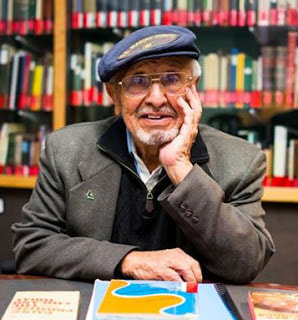

A Eulogy to By Armando Rendón A life-long friend and colleague, Felipe de Ortego y Gasca, has passed away today; he is now one with the universe as he was one with so many of us in life. Felipe invented Chicano literature because, as I see it, his studies into the early writings by Chicanas and Chicanos provided not only a scholarly basis for the field as a genre of American literature but inspired many of our indigenous-hispanic writers to put pencil or pen to paper, pick out letters for a manuscript on the old manual typewriters, and today tap out a poem or novel on a laptop while commuting back and forth from a job. We go way back to 1972, when an ambitious young man (I think we were all something like that then) named Dan Lopez got the idea for a print magazine he called, Nuestro. The project was ahead of its time and folded in a few years, but Felipe and I were recruited by Dan to help make the magazine go, Felipe as editor and I as a freelance writer and photographer. We struck up a friendship and kept in touch over the years. I learned much later that Felipe had dropped out of high school in 1943, yet wisely took advantage of the G.I. bill to get a BA at the University of Pittsburgh in 1948, then a Master’s degree in literature at Texas Western College in El Paso, followed by his Ph.D. in literature at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque in 1971. He eventually earned a post-doctoral degree in Management and Planning for Higher Education at the Columbia University Graduate School of Business’ Harriman Institute in 1973. It was when I launched Somos en escrito Magazine in late 2009 that we hooked up again. So much of what Felipe wrote about Chicanismo from the literary aspect had not been broadly circulated that he found Somos a perfect vehicle to inform a new generation, and I gladly partnered with him in publishing as much as I could of his stories and literary critiques. I intend to work with his wife of many years, Gilda Baeza-Ortego, a scholar in her own right, to reveal other works he might not have yet offered to us. Felipe’s early service as a U.S. Marine during World War II—a feature on his tour of duty that took him to China accompanies this eulogy to him—served him well in recent years when he battled a variety of illnesses, such as the shoulder replacement he underwent earlier this year. I had invited him last spring to join me and a couple other Chicanan writers for a panel on Chicano literature to be presented in Cuernavaca in early August. I knew he was not at his healthiest but how could I not first ask the father of Chicano literature to address a conclave of international scholars on his favorite topic? He had accepted my invitation in a flash, but as it turned out, Felipe’s health failed him and he had to cancel the day before his and Gilda’s flight to Mexico. For sure, only a very severe ailment could have forced him to bow out. The other two panelists, good friends of his as well, Rosa Martha Villarreal and Roberto Haro, and I stepped up to present his “Cuernavaca paper” on his behalf. (Click on the link to read de Ortego y Gasca's Cuernavaca paper: FelipeCuernavacaPaper) Felipe de Ortego y Gasca lived a long and eventful life, leaving among many other contributions to Chicanismo and society in general, a legacy as a visionary scholar. Who would have guessed that today we would have the breadth of writing by Chicana and Chicano authors, in every genre and on every topic. He invented the Chicano Renaissance so he himself deserves to be called a Renaissance Chicano. May you rest in peace, old friend. Armando Rendón is founder/editor of Somos en escrito Magazine. A Chicano Christmas in ChinaBy Felipe de Ortego y Gasca This is a story about a Christmas in China after World War II and how the world changed for me as a consequence of that Christmas. Hard to believe that almost six decades have passed since VJ Day (Victory in Japan, August 14, 1945) and the end of hostilities for World War Two. By Christmas of 1945 the war had been over more than four months, just after President Truman had authorized dropping an atom bomb on Hiroshima on August 6 and one on Nagasaki on August 8. I felt ancient at war’s end. War has a way of maturing youngsters, growing them up quickly. There is also a mantle of invincibility that cloaks the young, woven of equal parts of arrogance and ignorance, strands of curiosity, and large patches of naiveté. It’s a wonderful time of life: full of joy one thinks will last forever; full of agony that seems interminable. I was a Sergeant of Marines then, filled with the exuberance of victory marking the end of a life and death struggle between the forces of good and evil, a struggle that claimed 50 million lives worldwide. I was 19 years old that August and the fates had kept me from harm thus far. Just two years earlier, on my 17th birthday, I had enlisted in the Marines, during the dark, grim days of the war when victory appeared implausible and the fate of democracy hung in the balance. The San Antonio of 1941, where a branch of my mother’s family settled in 1731, was a place of “brown blood and white laughter” as I wrote in a poem years later, remembering the city’s segregated schools and its English-only rules. Though the war transformed the city economically, a different kind of war would vanquish the barriers that had made San Antonio a divided community and strangers of Tejanos in their own land. At war, Tejanos showed their mettle, Boys became men. The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) suspended its annual conferences for the duration. On the home front, Mexicana Americans built planes, subs, and gliders; handed out donuts and coffee to America’s youth training at Fort Sam Houston, Kelly, and Lackland Air Force bases in San Antonio. Many became air raid wardens. On the West Side, Tejana mothers placed gold stars in their windows. On the day of infamy, I wondered if I could pass for 17, hoping the war would wait for me. I tried to enlist in the Army in 1942 but was turned away because I was too young at 15 for military service they told me even though the country was desperate for troops. I got as far as the physical before I was found out and turned away with an admonishment veiling a smile and an encouragement to try again next year. Did I know, they asked, that I had flat feet? By next year, I thought, there would be no glory left. But I waited, toughing out the 9th grade of school. I should have been a Junior but instead I was a high school Freshman, two years older than my classmates because I had repeated the 1st grade and had been held back in the 4th. I started public school as a speaker of Spanish in segregated schools and didn’t improve until I made it to the 5th grade. In January of 1943 I tried enlisting in the Navy but was rejected because of “color blindness,” not because of my age. When I turned 17 that year, I tried the Marines, color blindness, flat feet and all. They accepted me, and after boot-camp at Parris Island, South Carolina, I was assigned to the Marine Air Station at Cherry Point, North Carolina, from where I was sent to the 8th and I (Eye) Marine barracks in Washington, DC. From there I was ordered to the Marine barracks at Air Station Quantico, Virginia, from where I shipped out to the Pacific. After a stop at San Diego and Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands, I was part of the tail-end of the last campaigns in the Pacific. When Japan surrendered, American GI’s in the Pacific were grouped into those who had earned sufficient points for immediate return to the states and a victor’s welcome, and those who didn’t. Wartime service was after all for the “duration” and the war was not officially over until December of 1946 even though the fighting had ended more than a year earlier. Troops not returned to the states were massed into a force of military occupation for Japan and those headed for mainland China as an army of liberation to disarm the Japanese troops in China and to oversee their evacuation. China had been occupied by the Japanese since the 30's and at the outbreak of hostilities had interned the 4th Marines who had been stationed in Shanghai. China would be freed at last. The hop from Okinawa to Shanghai was short. On that rain-washed day I did not know my journey to China would mark the beginning of my search for America. An early day harbinger of Battlestar Galactica, the rag-tag fleet of American ships trailing up the Yangtze River toward Shanghai was heralded with cheers of jubilation and gratitude by the Chinese. “Ding hao!” they shouted. “Ding hao! Good, good!” But that mood quickly soured when the hive of sampans crowded the spaces between the ships and the smiling Chinese held out their hands for some token of largesse signaling our arrival. What turned the scene ugly was when the Captain of the U.S.S. Monrovia ordered the fire hoses turned on the Chinese clambering up the sides of the ship trying to get on deck. The Chinese were eager to greet us, but that greeting was met with disdain by those Americans who saw the Chinese as nothing more than “gooks” and could not differentiate them from the Japanese. The force of the water hoses sent the Chinese back into the mass of sampans, some of them falling into the water through the spaces between the flat dugouts. The scene became a melee when the sailors decided malevolently to aim their hoses at the people on the sampans. The Chinese were bewildered. Why would a liberating force treat them that way? Chinese women screamed as their babies were flushed out of their hands by the force of the water from the fire hoses. What should have been a celebration became a melee of confusion and grief. That was not our finest moment. Those images have remained with me ever since. Little wonder we lost China to Mao Tsetung in 1948, forced to take our troops to Korea. I was gone by then. I left China in 1946. But the specter of that moment did not deter me from savoring the experience of being in China, the land of Cathay, of Marco Polo and Genghis Khan. The Yellow Sea washing against a land already ancient when the sailors of Colón flitted from fleck to fleck looking for Cipango (Japan) was not yellow but emerald green in the time of my youth when all my dreams were green. Years later I would realize what a profound effect that experience in China had on me. My stay in Shanghai was brief. My outfit moved on. I was assigned to temporary duty with the 6th Marines in Peking and Tientsin. I was posted to duty with Marine Air Group (MAG) 24, First Marine Air Wing at Tsingtao, a key airfield in the Japanese occupation of the Shantung Peninsula just across from Korea. Tsingtao is a port city and at war’s end was once more bustling with the hum of international trade. In Tsingtao (which sounded like Chingdoh) I was looked upon with puzzlement. Was I an American Chinese? A Migua Chinee? They had never seen a Mexican American before. Yes, I nodded, good-naturedly. “Ding hao, ding hao!” Good, good! the Chinese responded with smiles of approbation. Was I the first Chicano in China? No. Twenty-five years later in El Paso I would meet a Chicano, Cleofas Callero, who had been a China Marine in the years between the World Wars. There were probably others before him. Some 30 years later, Carlos Guerra, the journalist from San Antonio would travel to China. So would Patricia Roybal of El Paso and her husband Chuck Sutton, heir of the publisher of The Amsterdam News. And in the 80's Rudy Anaya, the Chicano novelist, from Albuquerque, New Mexico, would venture to China and record his impressions in a work entitled A Chicano in China. My affection for the Chinese was regarded with mischief as word spread that the Sarge was a Chink-lover. Fortunately, hierarchy and rank are powerful investitures in the military, especially the Marines. The troops may have disliked my affection for the Chinese but they took orders from me, like them or not. Every day I dressed down some troop for dissing the Chinese. They were not our beasts of burden, though we employed them on the air base as if they were. In China, American forces rode roughshod over the Chinese, acting more like Alexander’s Macedonian soldiers than emissaries of freedom. The Chinese quickly saw me as a friend. I was invited into their homes. I became good at ping-pong. I went everywhere with confidence. American troops in China, as almost everywhere else, did not carry currency. Instead we were issued scrip—paper money backed by the U.S. Armed Forces. Chinese money was out of the question. With inflation, Chinese money was almost useless. GI’s collected it as souvenirs or for prospective wallpaper. The brothel of “white” Russian women in Tsingtao preferred goods for their services. Cigarettes were most preferable. Chinese merchants accepted scrip which they exchanged for currency. In Peking, Chiang Kai-shek was struggling to stabilize the monetary woes of the country. One evening, not long after I arrived at Tsingtao, the base responded to a fire alarm in the city. The British Officer’s Club had caught fire and needed help in putting out the blaze. The fear was that the fire would spread into the city and become harder to control. From the airbase, three runway fire trucks with foam screamed into the night roaring toward the glow of the fire in the distance. As NCO of the day, I was responsible for dispatching the fire trucks. The old China Marines used to tell stories about Chinese fire drills which I didn’t understand until the night of that fire in Tsingtao. What confronted us was both risible and tragic. Attempting to put water on the fire were Chinese firemen struggling with old-fashioned wheeled water pumps. One man pumped while the other directed the hose barely trickling onto the fire. The Chinese firemen smiled politely as they greeted us. We ushered them out of the way, and quickly funneled a sheet of foam over the fire. We had arrived just in time. Though the Chinese firemen could not have contained the fire, their efforts had given us sufficient time to get there and to put the blaze out. I recognized that the caricature of Chinese ineptness was compounded by their lack of available technology. Mao Tsetung recognized that lack also which is why he launched the Chinese Revolution. China had to enter the modern age despite its legacy as a victim of colonialism. The week before Christmas some of the men in my troop wondered if we could find a Christmas tree in the hills beyond the air base. “Whadaya think, Sarge?” “Sure, why not?” We weren’t prohibited from going into the hills, though we were counseled to be careful. The Chinese Communists had been massing in the North and there were reports that some of their units were heading south. I checked out a truck from the motor pool and with a patrol of men headed toward the rise of hills some four or five miles west of the base. Once there, we headed off-road toward a clump of Chinese pine trees and settled on a good-sized tree that we chopped down quickly and loaded onto the truck. As we were ready to mount up and head back to the base, one of the men called out, “Sarge, take a look!” Coming out through the trees were a number of platoons armed with carbines and wearing drab uniforms with no insignia. The one who seemed to be the leader came up to the truck, surveyed it, walked around towards the front where I was standing, all the while with his finger on the trigger of what looked like a rapid-fire carbine. His men stayed at a distance but with fingers at the ready on the triggers of their weapons. We had brought axes not weapons. I was the only one with a sidearm. I beseeched my men to stay calm. I could see they were nervous. But they were seasoned men. I mustered a subtle smile as the leader of the hostiles acknowledged me and proceeded to inspect the cab of the truck. On the passenger side of the cab lay the book in Spanish I had been reading off and on for some time: La Vida Trágica, The Tragic Sense of Life, by the Spanish philosopher, Miguel de Unamuno. Picking up the book, the leader of the armed men who by that time we had all surmised were Chinese communists, asked: “Y este libro, de quién es? Whose book is this?” I was startled by the expression, little expecting a Chinese to speak Spanish, at that moment and in that place. “Mine,” I said. “Es el mío.” “Hm,” he murmured, pursing his lips, studying me intently for a moment. He put the book back on the seat of the cab and mustering an equally subtle smile motioned his men back into the anonymity of the woods. Before disappearing into the trees, the leader turned and with a most subtle smile, waved. I waved back wanly, relieved that the incident turned out as it had. “What was that all about, Sarge?” one of the men asked. “I don’t know,” I said. “I don’t know.” Years later I would know, years after I had acquired a structure of knowledge into which to fit that experience. One day, epiphanously, I understood the significance of that moment in North China and the Christmas tree incident of that December. By then the homecoming parades had all been held and the heroes all properly heralded. The United States was almost back to normal. Uniforms with plastrons of medals had been hung in closets for a day when they would no longer fit. I was ready to begin my search for America. The roots of that search lay in China where I saw “the others” and saw myself in them. Though I had grown up in a segregated society I had never thought of myself as “the other.” But the war changed me and the way I was to see myself in the context of the United States. I learned that no matter that Mexican Americans had won more Medals of Honor than any other ethnic group in America’s defense, we would have to fight far fiercer battles to secure for ourselves and our children the fruits of American democracy. Though I had completed only one year of high school, nevertheless on the GI Bill I went to college after the war at the University of Pittsburgh where in text after text I studied I did not find myself nor my people. I did not find my people in the texts I studied at the University of Texas either where I pursued the Master’s degree in English. They were also not in the texts I studied at the University of New Mexico where I completed the Ph.D. in English renaissance studies, American literature, and Behavioral Linguistics. And because I could not find Mexican Americans in those texts, my life’s work became a crusade for their inclusion. In 1947 the city of Three Rivers, Texas, shamelessly refused to bury in its municipal cemetery a Mexican American GI whose body had been exhumed in the Philippines and brought home for a hero’s burial. Adamantly the white city power brokers would not yield from their decision. At that point Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson approached President Truman on the matter and he directed that Felix Longoria be buried in Arlington Cemetery among the valiant of the nation. Out of that incident emerged the American GI Forum, a separate organization for Mexican American veterans, an organization I joined. Since then, numerous like incidents have necessitated creation of many separate Mexican American organizations. It didn’t need to be that way. Once, we were all brothers-in-arms. In my search for America, I have often thought of that young Chinese communist who bade me good luck in a language my country sought to strip me of. I have thought often of that China of so long ago. Once, I harbored thoughts of returning to China to look for that young man who had perhaps read Unamuno’s Tragic Sense of Life−in Spanish and who at that moment may have seen me not as a Migua Chinese but as a literary kinsman. Who was he? And how had he come to learn Spanish? Was he perhaps a child of a Chinese Communist who had participated in the Spanish Civil War of the mid ‘30’s and was now a Maoist? Hm? The question has remained pervasive for me during all these years. Thinking back—over the years—the gains have been worth the struggle. Mexican Americans did their part in World War II. And in subsequent conflicts as well as prior wars. This is our country, too, for we are in the land of our ancestors when this part of the United States was Mexico; and when it has called, we have served. But I’m still looking for America, in the nooks and crannies of those years since VJ Day, the end of World War II, and that Christmas in China.  Photo by Alicia deJong-Davis Photo by Alicia deJong-Davis Felipe de Ortego y Gasca was Scholar in Residence (Cultural Studies, Critical Theory, and Social Policy) and Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Philology and Cultural Studies at Texas State University System-Sul Ross. This memoir, which first appeared in the Alpine Avalanche, August 3, 1995, was presented at the Multi-Ethnic Christmas Celebration hosted by the Jernigan Library, Texas AandM University-Kingsville, December 6, 2004, and includes material from the author’s piece in 1941: Texas goes to War, University of North Texas Press, 1991. Copyright ©2001 by the author. All rights reserved. *Photograph by U.S. Marine Corps, http://www.qingdaonese.com/us-marines-in-qingdao-1945-48/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32891790

1 Comment

Gerald Ortego

6/15/2020 08:51:48 am

He was a father to me

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed