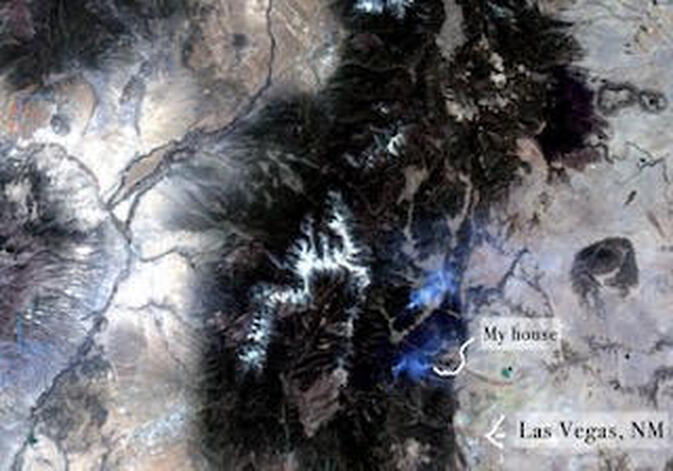

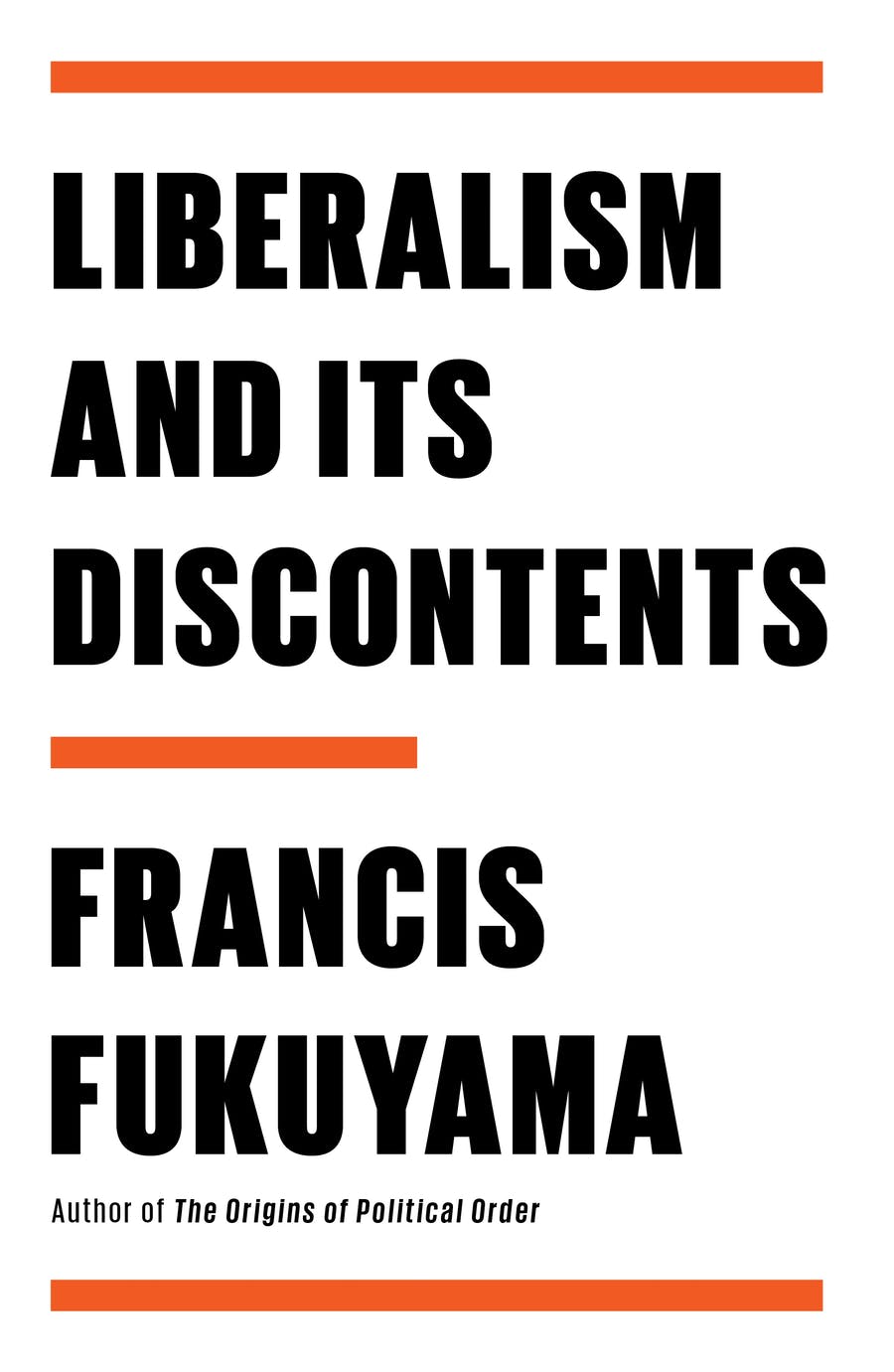

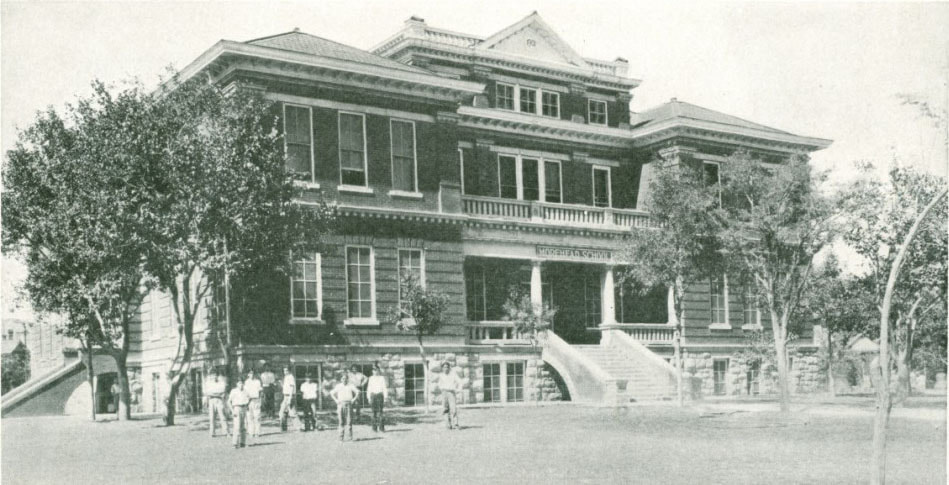

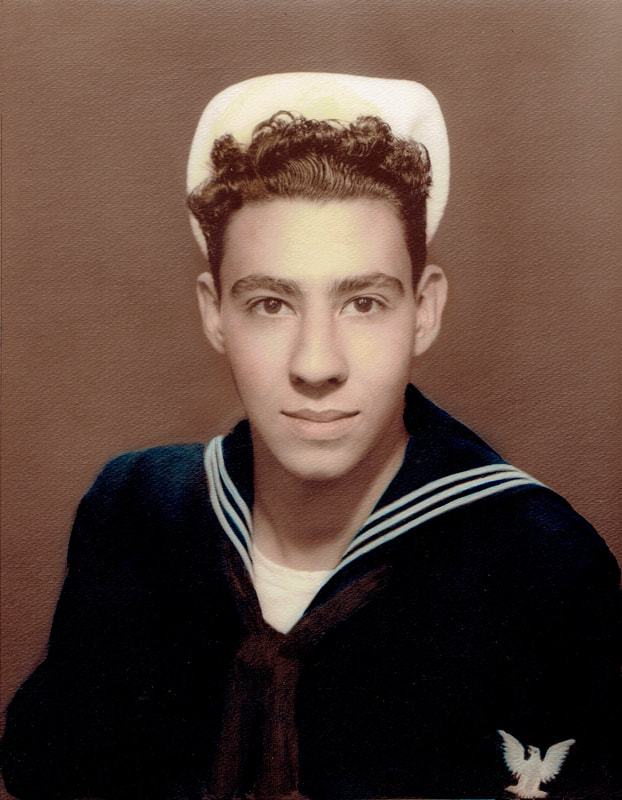

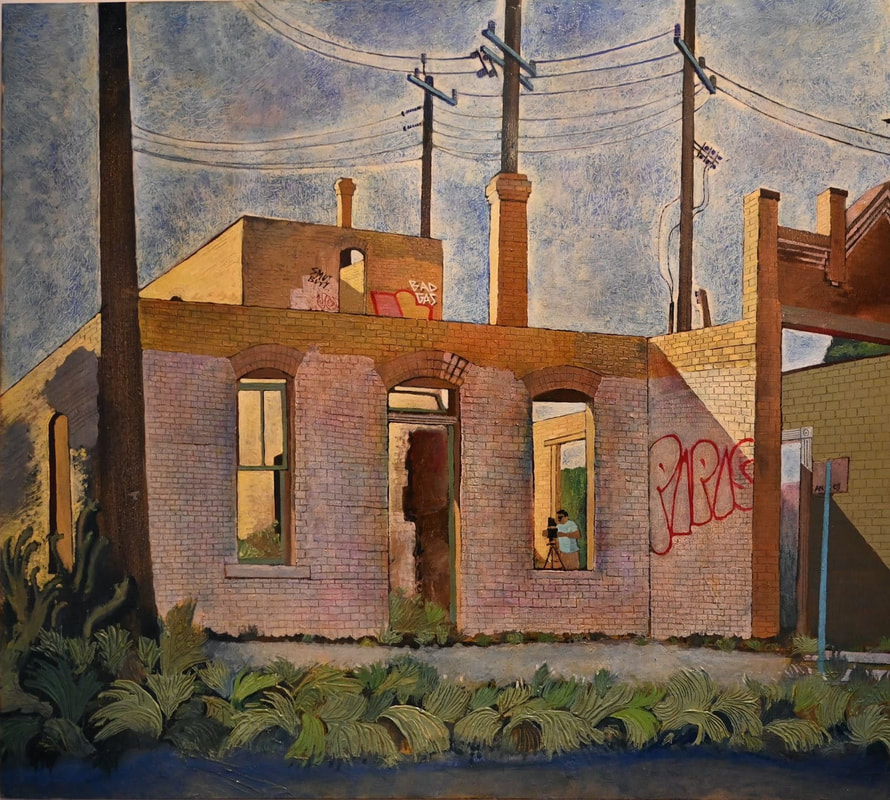

The Red Beastby Carmen Baca A careless human act gave birth to the monster. Like any good creators of a living, breathing thing, the people responsible for the debacle came up with a procedure backed by science for success. But sometimes plans go awry; any monster from literature, the arts, or folklore and legends is proof. Plans made far in advance were now outdated, weather predictions ignored. Obeying the command to proceed without weighing the potential outcomes, the crew lost control of the creature before they realized. It flickered to life and licked the dry grass around it, lapping up sustenance to appease its hunger. It grew, spreading its extremities to gather more water-starved vegetation into its maw. The brown, parched weeds whetted the beast’s appetite, and it turned on its creators. The nameless group gave the outcry as they escaped, the alarm echoing from one hill to the next. The flora recoiled and the fauna fled in terrified retreat. The red beast grew and spread and devoured all in its path. It had no plan. Mindless consumption drove it forth. It created new fronts and doubled in size in a matter of minutes. It reached for more food to fuel its advance.  “A few days before we evacuated on April 22.” Photo and caption by Carmen Baca. “A few days before we evacuated on April 22.” Photo and caption by Carmen Baca. The winds blew it farther, in all directions, often shifting from one to the other, morning to afternoon and far into the night. As hours turned into days, it covered more ground. Alarm amongst us rural residents in its way grew as our vecinos, people closer to it, watched it draw near. Surely, the crews fighting it would stop it soon. But the beast created its own weather. Powerful, relentless winds pushed it over more arid earth, growing in acreage, sometimes by the hundreds and later, by the thousands in a matter of hours, as reported by those who sought to bring it under control. Wrapping itself around living organisms and taking the life from them in an instant, the menace spread across the landscape, covering all in black and red. Days later it doubled in size. The 50-70 mile an hour winds sent it forth with ferocity. It created Pyrocumulus clouds which rose over 30 thousand feet, obscuring the blue and roaring over the land with renewed power. TV news reporters stood with tall plumes behind them, signaling the route of the red beast. Their cameramen’s lenses showed us the destruction from several locations, different angles, and points of view from authorities, from the fighters in the battle zone, and from people potentially in its path if it proved unstoppable, waiting for instructions and preparing just in case. Our hearts grew heavy. The beast occupied all our thoughts and so many of our nightmares. It fed voraciously on the forestlands beneath and those surrounding Hermits Peak. Those in command of the fire fight announced the coming days would be catastrophic; the area consumed would grow exponentially with the propulsion of the winds. Those fighting from the skies were forced to abandon their pursuit while those battling on the ground retreated more than they advanced. The intensity of the monster’s hot, fiery breath would have incinerated them otherwise. The morning and evening reports about the swift growth of the red terror struck those of us closest to the path of the enemy. We learned how to navigate several fire maps online, our fear weighing us down and our anxiety burning in our guts as we saw the burned area growing larger by the hour. When it reached the community of Pendaries Village, it swooped down over the pine-covered mountains on either side, enveloping them in its fiery, destructive embrace. The plumes rose in billows of black; then they turned white, and finally brown as they covered the sky. The velocity of the winds gave breath to the fire-head on that day. As though a giant blew out a candle, the flames exploded before they whooshed between the mountains on both sides. Out of control, the inferno fed on the ancient pines and spruces, the fir, conifer, and the wild oak. All disappeared into towers of flames, entire mountain tops of trees glowing red, inspiring terror in all who saw them. Those woodland creatures which could escape fled. The sun glared in a fiery orange ball behind the yellow-brown haze, day after day, enveloping everything in a smothering, poisonous fog. Ash fell and embers glowed. Day turned to night for those closest to the danger. And the now enormous enemy continued to fill its belly with everything in its path, devouring one house here and leaving the neighbor’s over there untouched. The monster didn’t choose its food; its wind-driven route determined which structure it ate and how many of them fed its hunger. The people from the hamlets, the villages, and the rural communities obeyed the orders to evacuate: San Ignacio, Las Dispensas, and Las Tusas first, followed by Rociada and Gascón, our closest vecinos in Tierra Monte several miles away, and us. Only a handful of us remained in Cañoncito de las Manuelitas. We looked the red beast right in the face that day, and we knew we had misjudged. The dense, smothering smoke swooped down over us, forcing us to wear our Covid masks again. As dusk turned into midnight black, we fled in a caravan, surprised to see other residents down the road a few miles had also waited until they no longer could. We joined vehicles merging onto the highway, our line of headlights snaking down Nine Mile Hill to the nearest town, Las Vegas. Those beacons just ahead and closest behind guided us as we crept down the road. Even the red crowns of the tallest trees disappeared into the black of April 22, 2022. A week later, the neighborhoods on the far west side of Las Vegas received the alert to evacuate. The beast had followed us, about four thousand evacuees in total, and now threatened close to thirteen thousand more New Mexican residents. Two colleges in the vicinity evacuated, and the town shuddered in fear that night. Days later, the erratic winds blew the gargantuan southwest toward San Geronimo and northeast toward the communities of Sapello and La Tewa. After another few days, more communities fled. Social media flooded with all manner of posts from photos to videos of flames people shot from their front yards. Glimpses of the red beast from many locations made the national newspapers. As the now enormous monster terrorized so many communities, TV news reporters interviewed those who lost everything, and from their helicopters, cameras panned out to show the world how our landscape went from pastoral meadows and verdant mountain forestlands to miles of blackened, limbless trees standing like tall arrows pointed at the skies, the ground beneath a mix of gray ash and black soot. Homes, barns, and outbuildings which had been in families for decades turned into piles of rubble, many topped with the bent and curled-up tin which had been their roofs. The red beast played a game of Russian roulette with the land, ingesting one section of forest and leaving another over the next hill alive, devouring an entire rural community while bypassing the one beside it. Like Death, the beast was indiscriminate. It felt no empathy for those whose lives it afflicted, feeding itself with their priceless treasures, heirlooms, and family inheritances. It bore no sympathy for the flora or the fauna it consumed. Close to 80 days passed as the monster fed itself, terrorizing the people and the animals in its path. In early June, with over 341 thousand acres of destruction in its wake, it slowed in consumption. Some days it held in containment; other days it grew by several hundred acres. We hoped the end of the nightmare was close. But we also knew it could revive in any location where hot spots remained, those smoldering trunks or burning utility poles, dense material not easily extinguished. The beast, even in pieces, could threaten us once more. It wasn’t likely to return over the already destroyed areas since it sought fuel to reanimate. Our forestlands were burned or badly singed, but our Cañoncito, the valley between the mountains, remained mostly intact the night the fire head swooped over us and left our vecinos in Tierra Monte with nothing. A shift of the winds could bring the flames back upon us. We prayed for the beast to become more subdued by the day until we could draw deep breaths and let the anxiety fall off our bodies. We longed for blue skies and days without rising plumes. For the spirits of our dead, our Antepasados, the devastation proved too much. They, like their descendants, us Norteños, had maintained their faith that the army with its pumper trucks and bulldozers, hot shot crews and smoke jumpers on the ground, and the air tankers, scoopers, and choppers in the air would kill the beast and end its terror. Our dead heard our heartbreak over our inheritance—the ancestral lands and the cherished adobe houses they left us. They heard our combined prayers and succumbed to our despair. Our forefathers cried in the heavens, and the rains fell upon the red beast which had wreaked terror in the four directions and became the largest disaster in the Land of Enchantment. The scientific theory meteorologists offered was that the monsoons came early in June of 2022. We Norteños know the truth. We, the victims of the ravenous monster, touched the hearts of our forefathers with our prayers and our tears of helplessness. We had done nothing to bring the beast down upon us. Nothing. The same people who gave life to the monstrosity known forever more as the Hermits Peak Calf Canyon Fire now warned us we needed to steel ourselves for the next disaster: floods from the burn scars left in the wake of the beast. As though trying one last weapon to assault us, the beast did as predicted. The monsoons fell gentle and steady at first, not in downpours or cloudbursts. The Ancianos in the heavens cried with a quiet sympathy for us, their progeny, and our plight. The tears brought refreshment to the parched earth with a gentle touch. Then the rains turned more fierce and the almost daily flooding ensued, and we knew our Antepasados’ hearts had broken. Their sorrows combined with ours as we watched what had survived the fires now succumbed to the destruction from the flood waters. The red beast had been vanquished after 144 days, but it took out its revenge long after it had breathed its first breath.  “This is the forest where my stories take place. The green growth is something we’ve never had before. The ground is gray from the ash, soot, and flood water debris.” Photo and caption by Carmen Baca.  Carmen Baca taught high school and college for thirty-six years before retiring in 2014. Her 2017 debut novel, El Hermano was a New Mexico-Arizona Book Awards Finalist in 2018. Her third book, Cuentos del Cañón, received first place for short story fiction anthology from the same program in 2020. Her latest novel, Bella Collector of Cuentos, was published by Somos en escrito Literary Foundation Press in November 2022 (order a copy here). She has published five books and over fifty short works in online literary magazines and anthologies. She and her husband live a quiet country life in the mountains near Las Vegas, New Mexico, caring for their animals and any stray cat that happens to come by.

2 Comments