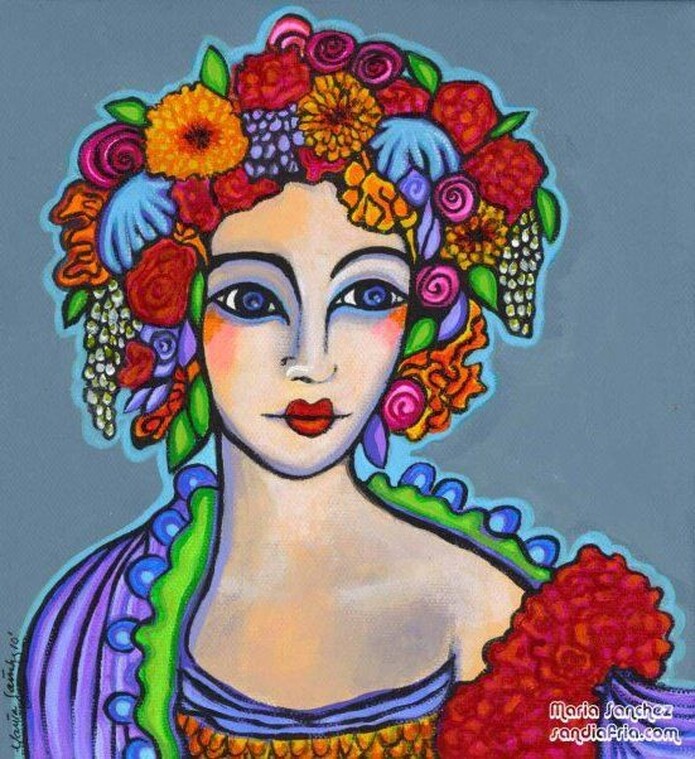

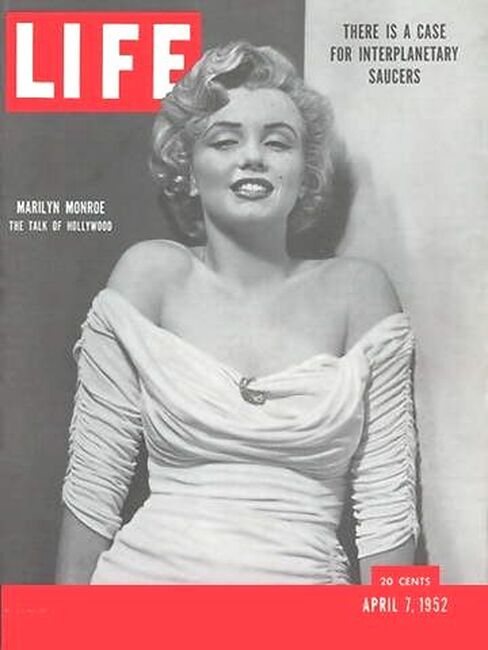

Chicano ConfidentialThe Unspeakable Truths about La LocaBy Sonny Boy Arias My morning started out just like any other early summer morning day along the Big Sur Coast, Califas. I drove down the hill to the market at the Big Sur River Inn to gas-up my VW Vanagon with two extra-large custom gas tanks. I was sure to clean the bugs off the windshield in order to enjoy the scenic route, arguably the most beautiful in the world. While my tanks were filling up, I walked into the Big Sur Market for a Grab-and-Go egg burrito made con mucho amor (with love) by Maria who rolls up gordita tortillas like my Nanita used to make to include a dash of green chile and a cup of fresh hot café de la olla. It’s a breakfast made for stone-cold Chicanos – priceless. Add to this a little touch of Los Lobos’ hit song Maricela, played over my Blaupunkt German-made speakers (with a lot of bass bottom just like the low-riders love and why the Germans love low-riders) and you realize that life doesn’t get much better – and then as if without notice, it does, life gets better, Chicano life suddenly gets better. Once the gas pump reached $100 on the first tank, I had to close it and open up the pump for the additional gas tank that would most likely take another $100. As I reached over to line-up my favorite music CDs, Los Lobos, Santana, Ozomatli, and Los Lonely Boys, I noticed the Chicano Batman CD was missing – it is probably stuck somewhere between the seats – somehow the order of the songs contributed to the momentum at which I ate the burrito and sipped the coffee, you must know what I mean, the same thing happens when eating a chorizo burrito while trying to balance your hot cafecito. Above the early morning chattering of the local Surf Bird, Barn Owls and Rock Doves I could hear singing on the other side of the gas pump. I had never heard such loud singing while filling up my gas tanks. It was difficult to decipher the singing on the other side of the gas pump because I was focused on the video feed running a story about a 65 year-old guy who was just eaten by a shark. The guy was only sixty yards off the coast at Ka’anapali Beach in Maui, the same stretch of beach where I introduced swim fins and open-ocean swimming to my 6 year-old grandson when he took off like a fish. The 65 year-old was on the first week of his retirement and the last day of his vacation, and that morning had turned to his wife, stating, “Honey, I am going on my last morning swim;” boy, did he get that right. As the singing on the other side of the pump got louder, it also got better so curiouser and curiouser I became. The singer on the other side of the gas pump was a young woman known to many as “La Loca.” She reached out to me as if it were a personal matter, “I just watched my favorite Mexican show, Tengo Talento, and have become very inspired to sing again!!” she said and then she adds, “This 17 year-old girl, Rosa Rochín, kicks some serious ass and so does her famous grandfather Buenaventura Rochin-Diazsalcedo! I think these are my people because they are very tall Mexicans, like me, from Guimichil, Sinaloa. Historically, my people were runners, they used to run messages between towns out in the middle of the desert, maybe that’s why I am so tall, and also a marathon runner.” Pointing to her tan muscular thighs, she adds, “Look at these legs; these are goddam long legs made for running. I have to buy jeans with leg sizes from 37 to 38 inches in length, that’s goddam long for a Chicana. I run the Big Sur Marathon every year!” While I glanced over at the rapidly spinning numbers on the face of the gas pump nearly reaching another 100.000, La Loca starts singing again and the amount on my meter catches her eye; she then tells me, “Man, you have to start singing to the gasoline.” I thought, “What the …?” and all at once, as she turned off the video feed on my gas pump, blurts out, “Hey vato, I said you need to sing to the gas, that way you will get better mileage” and she said it again, “Sing to the fucking gas and you will get better mileage.” All at once, she seemed like the type of person that not only demands sudden attention but that also raises all the spirits of everyone she is around. Today was her birthday, she asserted, “I was born on the same day as JFK, John Fitzgerald Kennedy!” Now, I thought, “That’s interesting!” and replied “I was born on the same day as St. Paul the Apostle.” I made sure to point this out because I always feel like I don’t get any respect the same way St. Paul did or Rodney Dangerfield or Aretha Franklin, so like St. Paul I have struggled with this my whole life. If you never met La Loca she was a sight to be seen for sure; she wore unbelievably beautiful headpieces that must have been influenced by her Esalen Indian and Mexican background and her great grandfather to be sure – as you got to know her you could see a vibrant and odd beauty rarely found. At first you might look at her and think, “There is something about this young lady that I find very attractive,” but you can’t put your finger on it, and then you zero in on her head piece and find that you can’t take your eyes off of it; plus it causes deep reflection when she leaves. It seemed that the locals know her and her family, but I did not; somehow in all the moving and grooving I do in both Northern and Southern Big Sur I missed meeting her. I soon found out why. I never really gave much thought to why locals called her, “La Loca,” that is, until my neighbor on Parrington Ridge (the one who boasts about living behind seven locked gates), told me that when La Loca was a teenager she had a “nervous breakdown” in the Monterey County Courthouse when her great grandfather was presenting his case about his land to a judge. The case surrounded the fact that her great grandfather had built a house years ago on a cliff in Big Sur without a permit. He had been there for so many years that everyone assumed he owned the land and had a permit, but he did not. La Loca and her parents had been raised on the property in question, so again, no one ever bothered to ask about a permit until now. You see, her great grandfather, an Esalen Indian, showed up in court with a beautiful hundred year-old head dress trying to make a case for obtaining a permit to extend his log cabin on the cliff. He had heard during the fire of 2016 that this was the right thing to do, but again, the reality was that he didn’t own the land in the first place, so in the eyes of the California Coastal Commission they could not legally approve a permit. When the judge as well as several commissioners made this clear, in their shitty way, while both disrespecting and speaking down to La Loca’s great grandfather, she lost it and became immediately incensed. La Loca’s great grandfather, grandfather, father, mother and extended family all became confused because again, they all assumed he owned the land. It was, to say the least, devastating to the entire family as well as to their friends and other supporters – There must have been 300 supporters in the courthouse that day. Great grandpa didn’t really know what the big deal was. Great grandpa’s supporters felt the commissioners were flexing their muscles and wanted to use him as an example to show the locals of Big Sur that they all had to have permits in order to, not only hold onto their homes but also to add on to them as well. Plus the insurance companies were now requiring proof of ownership (this all started following the 2016 fire) or they would not be insured. During the court case, La Loca had just started taking Chicano Studies classes at the Monterey Peninsula College, while at the same time working as a grounds keeper at the Esalen Institute. In both of these settings she learned that land had been taken from Mexicans in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (signed in nearby Old Town Monterey) and from the Esalen Native Americans in Big Sur. As a direct result, she became obsessed with the idea and on the day her great grandfather showed up at the Monterey Courthouse, she made this connection to her biographical past, so she blew a gasket, but she most certainly did not have a “nervous breakdown” the way it was depicted. Moreover, she was really pissed-off, but there is a major difference. La Loca showed up in court that day in one of her elaborate headpieces and began pointing to flowers on her head as symbolic examples and case studies in support of the idea that her great grandfather should be approved for a permit. Her headpiece was an excellent symbolic gesture of visual and public political art. Nay-sayers said she was “crazy” and that she was having a “nervous breakdown.” In his capacity as a local from Big Sur, the judge knew this was not the case, and so, too, did the commissioners, but no one came to her defense because the unspeakable truth was that just about everyone in the courtroom that day was breaking the law or out of compliance in the same way as her great grandfather. It was common knowledge that most people did not have permits for their homes no one had ever bothered to ask. Many locals are in fact, living on land they had never purchased, nor had acquired a permit to build onto their homes as evidenced by the insurance companies that decided not to re-insure Big Sur homes following the fire of 2016. During the course of the hearing, La Loca kept repeating Rudy Acuna’s concept of “occupation” to the judge. At one point she was screaming at the top of her lungs while in the courtroom “What is so different in our peoples squatting on the land than what the White man did in occupying our land. What is so fucking different!?” (See Rudolfo Acuna’s epic book, Occupied America.) As the judge shouted, “Order in the court, order in the court!!!” he slammed his gavel down with enough force to ring the bell at the strong man tower at a local circus; it was self-evident that he was doing the wrong thing. The judge was using the full force of his office, as well as that of the California Coastal Commission to sell out La Loca as well as all of the people of Big Sur, especially the Esalen people of which the judge’s DNA proved to be similar; everyone knew it, but he acted like a judge with his hands tied. “The law is the law!” just like Fidel Castro as he single-handedly murdered hundreds of Cubans with a shot to their heads as they were caught trying to leave the Island of Cuba. “The law is the law!” he uttered while pulling the trigger. Things got heated so quickly in the courthouse that day, emotions were flying in every direction. “Young lady, I am holding you in contempt of court!” said the judge and he ordered the county sheriffs to “take her away.” As they struggled with La Loca it was evident that she was strong both physically and mentally as it took three obese Latino sheriffs to take her down to the floor and handcuff her. As they did, she yelled out, “I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept…” [Angela Y. Davis.] After this episode, the locals in Big Sur resented the judge’s actions to the extent that he was soon voted out and so, too, were the assemblyman, congressman and senator, all representatives of Big Sur. The unspeakable truth was that everyone in the courtroom that day could have been charged with not having a permit to build or expand their homes. Everyone knew it, but no one dared mention it. La Loca became the scapegoat and was sentenced to four years in the Atascadero State Hospital for men, that’s right for men, as the judge must have screwed up the paper work. As a result, for many years La Loca was nowhere to be seen; she could not be found anywhere along the steep cliffs or singing dying whales or walking with the condors on the beach, not even singing to the gasoline pumps, as she had been officially assessed as “mentally ill” and put away in the State hospital. Several years later when she was released, she pulled out her old camera and began talking pictures along the coastline near Bixby Bridge just as she had done before being committed. In so doing, she found a white and blue hardhat that read “CalTrans,” so she put it on. Within just a few minutes, a CalTrans truck pulled up beside her and inquired about both her activities and the hat. They ordered her off the property where she was taking pictures and she must have given them the look because as she reported, “They became very stern” but when she opened up, once she shared her story they realized whom they were talking to and felt empathy for her. The two men, one from CalTrans and another from NASA started by giving her the hardhat, followed by a rationale for why she needed to get off the property. They went on to gain her trust by sharing a story that she could never share with others. The guy from CalTrans said they had planted several hundred acres of buckwheat plants on the steep cliffs in order to keep the cliffs from sliding into the ocean. And the guy from NASA said that the buckwheat attracted the blue-winged butterfly and that they were performing top secret research on how to spot the butterfly from outer space. It’s true!  (Source: ANU Open Source image: http://www.photonicsviews.com/butterfly-wings-open-door-to-new-solar-cells/) (Source: ANU Open Source image: http://www.photonicsviews.com/butterfly-wings-open-door-to-new-solar-cells/) In a confidential report to NASA, Lead Researcher Niraj Lal from the ANU Research School of Engineering, said, “Engineers have invented tiny structures inspired by butterfly wings that open the door to new solar cell technologies and other applications requiring precise manipulation of light. The inspiration comes from the blue Morpho Didius butterfly, which has wings with tiny cone-shaped nanostructures that scatter light to create a striking blue iridescence, and could lead to other innovations such as stealth and architectural applications.” In the manner of public protest, La Loca wore a sizeable piece of a buckwheat plant in her headpiece. You might think this was rather odd until she shared with others that buckwheat was not indigenous to Big Sur and that the White man brought it to plant on the steep cliffs to keep them from sliding into the ocean. The real kicker is that she had a real live Blue-Winged Butterfly living in her headpiece. So La Loca would often tell people she was being watched from outer space, thing is, she was telling the absolute truth, but because she was sworn to secrecy, people thought she was crazy. La Loca appeared to be replicating the human condition of those persons whose lives were exploited and/or oppressed. People who did not know her would see her in public places and speak quietly and conspiratorially, “There is that crazy lady from Big Sur; they say she spent the better part of her life in State hospitals.” In the minds of many, La Loca’s time in the State Hospital at Atascadero had transmogrified her. At the same time, many regional professionals spoke an unspeakable truth or that she had experienced a number of systemic mishaps in the bureaucracies of the courts and the asylum that labelled her nearly insane, and yet she wasn’t, but no one ever came to her defense for fear of not being up-to-date on the shared meanings of their profession. People kept their distance, stigmatizing and shaming her the way people do in daily life—they simply never got to know her. Any way you cut it, La Loca didn’t deserve to be placed in handcuffs and hauled out of court and taken to the State hospital like she was some kind of lunatic. If there is a rule, law or a moral code that she had broken, it may be that she grew marijuana on a small patch of land located on a U.S. Air Force Base located in the shallow woods in Big Sur. The reality about this is that most all of the locals did the same and so, too, did their descendants. La Loca just decided to grow her pot in a nice sunny mountain side where few people went not only because it was hard to get to, but because it was literally on a ten acre U.S. Air Force Base. You see, over the decades as Vanderburgh Air Force Base launched test missiles from its Southern California location, a professional military photographer would set the coordinates on cameras strategically placed at the ten acre base in Big Sur to measure the trajectory of test missiles. The location of the Big Sur site was not widely known because it was located on a small patch of land owned by the military sandwiched between the Little Sur Ranch and the Big Sur Ranch so people assumed it was on private property. In addition even though it wasn’t within their legal purview, there were ranch hand managers that used to escort people off these properties, plus there was a large intimidating sign that read, “Do Not Enter or You Will Be Shot at Your Own Expense.” No one believed La Loca about the existence of the U.S. Air Force Base even though a story about the photographer capturing some of the best UFO footage was printed in the special edition of LIFE magazine, “The Case for Interplanetary Saucers” (April 7, 1952) with a photo of La Loca’s idol, Marilyn Monroe, on the cover, and people said, La Loca was crazy.

0 Comments

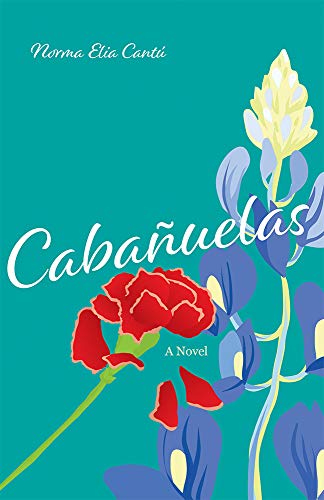

A Book Review of Cabañuelas, a novel by Norma Elia Cantú By Rosa Martha Villarreal Dr. Norma E. Cantu describes her fiction as “creative autobiographic ethnography.” Judging from the blurbs on the cover of Cabañuelas and other commentary about her earlier book, Canícula, the post-modern aspects of the novel will be analyzed in full detail: it’s fusion of various genres, including the scholarly and biography; it’s use of photography as a narrative tool; it’s a deeply personal portrayal of family and hearth; the descriptions of Spain’s festivals; and finally, its use of narrative as political discourse. But Cabañuelas is more than that. More than a romance; more than an ethnographic journey; more than one Chicana’s search for the ancient roots of her Mexican-Tejana culture. In this novel, the word “cabañuelas” alludes to a rediscovery of the most ancient knowledge of human passions and aspirations. Technically, the cabañuelas are a system of weather prediction, a lost art, a knowledge discarded by the science of meteorology and dismissed as superstition. But what we have discovered in our post-modern era is that beneath the surface of these so-called folk practices and superstitions are a kernel of the authentic human landscape of passion and experience, a form of knowledge found only in the language of dreams. Thus, the cabañuelas are a metaphor for the existential journey of the protagonist, Nena. Once she makes the decision to search for the ancient origins of her culture’s festivals in Spain, her spiritual calendar has been marked, and a destiny gets set in motion. The journey transcends from ethnography to the phenomenological discovery of the secret self, the self that is not a creature of human constructs but of nature and God. Even before Nena Cantu departs for Madrid on a Fulbright Fellowship, she longingly reflects on her family, her homeland, and its rituals. Thus, nostalgia commences her spiritual cabañuela. Her nostalgia for the origins of these rituals is what inspires her research. Her arrival in Spain is reminiscent of every Hispanic’s first experience: Spain is simultaneously foreign but familial. You are not a Spaniard, but idioms aside, you speak the same language and are shaped by the sensibility of that language. You are a continuation of a mestizaje that began in antiquity when the Romans conquered the Iberian Celts, and continued with the subsequent conquests of Germanic tribes, and finally the Moors. It isn’t long before Nena decides that to find the true origins of the festivals, she must not merely study them in the ancient texts but go and experience them first hand throughout Spain. It is in these journeys that she crosses over from the world we perceive to the world as it really is. That other world, exiled to the margins by our constructs of reason and morality, where there is also truth and beauty, and perhaps the nexus to a spiritual world. The festivals are the relics of the ancient dramas of collective awareness of an invisible universe. It is in that landscape of festivals and timelessness that Nena finds a love that cannot be explained, only experienced. Love before Logos, reason, history, and politics. It is the descent into the body of another who is not only meant for us, but has authored the secrets of our psyche. Someone only you can recognize because you understand in that other language that he is the door to your secret self, to your other self behind the mask of the face that meets the faces that you meet, as T.S. Eliot said. “That’s him?” One of Nena’s friends asks incredulously years after she returns to Madrid. When a Chicana polemicist reminds Nena that he is a member of the conquering race, Nena thinks, but he is human. And that is it: The greater truth. Before we were all else, we were an animal like the rest until we discovered a world beyond. The birth of higher consciousness set us on a separate destiny: the spiritual, and the discovery that the passion of the flesh with one other human would unite us with the spiritual. Passion and spirituality are the same, Sor Juana de la Cruz said. Not the mere sexual release and innate drive to reproduce encoded by evolution; not the patriarchal version of marriage, where women’s aspiration are oppressed in the name of societal good. Something so old we cannot not quantify it but know it is real because we feel it; the knowledge of the flesh and the semiotic language of dreams and intuition. “Before God was love,” said D.H. Lawrence. Nena’s cabañuelas creates her destiny, and Paco is part of that destiny. But so is return. The destiny was set in motion by the nostalgia for the origins of her cultural self. It must be, then, that she’d return although the love she found was profound, magical in the pre-modern definition of magical. That love could have only been discovered in a temporal space. It is a hard thing to realize that a powerful human connection such as hers and Paco’s does not mean it translates to a life together, to “live happily ever after” although that is also a possibility depending on the couple. Paco expects her to sacrifice her homeland for him, but does not offer to do the same. She would have to give up the very thing that started her journey in the first place. Regardless, despite her returning to Texas, the love never ends. It is untouched by time and never replaced by other lovers. My grandfather José used to love a song that was already old when he was born. Un Viejo amor, ni se olvida ni se deja. Never were wiser words spoken. Ultimately, despite the fusion of various genres, its ethnographic contribution, this novel is also about a woman’s existential search where she repeats the ancient, archetypical journey. She sets out to find her cultural identity and finds her ancient human identity. If there is a succinct image for that, it is her self-portrait, the artist, half-hidden behind the camera lens, at once concealed and revealed. Read an excerpt from Cabañuelas: A Novel by Norma Elia Cantú (University of New Mexico Press, 2019) on Somos en escrito under the title, “The women take over the town for a day” (https://somosenescrito.weebly.com/fiction-ficcioacuten). The book is available through the University of New Mexico Press (https://unmpress.com/books/cabanuelas/9780826360618) and on Amazon. .  Norma Elia Cantú, author of Cabañuelas: A Novel, is the Norine R. and T. Frank Murchison Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas. Her recent works include Transcendental Train Yard: A Collaborative Suite of Serigraphs, Canícula: Snapshots of a Girlhood en la Frontera, Updated Edition (UNM Press), and the coedited anthology Entre Guadalupe y Malinche: Tejanas in Literature and Art.  Rosa Martha Villarreal, a Chicana novelist and essayist, is a descendant of the 16th century Spanish and Tlaxcatecan settlers of Nuevo Leon, Mexico. She drew upon her family history in her critically acclaimed novels Doctor Magdalena, Chronicles of Air and Dreams: A Novel of Mexico,and The Stillness of Love and Exile, the latter a recipient of the Josephine Miles PEN Literary Award and a Silver Medalist in the Independent Publishers Book Award (2008). She writes a column, “Tertullian’s Corner,” for Somos en escrito Magazine. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed