|

You may download a pdf of all three parts below.

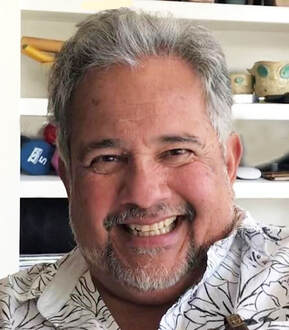

Small Startup Chicano Colleges: Models for Future Higher Education The lessons learned from Chicano college start-ups provide a strategy for using Enterprise Architecture and Systems Engineering as tools for restructuring higher education. PART II  Artist Daniel DeSiga, 1975. © Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto. Artist Daniel DeSiga, 1975. © Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto. César Chávez always seems to be nearby, guiding my thoughts. I have after all inculcated his values and beliefs into my own; I’m keenly aware of the impact his values have on the manner in which I construct my reality in everyday life. César’s values are exuded in everything I do, especially in special projects like starting brand new colleges and universities. Due to the COVID-19 virus I have been in lockdown in Salem, Oregon, just 18 miles from Mount Angel, Oregon, home of the former Colegio César Chávez as my son recently located here from inner-Portland. Because I want to save lives, I stay at home, think and rethink. There are endless reasons the lockdown has been problematic, for me, because I want to visit the physical plant of the former site of the Colegio César Chávez. I want to walk the halls, I want to touch the walls, I want to walk through the rooms where the Andrew Parodi Family lived at the Colegio in their capacity as groundskeepers. I have an affinity to this reality as my family served as the groundskeepers at Frances Parker School in San Diego where my sister and I were the only students of color and we spoke only Spanish. I want to feel César’s spirit as I know he left spiritual DNA behind on his visits to the college. I feel like conducting an in-service workshop about the STEM movement (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) to the Benedictine sisters who run St. Joseph’s Shelter in the building where the Colegio once operated. They are innovators in education in their own right as they have long believed that our institutions of education are failing us, so they may find my new book Theorizing César Chávez: New Ways of Knowing (2020) interesting. I am quite willing to conduct such a workshop as I feel the need to make amends with Benedictine sisters (Sister Julissa in particular) given my rocky relationship with them as a youngster. I’m reminded of how they are concerned about taking care of Mother Earth and that just like César Chávez they want to see her healthy once again. Similarly, in his latest book First Lady Pope, Pulitzer Prize winning author, Victor Villaseñor, was once invited to meet with retired sisters and priests to discuss his book and like me, he was hesitant for reasons related to corporal punishment, but he went anyway and was pleasantly surprised because he learned to forgive. Victor’s message is that “modern civilization has lost its connection to nature and the understanding of our natural, loving Feminine Energy which nurtures all life.” This is precisely how César Chávez felt and the precipitating factor why I founded the Big Sur Environmental Institute in writing a vision statement while infusing his values. I feel an existential pull to discover the realities behind Colegio César Chávez. It’s like the time I climbed the Temple of the Sun at Teotihuacán; when I made it to the top, I was rendered speechless knowing that I am related to this wonderful civilization. I thought, “What an honor.” I experienced a true sense of place, as I do amidst the concrete spikes in Chicano Park that are driven into the heart of our community. How else can I explain it? I feel both César and Diosito tugging at my coat tails, I can hear César now as he is speaking to me from above as he often does and his voice and message is clear, “Go take a look, Sonny Boy, go and see what you can learn, go talk to the founders and/or the graduates of the Colegio. You know how to start universities/colleges, Sonny Boy, you’ve been doing it your entire career; there is an opportunity to serve out there, started by the pandemic, there is opportunity to help educationally underserved people of Aztlan, go and check it out and get back to me, andale!” I am more than aware of the heroic efforts of founders of the Colegio César Chávez (1973 -1983) as they were an inspiration to me and my colleagues when we founded the InterAmerican College in National City (South San Diego), California, with a Chicano ideology and vision. I observed their efforts from afar, as I found the idea of a Chicano college quite fascinating, and it has remained as a grand value in my work. When I observed the numbers of Chicano graduates from the Colegio César Chávez, comparatively speaking, I became aware of the numbers of Chicano graduates throughout the American Southwest at state supported institutions of higher education like the University of New Mexico, New Mexico State University and the New Mexico Highlands University in Las Vegas, New Mexico. The insight at the time was that in 1978 the Colegio granted more degrees to Chicano students than the sum total by the University of Oregon and Oregon State University. Now just stop and think about that for a moment. Here is this small, relatively obscure institution in a rural German-American historic town outside of Salem, Oregon, and they were successful at garnering federal funds to build a campus and fund academic programs that led to full accreditation. Moreover, their statistics for graduating Chicanos/as were competitive with large state institutions; it didn’t make sense to be sure, but it did reveal the realities of this former Confederate State. I can’t tell you how disappointing it was to hear that in the early 1980s the Colegio César Chávez was becoming more-and-more heavily scrutinized by the regional accreditation body to the point that even though they earned accreditation, they were simply not financially sustainable. Just prior to closing, the Chicano icon José Ángel Gutiérrez was being considered as President of the Colegio, but the timing was off. Why is it that the Colegio came under such close scrutiny that they had to close their doors, compared to the scrutiny brought to bear, say, on the University of Oregon or Oregon State University or other any other state university for that matter? Let’s draw an analogy to the current state of play using the overnight adoption of online instruction in higher education. Within the impact of the current day pandemic universities/colleges across this nation (and world) transformed to online curricula literally overnight, yet their online curricula and faculty competencies were not evaluated nor assessed; they simply made the change. The reality is that non-traditional institutions like the University of Phoenix, Walden University, National University, InterAmerican College and the Colegio César Chávez were and are held to a much higher standard when adopting online teaching and learning than state-supported institutions and it shouldn’t be that way; it’s simply not right! There remains in American society a stigma. In referring to small start-ups and/or Chicano-oriented schools such as the Colegio César Chávez, American society still attaches the stigma of being a “university without walls.” When we earned full accreditation in the founding of the InterAmerican College (a Chicano college) much of the stigma of online learning had changed. The accreditation body was even inferring that we must incorporate online instruction, state our learning outcomes clearly, and demonstrate how we will reach them, so we hired the best leaders in online learning from the University of Phoenix. I can say with confidence that the University of Phoenix has the best leaders for designing online instruction. I have spent my career researching online teaching and learning and I founded a highly successful international online consortia called BESTNET with senior engineers from ARPANET, a precursor to the Internet (I nearly created the Internet!), so I have a great deal of experience in assessing education delivery systems. Yet today, in a time of a global pandemic, thousands of public/private universities are forced to adopt online education (mostly 100%) and are not being required to meet the same standards as small private institutions and/or non-traditional institutions of higher education. Moreover, just a few years ago a national campaign arose against “predatory colleges” that were seen as offering inferior online curricula and false promises like “Get in, get out, and get a job!” For instance, the 80 campuses of the Heald College system in California were defined as a “predatory college” and targeted due to a handful of complaints and subsequently forced to close its doors by the U.S. Department of Education. What I directly observed in the region where I live was that for Latinos in Monterey County and the great Salinas Valley and 79 other regions where Heald had campuses, Latinos lost out. Heald was located in regions with a lot of Latinos and many attended to earn vocational and/or occupational health professions degrees. Just look around and see who occupies many of the health professions positions, like medical/dental assistants, community clinic managers, hospital administrators, nurses and the like; the majority of people in these positions are Latino and trained at Heald College. To be sure, Heald’s tuition fees were higher than those at state colleges, but it’s only the case if you don’t figure in dorm life and food. Latino students at Heald were presented with student loan packages not any different than those presented to students at state colleges, so why then were they targeted as “predatory?” Couldn’t the same be said for any state university? Politically, once they started getting accredited to offer bachelor level degrees they became increasingly more and more under attack. Even today, traditional institutions of higher education continue their stigmatizing attacks on non-traditional colleges/universities; Chicano-oriented efforts in higher education must still grapple with that stigma. For example, state colleges will not hire applicants for faculty positions from non-traditional universities, namely online PhD programs. There isn’t a rule, policy and/or law that keeps online degree holders out; it’s simply part of the high-brow culture found in the Academy, it’s the unspeakable truth, everybody knows but nobody will say, “We don’t hire those people.” Having served on a number of hiring committees, when it comes to reviewing applicants (to include Latino applicants) from online graduate programs, I know for a fact that many highly qualified Latinos are being passed over purely out of stigma for non-traditional learning and perhaps for racist reasons as well. Yet, here we are in the middle of a pandemic that forces state institutions of higher education to teach and conduct administrative business in this modality and no one is assessing the pros and cons of online learning—that dialog has been temporarily put on hold. To be sure, we all understand the impacts of the pandemic and rapid social change, but again the unspeakable truth is that we (in the Academy) were forced to make the shift to online teaching and learning overnight, yet the stigmatizing attacks on small private start-ups continues as well as on online degree recipients. The National Hispanic University (NHU) had similar beginnings as the InterAmerican College and the Colegio César Chávez. NHU became fully accredited, but regardless of a number of sizeable corporate donations from Silicon Valley funders, they could not establish long-term “hard funds” (secure ongoing perpetual funding) to underwrite the university as required by the accreditation body. At the point where the accrediting agency, the Western Association of Colleges and Universities or WASC, threatened to take away their accreditation (in essence close the university), NHU sold their “accreditation medallion” to a Brazilian Corporation claiming to be “Hispanic” based in Baltimore, Maryland, in turn, stripping the Chicanismo right out of the university. This is one of the important lessons learned. Conversely and to the point a number of online colleges/universities such as Walden University, Western Governors University, University of Phoenix, Grand Canyon University, United States University, and National University, all begun in non-traditional settings, are doing a better job at graduating Chicano/Latino students. Concurrently, the pandemic has caused and is causing a cognitive shift (perhaps even a paradigm shift) in how higher education is viewed and assessed by students and their parents in daily life. Students and parents alike are questioning the value and the content of higher education. Moreover, the statistics for the number(s) of PhDs earned by people of color in aforementioned online graduate programs outweighs that of UCLA, Stanford and Harvard and all other universities for that matter. That being the case, why should Latinos continue believing and supporting traditional models, a la brava, as they are not serving us in the manner in which we support them? Financially speaking, if we were to take the case of California taxes and say take the state taxes Latinos contribute to the State’s budget and invest those funds in the non-traditional colleges/universities that are producing Latino degree holders, the meaning of a college education will radically change and this is where we could be headed. I find it ironic that during a pandemic lockdown, Mt. Angel, Oregon, is calling out to me in this way, a small German-American town with a grand annual Ocktober Fest, we’ll have to add Corona, Modelo and Dos Equis beer to the festival. In 1973 Mt. Angel and the physical site of the Colegio César Chávez became the basis for an ABC television series about a town that becomes the nucleus for a post-apocalyptic community that returns to Medieval ways of technological applications. I am so moved by new paths of discovery about the efforts of early pioneers that planted Chicanismo in Mt. Angel that I am taking all I know about technological applications (far beyond online teaching and learning), and in reflecting on the experiences and lessons learned from the founding of the Colegio César Chávez, and drafting a new pandemic driven paradigm for restructuring higher education. The spirit of Chicanismo that once captured this obscure historic small rural setting demonstrates the power of an idea, the idea of a Chicano college, will not die; it simply provides a wretched experience to learn from. César’s favorite saying about education was a quote from Alberto Einstein, “Imagination is more important than knowledge!” and that is certainly at work here. What you need to know is that another Chicano college is on the horizon, one whose premise is to move Chicano students from dependence to interdependence to independence as community activists based on service and service-learning. Once accreditation was realized and as part of the sale of the InterAmerican College, we agreed with WASC (the accreditation body) on two points. The first point is that we would keep the Chicano vision statement intact, and the second point was that we would not start another college in the region for at least seven years. Well, the time is up. The InterAmerican College has already submitted a new application to the Bureau of Higher Education.  Armando Arias is a professor and founding member in the division of Social and Behavioral Sciences and Global Studies at CSU Monterey Bay and a frequent contributor to this magazine in his column, Chicano Confidential. He is the author of Theorizing César Chávez New Ways of Knowing STEM, published recently by Somos en escrito Literary Foundation Press, Berkeley, 2020, in which he shares a critical analysis of STEM studies, portraying his views as César Chávez would have had he gone on to earn a doctorate in science. He has served as a start-up team member for more than a dozen new universities in the U.S. (mostly in Aztlán) and consulted on the founding of new universities in Japan, Mexico, Europe, and Africa.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

||||||

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed