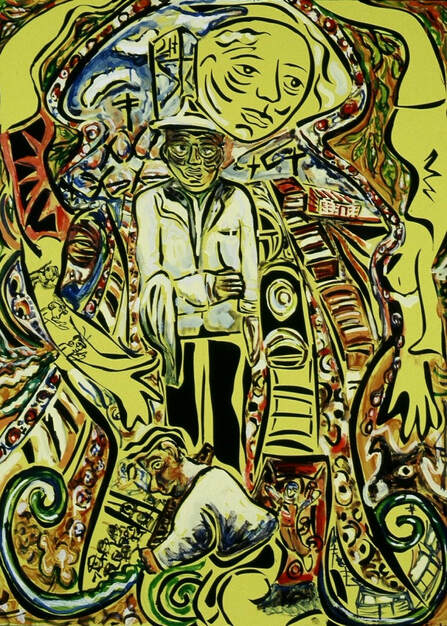

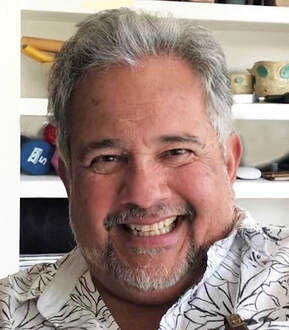

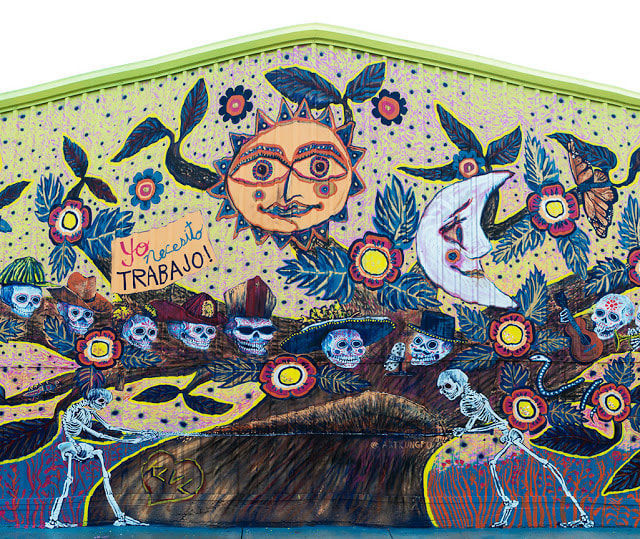

The Art of Jacinto Guevara: Documenting Unique Latino Cultureby Ricardo Romo First published in Ricardo Romo’s Blog, Latinos in America, November 19, 2021. Reprinted in La Prensa Texas, November 26, 2021. The seventies are remembered as a monumental decade for most Americans. In the early years of the decade President Richard Nixon’s resignation and the Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade dominated the news. Earth Day, Godfather movies, and disco music fascinated young people. The advent of the computer revolution marked a major change in society. For Latinos, the decade included significant events as cities across the Southwest experienced school walkouts, and California farmworkers won important union and legislative policy victories. Talented youth introduced Chicano poetry, plays, and film, and universities developed Chicano Studies classes and programs. Chicano artists who grew up during the seventies witnessed great transformations as they saw for the first time a flowering of their own artistic cultural creations. Jacinto Guevara of San Antonio emerged as one of the fortunate individuals who rode the early waves of this artistic movement. His story provides some important insights into one of the most significant eras of Chicano artistic creativity. From an early age Jacinto Guevara discovered that art represented an important means of communicating. Guevara came of age artistically during the early 1970s while attending Belmont High School in East Los Angeles. At the time, few Latinos went to museums but most grew up surrounded by commercial art, usually in the form of billboards and posters. Significantly the early expressions of Arte de La Raza appeared in public art. Chicano art originated with the mural movement in California. Art historians place the birth of Chicano art between 1968-1973. Guevara was a teenager when Chicano artists painted a mural at the headquarters of Cesar Chavez’ United Farm Workers Union in Del Rey, California. Some of the earliest Chicano murals originated in the heart of East Los Angeles, in close proximity to Guevara’s home. When Joe and John Gonzalez decided to convert an abandoned meat market into an art gallery, they recruited two future Chicano art stars, David Botello and their brother-in-law Ignacio Gomez, to paint what UCLA art historians have identified as the first public Chicano mural in East Los Angeles. Muralism became the most prominent creative development of Chicano art. Guevara enrolled at California State University Northridge [CSUN] in 1975, a time when colleges throughout Southern California were reaching out to East Los Angeles students. Guevara had seldom gone to the San Fernando Valley, home of the Northridge campus, but he liked CSUN’s Chicano Studies Program which was in its sixth year. He majored in Ethnic Studies and took classes with famed Chicano historian Dr. Rudy Acuña. Guevara loved music and joined the mariachi band headed by Professor Beto Ruiz. Guevara became a frequent art and cartoon contributor to El Popo, the Chicano student newspaper founded in 1970. After graduation from CSUN in 1980, Guevarra painted on a regular basis and also joined several musical bands. During these years, while Guevarra remained an early aficionado of the emerging Chicano murals in his community, he focused on his drawings and canvas painting. He bought one of his first canvases for three dollars and spent a half day cleaning it. Guevara worked at his art but could not seem to make the right connections to get his paintings in galleries and had a difficult time making a living as an artist. An invitation in 1990 by the established B-1 Galleries in Santa Monica offered him some hope. He was invited, along with several of the leading East Los Angeles artists, including Frank Romero, Wayle Alaniz, and Paul Botello to exhibit his paintings. Although Latino art was gaining in popularity, few of the paintings sold. After that show, Guevara began to think of leaving Los Angeles and was attracted to San Antonio because of the city’s thriving Chicano culture. Guevara found the San Antonio weather suitable for his preference of open air painting, or what the French called “plein air.” Some of his favorite subjects included abandoned railroad stations and warehouses. He delighted in finding unique subjects for his paintings, such as icons and buildings in San Antonio that most observers had overlooked. Many of his paintings reflect the older sections of the East and West side of town. He looked for old houses, residences that did not necessarily catch the public’s attention. These residential structures were simple, but attractive. He told me that these houses “weren’t necessarily pretty.” In 2016 Lewis Fisher published Saving San Antonio: The Preservation of a Heritage. It told a story of the San Antonio Conservation Society’s organized efforts to save historical houses from destruction. Guevara is also “saving San Antonio” through his paintings. His work captures the essence of the city, areas where not all the houses and buildings are spectacular, but they contain meaning and beauty for their owners. Guevara’s structural portraits, such as that of the 1880s building, “Liberty Bar,” which became a hangout for many Chicano artists, capture a heritage that makes San Antonio unique.  Ricardo Romo is an author, educator, and Latino Art connoisseur. He has degrees from the University of Texas at Austin (BA) and UCLA (PhD).

1 Comment

You may download a pdf of all three parts below.

Pandemic Exposes Widening Gaps for Latinos in Higher Education |

|||||||||||||||

| |

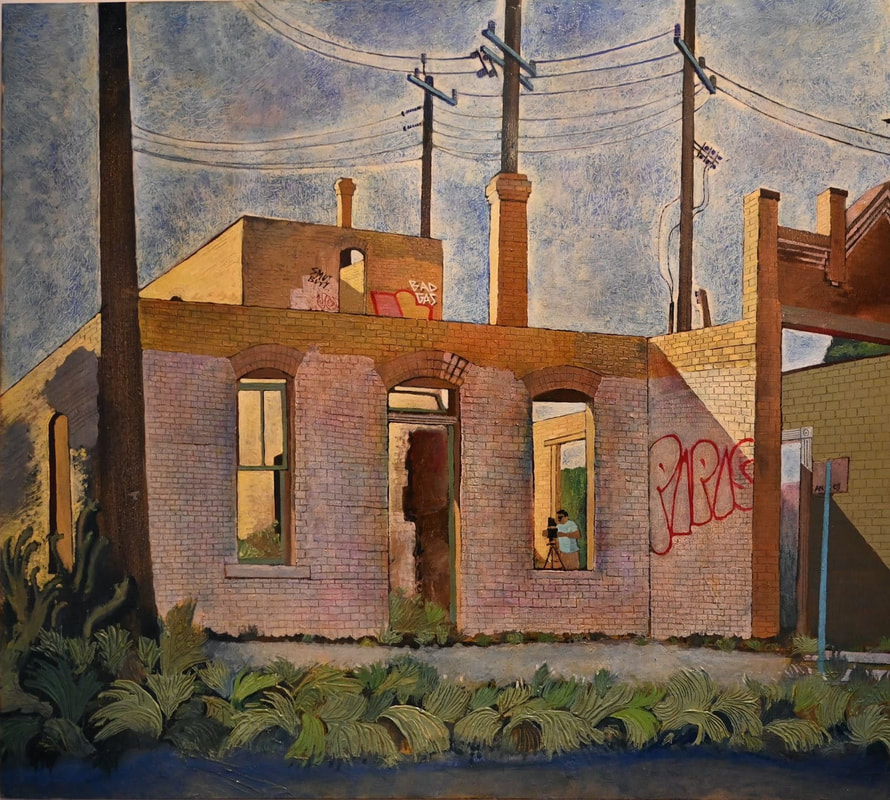

Marta has been working on a series of paintings of the San Antonio train yards near her childhood home. Through these paintings, she explores the role of trains in the Mexican migration through the Southern Pacific. Carpas, traveling circus and vaudeville troupes that performed throughout Mexico, are the inspiration for another series that has captivated Marta’s creative energies. Wings Press published a book on the collaborative suite of Carpa related serigraphs titled Transcendental Train Yards. The collaborative suite was created with Chicana poet and folklorist, Norma E. Cantú.

Her work is in the collections of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, The State Museum of Pennsylvania, The McNay Art Museum, The Fine Art Museum of St. Petersburg, Florida, and The National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago. Marta’s work is part of actor/director Cheech Marin’s extensive private collection of Chicano art. She participated in “Chicano Visions: American Painters on the Verge,” which traveled throughout the United States from 2001 to 2006, as well as Mr. Marin’s exhibition, “Chicanitas/size does not matter,” featuring small works from his collection. Marta’s public art commissions can be seen in the Philadelphia area at Simons Recreation Center, and The Children’s Hospital in Montgomery, Pennsylvania. The most recent sculptural works for the northern part of the City of Philadelphia is a series of 100 feet steel installations titled “Reclaiming Gurney Street. The piece was commissioned by the Hispanic Association of Contractors and Entrepreneurs to reclaim an opioid encampment to a public rails and trails project for the community.

| Retablo for Stan oil, enamel on aluminum, 3' x 3' 2014 www.artedemarta.com/paintings/retablo-for-stan2/ |

3' x 4' oil and enamel on metal

2002

www.artedemarta.com/home-2/trainyard-in-the-dayllight-copy/

oil and enamel painting on aluminum, 3' x 9′

Collection of the University of Texas in San Antonio

http://www.artedemarta.com/home-2/trainyard-in-the-dayllight-copy/

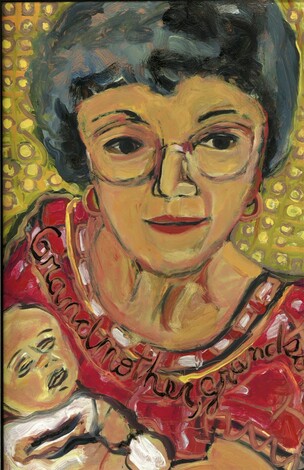

oil on copper, 18″ x 24″

1999

www.artedemarta.com/home-2/sm-grandmotehr-grandson/

enamel, oil on copper, 18″ x 24″

2004

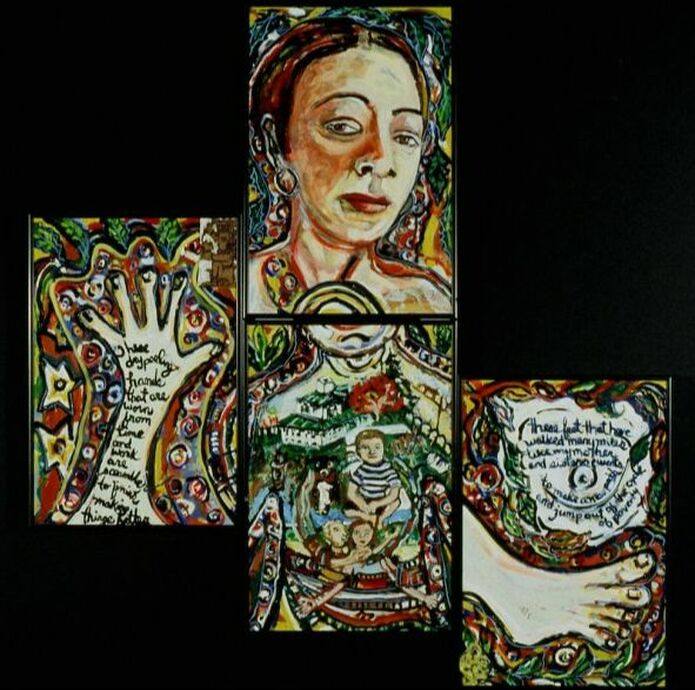

www.artedemarta.com/home-2/smfour-pieces-of-me-07-copy/

For more information on Transcendental Train yards, the suite and the book:

www.latinobookreview.com/norma-elia-cantu.html

Visit Wings Press to order a copy of Transcendental Train Yard, with art by Marta Sanchez and poetry by Norma E. Cantú:

www.ipgbook.com/transcendental-train-yard-products-9780916727970.php?page_id=21.

Also available on Amazon.

For a schedule of book signings and readings, please visit:

https://www.facebook.com/transcendentaltrainyard/

Learn more about The Philadelphia Art Alliance at:

https://philartalliance.wordpress.com/2015/10/30/sleepers-in-the-borderlands/

An Eye for

Community Art

Archives

June 2024

April 2024

February 2024

November 2023

October 2023

January 2023

December 2022

October 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

March 2022

February 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

June 2021

April 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

October 2019

August 2019

July 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

March 2017

December 2016

September 2016

September 2015

October 2013

February 2010

Categories

All

2018 WorldCon

American Indians

Anthology

Archive

A Writer's Life

Barrio

Beauty

Bilingüe

Bi Nacionalidad

Bi-nacionalidad

Border

Boricua

California

Calo

Cesar Chavez

Chicanismo

Chicano

Chicano Art

Chicano/a/x/e

Chicano Confidential

Chicano Literature

Chicano Movement

Chile

Christmas

Civil RIghts

Collective Memory

Colonialism

Column

Commentary

Creative Writing

Cuba

Cuban American

Cuento

Cultura

Culture

Current Events

Dominican American

Ecology

Editorial

Education

English

Español

Essay

Eulogy

Excerpt

Extrafiction

Extra Fiction

Family

Gangs

Gender

Global Warming

Guest Viewpoint

History

Holiday

Human Rights

Humor

Idenity

Identity

Immigration

Indigenous

Interview

La Frontera

Language

La Pluma Y El Corazón

Latin America

Latino Literature

Latino Sci-Fi

La Virgen De Guadalupe

Literary Press

Literatura

Low Rider

Maduros

Malinche

Memoir

Memoria

Mental Health

Mestizaje

Mexican American

Mexican Americans

Mexico

Migration

Movie

Murals

Music

Mythology

New Mexico

New Writer

Novel

Obituary

Our Other Voices

Peru/Peruvian Diaspora

Philosophy

Poesia

Poesia Politica

Poetry

Politics

Puerto Rican Diaspora

Puerto Rico

Race

Reprint

Review

Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales

Romance

Science

Sci Fi

Sci-Fi

Short Stories

Short Story

Social Justice

Social Psychology

Sonny Boy Arias

South America

South Texas

Spain

Spanish And English

Special Feature

Speculative Fiction

Tertullian’s Corner

Texas

To Tell The Whole Truth

Trauma

Treaty Of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Walt Whitman

War

Welcome To My Worlds

William Carlos Williams

Women

Writing

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed