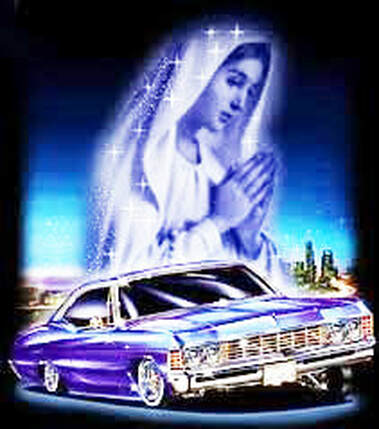

Chicano Confidential The Night La Virgen Crashed Corky’s Party for César By Sonny Boy Arias Federico Peña, Denver’s first Chicano Mayor once hosted a reception for César Chavez at his home. In attendance were a Chicano congressman, Chicano State Senator, Chicana Assemblywomen, a Chicano member of the State Board of Education, several Chicano community activists like the directors of Brother’s Redevelopment Corporation and the Community Action Program and a half dozen Chicano professors (including myself), now how Chicano is that? I never felt so Chicano in my life. We used to meet weekly at El Metro, a local bar located in the barrio on Santa Fe Boulevard downtown Denver across the street from the Metropolitan State College of Denver to strategize who was going to run for which political office next. We saw this as our official meeting place, the “space for change” we called it. We used to test-out community planning ideas with influential Denver politicos prior to going public; it’s the place we planned to bring César when he came to town but were only able to get him to Federico Peña’s house located in an up-scale part of Denver known as Cherry Creek not far from the Tattered Book Store and Lyle Alzado’s Bar (former professional football player for the Denver Broncos who was drafted to the Oakland Raiders). My wife, Patricia, and Federico’s first wife Ellen were jogging buddies so I heard first-hand that she encouraged him to invite just a handful of people for the reception, but it turned out to be more of a Chicano-style pachanga. Prior to César’s arrival I estimated some two hundred and fifty people in-and-around Peña’s house, and once the students arrived it swelled easily to over four hundred. Important to note is that given a number of recent clashes with the police it was obvious that there were no police in sight; another of Mayor Peña’s strategies as his message to the Denver Police Department and to the dismay of the Chief of Police (an outspoken officer who always spoke in defense of his junior officers for having shot and killed a number of Chicanitos) was, “We can take care of our own!” I noticed a beautifully remodeled 1960ish low-rider Chevy with a picturesque spray painting of César Chávez on the trunk reflecting off a well-placed black-light projecting a purple ray of light from the dashboard approaching the house at a Chicano speed of one mile per hour; it was travelling low-and-slow, not just because the crowd was thick but to also give people time to place their hands on the spray-paintings of César on the trunk and/or La Virgen de Guadalupe (The Virgin Mary) on the hood. People rubbed the images as if they were touching the shroud of Jesus. Both were dimly lit yet quite visible giving the low-rider a heavenly luminescent look amidst cold fog-breathing onlookers with a Rocky Mountain background and La Luna (The Moon) watching over. At least a couple hundred students walked behind the vehicle–it was like a cross between a spiritual and social movement all at once–Chicano style to be sure. The young students from the Escuela Tlatelolco (who were not invited to the reception but defined Mayor Peña’s house as a newly found part of their community) led the chant “Que viva César Chávez!” and the crowd would respond with “Que viva!” Prior to the long walk from Five Points (a place where five main interconnecting streets converged stretching out from each of Denver’s barrios), César had met with the students: his message to them was that there were two types of effective social change: slow and fast and that it is highly important to first lay the foundation for any change to occur and they must always take action on both depending on the signs (albeit, needs) of the times and that public social protest was the best way to bring attention to social problems; many Chicano students reported their lives’ were forever changed by this encounter. Upon César’s arrival, Rodolfo Corky Gonzalez immediately stepped out of the low-rider wearing a black silk jet fighter pilot-like coat with bright-red heavily threaded letters with his prize winning name on the back “Corky the Champ!” along with an intense look on his face just as he looked before entering the ring for a boxing match as he had done so many times before. César followed, wearing his prize winning smile. As they made their way out of the car and up to the front-porch the stark contrast between César and Corky was peculiar yet positive, César was never so Chicano and for this event Corky was not the main event, not even in his own town as the real Champ had arrived. Realizing he was in the presence of grandeur, Corky took his place directly behind César with his arms extended and at the same time holding onto César’s shoulders in precisely the same manner in which a prize fighter enters the ring. As the chants grew to almost deafening pitches, “Que viva César Chávez!” – there appeared an image of La Virgen de Guadalupe on the large bay window of the living room for all to see. It was clear-as-day, floating as if suspended about four feet off the ground. Neither César nor Corky knew what to think or say. As it turns out the image was actually a reflection from the dimly lit image of La Virgen reflecting off the low-rider and accentuated by the light of the silvery moon –the bay window acted like a bright reflection off a giant movie screen. La Luna shown beautifully and bright that night as if she were looking over us and providing the light for taking back the night in this Rocky Mountain town with a cowboy past and a Chicano future, with so much political turmoil during those tumultuous times. Chicanos and Chicanas were ripe for this moment, simply stated, “It just had to be!” With several hundred people standing in the yard and because the low-rider was riding low-and-slow most people could not see the image of La Virgen reflecting off the car but word spread quickly so they were immediately convinced the Virgin Mary had made an appearance, after-all seeing is believing! The large and colorful image of La Virgen stunned the crowd. I cannot stress the impact it had momentarily on us all. The fact that the bay window was also reflecting the shadows of the people standing nearest the window as they moved about brought more life to the image. In just a matter of seconds following her appearance, the crowd let out a subtle moan as dozens of people repeated “Oh my God! Oh my God!” All at once people began making the Sign-of-the-Cross the way Catholics do and for many they kept making it over-and-over again like the way Latino professional baseball players do when they go up to bat. People produced Rosaries from their pockets and began praying the Lord’s Prayer; you could hear them praying in both Spanish and in English yet in unison as if it were orchestrated from heaven above: Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name; thy kingdom come; thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen. One elderly woman near the bay window cried out that a bed of “velvety-red roses” had also appeared beneath the window just like the roses Juan Diego, a Nahua peasant, had shared in a cloak upon her apparition back in 1531. When she said this hundreds of heads turned back to the window, some with skepticism but sure enough there was a beautiful bed of “velvety-red roses.” It was in fact Mayor Peña’s rose bed; even he was astounded, however, at both the appearance and beauty of the roses as he had just trimmed each rose bush down to three conjoining stems as he was taught by his grandfather; even his wife Ellen commented that she had just taken the garbage out including all the trimmings from the rose bushes leaving no trace of roses for the season. It wasn’t hard to see the wonder in everyone’s faces. Over-and-over again for a good ten minutes people repeated the Lord’s Prayer. I noticed that none of the children from the Escuela Tlatelolco joined in on the recitation as they were taught to question authority through a critical lens and they were not enchanted with the Catholic Church. Nearly all of the children from the escuela were trilingual speaking, Spanish, English and Nahuatl, a language indigenous to regions in and around the Aztec Empire and used by Chicanos so as not to be understood by others. Several dozen prayers had gone by when it started to feel a little too Catholic; even with the image on the bay window, things started to feel odd, especially to Chicanos who had not had positive experiences with priests and/or nuns in Catholic school. Tacitly, it goes without saying, “No one dared to stop the people from praying!” In all his wisdom, however, derived from his experiences as a prize fighter who often during bouts would start praying at a point when he thought he didn’t have the strength to win until he saw a vision of La Virgen, Corky decided to include a good dose of ascetic mysticism: he spoke loudly into a portable microphone system he always seemed to have by his side and broke the cadence of the prayers: “People! People! My brothers and my sisters, as you are a witness today, La Virgen de Guadalupe is with us in support of our causa; she is ‘Guadalupe’ named for the one who can ‘crush the serpent’ [a reference to the Aztec serpent-god Quetzalcoatl]. With her support we can achieve anything; it is good to have a friend in heaven! Because we are Chicanos, we are Quetzalcoatl, so together with Our Lady we will overcome injustices in our community and any conflicts in our hearts. Que viva La Virgen y que viva César Chávez!” And the crowd responded with, “Que viva!” César’s smile was bigger than ever. As they stood on the porch only three feet off the ground much like César does while standing on Andy Boy wooden crates in the fields when speaking to farmworkers, Corky held the portable microphone up for César (in the same way Luis Valdez used to hold it for César) and proceeded to reach into the right-side back pocket of his khaki pants and retrieve a well-worn paperback copy of Herbert Marcuse’s One Dimensional Man (1964), the same one given him by Marcuse when he visited with him at the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute in La Jolla, Califas. While pointing to the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe on the bay window quoted Marcuse by stating loud enough for everyone present to hear: “It is only for the sake of those without hope that hope is given to us!” The response from the crowd was dozens of chants: “Que viva César Chávez! Que viva César Chávez! Que viva César Chávez! Que viva César Chávez! Que viva César Chávez! Que viva César Chávez!” As the chants grew deafening, the children of the Escuela Tlatelolco lined up along the porch, two dozen of them dressed in china poblana dresses (a traditional style worn by Mexican women) and then as if apparitions themselves, two Denver police officers showed up to report a disturbing the peace complaint and the children of the escuela began chanting as if on cue: “Fuck the pigs get them out of our community! Fuck the pigs get them out of our community! Fuck the pigs get them out of our community!” As the White and Mexican American police officers approached Mayor Peña, he looked at Corky and Corky looked at César andCésar glanced over to the beautiful brown children and they were giving the police officers mal ojo (evil eye) while at the same time continuing to chant “Fuck the pigs get them out of our community!”I heard Corky, say to the children “Okay, great; ten more times!” As the children were winding down the Mayor excused the police officers and the crowd went wild. [Following the event, I heard through my wife that the Mayor told the police officers to stay away from his home and that “We are Chicanos; we can police our own community.”] César held up the youngest of the Chicanitas who in turn led the crowd with a traditional Chicano hand clap; as everyone clapped César kissed each and every one of “Quixote’s soldiers” on the cheek and everyone broke out into a grand version of De Colores, a traditional Mexican song which became an anthem of the farmworker movement. It didn’t matter from which of the five Denver barrios you were from, I could sense that everyone in attendance felt an affinity that evening as the Chicano community knew who they were and where they stood; they had shared meanings, common values and beliefs and they had La Virgen and César Chávez in their midst. The only thing missing was the Chicano National Anthem “Low-Rider” or is it “Sabor a Mi?” Anyway the car clubs were all at peace that night. After only an hour-and-a-half, César was suddenly whisked away as rumor had it that there had been an attempt on his life in the dining room. In reality what had happened was that César was in a rather intense conversation with Mayor Peña’s wife Ellen surrounding issues of health and nutrition (after all she was in training for long distance running for the Olympics) when a woman weighing over four-hundred pounds fell from her bamboo bar stool (the chair appeared to have exploded right under her wide bottom) and toppled over onto the Mayor, who was rather small in stature and squirmed like a smashed bug beneath her. I know as I was sitting next to him; it took several seconds for anyone to take action. We were so aghast with what had just happened we simply could not believe our eyes and besides La Virgen de Guadalupe was still on the bay window. It was a difficult cognitive shift from hearing the bamboo all at once crackling as well as the sound of the woman hitting the floor, just as it was a surprise hearing the Mayor moan like someone who had just been knocked out in a prize fight. Psychologically all that registered in our minds for the several seconds that ensued were the sounds of the sudden commotion. To say the least, we were stunned, rendered speechless, paralyzed with new found emotions, how else can I put it? All we could see was the Mayor’s preppy glasses, a few strands of his cold-black hair and his right hand pounding on the floor as if tapping out from a professional wrestling match. In a knee-jerk reaction, Corky went into a prize fighting stance as he had been trained to do for so many years and a few Brown Berets pulled out their guns as if out of nowhere. Guns? People close to César say that evening was definitely a game-changer for him because Ellen was powerfully convincing and she got him thinking about becoming a vegetarian and to become more disciplined about what he put into his body; she even encouraged him to practice yoga. He remained in occasional contact with her talking for long hours (as evidenced by phone bills brought to his attention by Fred Ross, an ardent UFW organizer and volunteer accountant) about nutrition and health as he knew she was a well-disciplined individual and he respected this about her.  Sonny Boy Arias, a dedicated contributor to Somos en escrito via his column, Chicano Confidential and a stone-cold Chicano, has returned on hiatus while on a world tour of Europe and the Subcontinent telling stories or mentiras as the spirit struck him (several times). He writes under the general rubric of historias verdaderas mentiras auténticas–true stories and authentic lies. He has found this the most effective manner to convey his stories about Chicano life. Copyright © Arts and Sciences World Press, 2018.

0 Comments

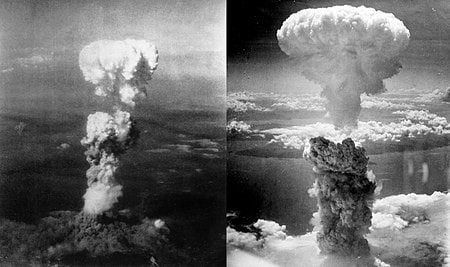

In the Time of The Bombs: |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed