“The Mothers of Llullaillaco”by Julia Aguirre I heard the story of The Children of Llullaillaco, and the thousands that preceded and followed them. I wept for them, though it was hundreds of years ago, and I was angry for their bodies, kept from their families in life, in death, and hundreds of years after. But in between all that, I thought of their mothers. The mother of El Niño, what she might have felt, when her baby was taken that day. She always knew he was beautiful, from the moment she held him in her arms, he was the most beautiful thing to her, and he would have been even if the elite declared him ugly. But they declared him beautiful. Was it because she looked at him like he was? If that was the reason, would she have taken it all back, treated him as a monster, if just to let him live? They say that the families of the poor should have been honored, honored that their beautiful peasant children looked like they could be the children of kings, honored that their precious sons and daughters would be sacrificed, to save the true royal blood that graced the earth. How could you not be grateful, they said as they bound the children like slaves, that we get to kill your child? The mother was not grateful. Another may have been able to lie to their children, to fake a smile until they were out of sight. He is just a child, just a baby, and she cries, she screams and fights even when they beat her into the ground. She knows she might not see tomorrow for her outburst, but she will not let her baby go, no, not without him knowing that this is wrong, that she didn’t want this, that he should have lived and been happy. She will take his place, she will carve out her own heart for the gods, place herself on the altar to appease the wealthy who crave the blood of her son. El Niño cries, and in a moment, he is gone. His mother is not dead, not yet. But she wishes she was. In five hundred years she will be called a barbarian by white men who steal from the grave of the child she lost. A woman who knows nothing will call herself El Niño’s protector and mother, and keep him from his true family. The mother of Llullaillaco will find comfort will be knowing her son died knowing she loved him, and that knowledge made him fight, fight until his very last breath, even as the wealthy dug drugs between his lips and forced him to chew, even as they fed him meat so he felt like a king in those last moments, with the cold unforgiving mountain suffocating him, even with his mind swirling frantically, he knew he had to get back to his mother’s love, that she didn’t want this. He died knowing this was wrong. There were other children, who died a little more peacefully, perhaps, and there were others who lived safe and sound. I imagine another mother of Llullaillaco, wrapping her arms tightly around her ugly, royal-born child, who would have been sacrificed if El Niño had been ugly too. She does not want to watch, but she does, as El Niño fights for his life, his ribs breaking against ropes that tie him down as he tries to get up. She does not weep. She will not, until later, when her baby is asleep. She will cry and thank the gods for giving her this ugly child. And deep down, she will hate herself all the same. If ever there is a day her son grows, and is horrified by the altar and the blood on his mother’s hands and the drugs and the ropes, she will scream and beg his forgiveness, tell him she had no choice, that she was a monster, yes, she would be called a barbarian by the white men who dug up bones that didn’t belong to them, but she loved her son, loved him enough to kill another child if it meant keeping him safe.  Julia Aguirre is a 24-year-old woman living in Texas. She graduated with her bachelor’s degree at Brigham Young University. She majored in English and received a minor in Spanish. Her focus as a student was on creative writing, and she hopes to one day be a full-time novelist and part-time writing professor for university. Julia Aguirre is part Mexican, part Native American, and part white. Her bisabuela immigrated to the US with her parents when she was very young. With each generation, the love and traditions in the family continues to live on, and Julia has found more ways to reconnect with her ancestors through her writing. This is her first submission to a magazine. She plans to attend graduate school to receive her MFA in creative writing. Until then she will do what she does best- write until the ink runs out.

0 Comments

A Cuban Soap Opera Remakeby Matias Travieso-Diaz and Eloy Gonzalez-Argüelles [I want to speak, I want to speak, tell everyone Albertico Limonta is my grandson, the child of my oldest daughter Maria Elena.] Don Rafael del Junco’s silent litany in El Derecho de Nacer by Felix B. Caignet In mid-2047, the Instituto Cubano de Radio y Televisión (Cuban Institute of Radio and Television, or CIRT), received a proposal for a revival of the 1948 radio soap opera El Derecho de Nacer (The Right to be Born) by the Cuban radio writer Félix Benjamín Caignet Salomón. At the time, El Derecho, as it was called, swept Cuba by storm, and then spread to all of Latin America in a run that lasted over fifty years. It was regarded as one of the most influential soap operas of all time, and had been the subject of numerous radio, television and movie adaptations. The revival (in the form of a TV series to be aired in Cubavision) was to start in April 2048 to coincide with the centenary of the original radio broadcast. José (“Pepe”) Cubero, a brilliant movie and TV producer and director, was the proponent and strongest defender of the project. He acknowledged that the 1948 soap opera would have to be modified a bit to make it consistent with the culture and politics of twenty-first century Cuba, but felt the changes would be small and well within his creative abilities. The proposal met opposition from some of the most orthodox members of the Communist Party. They claimed that the original story was rife with the type of bourgeois, capitalistic ideology that had been eradicated after almost ninety years of Socialist rule. Other opponents, more practical, pointed to the chronic economic crisis that bedeviled the island with words like these: “Anything we broadcast must encourage the Cuban people to work harder, make sacrifices, concentrate on rebuilding the economy in the face of the heartless Yankee blockade. El Derecho is a frivolous, escapist diversion that would get us sidetracked from our mission. And it will run for many months, compounding the damage.” The matter was kicked upward to land on the lap of Miguel Diaz-Canel, who had been President and First Secretary of Cuba’s Communist Party for almost thirty years. He was in his mid-eighties and getting ready to step down, so he was in no mood to mediate in ideological disputes. He ruled: “Let Pepe Cubero come up with a proposed screenplay and give it to the President of the CIRT and the Minister of Culture. Let those guys decide what changes to the screenplay are required to render it acceptable, make those changes, and run with it. Don’t bother me with this shit again.” The Minister of Culture, Haydée Alonso, who had studied in Paris, quoted Sartre, and prided herself on being open-minded and liberal (within the ideological bounds of the Party), was enchanted with the idea of a revival of El Derecho, so she was inclined to give Cubero a relatively free hand. This was good news to Cubero, although no one else liked Haydée. No one forgave her for her unpatriotic preference for smelly Gauloise cigarettes that stunk up the studio, and that she did so “in the land where the best tobacco in the world used to be grown.” The CIRT President, Danylo López, was an old, dried-up bureaucrat concerned mainly with toeing the Party line and avoiding controversies, and was not amenable to letting Cubero get away with much. Torn between polar extremes, development of the new version of the soap opera proceeded in painful fits and starts. The first bone of contention was the character of Don Rafael del Junco, the villain of the story. Everyone agreed that Don Rafael, a haughty unscrupulous landowner, was a proper embodiment of the pre-Revolutionary capitalistic class. However, at the end of the original 314 episodes, Don Rafael reconciled with his daughter and grandson, and ended up being presented in a somewhat favorable light. “We have to change the ending” argued Danylo. “There can be no redemption for the enemies of the people.” Cubero reluctantly agreed to modify the end of the series so that Don Rafael got his comeuppance. He was hoping against hope that by the time the last episodes were filmed Danylo would have changed his mind. Then there was María Elena, the daughter of Don Rafael and mother of the hero of the series. Again, everyone agreed that she showed courage in refusing to have a late term abortion and insisting on giving birth to her illegitimate child. However, in the original series she sought shelter for her grief in a convent, where the nuns and other members of the community treated her with compassion and understanding. Danylo was loath to include any episodes that praised religious people. “Religion is the opium of the masses, and the State must not condone it in any manner.” Cubero had to change the script to have María Elena become a sort of hermit, seeking solace from the apparent loss of her child on a deserted shore. That in itself was problematic, since Cuba had implemented an internal passport system that was rigidly enforced. In the new Cuba, there was nowhere to hide. At the end, this discrepancy was allowed as poetic license, hoping it would not be noticed by anyone who had the power to object. In the original El Derecho María Elena leaves her newborn baby boy in the care of her once wet nurse, the black María Dolores, who saves the infant from being slain on orders from Don Rafael, manages to give Don Rafael the false impression that she and the baby are dead, and escapes with the infant to a remote village. There, she raises the boy as her own child, naming him Alberto (“Albertico”) Limonta. One salient and recurring problem was the relationship between “son” and “mother,” due to the fact that María Dolores claimed he was her son, even after his infancy. Yet, the actor chosen by Cubero to play Albertico, Ontario (“Guapito”) Ledesma, was white. Very white. Blondish. On the other hand, the lady portraying María Dolores was black, as stipulated by Caignet in the original soap opera. Coal black. No one seemed to find the discrepancy odd except for Haydée, who said that the role of María Dolores seemed taken out of Gone with the Wind. Her remark was met with a deadpan silence, for nobody in Cuba remembered or cared about old Yankee movies. The racial disparity problem did not fully surface at first, because the boy who played Albertico as a child had a darker complexion that made his relationship with María Dolores more credible. But later on in the show, when Ontario assumed the role of 25-year-old Albertico, María Dolores’ claim that he was her son began ringing hollow. Different suggestions were considered: darkening Ontario’s skin with blackface make-up like Laurence Olivier in Othello, other things of that nature. Haydée opposed them all, because, she said, it was not impossible that Albertico could still be María Dolores’ biological son. So, things were left unchanged. There was one scene, however, when the script called for older Albertico to run up to his mother and say, “Mamá, I love you so” as he hugged the black woman. The scene had to be redone many times because the crew in the studio—and later on, even Albertico and María Dolores—could not control their laughter. In the end, the scene was filmed as it was and prompted sarcastic comments among the viewers once aired. Much was done in the original series to highlight the discrimination and ill treatment that both María Dolores and Albertico endured on account of her race. Danylo liked that and wanted to accentuate the criticism of the racist society that existed in the country before the Revolution, but was opposed by Haydée, who warned not to overdo that aspect of the plot. “Remember, Danylo,” she said, “there are still people left in this country who believe blacks are inferior, although they won’t openly admit to it. There is no point in rubbing their noses on our commitment to equality among the races.” At the end, Danylo carried the day. Albertico, who was white, would be repeatedly abused and discriminated against for having a black mother and being a mulatto. In one scene intended to bring more “realism” to the story, a classmate of Albertico has a fight with him and calls him an “hijo de puta” (a bastard), not an uncommon insult in Spanish. Danylo objected to the use of such foul language, as it was not in keeping with Socialist morality. Haydée replied that this choice of words was used by ordinary people and prude sentiments to the contrary were a bourgeois atavism. A heated debate ensued and, at the end, Haydée seemed to say that the language in the series should not be controlled by a “partido de hijos de puta,” which many people took to refer to the Communist Party. Haydée, however, swore that she had not said “Partido” but “partida,” meaning “bunch” or “group,” without any political connotation. Since no one could produce a definitive argument, the matter was dropped, along with the entire scene. Many episodes later, thanks to María Dolores’ innumerable sacrifices, Albertico manages to make it through the university and becomes a famous doctor. In the original version, Albertico gets to be rich and lives in comfort with his aging “mother.” Both Danylo and Haydée objected to this turn of events. Cubero was required to rewrite that part of the story to have Albertico live modestly, see indigent patients for free, and travel to Haiti to help treat the victims of a devastating earthquake. In the rewrite, Albertico returns to Cuba with a newfound social conscience, alert to the inequities of the capitalist society and committed to fighting them. Later in the series, Albertico is doing night duty at a public hospital’s emergency room when several injured people are brought in after a traffic accident. One of them is an old man who is bleeding to death. The victim’s blood type is AB negative, the rarest type, which is unavailable at the ill-equipped public hospitals of pre-Revolutionary times. Albertico, AB negative himself, gives a transfusion that saves the man’s life. The victim, who is no other than Don Rafael del Junco, recovers and as he convalesces, he invites his savior to come to dinner and meet his family. There Albertico meets Isabel Cristina, daughter of María Elena’s sister Matilde, and a budding romance blooms between the couple, unaware that they are cousins. Danylo was not in favor of retaining potential incest as part of the plot, and Cubero had to add another twist at the end of the story where it is revealed that Isabel Cristina is not the natural daughter of Matilde, but only an adopted one, eliminating another potential offense to Socialist morality. Don Rafael, now fully recovered, is one day taking a stroll near an outside market, when he spots an old black woman that he immediately recognizes as María Dolores, who he had written off as dead many years before. He follows the woman, overtakes her, and confronts her. María Dolores acknowledges that she and Albertico are alive and well, and rebukes Don Rafael for his cruelty. Cubero is asked to add language to the confrontation scene wherein María Dolores lists once again all the aristocrat’s misdeeds and concludes with a stirring pronouncement: “Beware, for your days are numbered. The people soon will hold you accountable for all the crimes you have committed against your family and against society.” Staggered by these revelations, Don Rafael returns home, where he promptly suffers a stroke (“derrame cerebral”) (a common mishap in soap operas) and falls into a coma. In the original version, Don Rafael stays in a coma for many months, burning with desire to impart the crucial news of the existence of his missing grandson to his wife and daughter, but is paralyzed and unable to speak. Here, however, science rather than politics interferes with the progress of the story. By 2047, a process had existed for years by which an artificial intelligence (AI) could accurately decode words and sentences from brain activity. Using only a few seconds of brain activity data, the AI can guess what a person is trying to say and translates it into a voice recording. The AI was commonly used throughout the world, including Cuba, to help people unable to communicate their thoughts through speech, typing or gestures. The existence of the AI technology rendered a crucial portion of the original version of El Derecho vulnerable to ridicule by the viewing public. There was no way Don Rafael could linger, speechless, for several months. Cubero and his creative team struggled with the problem for weeks and finally had to come up with a lame solution: Don Rafael suffers a “derrame cerebral,” but recovers almost immediately and, instead of bringing the existence of his grandson to the attention of everyone, has a change of heart and continues to cover up his earlier nefarious crimes by accusing María Dolores of theft and charging Albertico with complicity in the black woman’s schemes. Isabel Cristina, whose love for Albertico has not been diminished by Don Rafael’s accusations, alerts her boyfriend before the police can seize him, and Albertico escapes to a bitter exile in Tampa, where his mulatto identity subjects him to additional discrimination and mistreatment at the hands of the American imperialists. Meanwhile, María Dolores lingers in jail and ultimately dies of sorrow. From that point on, the plot of the revival diverges entirely from the original radio show. Albertico becomes a revolutionary hero and travels back to Cuba to take up arms in the mountains against the corrupt government. He alerts Isabel Cristina of his whereabouts and she joins him to continue, together, their fight for justice. Through one of his comrades, who knew Isabel Cristina’s parents, it is revealed that Isabel Cristina and Albertico are unrelated, whereupon the couple is chastely married in a civil ceremony conducted by a rebel leader. They are enjoying a brief honeymoon when they learn that Don Rafael has been killed in a terrorist attack against the Presidential Palace, where he was attending a reception. Albertico and Isabel Cristina kiss and hug each other, relieved at the evildoer’s death, and the series ends. As the first six episodes were filmed, José Cubero had increasing misgivings about the product he was going to set before the public. Technically, the series was as good as he was capable of putting together: photography, score (instrumental renderings of Cuban ballads going back to the 1800s), sound effects, customs, editing, were all first class. He had assembled a cast of experienced actors and actresses, with a famous Spanish TV personality in the role of Don Rafael. Much of the series was shot in locations selected for their beauty or historic interest. Artistically, though, Cubero felt he was doing a disservice to—actually, betraying—Caignet’s original work and regretted all the compromises he had been forced to make to get the project approved. As a way to hide his guilt, he made sure of the destruction of all copies existing in Cuba of the audio, TV and movie versions of the series, be they from Cuba, Puerto Rico, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Venezuela or Mexico. Cuban censorship saw to it that no written materials describing the 1948 series were available to the public. Since there was nobody alive who had listened to the original broadcast, Cubero felt confident that he would not be confronted by critics of the savaging he had been forced to perform on the original. Still, he went to bed the night of Tuesday, March 31, 2048 with a heavy heart, in anticipation of the premiere of the series the following evening. He tossed and turned in bed all night and, in the few minutes of actual sleep, was accosted by the image of a dapper slim man sporting a trim moustache and a mane of black pomaded hair, who appeared and disappeared before him making menacing gestures and repeating incessantly a single word: “Why!!?” The first episode of the new rendering of El Derecho de Nacer was shown on Cubavision at 9 p.m. on April 1, 2048. The show ran, Monday through Saturday, for 310 episodes, the last one playing in the spring of 2049. While initially garnering much public attention, interest in the series wore off quickly, so that the last episodes were seen by almost nobody. Many concluded that much of what was shown and said in the series was predictable and no different, except for its excessive duration, from other political indoctrination efforts by the government. José Cubero finished producing the last package of ten episodes and sought and was granted permission to take a short vacation abroad to recover from his massive effort. He was last spotted taking an Iberia plane bound for Madrid on April 15, 2049. He was never seen again.  Matias Travieso-Diaz was born in Cuba and migrated to the United States as a young man. He became an engineer and lawyer and practiced for nearly fifty years. He retired and turned his attention to creative writing. Seventy of his stories have been published or accepted for publication in paying short story anthologies, magazines, blogs, audio books and podcasts. Some of his unpublished stories have also received “honorable mentions” from a number of publications. A collection of some of his short stories, The Satchel and Other Terrors, is scheduled for publication in February 2023.  Eloy González Argüelles was born in La Habana, Cuba, and came to the United States in 1961. His studies culminated in a PhD in Romance Languages at the Ohio State University. He taught at Wheaton College (Norton, Massachusetts) and the University of Massachusetts (Harbour Campus) before moving to Washington State University (WSU), where he taught Spanish literature and literary criticism for 38 years. For ten of his last twelve years before retirement he was Chair of the Department of Foreign Languages and Cultures at WSU. His output includes a novel, a book on the chivalric novel, and articles in scholarly journals and conference presentations. Upon retirement he became an Emeritus Professor at WSU. La Sirvienta / The Maid |

| Gloria Delgado, born and raised in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, is the daughter of a Mexican father and a Hawaii-born Puerto Rican mother. She and her husband live in Albany, California. One of her stories, “Savanna,” was included in the Berkeley Community Memoir Project’s recently published collection, “A Wiggle and a Prayer.” This is her fourth story for “Somos en escrito.” |

**Painting of San Antonio de Padua, patron of the poor, by Micaela Martinez DuCasse, the daughter of Xavier Martinez, a well-known Mexican artist who spent much of his life in California. Ducasse also taught classes at Lone Mountain when Delgado was a student.

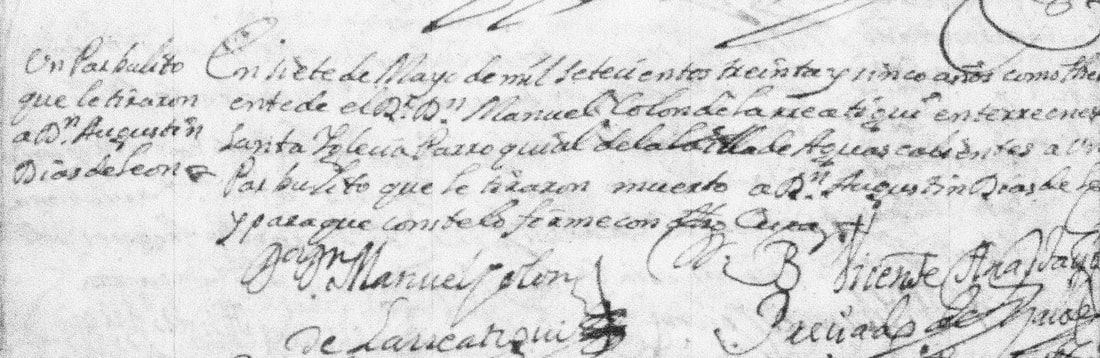

This story is a work of fiction based on historically documented events. All individuals with surnames, including their children, were real people; those without surnames are fictional.

In Mexico tens of thousands of residents, Indians, mestizos and españoles alike, died from intermittent plagues, smallpox, chickenpox, mumps and measles. At times there were so many deaths that the priests were too overwhelmed to comply with church regulations as to the proper listing of entries in the death records, able to note only the date of death and the names, if known, of victims who were interred on that date.

Don Augustín Diaz-De Leon’s child, Pantaleón, died in December 1747, eight months after the death of his father. Pantaleón was three years old. The youngest child, Augustín Miguel Estanislao, was born two weeks after his father’s death, on 11 May 1747. He survived into adulthood, eventually settling in Sierra de Pinos, Zacatecas, where he and Thadea Josepha Gertrudis Muñoz Tiscareño married.

Don Augustín’s widow, doña Maria Antonia Fernandez de Palos Ruiz de Escamilla and el alcalde mayor don Fernando Manuel Monrroy y Carrillo, (witness to the death of don Augustín as well as the executor of his estate) in September 1749 were granted a dispensation to marry. Don Fernando was a widower; his first wife was doña Juana Salvadora Jimenez.

Don Augustín’s father, el alférez (subaltern) don Visente Xabier Diaz-De Leon, was at this time the owner of the Hacienda de Peñuelas. Following the death of his first wife, doña Catharina Acosta, he married and raised another family with his second wife doña María Dolores Medina. Upon his death in April 1754 he left money (including 15 gold Castilian ducats) for his intentions, including 100 masses to be offered for the repose of his soul and for his servants, living or dead.

The ex-Hacienda de Peñuelas, still in existence, is one of the oldest haciendas in the Mexican state of Aguascalientes. Established sometime before 1575, Peñuelas predates the foundation of the Villa of Aguascalientes itself. This hacienda consisted of several self-supporting plantation-like communities staffed and farmed by resident Indians and slaves.

The Cathedral Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, originally known as San Ysidro Labrador, was initiated in 1704 and completed in 1738 by don Manuel Colón de Larreátegui, head of the Mitra de Guadalajara. Its northern bell tower was completed in 1764, the southern bell tower not until 1946.

Sources

All birth and death documents cited are from the following:

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints:

FamilySearch.com and other films on line.

The entry cited re the infant, the parbulito of this story, is from:

Mexico Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, Catholic Church Records

Parroquia del Sagrario, Asunción de Maria

Defunciones 1708-1735, 1736-1748

El Parbulito: Image 530 [Libro quatro de Entierros]

Montejano Hilton, Maria de la Luz:

Sagrada Mitra de Guadalajara, Antiguo Obispado de la Nueva Galicia, 1999

Rojas, Beatriz, et al:

Breve historia de Aguascalientes, 1994

Topete del Valle, Alexandro:

Aguascalientes: Guia para visitar la Ciudad y el Estado, 1973

Vázquez y Rodríguez de Frias, José Luis:

Genealogía de Nochistlán Antiguo Reino de la Nueva Galicia en el Siglo XVII según sus Archivos Parroquiales, 2001

A Story of the Fourth Crusade

--Memoir or Chronicle of the Fourth Crusade and The Conquest of Constantinople, Geoffrey de Villehardouin,

Translated by T. Marzials

When they arrived at the port, the other crusaders were not there. But Sir Robert and Eusebius dared not wait. Their brothers may have been arrested or shipwrecked or perhaps have had a change of heart. One way or the other, by now their plan was surely known to the Doge and the Frankish Barons, and there was no other recourse except to continue to Syria alone.

Sir Robert and Eusebius hid during the day in abandoned stone huts in the countryside or in caves. In the dead of the night, they stole food from the villages and farms. Soon every night seemed like the night before and only the changing moon told them that time was indeed passing, and they were still living men and not wandering spirits.

One night, they discovered an offering of food at the entrance of a Muslim village. Or so they thought. The remains of a slaughtered sheep hung on a post. Not the entire carcass, just the heart, liver, lungs, and kidneys. Blue glass amulets were hung next to the entrails. Pieces of paper with Arabic writing were littered on the ground as well.

Eusebius was wary of the food offerings, but not Sir Robert whose mind was filled with fantastical musings about how the villagers must think they were spirits or wayward angels. When they found similar meat offerings at the entrance of every village, the knight was more convinced than ever that this was a sign from God.

When the third full moon had arrived, they came upon a stone marker with three crosses. They were now in Christian lands. Giving thanks to God, they slept for the remainder of that night and greeted the sunrise once again.

“The infidel armies must have marched through here on their way to the Holy Land. Perhaps there are Christian souls hiding nearby,” said the knight.

“Aye, my lord” responded the archer. “The wells may have been poisoned. We should drink and water our horses only at the springs from now on.”

Days later, when they found another village, it, too, was abandoned and all of the food was burned. They wondered why they had not yet seen a single refugee. What they did encountered helter-skelter on the road between the abandoned settlements were large mounds of dirt. Sir Robert, frustrated by the sight, finally decided to poke at the dirt, and a human hand was revealed. He galloped to another nearby mound and found another corpse interred standing up.

“What foulness,” said the knight.

“Aye, my lord,” said the archer. “It must be a pagan custom.”

They rode on for several more days, barely speaking. But each silently waited for the world that they knew to re-emerge, for human souls to reappear. Even the sight of the enemy would have been preferable to this solitude. Then an unexpected sight appeared. The sun hung low in the sky, and a grove of trees appeared in the horizon, almost as if it could only be seen in the light of the dying sun. The knight raised his arm, and the archer halted at his side. Sir Robert took out his map, a gift from his uncle who had fought in the previous crusade.

“The grove is not marked on the map, Asturias. But the trees look mature. A strange omission, indeed.”

The archer said nothing.

“Could we have taken the wrong path somehow?” said Sir Robert. Then speaking more to himself: “Perhaps my uncle thought it unimportant to mark the grove being that the Monastery of Saint – is but a league from here.”

“Or perhaps…” the archer finally spoke up.

“What?” the knight said irritably.

“My lord, it could be an enchantment of the Devil or some pagan demon. We should ride on.”

The knight ignored the warning and defiantly spurred his horse towards the grove. He was a soldier of Christ, and if he had to battle the Devil himself, he would do so for God and glory.

From the perimeter of the grove, the crusaders could see thin rays of light break through the canopy of the thick ancient trees. A mud brick structure was partially hidden in the shadows.

“Asturias,” said the knight. “Look beyond. There appears to be a house in the grove. There may be someone there.”

Before Eusebius could respond, Sir Robert brusquely spurred his horse forward, but the animal resisted, reared and threw him to the ground. The archer swiftly dismounted and tended to the knight who was stunned by the fall.

“Do not move, my lord. Rest here for a while. I shall investigate.” Eusebius drew his archer’s sword and walked towards the house. The archer found several fresh burial mounds marked by crude crosses of branches tied with rope. The dead appeared to be hastily buried and the odor of decomposition—and something else that was like the perfume of decaying flowers–seeped from the soil. The archer thought, “Perhaps the infidels had recently rampaged through these lands. Or perhaps there had been a plague. Perhaps that is why the villages were abandoned.”

The mud brick house in the grove was partially collapsed and exposed. Eusebius could see barrels and tools strewn about. As he approached, he saw a door which proved to be unlocked and opened with slight push to a second room which had a small cot, a table and stool, and a fireplace for cooking. A kettle hung in the fireplace. An iron pan was hung next to the fireplace, and on a shelf nailed to the wall he found flour, dried meat, and oil, as though someone had recently been living there. He wondered if the owner were nearby.

Eusebius returned and reported his findings–and his suspicions–to the knight.

“I do not trust this place, my lord. It is almost as if it has been set up to lure us in. We should move on, sir.”

The knight, however, aching from the fall, ignored the archer’s words.

“We stay here tonight. The monastery is a day’s ride from here.”

The archer slept on the floor next to the fire not so much to warm himself because it was not cold. It was as if he needed the proximity of that primal weapon, fire. Though he suppressed the thought, he sensed an unseen enemy nearby, and placed a lit torch at the entrance of the room for extra protection. The horses sensed danger, too, because they rustled about nervously. Eusebius took the torch and went outside to calm them. He was suddenly overtaken by a magnetic urge, a perverse curiosity, to return to the nearby burials. His instincts told him there was something there. He went and got a shovel and began to dig up one of the graves. The body appeared to lay in an uneasy repose, as though, she–it was a woman—had been carelessly and unceremoniously dropped. He got on his knees to get a better look, and as he passed the torch over her body, he saw that her torso was exposed, ripped open and desecrated by some unspeakable violence.

“God be merciful,” he said, crossing himself, and filled the dirt back into the grave. As he walked back to the house, he thought he saw the outline of a man standing in the night shadows, but when he called out, no one answered. He gave it no further thought and went back inside to sleep.

Many hours later, Eusebius shuddered, awakened by the horses’ cries of terror. He ran outside and saw their penumbras disappear into the shadows. The archer ran after them, unarmed and without alerting his companion and without the torch. He followed the sounds of their pounding hooves and occasional neighs. Thick clouds moved back and forth, obscuring the moonlight and then suddenly moving again, brightly illuminating the landscape before him. He spotted the horses in a meadow, huddled, whimpering, and rubbing their heads and necks against one another.

When he reached the horses, the clouds shifted once more and the moon shone on what appeared to be a mound. It was not a dirt mound like those they had seen before but a stone beehive mound. In the moonlight, Eusebius saw a narrow opening. “What a strange and ungodly land this is,” he thought, crossing himself. The clouds once again shrouded the moon just as a man emerged from the aperture.

“Greetings!” said the archer. “Are you a Christian, good sir?”

The man said nothing. Eusebius could not make out the other’s face. Then the clouds drifted again and the moonlight shone on the stranger’s face, albeit ever so briefly. The archer squinted his eyes in disbelief, for the fleeting image seemed an abomination. The man’s face appeared to be that of two men squeezed together. The man made a muffled sound, filling the archer with terror. Eusebius ran towards the horses, who had not moved and merely watched him all along as though they were held there by a spell. He mounted his horse bareback and galloped away with the knight’s horse running along his side. Thoughts raced through Eusebius’s mind. Had the animals been lured there by that obscene and ungodly monster? “I must tell my master!”

Sir Robert was disinterested. “We must hurry to the monastery. Our greater mission awaits us.”

When they arrived at the monastery, the gates were wide open. The streets were empty. Nary a human soul was to be seen. Rats scurried about trash and partially burned food. Even the dogs and cats had apparently fled with the people.

“Ho, there!” cried the archer, his voice dissolving into the wind that swept through the main thoroughfare.

“Fear not!” shouted the knight. “We are soldiers of Christ!”

“My lord,” said the archer. “Perhaps the monks are barricaded in the church.”

But the church, too, was empty, undisturbed, as if all had fled in an instance.

“Asturias, there is a foul evil in this land,” said the knight, crossing himself.

“I feel it, too, my lord,” said the archer.

“Let us rest here tonight, and tomorrow we will continue our journey to Syria.”

Desperate, the archer went back to the apothecary’s lab and frantically leafed through books, hoping beyond hope that the pictures would tell him something. The pictures resembled those he had briefly seen before in other books: Soldiers, monks, scenes of battles. In some scenes the holy men confronted God’s spiritual enemies: Satan, demons, heretics, and witches. He ran his fingers over the words, silent as rocks, their secrets locked from him. He was certain that the words in the books, like the powders and herbs in the jars, held the cure to his companion’s ailment.

Exhausted he went to bed, and, as he slept and dreamt, his mind’s eye again saw the images in the books and discerned a pattern that had escaped him before. He got out of bed and returned to the apothecary’s lab. In the flickering candlelight, he studied the pictures and found images half-hidden on the peripheries of the illustrations, faces camouflaged among the shrubs and trees.

In a different illustration, men-like creatures—part bird, part serpent–were embedded in the face of a cliff. They appeared to struggle to free themselves. He turned the page and studied the next illustration. In the foreground, the soldiers of Christ and monks marched in a procession, their feet floating above the ground like ghosts, while barely visible in the background, a mound with protruding hands and feet. Some of the soldiers were kneeling and praying, their eyes heavenward, mouths agape.

Eusebius took another one of the books he had previously inspected: One depicting battles, a castle, and an army of crusaders attacking the castle. One particular scene depicted a pitched battle. The occupants of the castle hurled rocks, arrows, and poured cauldrons of boiling oil at the crusaders. When he saw this illustration the day before, Eusebius assumed that the enemy were the Turks. But something caused him to pause before he turned the page. A curved glass lay on the desk. He had seen the monks use them before to magnify words and objects. He took the glass and held it over the men atop the castle and he fell back with a muted shriek. They were not Turks! They were not even men but the same bird-serpent men-like creatures of the previous picture. “Not even the pawns of the Devil!” he thought. “Something more sacrilegious, things beyond God’s creation.”

Then the sunlight shone on the pages. He had spent the entire night studying the books. He hurried to his companion’s side. The knight was gone.

With Sir Robert’s horse tethered to his, he pressed forward. The road before him wound and ascended towards the mountain. The clouds parted every so often and the sunlight seemed to reveal a different world, strong and godly, as if to press him onward. Then the clouds once again darkened the skies. He caught something out of the corner of his eye, an image from a recurring dream which had haunted him since childhood: An enormous, half-decaying tree twisted with age, protruding from a pile of enormous rocks. He remembered it now. In his dream, there was a hollowed-out space in the trunk of the tree. A crystal would rise from the crevice and float in the air.

He searched many years in his youth for the meaning to the dream, questioning the Spanish monks in the monasteries they had liberated from the Muslims. No one had an answer but a monk who had made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land decades before. The monk said that the Egyptian wizards from the time of Moses had made such a crystal to preserve the bodies of the dead. But Eusebius now wondered: What if the monk was wrong and the crystal could turn lead into gold as the alchemists said? What if his dream had been an omen? For that brief moment, Eusebius’s being was filled with joy. He dismounted and searched the tree for any hollowed-out spaces but there were none. He looked at the pile of rocks. Some of the rocks were not strewn about willy-nilly but arranged in a pattern.

Eusebius sensed that the crystal was hidden there and began to toss aside the rocks. A rune stone became visible. He paid no attention to the rune stone’s images let alone try to decipher their message—their warning. He lifted a slab and discovered a corpse with a gauze-like veil on his face and his body covered with a half-rotted, blood stained shroud. The stench of decaying flowers permeated from the grave. Perhaps the gem was hidden therein. He looked around and found a branch and slightly lifted the shroud and saw that that the corpse’s chest had been crudely slit open. Then the corpse shuddered. Eusebius jumped back and crossed himself. “Did I imagine it, dear God?” he said out loud. But when looked again, he saw the fingers on the exposed hand moving slightly. He threw the slab on top of the corpse and piled the rocks atop the grave and fled at full gallop.

Eusebius felt himself falling and shuddered. He had fallen asleep on the road while riding. He looked behind him, and Sir Robert’s steed walked calmly with that serenity that comes from the lack of dreams, that cursed portal into the unseen worlds. Eusebius wondered if he had indeed seen the animated corpse or if he had dreamt it. Before he could give that further thought, he saw the castle was about half a league away. From there, he could discern the castle’s bluish hue, as if the stones were illuminated by some unseen moon. It would be nightfall soon, so he backtracked to a nearby creek to make camp. The horses grazed for a while, but they returned to the camp when the sun had almost sunk beneath the horizon. They hovered near Eusebius as he cooked a rabbit he had hunted earlier in the day. They lay near him like dogs, as though they took comfort in the fire and his presence. He could have sworn they sighed.

“You are good beasts,” he said rubbing their heads, and he did not bother to tether them for the night.

Later that evening, the waning moon floated over the castle. He saw the dense penumbras of men moving about the ramparts of the castle. He was now certain that they must have kidnapped Sir Robert for ransom as was the custom. He kneeled and prayed out loud to God to steel himself for the uncertainty that lay before him.

When the sky turned to the gray hues of early morning, he saddled the horses, and rubbed their necks. “Wait for me here, my friends, my angels. I shall return shortly with our master.” He fashioned a torch, strapped on his sword, and slung the bow and arrows over his shoulder, and walked towards the castle.

The gate of the castle was swung wide open, as if they—whoever they were–had left it open just for him. From a distance, he could see the courtyard was empty and the only sound was that of the wind. Eusebius knew this could be a trap, but he had to try and find Sir Robert. He walked about the perimeter of the castle to search for a way in and found a collapsed portion of the outer wall. Once inside the wall he made his way inside the castle. In the interior of the castle, he saw objects embedded in the stones. Bright and illuminating, some resembled the contraptions of alchemists and astronomers. Others appeared like toys, not the toys he’d seen, but what a people from another world would conceive of as toys. Others were shards of metal.

When he entered a different hall, the rafters were collapsed as if a projectile had landed there during a battle. The debris of the roof was strewn about, and the sun shone on the walls revealing carved reliefs depicting a story of some kind. Bird and serpent men-like creatures were eating the hearts and entrails of humans and horses. He dropped on his knees and prayed to God for protection for whatever place this was it was not that of the Muslims who at the very least worshiped a God similar to his, if not the very same one. He took the flint stone that hung from his neck and lit the torch. Whatever abominations inhabited this cursed castle could not be immune from fire, that sacred secret stolen by a strange god as a gift to mankind long before his God had existed.

He walked through the spacious corridors, noting distinguishing markers so he could find his way out quickly if need be. Finally, he came to an entrance that opened up to a great hall. A blue-tinged light streamed from the stained-glass windows high above, giving the sensation of being submerged under water. Eusebius saw men–Christian men—standing in the room. He knew that because of the red crosses emblazoned on their white capes. He wanted to call out, but an instinct that had persevered since the time humans were but ape-men abominations themselves silenced him.

Eusebius approached the center of the great hall. The crusaders stood like stone statues around a body that lay in an open sarcophagus. As he approached them, the smoke from the torch could no longer mask the perfume of decaying flowers. The men were mummified. A cobweb-like gauze covered their well-preserved faces, their eyes shut, as if in a strange burial custom. “Like the mounds!” he heard himself say out loud. Eusebius covered his nose with his hand and approached the sarcophagus. He let out a scream. It was Sir Robert! Before he could ponder how or why his master was killed and placed there, he felt the air move.

Eusebius turned around and saw that one of the mummies was moving ever so slightly, like a half-dead insect in a cocoon. Then another opened his eyes and began to move his fingers, just like the corpse he had found by the twisted tree, then another shuddering as if he had awoken. Terrified, Eusebius fell backwards, dropping the torch, and heard a scream. It was not his voice, but Sir Robert’s. “He’s alive!” he thought. Eusebius ran to the sarcophagus to save his companion. The knight struggled to let out one word: “Burn!”

Then he heard thumping of weighted footsteps approaching the great hall. Eusebius knew they were not Christians nor Muslims but them–the ones he had seen atop the castle the night before. They had found him. “Forgive me, my lord!” he said and crossed himself and set Sir Robert on fire. Then he lit the capes of the other crusaders. The great hall was filled with screams as the fire engulfed them. They were still alive, all of them. Eusebius then heard a dull muffled sound approaching one of the entrances of the great hall. The sound was like the attempted shouts of mouthless men. Eusebius ran in the opposite direction, hastily setting fire on what he could. When he reached the courtyard, he spilled an oil barrel in front of the gate and lit it on fire and fled. He looked back and saw the creatures, scurrying about trying to put out the fire before it spread. He could not see them well enough to discern their faces but feathers sprouted from their necks and shoulders, and they moved clumsily as if they were made of stone. He ran down the road and heard explosions as the fire must have surely spread to the nearby oil barrels.

The sun was now beginning to set. From the foot of the mountain, Eusebius could see the castle roof ablaze. The windows were bright orange and reds. Soon, the remaining rafters would collapse and burn everyone inside.

The horses were not far from where he had left them, calmly grazing in a nearby meadow. When they saw the archer, they trotted towards him and huddled close to him as if to comfort him from the grief and despair. Remounting, he rode away and a darkness set upon him, his body slackened, and his thoughts vanished.

“We found you on the bank of the river two days ago,” said the attendant monk. “The horses were wandering in our courtyard. The angels must have sent them to tell us of your whereabouts. You are very fortunate that we have found you. Another day in the cold may have killed you, or you would have caught the plague.”

“Not plague,” Eusebius struggled to say. “Creatures. Vile, ungodly…”

Another monk came into view, the abbot. “No, my son. The plague. It was carried here by two lone crusaders.”

A Story of the Fourth Crusade

“No! Men-like creatures…they poisoned the food. Trapped people in cocoons…ate their hearts and entrails.”

The two monks looked at each, and finally the abbot asked, “Was it a demon?

“Not a demon! Men! I saw them. But I have burned them!”

“He must be delirious, Father,” said Brother James as the archer slipped back into unconsciousness.

“Let him rest,” said the abbot. “We will interrogate him when he recovers.”

“It’s them!” shouted Eusebius. “They live! I must kill them!”

He burst out of the refractory, into the stable, and rode out bareback on the knight’s steed armed with only his sword. The monks were unable to stop him but quickly assembled their entourage and followed suit. The very next night they came within sight of the Monastery of St. ______, where Sir Robert and Eusebius had rested. The buildings were in flames. Just outside of the gates they found the body of Eusebius and what appeared to be another man. Eusebius and his antagonist had apparently killed each other in hand to hand combat. When Brother James turned over the body of the other man, he let out a shriek because it was not a man but a human-like abomination like the one the archer had described.

The monks took the body of the creature and sent it to Rome where it was hidden in the secret vaults of the Vatican.

La Procesión de Sangre de Cristo

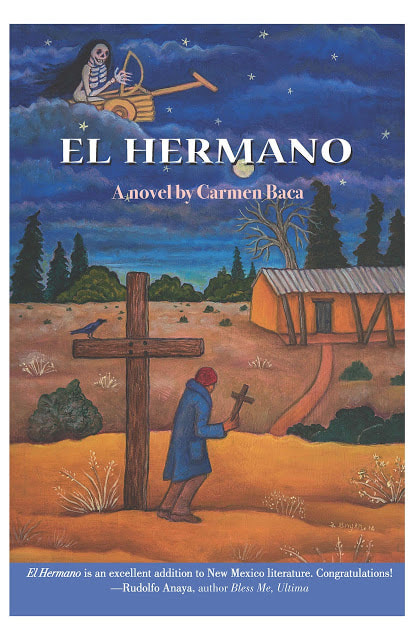

Excerpt from El Hermano, a novel by Carmen Baca

With a review by Scott Duncan-Fernandez

That my abuela was here was no accident, no inexplicable coincidence to agitate my imaginings. For she knew that I had become a novicio the night before, and as médica, she had come to see how I fared. She moved to my side with a jar of her remedio, turned me to my side to rub the romerillo, or silver sage, on my back, and then tucked the quilts around me once again without a word.

My mother placed a mug of warm broth in my hands, brushing a gentle hand over my cheek and pulling a chair by my bed for my gramma before she left for the church with my aunt. A few of the women would give the capilla a light cleaning before covering the saints with cloaks of black this morning to symbolize the dark day of Christ’s death. They would remain concealed until Easter morning, the day of His resurrection.

Settling herself comfortably, gramma took from her apron pocket a small kerchief with a trailing thread and proceeded to continue her embroidery on its edge, the needle whipping in and out of the intricate design with a delicate, almost birdlike fluttering of her hands. I sipped the warm soup watching her, waiting for her to speak. I knew I had inherited my physical appearance from her, the small, thin stature, the nose, and her humor. Had I also inherited a mental power I didn’t understand, or want, from my beloved grandmother?

Before I could ponder the question further, before I could think of a way to phrase my question without hurting the feelings of the tiny woman seated beside me, she spoke.

“You have a gift.”

Her words revived my concerns that the warm broth had begun to dispel.

She looked up from her embroidery. Although this was one time I wished I could turn away, I forced myself to look into her eyes. Bright with tears, hers held a mixture of sadness and regret. When she blinked the drops away and smiled softly at me, there was also pleasure and expectation in their depths.

“The gift of sight,” she began, “is strong in our family though inherited by some, not all, through the generations. And,” she added, “while some seemed only to possess a strong sense of intuition, there were others who had the power to know other’s thoughts, especially of people with whom they were close.

“I will tell you a story, hijo, a cuento of a young girl you know well.” Putting her embroidery aside, she settled back into the pillow at her back and continued.

“When this girl was very young, she began to have disturbing dreams, dreams which frightened her because in the days that followed, they would almost always come true. More and more often as she grew, the dreams plagued her. And her abuelito, the only one who believed her, died before he could explain the gift she had inherited from him. She learned to keep the dreams secret because whenever she told anyone, they looked at her as if she were loca. And people, ignorant and afraid, had started to think she was either crazy or a witch.

Years passed, until one night she saw her father in her dream and knew what real fear was. In her vision her father was being dragged by horses in the field he was plowing, his leg entangled in the reins behind the arado.”

She paused, taking her sack of punche from her pocket to roll a cigarette.

I squirmed restlessly on the bed. From past experience, I knew that it was an effort in futility to urge her on, for if prodded to finish a cuento before she decided she wanted to, she was known to teach me a longer lesson in patience, sometimes making me wait for days, or until I had even forgotten the beginnings of a story and her teasing reminder would set me off, begging for the end.

I had to hand it to my abuelita; she knew how to build up the suspense in her stories like no one else. I was forced to wait as she took a laboriously long time rolling her smoke, her eyes twinkling with mirth at my discomfort.

“Where was I?” she asked, striking a wooden match on the sole of her shoe.

“Oh, yes, the dream.” Puffing a small stream of smoke, she continued, “The next morning, much to her dismay, the girl’s father had already begun to plow the fields when she awoke. Without breakfast, the girl ran out of the house, straight to the field.”

When she paused to puff her cigarette again, I could have screamed from the suspense; it was killing me. “Now, the neighbors had honey bees,” she reminisced, “and the hives were just across the river. For some reason, I never knew why, they swarmed—and the girl’s father with his horses were right in their path. It was a good thing the girl got there when she did, for her father, strong though he was, was already struggling to keep the horses from running away with the plow. When she looked down, the girl saw that the end of one of the reins had tangled around her father’s leg, just like in her dream. And just as the panicked horses took off, shaking the bees from their heads, she jumped forward, unwrapping the rein just in the nick of time to save her father from a very bad injury—perhaps even death.”

Gramma puffed at her cigarette a moment before she added, “That was the day the girl finally realized that her dreams were not the curse she had thought they were all along, for years having been afraid that perhaps she was a witch and that she had dark powers from the devil. They were forewarnings, a gift from God, and she had learned to read their meaning to help others.”

Putting her cigarette out, she looked at me closely, searching my eyes for understanding. “Sí,” she said quietly, “I have been called bruja many times, hijo, but only by the ignorant or the envious, God help them. They do not know that what I have is a gift from God and that I have learned to use my gift to avisar or to give consejo to those I see in my dreams.”

I breathed a sigh of relief, knowing that no matter what happened in the future, I would never suspect my abuelita of being a witch again. And I understood that my father possessed a different gift, a power to read my thoughts and to respond in the voice of my conscience to guide me in the journey of life. But at the same time, I was troubled. Hadn’t I also inherited such a gift, a power to see or hear things others didn’t?

I knew she picked up the apprehension in my eyes, for my gramma said softly, “No te preocupes. Do not be worried, hijo mío. Instead, thank the Lord that you have something not many people do and learn to use your gift to help yourself and to help others if you’re able. And if your friends question your intuition, you do what your conciencia tells you. If they are real amigos, they will look to you for consejo. Advise them well. If they are not, then you will have to live with their suspicions and their accusations just as I have. And though it will be hard, you will have to learn to leave them to their own consciences.”

I nodded, and we sat in companionable silence for a while. My gramma took up her embroidery again as my mind digested the importance of her story, her counsel. I knew that I would have to find within myself the strength to overcome my disquiet, to listen and watch for any avisos in the future, to use my gift of intuition wisely.

Suddenly remembering what I had seen the night before, I asked, “Do you believe there really are witches?”

“¿Por qué?” she asked, looking at me quizzically.

I described our encounter with the ball of fire and what Berto had done as it had fled.

She nodded, “There are many, including myself, who have seen them. And since there is no explanation for the balls of fire, there are many who believe that they are witches. No one knows for sure. But it has been a long time that any have been seen around here.”

“What do you believe?” I asked, a little uneasy about her answer.

“I believe that there is a power of good, which is God. But the Bible tells us that there is also a power of evil. Just as Dios gives His children gifts which help them to live as good Cristianos, then so could el Diablo guide those he chooses with the powers of darkness.”

She crossed herself before she looked at me for a moment. “That you saw one during la Cuaresma disturbs me. This is one of the most sacred seasons of the year. If it was a bruja or some other work of el Diablo, then they seem to have no fear that this is Lent, and today is Viernes Santo, the day our Savior died.”

“What could it mean?” I whispered.

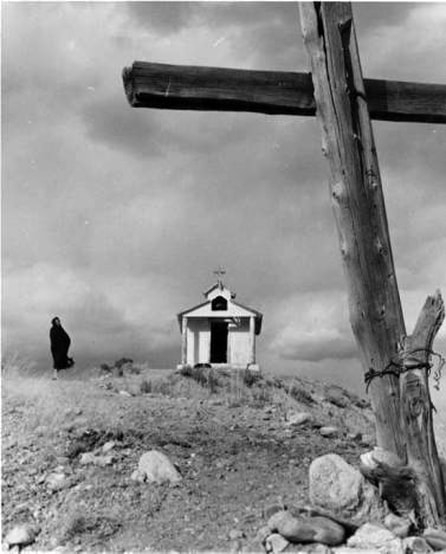

The heavy silence of our thoughts spoke volumes, for we both knew that this afternoon La Procesión de Sangre de Cristo, the procession of the Blood of Christ, in which a chosen Hermano would carry the crucifix from the morada on his back, would be enacted. And even though the Penitente would not be crucified, the re-enactment of the most sorrowful day in the life of our Savior would take its toll on the Brother who played the crucial role. I wondered if it would be the Hermano who had portrayed Christ the night before in la Procesión de la Santa Cruz.

la bandera; Miguel's house in the background.

“What do you think happened to her?” my mother asked, looking from my grandmother to me and back at her again.

My abuela’s face mirrored my thoughts: a bruja! Could the one who had protested the most loudly that she was surrounded by witches and lunatics in fact be a witch herself? Could Berto’s rock have met its mark on the floating ball of fire, leaving in its stead a wound in a witch that would cause her death?

I knew that neither my abuela nor I wished the woman harm, yet I saw in her eyes the question I felt in my heart. If the woman died, then would the significance of the ball of fire we suspected be dispelled by her own death?

Unable to rest and unable to sleep, I rose when Berto appeared at my door about noon, sent to see if I was well enough to go to the morada before the procession began. At first my mother protested, having heard of my induction from my father earlier that morning. But rising unsteadily, I assured her that I felt better and that if los Hermanos had sent for me, surely I was needed at the morada. Physically, it was the truth, for my chills had subsided and I was no longer dizzy, but my mind whirled with questions and an impending sense of doom.

Concerned about how Berto would react if he heard of what had happened to the Lunática from someone else, I broke the news to him gently. Though I tried to convince him that we didn’t know whether the woman was only an innocent recluse who had fallen, perhaps even attacked by a thief (which was unheard of in our community), I heard the doubt in my own voice and saw the disbelief in his eyes. Berto remained convinced that the woman was a witch and that she had been injured by his hand, the hand which had cast the stone.

He ran his fingers through his shock of hair again and again, upset about her probable revenge. I, too, worried for Filiberto, remembering my grandmother’s words.

When we arrived at the morada, the Hermanos were resting beneath the shady cottonwoods outside. I went from one to the other exchanging greetings, touched by their concern. My father beckoned to me, moving a little away from the others so we could speak in private. He asked if I was up to the long hours ahead.

After I assured him I felt fine, he told me what had been decided during the morning in my absence.

When he told me who would be the Cristo in the procession of the afternoon, I frowned. My Tío Daniel who had been chosen for the honored role the night before had asked for and received permission to again portray Christ in the reenactment of His walk to Monte Calvario. I needed to tell my father about the premonition of impending death I sensed, but there was no way to explain without beginning with the ball of fire the boys and I had encountered the night before. So I took a deep breath, plunged in, watching his eyes widen when I told him what Abuela and I had discussed, and finished with the account of the neighbor woman’s mysterious injury. I breathlessly waited for his reaction.

He took it all in, quiet with thought before he spoke. “I am glad that your abuela explained about what it is to be a gifted member of this familia,” he said, “for from now on you will listen more closely to your intuition to guide you on the right path in life.”

“But that’s just it,” I blurted, “I have a queer feeling about what gramma said about someone dying. As much as I don’t like that lady for how she treated gramma, I don’t wish her dead, but if she does die, at least that might mean Tío Daniel won’t.”

“Perhaps Mamá is right,” he said. “I trust her judgment,” he added, laying a hand on my shoulder, “as I also trust yours.”

He stood, and I felt a surge of pride that he spoke to me as one man to another.

I waited for him to say that the procession to follow would be canceled or that he would put it to a vote of all the Hermanos, but when he spoke I knew that it wasn’t something he had the power to do. The rites and rituals of the Penitente Brotherhood were clear, and the reenactment I dreaded would proceed as usual.

“We will do what we must,” he said with determination, “and we will pray that Daniel will not be the one who has to die with Cristo tonight.”

We walked together back into the morada where the rest of los Hermanos were in prayer. The window, covered with a dark cloth, let no welcome warmth or light into the room. In the chill of the thick adobe walls there were only the flickering flames of candles to shed a wavering glow on the altar and the men kneeling before it. As we joined them, I took the crucifix I had finished carving, painted black the day before, and placed it among those of my Brothers and the small covered santo Pedro had carved.

Kneeling, I waited for the peace I always felt when I prayed there. I longed for the solace I would have received if I were able to look into the face of the Savior. But every retablo, every santo, was covered in shrouds of black. I felt a sense of loss, of foreboding—until I closed my eyes. From the dark recesses of my mind the face of Christ emerged, filling me with strength to face whatever might occur.

It was a little before two o’clock when we emerged from the morada, blinking our eyes in the welcome light of the sun, warming our stiff bodies in its rays as we were surrounded by the friends and relatives who had come to join our procession. Women bustled into the cocina with pots of food while others entered the prayer room for a moment of contemplation before we began.

I greeted my mother and grandmother with a hug, reluctant to let either of them go, for in their arms I felt the comforting reassurance of my youth. I found myself close to tears, realizing that the innocence of my childhood was lost to me, only to be remembered in their embrace with the bittersweet knowledge that I had willingly forsaken the child within me and let the man in me emerge when I took the vows of a novicio.

Collecting myself as best I could with the tumultuous emotions and frightening premonition looming over my thoughts, I made my way over to the boys who were resting beneath the trees, knowing if anyone could take my mind off my worries, it would be the gang. Horacio was speaking as I joined them.

“My gramma told me a cuento once,” he said quietly. “She thinks it’s only a legend though, ’cause she never really heard of it happening in her lifetime.

Her own abuela told it to her when she was a girl. Do you wanna hear?”

Berto nodded. “Anything, if it’ll stop me from thinking about the bruja.”

We all looked at Berto sympathetically, wishing we could relieve him of the burden of his fears and knowing there was nothing we could do except keep his mind off them.

Horacio began, “Well, you know how Tío Daniel is going to play the Cristo and carry the cross on his shoulders in a while?”

“Don’t remind me,” I waved a hand at Horacio to continue when the boys’ confused looks turned on me. I was thinking of my uncle’s nightmares about the war and wondering if this was his penance for some unimaginable act.

“Anyway,” Horacio continued after looking at me askance, “my gramma told me that one of the descansos up there,” he pointed his chin to the mountains beyond the church, “is supposed to be a real grave, the grave of an Hermano who died while he was acting the part of Christ.”

We gasped. Pedro added, much to my discomfort, “It could be true, you know. I heard my papá and my grampo talking once, and they said that in the old days the one who played Cristo was really crucified on Viernes Santo, only instead of nails, they used ropes to tie him to the cross.”

I was unable to shake off the chills that rose up my spine. Though I noticed the others squirming as well, I knew my distress for my uncle was greater than theirs because they had no knowledge of my conversation with my grandmother.

“All I know is what gramma told me,” Horacio finished, leaning toward us. “She said that if it was true, then the Hermano who died would go straight to heaven. In those days, no one was allowed to witness the procession, but what was stranger was that the dead man’s shoes were left on his doorstep so that the family would know how he had died, and for a whole year no one but the Penitentes knew where they had buried him.”

We all took this bit of news in silence. I pictured the scene Horacio described and thanked the Lord silently that we didn’t do things the old way anymore, and then Pedro spoke up as if reading my mind.

“I’m glad we don’t do it that way anymore.”

We all agreed. However, as we rose to join the men already getting into formation, I saw the black crucifix carried on the shoulders of two Hermanos who emerged from the morada. The moment for which I had longed for so many years—and only today had come to dread—arrived. For the first time, I would take part in the procession of Penitentes, but the pride I felt was overshadowed by the knowledge that my uncle, whom I loved like an older brother, would be in the lead carrying the heavy cross. I knew my eyes would be upon him all the way. Coupled with my foreboding that someone would be dead before morning, my first procession became a penitence indeed.

I sighed heavily, lining up with Pedro at the rear of the group. As everyone who gathered to join the procesión took their places behind us, I was surprised to see Primo Victoriano, leaning heavily on his bordón, directly behind me with his wife, Prima Juanita. I noticed Berto and the others positioned behind him, ready in case he needed assistance.

I turned and offered the elderly man my hand. “If you get tired, everyone will understand if you have to stop,” I told him in a whisper.

“I will,” he promised. “I just had to come one last time, you understand?”

The longing in his withered face was enough to tell me that this might be the last Lent he would see in his lifetime, that this might be the last chance he had to join his Brothers before age or ill health took its toll.

I nodded in understanding, but I saw the weariness of his eyes, in the way he leaned on his cane, in the way his breath emerged from his mouth in short, tired gasps. “Don’t overtire yourself, primo,” I warned, but he only waved my concern away with a hand.

The procession began when my father’s voice rose to announce that this was the reenactment of the Passion of Christ. My Tío Daniel, the massive black cross on his shoulders, moved forward, setting the pace for us to follow.

“Oh—ohhh, imagen de Jesús doloroso para ejercitarse en el santo sacrificio de la misa como memoria que es de tan sacrosanta pasión,” my father intoned, telling us to imagine our dolorous Savior fulfilling His destiny in such a sacred sacrifice in our reenactment of the memory of such a sacrosanct passion.

I read along as the rest of the Hermanos joined in, my voice blending with the varied pitches of the men, rising and falling with each line. The music emerged as if from our very souls to waver and float around us as we spoke to our Savior in a somber hymn rather than with mere words. The very tone of our combined voices and the reverence with which we sang spoke volumes as our words conveyed how much we believed in the passion of our Savior.

My father’s words conveyed that Jesus had revealed many times to his faithful servants what was to follow. And though no one actually did the things to my uncle that my father told us, he paused with each recitation, and the weight of the words he spoke with such tremulous emotion made us feel that just by describing the terrible things done to Christ he felt them in his heart as he carried the symbolic cross.

Then the first time he stopped, Tío Daniel spoke loud enough for all to hear the words that indeed seemed to be the words of our Savior: “Primeramente me levantaron del suelo por la cuerda y por los cabellos viente y tres veses.” My uncle revealed, “First they lifted me from the floor by rope and from my hair twentythree times.”

As he resumed the pace for the procession to follow, my uncle paused twenty-one more times. His pace slowing with each pause, Daniel fought the trembling of his legs. I saw his shoulders bend under the cumbersome cross, symbolically weighing heavily in our hearts each time he staggered under its massive bulk. Even from where I stood, with twelve men before me, I heard his breath come more heavily, his voice emerged more tremulously, the words quaver as he described the countless terrors suffered by Christ in His passion.

“They gave me six thousand, six hundred, sixty-six lashings of the whip when they tied me to the column …. I fell on the earth seven times … before I fell five times on the road to Mount Calvary …. I lost one thousand twentyfive drops of blood.”

By the time we were halfway to the church, many of the women were sniffling, wiping their eyes with their kerchiefs. But the worst was yet to come as my uncle continued, weakened but undeterred in fulfilling his role.

“They gave me twenty punches to my face …. I had nineteen mortal injuries … they hit me in the chest and the head twenty-eight times …. I had seventy-two major wounds over the rest.”

By this time some of the women were weeping openly, and the smaller children, frightened beyond belief—I knew because I was at their age—began to sob quietly at their mothers’ distress. Primo Victoriano stumbled behind me, and I stepped back to grasp one elbow as Berto took the other. The determination in his face to reach the capilla, to finish the procesión as an Hermano one last time, was heart-wrenching. And as I took some of the weight off his feet with my support, I felt tears gather in my eyes.

“I had a thousand pricks from the crown of thorns on my head because I fell, and they replaced the crown many times,” my uncle’s weakened voice continued.

“I sighed one hundred nine times … they spat on me seventy-three times.”

The tears flowed down my face. I heard Primo Victoriano’s labored breaths at my side. I thanked God the procession had come to an end, for the words were too painful to bear, humbling our Christian souls to the core of our being.

“Those who followed me from the pueblo were two hundred thirty,” my uncle finished, “only three helped me …. I was thrown and dragged through barbs seventy-eight times.”

As we reached the capilla, my uncle was barely moving, his feet shuffling wearily in the dirt, his breathing labored. When he leaned precariously forward, the cross threatening to smash him into the earth, several women cried out in alarm. Leaping quickly to his aid, my father and Primo Esteban each grabbed an end of the beam lying on his shoulders, relieving him of his burden just as his knees buckled beneath him and my uncle fell to the ground on hands and knees.

When I saw him fall, his face grimaced in pain, my heart throbbed in fear that he could be gravely hurt, that my premonition of an impending death would come true. I would have rushed to his side but for Primo Victoriano, whose arm clutched mine tightly, his shoulder leaning heavily against me. If I left him, he too would fall.

All the women were now sobbing as they looked at my uncle, trying in vain to stifle their uncontrollable cries because of the children, who, too young to understand what we did, cried with distress and sympathy for their mothers’ tears. A few of los Hermanos rushed to help my uncle to his feet, supporting him as they took him into the church. Though he was exhausted, my tío appeared to be unhurt, and a collective sigh of relief shivered over us. The women calmed themselves and mothers or older sisters hushed children’s cries into soft whimpers.

Primo Victoriano continued to shake against me, his legs quaking with his effort to remain standing, his breathing heavy. Beginning to falter under his weight, Berto motioned for Pedro to help us, knowing that my scrawny frame wouldn’t be enough help to get the elderly man into the church. Relieving me quickly, they placed our primo’s arms over their shoulders, supporting his weight between them as they moved slowly into the capilla with his wife at their side. Following with Horacio and Tino, I heard Primo Victoriano mumble disappointedly at himself that he had no strength left to light the fire or the candles inside. Exchanging glances and nods, we hurried inside, so that when our Primo reached the door, I was busily feeding the flames of the kindling I had lit in the stove and

Horacio and Tino were moving from candle to candle quickly. Turning as he entered, I smiled, glad that we were able to relieve him in his duty now that he needed us. Primo Victoriano only nodded, but the gratitude in his eyes said it all before he allowed the boys to settle him comfortably in the pew nearest the stove.

When the Estaciones ended that evening, there was a silence unsurpassed by any service we had yet attended. I knew that for those who prayed with los Hermanos it was in part because of the anguish of witnessing la Procesión de Sangre de Cristo and the terrible sorrow of las Tinieblas that was to come back at the morada afterward. For Pedro and me, it was something more. We knelt with los Hermanos as novicios in the center aisle of the capilla as we made our slow and somber revolution of prayers and alabados around the retablos of the Stations of the Cross. I found my place in my faith, and it affected me as nothing before had done. It was awesome to contemplate.

When my father signaled that it was time for our return to the morada, I retrieved my black crucifix from the altar. I blew out a candle with a fervent prayer for my uncle’s health and took another taper with me to the door of the now darkened church. Spotting Primo Victoriano, supported between his wife and Berto’s mother, I went to say good night. Someone had gone for a wagon to take the elderly man home, Prima Cleofes explained, for he felt tired.

Prima Juanita clucked her tongue at her stubborn husband, but he didn’t need to say a word. The soft smile that lit his face told me that he had done what he had set out to do. He was content that he had accompanied his Brothers one last time, and he would toll the bell also for the last time that night before he would allow himself to be taken home.

When I saw los Hermanos taking their places in the center of the road, I bade him good night, telling him to rest and not to worry, I would be there to help him on Easter Sunday as well. In the soft glow of the lanterns and candles, his eyes grew moist.

Blinking back his tears, Primo Victoriano looked at me gravely. He said, “I will be here on Sunday, hermanito, and you will light the candles for me, but I will not see their light. I will not feel the warmth of the fire you will make.”

Confused by his cryptic message, I searched his eyes. From the quiet contentment and resoluteness of his gaze, a silent tear that rolled down his withered cheek and touched my heart. My respect and admiration for the elderly Hermano who had fulfilled his desire engulfed me. On impulse, I hugged him close for the first, and for what would also be the last, time in my life.

near Chimayo, New Mexico

Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA)

Negative number: HP.2007.20.562

El Hermano:

A living link to a way of spiritual survival

El Hermano, a first novel by Carmen Baca, brings to life through the story of a young boy in late 1920s New Mexico, the wonder of Los Penitentes, who have been painted by rumor and misconstrued in fiction as backwards and brutal, as cult rather than a humble brotherhood of Catholic men. El Hermano could have been the story of my own great-grandfather, a Penitente brother who died a few years before I was born and thus I know as little of him as the brotherhood to which he belonged. Both the shed on the family ranch and the chapel he built down the road where perhaps he carried out some brotherhood rites still stand and have been objects for reflection on his life and Los Penitentes for me for many years.