|

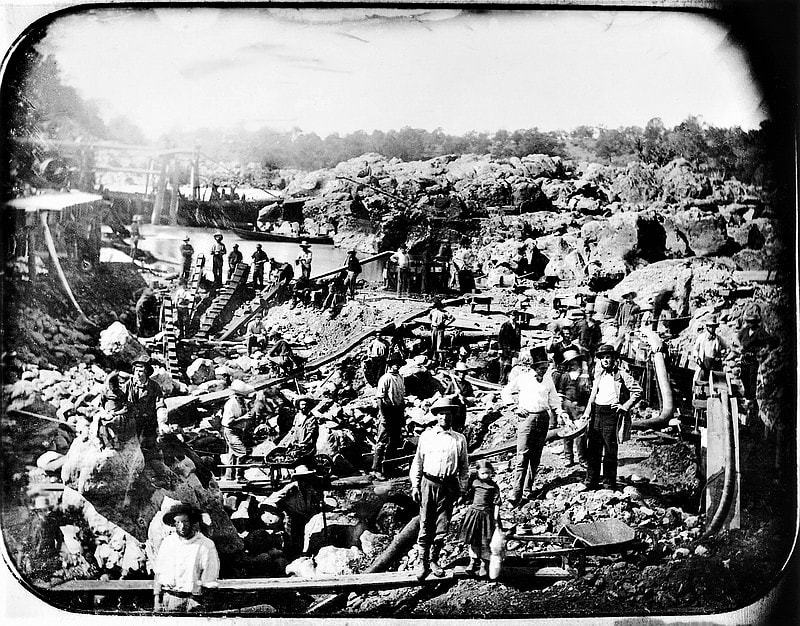

Spring Valley Elementary School, circa 1950 Photo credit: SAN FRANCISCO HISTORY CENTER, SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC LIBRARY https://sfpl.org/locations/main-library/historical-photographs Master Teacherby Gloria Delgado Author's Note: All names but mine have been changed. I was 21, had earned my BA in Spanish at the San Francisco College for Women (aka Lone Mountain College), and was now working through my student teaching requirements with the goal of earning an elementary credential. Adding to the normal pressures and challenges involved, I was also overwhelmingly aware that, if successful, I would supposedly be the first Mexican student from Lone Mountain to earn a teaching credential. This made me a role model for some of my Latina lower classmates, who constantly questioned me about the realities of student teaching. They were trusting in me, relying on me to help them through the same experience. I was also engaged, and planning a late December wedding. Lone Mountain’s education department, although well-intentioned and nurturing in many ways, was still mired in the outmoded attitudes and mores of the 1940’s and false façades of the 1950’s. Our professors sometimes put more emphasis on proper appearance and demeanor, what we students called their “tea, hat and white gloves syndrome,” than they did in preparing us to deal with the actual education system. Student teachers had no written code of rights or duties, only unclear and nebulous obligations. One huge failing was that we had to complete our student teaching, one or more years at best, before even stepping into a classroom. Our entire education system was completely unprepared for the changing times and upcoming social turmoil of the 1960’s. The first half of my student teaching had been a delight. I loved being part of that third-grade classroom of students from Grover Cleveland Grammar School. My master teacher, a warm-hearted and generous woman, had encouraged and advised me, giving me many opportunities to work with individuals or with the entire class, a chance to develop a rapport with the children. I was even assigned a special project, working with a young Chinese boy who refused to speak in school. At the end of my time this master teacher and other reviewers gave me an excellent evaluation, and she and the students said their goodbyes with embraces and best wishes for the future. Enthused with how my experience had gone so far, I was eagerly looking forward to my second half of student teaching, this time in the middle of San Francisco’s Nob Hill and Chinatown neighborhoods. My next assignment would be Spring Valley Grammar School's fifth-grade classroom, and my new master teacher, Mrs. Butler. Spring Valley School had a long and troubled history. The oldest existing public school in San Francisco, first established around 1852, then relocated and rebuilt at its current address after the 1906 earthquake, during its early years was reserved for whites only. When in 1885 a young Chinese girl, Maggie Tape, won a California Supreme Court suit for the right to attend Spring Valley, the San Francisco School Board simply kept her name at the bottom of a never-ending wait list, and built another public school to accommodate “other” races. The Tape family finally moved across the bay to Berkeley so Maggie could attend school there. I knew something of the school’s history, but this was now 1962, and I was comfortable with the assignment and with the area. It was the neighborhood where my paternal grandparents had lived, met and married in 1904, and the narrow, steep streets and crowded neighborhood were familiar to me. Getting to the site involved a long commute, two buses plus cable car, then a stiff walk up and down hills all while wearing skirts and heels, as required by Lone Mountain’s strict dress code, which forbid the wearing of jeans or slacks and required high heeled dress shoes. Anything else would have been considered inappropriate or unprofessional attire. Situated in the middle of the block, surrounded by old wood houses and stucco apartments, Spring Valley Grammar School was a several-storied brick and cement building with large windows and stone half-columns at the front entrance. Around the structure were narrow asphalt play areas barely big enough to hold all the students at recess or lunchtime. I don’t remember a cafeteria. Half a block up from the school on one corner was a small Chinese restaurant; at lunchtime both students and staff formed long lines outside, waiting to buy a plate of rice or noodles, vegetables and meat. For two dollars, one order provided enough lunch for several to share. At this time the school population was about 98% Chinese; the principal, teachers, yard supervisors, secretaries were all white females. The only adult male at the school was the janitor, also white. I signed the log-in book before meeting with the principal, Mrs. Mitchell. She welcomed me with a warm smile, escorted me to the fifth-grade classroom, introduced me to Mrs. Butler, my new master teacher, then left. Upon the principal’s departure, Mrs. Butler appeared somewhat imposed upon by this unwelcome intrusion, this interruption of her routine. She coolly, slowly looked me up and down with what seemed barely disguised contempt, then introduced me to her students. “Class, this is Miss—What did you say your name was?—Of course. Miss Colville, Miss Cavi—How do you pronounce that again? Oh. Yes. Miss Cal-vee-yuh, who will be with us for a few weeks. She wants to learn how to be a teacher.” Then, in an undertone, I was dismissed: “Go to the back of the classroom, take a seat, and just watch what I do.” “Just watch what I do.” And that’s all I did, three half-days a week, for what seemed unending hours; I watched her do whatever she did—but without taking a seat. There was no chair, no stool, no extra desk for me to use, and none was ever provided all the months that followed. I was not allowed to speak with or interact with any of the students when Mrs. Butler was present. Banished to “the back of the bus,” as it were, I stood in uncomfortable high heels in a corner by one of the two doors to the cloakroom or leaned against the middle of the wall. These initial long hours of standing and watching did prove valuable. By moving casually from one side of the classroom to the other, I managed to get glimpses of the students’ faces, and in three days came to know them all by name and personality. This was the era when the Asian school population, still labeled “the model minority” by 1950’s society, had names like Alexander, Lily, or William; none used a Chinese given name in school. All the fifth graders at Spring Valley School were attentive, polite, clean, neatly dressed, healthy, and apparently happy; that is, all except for one—Marcella, the only white girl in the class, the only white girl in the entire school. Mrs. Butler was a slightly stout, imposing woman in her late 50’s with meticulously waved short dyed blonde hair, icy blue eyes, and perfect makeup. Not one for riding buses and cable cars, she rode to and from campus in a Yellow Cab, arriving and departing always on schedule. Impeccably, even modishly attired, she would sit unmoving behind her desk for long periods of time, on occasion rising majestically from her chair to write on the chalkboard or to lecture. Everything about her was carefully controlled—her appearance, her demeanor, her voice, her movements. Mrs. Butler never rushed, never raised her voice in excitement, joy, or anger; everything she did was dignified, reserved, calculated. Her teaching style, lectures, even her occasional compliments to the students acknowledging good work or a successful grade, were muted. The fifth-grade classroom was attractive, a large turn-of-the-century style square high-ceilinged room filled with rows of wooden desks lined up in orderly fashion. On the left side of the room light streamed through several huge waist-to-ceiling stacked wood windows that had to be opened or closed against the changing weather with a long wooden pole, an iron hook on one end. Leafy green plants, cared for by the students, sat on the wide windowsills. On the opposite wall were two doors with transom windows. Black chalkboards covered the remaining space. A dark upright piano, apparently never touched, stood in one corner of the front wall. At the rear of the classroom was the cloakroom, a door at each end. Maps, globes, flags, some bookcases, a black clock hung high filled the space. The large oak desk presiding at center front was topped with neatly stacked books, notes, daily lesson plans. A slender vase by the handbell occasionally held flowers Mrs. Butler or a student would bring, pastel blossoms, a white camellia, or a sprig of the dainty pink sweet-fragranced Cécile Brünner roses that once flourished throughout all old San Francisco neighborhoods. But the most notable article on Mrs. Butler’s otherwise nondescript desk, the only object reflective of Chinese culture in the classroom, was the reclining figure of a jovial Chinese god with a bald head and fat round belly. This large carved wooden figure was obviously valuable. Placed to the far-left front edge of the oak desk with his back to Mrs. Butler, the laughing god faced the rows of student desks. “Who is this? Is this Buddha?” I seized the opportunity to ask the class one day when Mrs. Butler was called out for a moment. “Why, he’s not Buddha, he’s the Laughing God, Budai,” the children, now surrounding me, eagerly explained, “the god who brings good fortune. His big bag holds everything we need for everyday life. He’s the happy god who protects all his children. Rub his belly,” they insisted, “it brings you good luck!” And so, I rubbed Budai’s belly daily, asking for protection and good fortune for the children; and for me, the strength to get through another day watching Mrs. Butler. *** Later one afternoon Mrs. Butler and I were alone in the classroom when she asked, with no preamble: “Where were your parents born, Miss Cal-villee-yuh?” Knowing this was code for …what are you, I can’t figure you out, and not knowing really bothers me… and offended, not by the question, but by her manner, I deliberately and literally answered the question she asked, and not the question she wanted to ask. “My father was born in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, and my mother on Ewa Plantation, Oahu, Hawai’i. “Oh, so you’re Hawaiian! No wonder you look so exotic!” “My mother is not Hawaiian, she is Puerto Rican, born in Hawai’i because that is where her parents were living at the time; that makes me Mexican and Puerto Rican.” Then, still feeling the sting of her irritating use of the word exotic, in a not very subtle attempt to redirect the conversation I asked her about the figure on her desk, not revealing that the students had already introduced us. “It was a ‘welcome to our school’ gift given to me by the Chinese parents when I first started teaching at Spring Valley.” Her bland, rote monotone response to my question lacked warmth, a sense of gratitude, enthusiasm, or sensitivity to what Budai obviously meant to her students and their families. They had given her part of themselves, part of their culture. Did she see Budai as more than just a block of wood, did she understand, did she even care? No. She had referred to Budai as it, not as he. Then she said: “You know, dear, you really should smile more; you would be so much more attractive.” I was put firmly back in my place. Mrs. Butler turned and sat down at her desk; the children returned from recess; lessons resumed. Reflecting later on our exchange, I had the strong overwhelming intuition that Miss Butler intensely disliked the figure of Budai, finding him too exotic, too foreign—like me. But the figure was something she could not easily dispose of, not if she wanted to keep her job and the approval of the parents. Budai and I both might be thorns in her side. One thought followed another. Did she dislike her job? Had society changed too quickly for her, made her feel trapped at Spring Valley, helpless, unwilling, unable to adapt or cope? Did she even like her students? I already knew, even after a few days, that she intensely disliked, possibly even hated me. Did she, deep inside, dislike her students? But why? For being unworthy of her talents? For being different, exotic, Asian? These unwelcome intuitions of mine were sickening and ugly; and I tried to suppress them. Still stunned by their impact, stomach churning, thoughts and speculations reeling, I took up my usual post standing at the back of the class. *** Some of the other teachers would occasionally talk with me when I spent time in the faculty lounge; for the most part I was ignored. “Oh, so you’re the new student teacher” was the comment I heard most frequently that first week. “Hmm… You know, of course, that she didn’t want another student teacher. You were forced on her, just like the previous one, that young black woman. She didn’t last long either, poor thing.” And when Mrs. Butler walked into the lounge the conversation instantly shifted, and I became invisible. With time enough to reflect on what had been said, I realized that Mrs. Mitchell’s accompanying me herself to Mrs. Butler’s classroom, and her introduction of me to Mrs. Butler in the presence of the class, was not the generous, friendly gesture I had initially taken it to be, but was the outcome of a clash of wills between the two women. And Mrs. Mitchell, as principal, had won that particular battle. Mrs. Butler could not easily dispose of me if she wanted to keep her job and the goodwill of her employer. On my way home one afternoon that same first week I was headed to the front entrance when the janitor, still carrying the mop and bucket he had just used to clean the floors, called out to me. “Miss! Say, Miss! You the new student teacher?” he asked, turning his head back and forth, apparently checking the hall to see if anyone else was around to hear. I nodded, uneasy, unsure where this was going. “Watch out for her, that damn bitch, she’ll try to do something to you, she’ll try to hurt you.” “Who will?” But I already knew the answer. “Butler, of course, who else!” He smirked, looking me up and down, appraising me almost as coolly as Mrs. Butler had done that first day. This one won’t make it, either… Shaken, but attempting to conceal it, I only nodded, gave him an icy “Thank you,” knowing that a new student teacher shouldn’t be seen alone in conversation with a janitor. I left for home, thinking: I know she dislikes me, but what could she possibly do to me, and why should she bother? I’m nothing but a very small temporary thorn in her side. At first, in an attempt to bring down the barriers between us, I tried to engage Mrs. Butler in conversation during the breaks in the teachers’ lounge. I assured her of my willingness to tutor students needing assistance with math problems or reading, to help with anything, anything at all. But the days went by; nothing worked, nothing changed. She terminated any thought or suggestion of mine with the same admonition: “No. Just watch me and see how it’s done.” *** Two weeks into the semester, while in the office signing the attendance book, I was surprised to see a familiar face. Mary Henley and I had been through grammar and high school together. “I’m the fourth-grade teacher now,” she told me, and after learning I was the new student teacher, she whispered: “I’ve got to leave now, I don’t want to be late, goodbye,” then abruptly turned and went off down the hall to join her class. What was that all about? Although we were not friends, we had always been on friendly terms, and there was still plenty of time remaining before the first bell. Mary was a shy and quiet person, but to witness this timid, even fearful behavior of hers was unsettling. Was it the mention of Mrs. Butler as my master teacher? I never spoke with Mary again, and only caught occasional glimpses of her across the auditorium during school assemblies. Mary never joined the others in the teachers’ lounge, never lined up for lunch at the corner, never seemed to leave her classroom. I wondered what, or who, she was avoiding besides me. It would have been nice to have someone to talk with, to see a friendly face, to have an ally. It was all so strange; Mary too had almost disappeared, become invisible. Was Mary afraid of Mrs. Butler? I would never know. Something was very wrong here; was it the school, was it Mrs. Butler, or just me? *** “Just watch what I do.” And so, I continued. Standing, I watched her for days, then weeks on end, gradually learning that something was indeed wrong, but it was difficult to describe at first, difficult to put into words. Yes, something was wrong, and it seemed to begin here, in this classroom. I watched and learned. Mrs. Butler did nothing overt, nothing that would ever leave her open to criticism. Her interactions with the students were to the casual outside observer always pleasant, mellow, full of compliments. She was not one to lose her temper. She was always so subtle in her methods, in her cruelty. Mrs. Butler’s particular type of cruelty was new to me, and difficult to describe. It was not what she said or did, but how she said or did things, with an ease far beyond my experience. Most of the wounds she inflicted were quick tiny jabs, like mosquito stings, almost invisible on the surface, but nevertheless capable of leaving behind deep and festering infections. Mrs. Butler pretended not to notice the effect her hints and insinuations had on the students; but I noticed; I watched. She always said and did things deliberately, never carelessly, or half-way, or by accident. Her techniques were not as effective on the boys who, at this still mostly innocent age of nine or ten, more easily managed to ignore them or shrug them off. Anyway, Mrs. Butler seemed to prefer to manipulate the girls. This morning, Louise was her focus, her tool. “Look, everyone, Louise is so pretty today in her new dress! Louise always looks so nice, her clothes are always so beautiful!” All eyes turned as one to gaze at Louise, who, head down, hands clasped together in her lap, smiled modestly, basking in the compliments. Subtly made conscious that Louise had …something… that they lacked, the other girls’ eyes, glazed and clouded, went blank for long silent seconds. The girls were still too open-hearted to actively dislike Louise, or Celia, or Sara, whoever was singled out to be complimented for the wrong reasons, whoever happened to be Mrs. Butler’s chosen focus, her tool, the target around whom she created and fomented negative feelings within the group. They didn’t actually dislike each other, not yet; but I could sense dislike and jealousy and hubris building and growing, little by little, created, cultivated and maneuvered by Mrs. Butler. Louise in particular didn’t need to hear such frequent compliments. The treasured daughter of a comfortable family, Louise was a nice girl, a beautiful child who always arrived at school wearing expensive new dresses, her long straight gleaming black hair carefully arranged and tied back in bright ribbons. Excessive praise, and being singled out for her attractive appearance day after day could only do her harm—but could this really be Mrs. Butler’s goal, to cause harm to Louise, to the children? I was stunned, ashamed of my suspicions. They filled me, nevertheless, and couldn’t be ignored. Marcella, the only white child remaining in the ever-shifting class, was Mrs. Butler’s most frequent target, the daily recipient of twisted compliments. Mrs. Butler hardly bothered to disguise the scorn and contempt she felt for the girl. Perhaps she considered Marcella to be too simple, too easy a target, and unworthy of her subtlety? The daughter of a poor family, this clumsy, gangly girl was never complimented on her dresses, never came to school wearing ribbons. With her blonde hair chopped off just below her ears, ends carelessly pulled back in a rubber band, she was always dressed in clean but threadbare old clothes. She spoke, when pressed, with a soft southern country drawl. Apparently still in the awkward stages of early puberty, a full head taller than her classmates, Marcella lacked the easy grace and charming manners of her quicker, more coordinated, more sophisticated classmates. Mrs. Butler began: “Look, everyone, Marcella has finally managed to—finish her work on time—make only three mistakes on her test—skip rope for one minute before tripping—get a C—catch the ball and only drop it once…” Every day brought fresh opportunities to single out Marcella in this negative way. Today it was a class game of basketball. “Look, class, Marcella finally threw the ball into the basket! She found the basket! Let’s everyone clap for her. Yeah, Marcella!” “Yeah, Marcella!” the class parroted Mrs. Butler, clapping in unison, in bored, orchestrated applause lasting only a few seconds. The unfortunate girl, hair coming loose from the rubber band, strands flying out in all directions after her strenuous efforts, and horribly embarrassed at this additional reminder of her general ineptitude, looked down at the ground, her body writhing, her mouth twisted into a caricature of a smile, the toe of one worn shoe grinding into the ground, as if digging an imaginary hole in which to hide. The bell rang, the children gathered to return to the classroom. Marcella paused, hanging behind, waiting to take her usual place at the very end of the line. Angry thoughts filled my mind: Marcella will bloom at her own time, but this woman just won’t let her alone. Why does Mrs. Butler hate her? Does Marcella remind her of herself at that age? Is it because she is the only white girl in the school, and Mrs. Butler is ashamed of the girl’s poverty, of her shabbiness? Could it simply be that Marcella’s hair is naturally blonde? It was cruel of her to constantly single out Marcella this way, and exceedingly painful to watch it being done. I could do little about it but gently touch the girl’s shoulder, smiling at her after everyone else had turned away. “You did very well today, Marcella,” I whispered. She lifted her head and looked straight into my eyes. My reward was one of her genuine, sweet smiles. *** My time at Lone Mountain was becoming more and more stressful. I felt tremendous pressure, receiving little help and even less guidance from an unsympathetic and clueless education staff. When I tried to describe the poisonous atmosphere at Spring Valley to my supervisors, they thought it was mere complaining. They didn’t even hear me. After all, Mrs. Butler hadn’t done anything wrong, not really. No one had done anything to me, not really. “We’re sure things are fine, dear. She’s your master teacher after all, she must be happy with you; if she weren’t we would have heard. There’s still plenty of time left for your evaluation. Don’t worry so much. Just be patient, cooperate, do your best.” Platitudes, empty platitudes, with no insight, no empathy, no understanding. I was sick of it. During my two days a week back at college, the younger Latinas questioned me relentlessly. They wanted to hear the truth, not platitudes, not empty phrases. They needed to know exactly what I was experiencing. It was all up to me to tell them this truth, that it wouldn’t be easy, that many people were out to block us in any way possible. My goal, my future, my classmates’ futures and hopes were at stake; and everything was slipping away. I was their symbol, their apparent leader, and I was about to fail. *** Tired of watching Mrs. Butler, suddenly one day something within me snapped; it all became too much to bear. No more! I’ve had enough, now it’s my turn, you will start watching me! I did nothing overt, nothing disrespectful that would leave me open to criticism, but I would not give up, crawl away or hide. Too much was at stake. I would not become her focus, her target, another Mary Henley. Now, my father’s favorite saying again came to mind, and I took up the challenge, followed his imperative. “Jalisco, no te rajes! Jalisco, never give in!” Now, I crossed from one side of the room to another, moving only when Mrs. Butler’s attention was elsewhere. It was petty and childish, but I did it anyway just to annoy her. Before, I had always entered the classroom by creeping in the back door like an intruder, rubbing Budai’s belly only when there were no witnesses. No more. Now, entering by the front door, I deliberately crossed the classroom directly in front of her desk, now I wished her a cheerful “Good morning,” now I greeted Budai with a quick rub of his belly before taking my usual place in the back. The students may or may not have noticed, but she certainly did. Ignoring her glares, subtly daring her to admonish me, I started greeting and addressing the students by name when we lined up for recess, gathered in the playground, or made trips to the assembly hall. In spite of knowing she would ignore me, nevertheless several times a week I would politely ask the same questions: “When will I be allowed to teach a lesson, to help the students? And my evaluation, when will it be scheduled?” I began writing in a small notebook while Mrs. Butler lectured, jotting down nonsense things, random thoughts, anything to keep from going insane, to keep the classroom walls from closing in on me. That little notebook would become my refuge, a safety net. My stomach would hurt once in a while, but I ignored it. One morning, in an excess of boredom, I grew careless. Standing at my usual place beside the back wall, I was writing some nonsense in my notebook, eyes focused on the paper, when Mrs. Butler suddenly appeared in front of me. It was dizzying and disorienting to see her any place other than the front of the room, as though the earth’s axis had tilted. “What do you keep writing in that book of yours? What do you have in there that’s so important?” she demanded. Yes! Finally, I had gotten to her! “Oh, nothing really important,” I coolly, glibly lied, “just random thoughts that occur to me. I note down good methods or techniques you use to teach, ideas for lesson plans, things you do that are effective, stuff like that. Would you like to see?” I offered her the open notebook, certain she would refuse it. Mollified, she shook her head no, returned to her proper place in front of the classroom. Oh my God, I knew it! She believed me! She won’t ask about the notebook again. But maybe I was watching and learning too well. The idea of beating her at her own game for a moment had felt strangely challenging and appealing to the ego. Hubris? And what about my classmates who were depending on me? Being in the same room with Mrs. Butler was changing me into another person, into a liar, a sneak, someone I didn’t much like. It was making me sick, emotionally and physically. That ball of discomfort in the pit of my stomach kept growing larger. So, I jumped at the chance when Mrs. Butler unexpectedly asked me for a favor. The aide who usually supervised the playground at lunchtime was out on sick leave and would be missing for about one week. Would I be willing to take her place? “Of course, I’d be happy to help!” From then I spent every lunch period in the schoolyard. It was a relief to be outside interacting with students, removing wood splinters from little fingers, mending petty squabbles, wiping away tears. I could breathe again. The only problem was missing lunch; there was no time for me to eat. Two weeks went by, then three. I asked, but was told: “No, the aide is still out.” And like a fool I believed it, until one afternoon I happened to see the supposedly ill aide chatting comfortably in the lounge. I don’t remember who told me that the aide was still getting paid for the work I was doing; but by this time playground supervision had become my regular responsibility on the three half-days a week I spent at Spring Valley. I wondered if the aide and Mrs. Butler had colluded to get me to take her place for free? The principal must have known about this, must have approved this. What would Mrs. Butler get out of using me? Power? Revenge? Secret satisfaction? *** One morning around December 7th, Mrs. Butler’s stone façade seemed to crumble. Having just finished a regular lesson on the significance of the date, the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, she remained seated, uncharacteristically still. The silence continued for long moments, disturbed only by the ticking of the large black clock on the wall. Out of the silence she burst out: “I hate the Japanese! I hate them! They killed my brother!” The class sat stunned, mouths open, eyes darting back and forth. I looked on anxiously, feeling another huge lump forming in my stomach. Her body shaking, hands trembling, face ashen, Mrs. Butler then graphically recreated the bombing of the battleship Arizona, ending with a detailed description of the 1,100 bodies remaining behind entombed within the ship, among them her brother. Her account finished, Mrs. Butler slowly rose from her chair and walked out the door—just as the bell rang for lunch. I forced myself to move to the front of the class and dismiss the children, who had remained frozen in their seats, shocked into uncustomary stillness. What should I do? Should I report this episode to the principal? Report what? It was horribly wrong for a teacher to expose young pupils to such strong personal emotion. It was a terrible abuse of her position! What was my own responsibility here? Confused, sick with anxiety, already late for yard duty yet truly concerned for her well-being, I quickly checked the halls, lounge, and restrooms, but Mrs. Butler was nowhere to be found. I gave up the search and went outside to the playground. After lunch Mrs. Butler was back in the classroom as usual, her composure and demeanor normal, showing no sign of emotional trauma. I approached her, told her how sorry I was for the death of her brother. She ignored me, making me invisible again. I walked back to my customary place and position at the rear of the room, just like Marcella always at the end of the line of students. Once again watching Mrs. Butler, with time enough to reflect on what had transpired, the intuition struck me that this whole episode was a cold, calculated performance--but to what end, to what purpose? What kind of sick, twisted person would use her brother’s death this way? …and it was twenty years after the fact …and her exit had been so perfectly timed… Did her brother really die at Pearl Harbor? Did she even have a brother? Did she do this every December 7th? Was the performance, if indeed it had been a performance, solely for my benefit, to see what I would do about it, to see if I would report her? She could easily deny the whole episode, turning me into this suspicious, libelous student teacher trying to draw attention to herself. Or was I becoming cruel, mean-spirited and evil, daring to suspect the worst of a severely traumatized, unfortunate woman? Or was I being manipulated, like Marcella, like Louise? Were the children being manipulated and victimized out of her sadistic need to inflict cruelty and pain? But why? Because she hated me? Because she hated them? Because they, like the Japanese, were Asian, and easy targets? Nothing made sense. I tried to suppress my suspicions and my intuitions but failed. I didn’t want to have such thoughts about anybody, not even about Mrs. Butler, but they existed, and couldn’t be ignored. I didn't know what to do. After hours of inner turmoil and confusion, still unsure and uncertain, I decided to wait, to keep quiet about the whole event in case I was being manipulated. Again, my stomach hurt. *** Shortly after my assignment to Spring Valley I had informed Principal Mitchell that I would be getting married during the Christmas break and would like to take off one extra week in January for a honeymoon. She had agreed, as long as I fulfilled my hours. It was settled; after my return I would be at school three whole days a week until the end of my school term and would continue with yard duty, more than fulfilling the number of hours of my obligation. No mention was made of pay. It was now mid-December, time for Christmas vacation. The children showered me with gifts, boxes of candy, brightly colored tins of tea, and cards. When I reminded Mrs. Butler that I was getting married soon, she coldly told me to announce it to the children myself. For the first time in all those weeks at Spring Valley School, I was allowed to stand in front of the class. Telling the students that they were all invited to my wedding at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church on Broadway Avenue, just a few blocks away, I jotted down the address, date and time of the ceremony on the blackboard. When I glanced at Mrs. Butler out of the corner of my eye, she was frowning. Once again I had gone too far, had overstepped a boundary. But it didn’t matter, I didn’t care, I was getting married, and getting a welcome break from watching Mrs. Butler. With a rub of Budai’s belly, I asked him to watch her and to protect his children. They remembered. They came to our wedding! It gladdened my heart to see a group of fifth graders sitting quietly together in the rear pews. Unaccompanied by any parent, confident, dressed in their best, the children had come to the church together, and had patiently sat through the whole Mass and ceremony, in spite of it being celebrated in Latin and Spanish! When my new husband and I stepped outside after the recessional, we saw more fifth graders gathered together across the street from the church, jumping up and down in excitement, waving and calling out “Miss Calvillo! Miss Calvillo!” We waved back, honored by their presence. When I returned to Spring Valley it was the middle of January. I had the same lengthy commute—two buses, a cable car, a long walk—but now my first bus ride started in Berkeley, our new home, and took even longer. The children seemed glad to see me again, and I realized how much I had missed them. “We saw Miss Calvillo getting married,” I overheard several students whisper to their friends the day I returned. Mrs. Butler now addressed me as Mrs. Delgado and seemed to have no difficulty pronouncing my new name. Otherwise, things continued as before, but now I had entire days, three whole days a week to watch Mrs. Butler. She had not changed. She continued to evade the issue of my evaluation and kept me to my usual place standing at the rear of the room, still without a chair. That ball of pain at the pit of my stomach came back larger than ever. The following weeks seemed interminable, a blur of quickly passing memories; only one small incident stands out. Mrs. Butler announced: “I want to share some good news with you, class. I just found out that we will all be together again next year. I’m going to be your sixth-grade teacher! Isn’t that wonderful?” There was a long, long pause while the children took in her message. “Yeessss… Mrs. Butler,” slowly came the ragged, unenthusiastic, not quite in unison response. My heart sank. One more year of this, of her? I would be free shortly, but the poor children… *** It was mid-afternoon, almost time for the music lesson, when Mrs. Butler beckoned me up to the front of the class. “I need to go to the restroom, Mrs. Delgado; I’ll be back shortly.” Mystified, I stood there watching the children as they talked quietly among themselves. Was she sick? She didn’t look sick. What is going on, what is she up to now? With a tremendous jolt to my stomach, I understood: My God, this has to be my evaluation! And with no advance notice, no chance for preparation! She was about to prove me to be this incompetent, unreliable and unstable student teacher, the one she had said all along couldn't handle the pressure, poor thing, the one who fell apart at her evaluation. Moments passed. Wearing a wide, triumphant smile, Mrs. Butler grandly entered the classroom, trailed closely by Principal Mitchell and two unfamiliar women. Too stunned to hear their names, I managed somehow to smile as we all shook hands and introduced ourselves, but I never heard a word beyond “We are here for your evaluation.” My thoughts reeling, stomach churning, I tried to formulate a lesson plan, any plan, out of nothing. Then Budai, the protector of children, the bringer of good luck, smiled on me. I needed a lesson plan. Laughing, he opened his sack, the bag that holds everything his people need for everyday life, pulled out a lesson plan, and placed it, complete, into my hands. Ignoring the evaluation team and walking directly to the piano in the corner, I focused all my attention on the children: “Class, most of you know something about baseball, and know that San Francisco has a baseball team called the Giants. Well, the Giants are in the playoffs to find the best team, to win the championship. There’s a new song about the Giants called “Bye-Bye Baby,” you may have heard it on the radio. Who knows what “bye-bye baby” means?” The children hesitated, unsure of what to do; this was not their usual music lesson. Franklin timidly half-raised a hand. “It means to hit a baseball so hard that the ball goes over the wall, and the other team can’t catch it, and your team scores.” “Yes!” Thank God for Franklin. “Now, imagine we’re all at a baseball game together, this whole fifth grade class is sitting together in a huge stadium full of people. It’s a beautiful sunny Saturday afternoon, somewhere there’s an organ playing. We’ve got hot dogs for lunch, peanuts for a snack. We’re wearing black baseball caps with orange initials ‘SF’ in front, we’re cheering for our team, and our singing is going to help the Giants hit those baseballs over the wall!” I lifted the piano lid, and standing, played the tune. “Listen to the melody, remember how it sounds, and we’ll sing it together. It’s easy!” When the Giants come to town, it’s bye, bye baby! Line by line, I played and then together we sang those simple verses, haltingly at first, then confidently, then with real team spirit. Every time the chips are down, it’s bye, bye baby! I called out: “Now the boys!” They sang. “Girls only.” History’s in the making at Candlestick Park! Cheer for the batter, and light the spark! I pointed to one row, then another. “Row 5… row 3… Odd rows only… even rows only…. Now, I’m going to trick you.” I switched rows back and forth, in the middle of a line, in the middle of a word. If you’re a fan of Giants baseball, sing bye, bye baby! All eyes were attentive, sparkling, eager, and glued to me; we were on a roll! “Boys again.... Girls now... Handsome boys only....” That stopped them—but just for a second. Laughing, the boys sang the next line together. If you want to be in first place, call bye, bye baby! The girls waited eagerly, giggling in anticipation. “Pretty girls only!” More giggles; all the girls sang. “Smart students only…” But they were ready for anything now; they all sang out. “Dumb stu… ah no,” I pretended to stop myself, “I’m sorry, I forgot, there are no dumb students in this fifth grade!” And the whole class cheered! Listen to the broadcast on KSFO, Turn up the volume, and hear them go! “Children with black hair!” I called. All but one sang. “Children with blond hair!” I held my breath, but yeah, Marcella! Her sweet, clear voice rang out. I felt so proud of her. “Girls with two ears… Boys with three ears… what, no boy here has three ears? You’re sure?” More laughter. “Everyone together now!” With the San Francisco Giants, it’s bye, bye baby! Loud, soft, and in between, the children’s voices answered my raised or lowered hand as if following a conductor. A quick glance at the clock showed just enough time to close the music class with a rousing version of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” our voices at full power, our song rattling the walls, windows and cobwebs of old Spring Valley School. We were the Kingston Trio, we were the Shirelles, we were Peter, Paul and Mary! With perfect timing, our song ended just as the bell rang; the children spontaneously clapped and cheered. “Class dismissed.” Cries of “That was fun… That was really great…” floated in the air as the children filed out, still laughing. I felt wonderful, elated, the pain in my stomach gone. Only then did I remember the evaluation team at the back of the room. Words of praise came pouring out from Mrs. Mitchell and the two other evaluators. “That was excellent! That was so well done. You did a wonderful job, congratulations!” The three shook my hand, then departed, following the children down the hall. I closed the piano lid. But where was Mrs. Butler? Had she slipped out, unnoticed, had they left her behind? I glanced around the room; Mrs. Butler, her back to me, was at her desk, gathering her things, preparing to go home. It all comes down to this... I focused on her, my glance turning into a stare, my stare into a contest of wills. You lost, you failed. Now you're going to look at me, I’m going to make you look at me, you're going to look me in the eyes. Mrs. Butler turned to face me with that same icy, stone-cold look of contempt as the day we first met. We silently stared at each other for what seemed interminable seconds, her look of contempt turning into one of pure hatred. I almost laughed aloud. I’m visible, we’re all visible now, deal with it, deal with us. I can look at you forever, I’ve had practice, you lost, you failed, you’re nothing but a bigger, older, meaner, playground bully. Mrs. Butler dropped her eyes, turned, and left the classroom without a word. She never spoke to me again, never looked at me again. *** Just before the end of my last day at school Mrs. Mitchell called me into her office. Once more she congratulated me on my presentation, and on my outstanding evaluation. “I would like very much for you to work here at Spring Valley. I’m sure you would do an excellent job for us.” She paused. “I’m offering you a job, Mrs. Delgado.” At that moment time stopped, something within me shattered, split in multiple pieces. Thoughts, memories, decisions, conversations—all recurred simultaneously in my head. Part of me remembered the feeling of being poisoned, the gnawing ball of pain in my stomach growing larger daily, all the unrecompensed extra hours I had spent in playground duty, being used, lied to, gossiped about, going hungry for lack of time to eat. All were minor issues, really, in comparison to the multitude of random wrongs and injustices suffered by so many teachers, and students, who deserved better. Part of me wanted to boast, to brag to Mrs. Mitchell that the entire presentation had been spontaneous, unplanned. It was extremely gratifying to imagine Mrs. Butler, in spite of all her efforts at sabotage, squirming when reminded of my success. But that lesson plan had not come from me, it was a gift from Budai. To claim otherwise would have been hubris, and another lie. But who would understand these reactions, who could I have spoken with? Immediately I knew the answer to my own question; my peers, my companions, the other Latina underclassmen, they would listen, they would understand. Another part of me had come to a surprise spontaneous decision about the job. From a far-off place I heard my myself answer: “Thank you so much, Mrs. Mitchell, it’s an honor to be offered a job at Spring Valley. I’ve enjoyed being with the children and have come to love them. But I’m sorry, I can’t accept your offer, it wouldn’t be good or healthy for me to work here. But I appreciate it very much; your offer means so much to me.” Platitudes, all platitudes. I didn’t trust her, didn't want to work there, and wasn’t about to tell her the truth—except for loving the children—that was true. Then I waited, whole again, no longer in pieces, curious to hear what she would reply; but after all these years, I no longer remember the rest of our conversation. When I returned to the classroom, it was empty; the school day was over, Mrs. Butler and the students had gone, my chance to say goodbye to the children was gone. I suddenly felt unsteady, emotionally drained, hollow. Something important, something of great value had ended, gone out of my life forever. Looking around the classroom for the last time, I gathered my things for home. But the room wasn’t empty; there sat Budai, still on duty. Rubbing his belly, I bid him goodbye, asked him to continue to protect the fifth graders…. No! That wasn’t good enough, he deserved much more. I tried again. Palms pressed together, respectfully bowing my head, I formally thanked Budai for the lesson plan, gave him credit for my success, and told him that now, with my credential secured, I would look for a job elsewhere. Then I just stood there, waiting for …something… I didn’t know what. Out of a long silence broken only by the steady ticking of the classroom clock, once again I heard Mrs. Butler’s words: “It was a ‘welcome to our school’ gift given to me by the Chinese parents when I first started teaching at Spring Valley.” Budai was smiling ...our school.... Oh, I’m so slow sometimes, it can take me ages to figure things out. Clever, clever people, those parents. And subtle. They had known exactly what they were doing. Budai, disguised as a gift that could not easily be disposed of, would be a welcome resident in the classroom of a loving teacher, a thorn in the side of any other. Welcome or unwelcome, he would be there, doing his job. Budai was laughing. Again, I heard the class tell me: “He’s the Laughing God who protects all his children and gives them what they need.” …All his children… In my narrow mindedness I had been thinking only of the young students in the class; but hadn’t I, for a short while, been part of this fifth grade? He had always been there helping me. For I too was Budai’s child. … but then, so was Mrs. Butler. Budai, the Master Teacher, had provided us all with what we needed.  Gloria (Calvillo) Delgado, born and raised in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district, is the daughter of a Mexican father and a Hawaii-born Puerto Rican mother. She and her late husband David lived for many years in Albany, California, where they raised their family. One of her stories, “Savanna,” was included in the Berkeley Community Memoir Project's recently published collection, “A Wiggle and a Prayer.” She has had four stories printed in Somos en escrito, including “El Parbulito,” a first-place winner in Somos en escrito’s 2019 Extra Fiction Contest and included in El Porvenir, ¡Ya! - Citlalzazanilli Mexicatl - Chicano Science Fiction Anthology. Recently widowed, she now resides with family in a rural community outside Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she has resumed writing.

0 Comments

“Piano”by Linda Zamora Lucero Papa’s funeral, spring 2009. In the tiny chapel are my sister Ellie and her clan from Phoenix, my brother Tito, both of Tito’s ex-wives, and Papa’s best buddies—Montez leaning on his cane, Garcia in his wheelchair, reeking of cigar—both retired welders from Hunters Point shipyard. Papa radiated so much love even my newly ex-boyfriend Julián shows his face to pay final respects. Only Mama is missing. When Tito went to pick her up, she insisted she was too distraught to come. Great, I think, although I don’t believe it for a second. Sure enough, just as the service begins, she materializes in the middle of “Gracias a la vida” in a red coat and yellow hat with feathers. “I don’t need help to sit down!” Mama says, slapping the usher’s hand away. “You’re late,” I whisper, grudgingly making room for her in the pew. Dressed up for Papa, I’m wearing a fitted black dress with tiny hand-sewn turquoise flowers, a Oaxacan shawl, large hammered gold hoops, black hair pinned up. “Hello, Raquel,” Mama says pleasantly, sitting on the fringe of my shawl. “Such beautiful music.” And she commences to hum along with the vocalist. Yanking the shawl loose, I close my eyes and pretend she isn’t there. **** After the service, our family gathers at Tito’s house, where we wolf down plates of homemade chile verde, throw back shots of Herradura and recount the same cherished stories we always do whenever we get together. A favorite is how one Thanksgiving—this was before Mama abandoned us—we children were squabbling over the drumsticks—and Papa asked if he could just this once have some peace around the table. Seven-year-old Tito, thinking he was being real hilarious, smugly handed Papa the bowl of peas, whereupon Papa angrily slammed his fork on the table. We watched in horror as the fork slowly became airborne and cracked the kitchen window. We ate in chilly silence until the pumpkin pie with whipped cream made us boisterously happy again. Tito says, “’Member?” We laugh at the timeworn anecdotes, fall silent with grief. At the ripe age of thirty-nine, Ellie gets up to dance, leading us in a raucous chorus of “Papa Was a Rolling Stone.” Missing Papa’s delighted belly laugh at his youngest daughter’s antics, I suppress a shuddering sob. Ellie’s kids bickering over a toy feels like the saddest thing in the world. Tito brings Mama a cup of té manzanilla and fusses over her. She eyes the proceedings from a corner armchair, the feathered hat like some ridiculous canary atop her head. She’s on her best behavior. Of course, it doesn’t last. Barely three weeks pass before the director of the Thirtieth Street Senior Center calls me at Galería Libertad, the community art center I direct, asking to meet with Mama’s family, meaning Tito and me, since Ellie is safely back in Phoenix. Thirtieth Street is where Mama eats lunch on weekdays, takes piano classes, and is an active member of Mr. Topper’s Mission Tappers, no tapper under seventy-five. Before he died, Papa spent his Saturdays playing poker at Thirtieth Street. “I realize this is a difficult time, so I do apologize,” Mrs. Whitmark says, her lipstick pomegranate pink. She pauses, looks up through bifocals, and an all too familiar despair washes over me. To most people, Mama is an eccentric elder with a mind of her own. Some of us know otherwise. “Mrs. Flores is accusing people of stealing from her purse. Everyone is suspect—the other seniors, the janitors, the cooks, even myself. It’s quite upsetting. Your father helped calm her whenever she got this way, and now we need her family to step in.” “Of course,” Tito says, nodding. “We’ll talk with her.” Tito is a machinist for the transit system. He’s completely overbearing, but somehow women find him fascinating. He’s been married twice with no children, while I can’t seem to find my match, romantically-speaking. Tito has no idea what I do at Galería Libertad. He teases me by introducing me to his friends as “my sister, the starving artist,” and he’s not far wrong. But in the Mission arts community, I have found friendship, love, sustenance. My home. “Losing Dad hasn’t been easy for Mom,” Tito continues. I love my brother, but when it comes to Mama, he ticks me off. “She’s crazy,” I say flatly, brushing a strand of hair from my eye. After Papa’s funeral I’d shorn my long hair into an asymmetrical what-I-hoped-was-stylish cut. Tito shoots me a foul look. But crazy explained my mother who, one ordinary morning after Papa had gone to work, made us children breakfast and sent us off to school, then took a train back to her hometown in New Mexico. To stay. Tito was ten; Ellie, six. I was twelve. In the chaos that followed we all pitched in to help Papa with shopping, cooking and housekeeping. That was the easy part. After Mama left, Ellie suffered from debilitating headaches and Tito was suspended from school every other week for one thing or another. Papa began drinking heavily. There was no one to turn to. My parents had grown up in New Mexico, but we were born and raised in San Francisco in four rooms on Shotwell Street, miles away from kinfolk who gossiped about the neighbors, shushed children at weddings and offered solace when worlds shattered. I was raw with anger at Mama, praying that she’d return to us, declaring that she wouldn’t dare. “Maybe,” my best friend Anna said, “she ran off with a lover.” Prone to dramatic flights of fancy, Anna with her black cat’s-eye glasses concocted wildly romantic stories about our favorite middle school teachers. Now she had one for my mother. Maybe you can just shut up,” I said. A weak response, but heartfelt. Crazy explained Mama’s sudden reappearance in San Francisco five years later. That was the first time a social worker told us Mama was “mentally and emotionally unstable.” But I knew he meant crazy, and for that I was grateful. It explained her crying jags, her periodic paranoia, her denials that she needed help, her refusal to take prescribed medication. Crazy summed it up. In Mrs. Whitmark’s office, Tito loudly clears his throat and promises that he will get Mama to take her meds. “Good luck,” I say, grabbing my daypack. Tito is uncharacteristically silent as we leave Thirtieth Street, his broad, good-natured face splotchy. As soon as we reach my beat-up Toyota, he lets loose. “You were out of line, Rocky, calling Mom crazy! She’s our mother!” Tito and Mama wrote each other regularly after she left. She worked in a café near Taos, and, as we found out later, had reconnected with a high school flame. I was horrified. Tito and Ellie visited her summers, but I refused. When Mama returned, my siblings were elated, being younger and obviously needier than I was. In the five years she’d been gone, I had become 100% Papa’s girl, Athena sprung from Zeus’s head, full grown and battle-ready. Papa never dissed her, but I held her responsible for his alcoholism, his melancholy, for all of us having had to answer endless questions from teachers, busybody neighbors, and shitty strangers who felt sorry for us. Because what’s more pitiful than motherless children in a strange land? So when Tito says, “She’s our mother,” I say, “You’re entitled to your opinion, Tito. I have to go. We have an exhibit of Cuban posters opening in a week.” “Weird haircut,” he snorts. He gets into his car and peels out, as if he were sixteen instead of forty-one. I burst out laughing as his Midnight Blue Chevy leaves fat skid marks on the asphalt. The next time I see Tito, I’ll ask about his prize roses. We Flores don’t say Sorry, even when it’s called for, or a straight-out up-front I love you, even though we do. After an argument, when one of us asks about the weather, it means I’m over it. Dancing salsa after a backyard barbeque means I love my family, or I love the whole fucking world and everything in it. Things go unsaid for days, even years, the love, anger or sorrow pent up inside like a great accumulation of molten lava below surface, wanting release. It’s the Flores way. Friday evening, I’m at home on the computer, writing wall text for the exhibit, half listening to Jeopardy. The category is “Shakespeare,” the answer is “Doubtful Dane.” My cell buzzes—Ellie in Phoenix. I ignore it. We used to watch Jeopardy, Papa and me. He admired Alex Trebek. Debonaire, brainy and not above showing it. A contestant hits her buzzer and shouts “Who is Hamlet?” On Ellie’s third call, I answer, muting the TV. “Mom’s not answering her phone,” my sister says. “I wasn’t answering my phone either,” I chuckle. Ellie ignores me. “Mom was perfectly fine yesterday—Tito says she’s taking her meds, but now I’m worried.” Usually, Ellie asks about what’s happening at the Galería, or about my mostly pathetic, sometimes hilarious dating forays in the six months since I broke up with Julián. Not this time. “Have you seen Mom since the funeral?” On television, Alex Trebek’s lips announce Final Jeopardy, inspiring looks of consternation in the contestants. The category is “San Antonio, Texas.” “Remember the Alamo?” I ask Ellie, wishing she didn’t live so far away. I miss our sisterly heart-to-hearts over her homemade biscochitos and wine. “Come on, Rocky, would you just get over there and check on how she’s doing? Tito’s in L.A. this week.” I sigh loudly, meaning yes. “Great! Love you!” she says, and hangs up. And the burden shifts to me. Mama lives in the same paint-peeling, rent-controlled Edwardian flat we were raised in, located in the heart of the Mission—what the realtors gleefully call “a neighborhood in transition.” No doubt. Since 1492. The door cracks open. “Hi.” I slide my foot inside before Mama can decide whether or not she wants a visitor. “It's me, your daughter.” “I know.” Hazel eyes peer up at me through huge red eyeglass frames. Mama is queen of her private little planet. She’s wearing a crimson apron with gold rickrack trim over a blue sweater shot with silver on top of a fuchsia dress. Purple leggings, lambswool slippers and a silver “Hottie” pendant complete the look. We are nothing alike. Born in the history-rich Abiquiú, New Mexico, Mama grew up speaking Spanish but she looks like a gringa with pale skin, auburn hair, light eyes like a wary cat. I’m dark like Papa, and proud of it. His first language was also Spanish, but his maternal grandparents were Taos Pueblo. I dress in black: turtleneck, jeans, boots. I do rock the earrings, however; the showier, the better. Today’s earrings are humongous crimson Lucite hearts, a gift from a Oaxacan artist. “What happened to your hair?” Mama says. “Why don’t you answer your phone?” I counter. The flat smells of Papa’s Tiger Balm and tobacco. I have to stop and catch my breath. “What’s wrong with you, fighting with me already?” Mama looks down the street before closing the door. “I thought you were someone else.” Her tone sweetens. “How are you, anyway, Raquel?” An ordinary question in an affectionately maternal voice, perfectly calculated to derail me. She does this every so often, and when she does, my heart flips like a kite in high wind, and I wonder what it would be like to have a real mother. Would we go to museums together? Would we shop for shoes, get our nails done? What do regular mothers and daughters do? The question slams into me whenever I run into girlfriends with moms, enjoying themselves. Mama hadn’t been there to help me buy my first bra or see me win first prize in a high school art contest. There was more I’d missed, things more profound. I just didn’t know what. The hallway is piled with boxes. “What’s this?” I ask. “I called Goodwill, but they’ve gotten choosy…your father kept everything: clothes, magazines, rusty tools.” A wave of fear hits me. “Goodwill? Where’s his brown suitcase?” Blood thunders in my ears. I catch a glimpse of myself in the hallway mirror. I look exactly the way I feel, bug-eyed and off-kilter. “There’s more in the garage. Not interested in old junk. Old junk, old men, old ideas.” Mama laughs, apparently delighted with herself. Old junk? “Please, please, don’t give anything away! I’ll get Tito to bring his pickup next weekend and we’ll take it all.” She disappears into the front room where the furniture—sofa, coffee table, Papa’s La-Z-Boy—has been moved against the walls. She pulls aside the lace curtains on the bay windows and looks out to the quiet street. “The piano should be here by now.” “Piano?” She doesn’t need a piano. Tito gave her an electric keyboard on one of her birthdays. It’s programmable, so that she can play tango, classical or her pop favorites. Papa would read his detective novels in his recliner, foot tapping while she plinked out Beatles tunes note by note. I never understood why he took her back. “Respect your mama,” Papa admonished me when I gave her attitude. “No matter what, she is your mother.” Respecting Papa, I shrugged. I was seventeen when she returned to Shotwell Street, my eyes were already focused on college and the wider world. Turning from the window, Mama says, “Can I borrow ten dollars until Friday?” I dig into my bag and hand her a ten and a twenty. “Just keep it.” I feel vaguely virtuous, giving her something without begrudging it. “I said borrow, Raquel, and only ten until Friday when my social security arrives.” The folded bill disappears into her apron pocket. “Whatever. I’ll have some water and then I’m out of here.” Running the faucet in the kitchen, I check for signs to report to Ellie. Cereal bowl in sink, oatmeal encrusted. Golden moth orchids I’d bought for Papa at the Alemany Farmer’s Market, shriveled and fallen onto the windowsill like exploded firecrackers. Portrait of the recently-elected President Obama. Wall calendar from La Palma Mexicatessen, inked Xs marking the days. Today is April 6. No X as yet. Mama is right on my tail. “I pay my debts. I’m not like that Julián of yours. He still owes me money.” Here we go. “Jeeze. It was change for a parking meter.” I feel my temperature rise. “I’ll repay you! And you can forget Julián because Julián and I are not together!” Papa’s eyes got cloudy as he aged, but not Mama’s. Her eyes are like new-minted dimes, bright with gotcha. “I don’t forget. Julián shouldn’t be borrowing from old ladies. I’m glad you’re rid of him. It’s better to be alone, Raquel. You’re smart, like me. The smartest of my children.” I’m floored. Mama has never expressed the slightest interest in my life or anyone else’s for that matter. Although mortified by the comparison, I can’t help being flattered that she considers me the smartest. “So,” I say, softening. “You’re renting a piano?” Her arms fold defensively. “It was on sale.” “You bought a piano?” Baffled, I pull out a chair and sit at the kitchen table. “For my music lessons, Raquel.” Still standing, she bristles with nervous energy, her pendant flipped so that it reads “eittoH”. “What about the keyboard Tito got you?” “I need a real piano. Besides, Tito steals from me.” Yup. Genial to eccentric to crazy at maximum velocity. The woman who brought me into this world is fundamentally incapable of being the mother I long for. I know this in my heart, in my brain, in my gut, in my very pores, and yet she gets me every time. I rise to tighten the dripping faucet, then turn to face her. “Look, Tito’s here every weekend, and when he can’t, he calls to see how you’re doing,” I say, defending my brother. “Why do you give him such a hard time?” A better question is why am I trying to reason with her? “You know damned well I can’t trust him.” I take slow, deep yoga breaths. Do not engage. Do not engage. Mantra for Mama. Outside, a vehicle rumbles to a stop. “It’s here!” she says. I follow as she rushes down to the sidewalk, patting her hair in the mirror on her way out. A deliveryman in a maroon jumpsuit strolls toward us from a double-parked delivery truck. “Piano?” he asks me. He has sleepy eyes, a pencil-thin mustache, a clipboard. “You’re late!” Mama says. “Sorry, ma’am.” He tips his cap back. “I’m Jesse and that’s Murphy.” Murphy is pulling a ramp from the back of the vehicle. Mama ignores Jesse’s proffered hand. “Where does it go?” he asks me. I blink, smiling. “I’m just an innocent bystander.” “Up here,” Mama interjects, leading us up the steps and into the living room. “You ordered a Yamaha grand?” Jesse is finally addressing questions to the right person. “Ma'am, we get a nine-footer in here and you won’t have room to sit down and play.” “There must be a mistake,” I say. “I don’t need much room,” Mama says, shooting me a dark look. “Move, Raquel, you’re in the way.” So be it, I think. I’ve always been in your way, we all have, Papa, Ellie, Tito. You could have continued therapy, taken the pills, and avoided the crises that your family—not that you recognize us as family—have had to rescue you from over the years. Selfish, selfish, selfish. I back myself against the hallway wall as the movers expertly rotate the piano to make the tight turns. Well, I’ve done my duty. My report to Ellie: Mama is alive. Mama is well. Mama is impossible. “I’m coming back this weekend for Papa’s stuff,” I say, “and will you please answer your telephone? Because Ellie and Tito worry about you.” As I take off, I hear Mama telling the deliverymen, “There’s ten dollars for you when you’re done.” **** On Sunday Tito is wearing his annoying “I’m just a regular vato from the barrio” get-up—Ben Davis work pants and his “Stay Brown” t-shirt from the San Jose Flea Market. We’re both wearing Giants caps. The sun is out, there’s a game this afternoon. I’m anxious to get back to the Galería where volunteers are painting the walls. “We’re here for Papa’s things,” I say, when Mama comes to the door. She is channeling Cher today: red tunic, shaggy vest, ankle boots. Gray wisps escape a blue-sequined beret the size of a small pizza. “God, open a window! Aren’t you hot?” “Leave me be, Raquel. You know I’m always freezing,” she says. “I'll make coffee now that you're here, Tito.” My brother is definitely her favorite child. There are times I believe he is the only person in the world who can get through to Mama, but when I really think about it, I shake my head, No. Because after his visits she accuses him of stealing and she cries. Always. “Momskh!” Tito says, draping his beefy arm around her shoulder, “Where’s the pianoskh?” Mama’s eyes light up. Tito has invented this Russian-esque language just for her. “Who told youskh?” she giggles, leading us to the living room. Tito halts theatrically in the doorway, throws his hands up in wide-eyed astonishment, “Whoa! That’s some piano!” The piano is impressive, gleaming ebony, padded leather bench tucked underneath, filling the room like one of those clipper ships crammed inside a tiny glass bottle. “What do you think?” Mama is giddy. “What do I think?” Tito bellows. “What do I think? Takes up a lot of space!” Somehow this is the right answer. Mama practically squeals with pleasure. If there were room she’d be pirouetting around the piano. “It's ridiculous,” I say, addressing Tito. “If she needs a so-called ‘real’ piano, which I doubt, a used upright makes more sense.” Tito’s look tells me to can it. “This is a piano for professionals,” I emphasize, unable to help myself. I’m the director of a community arts center. I believe that everyone has the capacity to make art, to enjoy a creative life. This is my work, yet I can’t manage to extend this value to Mama. I feel like a miserable imposter. “I love it,” Mama says, defiantly. “Play us something, Mom!” Tito doesn’t have to ask twice. Mama climbs onto the bench and sorts through dog-eared sheet music. She begins playing “De Colores” and Tito, leaning over her shoulder to read the lyrics, sings with her. Both are seriously off-key. I escape, taking the kitchen stairs down to the backyard where weeds are suffocating Papa’s tomato plants, and enter the garage from the side door. Underneath the floorboards, the caterwauling is mercifully muted. Papa sold his car awhile back, so the garage is now storage space. I wade through boxes and furniture before I find what I’m looking for: Papa’s brown leather suitcase. Wrenching it free, I wipe the cobwebs with an old t-shirt and sit cross-legged on a box, my heart at peace. The tarnished metal fasteners make a satisfying pop. Lifting the lid, the faintest scent of tobacco in the yellow silk lining sweeps me back to another time. It must have been fall. The living room windows were dripping condensation. Mama had been gone a year. I was still crying myself to sleep. Papa set the suitcase on the coffee table. “Let’s see what we have here,” he said, a cigarette in one hand, a can of beer nearby. His hair was still coal-black, but he was starting to get a paunch. He’d drag out the suitcase now and then, often during the holidays, to show us his treasures—a jumble of photographs and souvenirs—a pretext for his stories of back home. That day it was only me sitting by his side on the worn sofa. I reached for a sepia-tone studio portrait of an elegant native woman in a 1940s fur coat. “Who’s this?” I knew the story by heart, but I never tired of his stories of wicked uncles and chain-smoking grandmas, homesteads and adobes, farmers and dressmakers, sheepherders and coal miners, pueblos and penitentes, trains, abductions, adoptions, fires: tales of love, tragedy and survival reaching back across generations to New Mexico Territory and beyond. “My first cousin Josie, on my mother’s side. She had a tailoring shop in Santa Fe. She was a sharp cookie, married and widowed three times, the last husband a Navajo. She liked them young but it didn’t matter. They still died on her.” We chuckled. I pulled up an unfamiliar snapshot of a couple picnicking on a blanket at Ocean Beach, the Cliff House in the hazy distance. “And this one?” A shadow crossed Papa’s face. With a sinking heart I recognized my youthful parents in a happier time. Silence flooded the room. Papa’s thoughts seemed to alight on something not in the picture, the ashes on his cigarette trembled. Finally, he smiled, seemingly chagrined by his thoughts. I switched the photo for one of Papa as a boy and his older sister posing in front of a Ferris wheel. “I wished I’d known Auntie Rose,” I said. Papa never returned to New Mexico after he and Mama moved to San Francisco—his immediate relatives had moved away or died by then. If there were other reasons, he never shared them. “You remind me of Rose, mi’ja,” he said. “Sparky as hell.” Besides photos, there is a ledger of the early 1900s written in Spanish and English, discharge papers, faded postcards from distant relations we children never knew, yellowed newspaper obits, a ruby ring won in a poker game, a ring neither ruby nor gold. This is what I came to rescue from Goodwill. My father’s life in a suitcase—all we have left of him besides his stories etched into our memories, tales that kept our family tethered to our history, to this land, to each other. I secure the suitcase, one snap at a time, and haul it up the back stairs to the living room where Tito and Mama are hammering out “That’s Amore.” Tito insists on getting burritos and a six-pack for lunch. We dine on the kitchen table of our childhood, while Tito tells us about his new lady friend, a teacher. Mama tracks his every word, the better to throw in his face one day. Tito is oblivious. Someone in the building has the game on, radio turned full blast. “The bases are loaded with two men out! Herrrrrre’s the pitch!” When we were kids, listening to the Giants with Papa was the best. Halting in the midst of whatever we were doing—peeling potatoes or washing the car—to visualize the players at the ballpark, we held our breaths, waiting to hear Jon Miller yell, “The ball is up, up…it’s out of here!” My spirits lift remembering how we’d yell and high five each other. Then the heaviness in my chest returns. I claim the suitcase when it’s time to go. The rest of Papa’s things will go into Tito’s garage until Ellie can come out to help sort it all. On the sidewalk, Tito stretches and grins. “Mom’s doing okay,” he says. “We’ll just have to check in on her more often.” “Do you know what a piano like that costs?” Tito’s smile vanishes. “Don’t worry about it, Rocky, I got it covered.” “She can’t wait to get rid of his stuff.” “You can’t know how anybody feels except for your own damn self.” Tito’s voice is hard. “Mom does the best she can. You’re past forty. Is this who you want to be? We grew up with her too. And what’s with that haircut?” Glaring at my brother, I slam the trunk lid closed and get into my car. Wiping away tears, I turn onto Valencia Street, glad to be heading to the Galería. Three signal lights later, I realize I’ve forgotten my Giants cap and make a U-turn in the middle of the street. On Bartlett I drive by two little girls playing hopscotch on the chalked sidewalk like Ellie and I used to do, and pull up in front of the Lermas’ building that has a For Sale sign. Sal is sitting on the stoop, drinking beer and listening to oldies on KPOO. “Hey Rocky. Sorry about your father,” Sal says, as I exit the car. “We lost a good man.” “Thank you.” I’ve known the Lermas since forever and wonder whether they’ve found a place to move to. Before I can ask, I’m distracted by the faint sound of music coming from Mama’s flat. I climb her stairs and peer through the open bay window, past the lace curtains, where she sits half-hidden behind the big, lacquered instrument. Her fingers strike the keys as she squints through her enormous, red-framed glasses at the sheet music, her voice tentative. “Sweet dreams till sunbeams find you…” The playing is measured and precise. The voice not so much, even as it picks up tempo and exuberance. “Sweet dreams that leave all worries far behind you…” I take a breath as my heart unexpectedly catches on a surging memory of Mama sitting on my bed when I was a girl, singing me to sleep. Cozy in pajamas, bed covers pulled up to my chin, lulled by her voice, drowsy. Back when she was still my Mama. “And in your dreams, whatever they be…” Mama warbles with joyful enthusiasm. The afternoon’s heat has eased. Rising above the ambient sounds of the street—a plane overhead, a skateboarder rolling past—is my mother’s voice falling in and out of tune like a kid learning to ride a two-wheeler. Mama in her blue-sequined beret is swaying, creased fingers moving over the black and white keys of the piano, focused on the task, determined like all of us to catch beauty in this precarious life. The sound of the music awakens a raw tenderness in me, if only for the moment. Brushing unexpected tears from my eyes, I sink onto Mama’s front steps to listen.  Linda Zamora Lucero is writing a collection of short stories set in San Francisco’s multicultural Mission District where she was born and raised. She identifies as Chicana, and attended Mission High School, City College of San Francisco and SFSU. Her published short stories are: “ZigZag,” LatineLit Magazine, 2022; “Speak to Me of Love,” first prize winner, DeMarinis Short Story Contest, Cutthroat: A Journal of the Arts, 2021; “When It Rains,” Yellow Medicine Review, 2020 Pushcart nominee; “Mexican Hat,” Puro Chicanx Writers of the 21st Century 2020 Anthology; “Balmy Alley Forever,” Yellow Medicine Review, 2016; and “Take the Money and Run–1968,” Bilingual Review, 2015. Lucero's day job is directing the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival, an admission-free outdoor performing arts series in San Francisco. Click here for Part 1. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed