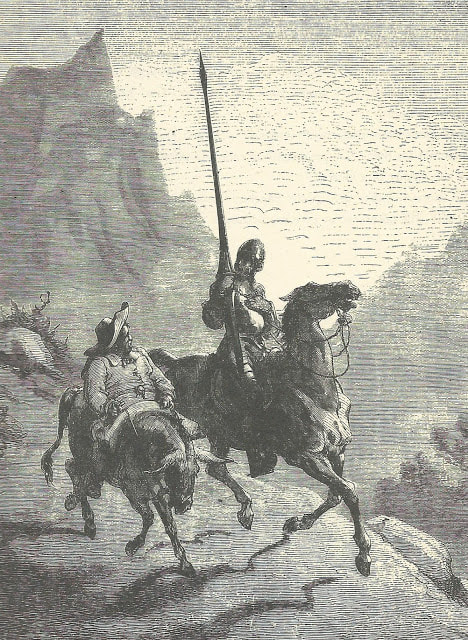

Tertullian’s CornerWe are all SanchoBy Rosa Martha Villarreal Sometimes clinical language cannot properly capture the essence of a thing. Edmund Husserl went through great lengths with his Philosophy of Phenomenology to define the relationship between consciousness and being, to capture the essence of a thing, or, in his words, to identify “the catness of a cat.” That Phenomenology is often studied along with literature is not surprising because there is no singular sound bite that can define what makes a work of fiction literature versus entertainment or agitprop. As to a definition of authentic literature, I have always looked to the canon and measured my own response as a reader and that of my students. My students remarked, “The stories we’ve read in your class are about me. It’s as though you knew what I was feeling when you chose those stories.” Through the years, many more told me, “When you talk about the themes in those stories, it’s as though you wrote those stories yourself! Like you are inside the writer’s mind.” My response: “That’s because those stories are also about me, about the secret person within.” Joseph Conrad’s secret sharer, T.S. Eliot’s true face behind the public “face to meet the faces that you meet.” That is the best definition I have of real literature: it is the story of the reader’s inner self disguised as fiction. It is a conversation between the author and the reader through metaphor, symbolism, and imagery. It suggests rather than tells, seduces rather that defines. It is the remembrance of the dream we had forgotten, and the realization of the forbidden secret. ***  The niece and housekeeper of Don Quixote bar Sancho Panza, "thou bundle of wickedness, and sackful of roguery," who comes to seek his island from the knight. p. 388 The niece and housekeeper of Don Quixote bar Sancho Panza, "thou bundle of wickedness, and sackful of roguery," who comes to seek his island from the knight. p. 388 DESIRE OVERWHELMS FACTS I have been revisiting the classic books in my collection. When one re-reads a great work, one always discovers something that one had missed the first time around or one of those instances when life imitates art. The book for me right now is Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’s Don Quixote de La Mancha. Reading Don Quixote in the Age of Trump and fake news’ attacks on reality, the character that stood out wasn’t the delusional knight but the hapless Sancho Panza. In Sancho I saw the pathos of what we today call “the low information voter,” the consumer of fake news and bizarre conspiracy theories. He is the person who follows the charismatic cult leader, believes the gifted politician, confuses the buffoon for a wise man. Anyone who purports to provide easy solutions to his afflictions. Sancho is the unemployed coal miner who cannot accept the empirical reality that clean energy is the future. Rather than adapt and learn new skills, the Sanchos of today wish to return to an imaginary green world, to the seduction of “bringing back coal jobs,” “getting our [sic] country back,” or “making America great again.” The past, Tsunetomo Yamamoto said, slowly dissolves and can never return, yet from the perspective of those who feel dispossessed, it is a dream “[d]evoutly to be wish'd” (Shakespeare). Sancho believes that there are still undiscovered countries where men of low status can attain land and riches by the boon of men of rank as many had done a century before with the discovery of America. The conquistadors (and, yes, they were my ancestors*), in exchange for their service to the king, were granted land and weapons and the authority to impose their will on the new continent and its people. Sancho wants his island. Likewise, the misguided American of today longs for the America of Manifest Destiny. Ronald Reagan, who began this backward-looking trajectory, said that he wanted to return the America of 1980 back to the time of his youth. Reagan was the wannabe fictional cowboy who could roam and impose his will with the power of the gun, laws, and institutions that supported the Jacksonian vision. People said of Reagan, “He made us feel good about ourselves.” Who, pray tell, is “us”? It certainly wasn’t the progressive class, environmentalists, nor the intelligentsia. Sancho blindly believes that Quixote has the ability to make a curative potion that will heal any ill and injury they incur on their misadventures. Even after Quixote vomits the potion into Sancho’s face, the latter still believes Quixote. In comparison, many Bernie Sanders supporters passionately believed Sanders’ promise of a “free” college education. Empirically, we know nothing is free. The money has to come from somewhere, and even raising taxes would never cover a free college education for everyone for unlimited time. College entrance would have to be tightened, unwittingly giving even more advantages to the “haves” who can pay for entrance exam preparation. Unlike today, where a student can take his/her time with the course work, time limits would have to be in place to prevent the proliferation of “professional students.” Again, this would hurt students from less advantaged backgrounds who need to work, or need additional time for remedial coursework. Desires have a way of clouding our ability to envision unintended consequences. The pathos of Sancho Panza is his eagerness for ignorance. Even after he receives beating after beating, one humiliation after another, he chooses to believe the outrageous fabrications of Quixote. Desire overwhelms facts—obvious, shameful facts like when Quixote proclaims that a flock of sheep is an army and stupidly attacks them only to receive a well-deserved beating from the shepherds. Even after each pummeling, the gentleman Quixote, a gifted talker, spins an alternate reality, “alternate facts” in today’s parlance. Cervantes says that “Sancho hung onto his (Quixote’s) words without uttering one” (172) and later praises Quixote as being “fitter to be a preacher than a knight-errant” (176). The comparable Sancho in our world is the hapless Trump supporter who stands to lose his Medicaid, his clean air, his national parks, among other things, but still remains firm in his hoped-for Trumpian dream. The dramatic irony of Don Quixote works because we have the distance of fiction to see the utter ridiculousness of Quixote’s imaginary quests. The darkside of Quixote is not so much his indulgence in his madness as much as the need to have a follower. Quixote wants to be watched, admired, praised. But the (mis)adventures of Quixote and Sancho are comical rather than evil, analogous to today’s Bigfoot “truthers,” who really do nothing more than engage in self-inflicted public humiliation. At worst, they may get shot by an angry property owner for trespassing or hurting livestock. Quixote is not Faulkner’s Sutpen nor Milton’s Satan, who like Trump, Kim Jong-un, and Hugo Chavez, loose their dark ambitions on their followers and enemies equally. These dark men crave attention and admiration to feed their own degenerate souls, caring nothing for their followers, giving them stones when they ask for bread. They return contempt and cruelty for loyalty and love. *** WE ARE ALL SANCHO We are all susceptible to the delusion of easy solutions, to the honeyed rhetoric that appeals to our emotions rather than our reason. We can all be seduced by an ideology, right or left, which purports to have all the answers. We can only avoid Sancho’s fate by being aware that, on some level, we are all Sancho, willing to believe nonsensical conspiracy theories such as that the World Trade Center attack was an inside job by the Bush Administration; or that Hillary Clinton was running a child porn ring out of a pizza restaurant. However, when confronted by facts and reality, people naturally resist contradictions to their worldviews, cherished beliefs, and desire for meaningfulness in the face of a perpetually changing world. This is where literary fiction exerts its power. Fiction is the metaphor, the mirror that strips away the mask. The function of true literature is to penetrate the human mind and its defenses, to sweetly force awareness as if in a dream. The Roman poet Horace, in Ars Poetica (Epistulas Ad Pisones), said it best:

Rosa Martha Villarreal, recently retired as an Adjunct Professor at Cosumnes River College in Sacramento, California, is author of several important novels including Doctor Magdalena, The Stillness of Love and Exile, and Chronicles of Air and Dreams. The name for her column, Tertullian’s Corner, comes, she says, from the time when liberal, i.e., free thinking, people were persecuted by the Catholic Church. So young men (and women) would gather in some corner of a monastery under the pretense of discussing the Church Father, Tertullian. Thus, the tertulia was born.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed