“Piano”by Linda Zamora Lucero Papa’s funeral, spring 2009. In the tiny chapel are my sister Ellie and her clan from Phoenix, my brother Tito, both of Tito’s ex-wives, and Papa’s best buddies—Montez leaning on his cane, Garcia in his wheelchair, reeking of cigar—both retired welders from Hunters Point shipyard. Papa radiated so much love even my newly ex-boyfriend Julián shows his face to pay final respects. Only Mama is missing. When Tito went to pick her up, she insisted she was too distraught to come. Great, I think, although I don’t believe it for a second. Sure enough, just as the service begins, she materializes in the middle of “Gracias a la vida” in a red coat and yellow hat with feathers. “I don’t need help to sit down!” Mama says, slapping the usher’s hand away. “You’re late,” I whisper, grudgingly making room for her in the pew. Dressed up for Papa, I’m wearing a fitted black dress with tiny hand-sewn turquoise flowers, a Oaxacan shawl, large hammered gold hoops, black hair pinned up. “Hello, Raquel,” Mama says pleasantly, sitting on the fringe of my shawl. “Such beautiful music.” And she commences to hum along with the vocalist. Yanking the shawl loose, I close my eyes and pretend she isn’t there. **** After the service, our family gathers at Tito’s house, where we wolf down plates of homemade chile verde, throw back shots of Herradura and recount the same cherished stories we always do whenever we get together. A favorite is how one Thanksgiving—this was before Mama abandoned us—we children were squabbling over the drumsticks—and Papa asked if he could just this once have some peace around the table. Seven-year-old Tito, thinking he was being real hilarious, smugly handed Papa the bowl of peas, whereupon Papa angrily slammed his fork on the table. We watched in horror as the fork slowly became airborne and cracked the kitchen window. We ate in chilly silence until the pumpkin pie with whipped cream made us boisterously happy again. Tito says, “’Member?” We laugh at the timeworn anecdotes, fall silent with grief. At the ripe age of thirty-nine, Ellie gets up to dance, leading us in a raucous chorus of “Papa Was a Rolling Stone.” Missing Papa’s delighted belly laugh at his youngest daughter’s antics, I suppress a shuddering sob. Ellie’s kids bickering over a toy feels like the saddest thing in the world. Tito brings Mama a cup of té manzanilla and fusses over her. She eyes the proceedings from a corner armchair, the feathered hat like some ridiculous canary atop her head. She’s on her best behavior. Of course, it doesn’t last. Barely three weeks pass before the director of the Thirtieth Street Senior Center calls me at Galería Libertad, the community art center I direct, asking to meet with Mama’s family, meaning Tito and me, since Ellie is safely back in Phoenix. Thirtieth Street is where Mama eats lunch on weekdays, takes piano classes, and is an active member of Mr. Topper’s Mission Tappers, no tapper under seventy-five. Before he died, Papa spent his Saturdays playing poker at Thirtieth Street. “I realize this is a difficult time, so I do apologize,” Mrs. Whitmark says, her lipstick pomegranate pink. She pauses, looks up through bifocals, and an all too familiar despair washes over me. To most people, Mama is an eccentric elder with a mind of her own. Some of us know otherwise. “Mrs. Flores is accusing people of stealing from her purse. Everyone is suspect—the other seniors, the janitors, the cooks, even myself. It’s quite upsetting. Your father helped calm her whenever she got this way, and now we need her family to step in.” “Of course,” Tito says, nodding. “We’ll talk with her.” Tito is a machinist for the transit system. He’s completely overbearing, but somehow women find him fascinating. He’s been married twice with no children, while I can’t seem to find my match, romantically-speaking. Tito has no idea what I do at Galería Libertad. He teases me by introducing me to his friends as “my sister, the starving artist,” and he’s not far wrong. But in the Mission arts community, I have found friendship, love, sustenance. My home. “Losing Dad hasn’t been easy for Mom,” Tito continues. I love my brother, but when it comes to Mama, he ticks me off. “She’s crazy,” I say flatly, brushing a strand of hair from my eye. After Papa’s funeral I’d shorn my long hair into an asymmetrical what-I-hoped-was-stylish cut. Tito shoots me a foul look. But crazy explained my mother who, one ordinary morning after Papa had gone to work, made us children breakfast and sent us off to school, then took a train back to her hometown in New Mexico. To stay. Tito was ten; Ellie, six. I was twelve. In the chaos that followed we all pitched in to help Papa with shopping, cooking and housekeeping. That was the easy part. After Mama left, Ellie suffered from debilitating headaches and Tito was suspended from school every other week for one thing or another. Papa began drinking heavily. There was no one to turn to. My parents had grown up in New Mexico, but we were born and raised in San Francisco in four rooms on Shotwell Street, miles away from kinfolk who gossiped about the neighbors, shushed children at weddings and offered solace when worlds shattered. I was raw with anger at Mama, praying that she’d return to us, declaring that she wouldn’t dare. “Maybe,” my best friend Anna said, “she ran off with a lover.” Prone to dramatic flights of fancy, Anna with her black cat’s-eye glasses concocted wildly romantic stories about our favorite middle school teachers. Now she had one for my mother. Maybe you can just shut up,” I said. A weak response, but heartfelt. Crazy explained Mama’s sudden reappearance in San Francisco five years later. That was the first time a social worker told us Mama was “mentally and emotionally unstable.” But I knew he meant crazy, and for that I was grateful. It explained her crying jags, her periodic paranoia, her denials that she needed help, her refusal to take prescribed medication. Crazy summed it up. In Mrs. Whitmark’s office, Tito loudly clears his throat and promises that he will get Mama to take her meds. “Good luck,” I say, grabbing my daypack. Tito is uncharacteristically silent as we leave Thirtieth Street, his broad, good-natured face splotchy. As soon as we reach my beat-up Toyota, he lets loose. “You were out of line, Rocky, calling Mom crazy! She’s our mother!” Tito and Mama wrote each other regularly after she left. She worked in a café near Taos, and, as we found out later, had reconnected with a high school flame. I was horrified. Tito and Ellie visited her summers, but I refused. When Mama returned, my siblings were elated, being younger and obviously needier than I was. In the five years she’d been gone, I had become 100% Papa’s girl, Athena sprung from Zeus’s head, full grown and battle-ready. Papa never dissed her, but I held her responsible for his alcoholism, his melancholy, for all of us having had to answer endless questions from teachers, busybody neighbors, and shitty strangers who felt sorry for us. Because what’s more pitiful than motherless children in a strange land? So when Tito says, “She’s our mother,” I say, “You’re entitled to your opinion, Tito. I have to go. We have an exhibit of Cuban posters opening in a week.” “Weird haircut,” he snorts. He gets into his car and peels out, as if he were sixteen instead of forty-one. I burst out laughing as his Midnight Blue Chevy leaves fat skid marks on the asphalt. The next time I see Tito, I’ll ask about his prize roses. We Flores don’t say Sorry, even when it’s called for, or a straight-out up-front I love you, even though we do. After an argument, when one of us asks about the weather, it means I’m over it. Dancing salsa after a backyard barbeque means I love my family, or I love the whole fucking world and everything in it. Things go unsaid for days, even years, the love, anger or sorrow pent up inside like a great accumulation of molten lava below surface, wanting release. It’s the Flores way. Friday evening, I’m at home on the computer, writing wall text for the exhibit, half listening to Jeopardy. The category is “Shakespeare,” the answer is “Doubtful Dane.” My cell buzzes—Ellie in Phoenix. I ignore it. We used to watch Jeopardy, Papa and me. He admired Alex Trebek. Debonaire, brainy and not above showing it. A contestant hits her buzzer and shouts “Who is Hamlet?” On Ellie’s third call, I answer, muting the TV. “Mom’s not answering her phone,” my sister says. “I wasn’t answering my phone either,” I chuckle. Ellie ignores me. “Mom was perfectly fine yesterday—Tito says she’s taking her meds, but now I’m worried.” Usually, Ellie asks about what’s happening at the Galería, or about my mostly pathetic, sometimes hilarious dating forays in the six months since I broke up with Julián. Not this time. “Have you seen Mom since the funeral?” On television, Alex Trebek’s lips announce Final Jeopardy, inspiring looks of consternation in the contestants. The category is “San Antonio, Texas.” “Remember the Alamo?” I ask Ellie, wishing she didn’t live so far away. I miss our sisterly heart-to-hearts over her homemade biscochitos and wine. “Come on, Rocky, would you just get over there and check on how she’s doing? Tito’s in L.A. this week.” I sigh loudly, meaning yes. “Great! Love you!” she says, and hangs up. And the burden shifts to me. Mama lives in the same paint-peeling, rent-controlled Edwardian flat we were raised in, located in the heart of the Mission—what the realtors gleefully call “a neighborhood in transition.” No doubt. Since 1492. The door cracks open. “Hi.” I slide my foot inside before Mama can decide whether or not she wants a visitor. “It's me, your daughter.” “I know.” Hazel eyes peer up at me through huge red eyeglass frames. Mama is queen of her private little planet. She’s wearing a crimson apron with gold rickrack trim over a blue sweater shot with silver on top of a fuchsia dress. Purple leggings, lambswool slippers and a silver “Hottie” pendant complete the look. We are nothing alike. Born in the history-rich Abiquiú, New Mexico, Mama grew up speaking Spanish but she looks like a gringa with pale skin, auburn hair, light eyes like a wary cat. I’m dark like Papa, and proud of it. His first language was also Spanish, but his maternal grandparents were Taos Pueblo. I dress in black: turtleneck, jeans, boots. I do rock the earrings, however; the showier, the better. Today’s earrings are humongous crimson Lucite hearts, a gift from a Oaxacan artist. “What happened to your hair?” Mama says. “Why don’t you answer your phone?” I counter. The flat smells of Papa’s Tiger Balm and tobacco. I have to stop and catch my breath. “What’s wrong with you, fighting with me already?” Mama looks down the street before closing the door. “I thought you were someone else.” Her tone sweetens. “How are you, anyway, Raquel?” An ordinary question in an affectionately maternal voice, perfectly calculated to derail me. She does this every so often, and when she does, my heart flips like a kite in high wind, and I wonder what it would be like to have a real mother. Would we go to museums together? Would we shop for shoes, get our nails done? What do regular mothers and daughters do? The question slams into me whenever I run into girlfriends with moms, enjoying themselves. Mama hadn’t been there to help me buy my first bra or see me win first prize in a high school art contest. There was more I’d missed, things more profound. I just didn’t know what. The hallway is piled with boxes. “What’s this?” I ask. “I called Goodwill, but they’ve gotten choosy…your father kept everything: clothes, magazines, rusty tools.” A wave of fear hits me. “Goodwill? Where’s his brown suitcase?” Blood thunders in my ears. I catch a glimpse of myself in the hallway mirror. I look exactly the way I feel, bug-eyed and off-kilter. “There’s more in the garage. Not interested in old junk. Old junk, old men, old ideas.” Mama laughs, apparently delighted with herself. Old junk? “Please, please, don’t give anything away! I’ll get Tito to bring his pickup next weekend and we’ll take it all.” She disappears into the front room where the furniture—sofa, coffee table, Papa’s La-Z-Boy—has been moved against the walls. She pulls aside the lace curtains on the bay windows and looks out to the quiet street. “The piano should be here by now.” “Piano?” She doesn’t need a piano. Tito gave her an electric keyboard on one of her birthdays. It’s programmable, so that she can play tango, classical or her pop favorites. Papa would read his detective novels in his recliner, foot tapping while she plinked out Beatles tunes note by note. I never understood why he took her back. “Respect your mama,” Papa admonished me when I gave her attitude. “No matter what, she is your mother.” Respecting Papa, I shrugged. I was seventeen when she returned to Shotwell Street, my eyes were already focused on college and the wider world. Turning from the window, Mama says, “Can I borrow ten dollars until Friday?” I dig into my bag and hand her a ten and a twenty. “Just keep it.” I feel vaguely virtuous, giving her something without begrudging it. “I said borrow, Raquel, and only ten until Friday when my social security arrives.” The folded bill disappears into her apron pocket. “Whatever. I’ll have some water and then I’m out of here.” Running the faucet in the kitchen, I check for signs to report to Ellie. Cereal bowl in sink, oatmeal encrusted. Golden moth orchids I’d bought for Papa at the Alemany Farmer’s Market, shriveled and fallen onto the windowsill like exploded firecrackers. Portrait of the recently-elected President Obama. Wall calendar from La Palma Mexicatessen, inked Xs marking the days. Today is April 6. No X as yet. Mama is right on my tail. “I pay my debts. I’m not like that Julián of yours. He still owes me money.” Here we go. “Jeeze. It was change for a parking meter.” I feel my temperature rise. “I’ll repay you! And you can forget Julián because Julián and I are not together!” Papa’s eyes got cloudy as he aged, but not Mama’s. Her eyes are like new-minted dimes, bright with gotcha. “I don’t forget. Julián shouldn’t be borrowing from old ladies. I’m glad you’re rid of him. It’s better to be alone, Raquel. You’re smart, like me. The smartest of my children.” I’m floored. Mama has never expressed the slightest interest in my life or anyone else’s for that matter. Although mortified by the comparison, I can’t help being flattered that she considers me the smartest. “So,” I say, softening. “You’re renting a piano?” Her arms fold defensively. “It was on sale.” “You bought a piano?” Baffled, I pull out a chair and sit at the kitchen table. “For my music lessons, Raquel.” Still standing, she bristles with nervous energy, her pendant flipped so that it reads “eittoH”. “What about the keyboard Tito got you?” “I need a real piano. Besides, Tito steals from me.” Yup. Genial to eccentric to crazy at maximum velocity. The woman who brought me into this world is fundamentally incapable of being the mother I long for. I know this in my heart, in my brain, in my gut, in my very pores, and yet she gets me every time. I rise to tighten the dripping faucet, then turn to face her. “Look, Tito’s here every weekend, and when he can’t, he calls to see how you’re doing,” I say, defending my brother. “Why do you give him such a hard time?” A better question is why am I trying to reason with her? “You know damned well I can’t trust him.” I take slow, deep yoga breaths. Do not engage. Do not engage. Mantra for Mama. Outside, a vehicle rumbles to a stop. “It’s here!” she says. I follow as she rushes down to the sidewalk, patting her hair in the mirror on her way out. A deliveryman in a maroon jumpsuit strolls toward us from a double-parked delivery truck. “Piano?” he asks me. He has sleepy eyes, a pencil-thin mustache, a clipboard. “You’re late!” Mama says. “Sorry, ma’am.” He tips his cap back. “I’m Jesse and that’s Murphy.” Murphy is pulling a ramp from the back of the vehicle. Mama ignores Jesse’s proffered hand. “Where does it go?” he asks me. I blink, smiling. “I’m just an innocent bystander.” “Up here,” Mama interjects, leading us up the steps and into the living room. “You ordered a Yamaha grand?” Jesse is finally addressing questions to the right person. “Ma'am, we get a nine-footer in here and you won’t have room to sit down and play.” “There must be a mistake,” I say. “I don’t need much room,” Mama says, shooting me a dark look. “Move, Raquel, you’re in the way.” So be it, I think. I’ve always been in your way, we all have, Papa, Ellie, Tito. You could have continued therapy, taken the pills, and avoided the crises that your family—not that you recognize us as family—have had to rescue you from over the years. Selfish, selfish, selfish. I back myself against the hallway wall as the movers expertly rotate the piano to make the tight turns. Well, I’ve done my duty. My report to Ellie: Mama is alive. Mama is well. Mama is impossible. “I’m coming back this weekend for Papa’s stuff,” I say, “and will you please answer your telephone? Because Ellie and Tito worry about you.” As I take off, I hear Mama telling the deliverymen, “There’s ten dollars for you when you’re done.” **** On Sunday Tito is wearing his annoying “I’m just a regular vato from the barrio” get-up—Ben Davis work pants and his “Stay Brown” t-shirt from the San Jose Flea Market. We’re both wearing Giants caps. The sun is out, there’s a game this afternoon. I’m anxious to get back to the Galería where volunteers are painting the walls. “We’re here for Papa’s things,” I say, when Mama comes to the door. She is channeling Cher today: red tunic, shaggy vest, ankle boots. Gray wisps escape a blue-sequined beret the size of a small pizza. “God, open a window! Aren’t you hot?” “Leave me be, Raquel. You know I’m always freezing,” she says. “I'll make coffee now that you're here, Tito.” My brother is definitely her favorite child. There are times I believe he is the only person in the world who can get through to Mama, but when I really think about it, I shake my head, No. Because after his visits she accuses him of stealing and she cries. Always. “Momskh!” Tito says, draping his beefy arm around her shoulder, “Where’s the pianoskh?” Mama’s eyes light up. Tito has invented this Russian-esque language just for her. “Who told youskh?” she giggles, leading us to the living room. Tito halts theatrically in the doorway, throws his hands up in wide-eyed astonishment, “Whoa! That’s some piano!” The piano is impressive, gleaming ebony, padded leather bench tucked underneath, filling the room like one of those clipper ships crammed inside a tiny glass bottle. “What do you think?” Mama is giddy. “What do I think?” Tito bellows. “What do I think? Takes up a lot of space!” Somehow this is the right answer. Mama practically squeals with pleasure. If there were room she’d be pirouetting around the piano. “It's ridiculous,” I say, addressing Tito. “If she needs a so-called ‘real’ piano, which I doubt, a used upright makes more sense.” Tito’s look tells me to can it. “This is a piano for professionals,” I emphasize, unable to help myself. I’m the director of a community arts center. I believe that everyone has the capacity to make art, to enjoy a creative life. This is my work, yet I can’t manage to extend this value to Mama. I feel like a miserable imposter. “I love it,” Mama says, defiantly. “Play us something, Mom!” Tito doesn’t have to ask twice. Mama climbs onto the bench and sorts through dog-eared sheet music. She begins playing “De Colores” and Tito, leaning over her shoulder to read the lyrics, sings with her. Both are seriously off-key. I escape, taking the kitchen stairs down to the backyard where weeds are suffocating Papa’s tomato plants, and enter the garage from the side door. Underneath the floorboards, the caterwauling is mercifully muted. Papa sold his car awhile back, so the garage is now storage space. I wade through boxes and furniture before I find what I’m looking for: Papa’s brown leather suitcase. Wrenching it free, I wipe the cobwebs with an old t-shirt and sit cross-legged on a box, my heart at peace. The tarnished metal fasteners make a satisfying pop. Lifting the lid, the faintest scent of tobacco in the yellow silk lining sweeps me back to another time. It must have been fall. The living room windows were dripping condensation. Mama had been gone a year. I was still crying myself to sleep. Papa set the suitcase on the coffee table. “Let’s see what we have here,” he said, a cigarette in one hand, a can of beer nearby. His hair was still coal-black, but he was starting to get a paunch. He’d drag out the suitcase now and then, often during the holidays, to show us his treasures—a jumble of photographs and souvenirs—a pretext for his stories of back home. That day it was only me sitting by his side on the worn sofa. I reached for a sepia-tone studio portrait of an elegant native woman in a 1940s fur coat. “Who’s this?” I knew the story by heart, but I never tired of his stories of wicked uncles and chain-smoking grandmas, homesteads and adobes, farmers and dressmakers, sheepherders and coal miners, pueblos and penitentes, trains, abductions, adoptions, fires: tales of love, tragedy and survival reaching back across generations to New Mexico Territory and beyond. “My first cousin Josie, on my mother’s side. She had a tailoring shop in Santa Fe. She was a sharp cookie, married and widowed three times, the last husband a Navajo. She liked them young but it didn’t matter. They still died on her.” We chuckled. I pulled up an unfamiliar snapshot of a couple picnicking on a blanket at Ocean Beach, the Cliff House in the hazy distance. “And this one?” A shadow crossed Papa’s face. With a sinking heart I recognized my youthful parents in a happier time. Silence flooded the room. Papa’s thoughts seemed to alight on something not in the picture, the ashes on his cigarette trembled. Finally, he smiled, seemingly chagrined by his thoughts. I switched the photo for one of Papa as a boy and his older sister posing in front of a Ferris wheel. “I wished I’d known Auntie Rose,” I said. Papa never returned to New Mexico after he and Mama moved to San Francisco—his immediate relatives had moved away or died by then. If there were other reasons, he never shared them. “You remind me of Rose, mi’ja,” he said. “Sparky as hell.” Besides photos, there is a ledger of the early 1900s written in Spanish and English, discharge papers, faded postcards from distant relations we children never knew, yellowed newspaper obits, a ruby ring won in a poker game, a ring neither ruby nor gold. This is what I came to rescue from Goodwill. My father’s life in a suitcase—all we have left of him besides his stories etched into our memories, tales that kept our family tethered to our history, to this land, to each other. I secure the suitcase, one snap at a time, and haul it up the back stairs to the living room where Tito and Mama are hammering out “That’s Amore.” Tito insists on getting burritos and a six-pack for lunch. We dine on the kitchen table of our childhood, while Tito tells us about his new lady friend, a teacher. Mama tracks his every word, the better to throw in his face one day. Tito is oblivious. Someone in the building has the game on, radio turned full blast. “The bases are loaded with two men out! Herrrrrre’s the pitch!” When we were kids, listening to the Giants with Papa was the best. Halting in the midst of whatever we were doing—peeling potatoes or washing the car—to visualize the players at the ballpark, we held our breaths, waiting to hear Jon Miller yell, “The ball is up, up…it’s out of here!” My spirits lift remembering how we’d yell and high five each other. Then the heaviness in my chest returns. I claim the suitcase when it’s time to go. The rest of Papa’s things will go into Tito’s garage until Ellie can come out to help sort it all. On the sidewalk, Tito stretches and grins. “Mom’s doing okay,” he says. “We’ll just have to check in on her more often.” “Do you know what a piano like that costs?” Tito’s smile vanishes. “Don’t worry about it, Rocky, I got it covered.” “She can’t wait to get rid of his stuff.” “You can’t know how anybody feels except for your own damn self.” Tito’s voice is hard. “Mom does the best she can. You’re past forty. Is this who you want to be? We grew up with her too. And what’s with that haircut?” Glaring at my brother, I slam the trunk lid closed and get into my car. Wiping away tears, I turn onto Valencia Street, glad to be heading to the Galería. Three signal lights later, I realize I’ve forgotten my Giants cap and make a U-turn in the middle of the street. On Bartlett I drive by two little girls playing hopscotch on the chalked sidewalk like Ellie and I used to do, and pull up in front of the Lermas’ building that has a For Sale sign. Sal is sitting on the stoop, drinking beer and listening to oldies on KPOO. “Hey Rocky. Sorry about your father,” Sal says, as I exit the car. “We lost a good man.” “Thank you.” I’ve known the Lermas since forever and wonder whether they’ve found a place to move to. Before I can ask, I’m distracted by the faint sound of music coming from Mama’s flat. I climb her stairs and peer through the open bay window, past the lace curtains, where she sits half-hidden behind the big, lacquered instrument. Her fingers strike the keys as she squints through her enormous, red-framed glasses at the sheet music, her voice tentative. “Sweet dreams till sunbeams find you…” The playing is measured and precise. The voice not so much, even as it picks up tempo and exuberance. “Sweet dreams that leave all worries far behind you…” I take a breath as my heart unexpectedly catches on a surging memory of Mama sitting on my bed when I was a girl, singing me to sleep. Cozy in pajamas, bed covers pulled up to my chin, lulled by her voice, drowsy. Back when she was still my Mama. “And in your dreams, whatever they be…” Mama warbles with joyful enthusiasm. The afternoon’s heat has eased. Rising above the ambient sounds of the street—a plane overhead, a skateboarder rolling past—is my mother’s voice falling in and out of tune like a kid learning to ride a two-wheeler. Mama in her blue-sequined beret is swaying, creased fingers moving over the black and white keys of the piano, focused on the task, determined like all of us to catch beauty in this precarious life. The sound of the music awakens a raw tenderness in me, if only for the moment. Brushing unexpected tears from my eyes, I sink onto Mama’s front steps to listen.  Linda Zamora Lucero is writing a collection of short stories set in San Francisco’s multicultural Mission District where she was born and raised. She identifies as Chicana, and attended Mission High School, City College of San Francisco and SFSU. Her published short stories are: “ZigZag,” LatineLit Magazine, 2022; “Speak to Me of Love,” first prize winner, DeMarinis Short Story Contest, Cutthroat: A Journal of the Arts, 2021; “When It Rains,” Yellow Medicine Review, 2020 Pushcart nominee; “Mexican Hat,” Puro Chicanx Writers of the 21st Century 2020 Anthology; “Balmy Alley Forever,” Yellow Medicine Review, 2016; and “Take the Money and Run–1968,” Bilingual Review, 2015. Lucero's day job is directing the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival, an admission-free outdoor performing arts series in San Francisco.

0 Comments

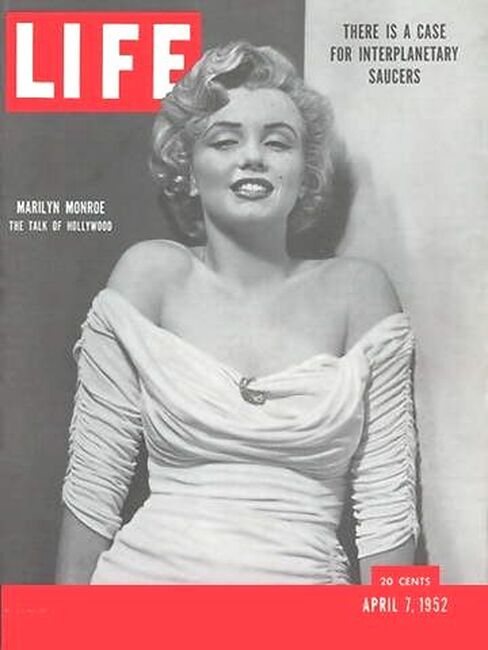

Chicano ConfidentialThe Unspeakable Truths about La LocaBy Sonny Boy Arias My morning started out just like any other early summer morning day along the Big Sur Coast, Califas. I drove down the hill to the market at the Big Sur River Inn to gas-up my VW Vanagon with two extra-large custom gas tanks. I was sure to clean the bugs off the windshield in order to enjoy the scenic route, arguably the most beautiful in the world. While my tanks were filling up, I walked into the Big Sur Market for a Grab-and-Go egg burrito made con mucho amor (with love) by Maria who rolls up gordita tortillas like my Nanita used to make to include a dash of green chile and a cup of fresh hot café de la olla. It’s a breakfast made for stone-cold Chicanos – priceless. Add to this a little touch of Los Lobos’ hit song Maricela, played over my Blaupunkt German-made speakers (with a lot of bass bottom just like the low-riders love and why the Germans love low-riders) and you realize that life doesn’t get much better – and then as if without notice, it does, life gets better, Chicano life suddenly gets better. Once the gas pump reached $100 on the first tank, I had to close it and open up the pump for the additional gas tank that would most likely take another $100. As I reached over to line-up my favorite music CDs, Los Lobos, Santana, Ozomatli, and Los Lonely Boys, I noticed the Chicano Batman CD was missing – it is probably stuck somewhere between the seats – somehow the order of the songs contributed to the momentum at which I ate the burrito and sipped the coffee, you must know what I mean, the same thing happens when eating a chorizo burrito while trying to balance your hot cafecito. Above the early morning chattering of the local Surf Bird, Barn Owls and Rock Doves I could hear singing on the other side of the gas pump. I had never heard such loud singing while filling up my gas tanks. It was difficult to decipher the singing on the other side of the gas pump because I was focused on the video feed running a story about a 65 year-old guy who was just eaten by a shark. The guy was only sixty yards off the coast at Ka’anapali Beach in Maui, the same stretch of beach where I introduced swim fins and open-ocean swimming to my 6 year-old grandson when he took off like a fish. The 65 year-old was on the first week of his retirement and the last day of his vacation, and that morning had turned to his wife, stating, “Honey, I am going on my last morning swim;” boy, did he get that right. As the singing on the other side of the pump got louder, it also got better so curiouser and curiouser I became. The singer on the other side of the gas pump was a young woman known to many as “La Loca.” She reached out to me as if it were a personal matter, “I just watched my favorite Mexican show, Tengo Talento, and have become very inspired to sing again!!” she said and then she adds, “This 17 year-old girl, Rosa Rochín, kicks some serious ass and so does her famous grandfather Buenaventura Rochin-Diazsalcedo! I think these are my people because they are very tall Mexicans, like me, from Guimichil, Sinaloa. Historically, my people were runners, they used to run messages between towns out in the middle of the desert, maybe that’s why I am so tall, and also a marathon runner.” Pointing to her tan muscular thighs, she adds, “Look at these legs; these are goddam long legs made for running. I have to buy jeans with leg sizes from 37 to 38 inches in length, that’s goddam long for a Chicana. I run the Big Sur Marathon every year!” While I glanced over at the rapidly spinning numbers on the face of the gas pump nearly reaching another 100.000, La Loca starts singing again and the amount on my meter catches her eye; she then tells me, “Man, you have to start singing to the gasoline.” I thought, “What the …?” and all at once, as she turned off the video feed on my gas pump, blurts out, “Hey vato, I said you need to sing to the gas, that way you will get better mileage” and she said it again, “Sing to the fucking gas and you will get better mileage.” All at once, she seemed like the type of person that not only demands sudden attention but that also raises all the spirits of everyone she is around. Today was her birthday, she asserted, “I was born on the same day as JFK, John Fitzgerald Kennedy!” Now, I thought, “That’s interesting!” and replied “I was born on the same day as St. Paul the Apostle.” I made sure to point this out because I always feel like I don’t get any respect the same way St. Paul did or Rodney Dangerfield or Aretha Franklin, so like St. Paul I have struggled with this my whole life. If you never met La Loca she was a sight to be seen for sure; she wore unbelievably beautiful headpieces that must have been influenced by her Esalen Indian and Mexican background and her great grandfather to be sure – as you got to know her you could see a vibrant and odd beauty rarely found. At first you might look at her and think, “There is something about this young lady that I find very attractive,” but you can’t put your finger on it, and then you zero in on her head piece and find that you can’t take your eyes off of it; plus it causes deep reflection when she leaves. It seemed that the locals know her and her family, but I did not; somehow in all the moving and grooving I do in both Northern and Southern Big Sur I missed meeting her. I soon found out why. I never really gave much thought to why locals called her, “La Loca,” that is, until my neighbor on Parrington Ridge (the one who boasts about living behind seven locked gates), told me that when La Loca was a teenager she had a “nervous breakdown” in the Monterey County Courthouse when her great grandfather was presenting his case about his land to a judge. The case surrounded the fact that her great grandfather had built a house years ago on a cliff in Big Sur without a permit. He had been there for so many years that everyone assumed he owned the land and had a permit, but he did not. La Loca and her parents had been raised on the property in question, so again, no one ever bothered to ask about a permit until now. You see, her great grandfather, an Esalen Indian, showed up in court with a beautiful hundred year-old head dress trying to make a case for obtaining a permit to extend his log cabin on the cliff. He had heard during the fire of 2016 that this was the right thing to do, but again, the reality was that he didn’t own the land in the first place, so in the eyes of the California Coastal Commission they could not legally approve a permit. When the judge as well as several commissioners made this clear, in their shitty way, while both disrespecting and speaking down to La Loca’s great grandfather, she lost it and became immediately incensed. La Loca’s great grandfather, grandfather, father, mother and extended family all became confused because again, they all assumed he owned the land. It was, to say the least, devastating to the entire family as well as to their friends and other supporters – There must have been 300 supporters in the courthouse that day. Great grandpa didn’t really know what the big deal was. Great grandpa’s supporters felt the commissioners were flexing their muscles and wanted to use him as an example to show the locals of Big Sur that they all had to have permits in order to, not only hold onto their homes but also to add on to them as well. Plus the insurance companies were now requiring proof of ownership (this all started following the 2016 fire) or they would not be insured. During the court case, La Loca had just started taking Chicano Studies classes at the Monterey Peninsula College, while at the same time working as a grounds keeper at the Esalen Institute. In both of these settings she learned that land had been taken from Mexicans in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (signed in nearby Old Town Monterey) and from the Esalen Native Americans in Big Sur. As a direct result, she became obsessed with the idea and on the day her great grandfather showed up at the Monterey Courthouse, she made this connection to her biographical past, so she blew a gasket, but she most certainly did not have a “nervous breakdown” the way it was depicted. Moreover, she was really pissed-off, but there is a major difference. La Loca showed up in court that day in one of her elaborate headpieces and began pointing to flowers on her head as symbolic examples and case studies in support of the idea that her great grandfather should be approved for a permit. Her headpiece was an excellent symbolic gesture of visual and public political art. Nay-sayers said she was “crazy” and that she was having a “nervous breakdown.” In his capacity as a local from Big Sur, the judge knew this was not the case, and so, too, did the commissioners, but no one came to her defense because the unspeakable truth was that just about everyone in the courtroom that day was breaking the law or out of compliance in the same way as her great grandfather. It was common knowledge that most people did not have permits for their homes no one had ever bothered to ask. Many locals are in fact, living on land they had never purchased, nor had acquired a permit to build onto their homes as evidenced by the insurance companies that decided not to re-insure Big Sur homes following the fire of 2016. During the course of the hearing, La Loca kept repeating Rudy Acuna’s concept of “occupation” to the judge. At one point she was screaming at the top of her lungs while in the courtroom “What is so different in our peoples squatting on the land than what the White man did in occupying our land. What is so fucking different!?” (See Rudolfo Acuna’s epic book, Occupied America.) As the judge shouted, “Order in the court, order in the court!!!” he slammed his gavel down with enough force to ring the bell at the strong man tower at a local circus; it was self-evident that he was doing the wrong thing. The judge was using the full force of his office, as well as that of the California Coastal Commission to sell out La Loca as well as all of the people of Big Sur, especially the Esalen people of which the judge’s DNA proved to be similar; everyone knew it, but he acted like a judge with his hands tied. “The law is the law!” just like Fidel Castro as he single-handedly murdered hundreds of Cubans with a shot to their heads as they were caught trying to leave the Island of Cuba. “The law is the law!” he uttered while pulling the trigger. Things got heated so quickly in the courthouse that day, emotions were flying in every direction. “Young lady, I am holding you in contempt of court!” said the judge and he ordered the county sheriffs to “take her away.” As they struggled with La Loca it was evident that she was strong both physically and mentally as it took three obese Latino sheriffs to take her down to the floor and handcuff her. As they did, she yelled out, “I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept…” [Angela Y. Davis.] After this episode, the locals in Big Sur resented the judge’s actions to the extent that he was soon voted out and so, too, were the assemblyman, congressman and senator, all representatives of Big Sur. The unspeakable truth was that everyone in the courtroom that day could have been charged with not having a permit to build or expand their homes. Everyone knew it, but no one dared mention it. La Loca became the scapegoat and was sentenced to four years in the Atascadero State Hospital for men, that’s right for men, as the judge must have screwed up the paper work. As a result, for many years La Loca was nowhere to be seen; she could not be found anywhere along the steep cliffs or singing dying whales or walking with the condors on the beach, not even singing to the gasoline pumps, as she had been officially assessed as “mentally ill” and put away in the State hospital. Several years later when she was released, she pulled out her old camera and began talking pictures along the coastline near Bixby Bridge just as she had done before being committed. In so doing, she found a white and blue hardhat that read “CalTrans,” so she put it on. Within just a few minutes, a CalTrans truck pulled up beside her and inquired about both her activities and the hat. They ordered her off the property where she was taking pictures and she must have given them the look because as she reported, “They became very stern” but when she opened up, once she shared her story they realized whom they were talking to and felt empathy for her. The two men, one from CalTrans and another from NASA started by giving her the hardhat, followed by a rationale for why she needed to get off the property. They went on to gain her trust by sharing a story that she could never share with others. The guy from CalTrans said they had planted several hundred acres of buckwheat plants on the steep cliffs in order to keep the cliffs from sliding into the ocean. And the guy from NASA said that the buckwheat attracted the blue-winged butterfly and that they were performing top secret research on how to spot the butterfly from outer space. It’s true!  (Source: ANU Open Source image: http://www.photonicsviews.com/butterfly-wings-open-door-to-new-solar-cells/) (Source: ANU Open Source image: http://www.photonicsviews.com/butterfly-wings-open-door-to-new-solar-cells/) In a confidential report to NASA, Lead Researcher Niraj Lal from the ANU Research School of Engineering, said, “Engineers have invented tiny structures inspired by butterfly wings that open the door to new solar cell technologies and other applications requiring precise manipulation of light. The inspiration comes from the blue Morpho Didius butterfly, which has wings with tiny cone-shaped nanostructures that scatter light to create a striking blue iridescence, and could lead to other innovations such as stealth and architectural applications.” In the manner of public protest, La Loca wore a sizeable piece of a buckwheat plant in her headpiece. You might think this was rather odd until she shared with others that buckwheat was not indigenous to Big Sur and that the White man brought it to plant on the steep cliffs to keep them from sliding into the ocean. The real kicker is that she had a real live Blue-Winged Butterfly living in her headpiece. So La Loca would often tell people she was being watched from outer space, thing is, she was telling the absolute truth, but because she was sworn to secrecy, people thought she was crazy. La Loca appeared to be replicating the human condition of those persons whose lives were exploited and/or oppressed. People who did not know her would see her in public places and speak quietly and conspiratorially, “There is that crazy lady from Big Sur; they say she spent the better part of her life in State hospitals.” In the minds of many, La Loca’s time in the State Hospital at Atascadero had transmogrified her. At the same time, many regional professionals spoke an unspeakable truth or that she had experienced a number of systemic mishaps in the bureaucracies of the courts and the asylum that labelled her nearly insane, and yet she wasn’t, but no one ever came to her defense for fear of not being up-to-date on the shared meanings of their profession. People kept their distance, stigmatizing and shaming her the way people do in daily life—they simply never got to know her. Any way you cut it, La Loca didn’t deserve to be placed in handcuffs and hauled out of court and taken to the State hospital like she was some kind of lunatic. If there is a rule, law or a moral code that she had broken, it may be that she grew marijuana on a small patch of land located on a U.S. Air Force Base located in the shallow woods in Big Sur. The reality about this is that most all of the locals did the same and so, too, did their descendants. La Loca just decided to grow her pot in a nice sunny mountain side where few people went not only because it was hard to get to, but because it was literally on a ten acre U.S. Air Force Base. You see, over the decades as Vanderburgh Air Force Base launched test missiles from its Southern California location, a professional military photographer would set the coordinates on cameras strategically placed at the ten acre base in Big Sur to measure the trajectory of test missiles. The location of the Big Sur site was not widely known because it was located on a small patch of land owned by the military sandwiched between the Little Sur Ranch and the Big Sur Ranch so people assumed it was on private property. In addition even though it wasn’t within their legal purview, there were ranch hand managers that used to escort people off these properties, plus there was a large intimidating sign that read, “Do Not Enter or You Will Be Shot at Your Own Expense.” No one believed La Loca about the existence of the U.S. Air Force Base even though a story about the photographer capturing some of the best UFO footage was printed in the special edition of LIFE magazine, “The Case for Interplanetary Saucers” (April 7, 1952) with a photo of La Loca’s idol, Marilyn Monroe, on the cover, and people said, La Loca was crazy.

|

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed