|

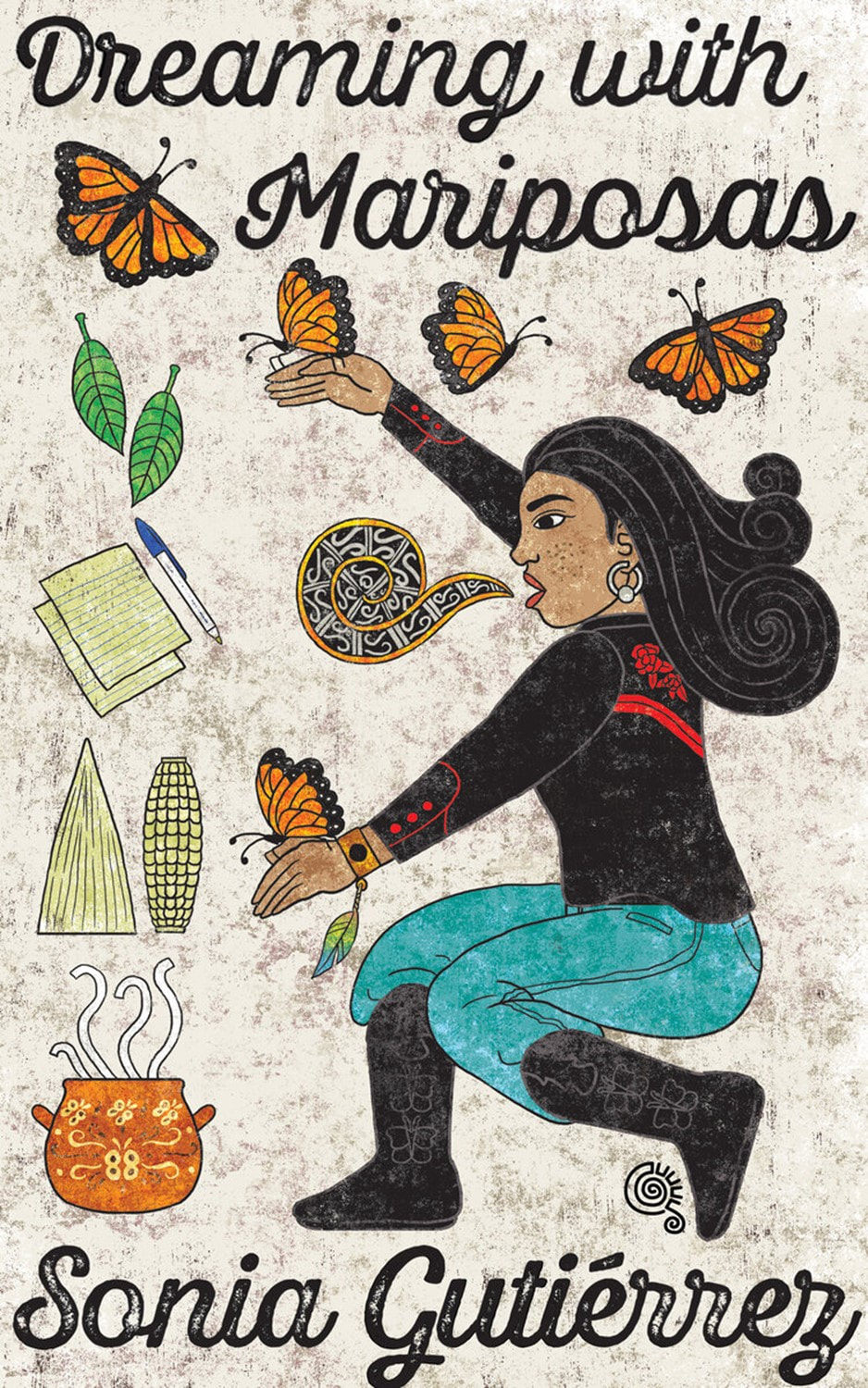

FlowerSong Press in McAllen, Texas, recently published Sonia Gutiérrez's novel, Dreaming with Mariposas, winner of the Tomás Rivera Book Award 2021. Read an excerpt below. Order a copy from FlowerSong Press. Our Doctor Who Lived in Another Country Whenever Paloma, Crucito, and I got so sick Mom couldn’t heal us with her herb-filled cabinets, an egg, or Vaporú, we had to wait for the week to hurry up, so Dad could take us on a trip to visit our doctor who lived in another country. We crossed the border to a familiar place called Tijuana, Baja California, México. Estados Unidos Mexicanos—the United Mexican States—said the large shiny Mexican pesos in Spanish. With her miracle stethoscope, our doctor’s Superwoman eyes and Jesus hands always found where the illness hid. As our father drove into Tijuana, the city looked like an expensive box of crayons. Fuchsia and lime green colors hugged buildings. Dad parked our shiny Monte Carlo the color of caramelo on the third floor of a yellow parking facility, and we walked down a cement staircase and crossed onto Avenida Niños Héroes. Then, we went up peach marble stairs and entered our doctor’s waiting room. On the weekends, patients from faraway cities like Los Ángeles and San Bernardino came to see La Doctora. Judging from the looks of some of the patients’ faces, they were there to see the doctor’s husband, who was a dentist. They made the perfect couple—the doctor and the dentist—for both their Mexican and American patients. The doctor, a tall woman with smoky eye shadow, looked directly into her patients’ eyes when she spoke. Not like some American doctors in the U.S. who didn’t look at Mom because she only spoke Spanish. On one of those doctor visits, I heard the dentist, a tall, burly man with a mustache that looked like a broom, speak English on the telephone with a patient. “John, you need to come in, so I can take a look at your tooth.” Another time I saw an elderly gringo, waiting for his wife, seeking the dentist’s services. That’s when I realized the other side was expensive for them too. When we were done at the doctor’s office, our next stop was El Mercadito on the other side of the block on Calle Benito Juárez. Churros sprinkled with sugar and cinnamon in metal washtubs rested on the shoulders of vendors. Fruit cocktail and corn carts were closer to the sidelines of streets, so passersby could make full stops and buy their favorite pleasure bombs to the taste buds. During summer visits to Tijuana, Paloma ate as much mango as she wanted because fruit was affordable in México. My weakness was corn. And even if I felt sick, I always looked forward to eating a cup of corn topped with butter, grated cheese, lemon, chili powder, and salt. Mexican corn didn’t taste like the sweet corn kernels from a tin can—Mexican corn tasted like elote. Approaching El Mercadito, dazed bees were everywhere. Mother warned us about not harassing bees. Because according to Mom, bees were like us—like butterflies. “Without bees, our world would not be as beautiful and delicious. Bees are sacred, and without them, we wouldn’t exist. Paloma and Chofi, please don’t ever hurt bees,” Mom said as we walked by our fuzzy relatives and nodded in agreement. The smell of camote, cilacayote, cajeta, and cocadas added to the blend of enticing smells at the open market, where we roamed with buzzing bees peacefully. Colorful star piñatas and piñata dolls of El Chavo, La Chilindrina, and Spiderman hung along the tall ceiling, and the familiar smell of queso seco filled the air heavy with delight. Wooden spoons, cazos made of copper, molcajetes, loterias, pinto beans, Peruvian beans, and tamarindo provided such a wide selection of merchandise vendors didn’t have to fight over customers. Politely, they asked, “What can I give you?” or “How much can I give you?” as we walked by. In Tijuana, street vendors sold homemade remedies for just about anything imaginable. “This cream here will alleviate the itch that doesn’t let your feet rest,” and “For a urine infection, drink this tea,” vendors hollered. And then there were the funny concoctions, for which even I, a girl my age, didn’t believe their miracle powers: “For the loss of hair, use this cream that comes all the way from the Amazon Islands.” Hand in hand with our familia, Paloma and I walked the streets of Tijuana with our sandwich bag full of pennies and nickels. We gave our change to children who extended their little palms up in the air. Mom would take a bag full of clothing and find someone to give it to, which I never understood, because most people on the streets dressed just like us, from the pharmacists to children wearing school uniforms. Once, when we were walking in Tijuana, Paloma and I saw a man with no legs riding what looked like a man-made skateboard instead of a wheelchair. Our eyes agreed; the man needed the rest of our change. Besides the rumors about Tijuana being a dangerous place, nothing ever happened to our car or Mom’s purse. In Tijuana, doctors had saved Crucito’s life because my parents knew, if they took Crucito to a hospital in the U.S., he might not come out alive because American doctors wouldn’t try hard enough for a little brown baby like my little brother. In Tijuana, our parents spoiled us with goodies and haircuts at the beauty salon. And I felt bad for Americans who couldn’t afford a doctor and didn’t have a good doctor or a dentist like ours in El Otro Lado—on the Mexican side. Pobrecitos gringos. Launderland “. . . Girls--to do the dishes Girls--to clean up my room Girls--to do the laundry Girls--and in the bathroom . . .” —The Beastie Boys, “Girls” Because we couldn’t afford a fancy steam iron, Mom was very practical. Instead of using a plastic spray bottle, she sprayed Dad’s dress shirts, including other garments with her mouth. She gracefully spat on each garment lying on el burro. Ironing was always an all-nighter that seemed endless and agonizing. I hated ironing Dad’s Sunday dress shirts—or anything, requiring special care and Mom’s supervisory instructions. There were two chores I hated most about being a girl: ironing and washing someone else’s clothes. The piles and piles of Dad and Mom’s dress clothes on top of our clothes seemed endless. (Thank God Father worked in construction or else long sleeve dress shirts would have added more to the pile). As soon as Mom started setting up el burro—the ironing board—in what should have been half a dining room, but instead we used as a bedroom, I began my whining. “Mom, but why do Paloma and I have to iron Dad’s clothes?” “¡Ay Sofia! You’re so lazy!” “It’s just that I don’t understand. I don’t wear Dad’s clothes. Why us?” “Sofia, are you going to start? That mouth! ¡No seas tan preguntona! You always ask too many questions! You always talk back! That tongue of yours. Where did you learn those ways‽” When I nagged, my mother’s facial gestures expressed her disappointment, and she turned her face away from me. What had she done to deserve such a lazy daughter like myself? With a cold bitter laugh, Mom responded, “Because he’s your father,” which I never understood. Having to live in apartments also meant we needed to fight over laundromat visitation rights. If anybody left their clothing unattended and the dryer or washer cycle ended, Paloma had to spy to check if anyone was coming, and I’d quickly take out the clothing and place it on a folding table. I’d throw our clothes inside the washer or dryer, and then we’d run to our apartment; otherwise, we’d be washing and drying all day. When we moved from Vista to San Marcos, that’s when I noticed chores strategically favored the man in our family. For instance, we girls never carried out the trash like Dad—just heavy laundry baskets mounted with dirty clothes. To me, mowing the lawn didn’t look difficult at all. It looked super easy and fun. How to Mow the Long Green Grass By Chofi Martinez 1) Check the lawn for Crucito’s toys, Dad’s nails, and any other sharp objects, including rocks. 2) Add gasoline. 3) Turn the lawn mower’s switch ON. 4) Press on the red jelly like button several times. 5) Pull the starter a couple of times. 6) Push the lawn mower with all your human strength. If I could mow the lawn like a boy, at least I could be outside and listen to the singsong of finches, watch white butterflies flutter through the garden, greet and wave at neighbors passing by, and stare at the endless blue sky. But instead of Paloma and me mowing the lawn, Dad dropped us off at the laundromat on Mission Avenue next to the dairy to wash and fold everything from heavy king-sized Korean blankets to Dad’s dirty and not so white underwear. Bras and underwear were the most embarrassing garments to dry, especially when red stained or not so new underwear fell to the ground, while we checked the clothes in the dryer. If an undergarment accidentally fell, it’s not like we could ignore it and just leave it there when it was clear we were watching each other. For us, if someone looked at our bra or underwear, it was as if they were looking at our naked bodies. It was equivalent to watching feminine hygiene commercials in front of boys or even worse—Dad. Oh my God! ¡Trágame tierra! Sometimes, when we barely had enough quarters and single dollar bills to spare in our imitation Ziploc bag, I’d window shop at the vending machine with its snacks and cigarettes then stare and admire the package labels with the bright oranges and mustardy yellows. While we waited for the washer to end, we sat on the orange laundromat chairs (bolted to the ground in case anyone tried to steal them, I figured). My eyes wandered—at the graffiti, the announcements, the tile floor that needed a broom and a mop, the Spanish newspapers with the sexy ladies with their back to the readers wearing a two piece—a thong and high heels and the constant drop off and pick up of wives and daughters. Swinging my feet back and forth out of boredom, I stared at the dryer’s circular-glass door with the thick-black trim, where garments would slowly go round and round and round and round, painting a picture of a vanilla and chocolate ice cream swirl, which was like meditating in front of a TV screen. Another dryer gave form to a motley of colors from the palette of Matisse’s bright yellows, blacks, oranges and greens Ms. Watson, my art teacher, had lectured on. And then, the dryer came to a full stop, and the colors—the burgundy red and thorny pink roses and the stoic lion—on heavy blankets took their true forms in need of folding. Our Dream Home Mom and Dad were always working for our dream house. In his early twenties, dressed in slacks and a tie, José Armando, our real estate agent, came to our apartment and talked to my parents about becoming homeowners. He sat patiently for what felt like hours translating endless paperwork. José Armando, Tijuana born with Sinaloa roots, grew up in Carlsbad, “Carlos Malos.” He smelled like a professional, and the heaviness of his cologne and starchy clothes filled our small kitchen and living room long after he was gone. Our real estate agent felt like familia. “Helena and Francisco, the contract states that if you complete all the renovations within a year, the bank will approve the loan. You can move in now, but the house is not in living conditions.” “But Jose Armando, I’m sure you’ve heard stories--what if the gringo doesn’t keep his promise?” Mom asked our real estate agent. “Helena, please trust me. Mr. Stoddard is a good man and will not back out of the deal because he signed the contract,” José Armando assured Mom the owner would follow through. “You know Francisco more than I do. Your husband is going to make the house look like a palace—like your dream home. Helena, the property even has a water well. You can add the roses, calla lilies, and fruit trees you’re looking for in a property. And, most importantly, you won’t have to commute from Vista to San Marcos anymore.” Where Dad and Mom came from, waiting periods to build a house didn’t exist; people didn’t need permits to build a home made from adobe or blocks. In the U.S., however, my parents had to settle for a fixer-upper Dad could mend in no time with the help of family and friends. When José Armando finally struck a deal with the owner, it took Dad a whole year to claim the house on 368 West San Marcos Boulevard as our own. After Dad came home from working construction all day, he’d work at home. Mom must have had sleepless nights when Father agreed to buy our first house. That’s because Mother didn’t see what Father saw. We would have a street number to ourselves, 368. The first days at 368, Mom refused to eat in the kitchen, and how could she eat in there? How could her children eat in that thing Dad called kitchen? Yes, the house included a small stove, but cockroaches were baking their own feasts in the oven. Dad imagined a swing set for Crucito in the backyard’s green lawn. But Mother had heard the neighbors walking by say the backyard turned into a swamp during the rainy seasons. Dad imagined a one-foot swallow lined with miniature plants that would keep the water moving to the large apartment complex next door. But Mom saw the swamp at our feet. Dad imagined the pantry and mom’s new wooden cupboards. But Mom saw mice and cockroaches. Lots of cockroaches. Mom saw the faded dilapidated and peeling mint green paint. Dad saw a new wooden exterior and a fresh coat of paint. Our new but old kitchen was infested with silky brown cockroaches—the thin kind that matched the plywood. Underneath the crawl space lived the critters, and at night, big roaches squeezed and welcomed themselves in through both the front and back door to drink water and eat crumbs. Paloma and I, in our superhero capes, made from black trash bags, became Las Cucaracha Warriors de la Noche and ran after the cucaracha bandits. We routinely turned off the lights, and then at about ten o’clockish, Mom turned on the kitchen lights, and Paloma and I charged at them. While they scattered everywhere, we all took our turns killing the horde of nightly visitors. The pest problem at 368 went away with endless nights of Raid attacks and hot water splashing. Paloma and I even conquered our cockroach phobia and squished cockroaches with our very own index fingers. The master bedroom had seven layers of dusty carpets pancaked on top of each other. The wooden floor in our living room held itself together miraculously—we were always careful to wear shoes to prevent any splinters from pricking our bare feet. When we finally settled into our new home, one Saturday morning Paloma and I still in our pajamas were arguing over who would have to sweep and mop before our parents got home from work when suddenly we found ourselves shoving and wrestling each other. And then with a big push, the unexpected happened. I flew through the wall. “Oh my God, Chofi! Look what you did!” “Look what I did? You pushed me, Mensa!” Paloma and I had to reconcile immediately to cover up the crime scene. When Dad got home later that afternoon and walked through the hallway to inspect our chores, he demanded an explanation, “¿Y este pinche sofá? ¿Qué está haciendo aquí?” Chanfles, we thought as our eyes placed the blame on each other. Dad gave us the mean Martinez Castillo stare with the white of his eyes showing that always worked, shook his head, and stormed out of the house because Dad knew he had to replace all the house’s old plywood with new drywall. Our idea of placing a love seat in front of the hole to cover it up didn’t work. Our fear for our father’s punishment turned into giggles and then uncontrollable laughter. Poking at each other’s ribs and yelling at each other, “It’s your fault!” and “No, it’s your fault!” we almost peed our underwear. We laughed at the hole in the wall, the sofa that barely fit in the hallway that must have looked ridiculously out of place in our father’s eyes, and at our new but old house facing the boulevard. Strangers driving by honked or waved and gave Dad a thumbs up when he worked on our house on the weekends. We were living in Father’s dream home, and we were happy. José Armando, our real estate agent, was right—Dad fixed our house, and Mother created her garden of dreams, where Dad and Mom planted hierbas santas. Orange, avocado, peach, cherimoya, guava, and purple fig trees. And native yellow-orange, deep-purple, and rose-colored milkweeds for our butterfly relatives who passed by and travelled south to Michoacán, our parents’ homeland. One day we would follow them if Mom and Dad worked hard and saved enough money. One day. The Guayaba Tree In San Marcos, our backyard smelled like Idaho. The familiar smell of manure from the Hollandia Dairy on Mission Avenue lingered in our backyard. Months before the guava tree joined us at San Marcos Boulevard, Mom took free manure from the dairy for our garden and prepared the earth with water. Even if we already had a few trees, Dad and Mom talked about the trees and plants with special powers that would join our family. Next to the guayaba tree’s new home, the apricot tree had already joined us, and now it was the guava tree’s turn to step out of its black plastic container and to spread its roots and branches. At the end of the week with their Friday paycheck, Mom and Dad’s eyes were set on an árbol de guayaba. Right after work Dad drove us to the northside of San Marcos on the winding road to Los Arboleros, the tree growers’ ranch on East Twin Oaks Valley Road, to buy the perfect tree for our backyard. As we approached a dirt road leading to the Santiago property, Don José in his sombrero and red and yellow Mexican bandana tied around his neck waved at us. At his side, two large Mexican wolfdogs with imposing orange eyes barked at us as we approached the nursery next to their house. “Paloma and Chofi, be careful with Don Jose’s dogs.” “Okay Ma,” we answered in unison. “Buenas tardes, Francisco and Helena. Don’t worry, Señora Helena. My calupohs don’t bite unless they smell evil. They scare off the coyotes that want to get into the chicken coop. Last week a red-shouldered hawk snatched one of my María’s chickens in broad daylight.” Don José’s dogs, Yolotl and Yolotzin, sniffed our stiff bodies while I prayed to San Jorge Bendito: “San Jorge Bendito, amarra tus animalitos . . . .” Yolonzin sniffed and licked my hand. Thankfully, Don José’s calupohs remembered us; we were in the clear. “If you need anything, holler at me. I’m going to water the foxtail palm trees on the other side.” At Don José and Doña María de la Luz Santiago’s small ranch, Paloma and I were careful not to step on rattlesnakes. We walked through the rows of small trees in 15″ containers and played with sticks next to a large flat boulder with smooth holes. I filled the holes with dead leaves and dirt and mixed it with a stick. “Paloma, let’s ask Don Jose about the holes on this large boulder. How do you think these holes got here?” Paloma shrugged her shoulders and signaled with her head to get back. With the calupohs following us, we found Mom and Dad still deciding on a tree and a crimson red climbing rose bush. “But Pancho, look how green the leaves look on this one!” “Yes, Helena, but look at this one. It has a strong tree trunk.” “Pancho, this one has ripe fruit! Smell it, Pancho. With time, this one will be strong too.” “You’re right, Helena. We can take the one you want. Let’s pay Don Jose and get going before it gets too dark, so we can plant our tree today.” “Yes, Pancho, it’s a full moon!” “Paloma and Chofi, I’m glad you’re both back. Go look for Don Jose, and tell him we’re ready to pay.” Paloma and I ran to look for Don José. On our way to find him, I remembered we needed to ask him about the holes on the boulder. “Hola Don Jose. My mom and dad are ready to pay.” “Let’s go then.” “Don Jose, we have a question for you. We saw a big flat rock on your property, and we’re wondering how the holes got there.” Don José cleaned his sweat with his bandana and gave us a pensive look. “Those holes. Well, Chofi, as you may know, this land you see here from Oceanside all the way to Palomar Mountain and beyond was inhabited by Native people. Women sat and pounded acorns on metates like the one you saw and made soup and other foods. You can only imagine how many years it took for those indentations to leave their mark and to withstand time. Those women, Chofi and Paloma, left their mark.” “Oh, wow, Don Jose. That’s why the road is called Twin Oaks Valley Road? It’s a reference to Native people’s trees, who lived in this area?” “Yes, Chofi and Paloma. Native people still live on these lands—in Escondido, San Marcos, Valley Center, Fallbrook, Pala, and Pauma Valley and beyond. Ask your U.S. history teacher about the people who inhabited these lands. I’m sure they can tell you more.” “Thank you, Don Jose. I’ll ask.” Dad and Mom paid Don José, and off we went to plant our guayaba tree. With our guava tree sticking out of the window in the Monte Carlo and lying on Paloma, Crucito, and me in the back seat, Mom was all smiles and kept glancing back. “Pancho, please drive slowly and turn on your emergency lights. Children, hold onto our tree carefully.” “Don’t worry Helena. Two more stop lights, and we’re almost home.” Dad agreed to Mom’s pick because he knew she loved guayabas—all kinds. This time they chose the one with the two guayabas with pink insides, which wasn’t too sweet and just about my height. I preferred the bigger trees at Los Arboleros. Why couldn’t we get bigger trees? Mom and Dad always chose the smaller trees because those were the ones we could afford, and plus we didn’t have a truck like our neighbor Don Cipriano’s, but maybe we could borrow it next time. As soon as we arrived home, Dad cut the container down the middle with a switchblade, and Mom pushed the shovel down with her right foot and split the earth. “¡Ay, ay! ¡Ay Pancho! Be careful with the tree’s roots. Here, grab the shovel. Let me hold onto the arbolito.” Dad dug the hole, exposing the dark brown of the earth as two pink worms shied away from the light. “Dad, can Crucito and me get the worms, pleaseee?” “Hurry up Chofi and Cruz. Go ahead. Your mom and I want to plant the tree today.” “Okay, Apá!” While I carefully took the worms from their home, Mom held the guava tree as if she held a wounded soldier and whispered to the tree, “Arbolito, don’t worry. You’re going to be safe here. I’m going to water you when you get thirsty and take care of you—we all will.” “Pancho, one day we’re going to make agua de guayaba.” “Sí, Helena, we’re going to make guayabate like the one my mom used to make. It was so good!” “I bet it was, Pancho. To prevent a bad cough, my mom used to give us guava tea to fight off the flu.” “Helena, did you know guava leaves are also good for hangovers?” “Ay Pancho. ¿Qué cosas dices? Let’s get this tree planted.” From the dried-up manure pile, Dad mixed the native soil and compost and pulled the weeds. As Mom placed the rootball above the hole, they both looked for the guava tree’s face and centered the tree on top of the hole. With the shovel, Dad poured the dirt around the tree. Mom took the shovel from Dad and pounded softly on the dirt surrounding the guava tree, making sure they left the edge below the surface. Next to the apricot tree with a woody surface, the small guava tree with tough dark green leaves would be heavy with fruit one day for our family, our neighbors, and friends. Dad went looking for a canopy for the young guava tree to protect her from winter’s threatening frostbite, and mom stood in the garden, admiring our new family member. It was time to return the worms to the earth; they were so tender but so strong. I made a little hole with my hand, placed the worms inside, said thank you to the worms, and covered them with dirt. The guayaba tree would make a perfect home.  Sonia Gutiérrez is the author of Spider Woman / La Mujer Araña (Olmeca Press, 2013) and the co-editor for The Writer’s Response (Cengage Learning, 2016). She teaches critical thinking and writing, and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. FlowerSong Press in McAllen, Texas, recently published her novel, Dreaming with Mariposas, winner of the Tomás Rivera Book Award 2021. Her bilingual poetry collection, Paper Birds / Pájaros de papel, is forthcoming in 2022. Presently, she is returning to her manuscript, Sana Sana Colita de Rana, working on her first picture book, The Adventures of a Burrito Flying Saucer, moderating Facebook’s Poets Responding, and teaching in cyberland.

0 Comments

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed