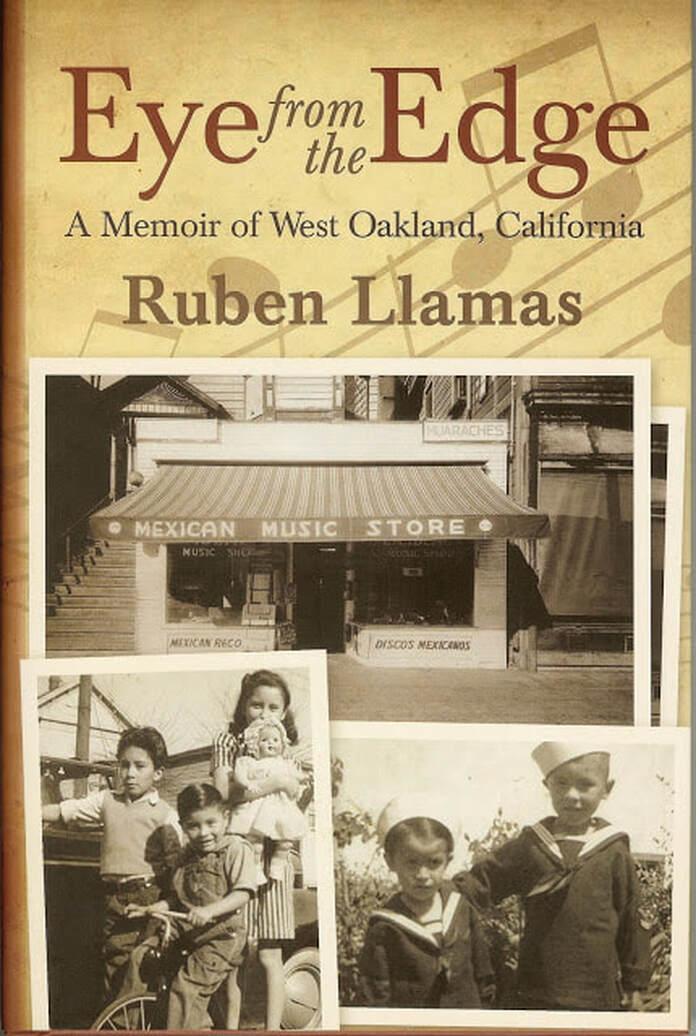

Excerpt from Eye from the Edge, A Memoir of West Oakland, California by Ruben Llamas First published on December 24, 2013, in Somos en escrito Magazine …Danny and I both stayed at St. Mary’s School for the rest of our grade school education. Education at the Catholic school was reading, math, and a lot of religion. They had a lot of rules, and boy, they enforced them 100 percent! Our parents supported these rules because they wanted us kids to get the discipline and education that we needed for our futures. The Holy Name Sisters taught at the grammar school that was associated with St. Mary’s Church. The Social Service sisters in gray habits taught catechism. Father Philipps was the pastor beginning in 1936 at this parish. We were active in most events of the school. The classes were small and the Holy Name nuns ran a tight ship. All the basics were taught. I can remember that penmanship was big. We spent a lot of time on cursive writing. English language was important. We didn't do any schoolwork with the Spanish language. The grade school was in a separate building on the lower floor. Above it was the school auditorium. We were active in school plays during the different seasons. All the classes had to participate. It was fun. I can remember starting class by reciting the Pledge of Allegiance to the American flag and then morning prayer. One of our teachers at St. Mary’s was Sister Mary Frances, a stern taskmaster with old-school ways. She taught the essential subjects and praying in class. She would have us hold our hands together with palms facing and our fingers extended. We had to make sure our palms were touching with thumbs crossed over one another in the form of a cross. If you were not complying with her instructions, she would pull your hair or whack you with her twelve-inch wooden ruler, hitting your hand and making it sting! Boy, you had to be alert in school or you got the ruler, no excuses. I remember the spelling bees and how the entire class, thirty or forty kids, stood around the perimeter of the room. One at a time we would be commanded to spell hard words. She would not let you sit down until you learned to spell the word correctly. I believe I learned a lot in her classes. Either she was tough or I got tired of holding my hands out and getting the twelve-inch ruler whack. The priests of the parish would often visit our classrooms. I can remember how she taught us to acknowledge the presence of Father Philipps or Father Duggan when they arrived. Sometimes we expected the priest and other times the priest would just surprise us, knocking and walking in. When he entered we stood in unison immediately and with a loud and enthusiastic voice greeted whoever it was, saying, "Good morning, Father." Sister Mary Frances did provide a quality education to us that helped us to succeed. Being boys, we would spend time talking about Sister. The big thing was the part of her habit she wore on her head. The habit was so tight-fitting on her head we thought she was bald or had a crew cut. We never found out. I remember she prayed a lot. During Lent she was into praying at the Stations of the Cross. Our principal, Sister Mary Guadalupe, was also into using her twelve-inch ruler. She had a large wooden crucifix with metal trim hanging from her neck. She was barely five feet tall but very intimidating in her body motions. She would use either of her weapons if you misbehaved. I remember Father Philipps pulled me up once by my sideburns when I was in the schoolyard doing something stupid. The memories of how they got our attention when we were being lazy and acting up worked. I graduated grade school, and I thank the teachers for my education that made me this person I am. The church was on the same block as the school. We put a lot of time into religion and prayer. Mass was a big thing. I helped out during Mass as an altar boy. This was an experience. I remember one priest who really liked his wine. It was something to pour wine into the gold chalice then see him drink it and get a refill. The wine was a good Napa wine. I did like the taste myself. Another thing I liked was the Latin Masses. I was learning Latin and I liked the High Masses. The funerals were very spiritual events. I liked the large candles and the holders. When I die I want the same type of candles and holders. When you served as altar boy for a funeral you got a cash tip. The school and the church were across from a park. The houses going further west toward the Southern Pacific yard were older and mixed up with smaller homes. These houses must have been built about the 1880s-1890s to accommodate the large immigrant groups. In those days people came from all over. European Americans, Africans, Portuguese, Irish, Italian, Dutch, Mexican, Japanese, and Chinese immigrants all settled in Oakland. The population in 1860 was 1,543. In 1910 it had grown to 66,900, including many folks who moved from San Francisco, especially after the devastating earthquake of 1906. During the 1940s before World War II, there was a theater on Seventh Street West called the Lincoln. We used to go there or to the Rex on Saturdays, mainly because of the double features. It was a fun day. Many African Americans lived in this area where the porters for the Pullman Company owned many of the homes. In this area of Seventh Street, many African Americans owned restaurants, pool halls, liquor stores, storefront churches, and music clubs like Slim Jenkins’, which I remember. The street was busy with people shopping, cars traveling the street, and streetcars and trains running. The west end of Seventh Street had a lot of restaurants with good southern food and music nightclubs such as Esther’s Orbit Room. The place had many southern blues clubs, attracting the young shipyard workers, new people from the South, and locals to these hot clubs of the day. In the 1930s and 1940s Slim Jenkins featured at his club some of the biggest names in jazz and popular music. The club was well-known among locals as a fun place for a night out. Other nightclubs in West Oakland were Sweets Ballroom and the Oakland Auditorium. The old-timers’ businesses in West Oakland saw the impact of the new wartime workforce. The shipyard workers would spend their money in the neighborhood. Years later twelve city blocks of this once-booming area were demolished to make way for BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit), Interstate 880, and the Oakland Main Post Office. Around 1949 I did a lot of bike riding with all my friends in these neighborhoods. This whole area had a multicultural environment. Riding through the streets was never a problem with the people. The Black kids knew us or knew that we lived in the same neighborhood. We played a lot of hardball - baseball at DeFremery Park and Ernie Raimondi Park. The local kids would hang out at the parks to have a baseball game or just practice. The parks were clean, the grass green, and the juvenile hall was next to DeFremery Park. You could talk with kids who were in confinement there. The exercise yard was just on the border of the park and we knew some of the guys. This north part of Oakland was more residential than Seventh Street. It was a neighborhood with a mixture of people. African Americans who worked for the railroad came from all over. This was especially true for the men who worked as sleeping car porters, dining car waiters, and cooks, and others who had seniority and wanted to have their home closer to their work or where the tips from the passengers were better. When the war broke out and the shipyards needed more workers, you had also African Americans from the Cotton Belt, mainly Texas and Louisiana, as well as the Okies and Arkies, moving into the established section of this area. When an old Victorian house was converted to take in a lot of these people, it was a crowd. I can remember my friend Art’s family in one of these large homes. They lived on the first floor and other families lived on the second floor or basement. Art’s house, as well as other houses east of Market Street near Eighteenth Street, was close to Cathedral of St. Francis de Sales, which was demolished after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Art had about three brothers and three sisters. His older brother was about the same age as my older brother, Mario. All of us would head over to other kids’ homes on our bikes or just hang out in the neighborhood till we had to go home. I would, on Saturday for sure, shine shoes in the barbershop. Saturdays were busy for everybody. The neighborhood was busy. People were around. They came during these times to Seventh Street to shop the local merchants. Remember, the outlying areas weren’t built up with big centers for shopping yet. People from North Oakland, East Oakland, Piedmont, and other areas would come downtown or to Seventh Street. When the barbershop was slow I would go downtown to shine shoes. The sailors and the army guys were always good for a shine. I had a spot on Tenth and Broadway, in front of Crabby Joe’s Big Barn. It was a great spot to shine shoes and sell newspapers. The military people always wanted to have their shoes looking good. They were on leave and most of them came downtown from all the nearby bases and from Alameda. Most of these guys drank a lot and loved the ten-cents-a-dance club above Crabby Joe’s. This group was always a fun group. They spent their money. I enjoyed this corner. It was exciting to see all the action around you. The people all had something going. It was a busy time for everyone, women, men, and kids. As a kid I saw the con men, gamblers, crooks, prostitutes, gypsies, and other people, all looking for a score. You learned to mind your own business, not to know or talk about what you had seen. If they trusted you, they would tell you a story or two of their activities. During this time I also sold papers, namely the Oakland Tribune and Post Enquirer, across the street in front of the liquor and cigar store. From the papers that sold, you received about three cents a paper. To me this was money coming in, plus the shine box money. I was on top of the world. As time passed, Joe, the owner, would have me run errands for him. I had no problems doing that because he would feed me pizza and a cola once in a while. Joe was the pizza maker during the late shift. He had a special window at the front where people would watch him prepare the dough. If he had people looking into the bar, he would show off, flipping the pizza in the air, and just put on a great show. The inside of Crabby Joe’s was something to see. They had a long bar from one end of the wall to the other. The brick pizza oven was toward the front. Across from the bar were tables where you could eat or drink; then came the dance floor. The bandstand was in back and had more light on it than a carnival stand. The big thing was the floor by the entrance and along the bar. Sawdust was all over the floor. This was typical of what I would call a joint. Also Joe had a large back room with tables for private card games. This old building would rock on the weekends. The music was popular country style--Okies and Western music--music you would hear on the radios of the 1930s and 1940s. This was music of the southern culture traditions that were being heard in Oakland with the influx of the newcomers. There was always some fight or something going on. The bands playing at Crabby Joe’s were well-known and played all up and down San Pablo Avenue. They would draw big crowds. It was music to make all people dance and have fun. Joe was a neat dresser. When he was not working he always dressed up. His slacks were sharp and cut well. His shirts fit neatly, and he always wore a neat sharp dress jacket. His shoes were always cleaned, shined, and casual. Joe was what I called in those days a San Francisco Sicilian Italian, with tanned skin and black wavy hair. Joe was well-known in this Broadway area of Oakland since most of the rough and tough bars and businesses were down here. The third floor of the old building had a hotel. I would sometimes run through the third floor trying to sell the last edition of the Oakland Tribune. This was an experience where I learned a lot as I did this selling. At most of the rooms, people would just not answer. The ones who did answer bought a paper and got you out of their way so they could continue their business. I would sell papers till about 5 p.m. or when I knew that the people who read the paper daily had their paper. They would always have the right amount, for they would fold it and put it under their arms like it was worth a hundred-dollar bill. They would tell you about the paper not being in order the next time they came by. The job of the paper-boy was to assemble the paper in sequence and sharply folded. While I was in the area I would go over to Fosters’ Restaurant. I know this place was not like the other places. They made a lot of sandwiches. The cream puffs and pies were great. The food was displayed in small compartments. You selected what you wanted out of these compartments that had doors. It was all self-service. You paid a cashier, then sat down at the round Formica and chrome tables. I sold the later paper here. When I was gone from my corner I would put up a cigar box for customers to drop monies off for their papers. I never had trouble with people taking my money. About 5 to 5:30 p.m., Radio, the newspaper collection man, would come to collect the newspaper money with his REO truck, a green panel truck with two doors, a double door in back, and no seat belts. Radio was about five foot six, maybe a Mexican or Italian. He had small facial features, big eyes, a great sincere smile, and he enjoyed laughing. He would pick up all the corner boys starting at Ninth Street all the way to Grand Avenue North, going up Broadway, next coming south on Washington. He would count your unsold papers and pay you off. While driving, Radio was a talker. He loved baseball. Radio was a good man. Once he gave all the kids a ride in his green REO panel truck to see an Oaks ballgame in Emeryville. The Oaks were Oakland’s minor league baseball team. After we were dropped off I would go home, visit the shop to see what was going on, then go upstairs to see my mom and get something to eat. If the timing were right, I would get my bike and search out my friends in the neighborhood. I would, by this time of day, go to Jefferson Park to see if any kind of game was going on. Across the street from Jefferson Park, St. Mary’s Church and School made a strong presence. Under the grade school they had a basement where they put in pool tables and a boxing ring to keep us boys busy. Father Duggan did this, and he had other programs to keep the young boys busy and away from the neighborhood pachuco gangs that were around our section of West Oakland. If no one was around I would then ride to Danny’s house on Myrtle Street. In the evening the wind really blew the estuary smell throughout the neighborhood. I could hear the ship and train horns on my route to Danny’s house on Third Street. Once in a while I would go down by the railroad tracks and follow them to Myrtle Street since the track went right to the Southern Pacific yard at the Point. Sometimes the guys were outside their houses. If not I just left for home to get ready for school or do some homework. At home about the only thing to do was listen to the radio. We had no TVs at that time. Friday and Saturday were busy days in the barbershop and music store. I shined a lot of shoes on the busy days. I was growing in these times, and I learned a lot about shoes. Sometimes I would go downtown to watch the Black guys shine shoes. They had a storefront on Broadway and Tenth. The small shop had four guys working it, and four stands with a lot of blues music playing. They would let me watch them and learn how to prepare the shoe for a great shine. They had a special wash for the leather. They applied the smooth-smelling shoe wax with their fingers and snapped the cotton shine rag, all in a rhythm of applying it. With the music blaring, the talking going on, it all flowed with the movement of the shiner’s body. It was an art in itself and great to watch. I would take their style of shine back to the barbershop and do my customers while snapping that rag like the pros. To this day I still have my red shoeshine box and enjoy the smell of the shoe paste we used to make those shoes sparkle. Some Saturdays the men’s discussions shared and compared the history of their countries of origin, such as Mexico, Cuba, Chile, Guatemala, Honduras, EI Salvador, Colombia, and Nicaragua. The history and cultures of all these men were interesting. I enjoyed hearing of Mexico and the Aztecs. The men talked of how the Spanish influenced each of these countries. The Spaniards conquered the Aztecs of Mexico in the early sixteenth century. The Aztecs had a great empire in Mexico City with pyramids and palaces, zoos and libraries that were similar to Egypt’s. Montezuma, the ruler at the time, had a large army. Cortés had an army of only 350 men and brought with him new diseases that killed a lot of Indians. The Aztecs had never had these European diseases. The story of the Aztecs is part of the history of the Americas and has always been an interest to me, but I don’t remember learning about them in school. At St. Mary’s School we learned about the history of the United States of America and the Catholic religion. This was basic in these times. And that’s the way it was. The men all had a story of their country and how the Spaniards exploited their country. These men that came in to see and talk with my dad and their friends were locals. They worked at foundries, at the shipyard, and as dockworkers at the local terminals. I would just listen to them and see the excitement in their discussion. I began to understand the conflicts between the Latino and the gringo cultures. The men would drink Four Roses whiskey or beer, then leave for the night. They were always dressed up so I knew that home was not their destination. I am sure of this. Some of the Saturdays before working in my dad’s shop, I would play ball at Jefferson Square Park. Baseball was my favorite sport. I played any position they gave me. I always enjoyed the game. Some of the guys played daily, and they were good. Saturday morning during the summer we played in a city league. The police department organized these games for all the kids in West Oakland. They had an old paddy wagon. They would pick us up at Jefferson Square Park and take us out to the city park in Oakland. We played all the teams. Then at the end of the season you played the City Best. It was fun. We met a lot of kids from the other parts of Oakland, mostly ages twelve and thirteen. We never had any problems with the different multicultural groups. I believe we all understood that we came from different and tough neighborhoods so why get an attitude. We would just fight it out. Some of the boys were good players. They also liked a good fight and that did happen once in a while. If you came from West Oakland Seventh Street, they seemed to leave you alone. Our Seventh Street in West Oakland had a bad reputation during these times.  Ruben Llamas, born in Oakland, California, just before WWII broke out and changed all our lives, recalls what it was like to grow up in a bustling time in diverse neighborhoods which urban development wiped out. From shining shoes in front of his dad’s music store, he rose from being a shopping cart boy of a retail company to its vice president. He now lives in Carmichael, California, with his wife, Anita. Editor’s Note: I grew up in East Oakland on the other side from where Ruben grew up and remember well how different the 1940’s and 1950’s were from today; Ruben’s story strikes the ring of truth. Those were the days, my friend. His memoir is available through Earth Patch Press, www.earthpatchpress.com, or online booksellers.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed