|

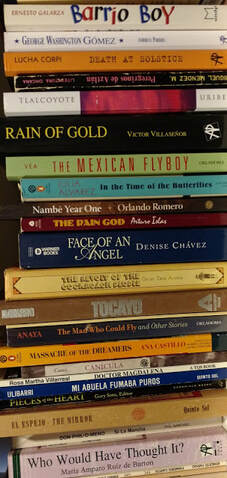

Rinconcito is a special little corner in Somos en escrito for short writings: a single poem, a short story, a memoir, flash fiction, and the like. El Rey del Batey |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed