Memories of a Mexican Boy Growing Up in El Paso: Cuca, Babe, Louie, and Dannyby Daniel Acosta, Jr. Prologue I grew up calling my grandmother—Cuca-- and my aunt--Babe--by their first names; I don't know why but Louie (Babe’s son) and I always did. Babe was my mother's younger sister and Cuca was their mother. Babe, Cuca, and my mother were very close. They seemed like sisters. Louie was named after our grandfather, Luís. Louie was five years older than me and was the one who taught me about life. My maternal grandparents did not have any sons; Louie and I were the boys in the family. A good part of my early childhood was split between my parents' run-down rental home and Cuca's house, which seemed like a palace to me because it had a bathroom with a tub. My parent's home finally got a stand-up shower when I started first grade because there was not enough room for a tub with a shower. When I started first grade in the fall of 1951and until I completed the 4th grade, I remember spending many days and nights with Babe, Louie, and Cuca. Papa Luís had died when I was very young, and I do not remember him. Cuca’s House I really liked staying over at Cuca's house on Piedras Street. From her front door we could see the dirt-brown Franklin Mountains looming in the distance. Her house had a small front yard with a white picket fence and vines growing on the enclosed screen of the front porch. There was an unpaved driveway to park the car and further down the driveway was a detached garage, which was used mainly for storage of old furniture. Next to the garage was a wobbly gate that led to a tiny backyard with a peach tree and some scrubby bushes. The backyard was mostly dirt with a few, scattered patches of grass. The house next to hers had a large backyard; a rickety wooden fence separated Cuca's house from the neighbor's yard. Over the fence I could see my parents' rental home on Hamilton Street, which was essentially two houses away if I wanted to take a shortcut by jumping over two fences. Instead, I ran up the rocky alley between Hamilton and Idalia, which dead-ended on Piedras. One could enter the house from the back by entering a half-door that that connected the unfinished part of the basement to another area with a locked door that was finished into a bedroom for Babe. Outside of Babe's bedroom door was a small area where an old-time washer was located. It had a wringer attached to the washer and once the clothes were washed, they were placed through the wringer and were wrung dry by physically rotating the handle of the wringer. The clothes were sun-dried in the backyard on a small clothesline. Right above the washer was a small basement window just small enough for a small boy like me to squeeze through, which I did a couple of times to get into the house. The other way to get into the house through the back was to walk up some shaky wooden steps to a door that opened into a small breakfast room and then to the kitchen. At the top of the stairway was a small landing with a window on the side of the house where Cuca's bedroom could be seen. Next to the breakfast room, off from the kitchen, was the bathroom, directly opposite Cuca's bedroom. Leaving the kitchen there was an area I guess one would call the formal dining room, which had a dark mahogany table with six matching chairs. From the dining area there was an arched opening which immediately became the living room, where there was an upright piano under the north window and a sofa next to the piano. Later when I was older a large black and white television was purchased by Babe and Cuca. We spent many nights watching professional wrestling and boxing matches. I learned to recognize many of the fighters from Babe and one of my favorites was Sugar Ray Robinson. We would keep the front door opened so a nice breeze from the west came through the screened front porch into the living room. One could reach Babe's basement bedroom by going down a very narrow staircase which came off from the dining room. During the winter months, Louie and I often slept together on the sofa in the living room; a large gas heater was in the dining area which was turned on in the early morning by Cuca so Louie and I could get warm before we had breakfast. During the warmer months we slept downstairs with Babe in her large queen-size bed. In the summer the basement was always much cooler than the rest of the house, and I liked the dampness and darkness of the basement, where I could read my comic books under a small lamp. Babe and Louie What I remember most about Babe is the way she treated me, as if I were much older. Babe, Louie, and I often watched the soap operas on TV during the summer months, and she would explain things to us about why so and so was divorcing her husband and who was stealing money from the company. We all laughed when Babe got it right and gasped in horror when someone was killed in an accident without any warning. When there was time in between the shows, I jumped up from the couch and ran down Piedras to Beacon’s grocery store to get her favorite drink--not the stubby Coke bottle but the long, thin Pepsi which was sold cold. I also remember watching "A Tale of Two Cities" with Babe, and when the novel was required for my ninth-grade English class, I already had a good idea of the plot. Through Babe and TV, I learned much about how white people lived in America. I instinctively knew that we were different from the Anglos, but it was Babe who taught me to be proud of my Mexican heritage. With Louie’s guidance, I learned to play all the sports, especially baseball. I was able to play with boys 4 or 5 years older than me and picked up many tricks on how to become a skilled ballplayer. I became interested in organized Little League and Pony League baseball, playing first string as a centerfielder and shortstop for two different teams. Babe, Louie, and her long-time boyfriend, Johnny, were the only ones in my family who saw me play baseball during the summer months. Cuca called Johnny El Árabe; there was a large contingency of Lebanese families (but not really Arabians) living in El Paso. I was not much of a hitter, but I played first string because I was the best defensive outfielder and shortstop on the team and made several outstanding plays each game. They would be in the stands each night rooting for me. After the games, we often walked down Piedras to eat out at two greasy spoons which were near Beacon's. There were two bars directly opposite each other on Piedras—Jimmy's and Pike's--and both had small kitchens. When we were in the mood for good tacos we ate at Pike's Bar and when we wanted great hamburgers we ate at Jimmy's. We leisurely ate and listened to songs on the juke box that the bar customers had selected. Babe and the Authorities One summer Babe decided to paint the interior of the house and she said let's go, Danny, and get some paint on Paisano Street, the supposedly dividing line between the Mexican and Anglo neighborhoods in El Paso. Cuca's house was in Manhattan Heights where there were mixed neighborhoods of whites and Chicanos. We got into her old 1950-something Ford Fairlane and took off. Along the way she pointed out the differences in the neighborhoods and the types of people. We both laughed when we saw a man turning left using both his blinking turn signal and sticking his arm straight out with fingers extended; Babe said he wanted us to know where he was really going. On the way to the paint store, we were pulled over by a cop for not coming to a complete stop at an intersection. Babe was very polite and smiled nicely at the policeman, who eventually gave her only a warning ticket. Babe told me that it pays to be always friendly! When my cousin Louie and I were both going to Rusk Elementary School in El Paso during the 1950s, I remember seeing Babe talking fast and excitedly about her son, Louie, to the principal and some teachers after school. He had been reprimanded for speaking Spanish on school grounds during recess; it was a school rule that only English could be spoken at school. It is a cliche to say now that Babe was a woman before her time. I only wished I could have heard her take down the authorities for what they did to Louie. A few days later she told me what happened, and broadly smiled that Louie would have no demerits on his school record. One night, when all three of us were sleeping in the basement bedroom of Cuca's house, I heard someone jump over the back gate and look through the bedroom window next to the gate entrance. I nudged Babe and told her that I saw a man outside. She jumped out of bed and took Louie and me to Cuca's back bedroom upstairs. We sat on her bed while Babe called the police and made sure the doors were all locked. It was fortunate that were two locked doors in the basement which made it difficult for the intruder to get into Babe’s bedroom. However, while Babe and Cuca were in the front of the house, Louie and I heard steps on the back stairs. When he reached the back door, we saw his profile against the moon light through the thin curtain of the window. He banged on the back door to make it open but was unsuccessful. He then ran down the steps because police sirens were now getting louder. We heard him yell when he slipped and fell. It was on that same bed that Cuca would often tell us stories of her life and family in Mexico. We learned from her that David Siqueiros, the famous Mexican muralist, was a distant relative. She smiled wickedly that he was a Comunista! The last thing I remembered seeing was Babe in the living room calmly talking to the police about the intruder, who had fled the scene. A few years later Louie told me that the intruder had recently been paroled from prison and made the mistake to try to break into Cuca's house. He had to go to jail again when he was caught by the police. I also learned much later in life that he was Babe's former boyfriend. When I was in my fourth-grade class later that same year, our teacher, Mrs. Shlanta, gave an in-class assignment to write a personal story about our family, all within an hour of class time. I thought quickly and decided to write about the intruder. I titled the story, "The Burglar", to make it more interesting and which I could write about without much difficulty in one hour. I left out the part of seeing the intruder a second time on the back stairs. She was very impressed and asked if I was scared. No, I said. It was because Aunt Babe knew exactly what to do to keep the burglar out of the house. Louie and I were really scared to see the intruder so close to us and to hear the banging on the door. I guess we were so lucky that he did not get in. But I couldn't tell Mrs. Shlanta that. I was given an A for the story. Louie and Danny Two years later our family had moved to another rental house, still on Hamilton Street, directly across from our first house. Louie was now in high school and was driving a cool, light green Studebaker. I did not spend as much time at Cuca's house as I used to, but I still went over to see Babe and Cuca after school. Having a car and being a teenager, I did not see Louie as often. But one evening around 10 PM my mother and I heard Louie knocking at our front door. He was out of breath, and he told us that a Mexican gang from Chivas Town (several blocks west of Piedras near Alabama Street) was chasing after him. He had left his car up the block on the corner of Piedras and Hamilton, next to Mr. Wicks' house. We called Babe and she said for Louie to sneak over to the back yard, just a few houses from ours. She would be waiting for him at the small basement half-door. About an hour later, we heard police sirens and saw police cars parked near Mr. Wicks' side lawn. My mother and I walked up the street and saw that Louie's old Studebaker front windshield had been completely smashed in with rocks and bricks. Again, I saw Babe calmly talking to the police and asking them what would have happened to Louie if he had been in the car? Louie was not at fault; the police had to go after the gang members. That was my Tía Babe. The only gangs near my neighborhood were Mexican. There were two Mexican gangs who fought mainly among themselves over territory and if you did not belong to either gang, you had to be careful about showing any preference for one gang over the other. There were no white gangs at my school, and I never saw any whites trying to beat up Mexicans in my neighborhood. Louie taught me to avoid any interactions with the Mexican gangs, unlike his run-ins with some of the gang members. Seeing his front car window completely smashed on that summer night made a deep impression on me. I kept a low profile at school and stayed away from gang members. It didn't hurt that I was known for being an A student, who academically outperformed many Anglos in the classroom. The word in the street was to not hassle Danny. However, there was a time when I had to intercede when some female Mexican gang members were trying to beat up an Anglo girl, who I knew in one of my classes. This incident occurred as I was walking home after school down Piedras about a mile from Cuca's house. Luckily for me none of the male gang members were around and I was able to convince the Mexican girls from hurting the white girl." I was friendly with many of my Mexican classmates, and several of them advised me to not associate with the gringos and to keep my Mexican identity untainted. But I wanted to be accepted by the more popular whites at school. I tried out for the 8th grade football team and started as the first-string end, offensively and defensively, which gave me status with some of the white elites. I began to walk a fine line between my white and Mexican classmates by trying to please both groups. In the end, I had problems with my ability to accept my Mexican heritage and my desire to be part of the elite whites in school. It was later in high school that I became proud of my Mexican background. My deficiency in speaking fluent Spanish, like the rest of my Mexican friends, was beginning to be more difficult to hide from everyone In my 8th grade Spanish class, our Spanish teacher, Mrs. Curry, complimented several of the Mexican students for their excellent pronunciation of Spanish words. Because I was the straight A student in all my classes and recognized openly by many of my teachers, it became noticeable to several of the Anglo students that I was not highlighted for my proficiency in speaking Spanish. An Anglo member of the football team in the class jokingly asked Mrs. Curry about my Spanish abilities. There was dead silence in the class, except for a few giggles. Mrs. Curry quickly started a new topic, and that started my decision to be less sociable with my classmates. Throughout my years at home and school I refused to speak Spanish. I thought by being less Mexican I would be more accepted by my white classmates. Of course, when I spoke in Spanish to my Mexican friends, it was terrible, and I was mocked for trying to be more Anglo. Still, I had some good Mexican friends. Many of my Anglo classmates attended Austin High School and were cordial and somewhat friendly, but I knew my secret was out and that I really did not belong entirely to any one group at school. Epilogue By the time I was three, I had decided on my own to not speak Spanish at home or at school; I thought that I would be more accepted by my white neighborhood friends and classmates and by my teachers. My parents would talk to me in Spanish and English and did not force me to respond in Spanish. Babe never made me feel ashamed when she spoke Spanish to me and did not care if I responded in English. She mainly spoke Spanish with me when she wanted to make an important point about some matter. I learned a lot from Babe: she was a forthright woman, who was proud of her Mexican heritage and spoke out when confronted with discrimination and racism. She had a long and good life, passing away when she was in her late eighties. Louie became a captain in the El Paso Police Department. and later in his career, Chief of Police at El Paso Community College. He received a letter of reference from Mr. Wicks when he first joined the department.  Daniel Acosta is a Mexican American born and raised in El Paso. His grandparents emigrated to the US in the early 1900s. Daniel's parents never completed high school, and he was the first in his family to graduate from college. He has a professional degree in pharmacy and a doctorate in pharmacology and toxicology. Daniel's career spanned 45 years as an educator, scientist, and administrator in academia and the federal government. He recently retired in Austin, and plans to write about his experiences with discrimination and bias during his career. He hopes that he can help young minorities with their careers by writing about the barriers he encountered in academia, professional societies, and the federal government.

6 Comments

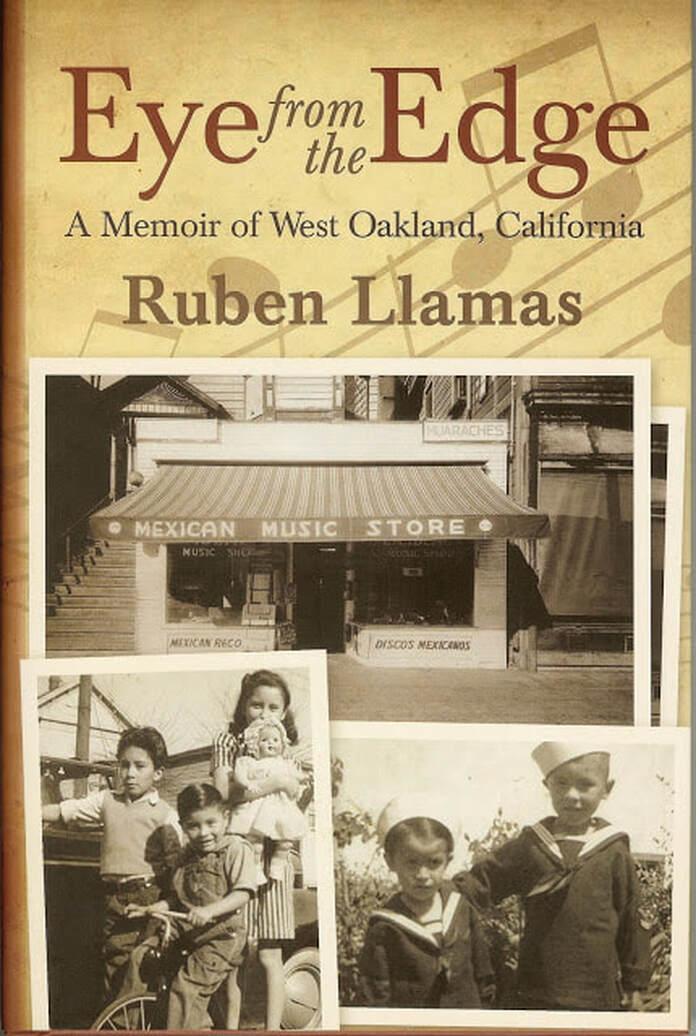

Excerpt from Eye from the Edge, A Memoir of West Oakland, California by Ruben Llamas First published on December 24, 2013, in Somos en escrito Magazine …Danny and I both stayed at St. Mary’s School for the rest of our grade school education. Education at the Catholic school was reading, math, and a lot of religion. They had a lot of rules, and boy, they enforced them 100 percent! Our parents supported these rules because they wanted us kids to get the discipline and education that we needed for our futures. The Holy Name Sisters taught at the grammar school that was associated with St. Mary’s Church. The Social Service sisters in gray habits taught catechism. Father Philipps was the pastor beginning in 1936 at this parish. We were active in most events of the school. The classes were small and the Holy Name nuns ran a tight ship. All the basics were taught. I can remember that penmanship was big. We spent a lot of time on cursive writing. English language was important. We didn't do any schoolwork with the Spanish language. The grade school was in a separate building on the lower floor. Above it was the school auditorium. We were active in school plays during the different seasons. All the classes had to participate. It was fun. I can remember starting class by reciting the Pledge of Allegiance to the American flag and then morning prayer. One of our teachers at St. Mary’s was Sister Mary Frances, a stern taskmaster with old-school ways. She taught the essential subjects and praying in class. She would have us hold our hands together with palms facing and our fingers extended. We had to make sure our palms were touching with thumbs crossed over one another in the form of a cross. If you were not complying with her instructions, she would pull your hair or whack you with her twelve-inch wooden ruler, hitting your hand and making it sting! Boy, you had to be alert in school or you got the ruler, no excuses. I remember the spelling bees and how the entire class, thirty or forty kids, stood around the perimeter of the room. One at a time we would be commanded to spell hard words. She would not let you sit down until you learned to spell the word correctly. I believe I learned a lot in her classes. Either she was tough or I got tired of holding my hands out and getting the twelve-inch ruler whack. The priests of the parish would often visit our classrooms. I can remember how she taught us to acknowledge the presence of Father Philipps or Father Duggan when they arrived. Sometimes we expected the priest and other times the priest would just surprise us, knocking and walking in. When he entered we stood in unison immediately and with a loud and enthusiastic voice greeted whoever it was, saying, "Good morning, Father." Sister Mary Frances did provide a quality education to us that helped us to succeed. Being boys, we would spend time talking about Sister. The big thing was the part of her habit she wore on her head. The habit was so tight-fitting on her head we thought she was bald or had a crew cut. We never found out. I remember she prayed a lot. During Lent she was into praying at the Stations of the Cross. Our principal, Sister Mary Guadalupe, was also into using her twelve-inch ruler. She had a large wooden crucifix with metal trim hanging from her neck. She was barely five feet tall but very intimidating in her body motions. She would use either of her weapons if you misbehaved. I remember Father Philipps pulled me up once by my sideburns when I was in the schoolyard doing something stupid. The memories of how they got our attention when we were being lazy and acting up worked. I graduated grade school, and I thank the teachers for my education that made me this person I am. The church was on the same block as the school. We put a lot of time into religion and prayer. Mass was a big thing. I helped out during Mass as an altar boy. This was an experience. I remember one priest who really liked his wine. It was something to pour wine into the gold chalice then see him drink it and get a refill. The wine was a good Napa wine. I did like the taste myself. Another thing I liked was the Latin Masses. I was learning Latin and I liked the High Masses. The funerals were very spiritual events. I liked the large candles and the holders. When I die I want the same type of candles and holders. When you served as altar boy for a funeral you got a cash tip. The school and the church were across from a park. The houses going further west toward the Southern Pacific yard were older and mixed up with smaller homes. These houses must have been built about the 1880s-1890s to accommodate the large immigrant groups. In those days people came from all over. European Americans, Africans, Portuguese, Irish, Italian, Dutch, Mexican, Japanese, and Chinese immigrants all settled in Oakland. The population in 1860 was 1,543. In 1910 it had grown to 66,900, including many folks who moved from San Francisco, especially after the devastating earthquake of 1906. During the 1940s before World War II, there was a theater on Seventh Street West called the Lincoln. We used to go there or to the Rex on Saturdays, mainly because of the double features. It was a fun day. Many African Americans lived in this area where the porters for the Pullman Company owned many of the homes. In this area of Seventh Street, many African Americans owned restaurants, pool halls, liquor stores, storefront churches, and music clubs like Slim Jenkins’, which I remember. The street was busy with people shopping, cars traveling the street, and streetcars and trains running. The west end of Seventh Street had a lot of restaurants with good southern food and music nightclubs such as Esther’s Orbit Room. The place had many southern blues clubs, attracting the young shipyard workers, new people from the South, and locals to these hot clubs of the day. In the 1930s and 1940s Slim Jenkins featured at his club some of the biggest names in jazz and popular music. The club was well-known among locals as a fun place for a night out. Other nightclubs in West Oakland were Sweets Ballroom and the Oakland Auditorium. The old-timers’ businesses in West Oakland saw the impact of the new wartime workforce. The shipyard workers would spend their money in the neighborhood. Years later twelve city blocks of this once-booming area were demolished to make way for BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit), Interstate 880, and the Oakland Main Post Office. Around 1949 I did a lot of bike riding with all my friends in these neighborhoods. This whole area had a multicultural environment. Riding through the streets was never a problem with the people. The Black kids knew us or knew that we lived in the same neighborhood. We played a lot of hardball - baseball at DeFremery Park and Ernie Raimondi Park. The local kids would hang out at the parks to have a baseball game or just practice. The parks were clean, the grass green, and the juvenile hall was next to DeFremery Park. You could talk with kids who were in confinement there. The exercise yard was just on the border of the park and we knew some of the guys. This north part of Oakland was more residential than Seventh Street. It was a neighborhood with a mixture of people. African Americans who worked for the railroad came from all over. This was especially true for the men who worked as sleeping car porters, dining car waiters, and cooks, and others who had seniority and wanted to have their home closer to their work or where the tips from the passengers were better. When the war broke out and the shipyards needed more workers, you had also African Americans from the Cotton Belt, mainly Texas and Louisiana, as well as the Okies and Arkies, moving into the established section of this area. When an old Victorian house was converted to take in a lot of these people, it was a crowd. I can remember my friend Art’s family in one of these large homes. They lived on the first floor and other families lived on the second floor or basement. Art’s house, as well as other houses east of Market Street near Eighteenth Street, was close to Cathedral of St. Francis de Sales, which was demolished after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Art had about three brothers and three sisters. His older brother was about the same age as my older brother, Mario. All of us would head over to other kids’ homes on our bikes or just hang out in the neighborhood till we had to go home. I would, on Saturday for sure, shine shoes in the barbershop. Saturdays were busy for everybody. The neighborhood was busy. People were around. They came during these times to Seventh Street to shop the local merchants. Remember, the outlying areas weren’t built up with big centers for shopping yet. People from North Oakland, East Oakland, Piedmont, and other areas would come downtown or to Seventh Street. When the barbershop was slow I would go downtown to shine shoes. The sailors and the army guys were always good for a shine. I had a spot on Tenth and Broadway, in front of Crabby Joe’s Big Barn. It was a great spot to shine shoes and sell newspapers. The military people always wanted to have their shoes looking good. They were on leave and most of them came downtown from all the nearby bases and from Alameda. Most of these guys drank a lot and loved the ten-cents-a-dance club above Crabby Joe’s. This group was always a fun group. They spent their money. I enjoyed this corner. It was exciting to see all the action around you. The people all had something going. It was a busy time for everyone, women, men, and kids. As a kid I saw the con men, gamblers, crooks, prostitutes, gypsies, and other people, all looking for a score. You learned to mind your own business, not to know or talk about what you had seen. If they trusted you, they would tell you a story or two of their activities. During this time I also sold papers, namely the Oakland Tribune and Post Enquirer, across the street in front of the liquor and cigar store. From the papers that sold, you received about three cents a paper. To me this was money coming in, plus the shine box money. I was on top of the world. As time passed, Joe, the owner, would have me run errands for him. I had no problems doing that because he would feed me pizza and a cola once in a while. Joe was the pizza maker during the late shift. He had a special window at the front where people would watch him prepare the dough. If he had people looking into the bar, he would show off, flipping the pizza in the air, and just put on a great show. The inside of Crabby Joe’s was something to see. They had a long bar from one end of the wall to the other. The brick pizza oven was toward the front. Across from the bar were tables where you could eat or drink; then came the dance floor. The bandstand was in back and had more light on it than a carnival stand. The big thing was the floor by the entrance and along the bar. Sawdust was all over the floor. This was typical of what I would call a joint. Also Joe had a large back room with tables for private card games. This old building would rock on the weekends. The music was popular country style--Okies and Western music--music you would hear on the radios of the 1930s and 1940s. This was music of the southern culture traditions that were being heard in Oakland with the influx of the newcomers. There was always some fight or something going on. The bands playing at Crabby Joe’s were well-known and played all up and down San Pablo Avenue. They would draw big crowds. It was music to make all people dance and have fun. Joe was a neat dresser. When he was not working he always dressed up. His slacks were sharp and cut well. His shirts fit neatly, and he always wore a neat sharp dress jacket. His shoes were always cleaned, shined, and casual. Joe was what I called in those days a San Francisco Sicilian Italian, with tanned skin and black wavy hair. Joe was well-known in this Broadway area of Oakland since most of the rough and tough bars and businesses were down here. The third floor of the old building had a hotel. I would sometimes run through the third floor trying to sell the last edition of the Oakland Tribune. This was an experience where I learned a lot as I did this selling. At most of the rooms, people would just not answer. The ones who did answer bought a paper and got you out of their way so they could continue their business. I would sell papers till about 5 p.m. or when I knew that the people who read the paper daily had their paper. They would always have the right amount, for they would fold it and put it under their arms like it was worth a hundred-dollar bill. They would tell you about the paper not being in order the next time they came by. The job of the paper-boy was to assemble the paper in sequence and sharply folded. While I was in the area I would go over to Fosters’ Restaurant. I know this place was not like the other places. They made a lot of sandwiches. The cream puffs and pies were great. The food was displayed in small compartments. You selected what you wanted out of these compartments that had doors. It was all self-service. You paid a cashier, then sat down at the round Formica and chrome tables. I sold the later paper here. When I was gone from my corner I would put up a cigar box for customers to drop monies off for their papers. I never had trouble with people taking my money. About 5 to 5:30 p.m., Radio, the newspaper collection man, would come to collect the newspaper money with his REO truck, a green panel truck with two doors, a double door in back, and no seat belts. Radio was about five foot six, maybe a Mexican or Italian. He had small facial features, big eyes, a great sincere smile, and he enjoyed laughing. He would pick up all the corner boys starting at Ninth Street all the way to Grand Avenue North, going up Broadway, next coming south on Washington. He would count your unsold papers and pay you off. While driving, Radio was a talker. He loved baseball. Radio was a good man. Once he gave all the kids a ride in his green REO panel truck to see an Oaks ballgame in Emeryville. The Oaks were Oakland’s minor league baseball team. After we were dropped off I would go home, visit the shop to see what was going on, then go upstairs to see my mom and get something to eat. If the timing were right, I would get my bike and search out my friends in the neighborhood. I would, by this time of day, go to Jefferson Park to see if any kind of game was going on. Across the street from Jefferson Park, St. Mary’s Church and School made a strong presence. Under the grade school they had a basement where they put in pool tables and a boxing ring to keep us boys busy. Father Duggan did this, and he had other programs to keep the young boys busy and away from the neighborhood pachuco gangs that were around our section of West Oakland. If no one was around I would then ride to Danny’s house on Myrtle Street. In the evening the wind really blew the estuary smell throughout the neighborhood. I could hear the ship and train horns on my route to Danny’s house on Third Street. Once in a while I would go down by the railroad tracks and follow them to Myrtle Street since the track went right to the Southern Pacific yard at the Point. Sometimes the guys were outside their houses. If not I just left for home to get ready for school or do some homework. At home about the only thing to do was listen to the radio. We had no TVs at that time. Friday and Saturday were busy days in the barbershop and music store. I shined a lot of shoes on the busy days. I was growing in these times, and I learned a lot about shoes. Sometimes I would go downtown to watch the Black guys shine shoes. They had a storefront on Broadway and Tenth. The small shop had four guys working it, and four stands with a lot of blues music playing. They would let me watch them and learn how to prepare the shoe for a great shine. They had a special wash for the leather. They applied the smooth-smelling shoe wax with their fingers and snapped the cotton shine rag, all in a rhythm of applying it. With the music blaring, the talking going on, it all flowed with the movement of the shiner’s body. It was an art in itself and great to watch. I would take their style of shine back to the barbershop and do my customers while snapping that rag like the pros. To this day I still have my red shoeshine box and enjoy the smell of the shoe paste we used to make those shoes sparkle. Some Saturdays the men’s discussions shared and compared the history of their countries of origin, such as Mexico, Cuba, Chile, Guatemala, Honduras, EI Salvador, Colombia, and Nicaragua. The history and cultures of all these men were interesting. I enjoyed hearing of Mexico and the Aztecs. The men talked of how the Spanish influenced each of these countries. The Spaniards conquered the Aztecs of Mexico in the early sixteenth century. The Aztecs had a great empire in Mexico City with pyramids and palaces, zoos and libraries that were similar to Egypt’s. Montezuma, the ruler at the time, had a large army. Cortés had an army of only 350 men and brought with him new diseases that killed a lot of Indians. The Aztecs had never had these European diseases. The story of the Aztecs is part of the history of the Americas and has always been an interest to me, but I don’t remember learning about them in school. At St. Mary’s School we learned about the history of the United States of America and the Catholic religion. This was basic in these times. And that’s the way it was. The men all had a story of their country and how the Spaniards exploited their country. These men that came in to see and talk with my dad and their friends were locals. They worked at foundries, at the shipyard, and as dockworkers at the local terminals. I would just listen to them and see the excitement in their discussion. I began to understand the conflicts between the Latino and the gringo cultures. The men would drink Four Roses whiskey or beer, then leave for the night. They were always dressed up so I knew that home was not their destination. I am sure of this. Some of the Saturdays before working in my dad’s shop, I would play ball at Jefferson Square Park. Baseball was my favorite sport. I played any position they gave me. I always enjoyed the game. Some of the guys played daily, and they were good. Saturday morning during the summer we played in a city league. The police department organized these games for all the kids in West Oakland. They had an old paddy wagon. They would pick us up at Jefferson Square Park and take us out to the city park in Oakland. We played all the teams. Then at the end of the season you played the City Best. It was fun. We met a lot of kids from the other parts of Oakland, mostly ages twelve and thirteen. We never had any problems with the different multicultural groups. I believe we all understood that we came from different and tough neighborhoods so why get an attitude. We would just fight it out. Some of the boys were good players. They also liked a good fight and that did happen once in a while. If you came from West Oakland Seventh Street, they seemed to leave you alone. Our Seventh Street in West Oakland had a bad reputation during these times.  Ruben Llamas, born in Oakland, California, just before WWII broke out and changed all our lives, recalls what it was like to grow up in a bustling time in diverse neighborhoods which urban development wiped out. From shining shoes in front of his dad’s music store, he rose from being a shopping cart boy of a retail company to its vice president. He now lives in Carmichael, California, with his wife, Anita. Editor’s Note: I grew up in East Oakland on the other side from where Ruben grew up and remember well how different the 1940’s and 1950’s were from today; Ruben’s story strikes the ring of truth. Those were the days, my friend. His memoir is available through Earth Patch Press, www.earthpatchpress.com, or online booksellers. An Eye for |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed