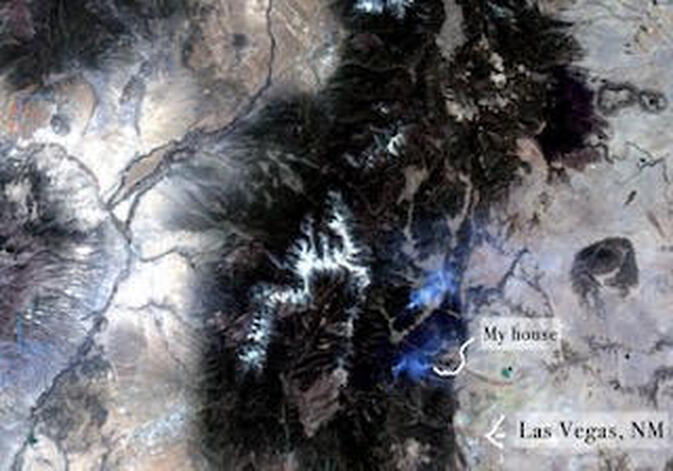

“A Good Day to Die”by Gloria Delgado Preliminary Witness Statements Late afternoon: Tuesday 10/10/23, single vehicle accident on I-25 near Glorieta, about 5:30 p.m., still daylight, no weather problems, light traffic; subject vehicle, a Toyota FJ Cruiser, driving the speed limit in right lane, observed by multiple witnesses to suddenly collapse onto its right side, spin out of control, slide across both lanes; front end dips into median culvert which causes vehicle to flip over at least twice more across opposing traffic lanes, come to a stop in upright position off road, facing oncoming traffic. Four adult occupants all wearing seat belts, and a dog. No visible injuries. *** The last thing I remember clearly that afternoon was the sound of my son’s voice, calm and collected as always. “Something feels wrong with one of the new tires, so I’m pulling over to the side as soon as…” And then everything turns dark. I open my eyes to see the right rear passenger window next to me shattered into dozens of shiny bits of glass, almost like a mosaic, reflecting varied shades of blue, green and black, gray and brown. A sagging net or membrane holds all the now separated sections of glass loosely together. The blue must be the sky, but the gray and black? Oh, that’s the color of the road, the asphalt of the highway. The car is sliding towards something close by, the edge of the road, or maybe the culvert that divides the opposing lanes of the highway? Whatever happens, into the culvert or over the edge, it will be interesting. Wait and see, just wait and see. No fear. But how can I see through the shattered window? And why does everything seem upside down? An old expression, “topsy-turvy,” comes to mind. Does anyone really say that anymore, or even understand what it means? My mind is active but calm; there’s all the time in the world to think logically about what is happening, while outside the car’s concurrent slide towards the edge of the road seems slow, unending, interminable. I can see the approaching highway edge because a portion of the mosaic window is missing. Ha, that’s actually funny, the window has a window of its own! I open my eyes wider to a sudden alert on my new watch, a gift from the same son, warning, “It looks like you’ve been in a crash,” with further instructions, but I’m unable to respond. We’re about to die. Or live. Wait and see. No fear. And everything turns dark again. But what’s wrong with dying? Every living thing must come to an end. “It’s a good day to die.” Where did that line come from…an old ‘70s movie, wasn’t it? One with Tom Cruise…no…Dustin Hoffman! Little Big Man, that’s the name. Now I remember, the phrase, credited to the Lakota people, was spoken by Chief Dan George, who played the elderly Indian. My brain is still calm, my eyes still closed, I’m waiting to see if I live or die, and here I am thinking about movies. How stupid! If I survive maybe I’ll write about this, but no one’s going to believe me. Tradition insists on us experiencing profound solemn thoughts at death, not ones about old films! Out of the darkness comes the buzz of voices, the whine of distant sirens, someone sobbing, anxious people hovering. “My God, they must be dead, how could anyone be alive after rolling like that!” “No, look, she’s in shock, but still alive, all four of them are still alive, they were wearing seat belts, she can even walk by herself!” They’re talking about me, I realize. Multiple car doors open, slam shut. The soft gentle touch of a woman guides me into another vehicle where I sit, shivering, but not with cold. It must be a small car, not an ambulance, as I get in the back easily without a stepstool. She wraps something around me, a blanket, or maybe a jacket, but something warm and comforting. I still can’t open my eyes. Motion, commotion, scurrying, activity, blaring sirens, excited voices, rumbling motors, more slamming car doors, jagged rough sounds of metal (car doors?) being pried open. It’s all too much. For a few brief seconds I open my eyes, see my husband outside, waiting, sitting on a nearby car’s bumper, looking worried, dazed; but thankfully he doesn’t appear injured. No blood anywhere. Then he gets up, walks around the car, out of sight. I try calling to him, but no words come. My son’s voice cuts through the confusion. “Mom, we had an accident. For some reason, I don’t know why, the two right tires burst one after the other, even though I just had them looked at! That flipped the FJ on its side, we slid across the freeway, hit the edge of the culvert, turned over about two or three more times, then slid across the other lanes. But nobody seems seriously hurt, just bruises, maybe a few broken bones. Paramedics are here to check us out.” “Are you sure, you’re not just saying that to make me feel better? And what about the dog, is she ok?” “No,” he answers, “it’s true, everyone, even Coco, made it.” “And what about your father, will you find him for me? He was here a moment ago, walking around, but I don’t know where he went.” A different woman interrupts, waggling her hand in my face: “How many fingers am I holding up?” Leave us alone! How can I count if you keep moving? That’s what I want to say, but instead guess, “Three,” just to shut her up. I can’t seem to, or want to, focus on her hand or on her fingers. Turning back to my son, I again ask him to look for his father. “Mom,” he answers, in a strange, strained voice, “Dad is dead, he died late July in the hospital, remember? We just held his funeral! There were only four of us in the FJ, you, me, your brother, and your sister-in-law. And Coco. Dad wasn’t with us.” I insist: “He was here, I just saw him!” A pause. Now I remember, my son is right, Dave is dead, but I know he was at the accident scene. I saw him! My eyes fill with burning, unshed tears. I’ve lost him again! My son speaks softly to the paramedic, but I can hear him despite the rapidly engulfing shadows. “She may have some memory loss or brain damage because…” And everything turns dark once more. Another broken window? No, I briefly awaken to a chill wind, vibrations, whirring blades, a large open space, maybe the door, not the window, of a…helicopter? How strange. Last night I was flying home from Canada, riding in the first-class section because of an unexpected upgrade, and now this. What happened? Oh - the accident. It must be very late, because the open space is cold, dark, full of stars. Damn! I’ve always wanted to ride in a helicopter, but not this way, I can’t see a thing! Startled awake…It’s about 3 a.m. by my watch, I’m now lying on a narrow metal bed, tethered by multiple tubes and wires to an upright rolling stand holding blinking medical equipment, listening to a complex array of irritating sounds. Outside, distant sirens, the squeal of a car doing ‘donuts’ in a nearby parking lot; inside, a mix of clicking, beeping, clattering machines, weeping voices crying out for their mothers, quick laughter, hushed chatter, the sudden too-bright flash from a partially opened door just as quickly shut again, unanswered signals calling for help. Obviously, I’m in a hospital, but what happened in all those in-between hours? And where are my brother and sister-in-law? There’s no one around to ask. I gradually fall asleep feeling no real pain, except for a slight but increasingly bothersome headache, a few new sore areas on my shoulders and hips, blurred vision in one eye. My glasses are missing. Morning’s warm light shines through the narrow window of a hospital room crammed full of relentless buzzing equipment. My son is there, waiting in one corner. His welcome voice cuts through my confusion to fill in missing gaps in time and memory. I’ve been diagnosed with multiple intercranial subdural hematomas and two (re)broken lower vertebrae. My brother and sister-in-law are out of danger, with several cracked ribs each, but my son is unharmed, the dog, too. That helicopter ride was not an illusion. When a neurosurgeon was unavailable at the nearest hospital in Santa Fe late that first night, they transported me by medivac to a hospital in Albuquerque. Two days later, after being fitted with a brace to protect healing ribs, and after another long delay in finding a surgeon to sign off discharge papers, I’m finally released. My son is there to take me home. We find the missing glasses tucked in one of my shoes. The first thing I do at home is review and alter my ‘end of life’ choices from hospitalization to hospice. Although it had seemed “a good day to die,” and I felt ready, as with Chief Dan George it wasn’t to be, not just yet. I had been granted more time on earth, more time to finish pending tasks, to reconcile problems and connect with family and friends. Ultimately, I was grateful, although to be honest, most gratifying was just getting away from all the infernal noise, away from that relentless beeping of impersonal machines. Whatever happens, it will be interesting. Wait and see, just wait and see. No fear, just a wish and a prayer: May God grant me a peaceful serene death at the end of my time.  Gloria (Calvillo) Delgado, born and raised in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district, is the daughter of a Mexican father and a Hawaii-born Puerto Rican mother. She and her late husband David lived for many years in Albany, California, where they raised their family. One of her stories, “Savanna,” was included in the Berkeley Community Memoir Project's recently published collection, “A Wiggle and a Prayer.” She has had four stories printed in Somos en escrito, including “El Parbulito,” a first-place winner in Somos en escrito’s 2019 Extra Fiction Contest and included in El Porvenir, ¡Ya! - Citlalzazanilli Mexicatl - Chicano Science Fiction Anthology. Recently widowed, she now resides with family in a rural community outside Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she has resumed writing.

0 Comments