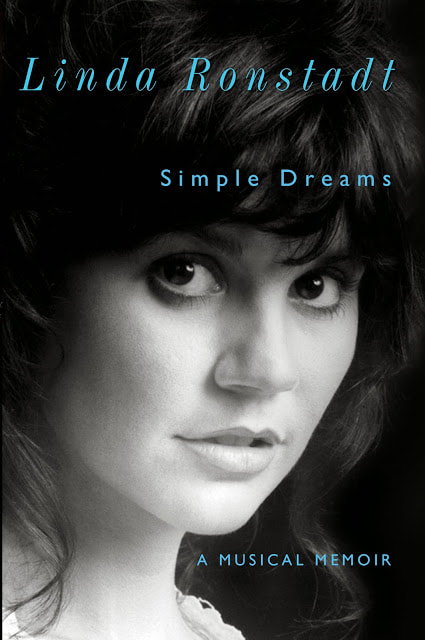

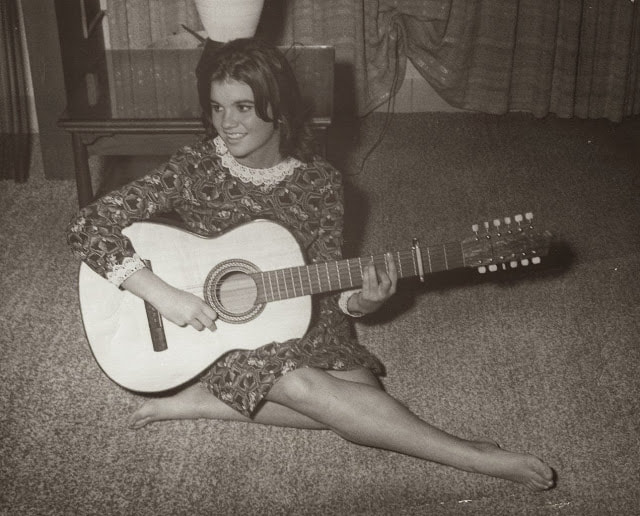

Review of Linda Ronstadt, Simple Dreams, A Musical Memoir, also in Spanish: Suenos Sencillos, Memorias Musicalesby Michael A. Olivas It is too early to mourn the passing of Linda Ronstadt, but as the popular press has shown, it is not too early to note the passing of her voice and singing career, struck mute by Parkinson’s. In a very oblique fashion and with understated tones, she surfaced her health situation in an AARP publication in August 2013. However prematurely, I have been in mourning, all the more since I read her self-written autobiography, Simple Dreams, A Musical Memoir and its Spanish counterpart, Sueños Sencillos, Memorias Musicales. If there were any woman who epitomized 1960s rock and roll, it was she—maybe Janis Joplin, who flamed out too early to tell. She met Joplin when they were both starting out and trying to get paying gigs at L.A.’s The Troubadour, home to so many classic singers and groups. She remembers her briefly, with Joplin telling her that she was there to try out a new dress, and that she felt pretty. Ronstadt’s own nomination for the Queen of Rock and Roll is Chrissie Hynde; she calls the Pretenders’ member the “first fully realized female rocker,” modestly giving her “my crown, however tenuously it hovered above” her own head. She is nothing if not modest, this female Zelig, who knew or sang with Frank Zappa, the Doors, Kris Kristofferson, Jerry Jeff Walker, Neil Young, the Eagles (her back up band), Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris, Lowell George, Jackson Browne, Ricky Skaggs, Roy Orbison, Aaron Neville, and many dozens more: a modern rock era who’s who. She knew Pamela Des Barres and Leslie Van Houten, surely an odd bookend of acquaintances. I first learned of her Parkinson’s from a New Yorker article that came out soon after the AARP story, and which says better than I can what her accomplishments across genres were. And the NY Times followed closely on its heels with its own story, and she has now appeared on television and NPR and elsewhere—dutifully flogging the book and wistfully recalling her past accomplishments with the prodding of doting interviewers. But I will always love her voice most from the 1977 album “Simple Dreams,” and the sublime mariachi album, “Canciones de Mi Padre.” I saw her twice, once with the Stone Poneys at the Albuquerque Tingley Coliseum, on the NM State Fairgrounds, when the band played a double bill with Three Dog Night. I fell hard for her, and her voice, and when I heard she had dated Jerry Brown, I not only voted for him in the presidential primary years later, but contemplated leaving the seminary for her. (He spent one year in the seminary, although he has gotten plenty of mileage out of the experience.) She notes that they remained good friends, in part because they had no musical interest overlap together. I then saw her and Kevin Kline in a glorious “Pirates of Penzance” in Central Park, when she was in her operatic phase. I would argue that no one who was so successful in rock and roll has been so versatile across types of music. She writes of her light operetta interests, her one unsuccessful foray (an imperfect attempt at “La Boheme”), her countrified phase (with Dolly and Emmilou), her Nelson Riddle orchestral phase, where the famous arranger dies in the final stages of their collaboration, and what became her final works, a Christmas album and more classics and rancheras. Then, in 2009, the music died. In the book, she essentially takes readers through the almost-40 years of her recording career, letting us know why she had such a wide-ranging repertoire—all songs and genres she heard in her childhood Tucson home, where her father and other relatives were amateur singers, mostly of Mexican and Spanish songs, which she absorbed until they burst from her with her 1987 Canciones. Starting out with a local group, the Stone Poneys, she hit the big time with “Different Drum,” a song she had to fight to get onto the group’s second album, where it went to No. 1. Soon after, she left to find her own way, with the then-unknown Eagles as her sometimes-backup band, and then her true discography and travelogue begin. She matter-of-factly reports the problems she had, with lecherous men, many other men she either dated or befriended, and who protected her. In my reading, these are the most interesting and informative parts of her considerable backstory, leading to the many artistic decisions she made about finding her voice(s) and the musical paths she wanted to carve out. It is quite fascinating to learn how she made her choices, how hard it was for a woman of her stature to get the institutional support to pick her own music, and how mind-numbing the time between concerts on the road must be, especially for a single woman. And she includes great family and professional pictures into the text. I was impressed that she wrote this herself, and my only regret (other than never meeting her and her not having been selected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame) is that no strong continuity editor worked over her text. In several places, people just sort of jump in and out of left field—the two I jotted down were Maria Muldaur ("Midnight at the Oasis")—who appears as the mysterious “Maria” early on, admired by her and Janis Joplin; and her two children, completely dropped in, who make cameo appearances without any introductions at all in the last few pages. I only figured that Maria was Maria D’Amato Muldaur because I knew (somehow) that she had married Geoff Muldaur and the two of them had played together in Jim Kweskin’s Jug Band, mentioned but not explained.  Linda in her favorite striped dress Linda in her favorite striped dress There are several such ellipses, but it is a very good read, and you can surely dance to it, in both the English or Spanish renditions. And almost no one has written for English-speaking audiences about the many Mexican and Mexican-American music personalities and recording business. Parkinson’s disease has taken several of my close friends, and it is a cruel and debilitating disease. I hope her time left is fruitful and peaceful. I have been playing non-stop her “Greatest Hits” albums, and marvel again at just how beautiful and versatile her voice was. I hope that she knows just how many people have appreciated her accomplishments and have adored her. A high school friend who knew of my early stages of grief put me on to the Diane Sawyer interview with her, which I had not seen. (It is on YouTube.) She is, as always, very matter of fact, and I love that when she is asked about whether or not she is mad (about her disease), she misunderstands, and says, "sure, about immigration." Gawd, I just love this woman, this great beautiful Mexican woman. There have been and soon will be more reports on her fascinating and iconic life, including books by others (such as Graham Nash), that discuss her extensively. Still, listening to her on almost any of her three-dozen-plus albums is reward enough. She sang at her great fellow-Tucson artist Lalo Guerrero’s funeral. When she passes, which I hope will be in many years, can you imagine the tremendous lineup of singers at her graveside?  Michael A. Olivas is the William B. Bates Distinguished Chair in Law at the University of Houston Law Center and Director of the Institute for Higher Education Law and Governance at UH. He has recently published No Undocumented Child Left Behind (NYU Press), In Defense of My People: Alonso S. Perales and the Development of Mexican-American Public Intellectuals, (Arte Público Press), and Suing Alma Mater (Johns Hopkins University Press) earlier this year. With this review, he reveals a remarkable knowledge of rock and roll and a shared crush on Linda. Simple Dreams is published by Simon and Schuster.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed