Chicano Confidential By Sonny Boy Arias (2018) Recently, someone turned to me and said, “You’ve got a lot going on in your life right now, don’t you?” and in a micro-second of reflection I thought, “Not any more than normal,” and then the reality of my situatedness of daily life sunk in. “Yes,” I thought, “I guess I do have a lot going on.” By this coming June, I will have 8 grandchildren (including a set of twins), as everyone is pregnant (we currently have 4 male grandchildren). I am currently searching for solutions to place my father in long-term rehab care in San Diego and my mother’s dementia is progressing so rapidly that I can hand her something and she will place it immediately in the proverbial Black Hole. I am leading a major policy shift at my university, while acting as lead academic planner for our University’s 25th anniversary, and I have made arrangements to take our entire family to Maui for the greater part of the summer, oy vey! I’ve even reached a point where I conducted the preliminary math demonstrating that I may be retiring as early as this summer. These events were for the most part not unexpected as I am an old scuba diver and I always “plan my dive and dive my plan,” but I have to confess: no matter how prepared one is, Father Time has a way of sneaking up on you and tapping you on the shoulder. It seems that time, numbers and my personal philosophy make up the mainstay of how I construct my reality in daily life at least for the onset of this coming year. I didn’t think my goings-on were observable, nobody ever really does, that is, until somebody does make the observation, “You really have a lot going on right now, don’t you?” We all believe that most people don’t really care about who we are or what we stand for, not really, for emotional and practical purposes. Daily life is way too complex for one to keep up with the energy it takes to truly care for others. I mean, doesn’t everybody always have a lot going on? It’s simply too much to keep track of what people are doing, thinking or facing. Why should my situatedness stand out, why now? Conversely, this is why I find most everyone quite interesting, everyone has a story, and every story is unique and in turn interesting. Said differently, everything may in fact be observable but what is interesting for the day or even for the moment is a topic of social inquiry all on its own; it is phenomenological in this way. It’s as though my Self (in a social psychological sense) is evolving with every social interaction; how can it be perceived any other way? While I am keenly aware of such evolution, I’ve never felt the evolution of Self the way I do now. What better way to measure one’s situatedness than to compare your time (like, your time left on this earth) against the backdrop of the endless situations that come up in everyday life? Everything is quantifiable such as the number of strokes of genius, impulses, how many grandchildren, even the number of heartbeats in one’s life, you can count them all. Again, the statement directed to me can be directed to you: “You’ve got a lot going on in your life right now, don’t you?” At first, it can only be examined existentially because it evokes feelings, often deep feelings depending on the situation at hand. I will say there are markers along the way, some outright signs along the way you might say that are not only directive, but, all at once full of symbolic meanings. Much like the radical empiricist William James, my tendencies are to ground what I say theoretically in observable examples, including those found in my own life. At the onset of this past summer, I observed two massive (I mean massive) chunks of glacier each the size of five football fields slip into Glacier Bay, and this occurred within 12 minutes of each other. I video-taped the second slide, but haven’t mustered up the courage to view it again as it really rocked my world. Having been taken by surprise, I was all at once mortified to the core of my being, my brute being that is, I honestly still can’t seem to shake the feeling. I wasn’t fearful of a tidal wave effect or anything of that sort, frankly I didn’t know what it was I was feeling. It wasn’t until weeks later that I came to the realization that I was in shock and this triggered my sensibilities beyond my control all at once, changing my human condition, forever. Likened to Ludwig Wittgenstein’s “white sheet flashes” to massive sheets of sliding ice were simply too much to handle all at once. How else can I say it except that “It scared the hell out of me!” I wasn’t aware of the full impact it had on my psyche until much later. It was as though I was completely caught off guard by a sensation so overwhelming my sensibilities were shut down by natural defense mechanisms and as a result, I switched to autopilot, not allowing myself to feel the sensations that were so overwhelming. It was one of the greatest contradictions of my life. While I have always enjoyed living and dwelling in contradictions, suspended existentially so, enjoying being at the helm of a sailboat with a broken rudder in a full gale storm, this was a test of the tempest, “nor'easter” you might say. I imagined the sky ripped open by a giant Russian god-like philosopher, yelling down to all of humanity: “You all have ruined the earth; look at her now look, at Gaia (Mother Earth). The massive sheets of ice slipping into Glacier Bay are her tears crying to let her loose, to let her heal herself the way only she can do. You (humanity) need to step aside and let nature (Mother Earth) take over and heal herself, she has taken care of herself for billions of years, well before humans arrived, for Christ’s sake step aside!” This was it! This was the penultimate contradiction of my life and it caught me off guard, I’ve been sensing this ever since witnessing Gaia cry; it was like Mary, Mother of God, crying for her son and for our sins. Last month, in my capacity as the keynote speaker and a Distinguished Alum at UC San Diego’s 50th year celebration of its graduate division, I presented myself as a well-trained scientist that had tried on various rationales that might help me mask the realities we are facing in American society today – one is global warming. I argued that during current times it is quite difficult to perform critical objective scientific analysis because the average person on the street does not understand science and their thoughts are based on what they gather from quip-like political remarks they hear on television, on the radio or read in pop-ups that are not scientifically based. The physical condition of Mother Earth is in the back of my mind, even more so than is the fate of humanity, she needs real help beyond what I have to offer and I have offered more valiant efforts than most as evidenced by my work in convening world-class scientists in Big Sur. At the core of my being, I’m keenly aware that everyone tacitly knows but doesn’t want to say out loud the unspeakable truth: “We [humanity] have systematically ruined the earth due to greed and to self-preservation beyond the type designed for us by nature. We somehow got off track and at the cost of forsaking others or even contributing to the social good have designed distractions into our realities so great that we consume much more than we can play out in useful ways in one lifetime. This behavior has driven humanity far beyond the tipping point for any possibility of ecological reconstruction. There is no going back; the massive chunks of ice falling by the minute in Glacier Bay don’t suddenly re-attach themselves, they don’t grow anew like frozen crystals, they simply melt away like islands of meaning that only few can understand, because people don’t take the time or have the time to save them or Mother Earth.” People remain distracted seeking refuge in the Google-god thinking they have an understanding of every situation, every problem and every subject matter. From a scientific perspective, it’s simply annoying to constantly hear interpretations of a Google sort from those who have little understanding of deep levels of predication. “Just Google it,” they say, with no understanding that the rhythm of their personal algorithm shines only a subjective light that cannot (will not) allow for objective truths. We live in a world where perception is everything and scientific truths no longer ring of truth. We are experiencing the advent of new curious concepts like “fake news” or “fake truths” and so what we find is small children questioning thousands of years of scientific truths the scientific method, models and paradigms based on knowledges that were built on each other, not that we suddenly postulated as a tweet or felt sense and nothing more. The philosopher Aristotle believed that “seeing is believing” although he didn’t live in a world of social media in the same manner as we do today. He did not take into account that for political reasons people would begin purposefully altering video and pictures for political reasons. This was not part of his awareness. Said differently, whether you believe in global warming or not, whether you practice science or fake science or fake news, I know what I saw and experienced in watching Gaia cry sheets of ice. This truth cannot be denied, I heard it, I saw it, I even smelt it. It’s like listening to your aged mother who is hard of hearing trying to order her prescriptions over the phone: “Can you please speak up,” she says. “I can’t hear you, please speak up.” It’s a truth you can’t deny, it’s not “fake,” just as in the gym, the barbells don’t lie—they are in fact heavy. Sir Issac Newton observed a basic truth “What goes up must come down.” Watch video replays of when you were young as they capture a picturesque younger Self about the way things once were and sometimes these are difficult to watch because they capture a truism: “You are [today] what you once were [yesteryear]. The unforgettable sound of cracking ice is so memorable; it is in fact plaguing to my senses, I will never forget the sound and yet this phenomenon becomes the mainstay marker for the rest of my life, placing me on a hermeneutic spiral to enjoy in a rather disturbing way. For me the sound or old reflections are evocative, poignant even melancholy; they linger and contribute to the way I construct my reality in daily life – how else can I say it, except to say it the way it feels, this becomes my situatedness, this becomes the foundational springboard for the evolution of my Self (in a social psychological sense). So in this way, yes, I am just like you, I do have a lot going on in my life, for many it appears I am preoccupied with the end of the end of things: objects, relationships, even perspectives or paradigms for looking at scientific discoveries. Things change, science changes the way we view realities through scientific discovery not through “fake news” or “fake truths.” It’s the eve of yet another year to come and a year gone by even at a more precipitous pace than the previous one. Yes, I sound like my parents and uncles who constantly remind me, “Life is short.” Yet I remain baffled at what is inevitably to come, this year, unknown yet seemingly felt in my soul. What new vulgar circumstances (even rollicking vulgarity or playful exuberance) will give birth to my story writing for example? As I grow older, words, it seems, sit on ideas with uncanny ease and make more stories seem inevitable, I never know what is coming out of my imagination next. I do however remain convinced that as Einstein puts it, “Imagination is more important than knowledge,” which, by the way, is the trick for scoring at the highest levels of IQ tests and college entrance exams. “Teach your children well.” Now headed for quasi-retirement, the fictional stories I started writing in the form of “science friction” afford me a separate life, a “separate reality” as my old friend Carlos Castaneda used to put it, and new relations. I’m aware of my lack of formal training in creative writing, yet it actually becomes the very reason whenever I go to contemplate a “creative” work for pleasure. I’m fine with the fact that my stories will surely not be on the Best Seller’s List nor a Pulitzer Prize winner for these authors always lack soul and only write for the prize. They are in fact creatively boring, what one might typify as “tragicomic solipsism.” Frankly, I’m always fascinated at how boring prize-winning authors can be in real-life. Even so, there is almost no one I can call for honest advice, “Your stories are great” they say, with no proof or affirmation. It’s not difficult to realize how I cause a new deviance disavowal because I know they didn’t read my writings, yet feel the need to tell me they did, hey, no problem. I firmly believe people trained in creative writing practice linguistic calisthenics; a lot of words, without soul. I understand how the book writing world works, people simply prefer living the illusion, and again, perception becomes everything; therein lies the organic disconnect. In this spirit, I have even come to believe in the “fish stories” I have to some extent imagined and I see this as a good thing inasmuch as I have continued mindful activities and exercises that contribute to the evolution of my prodigious memory that allows me to recite my finished stories verbatim. I became aware of this ability many years ago when seated in a hot-tub next to a distant relative at a family reunion held at the Rosarito Beach Hotel. I told her the story of how I was once attacked by a wild-boar on Catalina Island and she did not believe me until the next day when we were joined by her husband whom I shared the story with as well and she observed, “Sonny Boy (my nickname), I didn’t believe you yesterday but I do believe you today because you told the story in the same way word-for-word.” It is the case that I practice the art and science of writing like I talk and talking like I write, plus I want to defer atrophy of my brain as long as possible. Most people don’t see the insight my stories can bring as they say, “his silly little stories;” they are all psychoanalytic and often viewed as “irritatingly clever.” I think more about the future and the future I am already starting to miss. I remain eager to see how my personal buoyancy plays out in a hopefully different economic and emotional climate as I reach my later years. The way I see it, psychologically I should be happy, financially I should be set. Don’t forget, a scuba diver “plans his dive and dives his plan,” so I have a plan. But will an unexpected “four-alarm fire” surprise me, will I find it exhilarating (like being shot at), will I have the capacity to turn a nightmare into an insidious experience, at the very least a cheap thrill. If anything, my trained anticipation of the unexpected has always turned to a mission of good times. I expect to look back at any “urgency” and think “courage, after all, wants to laugh.” You can’t take life too seriously as it wasn’t meant to be that way, yet so many of us cannot see it any other way as evidenced by people who take themselves too seriously. It is for this reason I continue to amuse myself to death. I’m having a hell of a good time, by design. Life is for me an intellectual game. The allusion and/or insinuation endorses my serious refusal to be serious. I see every idea as inescapable from the link to the evolution of SELF, not vain, not self-defeating, not even a linguistic construct, but artistic. It is through this paradigm for looking at storytelling that I simply want to show those who indulge in my stories how to live a fulfilled and meaningful life and to become less alone inside in a world with inescapable ways of contributing to alienation, Karl Marx’s greatest fear. Said differently, through my stories I want to help people feel life, and remain more than arm’s distance from being-bored-of-being-bored. Hence, if you are going to mistake your wife for something mistake her for a hat, a nice black hat (a la Oliver Sacks) and enjoy it, don’t get freaked out by the experience. It’s like taking LSD. Timothy Leary use to say, “Never have a bad trip, learn from it, enjoy it as you will never forget what you learned.” What I believe is that there can be optimism within one’s personal despair, elation of a curious sort in its anomie. More than ever I feel like a paradoxical character with an outsized passion, repression and expression: twin causes of complication, harmony and disharmony with significant others who think: “He is such a nice person, a good father and great grandfather, yet there is something in him that keeps him from being completely decent.” I have to ask, “Do people not understand my aesthetic?” Years ago I wrote a book on fear and it wasn’t until now that I came to the realization that I write stories because I am afraid that the last thing I will write will be the last thing that I write. This is not paranoia as that would be fear of the unreal; my fear is based not only on real fear as evidenced by the stories I keep producing, but also by the body of original scientific knowledge I have contributed over time. I find in life amusing peculiarities that trigger epiphanies, continually! Maybe deep down inside there is the possibility that telling a story could lead to redemption of a sort, for what reason, I am searching, but perhaps it may be found in spirituality and values. So, this is what is on my mind on the eve of a new year. I’m curious to know what’s on your mind.  Sonny Boy Arias, a dedicated contributor to Somos en escrito via his column, Chicano Confidential, is a stone-cold Chicano, who writes under the general rubric of historias verdaderas mentiras auténticas–true stories and authentic lies. He has found this the most effective manner to convey his stories about Chicano life. Copyright © Arts and Sciences World Press, 2018.

0 Comments

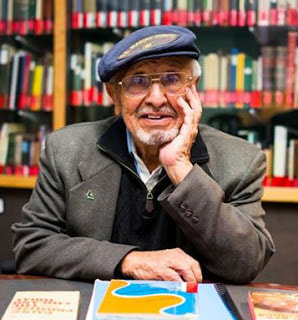

A Eulogy to By Armando Rendón A life-long friend and colleague, Felipe de Ortego y Gasca, has passed away today; he is now one with the universe as he was one with so many of us in life. Felipe invented Chicano literature because, as I see it, his studies into the early writings by Chicanas and Chicanos provided not only a scholarly basis for the field as a genre of American literature but inspired many of our indigenous-hispanic writers to put pencil or pen to paper, pick out letters for a manuscript on the old manual typewriters, and today tap out a poem or novel on a laptop while commuting back and forth from a job. We go way back to 1972, when an ambitious young man (I think we were all something like that then) named Dan Lopez got the idea for a print magazine he called, Nuestro. The project was ahead of its time and folded in a few years, but Felipe and I were recruited by Dan to help make the magazine go, Felipe as editor and I as a freelance writer and photographer. We struck up a friendship and kept in touch over the years. I learned much later that Felipe had dropped out of high school in 1943, yet wisely took advantage of the G.I. bill to get a BA at the University of Pittsburgh in 1948, then a Master’s degree in literature at Texas Western College in El Paso, followed by his Ph.D. in literature at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque in 1971. He eventually earned a post-doctoral degree in Management and Planning for Higher Education at the Columbia University Graduate School of Business’ Harriman Institute in 1973. It was when I launched Somos en escrito Magazine in late 2009 that we hooked up again. So much of what Felipe wrote about Chicanismo from the literary aspect had not been broadly circulated that he found Somos a perfect vehicle to inform a new generation, and I gladly partnered with him in publishing as much as I could of his stories and literary critiques. I intend to work with his wife of many years, Gilda Baeza-Ortego, a scholar in her own right, to reveal other works he might not have yet offered to us. Felipe’s early service as a U.S. Marine during World War II—a feature on his tour of duty that took him to China accompanies this eulogy to him—served him well in recent years when he battled a variety of illnesses, such as the shoulder replacement he underwent earlier this year. I had invited him last spring to join me and a couple other Chicanan writers for a panel on Chicano literature to be presented in Cuernavaca in early August. I knew he was not at his healthiest but how could I not first ask the father of Chicano literature to address a conclave of international scholars on his favorite topic? He had accepted my invitation in a flash, but as it turned out, Felipe’s health failed him and he had to cancel the day before his and Gilda’s flight to Mexico. For sure, only a very severe ailment could have forced him to bow out. The other two panelists, good friends of his as well, Rosa Martha Villarreal and Roberto Haro, and I stepped up to present his “Cuernavaca paper” on his behalf. (Click on the link to read de Ortego y Gasca's Cuernavaca paper: FelipeCuernavacaPaper) Felipe de Ortego y Gasca lived a long and eventful life, leaving among many other contributions to Chicanismo and society in general, a legacy as a visionary scholar. Who would have guessed that today we would have the breadth of writing by Chicana and Chicano authors, in every genre and on every topic. He invented the Chicano Renaissance so he himself deserves to be called a Renaissance Chicano. May you rest in peace, old friend. Armando Rendón is founder/editor of Somos en escrito Magazine. A Chicano Christmas in ChinaBy Felipe de Ortego y Gasca This is a story about a Christmas in China after World War II and how the world changed for me as a consequence of that Christmas. Hard to believe that almost six decades have passed since VJ Day (Victory in Japan, August 14, 1945) and the end of hostilities for World War Two. By Christmas of 1945 the war had been over more than four months, just after President Truman had authorized dropping an atom bomb on Hiroshima on August 6 and one on Nagasaki on August 8. I felt ancient at war’s end. War has a way of maturing youngsters, growing them up quickly. There is also a mantle of invincibility that cloaks the young, woven of equal parts of arrogance and ignorance, strands of curiosity, and large patches of naiveté. It’s a wonderful time of life: full of joy one thinks will last forever; full of agony that seems interminable. I was a Sergeant of Marines then, filled with the exuberance of victory marking the end of a life and death struggle between the forces of good and evil, a struggle that claimed 50 million lives worldwide. I was 19 years old that August and the fates had kept me from harm thus far. Just two years earlier, on my 17th birthday, I had enlisted in the Marines, during the dark, grim days of the war when victory appeared implausible and the fate of democracy hung in the balance. The San Antonio of 1941, where a branch of my mother’s family settled in 1731, was a place of “brown blood and white laughter” as I wrote in a poem years later, remembering the city’s segregated schools and its English-only rules. Though the war transformed the city economically, a different kind of war would vanquish the barriers that had made San Antonio a divided community and strangers of Tejanos in their own land. At war, Tejanos showed their mettle, Boys became men. The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) suspended its annual conferences for the duration. On the home front, Mexicana Americans built planes, subs, and gliders; handed out donuts and coffee to America’s youth training at Fort Sam Houston, Kelly, and Lackland Air Force bases in San Antonio. Many became air raid wardens. On the West Side, Tejana mothers placed gold stars in their windows. On the day of infamy, I wondered if I could pass for 17, hoping the war would wait for me. I tried to enlist in the Army in 1942 but was turned away because I was too young at 15 for military service they told me even though the country was desperate for troops. I got as far as the physical before I was found out and turned away with an admonishment veiling a smile and an encouragement to try again next year. Did I know, they asked, that I had flat feet? By next year, I thought, there would be no glory left. But I waited, toughing out the 9th grade of school. I should have been a Junior but instead I was a high school Freshman, two years older than my classmates because I had repeated the 1st grade and had been held back in the 4th. I started public school as a speaker of Spanish in segregated schools and didn’t improve until I made it to the 5th grade. In January of 1943 I tried enlisting in the Navy but was rejected because of “color blindness,” not because of my age. When I turned 17 that year, I tried the Marines, color blindness, flat feet and all. They accepted me, and after boot-camp at Parris Island, South Carolina, I was assigned to the Marine Air Station at Cherry Point, North Carolina, from where I was sent to the 8th and I (Eye) Marine barracks in Washington, DC. From there I was ordered to the Marine barracks at Air Station Quantico, Virginia, from where I shipped out to the Pacific. After a stop at San Diego and Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands, I was part of the tail-end of the last campaigns in the Pacific. When Japan surrendered, American GI’s in the Pacific were grouped into those who had earned sufficient points for immediate return to the states and a victor’s welcome, and those who didn’t. Wartime service was after all for the “duration” and the war was not officially over until December of 1946 even though the fighting had ended more than a year earlier. Troops not returned to the states were massed into a force of military occupation for Japan and those headed for mainland China as an army of liberation to disarm the Japanese troops in China and to oversee their evacuation. China had been occupied by the Japanese since the 30's and at the outbreak of hostilities had interned the 4th Marines who had been stationed in Shanghai. China would be freed at last. The hop from Okinawa to Shanghai was short. On that rain-washed day I did not know my journey to China would mark the beginning of my search for America. An early day harbinger of Battlestar Galactica, the rag-tag fleet of American ships trailing up the Yangtze River toward Shanghai was heralded with cheers of jubilation and gratitude by the Chinese. “Ding hao!” they shouted. “Ding hao! Good, good!” But that mood quickly soured when the hive of sampans crowded the spaces between the ships and the smiling Chinese held out their hands for some token of largesse signaling our arrival. What turned the scene ugly was when the Captain of the U.S.S. Monrovia ordered the fire hoses turned on the Chinese clambering up the sides of the ship trying to get on deck. The Chinese were eager to greet us, but that greeting was met with disdain by those Americans who saw the Chinese as nothing more than “gooks” and could not differentiate them from the Japanese. The force of the water hoses sent the Chinese back into the mass of sampans, some of them falling into the water through the spaces between the flat dugouts. The scene became a melee when the sailors decided malevolently to aim their hoses at the people on the sampans. The Chinese were bewildered. Why would a liberating force treat them that way? Chinese women screamed as their babies were flushed out of their hands by the force of the water from the fire hoses. What should have been a celebration became a melee of confusion and grief. That was not our finest moment. Those images have remained with me ever since. Little wonder we lost China to Mao Tsetung in 1948, forced to take our troops to Korea. I was gone by then. I left China in 1946. But the specter of that moment did not deter me from savoring the experience of being in China, the land of Cathay, of Marco Polo and Genghis Khan. The Yellow Sea washing against a land already ancient when the sailors of Colón flitted from fleck to fleck looking for Cipango (Japan) was not yellow but emerald green in the time of my youth when all my dreams were green. Years later I would realize what a profound effect that experience in China had on me. My stay in Shanghai was brief. My outfit moved on. I was assigned to temporary duty with the 6th Marines in Peking and Tientsin. I was posted to duty with Marine Air Group (MAG) 24, First Marine Air Wing at Tsingtao, a key airfield in the Japanese occupation of the Shantung Peninsula just across from Korea. Tsingtao is a port city and at war’s end was once more bustling with the hum of international trade. In Tsingtao (which sounded like Chingdoh) I was looked upon with puzzlement. Was I an American Chinese? A Migua Chinee? They had never seen a Mexican American before. Yes, I nodded, good-naturedly. “Ding hao, ding hao!” Good, good! the Chinese responded with smiles of approbation. Was I the first Chicano in China? No. Twenty-five years later in El Paso I would meet a Chicano, Cleofas Callero, who had been a China Marine in the years between the World Wars. There were probably others before him. Some 30 years later, Carlos Guerra, the journalist from San Antonio would travel to China. So would Patricia Roybal of El Paso and her husband Chuck Sutton, heir of the publisher of The Amsterdam News. And in the 80's Rudy Anaya, the Chicano novelist, from Albuquerque, New Mexico, would venture to China and record his impressions in a work entitled A Chicano in China. My affection for the Chinese was regarded with mischief as word spread that the Sarge was a Chink-lover. Fortunately, hierarchy and rank are powerful investitures in the military, especially the Marines. The troops may have disliked my affection for the Chinese but they took orders from me, like them or not. Every day I dressed down some troop for dissing the Chinese. They were not our beasts of burden, though we employed them on the air base as if they were. In China, American forces rode roughshod over the Chinese, acting more like Alexander’s Macedonian soldiers than emissaries of freedom. The Chinese quickly saw me as a friend. I was invited into their homes. I became good at ping-pong. I went everywhere with confidence. American troops in China, as almost everywhere else, did not carry currency. Instead we were issued scrip—paper money backed by the U.S. Armed Forces. Chinese money was out of the question. With inflation, Chinese money was almost useless. GI’s collected it as souvenirs or for prospective wallpaper. The brothel of “white” Russian women in Tsingtao preferred goods for their services. Cigarettes were most preferable. Chinese merchants accepted scrip which they exchanged for currency. In Peking, Chiang Kai-shek was struggling to stabilize the monetary woes of the country. One evening, not long after I arrived at Tsingtao, the base responded to a fire alarm in the city. The British Officer’s Club had caught fire and needed help in putting out the blaze. The fear was that the fire would spread into the city and become harder to control. From the airbase, three runway fire trucks with foam screamed into the night roaring toward the glow of the fire in the distance. As NCO of the day, I was responsible for dispatching the fire trucks. The old China Marines used to tell stories about Chinese fire drills which I didn’t understand until the night of that fire in Tsingtao. What confronted us was both risible and tragic. Attempting to put water on the fire were Chinese firemen struggling with old-fashioned wheeled water pumps. One man pumped while the other directed the hose barely trickling onto the fire. The Chinese firemen smiled politely as they greeted us. We ushered them out of the way, and quickly funneled a sheet of foam over the fire. We had arrived just in time. Though the Chinese firemen could not have contained the fire, their efforts had given us sufficient time to get there and to put the blaze out. I recognized that the caricature of Chinese ineptness was compounded by their lack of available technology. Mao Tsetung recognized that lack also which is why he launched the Chinese Revolution. China had to enter the modern age despite its legacy as a victim of colonialism. The week before Christmas some of the men in my troop wondered if we could find a Christmas tree in the hills beyond the air base. “Whadaya think, Sarge?” “Sure, why not?” We weren’t prohibited from going into the hills, though we were counseled to be careful. The Chinese Communists had been massing in the North and there were reports that some of their units were heading south. I checked out a truck from the motor pool and with a patrol of men headed toward the rise of hills some four or five miles west of the base. Once there, we headed off-road toward a clump of Chinese pine trees and settled on a good-sized tree that we chopped down quickly and loaded onto the truck. As we were ready to mount up and head back to the base, one of the men called out, “Sarge, take a look!” Coming out through the trees were a number of platoons armed with carbines and wearing drab uniforms with no insignia. The one who seemed to be the leader came up to the truck, surveyed it, walked around towards the front where I was standing, all the while with his finger on the trigger of what looked like a rapid-fire carbine. His men stayed at a distance but with fingers at the ready on the triggers of their weapons. We had brought axes not weapons. I was the only one with a sidearm. I beseeched my men to stay calm. I could see they were nervous. But they were seasoned men. I mustered a subtle smile as the leader of the hostiles acknowledged me and proceeded to inspect the cab of the truck. On the passenger side of the cab lay the book in Spanish I had been reading off and on for some time: La Vida Trágica, The Tragic Sense of Life, by the Spanish philosopher, Miguel de Unamuno. Picking up the book, the leader of the armed men who by that time we had all surmised were Chinese communists, asked: “Y este libro, de quién es? Whose book is this?” I was startled by the expression, little expecting a Chinese to speak Spanish, at that moment and in that place. “Mine,” I said. “Es el mío.” “Hm,” he murmured, pursing his lips, studying me intently for a moment. He put the book back on the seat of the cab and mustering an equally subtle smile motioned his men back into the anonymity of the woods. Before disappearing into the trees, the leader turned and with a most subtle smile, waved. I waved back wanly, relieved that the incident turned out as it had. “What was that all about, Sarge?” one of the men asked. “I don’t know,” I said. “I don’t know.” Years later I would know, years after I had acquired a structure of knowledge into which to fit that experience. One day, epiphanously, I understood the significance of that moment in North China and the Christmas tree incident of that December. By then the homecoming parades had all been held and the heroes all properly heralded. The United States was almost back to normal. Uniforms with plastrons of medals had been hung in closets for a day when they would no longer fit. I was ready to begin my search for America. The roots of that search lay in China where I saw “the others” and saw myself in them. Though I had grown up in a segregated society I had never thought of myself as “the other.” But the war changed me and the way I was to see myself in the context of the United States. I learned that no matter that Mexican Americans had won more Medals of Honor than any other ethnic group in America’s defense, we would have to fight far fiercer battles to secure for ourselves and our children the fruits of American democracy. Though I had completed only one year of high school, nevertheless on the GI Bill I went to college after the war at the University of Pittsburgh where in text after text I studied I did not find myself nor my people. I did not find my people in the texts I studied at the University of Texas either where I pursued the Master’s degree in English. They were also not in the texts I studied at the University of New Mexico where I completed the Ph.D. in English renaissance studies, American literature, and Behavioral Linguistics. And because I could not find Mexican Americans in those texts, my life’s work became a crusade for their inclusion. In 1947 the city of Three Rivers, Texas, shamelessly refused to bury in its municipal cemetery a Mexican American GI whose body had been exhumed in the Philippines and brought home for a hero’s burial. Adamantly the white city power brokers would not yield from their decision. At that point Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson approached President Truman on the matter and he directed that Felix Longoria be buried in Arlington Cemetery among the valiant of the nation. Out of that incident emerged the American GI Forum, a separate organization for Mexican American veterans, an organization I joined. Since then, numerous like incidents have necessitated creation of many separate Mexican American organizations. It didn’t need to be that way. Once, we were all brothers-in-arms. In my search for America, I have often thought of that young Chinese communist who bade me good luck in a language my country sought to strip me of. I have thought often of that China of so long ago. Once, I harbored thoughts of returning to China to look for that young man who had perhaps read Unamuno’s Tragic Sense of Life−in Spanish and who at that moment may have seen me not as a Migua Chinese but as a literary kinsman. Who was he? And how had he come to learn Spanish? Was he perhaps a child of a Chinese Communist who had participated in the Spanish Civil War of the mid ‘30’s and was now a Maoist? Hm? The question has remained pervasive for me during all these years. Thinking back—over the years—the gains have been worth the struggle. Mexican Americans did their part in World War II. And in subsequent conflicts as well as prior wars. This is our country, too, for we are in the land of our ancestors when this part of the United States was Mexico; and when it has called, we have served. But I’m still looking for America, in the nooks and crannies of those years since VJ Day, the end of World War II, and that Christmas in China.  Photo by Alicia deJong-Davis Photo by Alicia deJong-Davis Felipe de Ortego y Gasca was Scholar in Residence (Cultural Studies, Critical Theory, and Social Policy) and Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Philology and Cultural Studies at Texas State University System-Sul Ross. This memoir, which first appeared in the Alpine Avalanche, August 3, 1995, was presented at the Multi-Ethnic Christmas Celebration hosted by the Jernigan Library, Texas AandM University-Kingsville, December 6, 2004, and includes material from the author’s piece in 1941: Texas goes to War, University of North Texas Press, 1991. Copyright ©2001 by the author. All rights reserved. *Photograph by U.S. Marine Corps, http://www.qingdaonese.com/us-marines-in-qingdao-1945-48/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32891790 “La Poesía Política es esa que habla en oposición o apoyo, en crítica o justificación de las instituciones y normas que nos gobiernan.”Por Rafael Jesús González (Ponencia sobre poesía política presentada en el VIII Congreso y Festival Internacional Proyecto Cultural Sur, Montevideo, Uruguay, octubre 2018) Recientemente se me invitó a participar en un panel “¿Que es la poesía política?” con distinguidos colegas a quienes estimo mucho. Se nos pidió que consideremos si hay un género de poesía que es política y como diferiría esta de la poesía que ostensiblemente no fuera considerada política y si el mero acto de crear es en si político. Se nos pidió que leyéramos dos poemas nuestros y dos de otros poetas que ilustraran nuestro pensar sobre la poesía política. La idea era tener una discusión en mesa redonda y responder a preguntas del público. Nunca pasó. Se me pidió que iniciara la discusión; presenté mi posición y leí mis dos poemas, uno de Roque Dalton y el último poema de Javier Sicilia. Mis colegas completamente ignoraron las instrucciones al panel, dijeron esencialmente que el acto de crear era en si político y entonces tal era toda poesía y siguieron a leer de una gavilla de poemas que habían traído consigo. El evento se volvió en simplemente una lectura de poesía; no hubo discusión en mesa redonda ni tuvo el público oportunidad de hacer preguntas. Algo irritado dije que si el escribir poesía era en si acto político entonces no había nada que decir y que además no le podríamos llamar a un poema sobre un peral, o un cuervo, o el poema de Bashó sobre una rana o un poema de amor políticos en ningún sentido. Y con eso se cerró la conversación que nunca tuvimos. Por supuesto mis colegas sabían bien lo que fuera un poema político y cual no y aunque mantuvieran que el escribir poemas en si es acto político y todo poema implícitamente tal, no leyeron poemas sobre perales o cuervos o ranas o el amor sino los poemas que habían escogido leer eran indudablemente, poderosamente políticos. En mis observaciones de apertura había dicho que porque éramos criaturas sociales todo lo que hagamos es político; no votar cuando podamos en una elección es en sí acto político. A demás, dije, un acto, un poema es cargado o no con significado político por el contexto en el cual fue escrito. En el contexto de la degradación ambiental la poesía sobre la naturaleza se pudiera leer como implícitamente política. Eso dicho, si el poema sobre el peral fuera escrito cuando los perales fueran envenenados por pesticidas, o los cuervos cazados a cerca extinción, esos poemas pudieran tener brillo fuertemente político. Por lo tanto si Basho hubiera escrito bajo un régimen tirano que criminalizaba el derecho de expresión para mantener el statu quo, el chapoteo de su rana pudiera haber sido aunque implícitamente políticamente ruidoso. Todo es contexto cuando todo se ha dicho; todo lo que existe es relación. Tal es mi teoría de la relatividad. Pero todavía necesitamos una definición práctica de lo que es la poesía política y para eso propongo esta: “La poesía política es esa que habla en oposición o apoyo, en crítica o justificación de las instituciones y normas que nos gobiernan.” Resiento de tener que escribir poesía política; mucho preferiría escribir poemas de amor, poemas en alabanza de la vida, de la Tierra que la sostiene, poemas de asombro por lo que se percibe y por lo que se imagina. Por lo cual resiento de tener que escribir poesía política es porque me siento obligado a oponerme a las instituciones que nos gobiernan. Si esas instituciones fueran fundadas en y gobernaran con justicia, con compasión, con reverencia a la vida y a la Tierra que nos da nacer, sería yo libre para escribir sin impedimento en celebración y mi poesía “política” sería en alabanza de esas instituciones y con dificultad se distinguieran de mi celebración de la vida misma. Por supuesto que eso sería una Utopía y siendo los humanos que somos siempre hubiera cosas que criticar, o ignorar. Pero los Estados Unidos de América donde vivo y de cual soy ciudadano es mucho más cerca a una Distopía y en este contexto mi poesía (o mucha de ella porque también escribo mucha que es puramente celebratoria) tiene que ser abierta y fuertemente política en oposición a la injusticia, crueldad, locura que son las normas con las cuales se gobierna la nación (imperio). Mi poesía política es la poesía del amor violado. Entre las muchas violaciones de los derechos humanos que el gobierno estadounidense comete una que más me llega es su política hacia la migración, inhumana, cruel, demente. Las fronteras son de por si políticas y solamente tal, nada más. Los mapas mienten Borders are scratched across the hearts of men By strangers with a calm, judicial pen, And when the borders bleed we watch with dread The lines of ink across the map turn red. --Marya Mannes

Nací en frontera cargada en particular de política— la frontera entre los EE.UU. y México, Cd. Juárez, Chihuahua y El Paso, Tejas. Lo particular de esta frontera es que la tierra estadounidense al norte del Río Bravo, “la frontera,” fue robada por invasión por los EE.UU. Mucha de la población en esa Tierra es de descendencia y cultura mexicana — es tierra nuestra robada. A demás, la mayoría de nosotros somos de sangre mestiza, mezcla de sangre europea e indígena. Para nosotros, la parte nuestra indígena, las fronteras no existían como tales, la Tierra pertenecía a nadie, era de todos. Mi familia llegaron cuando la revolución mexicana de 1910 llegaba a su fin en 1920, mis padres apenas adolescentes. Así es que yo me crié bicultural, bilingüe entre y participando en dos distintas culturas. Mis padres siempre insistieron que conserváramos nuestra cultura mexicana y lengua castellana a la vez que aprendiéramos el inglés. No siempre fue fácil. La cultura estadounidense es poco tolerante de lo extranjero e insiste en que el inmigrante se asimile. En la escuela nos castigaban si hablábamos en español en la aula o el patio de recreo y aun muchos nos sentimos obligados a defender nuestros propios nombres. El prejuicio en la sociedad en general es grande. Muchos padres para proteger a sus hij@s de los efectos de este prejuicio les permitían hablar sólo inglés para que avanzaran económica y socialmente. El costo de asimilarse es grande.

Demasiado, es mucho el costo. Pera paro sobrevivir mucho se arriesga y mucho se pierde. Se emigra raras veces por gusto y casi siempre por necesidad. Históricamente la mayor parte de nuestra gente que emigra a los EE.UU. es gente pobre, más que nada campesinos que vienen a trabajar por muy bajos sueldos, largas y duras horas, bajo pésimas condiciones, muchos analfabetos o con poca escuela, muchos hablando lenguas indígenas. Vienen indocumentados y muchas veces traen sus familia, hij@s de muy tierna edad, infantes muchos. Es@s chicuel@s todavía indocumentados han crecido en jóvenes en todo estadounidenses menos en ciudadanía, muchos hablando y escribiendo solamente en inglés, muchísimos estudiantes en colegios y universidades. Y ahora el Presidente de los EE.UU. Pres. Trump (llamado entre nosotros con el no muy afectuoso apodo Pres. Trompudo) racista y fascista, ignorante, arrogante y descorazonado hasta las cachas intenta, con el apoyo de su índole, expulsarlos a sus países natales, países extraños para ell@s, países no suyos — México, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua y tantos más. Se les han llamado “Soñadores” apodo que origina en un plan del presidente anterior Pres. Obama para protegerl@s. Nuestros soñadores El país que echa fuera por falta de documentos a sus soñadores se hiere a si mismo. ¿Que otra tierra conocen? ¿Que vacío dejarían en la consciencia, en el corazón del pueblo? Es arrancarle las balanzas a la justicia, apagarle el antorcha a la libertad. Sería como si el águila con su propio pico y sus garras se rasgara su propio corazón ya envenenado por la crueldad. De fronteras y muros los sueños y la necesidad saben los mismo que las mariposas, las aves, el olor de las flores. Si no protegemos a nuestros soñadores perdemos nuestras almas y sueños. Con la ascendencia del Pres. Trompudo se ha demonizado el emigrante. El presidente les ha llamado violadores, asesinos, ladrones, especialmente a los emigrantes mexicanos, centro-americanos, latino-americanos (y además terroristas a los emigrantes musulmanes.) El fascismo, el racismo, el nacionalismo y el odio son patentes y se han normalizado en la discusión política estadounidense. Pero lo tenemos que decir claro -- Decirlo Claro Dicen los bobos que venimos de mendigos estómagos vacíos, vacías las manos para quitarles lo que ya sus propios canallas y bribones les robaron. Sí, venimos con hambre huyendo la violencia a donde la riqueza del impero se concentra pero con las manos llenas de nuestras artesanías y labores, corazones llenos de bailes y canciones, con nuestra cocina rica en sabores. Le traemos alma a una cultura desalmada; traemos el arco iris y prefieren el gris de sus temores. Se empeñan en construir muros si lo que se necesita es puentes. La frontera se ha militarizado y se ha hecho un frente de batalla. Y el Tompudo se empeña un construir una gran muralla por toda la frontera entre los EE.UU. y México a un costo aproximado de construir de 70 billones de dólares y de mantener a 21.6 billones de dólares. Y neciamente insiste que la pagará México. Pero no se le puede poner precio al costo del sufrimiento que ha causado, que causa esta política. Los emigrantes son aprendidos y encarcelados, las madres, los padres separados de sus hijit@s, muchos de ellos infantes, l@s niñ@s metidos en cárceles separadas, desparramados, enviados lejos. Y aunque las cortes han declarado estos hechos ilegales y exigido que se reúnan las familias, muchas todavía no se han reunido y niñ@s se han perdido. La crueldad, el sufrimiento hiere la imaginación. Es tan amable la luna La luna llena se cuela por entre las rejas de la cárcel de niños para recoger sus sollozos en su delantal de luz y llevárselos a sus padres en cárcel de adultos y traerles lamentos y bendiciones de sus madres, sus padres a los niños. Es tan amable la luna que no niega su luz ni a los malvados traficantes de angustia. Es tan amable la luna Y ¿que graves exigencias motivan a estos padres, madres a arriesgar tanto por emigrar a los EE.UU.? Vienen a donde se concentra la riqueza del imperio huyendo de la pobreza y la violencia de sus países causados por la política estadounidense: tratados de “libre comercio” que han sido desastrosos para la economía de México, la cínica “guerra contra las drogas” que ha traído violencia atroz a México, los Acuerdos de Mérida que han militarizado el gobierno de México y lo ha hecho aun más violento. Pero no es solamente México sino es así en toda América Central y en partes de Sud América. Se cultivan y se apoyan gobiernos abusivos por el poderoso EE. UU. que para el bien de los ricos mantienen a sus pueblos en pobreza y represión violenta, vendiendo sus tierras y recursos naturales a empresas extranjeras estadounidenses e globales. Y l@s que resisten y defienden la Tierra (gran parte indígenas y mujeres) son torturados y muertos. Un caso representante de muchos, muchos otros por todas las Américas es el de Berta Cáceres de Honduras: Por medio milenio y más a Berta Cáceres y a todos los mártires de las Américas muertos defendiendo la tierra

Nombrémoslo por lo que esencialmente es: la economía de imperio, el capitalismo, y su política, un sistema económico que se basa en dos cosas: el tratar a la Tierra solamente como deposito de materia prima para explotarse y la esclavitud de mano de obra para convertir esa materia prima en productos consumibles a abajo costo para vender a gran ganancia para el bien de los pocos. Fue nada más que esto lo que impulsó la conquista de las “Américas.” (De la religión que hacía mucho se había hecho instrumento del estado y justificaba la esclavitud y hasta el genocidio no diré nada, ni de la oposición dentro ella que nos llega ahora como la teología de la liberación.) Por ser los EE.UU. el más grande imperio actual y su presidente un Calígula moderno, es fácil hacerlo el único villano, pero esto pasa casi por el mundo entero. El capitalismo desenfrenado lleva al fascismo y esto lo vemos por a través del mundo actual. Las guerras y tiranías casi todas a causa del capitalismo desplazan una gran cantidad de gente huyendo del la pobreza y la violencia para sobrevivir. La migración es unos de los “problemas” más grandes del día no obstante que la humanidad siempre ha migrado desde su origen en África hace tres cientos mil a dos cientos mil años. Migración ¿Qué sabe la mariposa de fronteras? ¿Qué sabe de banderas? Cruza todo un continente, el movimiento su herencia. Así es con nosotros, nuestra historia migración de años, de siglos, de milenios antes de que historia hubiera y que formáramos mitos en el cerebro. Nuestros pasos hechos de sangre, de lágrimas, de risas, de sudor marcan nuestra eterna búsqueda de hogar señalado por el Dios, o el águila comiéndose una culebra o quien sabe que señas arbitrarias. Pero son inseguras nuestras moradas -- hogar es la Tierra redonda y sin costura; la circundamos y si patria veneramos es pretensión, es mito, es mentira -- buscamos abrigo, alimento, libertad, la vida. Abajo con fronteras, abajo con banderas que si justicia y paz hubiera no tuviéramos que vagar tanto por la Tierra. Nací, vivo en y soy ciudadano de los Estados Unidos de América pero más que nada me siento ciudadano del mundo. Mi lealtad es a la humanidad a cual pertenezco y a la Tierra que nos dio nacer y nos sostiene. Mi ciudadanía estadounidense y terrestre me obliga a ver críticamente a mi país, al mundo, a la humanidad. Pero si he pintado a mi país en matices sombríos no es completamente fiel el retrato. Muchos, muchos estadounidenses no son racista, ni tóxicamente nacionalistas, ni injustos, ni crueles, ni capitalistas. Y son muchos los problemas del imperio y me he enfocado sólo en la migración. Es muy grande la resistencia contra las fuerzas del fascismo, es grande la compasión y el deseo por la justicia. Muchas ciudades y aun estados se han declarado ciudades, estados “De asilo” para proteger a los inmigrantes indocumentados negándose a colaborar con la policía federal en la persecución de los inmigrantes. Diariamente hay manifestaciones a las puertas de las cárceles, la frontera, los aeropuertos, los edificios de gobierno, las calles en apoyo de los inmigrantes. Hay una gran lucha entre las fuerzas del fascismo que controlan el gobierno y las fuerzas demócratas. Estamos en crisis y son tiempos temerosos. En cuanto a mí como viejo y poeta Te Digo Te digo que estoy cansado de no poder darle la espalda a la injusticia y crueldad del mundo. Quisiera en vez contarte lo que el sauco y la secoya, la piedra en el arroyo hecha lisa por el toque suave o brusco del agua me dicen. Quisiera decirte los cuentos del lagartijo y la mariposa, cantarte las canciones calladas de la madreselva y el romero. Quisiera escribir versos de amor a la Tierra, a la vida, a ti. Pero no puedo darle la espalda a la injusticia y crueldad del mundo que causa tanta pena y sufrir en la Tierra. Mis versos de furia y protesta son también poemas de amor, de un amor traicionado y herido. © Rafael Jesús González 2018. --o0o-- “Political poetry is that which addresses, in opposition or support, criticism or justification, the institutions and norms that govern us.” |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed