“Piano”by Linda Zamora Lucero Papa’s funeral, spring 2009. In the tiny chapel are my sister Ellie and her clan from Phoenix, my brother Tito, both of Tito’s ex-wives, and Papa’s best buddies—Montez leaning on his cane, Garcia in his wheelchair, reeking of cigar—both retired welders from Hunters Point shipyard. Papa radiated so much love even my newly ex-boyfriend Julián shows his face to pay final respects. Only Mama is missing. When Tito went to pick her up, she insisted she was too distraught to come. Great, I think, although I don’t believe it for a second. Sure enough, just as the service begins, she materializes in the middle of “Gracias a la vida” in a red coat and yellow hat with feathers. “I don’t need help to sit down!” Mama says, slapping the usher’s hand away. “You’re late,” I whisper, grudgingly making room for her in the pew. Dressed up for Papa, I’m wearing a fitted black dress with tiny hand-sewn turquoise flowers, a Oaxacan shawl, large hammered gold hoops, black hair pinned up. “Hello, Raquel,” Mama says pleasantly, sitting on the fringe of my shawl. “Such beautiful music.” And she commences to hum along with the vocalist. Yanking the shawl loose, I close my eyes and pretend she isn’t there. **** After the service, our family gathers at Tito’s house, where we wolf down plates of homemade chile verde, throw back shots of Herradura and recount the same cherished stories we always do whenever we get together. A favorite is how one Thanksgiving—this was before Mama abandoned us—we children were squabbling over the drumsticks—and Papa asked if he could just this once have some peace around the table. Seven-year-old Tito, thinking he was being real hilarious, smugly handed Papa the bowl of peas, whereupon Papa angrily slammed his fork on the table. We watched in horror as the fork slowly became airborne and cracked the kitchen window. We ate in chilly silence until the pumpkin pie with whipped cream made us boisterously happy again. Tito says, “’Member?” We laugh at the timeworn anecdotes, fall silent with grief. At the ripe age of thirty-nine, Ellie gets up to dance, leading us in a raucous chorus of “Papa Was a Rolling Stone.” Missing Papa’s delighted belly laugh at his youngest daughter’s antics, I suppress a shuddering sob. Ellie’s kids bickering over a toy feels like the saddest thing in the world. Tito brings Mama a cup of té manzanilla and fusses over her. She eyes the proceedings from a corner armchair, the feathered hat like some ridiculous canary atop her head. She’s on her best behavior. Of course, it doesn’t last. Barely three weeks pass before the director of the Thirtieth Street Senior Center calls me at Galería Libertad, the community art center I direct, asking to meet with Mama’s family, meaning Tito and me, since Ellie is safely back in Phoenix. Thirtieth Street is where Mama eats lunch on weekdays, takes piano classes, and is an active member of Mr. Topper’s Mission Tappers, no tapper under seventy-five. Before he died, Papa spent his Saturdays playing poker at Thirtieth Street. “I realize this is a difficult time, so I do apologize,” Mrs. Whitmark says, her lipstick pomegranate pink. She pauses, looks up through bifocals, and an all too familiar despair washes over me. To most people, Mama is an eccentric elder with a mind of her own. Some of us know otherwise. “Mrs. Flores is accusing people of stealing from her purse. Everyone is suspect—the other seniors, the janitors, the cooks, even myself. It’s quite upsetting. Your father helped calm her whenever she got this way, and now we need her family to step in.” “Of course,” Tito says, nodding. “We’ll talk with her.” Tito is a machinist for the transit system. He’s completely overbearing, but somehow women find him fascinating. He’s been married twice with no children, while I can’t seem to find my match, romantically-speaking. Tito has no idea what I do at Galería Libertad. He teases me by introducing me to his friends as “my sister, the starving artist,” and he’s not far wrong. But in the Mission arts community, I have found friendship, love, sustenance. My home. “Losing Dad hasn’t been easy for Mom,” Tito continues. I love my brother, but when it comes to Mama, he ticks me off. “She’s crazy,” I say flatly, brushing a strand of hair from my eye. After Papa’s funeral I’d shorn my long hair into an asymmetrical what-I-hoped-was-stylish cut. Tito shoots me a foul look. But crazy explained my mother who, one ordinary morning after Papa had gone to work, made us children breakfast and sent us off to school, then took a train back to her hometown in New Mexico. To stay. Tito was ten; Ellie, six. I was twelve. In the chaos that followed we all pitched in to help Papa with shopping, cooking and housekeeping. That was the easy part. After Mama left, Ellie suffered from debilitating headaches and Tito was suspended from school every other week for one thing or another. Papa began drinking heavily. There was no one to turn to. My parents had grown up in New Mexico, but we were born and raised in San Francisco in four rooms on Shotwell Street, miles away from kinfolk who gossiped about the neighbors, shushed children at weddings and offered solace when worlds shattered. I was raw with anger at Mama, praying that she’d return to us, declaring that she wouldn’t dare. “Maybe,” my best friend Anna said, “she ran off with a lover.” Prone to dramatic flights of fancy, Anna with her black cat’s-eye glasses concocted wildly romantic stories about our favorite middle school teachers. Now she had one for my mother. Maybe you can just shut up,” I said. A weak response, but heartfelt. Crazy explained Mama’s sudden reappearance in San Francisco five years later. That was the first time a social worker told us Mama was “mentally and emotionally unstable.” But I knew he meant crazy, and for that I was grateful. It explained her crying jags, her periodic paranoia, her denials that she needed help, her refusal to take prescribed medication. Crazy summed it up. In Mrs. Whitmark’s office, Tito loudly clears his throat and promises that he will get Mama to take her meds. “Good luck,” I say, grabbing my daypack. Tito is uncharacteristically silent as we leave Thirtieth Street, his broad, good-natured face splotchy. As soon as we reach my beat-up Toyota, he lets loose. “You were out of line, Rocky, calling Mom crazy! She’s our mother!” Tito and Mama wrote each other regularly after she left. She worked in a café near Taos, and, as we found out later, had reconnected with a high school flame. I was horrified. Tito and Ellie visited her summers, but I refused. When Mama returned, my siblings were elated, being younger and obviously needier than I was. In the five years she’d been gone, I had become 100% Papa’s girl, Athena sprung from Zeus’s head, full grown and battle-ready. Papa never dissed her, but I held her responsible for his alcoholism, his melancholy, for all of us having had to answer endless questions from teachers, busybody neighbors, and shitty strangers who felt sorry for us. Because what’s more pitiful than motherless children in a strange land? So when Tito says, “She’s our mother,” I say, “You’re entitled to your opinion, Tito. I have to go. We have an exhibit of Cuban posters opening in a week.” “Weird haircut,” he snorts. He gets into his car and peels out, as if he were sixteen instead of forty-one. I burst out laughing as his Midnight Blue Chevy leaves fat skid marks on the asphalt. The next time I see Tito, I’ll ask about his prize roses. We Flores don’t say Sorry, even when it’s called for, or a straight-out up-front I love you, even though we do. After an argument, when one of us asks about the weather, it means I’m over it. Dancing salsa after a backyard barbeque means I love my family, or I love the whole fucking world and everything in it. Things go unsaid for days, even years, the love, anger or sorrow pent up inside like a great accumulation of molten lava below surface, wanting release. It’s the Flores way. Friday evening, I’m at home on the computer, writing wall text for the exhibit, half listening to Jeopardy. The category is “Shakespeare,” the answer is “Doubtful Dane.” My cell buzzes—Ellie in Phoenix. I ignore it. We used to watch Jeopardy, Papa and me. He admired Alex Trebek. Debonaire, brainy and not above showing it. A contestant hits her buzzer and shouts “Who is Hamlet?” On Ellie’s third call, I answer, muting the TV. “Mom’s not answering her phone,” my sister says. “I wasn’t answering my phone either,” I chuckle. Ellie ignores me. “Mom was perfectly fine yesterday—Tito says she’s taking her meds, but now I’m worried.” Usually, Ellie asks about what’s happening at the Galería, or about my mostly pathetic, sometimes hilarious dating forays in the six months since I broke up with Julián. Not this time. “Have you seen Mom since the funeral?” On television, Alex Trebek’s lips announce Final Jeopardy, inspiring looks of consternation in the contestants. The category is “San Antonio, Texas.” “Remember the Alamo?” I ask Ellie, wishing she didn’t live so far away. I miss our sisterly heart-to-hearts over her homemade biscochitos and wine. “Come on, Rocky, would you just get over there and check on how she’s doing? Tito’s in L.A. this week.” I sigh loudly, meaning yes. “Great! Love you!” she says, and hangs up. And the burden shifts to me. Mama lives in the same paint-peeling, rent-controlled Edwardian flat we were raised in, located in the heart of the Mission—what the realtors gleefully call “a neighborhood in transition.” No doubt. Since 1492. The door cracks open. “Hi.” I slide my foot inside before Mama can decide whether or not she wants a visitor. “It's me, your daughter.” “I know.” Hazel eyes peer up at me through huge red eyeglass frames. Mama is queen of her private little planet. She’s wearing a crimson apron with gold rickrack trim over a blue sweater shot with silver on top of a fuchsia dress. Purple leggings, lambswool slippers and a silver “Hottie” pendant complete the look. We are nothing alike. Born in the history-rich Abiquiú, New Mexico, Mama grew up speaking Spanish but she looks like a gringa with pale skin, auburn hair, light eyes like a wary cat. I’m dark like Papa, and proud of it. His first language was also Spanish, but his maternal grandparents were Taos Pueblo. I dress in black: turtleneck, jeans, boots. I do rock the earrings, however; the showier, the better. Today’s earrings are humongous crimson Lucite hearts, a gift from a Oaxacan artist. “What happened to your hair?” Mama says. “Why don’t you answer your phone?” I counter. The flat smells of Papa’s Tiger Balm and tobacco. I have to stop and catch my breath. “What’s wrong with you, fighting with me already?” Mama looks down the street before closing the door. “I thought you were someone else.” Her tone sweetens. “How are you, anyway, Raquel?” An ordinary question in an affectionately maternal voice, perfectly calculated to derail me. She does this every so often, and when she does, my heart flips like a kite in high wind, and I wonder what it would be like to have a real mother. Would we go to museums together? Would we shop for shoes, get our nails done? What do regular mothers and daughters do? The question slams into me whenever I run into girlfriends with moms, enjoying themselves. Mama hadn’t been there to help me buy my first bra or see me win first prize in a high school art contest. There was more I’d missed, things more profound. I just didn’t know what. The hallway is piled with boxes. “What’s this?” I ask. “I called Goodwill, but they’ve gotten choosy…your father kept everything: clothes, magazines, rusty tools.” A wave of fear hits me. “Goodwill? Where’s his brown suitcase?” Blood thunders in my ears. I catch a glimpse of myself in the hallway mirror. I look exactly the way I feel, bug-eyed and off-kilter. “There’s more in the garage. Not interested in old junk. Old junk, old men, old ideas.” Mama laughs, apparently delighted with herself. Old junk? “Please, please, don’t give anything away! I’ll get Tito to bring his pickup next weekend and we’ll take it all.” She disappears into the front room where the furniture—sofa, coffee table, Papa’s La-Z-Boy—has been moved against the walls. She pulls aside the lace curtains on the bay windows and looks out to the quiet street. “The piano should be here by now.” “Piano?” She doesn’t need a piano. Tito gave her an electric keyboard on one of her birthdays. It’s programmable, so that she can play tango, classical or her pop favorites. Papa would read his detective novels in his recliner, foot tapping while she plinked out Beatles tunes note by note. I never understood why he took her back. “Respect your mama,” Papa admonished me when I gave her attitude. “No matter what, she is your mother.” Respecting Papa, I shrugged. I was seventeen when she returned to Shotwell Street, my eyes were already focused on college and the wider world. Turning from the window, Mama says, “Can I borrow ten dollars until Friday?” I dig into my bag and hand her a ten and a twenty. “Just keep it.” I feel vaguely virtuous, giving her something without begrudging it. “I said borrow, Raquel, and only ten until Friday when my social security arrives.” The folded bill disappears into her apron pocket. “Whatever. I’ll have some water and then I’m out of here.” Running the faucet in the kitchen, I check for signs to report to Ellie. Cereal bowl in sink, oatmeal encrusted. Golden moth orchids I’d bought for Papa at the Alemany Farmer’s Market, shriveled and fallen onto the windowsill like exploded firecrackers. Portrait of the recently-elected President Obama. Wall calendar from La Palma Mexicatessen, inked Xs marking the days. Today is April 6. No X as yet. Mama is right on my tail. “I pay my debts. I’m not like that Julián of yours. He still owes me money.” Here we go. “Jeeze. It was change for a parking meter.” I feel my temperature rise. “I’ll repay you! And you can forget Julián because Julián and I are not together!” Papa’s eyes got cloudy as he aged, but not Mama’s. Her eyes are like new-minted dimes, bright with gotcha. “I don’t forget. Julián shouldn’t be borrowing from old ladies. I’m glad you’re rid of him. It’s better to be alone, Raquel. You’re smart, like me. The smartest of my children.” I’m floored. Mama has never expressed the slightest interest in my life or anyone else’s for that matter. Although mortified by the comparison, I can’t help being flattered that she considers me the smartest. “So,” I say, softening. “You’re renting a piano?” Her arms fold defensively. “It was on sale.” “You bought a piano?” Baffled, I pull out a chair and sit at the kitchen table. “For my music lessons, Raquel.” Still standing, she bristles with nervous energy, her pendant flipped so that it reads “eittoH”. “What about the keyboard Tito got you?” “I need a real piano. Besides, Tito steals from me.” Yup. Genial to eccentric to crazy at maximum velocity. The woman who brought me into this world is fundamentally incapable of being the mother I long for. I know this in my heart, in my brain, in my gut, in my very pores, and yet she gets me every time. I rise to tighten the dripping faucet, then turn to face her. “Look, Tito’s here every weekend, and when he can’t, he calls to see how you’re doing,” I say, defending my brother. “Why do you give him such a hard time?” A better question is why am I trying to reason with her? “You know damned well I can’t trust him.” I take slow, deep yoga breaths. Do not engage. Do not engage. Mantra for Mama. Outside, a vehicle rumbles to a stop. “It’s here!” she says. I follow as she rushes down to the sidewalk, patting her hair in the mirror on her way out. A deliveryman in a maroon jumpsuit strolls toward us from a double-parked delivery truck. “Piano?” he asks me. He has sleepy eyes, a pencil-thin mustache, a clipboard. “You’re late!” Mama says. “Sorry, ma’am.” He tips his cap back. “I’m Jesse and that’s Murphy.” Murphy is pulling a ramp from the back of the vehicle. Mama ignores Jesse’s proffered hand. “Where does it go?” he asks me. I blink, smiling. “I’m just an innocent bystander.” “Up here,” Mama interjects, leading us up the steps and into the living room. “You ordered a Yamaha grand?” Jesse is finally addressing questions to the right person. “Ma'am, we get a nine-footer in here and you won’t have room to sit down and play.” “There must be a mistake,” I say. “I don’t need much room,” Mama says, shooting me a dark look. “Move, Raquel, you’re in the way.” So be it, I think. I’ve always been in your way, we all have, Papa, Ellie, Tito. You could have continued therapy, taken the pills, and avoided the crises that your family—not that you recognize us as family—have had to rescue you from over the years. Selfish, selfish, selfish. I back myself against the hallway wall as the movers expertly rotate the piano to make the tight turns. Well, I’ve done my duty. My report to Ellie: Mama is alive. Mama is well. Mama is impossible. “I’m coming back this weekend for Papa’s stuff,” I say, “and will you please answer your telephone? Because Ellie and Tito worry about you.” As I take off, I hear Mama telling the deliverymen, “There’s ten dollars for you when you’re done.” **** On Sunday Tito is wearing his annoying “I’m just a regular vato from the barrio” get-up—Ben Davis work pants and his “Stay Brown” t-shirt from the San Jose Flea Market. We’re both wearing Giants caps. The sun is out, there’s a game this afternoon. I’m anxious to get back to the Galería where volunteers are painting the walls. “We’re here for Papa’s things,” I say, when Mama comes to the door. She is channeling Cher today: red tunic, shaggy vest, ankle boots. Gray wisps escape a blue-sequined beret the size of a small pizza. “God, open a window! Aren’t you hot?” “Leave me be, Raquel. You know I’m always freezing,” she says. “I'll make coffee now that you're here, Tito.” My brother is definitely her favorite child. There are times I believe he is the only person in the world who can get through to Mama, but when I really think about it, I shake my head, No. Because after his visits she accuses him of stealing and she cries. Always. “Momskh!” Tito says, draping his beefy arm around her shoulder, “Where’s the pianoskh?” Mama’s eyes light up. Tito has invented this Russian-esque language just for her. “Who told youskh?” she giggles, leading us to the living room. Tito halts theatrically in the doorway, throws his hands up in wide-eyed astonishment, “Whoa! That’s some piano!” The piano is impressive, gleaming ebony, padded leather bench tucked underneath, filling the room like one of those clipper ships crammed inside a tiny glass bottle. “What do you think?” Mama is giddy. “What do I think?” Tito bellows. “What do I think? Takes up a lot of space!” Somehow this is the right answer. Mama practically squeals with pleasure. If there were room she’d be pirouetting around the piano. “It's ridiculous,” I say, addressing Tito. “If she needs a so-called ‘real’ piano, which I doubt, a used upright makes more sense.” Tito’s look tells me to can it. “This is a piano for professionals,” I emphasize, unable to help myself. I’m the director of a community arts center. I believe that everyone has the capacity to make art, to enjoy a creative life. This is my work, yet I can’t manage to extend this value to Mama. I feel like a miserable imposter. “I love it,” Mama says, defiantly. “Play us something, Mom!” Tito doesn’t have to ask twice. Mama climbs onto the bench and sorts through dog-eared sheet music. She begins playing “De Colores” and Tito, leaning over her shoulder to read the lyrics, sings with her. Both are seriously off-key. I escape, taking the kitchen stairs down to the backyard where weeds are suffocating Papa’s tomato plants, and enter the garage from the side door. Underneath the floorboards, the caterwauling is mercifully muted. Papa sold his car awhile back, so the garage is now storage space. I wade through boxes and furniture before I find what I’m looking for: Papa’s brown leather suitcase. Wrenching it free, I wipe the cobwebs with an old t-shirt and sit cross-legged on a box, my heart at peace. The tarnished metal fasteners make a satisfying pop. Lifting the lid, the faintest scent of tobacco in the yellow silk lining sweeps me back to another time. It must have been fall. The living room windows were dripping condensation. Mama had been gone a year. I was still crying myself to sleep. Papa set the suitcase on the coffee table. “Let’s see what we have here,” he said, a cigarette in one hand, a can of beer nearby. His hair was still coal-black, but he was starting to get a paunch. He’d drag out the suitcase now and then, often during the holidays, to show us his treasures—a jumble of photographs and souvenirs—a pretext for his stories of back home. That day it was only me sitting by his side on the worn sofa. I reached for a sepia-tone studio portrait of an elegant native woman in a 1940s fur coat. “Who’s this?” I knew the story by heart, but I never tired of his stories of wicked uncles and chain-smoking grandmas, homesteads and adobes, farmers and dressmakers, sheepherders and coal miners, pueblos and penitentes, trains, abductions, adoptions, fires: tales of love, tragedy and survival reaching back across generations to New Mexico Territory and beyond. “My first cousin Josie, on my mother’s side. She had a tailoring shop in Santa Fe. She was a sharp cookie, married and widowed three times, the last husband a Navajo. She liked them young but it didn’t matter. They still died on her.” We chuckled. I pulled up an unfamiliar snapshot of a couple picnicking on a blanket at Ocean Beach, the Cliff House in the hazy distance. “And this one?” A shadow crossed Papa’s face. With a sinking heart I recognized my youthful parents in a happier time. Silence flooded the room. Papa’s thoughts seemed to alight on something not in the picture, the ashes on his cigarette trembled. Finally, he smiled, seemingly chagrined by his thoughts. I switched the photo for one of Papa as a boy and his older sister posing in front of a Ferris wheel. “I wished I’d known Auntie Rose,” I said. Papa never returned to New Mexico after he and Mama moved to San Francisco—his immediate relatives had moved away or died by then. If there were other reasons, he never shared them. “You remind me of Rose, mi’ja,” he said. “Sparky as hell.” Besides photos, there is a ledger of the early 1900s written in Spanish and English, discharge papers, faded postcards from distant relations we children never knew, yellowed newspaper obits, a ruby ring won in a poker game, a ring neither ruby nor gold. This is what I came to rescue from Goodwill. My father’s life in a suitcase—all we have left of him besides his stories etched into our memories, tales that kept our family tethered to our history, to this land, to each other. I secure the suitcase, one snap at a time, and haul it up the back stairs to the living room where Tito and Mama are hammering out “That’s Amore.” Tito insists on getting burritos and a six-pack for lunch. We dine on the kitchen table of our childhood, while Tito tells us about his new lady friend, a teacher. Mama tracks his every word, the better to throw in his face one day. Tito is oblivious. Someone in the building has the game on, radio turned full blast. “The bases are loaded with two men out! Herrrrrre’s the pitch!” When we were kids, listening to the Giants with Papa was the best. Halting in the midst of whatever we were doing—peeling potatoes or washing the car—to visualize the players at the ballpark, we held our breaths, waiting to hear Jon Miller yell, “The ball is up, up…it’s out of here!” My spirits lift remembering how we’d yell and high five each other. Then the heaviness in my chest returns. I claim the suitcase when it’s time to go. The rest of Papa’s things will go into Tito’s garage until Ellie can come out to help sort it all. On the sidewalk, Tito stretches and grins. “Mom’s doing okay,” he says. “We’ll just have to check in on her more often.” “Do you know what a piano like that costs?” Tito’s smile vanishes. “Don’t worry about it, Rocky, I got it covered.” “She can’t wait to get rid of his stuff.” “You can’t know how anybody feels except for your own damn self.” Tito’s voice is hard. “Mom does the best she can. You’re past forty. Is this who you want to be? We grew up with her too. And what’s with that haircut?” Glaring at my brother, I slam the trunk lid closed and get into my car. Wiping away tears, I turn onto Valencia Street, glad to be heading to the Galería. Three signal lights later, I realize I’ve forgotten my Giants cap and make a U-turn in the middle of the street. On Bartlett I drive by two little girls playing hopscotch on the chalked sidewalk like Ellie and I used to do, and pull up in front of the Lermas’ building that has a For Sale sign. Sal is sitting on the stoop, drinking beer and listening to oldies on KPOO. “Hey Rocky. Sorry about your father,” Sal says, as I exit the car. “We lost a good man.” “Thank you.” I’ve known the Lermas since forever and wonder whether they’ve found a place to move to. Before I can ask, I’m distracted by the faint sound of music coming from Mama’s flat. I climb her stairs and peer through the open bay window, past the lace curtains, where she sits half-hidden behind the big, lacquered instrument. Her fingers strike the keys as she squints through her enormous, red-framed glasses at the sheet music, her voice tentative. “Sweet dreams till sunbeams find you…” The playing is measured and precise. The voice not so much, even as it picks up tempo and exuberance. “Sweet dreams that leave all worries far behind you…” I take a breath as my heart unexpectedly catches on a surging memory of Mama sitting on my bed when I was a girl, singing me to sleep. Cozy in pajamas, bed covers pulled up to my chin, lulled by her voice, drowsy. Back when she was still my Mama. “And in your dreams, whatever they be…” Mama warbles with joyful enthusiasm. The afternoon’s heat has eased. Rising above the ambient sounds of the street—a plane overhead, a skateboarder rolling past—is my mother’s voice falling in and out of tune like a kid learning to ride a two-wheeler. Mama in her blue-sequined beret is swaying, creased fingers moving over the black and white keys of the piano, focused on the task, determined like all of us to catch beauty in this precarious life. The sound of the music awakens a raw tenderness in me, if only for the moment. Brushing unexpected tears from my eyes, I sink onto Mama’s front steps to listen.  Linda Zamora Lucero is writing a collection of short stories set in San Francisco’s multicultural Mission District where she was born and raised. She identifies as Chicana, and attended Mission High School, City College of San Francisco and SFSU. Her published short stories are: “ZigZag,” LatineLit Magazine, 2022; “Speak to Me of Love,” first prize winner, DeMarinis Short Story Contest, Cutthroat: A Journal of the Arts, 2021; “When It Rains,” Yellow Medicine Review, 2020 Pushcart nominee; “Mexican Hat,” Puro Chicanx Writers of the 21st Century 2020 Anthology; “Balmy Alley Forever,” Yellow Medicine Review, 2016; and “Take the Money and Run–1968,” Bilingual Review, 2015. Lucero's day job is directing the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival, an admission-free outdoor performing arts series in San Francisco.

0 Comments

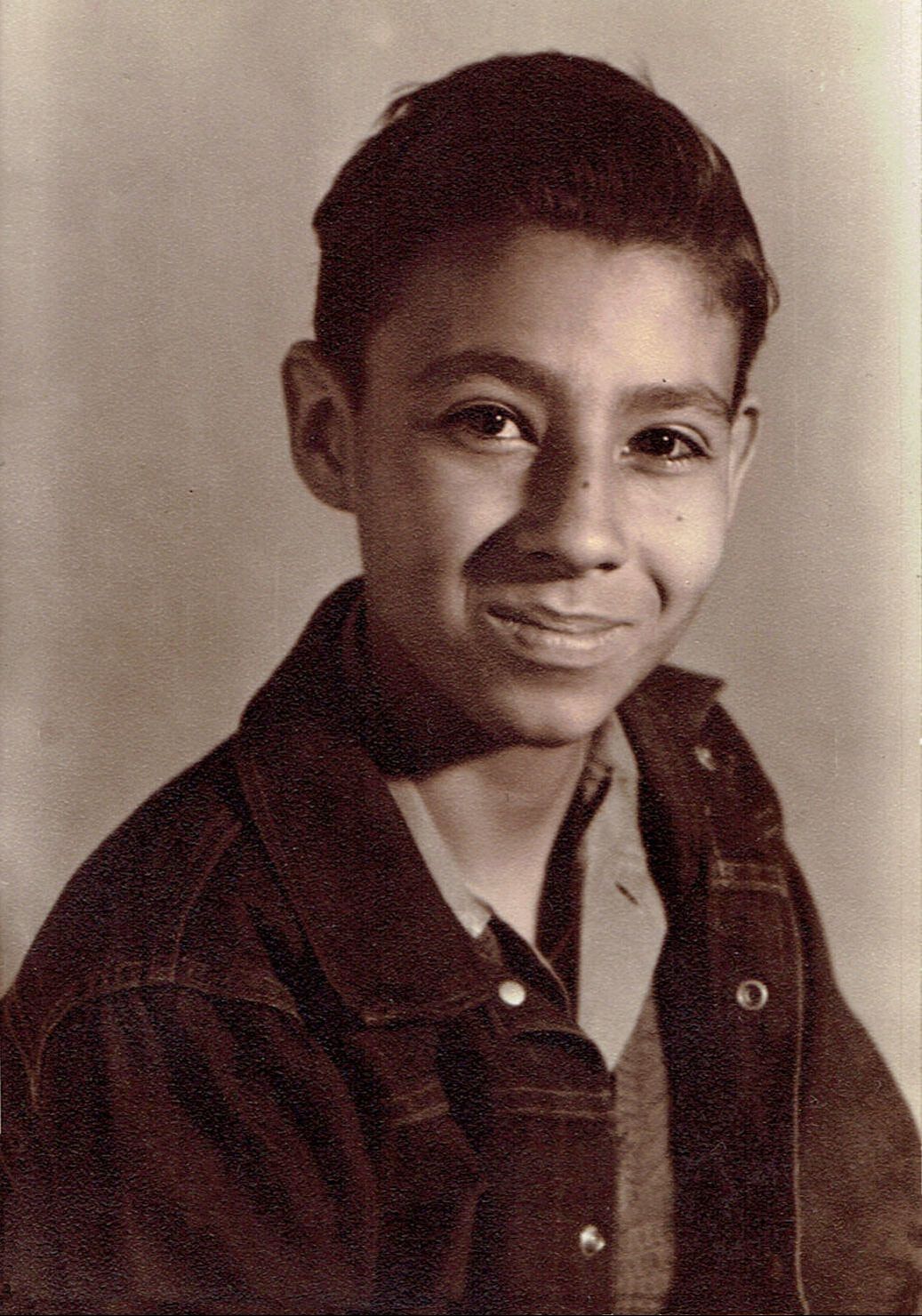

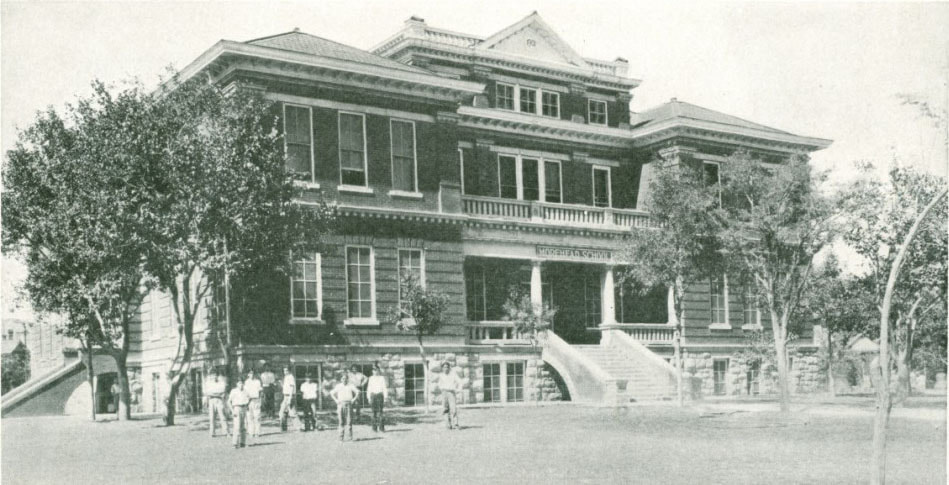

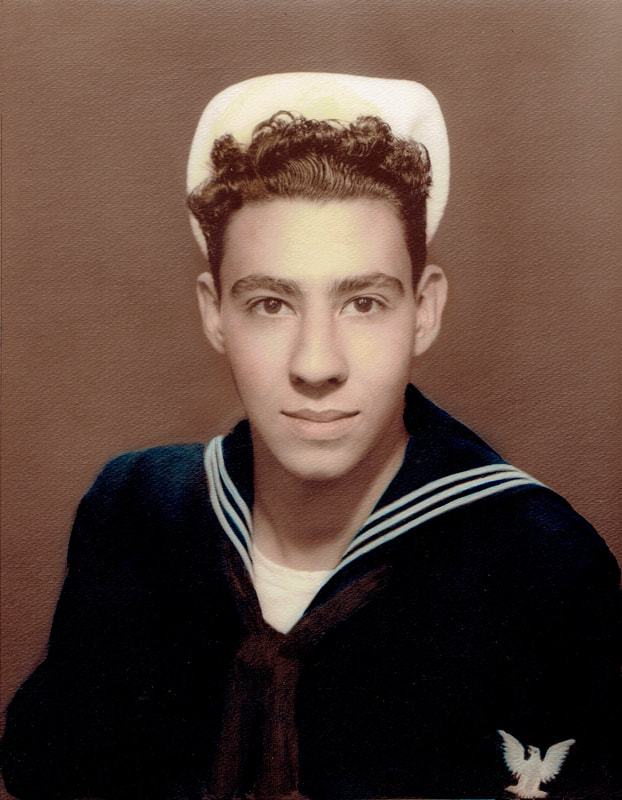

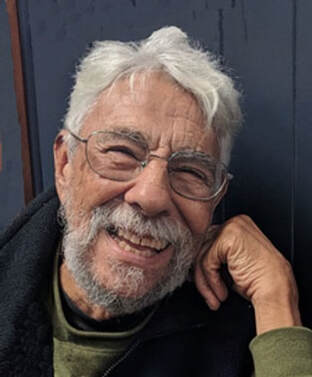

Mrs. Reed’s Christmas Treeby José Antonio López In addition to sharing our early Texas history with others through my Rio Grande Guardian online newspaper articles, I also wrote about growing up in El Barrio Azteca in Laredo, TX, such as the example below, first published on December 24, 2013. It describes the time when I first learned of the special Gift of Giving during the Christmas season, and whose message still applies today. Wishing you and yours a very Merry Christmas (Feliz Navidad) 2022. For most people, childhood Christmas memories serve as imaginary gold nuggets treasured for a lifetime. One of these gems is also my earliest recollection of when I first learned the true meaning of Christmas giving. It was 1953; I was about nine years old and in Third Grade at Central School in Laredo, Texas. Mrs. Reed was my teacher. Authoritative, yet warm and friendly, Mrs. Reed was a classic elementary school teacher. Effective and practical in her no-nonsense approach to teaching, she constantly challenged us to learn. In her classroom, “Eyes and ears on the teacher” was the rule. A few days before the Christmas holidays vacation, she would purchase a small Christmas tree and placed it in the middle of one of the classroom work tables. She also bought the tinsel and garland. Then, each student in class was asked to donate one ornament. They could either make it in class or bring one from home. Trimming the tree was an extra treat for us students. As a reward for good behavior, she allowed us to help her adorn the tree, which was done a little each day. By the time we had our class Christmas Party on the last day of school, the tree was finished. Not all teachers went the extra mile. So, after lunch on that special Friday, teachers formed a line outside our classroom and brought their students to view and admire our creation. Barrio El Azteca was mostly poor blue-collar. Most of our neighbors were hard-working day-labor folks and migrants. They arose before day-break and returned home at nightfall; dead tired after their day at a building site in town or working at one of the area’s ranches and farms. The next day, they did it all over again. Their pay was dismal; and employment for day laborers was erratic. Knowing that Christmas trees were a luxury in some children’s homes, Mrs. Reed responded with her own style of kindness. During the last day of school, she put all our names in a bag. She then asked a fellow teacher to pick a name from the bag. The student whose name was drawn won the Christmas tree. More than anything that particular Christmas, I prayed that I would be the lucky winner. Having overheard my parents a few days earlier, I knew money was tight in our monthly budget. It seemed that they might not be able to buy a Christmas tree for us that year. That’s not to say that our house wouldn’t be decorated for the season. Mother always did a great job decorating our home with very limited resources. Too, the center point inside the house was a small Nativity set in the living room. Yet, the spot reserved for the tree was empty. So, it was with great anticipation that I welcomed the last day of school before our Christmas break. The Christmas Party was well underway that afternoon, when all of a sudden, I heard my name called. I couldn’t believe it. I had won the prize. When the dismissal bell rang, I asked Bernardo, a classmate, to assist me in carrying it home. He agreed. Mrs. Reed helped us remove some of the breakable ornaments and she put them in a small box. As soon as we reached the outside of the school building, every step of the way became difficult. First, we had to maneuver a steep stairway in front of the school entry. In one arm, Bernardo carried our notebooks and in the other, the small box with the ornaments. I carried the tree still sporting the tinsel and garland. Second, balancing the tree upright in front of me, my view was very limited. Walking on the unpaved, gravel, street was tricky. So I walked on level ground, avoiding any large rocks that might make me fall. A slight wind was blowing and small bits of tinsel were dropping off the tree, marking our way. We were a sight to behold! Our house was about six blocks from Central School. Bernardo’s house was half-way to mine. So, before we knew it, we had already walked the three blocks to his home. I placed the tree on the ground and waited for him to drop off his school books and tell his mom he was helping me get home. After a moment, his mother walked out to admire the tree and went back inside. It was then that I realized Bernardo’s home didn’t have a Christmas tree. Suddenly, a hard-to-explain powerful feeling overcame me. I asked Bernardo to open his front door. Before he had a chance to ask why, I carried the tree inside and placed it by the front window. Hearing the commotion, his mother walked out of the kitchen and I asked her if she would like to keep the tree. She was stunned, and began to weep. She gave me a big hug, nodded “yes”, and thanked me. Then, I helped Bernardo put the ornaments back on the tree. It immediately brightened up the room. As I left, the two of them were quietly standing admiring their beautiful Christmas tree. When I got home, other kids had told my mother of my winning Mrs. Reed’s Christmas tree. As soon as I entered our home, Mother asked me where it was. When I told her what had happened on my way home, she began to cry just like Bernardo’s mom. Mother gave me my second big hug of the day. She then called Dad at work and told him what I had done. My father, a stern man of few words, but possessing a big heart himself, approved of my charity. That evening, he returned from work with a Christmas tree strapped to the top of his car. In summary, I tell this story to focus on the plight of today’s needy. Having lived the experience, I am in a position to say that poor people don’t enjoy being poor. Nor are they lazy. That is why they don’t deserve the unkind treatment they receive almost daily from politicians and some news commentators. The fact is the poor are in a never-ending struggle to improve their quality of life. They only ask for a compassionate helping hand to grab onto the next rung in the ladder of success. This Christmas let’s all be part of the solution by helping them do it.  José “Joe” Antonio López was born and raised in Laredo, Texas, and is a US Air Force veteran. He now lives in Universal City, Texas. Joe is the author of several books. His latest is Preserving Early Texas History (Essays of an Eighth-Generation South Texan), Volume 2. Lopez is also the founder of the Tejano Learning Center, LLC, and www.tejanosunidos.org, a website dedicated to Spanish Mexican people and events in U.S. history that are mostly overlooked in mainstream history books. A una anciana Venga, madre— su rebozo arrastra telaraña negra y sus enaguas le enredan los tobillos; apoya el peso de sus años en trémulo bastón y sus manos temblorosas empujan sobre el mostrador centavos sudados. ¿Aún todavía ve, viejecita, la jara de su aguja arrastrando colores? Las flores que borda con hilazas de a tres-por-diez no se marchitan tan pronto como las hojas del tiempo. ¿Qué cosas recuerda? Su boca parece constantemente saborear los restos de años rellenos de miel. ¿Dónde están los hijos que parió? ¿Hablan ahora solamente inglés y dicen que son hispanos? Sé que un día no vendrá a pedirme que le que escoja los matices que ya no puede ver. Sé que esperaré en vano su bendición desdentada. Miraré hacia la calle polvorienta refrescada por alas de paloma hasta que un chiquillo mugroso me jale de la manga y me pregunte: — Señor, jau mach is dis? -- To an Old Woman Come, mother— your rebozo trails a black web and your hem catches on your heels, you lean the burden of your years on shaky cane, and palsied hand pushes sweat-grimed pennies on the counter. Can you still see, old woman, the darting color-trailed needle of your trade? The flowers you embroider with three-for-a-dime threads cannot fade as quickly as the leaves of time. What things do you remember? Your mouth seems to be forever tasting the residue of nectar hearted years. Where are the sons you bore? Do they speak only English now and say they’re Spanish? One day I know you will not come and ask for me to pick the colors you can no longer see. I know I’ll wait in vain for your toothless benediction. I’ll look into the dusty street made cool by pigeons’ wings until a dirty kid will nudge me and say: “Señor, how mach ees thees?” — RAFAEL JESÚS GONZÁLEZ © 2022 BY RAFAEL JESÚS GONZÁLEZ Riffs sobre el poema |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed