp, what she did. It wasn’t quite a shout, but enough that all twenty six-year-olds looked up at her. Her eyes were wide with excitement and aimed straight at me. I froze. She gently waved me over. “Did you write this? All by yourself?” I nodded. “Amazing!” she jumped out of her desk and grabbed the classroom telephone hung on the wall near the whiteboard. When she was finished, she reached for a green piece of paper on her desk the size of a sticky note, wrote my name, and checked a couple of boxes.“Go to Principal Kathy,” she said. I took the paper slowly and backed away the way someone might if they were faced with a rabid dog, afraid Mrs. Ramlow would yelp again. In her office, Principal Kathy gave me candy. She put a stamp on my paper that read ‘Great Job!’ with a blue thumbs-up beside it. She was on the phone, and I was certain it was with my mother because she was opening her mouth wider than normal. I remember her doing the same exaggerated mouth movements the first day we met months ago. She handed me the phone. “¿Bebe?” “Hola mami.” My mother explained, Principal Kathy called to tell her I wrote an amazing paper about the color blue for language arts class. She called to say they were all very proud of me and she should be too. I thought about what happened when I did something good at home. How my mother would say, “¡Chocala!” raising her palm for a high five. With an o-shaped mouth, she mimicked the sound of a stadium full of fans. Then she’d say, “Esa es mi chica.” And that was it. Party over. But now, I was sat in Principal Kathy ’s large Victorian chairs, with the phone pressed to my ear, after the yelping, after the candy, after the stamps, and the only explanation was: the gringas around me were intense. A bit ridiculous. Over the top. Exageradas. As I met more gringas, and more blue-eyed children, my conclusion evolved. America. The land of the underachieving. America. The land of the complacent. That explained why each time I got an A, there was candy, an ice cream party, a pizza party, awards. America's bar was set lower. Nobody had to work as hard to be good. To be recognized. To be special. Maybe that was the privilege I heard everyone talking about. I found that expository paper when I was twenty-five, months after my mother died. It was in a folder she labeled Neve, besides the one labeled Elena. Each one was a collection of everything good we’d ever done. There were crafts, and awards, and drawings, and there was that story. I like the colr blue. I like the colr blue becuse it is colr the ski, the oshen, and ice.  Ainhoa Palacios was born in Lima, Peru, and moved to the US at the age of six. She grew up in Florida with her mother and sister, and grandmother who occasionally visited during summers. She graduated from the University of South Florida with a B.A. in journalism, but soon after remembered it was a different kind of storytelling she loved. Since then, she has completed a novel and countless short stories, one of which was recently long-listed in Fish Publishing’s Short Memoir contest. She is currently working on a collection of short stories of which Gringas is part. Ainhoa lives in Shenzhen, China with her dog Mambo. Somos En Escrito is the first to publish her work. Excerpt from |

| Mienten los mapas -- son colchas de parches sin sentido de colores pasteles (lila, celeste, lima, limón, naranja, rosa) con nombres, costuras arbitrarias con que imaginamos a la Tierra pretendiendo poseerla y le llamamos ‘mundo.’ La Tierra no tiene costuras ni fronteras -- ríos y barrancas, sierras, pantanos, desfiladeros, junglas y desiertos, cascadas y saltos, mares sí, pero nunca fronteras. Los mapas mienten. |

Mi familia llegaron cuando la revolución mexicana de 1910 llegaba a su fin en 1920, mis padres apenas adolescentes. Así es que yo me crié bicultural, bilingüe entre y participando en dos distintas culturas. Mis padres siempre insistieron que conserváramos nuestra cultura mexicana y lengua castellana a la vez que aprendiéramos el inglés. No siempre fue fácil. La cultura estadounidense es poco tolerante de lo extranjero e insiste en que el inmigrante se asimile.

En la escuela nos castigaban si hablábamos en español en la aula o el patio de recreo y aun muchos nos sentimos obligados a defender nuestros propios nombres. El prejuicio en la sociedad en general es grande. Muchos padres para proteger a sus hij@s de los efectos de este prejuicio les permitían hablar sólo inglés para que avanzaran económica y socialmente. El costo de asimilarse es grande.

| A Una Anciana Venga, madre -- su rebozo arrastra telaraña negra y sus enaguas le enredan los tobillos; apoya el peso de sus años en trémulo bastón y sus manos temblorosas empujan sobre el mostrador centavos sudados. ¿Aún todavía ve, viejecita, la jara de su aguja arrastrando colores? Las flores que borda con hilazas de a tres-por-diez no se marchitan tan pronto como las hojas del tiempo. ¿Qué cosas recuerda? Su boca parece constantemente saborear los restos de años rellenos de miel. ¿Dónde están los hijos que parió? ¿Hablan ahora solamente inglés y dicen que son hispanos? Sé que un día no vendrá a pedirme que le que escoja los matices que ya no puede ver. Sé que esperaré en vano su bendición desdentada. Miraré hacia la calle polvorienta refrescada por alas de paloma hasta que un chiquillo mugroso me jale de la manga y me pregunte: — Señor, jau mach is dis? -- |

Y ahora el Presidente de los EE.UU. Pres. Trump (llamado entre nosotros con el no muy afectuoso apodo Pres. Trompudo) racista y fascista, ignorante, arrogante y descorazonado hasta las cachas intenta, con el apoyo de su índole, expulsarlos a sus países natales, países extraños para ell@s, países no suyos — México, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua y tantos más. Se les han llamado “Soñadores” apodo que origina en un plan del presidente anterior Pres. Obama para protegerl@s.

Nuestros soñadores

El país que echa fuera

por falta de documentos

a sus soñadores

se hiere a si mismo.

¿Que otra tierra conocen?

¿Que vacío dejarían

en la consciencia,

en el corazón del pueblo?

Es arrancarle las balanzas

a la justicia, apagarle

el antorcha a la libertad.

Sería como si el águila

con su propio pico

y sus garras se rasgara

su propio corazón

ya envenenado por la crueldad.

De fronteras y muros

los sueños y la necesidad

saben los mismo

que las mariposas, las aves,

el olor de las flores.

Si no protegemos

a nuestros soñadores perdemos

nuestras almas y sueños.

Con la ascendencia del Pres. Trompudo se ha demonizado el emigrante. El presidente les ha llamado violadores, asesinos, ladrones, especialmente a los emigrantes mexicanos, centro-americanos, latino-americanos (y además terroristas a los emigrantes musulmanes.) El fascismo, el racismo, el nacionalismo y el odio son patentes y se han normalizado en la discusión política estadounidense. Pero lo tenemos que decir claro --

Decirlo Claro

Dicen los bobos

que venimos de mendigos

estómagos vacíos, vacías las manos

para quitarles lo que ya

sus propios canallas y bribones

les robaron.

Sí, venimos con hambre

huyendo la violencia

a donde la riqueza

del impero se concentra

pero con las manos llenas

de nuestras artesanías y labores,

corazones llenos de bailes y canciones,

con nuestra cocina rica en sabores.

Le traemos alma a una cultura desalmada;

traemos el arco iris

y prefieren el gris de sus temores.

Se empeñan en construir muros

si lo que se necesita es puentes.

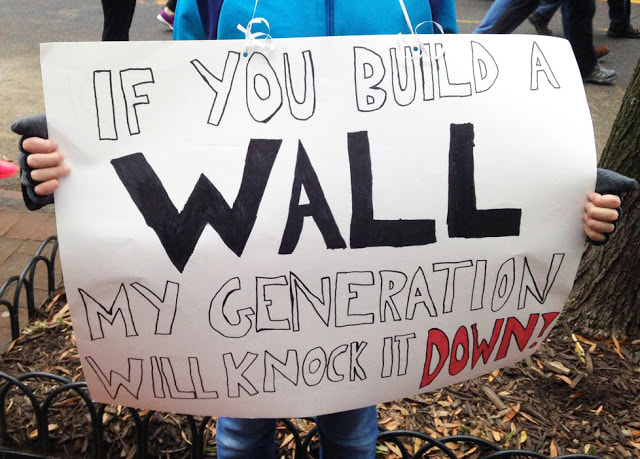

La frontera se ha militarizado y se ha hecho un frente de batalla. Y el Tompudo se empeña un construir una gran muralla por toda la frontera entre los EE.UU. y México a un costo aproximado de construir de 70 billones de dólares y de mantener a 21.6 billones de dólares. Y neciamente insiste que la pagará México. Pero no se le puede poner precio al costo del sufrimiento que ha causado, que causa esta política. Los emigrantes son aprendidos y encarcelados, las madres, los padres separados de sus hijit@s, muchos de ellos infantes, l@s niñ@s metidos en cárceles separadas, desparramados, enviados lejos. Y aunque las cortes han declarado estos hechos ilegales y exigido que se reúnan las familias, muchas todavía no se han reunido y niñ@s se han perdido. La crueldad, el sufrimiento hiere la imaginación.

Es tan amable la luna

La luna llena se cuela

por entre las rejas de la cárcel

de niños

para recoger sus sollozos

en su delantal de luz

y llevárselos a sus padres

en cárcel de adultos

y traerles lamentos y bendiciones

de sus madres, sus padres

a los niños.

Es tan amable la luna

que no niega su luz

ni a los malvados traficantes de angustia.

Es tan amable la luna

Y ¿que graves exigencias motivan a estos padres, madres a arriesgar tanto por emigrar a los EE.UU.? Vienen a donde se concentra la riqueza del imperio huyendo de la pobreza y la violencia de sus países causados por la política estadounidense: tratados de “libre comercio” que han sido desastrosos para la economía de México, la cínica “guerra contra las drogas” que ha traído violencia atroz a México, los Acuerdos de Mérida que han militarizado el gobierno de México y lo ha hecho aun más violento.

Pero no es solamente México sino es así en toda América Central y en partes de Sud América. Se cultivan y se apoyan gobiernos abusivos por el poderoso EE. UU. que para el bien de los ricos mantienen a sus pueblos en pobreza y represión violenta, vendiendo sus tierras y recursos naturales a empresas extranjeras estadounidenses e globales. Y l@s que resisten y defienden la Tierra (gran parte indígenas y mujeres) son torturados y muertos. Un caso representante de muchos, muchos otros por todas las Américas es el de Berta Cáceres de Honduras:

a Berta Cáceres

y a todos los mártires

de las Américas

muertos defendiendo la tierra

| Por medio milenio y más hemos muerto defendiendo la tierra, los bosques, los ríos de invasores extranjeros cegados por la codicia, enloquecidos por la ganancia en moneda sangrienta. Hemos sufrido traidores infectados por esa locura que por esa misma moneda venden a sus propios dioses. Nuestros huesos siembran la tierra, nuestra sangre la riega y el sagrado maíz a veces nos sabe amargo. Pero seguimos luchando y nuestros huesos y sangre crecerán un nuevo mundo en flor. |

El capitalismo desenfrenado lleva al fascismo y esto lo vemos por a través del mundo actual. Las guerras y tiranías casi todas a causa del capitalismo desplazan una gran cantidad de gente huyendo del la pobreza y la violencia para sobrevivir. La migración es unos de los “problemas” más grandes del día no obstante que la humanidad siempre ha migrado desde su origen en África hace tres cientos mil a dos cientos mil años.

Migración

¿Qué sabe la mariposa de fronteras?

¿Qué sabe de banderas?

Cruza todo un continente,

el movimiento su herencia.

Así es con nosotros,

nuestra historia migración

de años, de siglos, de milenios

antes de que historia hubiera

y que formáramos mitos en el cerebro.

Nuestros pasos hechos de sangre,

de lágrimas, de risas, de sudor

marcan nuestra eterna búsqueda

de hogar señalado por el Dios,

o el águila comiéndose una culebra

o quien sabe que señas arbitrarias.

Pero son inseguras nuestras moradas --

hogar es la Tierra redonda y sin costura;

la circundamos y si patria veneramos

es pretensión, es mito, es mentira --

buscamos abrigo, alimento, libertad, la vida.

Abajo con fronteras, abajo con banderas

que si justicia y paz hubiera

no tuviéramos que vagar tanto por la Tierra.

Nací, vivo en y soy ciudadano de los Estados Unidos de América pero más que nada me siento ciudadano del mundo. Mi lealtad es a la humanidad a cual pertenezco y a la Tierra que nos dio nacer y nos sostiene. Mi ciudadanía estadounidense y terrestre me obliga a ver críticamente a mi país, al mundo, a la humanidad. Pero si he pintado a mi país en matices sombríos no es completamente fiel el retrato. Muchos, muchos estadounidenses no son racista, ni tóxicamente nacionalistas, ni injustos, ni crueles, ni capitalistas. Y son muchos los problemas del imperio y me he enfocado sólo en la migración. Es muy grande la resistencia contra las fuerzas del fascismo, es grande la compasión y el deseo por la justicia. Muchas ciudades y aun estados se han declarado ciudades, estados “De asilo” para proteger a los inmigrantes indocumentados negándose a colaborar con la policía federal en la persecución de los inmigrantes. Diariamente hay manifestaciones a las puertas de las cárceles, la frontera, los aeropuertos, los edificios de gobierno, las calles en apoyo de los inmigrantes. Hay una gran lucha entre las fuerzas del fascismo que controlan el gobierno y las fuerzas demócratas. Estamos en crisis y son tiempos temerosos.

En cuanto a mí como viejo y poeta

Te Digo

Te digo que estoy cansado

de no poder darle la espalda

a la injusticia y crueldad del mundo.

Quisiera en vez contarte

lo que el sauco y la secoya,

la piedra en el arroyo hecha lisa

por el toque suave o brusco

del agua me dicen.

Quisiera decirte los cuentos

del lagartijo y la mariposa,

cantarte las canciones calladas

de la madreselva y el romero.

Quisiera escribir versos de amor

a la Tierra, a la vida, a ti.

Pero no puedo darle la espalda

a la injusticia y crueldad

del mundo que causa

tanta pena y sufrir en la Tierra.

Mis versos de furia y protesta

son también poemas de amor,

de un amor traicionado y herido.

© Rafael Jesús González 2018.

“Political poetry is that which addresses, in opposition or support, criticism or justification, the institutions and norms that govern us.”

By Rafael Jesús González

Festival Proyecto Cultural Sur in Montevideo, Uruguay in October 2018)

It never happened. I was asked to open the discussion; I stated my position, and read my two poems, one of Roque Dalton's, and the last poem of Javier Sicilia. My three colleagues completely ignored instructions to the panel, essentially said that the creative act was in itself political and hence so was all poetry, and proceeded to read from a sheaf of poems they had brought with them. The event became simply a poetry reading; there was no round-table discussion, nor did the audience have an opportunity to ask questions.

Somewhat exasperated, I said that if writing poetry is itself a political act and all poems are political, then there is nothing to say and furthermore that we could not call HD's pear tree poem, or Williams' red wheel-barrow poem, or Stevens' blackbird poem, or Basho's frog poem political at all. Though a love poem could be political such as Arnold's Dover Beach (definitely political, but is it a love poem?). And that closed the conversation that we never had.

Of course my colleagues know perfectly well what is a political poem and what is not, and though they maintained that the writing of poems in itself is political and hence all poems implicitly so, they did not read HD, nor Williams, nor Stevens, nor Basho to bolster their contention, but the poems they had chosen to read were unquestionably, undeniably, powerfully political.

In my opening remarks I had said that because we are social creatures everything we do is political; not voting in an election when we can is itself a political act. Furthermore, I said, an act, a poem, is weighted, or not, with political meaning by the context in which it is written. In the context of contemporary environmental degradation, I said, the nature poetry of Mary Oliver may be read as implicitly political.

That said, if HD had written her poem at a time when pears were poisoned by pesticides, or Williams' his when red wheel-barrows were outlawed in New England, or Stevens’ when blackbirds were hunted near extinction, their poems could have a strong political glow. For that matter, had Basho written under a tyrannical regime that criminalized freedom of expression to maintain the status quo, his frog's splash could have been, though implicit, politically loud indeed. It is all context when all is said and done; all that exists is relation. Such is my theory of relativity.

But we still need a working definition of what political poetry is, and for that I offer:

“Political poetry is that which addresses, in opposition or support, criticism or justification, the institutions and norms that govern us.”

I resent having to write political poetry; I would much rather write love poems, poems in praise of life, in praise of the Earth that bears it, poems of amazement for what is sensed and for what is imagined. Why I resent having to write political poetry is because I must oppose the institutions that govern us. Were those institutions founded on and governed with justice, with compassion, with reverence for life and the Earth that births us, I would be free to write in unhindered celebration and my political poetry would be in praise of those institutions and could be hard to distinguish from my celebration of life itself. Of course that would be a Utopia and being the humans we are, there would always be things to criticize, or ignore.

But the United States where I live and of which I am a citizen is much closer to a Dystopia and in that context, my poetry (or a great deal of it, though I also write much that is purely celebratory) must be overtly and strongly political in opposition to the injustice, the cruelty, the insanity that are the norms with which the nation (empire) is governed. My political poetry is the poetry of love outraged.

Among the many violations of human rights the U.S. government commits, one that most deeply touches me is its inhumane, unimaginably cruel, insane immigration policy. Borders are inherently political and just that, nothing more:

Borders are scratched across

the hearts of men

By strangers with a calm,

judicial pen,

And when the borders bleed

we watch with dread

The lines of ink across

the map turn red.

--Marya Mannes

they are crazy quilts

of pastel colors

(lilac, sky, lime,

lemon, orange, pink)

with arbitrary names and seams

with which we imagine the Earth

pretending to posses it

and call it ‘world.’

The Earth does not have seams

nor borders --

rivers and ravines, sierras, swamps,

canyons, jungles and deserts,

cascades and falls, seas yes,

but never borders.

Maps lie.

I was born on one particularly politically charged — the U.S./Mexican border, Cd. Juárez/El Paso. What is particular to this border is that the U.S. land north of the Río Grande, The Border, was stolen by the U.S. by invasion. Much of the population in this land is of descent and culture Mexican — it is our stolen land. Also, the majority of us are of mestizo blood, a mixture of European and indigenous blood. For us, the indigenous part, borders did not exist as such, the Earth belonged to no one, it was everyone’s.

My family came as the Mexican revolution of 1910 drew to a close in 1920, my parents but adolescents. So it is that I grew bicultural, bilingual between and participating in two distinct cultures. My parents always insisted that we preserve our Mexican culture and the Castilian tongue at the same time that we learned English. It was not always easy. The U.S. culture is little tolerant of the foreign and insists that the immigrant assimilate. In school we were punished if we spoke Spanish in the classroom or playground and many of us felt obliged to defend our own names. Prejudice in the society in general is great. Many parents permitted their children to speak only English to protect them from the effects of this prejudice so that they could advance economically and socially. The cost of assimilation is great.

To an Old Woman

Come, mother --

your rebozo trails a black web

and your hem catches on your heels,

you lean the burden of your years

on shaky cane, and palsied hand pushes

sweat-grimed pennies on the counter.

Can you still see, old woman,

the darting color-trailed needle of your trade?

The flowers you embroider

with three-for-a-dime threads

cannot fade as quickly as the leaves of time.

What things do you remember?

Your mouth seems to be forever tasting

the residue of nectar hearted years.

Where are the sons you bore?

Do they speak only English now

and say they’re Spanish?

One day I know you will not come

and ask for me to pick

the colors you can no longer see.

I know I’ll wait in vain

for your toothless benediction.

I’ll look into the dusty street

made cool by pigeons’ wings

until a dirty child will nudge me and say:

Señor, how mush ees thees?

(New Mexico Quarterly, Vol. XXXI no. 4, 1962; author’s copyrights.)

Too much, it is too high a cost. But to survive much is risked and much is lost. One rarely immigrates by desire but almost always by necessity. Historically the majority of our people who emigrate to the U.S. are poor, mostly farmers who come to work for very low wages, long and hard hours, under abysmal conditions, many illiterate or with little schooling, many speaking indigenous languages. They come without documents and often bring their families, children of very tender age, infants many. These children still undocumented have grown to be youths in every way U. S. except in citizenship, many speaking and writing only in English, many students in colleges and universities.

And now, the president of the U.S.A., President Trump (named among ourselves with the not very affectionate nickname Pres. Trumpet-mouth), racist and fascist, ignorant, arrogant, and heartless to the hilt intends, with the backing of his ilk, to expel them to their countries of birth, countries strange to them, countries not theirs — Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and many more. They are called Dreamers, soubriquet originating in a plan of the previous president, Pres. Obama, to protect them.

Our Dreamers

The country that casts out

for lack of documents

its dreamers

wounds itself.

What other land do they know?

What emptiness would they leave

in the consciousness,

in the hearts of the people?

It is to tear the scales

from justice, to put out

the torch of liberty.

It would be as if the eagle

with its own beak

and its claws lacerated

its own heart

already poisoned by cruelty.

Of borders and walls

dreams and need

know the same

as do the butterflies and the birds,

the smell of the flowers.

If we do not protect

our dreamers we lose

our souls and our dreams.

(Overthrowing Capitalism, Vol. 4, Hirschman, Jack et al., editors, 2018 San Francisco; author's copyrights)

With the ascendency of Pres. Trumpet-mouth, the emigrant has been demonized. The president has called them rapists, murderers, thieves, especially the Mexican, Central-American, Latin-American emigrants (and also terrorists the Moslem emigrants.) Fascism, racism, nationalism, and hate are patent and have been normalized in the U.S. political discussion. But we have to say it clearly --

To Say It Clearly

The fools say

that we come as beggars

stomachs empty, empty hands

to take what already

their own scoundrels and knaves

have stolen from them.

Yes, we come hungry

fleeing violence

to where the riches

of the empire are concentrated

but with hands full

of our crafts and labors,

hearts full of dances and of songs,

with our cuisine rich in flavors.

We bring soul to a soulless culture;

we bring the rainbow

and they prefer the grayness of their fear.

They insist on building walls

when there is need of bridges.

The border has been militarized and has been made a battle front. And Trumpet-mouth insists on building a great wall through the entire border between the U.S. and Mexico at a cost of approximately 70 billion dollars and 21.6 billion dollars to maintain. And foolishly insists that Mexico pay for it. But a price cannot be placed on the suffering that it has caused, that this policy causes. Emigrants are apprehended and jailed, mothers, fathers separated from their little children, many of them infants, the children put in separate jails, scattered, sent far away. And even though the courts have declared these acts illegal and demanded that families be reunited, still they have not been reunited and children have been lost. The cruelty, the suffering wounds the imagination.

So Kind Is the Moon

The full moon slips

through the bars of the jail

of the children

to gather their sobs

in her apron of light

and carry them to their parents

in the jail for adults

and bring the laments and blessings

of their mothers, their fathers

back to the children.

The moon is so kind

that it does not deny its light

even to the evil dealers in anguish.

So kind is the moon.

And what grave needs motivate these fathers, mothers to risk so much to emigrate to the U.S.? They come to where the wealth of the empire is concentrated fleeing the poverty and violence of their countries caused by U.S. policy:

Free Trade treaties that have been disastrous for the economy of Mexico, the cynical War Against Drugs that has brought atrocious violence to Mexico, the Mérida Accords that have militarized the government of Mexico and made it more violent. But it is not only Mexico; it is thus in all Central America and parts of South America. The powerful U.S. supports abusive governments that for the benefit of the rich keep their people in poverty and violent repression, selling their lands and natural resources to U.S. and global foreign enterprises. And those who resist and defend the Earth (a great part indigenous and women) are tortured and killed. A case representative of many, many others throughout the Americas is that of Berta Cáceres of Honduras:

For Half a Millennium and More

to Berta Cáceres

and to all the martyrs

of the Americas

killed defending the land

For half a millennium and more

we have died defending

the land, the forests, the rivers

from foreign invaders

blinded by greed,

crazed by profit

in bloodied coin.

We have suffered traitors

Infected by that madness

that for that same coin

sell their own gods.

Our bones sow the earth,

Our blood waters it,

and the sacred corn

sometimes tastes bitter to us.

But we go on struggling

and our bones and our blood

will grow a new flowering world.

Let us name it for what it essentially is: the economy of empire, Capitalism and its policy, an economic system based on two things: the treatment of the Earth solely as a deposit of raw material to be exploited and the enslavement of labor to convert that raw material into consumable products at low cost to sell at great profit for the good of the few. It was nothing but this that impelled the conquest of the Americas.

(Of the religion that for a long time had made itself the tool of the state and justified slavery and even genocide, I will say nothing, nor of the opposition within it that now comes to us as Liberation Theology.) Because the U.S. is the largest empire today and its president a modern Caligula, it is easy to make it the only villain, but this happens through the entire world. Unbridled Capitalism leads to fascism and we see this across the world today. The wars and tyrannies almost all caused by Capitalism displace a great number of people fleeing poverty and violence in order to survive. Migration is one of the greatest problems of the day notwithstanding that humanity has always migrated since its origins in Africa three to two hundred thousand years ago.

Migration

What does the butterfly know of borders?

What does it know of flags?

It crosses a whole continent,

movement its inheritance.

So it is with us,

migration our heritage

of years, of centuries, of millenniums

before history was

and we formed myths within the brain.

Our steps made of blood,

of tears, of laughter, and of sweat

mark our eternal search

for home signaled by the God,

or the eagle eating a snake,

or who knows what arbitrary signs.

But uncertain are our abodes --

home is the round and seamless Earth;

we circle it and if country we venerate

it is pretension, a myth, a lie --

we seek shelter, food, freedom, life.

Down with borders, down with flags

for if there were justice and peace

we would not have to so much roam the Earth.

I was born in, live in, am a citizen of the United States of America but more than anything I feel myself a citizen of the world. My loyalty is to humanity to which I belong and to the Earth that bore us and sustains us. My U.S. and Terrestrial citizenship obligate me to view my country, the world, and humanity critically. But if I have painted my country in somber hues it is not entirely a true portrait. Many, many U.S. citizens are not racist, nor toxically nationalists, nor unjust, nor cruel, nor capitalists. And many are the problems of empire and I have focused only on migration. Very great is the resistance against the forces of fascism, great is the compassion and the desire for justice. Many cities and even states have declared themselves Asylum to protect the undocumented immigrants refusing to collaborate with the federal police in the persecution of immigrants. Daily there are demonstrations at the doors of jails, the border, the airports, the government buildings, the streets in support of the immigrants. There is a great struggle between the forces of fascism that control the government and the democratic forces. We are in a crisis and the times are fearful.

As for me as an old man and a poet

I Tell You

I tell you that I am tired

of not being able to turn my back

on the injustice and cruelty of the world.

I would like instead to tell you

what the alder and the redwood,

the rock in the stream made smooth

by the soft or rough touch

of the water tell me.

I would like to tell you the tales

of the lizard and the butterfly,

sing you the quiet songs

of the honeysuckle and the rosemary.

I would like to write poems of love

to the Earth, to life, to you.

But I cannot turn my back

to the injustice and cruelty

of the world that causes

such pain and suffering on the Earth.

My verses of rage and protest

are also poems of love,

of a love betrayed and wounded.

© Rafael Jesús González 2018.

Rafael Jesús González es Poeta Laureado de la Ciudad de Berkeley, California/is Poet Laureate of Berkeley, California. Por décadas, ha sido un activista pro la paz y justicia usando la palabra como una espada de la verdad. For decades, he has been an activist for peace and justice, wielding the word like a sword of truth.

Life Along the Border

This trio of short stories tied for first place in the 2017 Writing Contest sponsored by the San Miguel Literary Sala, A.C., located in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico.

This feature first appeared in Somos en escrito on February 23, 2017.

The Spirit

We lived in a string of lean-tos behind an old service station next to Emilio’s Bar. All the families living here were just like chickens, going to bed at sunset, not because nature dictated our clocks, but because any light in a one-room hovel alerted the migra that mojados who had crossed the Rio Grande in the dead of night were nesting here.

A four-year-old at the time, I was sleeping on the floor on the soft, red blanket that was my bed when late one night my grandmother flicked on the bare light bulb dangling from the ceiling. She stumbled in with our neighbor Victoria leaning against her shoulder. Victoria’s eyes were slits, her face ashen. My grandmother, who was a curandera, slid Victoria onto her bed and quickly ushered me out the door.

“Vámonos! Fuera!”

“What’s going on, huelis?” I whimpered.

“Shht!” she shushed firmly, her finger on her lips.

I had already weathered my share of immigration raids so when my grandmother demanded silence, I was a mouse playing dead. But my body shuddered when I heard dreadful groaning coming from inside our shelter. Victoria was in agony. Was she dying?

The full moon that loomed over the large mesquite tree across the alley was a gray skull baring its ugly teeth at me. I could not bear to look at it so I sat on the cracked sidewalk, chin on my knees, staring at the alley and trying to ignore the wailing. It seemed like hours before my grandmother stepped out carrying a bucket filled with foul-smelling water that she splashed onto the alley. The water stained the gravel an eerie gray in the moonlight.

I grabbed her skirt and pleaded, “Can I go in now, huelis? Please?”

“Cállate, niño!” she uttered, shoved me aside, and rushed back in. Now I was terrified. My huelis loved me. She had never treated me like this.

Victoria began screaming: “No! No!”

Then I heard sobbing.

I rushed to the door, hoping I could sneak a peek. The adults inside started arguing then the light seeping through the cracks of the wooden door went out, the rusty doorknob squeaked as it turned, and Victoria’s husband stepped out carrying a dark bundle followed by my father and my grandmother. My mother called me back in and put me to sleep. The hard wooden floor was humid, giving off a dull musty odor.

Later that night I woke up screaming when I saw a translucent, blue figure floating through our shack. My grandmother ran to my side and picked me up in her arms. She brewed an herbal tea for me to fend off bad dreams and cuddled me on her lap, rocking me to sleep.

Dawn came and my grandmother and my parents acted as if nothing had happened. No matter how much I pestered them, they dismissed my questions about the night before. We moved out of the area when my father landed a good-paying job as a plumber, but images of that eerie night were indelibly etched in my mind. My grandmother always assured me that my childhood imagination had conjured up this dark tale. It was not until she suffered a stroke that placed her at heaven’s door that she decided to rid herself of her earthly burdens.

“Te acuerdas…de..de..aquella noche,..mi’jo…” she said, her voice faltering as she recounted what had happened that strange night.

Victoria had had a miscarriage, she said. They didn’t call the priest to give the child his final blessing because the priest was an Anglo. They were afraid he would call the migra. They had buried the child in the empty lot behind Emilo’s Bar, and my grandmother had said the final prayers. Her dying wish was that God would forgive her.

Her revelation was jarring. That lot with its scraggly bushes once was my favorite place to play hide-and-seek. It was also my sanctuary whenever I got in trouble with my parents. I had carved out a small hideout in the brush where I found solace. Somehow I felt like I had a friend there to console me. I lost that little haven when the garage owner turned that lot into a place for oil changes, and the earth gradually darkened to a pitch-black. The image of a baby drenched in this waste haunted me. My soul yearned to pay my last respects.

I went to my hometown, which had grown into a small city with a cluster of ramshackle cottages on its outskirts. Ankle-high weeds covered the backyards there with well-worn paths leading to sagging outhouses; kids were playing stickball in the alley. I felt at home. But my old barrio was quite a ways from those shanties. I finally reached the street where we once lived. The panaderia at the street corner that once filled the air with the sweet scent of cinnamon from freshly baked pan dulce had been supplanted by a dry cleaner. The garage and the bar had been leveled, replaced by a large cinderblock building. A grocery store occupied the portion of the structure where the garage used to be. Next door, there was a sign that read La Señora Adivinadora with a large Tarot card taped to the windowpane that showed Persephone, the high priestess sitting on her throne between the darkness and the light in front of the Tree of Life.

I walked into La Señora’s place, which had a glass counter with a collection of talismans mounted on shelves and a black curtain separating the small front room from the rear. The curtain slid open and a somber woman with dark brown eyes and black flowing hair strolled out. Around her neck hung a gold chain with an image of the Virgen de Guadalupe set in mother of pearl.

“Buenas tardes,” she said as she walked to the counter. “Would you like me to read your fortune?”

I looked past her to the rear of her unit, which stretched all the way to the alley. Concrete now covered the former back lot of Emilio’s Bar.

“Come into my reading room back here,” she said. “A special spirit resides there that guides me.”

I pursed my lips.

“I know,” I nodded as I closed my eyes.

The Stetson

Winter unleashed heavy downpours that battered noisily against the windowpanes. Gonzalo tossed and turned. His older brother Maurilio was snoring exceptionally loud tonight. It was a nightly ritual that began with hoarse guttural mutterings that would then dull into a drone before Maurilio would finally slide into a deep sleep. The steady drip of the rainspouts added to his insomnia.

With Maurilio’s snore down to a whisper, it became the mouse that prevented Gonzalo’s slumber. That vermin had been harassing the family for weeks despite the traps that had been set throughout the house. He heard it scratching at some package in the kitchen cabinet. He listened intently, hoping to hear the loud thump that said: This rata is dead meat! When it was satisfied with its treasure, the mouse scurried down the hallway, its claws rasping against the wooden floor, avoiding all the mines scattered on the floor. It was quiet again. The chiming of the clock told him it was midnight when his father’s truck pulled into the driveway. The pickup door opened and slammed shut. He heard his father come in the front door. His mother was still awake.

“Hola, mi amor, I’m home,” he said jovially.

“Where the hell have you been?” she asked.

“Is that any way to greet your viejo?” he asked.