A Cuban Soap Opera Remakeby Matias Travieso-Diaz and Eloy Gonzalez-Argüelles [I want to speak, I want to speak, tell everyone Albertico Limonta is my grandson, the child of my oldest daughter Maria Elena.] Don Rafael del Junco’s silent litany in El Derecho de Nacer by Felix B. Caignet In mid-2047, the Instituto Cubano de Radio y Televisión (Cuban Institute of Radio and Television, or CIRT), received a proposal for a revival of the 1948 radio soap opera El Derecho de Nacer (The Right to be Born) by the Cuban radio writer Félix Benjamín Caignet Salomón. At the time, El Derecho, as it was called, swept Cuba by storm, and then spread to all of Latin America in a run that lasted over fifty years. It was regarded as one of the most influential soap operas of all time, and had been the subject of numerous radio, television and movie adaptations. The revival (in the form of a TV series to be aired in Cubavision) was to start in April 2048 to coincide with the centenary of the original radio broadcast. José (“Pepe”) Cubero, a brilliant movie and TV producer and director, was the proponent and strongest defender of the project. He acknowledged that the 1948 soap opera would have to be modified a bit to make it consistent with the culture and politics of twenty-first century Cuba, but felt the changes would be small and well within his creative abilities. The proposal met opposition from some of the most orthodox members of the Communist Party. They claimed that the original story was rife with the type of bourgeois, capitalistic ideology that had been eradicated after almost ninety years of Socialist rule. Other opponents, more practical, pointed to the chronic economic crisis that bedeviled the island with words like these: “Anything we broadcast must encourage the Cuban people to work harder, make sacrifices, concentrate on rebuilding the economy in the face of the heartless Yankee blockade. El Derecho is a frivolous, escapist diversion that would get us sidetracked from our mission. And it will run for many months, compounding the damage.” The matter was kicked upward to land on the lap of Miguel Diaz-Canel, who had been President and First Secretary of Cuba’s Communist Party for almost thirty years. He was in his mid-eighties and getting ready to step down, so he was in no mood to mediate in ideological disputes. He ruled: “Let Pepe Cubero come up with a proposed screenplay and give it to the President of the CIRT and the Minister of Culture. Let those guys decide what changes to the screenplay are required to render it acceptable, make those changes, and run with it. Don’t bother me with this shit again.” The Minister of Culture, Haydée Alonso, who had studied in Paris, quoted Sartre, and prided herself on being open-minded and liberal (within the ideological bounds of the Party), was enchanted with the idea of a revival of El Derecho, so she was inclined to give Cubero a relatively free hand. This was good news to Cubero, although no one else liked Haydée. No one forgave her for her unpatriotic preference for smelly Gauloise cigarettes that stunk up the studio, and that she did so “in the land where the best tobacco in the world used to be grown.” The CIRT President, Danylo López, was an old, dried-up bureaucrat concerned mainly with toeing the Party line and avoiding controversies, and was not amenable to letting Cubero get away with much. Torn between polar extremes, development of the new version of the soap opera proceeded in painful fits and starts. The first bone of contention was the character of Don Rafael del Junco, the villain of the story. Everyone agreed that Don Rafael, a haughty unscrupulous landowner, was a proper embodiment of the pre-Revolutionary capitalistic class. However, at the end of the original 314 episodes, Don Rafael reconciled with his daughter and grandson, and ended up being presented in a somewhat favorable light. “We have to change the ending” argued Danylo. “There can be no redemption for the enemies of the people.” Cubero reluctantly agreed to modify the end of the series so that Don Rafael got his comeuppance. He was hoping against hope that by the time the last episodes were filmed Danylo would have changed his mind. Then there was María Elena, the daughter of Don Rafael and mother of the hero of the series. Again, everyone agreed that she showed courage in refusing to have a late term abortion and insisting on giving birth to her illegitimate child. However, in the original series she sought shelter for her grief in a convent, where the nuns and other members of the community treated her with compassion and understanding. Danylo was loath to include any episodes that praised religious people. “Religion is the opium of the masses, and the State must not condone it in any manner.” Cubero had to change the script to have María Elena become a sort of hermit, seeking solace from the apparent loss of her child on a deserted shore. That in itself was problematic, since Cuba had implemented an internal passport system that was rigidly enforced. In the new Cuba, there was nowhere to hide. At the end, this discrepancy was allowed as poetic license, hoping it would not be noticed by anyone who had the power to object. In the original El Derecho María Elena leaves her newborn baby boy in the care of her once wet nurse, the black María Dolores, who saves the infant from being slain on orders from Don Rafael, manages to give Don Rafael the false impression that she and the baby are dead, and escapes with the infant to a remote village. There, she raises the boy as her own child, naming him Alberto (“Albertico”) Limonta. One salient and recurring problem was the relationship between “son” and “mother,” due to the fact that María Dolores claimed he was her son, even after his infancy. Yet, the actor chosen by Cubero to play Albertico, Ontario (“Guapito”) Ledesma, was white. Very white. Blondish. On the other hand, the lady portraying María Dolores was black, as stipulated by Caignet in the original soap opera. Coal black. No one seemed to find the discrepancy odd except for Haydée, who said that the role of María Dolores seemed taken out of Gone with the Wind. Her remark was met with a deadpan silence, for nobody in Cuba remembered or cared about old Yankee movies. The racial disparity problem did not fully surface at first, because the boy who played Albertico as a child had a darker complexion that made his relationship with María Dolores more credible. But later on in the show, when Ontario assumed the role of 25-year-old Albertico, María Dolores’ claim that he was her son began ringing hollow. Different suggestions were considered: darkening Ontario’s skin with blackface make-up like Laurence Olivier in Othello, other things of that nature. Haydée opposed them all, because, she said, it was not impossible that Albertico could still be María Dolores’ biological son. So, things were left unchanged. There was one scene, however, when the script called for older Albertico to run up to his mother and say, “Mamá, I love you so” as he hugged the black woman. The scene had to be redone many times because the crew in the studio—and later on, even Albertico and María Dolores—could not control their laughter. In the end, the scene was filmed as it was and prompted sarcastic comments among the viewers once aired. Much was done in the original series to highlight the discrimination and ill treatment that both María Dolores and Albertico endured on account of her race. Danylo liked that and wanted to accentuate the criticism of the racist society that existed in the country before the Revolution, but was opposed by Haydée, who warned not to overdo that aspect of the plot. “Remember, Danylo,” she said, “there are still people left in this country who believe blacks are inferior, although they won’t openly admit to it. There is no point in rubbing their noses on our commitment to equality among the races.” At the end, Danylo carried the day. Albertico, who was white, would be repeatedly abused and discriminated against for having a black mother and being a mulatto. In one scene intended to bring more “realism” to the story, a classmate of Albertico has a fight with him and calls him an “hijo de puta” (a bastard), not an uncommon insult in Spanish. Danylo objected to the use of such foul language, as it was not in keeping with Socialist morality. Haydée replied that this choice of words was used by ordinary people and prude sentiments to the contrary were a bourgeois atavism. A heated debate ensued and, at the end, Haydée seemed to say that the language in the series should not be controlled by a “partido de hijos de puta,” which many people took to refer to the Communist Party. Haydée, however, swore that she had not said “Partido” but “partida,” meaning “bunch” or “group,” without any political connotation. Since no one could produce a definitive argument, the matter was dropped, along with the entire scene. Many episodes later, thanks to María Dolores’ innumerable sacrifices, Albertico manages to make it through the university and becomes a famous doctor. In the original version, Albertico gets to be rich and lives in comfort with his aging “mother.” Both Danylo and Haydée objected to this turn of events. Cubero was required to rewrite that part of the story to have Albertico live modestly, see indigent patients for free, and travel to Haiti to help treat the victims of a devastating earthquake. In the rewrite, Albertico returns to Cuba with a newfound social conscience, alert to the inequities of the capitalist society and committed to fighting them. Later in the series, Albertico is doing night duty at a public hospital’s emergency room when several injured people are brought in after a traffic accident. One of them is an old man who is bleeding to death. The victim’s blood type is AB negative, the rarest type, which is unavailable at the ill-equipped public hospitals of pre-Revolutionary times. Albertico, AB negative himself, gives a transfusion that saves the man’s life. The victim, who is no other than Don Rafael del Junco, recovers and as he convalesces, he invites his savior to come to dinner and meet his family. There Albertico meets Isabel Cristina, daughter of María Elena’s sister Matilde, and a budding romance blooms between the couple, unaware that they are cousins. Danylo was not in favor of retaining potential incest as part of the plot, and Cubero had to add another twist at the end of the story where it is revealed that Isabel Cristina is not the natural daughter of Matilde, but only an adopted one, eliminating another potential offense to Socialist morality. Don Rafael, now fully recovered, is one day taking a stroll near an outside market, when he spots an old black woman that he immediately recognizes as María Dolores, who he had written off as dead many years before. He follows the woman, overtakes her, and confronts her. María Dolores acknowledges that she and Albertico are alive and well, and rebukes Don Rafael for his cruelty. Cubero is asked to add language to the confrontation scene wherein María Dolores lists once again all the aristocrat’s misdeeds and concludes with a stirring pronouncement: “Beware, for your days are numbered. The people soon will hold you accountable for all the crimes you have committed against your family and against society.” Staggered by these revelations, Don Rafael returns home, where he promptly suffers a stroke (“derrame cerebral”) (a common mishap in soap operas) and falls into a coma. In the original version, Don Rafael stays in a coma for many months, burning with desire to impart the crucial news of the existence of his missing grandson to his wife and daughter, but is paralyzed and unable to speak. Here, however, science rather than politics interferes with the progress of the story. By 2047, a process had existed for years by which an artificial intelligence (AI) could accurately decode words and sentences from brain activity. Using only a few seconds of brain activity data, the AI can guess what a person is trying to say and translates it into a voice recording. The AI was commonly used throughout the world, including Cuba, to help people unable to communicate their thoughts through speech, typing or gestures. The existence of the AI technology rendered a crucial portion of the original version of El Derecho vulnerable to ridicule by the viewing public. There was no way Don Rafael could linger, speechless, for several months. Cubero and his creative team struggled with the problem for weeks and finally had to come up with a lame solution: Don Rafael suffers a “derrame cerebral,” but recovers almost immediately and, instead of bringing the existence of his grandson to the attention of everyone, has a change of heart and continues to cover up his earlier nefarious crimes by accusing María Dolores of theft and charging Albertico with complicity in the black woman’s schemes. Isabel Cristina, whose love for Albertico has not been diminished by Don Rafael’s accusations, alerts her boyfriend before the police can seize him, and Albertico escapes to a bitter exile in Tampa, where his mulatto identity subjects him to additional discrimination and mistreatment at the hands of the American imperialists. Meanwhile, María Dolores lingers in jail and ultimately dies of sorrow. From that point on, the plot of the revival diverges entirely from the original radio show. Albertico becomes a revolutionary hero and travels back to Cuba to take up arms in the mountains against the corrupt government. He alerts Isabel Cristina of his whereabouts and she joins him to continue, together, their fight for justice. Through one of his comrades, who knew Isabel Cristina’s parents, it is revealed that Isabel Cristina and Albertico are unrelated, whereupon the couple is chastely married in a civil ceremony conducted by a rebel leader. They are enjoying a brief honeymoon when they learn that Don Rafael has been killed in a terrorist attack against the Presidential Palace, where he was attending a reception. Albertico and Isabel Cristina kiss and hug each other, relieved at the evildoer’s death, and the series ends. As the first six episodes were filmed, José Cubero had increasing misgivings about the product he was going to set before the public. Technically, the series was as good as he was capable of putting together: photography, score (instrumental renderings of Cuban ballads going back to the 1800s), sound effects, customs, editing, were all first class. He had assembled a cast of experienced actors and actresses, with a famous Spanish TV personality in the role of Don Rafael. Much of the series was shot in locations selected for their beauty or historic interest. Artistically, though, Cubero felt he was doing a disservice to—actually, betraying—Caignet’s original work and regretted all the compromises he had been forced to make to get the project approved. As a way to hide his guilt, he made sure of the destruction of all copies existing in Cuba of the audio, TV and movie versions of the series, be they from Cuba, Puerto Rico, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Venezuela or Mexico. Cuban censorship saw to it that no written materials describing the 1948 series were available to the public. Since there was nobody alive who had listened to the original broadcast, Cubero felt confident that he would not be confronted by critics of the savaging he had been forced to perform on the original. Still, he went to bed the night of Tuesday, March 31, 2048 with a heavy heart, in anticipation of the premiere of the series the following evening. He tossed and turned in bed all night and, in the few minutes of actual sleep, was accosted by the image of a dapper slim man sporting a trim moustache and a mane of black pomaded hair, who appeared and disappeared before him making menacing gestures and repeating incessantly a single word: “Why!!?” The first episode of the new rendering of El Derecho de Nacer was shown on Cubavision at 9 p.m. on April 1, 2048. The show ran, Monday through Saturday, for 310 episodes, the last one playing in the spring of 2049. While initially garnering much public attention, interest in the series wore off quickly, so that the last episodes were seen by almost nobody. Many concluded that much of what was shown and said in the series was predictable and no different, except for its excessive duration, from other political indoctrination efforts by the government. José Cubero finished producing the last package of ten episodes and sought and was granted permission to take a short vacation abroad to recover from his massive effort. He was last spotted taking an Iberia plane bound for Madrid on April 15, 2049. He was never seen again.  Matias Travieso-Diaz was born in Cuba and migrated to the United States as a young man. He became an engineer and lawyer and practiced for nearly fifty years. He retired and turned his attention to creative writing. Seventy of his stories have been published or accepted for publication in paying short story anthologies, magazines, blogs, audio books and podcasts. Some of his unpublished stories have also received “honorable mentions” from a number of publications. A collection of some of his short stories, The Satchel and Other Terrors, is scheduled for publication in February 2023.  Eloy González Argüelles was born in La Habana, Cuba, and came to the United States in 1961. His studies culminated in a PhD in Romance Languages at the Ohio State University. He taught at Wheaton College (Norton, Massachusetts) and the University of Massachusetts (Harbour Campus) before moving to Washington State University (WSU), where he taught Spanish literature and literary criticism for 38 years. For ten of his last twelve years before retirement he was Chair of the Department of Foreign Languages and Cultures at WSU. His output includes a novel, a book on the chivalric novel, and articles in scholarly journals and conference presentations. Upon retirement he became an Emeritus Professor at WSU.

0 Comments

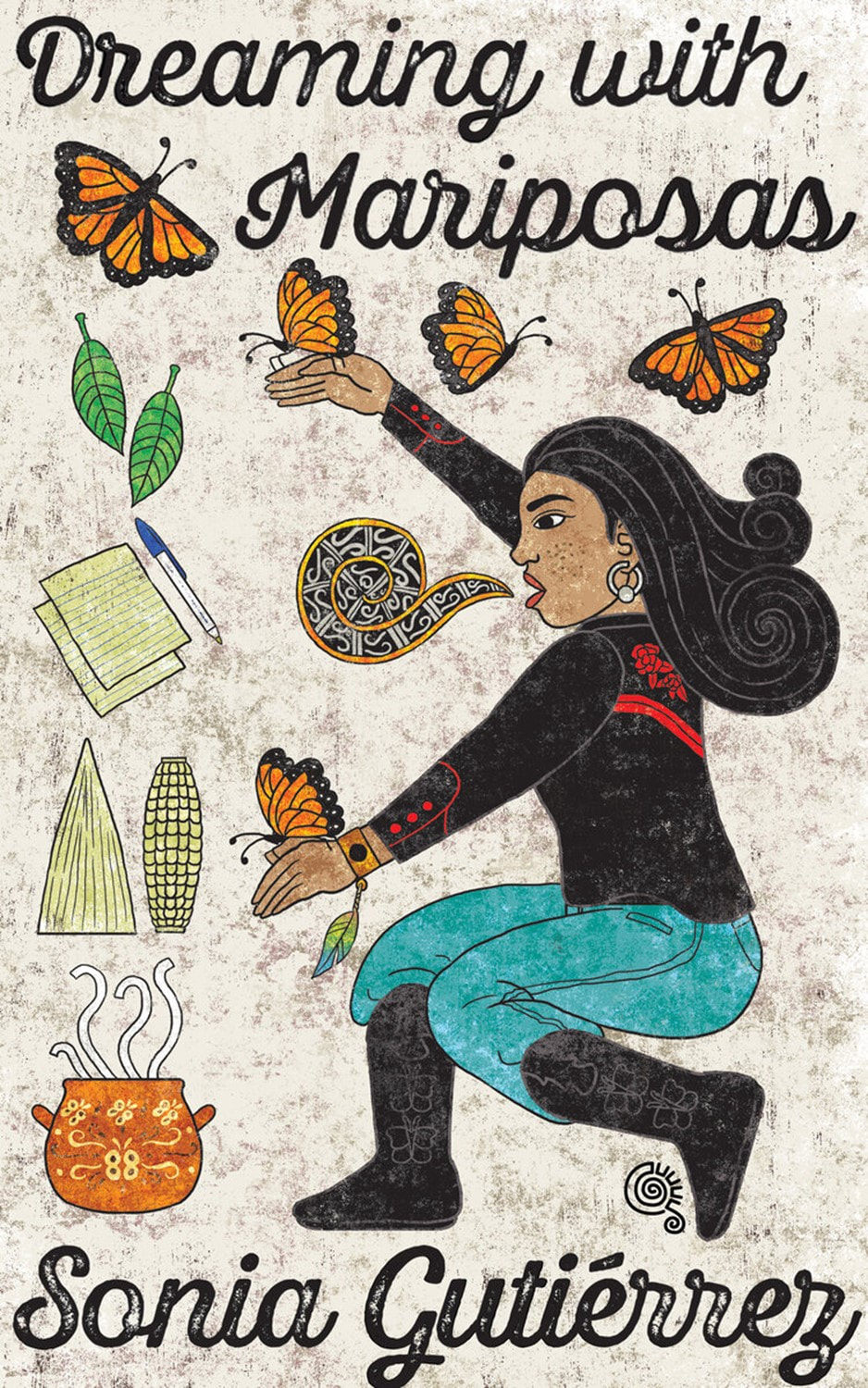

A Quiet Night on the Boulevardby Jacob Teran The block was not as active tonight. Olympic Boulevard is one of the gateways to enter our urban domain known as South Sapro Street and, on this night, it is absent of travelers and hostile combatants. You can hear the last metro bus making its way down the Boulevard to the depot drop off—final destination. A long day of picking up hard workers, tweakers, cholos, and dropping them off to where they need to go. Neither juras pass by with sirens, nor local tweakers roam the block looking for a potential vehicle to break into, just, the calm and quiet sound of the wind and train that makes its presence known to our barrio. These nights seldomly visit my barrio and when the sweet sound of silence makes its way to Sapro, the tranquility is always welcomed. I am in my messy room of my mom’s 2-bedroom apartment that I have not cleaned for days, lying in bed. I can feel the temperature drop from my open window as the smell of rain and burnt cannabis roaches permeates my room. I slip on my already tied DVS skating shoes, grab my hoodie, and make my way out into the abyss of my barrio. I head to the local Valero Gas Station to pick up a blunt wrap to indulge with my homeboy, Iggy. A light haze of cool droplets penetrates the dark sky making the lonely night that much colder. The smell of wet asphalt is refreshing with each sloshing step that I take. The local Valero was the place to buy a 3-pack of some cheap beer if no one was in the mood to go to Superior Market. The fluorescent lights beam blue and yellow, and read, “Valero Gas Station” with the “o” turned off or perhaps, dead. The people inside know me and even though I am still a minor by age, they never card me when I buy a pack of frajos, especially blunt wraps. As I make my way back on the wet asphalt of the Boulevard, I can smell and hear all sorts of familiar elements that ignite my senses. Across the street from the Valero was Cedar Ave. Someone was always washing their clothes on the corner of Cedar and the Boulevard in the evening. An old steel clothesline is engulfed with colorful socks, white t-shirts, and blue jeans. Probably a small family since I always see a group of three to four kids playing in the street just before the sun sets. The scent of Suavitel Fabric Softener always reminded me of my Abuelos in Boyle Heights, as their neighbors used a similar product for their clothes. The next thing I immediately notice is the fresh scent of cannabis burning nearby. It must be the homies from my block congregating at Cheddar’s pad since he lived two houses from the corner of Cedar. The thick skunky aroma of indica burning in the street at night always felt like I was home—a comforting feeling. Suavitel and marijuana were the telltale signs I am home. Between Cedar and Sapro, an area on the Boulevard, is where I feel the most alone as I walk. As I walk pass Cedar, I look to the left side of the Boulevard stretches to its desolate side of abandoned buildings bathed with graffiti. To my right was a long fence of white wood that closed off the side of an apartment. This wooden canvas is marked “SLS,” for SAPRO LOCOS, the acronym for the locotes on my street. Other times, they were crossed out by the rival barrios in the surrounding area and down south of us, passing the railroad tracks, beyond the Boulevard and away from the domain of Sapro. The spray on walls, scribes on windows, markings on wooden fences, trees, light posts, and curbsides, are all voices without faces that speak. A language that only people that live here understand. I walk under the streetlight between Cedar and Sapro, probably the most remote section of the Boulevard where peculiar occurrences would take place. In this desolate part of the Boulevard, voices could be heard with not a single person around, tall, shadowy figures have followed people only to disappear in a blink of an eye, and the streetlight itself would flicker violently when someone walked under. I could never account for the first two things that homies and neighbors have spoken of, but the streetlight flickering, that was real. Probably some glitch with the wiring under the asphalt, but, whatever rationale could explain, it always made me feel like some ominous entity was following me. I walk under it tonight. It does not flicker. I pass by the streetlight and eventually the Cliff to walk across Sapro to a dark grey Astro van. I could see the radio’s light slightly brighter as I approach the van’s sliding door. I knocked on it twice before opening it to be greeted by my homeboy, Iggy, “Fuckin’ Guill! Finally! Ah Ah! Ah!” Iggy’s laugh was always amusing. Iggy or Iggs, always sounded like his laugh was backwards. “’Sup G, was’ crackin’?” Coming into the van, we shake hands. “Nada güey, posted trying to get faded. ’Sup with you? Where da bud at?” “Shit, I thought you had it.” “Lying ass vato! Ah! Ah! Ah!” I pop out the grape flavored swisher I bought from Valero as I come in slamming the sliding door after me. “Firme! Grape will go good with this shit.” Iggy starts cutting up the swisher with a dull razor as I begin to break up the sticky indica from the baggie I was clenching since the odd streetlight. Iggy hands me a ripped Home Depot cardboard he used to dump out the tobacco from the swisher. Bone Thugs’ “Resurrection” is playing in a CD player he installed for his mom’s van’s radio. The music suits the quiet night and the session we are about to have. The dank bud begins to stink up the van with a skunky aroma as I break up the sticky flower that sticks to my fingertips. We start conversing about the extracurricular activities that have been making the block hot: South Siders and Veil Street have been coming through our block and hitting up their placas in our area. A few tweakers from a few blocks away stealing the vecinos’ recyclables. Really typical mamadas that occur in our barrio. Sometimes we laugh about it. Sometimes we get into heavier conversations. I hand the cardboard with the potent shake I just broke up to Iggy, “Trip out G, isn’t tonight quiet as fuck?” “Fuck yea, Guill…but…” Iggy licks the wrap’s end to seal the blunt, “…it’s firme, I like nights like this. Don’t you?” “Yeah, it’s just trippy,” I kept looking down the Boulevard from the second-row window of the van. Usually, a suspicious car or jura patrolling would pass, but nothing. Iggy hands me the lighter, “Do the honors and spark it up, Guill! Ah! Ah! Ah!” I light one side of the blunt and roll it around slowly as if I’m hot roasting a pig, making sure the cherry got an even burn. I take a couple of light hits as if I was smoking a cigar to get the cherry just right. As the smoke enters my lungs, I can feel it spread throughout my chest making me want to cough. I hold it in and exhale through my nostrils, feeling the euphoria of both weed and Krayzie Bone’s lyricism. Iggy is chain-hitting the blunt and seemed like he forgot I was in the session with him. He looks halfway towards me from the driver’s seat, “…Guill, I wanna tell you some shit that some OG told me a while back. This vato was a firme ass foo, a real one. The shit he said was the truth dog, palabra, and I still believe this shit to this day.” I looked at Iggy thinking ahh shit, this foo is faded. “Handles, G.” Iggy put the blunt down to his chest as it continues to burn, “And I don’t give a fuck what anyone says, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise either. You gotta believe this shit, Guillermo. You’re gonna have foos try to press you, call you a bitch and all that…but fuck that.” I was thinking, Iggy is never going to get to the point, “Yeah Iggy, handles, I hear you foo.” Iggy turns as much as he could to the seat behind him where I’m sitting, “You don’t got to be from nowhere and still be G wid’ it. A lot of foos think you gotta be from somewhere to be hard, claim a hood, get into mamadas and put in dirt, and all that bullshit, but chales, güey.” He pauses and takes another rip from the blunt. “Escucha güey…Just be you dog…and that’s keeping it gangster.” A bit of mota and street wisdom Iggy shares as he takes one big rip and lets out a huge cloud of smoke that makes him start choking and laughing. Iggs passed the almost finished blunt back to me as he was coughing all over the place. “Damn, foo, you aight, haha!” “Hit that shi…that shit…Mem…” Iggy kept coughing and all I could think about was why he was telling me this. I sit there as Iggy is coughing his lungs out and felt this was the most genuine thing my homeboy ever told me. Growing up in the hood, I always thought I would eventually get jumped in the hood when the time came. But what Iggy just confided hit me profoundly. I couldn’t stop thinking about it during our session. We kill the blunt and hear a few of Iggy’s primos coming back to interrupt our private hotbox. Fuck. Who is this? There are a chingo of us on the block and whoever comes to a session either has weed or none. “Eeeeee, look at you scandolosos right here,” Iggy’s primo Fat Boy always loves putting people on blast. Iggy looks up and blasts back, “fuck you dick, where were you when I hit you up earlier to blaze it?” Fat Boy smirks. “Don’t even trip, I share my shit homie, not like you assholes,” Fat Boy starts opening up a bag with his own weed that he had. Looking to me, Fat Boy laughs, “’Sup Memo, where’s all da bud at? You and Iggy are straight holdouts.” I smirk and laugh. “Dick, you foos had your own VIP sesh, so Iggs hit me up. Got ends? Still have some leftover yesca.” Fat Boy ignores me as his brother Scraps and Cheddar come through pushing themselves in the van talking mumbling and complaining that Iggy and I were smoking without them, although they just smoked without Iggy and me. “Hey dick, my Jefa is gonna come out trippin’ with all you foos in here being all loud and shit,” Iggy always snapped when unexpected dudes came, even if they were his primos. “Don’t even trip, my Tía loves me,” Fat Boy said as he was breaking up some of his bud nudging me for the cardboard with the leftover bud on it. “Not you fat ass, you’re burning the spot,” Iggy capped back as he was looking for a track to play on the van’s CD player stereo. Scraps, Cheddar, and I all started busting up laughing from the exchange between Iggy and his primo, Fat Boy. DJ Quik’s “Pitch in On a Party” surrounds the van’s speakers as the van gets louder and I kept thinking about what Iggy told me. Fat Boy looked back at Scraps and Cheddar, “Shut the fuck up turkey and you too cheddar.” Fat Boy’s hermano Scraps was chubby like Fat Boy, but shorter. Everyone called him “Turkey” or “Danny DeVito,” which he hated. Cheddar had pretty poor hygiene when it came to his teeth. He never brushed his teeth, and the result made his dientes look like picante corn nuts. “Dick, you’re fucked up,” Cheddar shakes his head. “You’re a scandalous vato too, ‘Gay-mo,’” Fat Boy looks to me. The homies would either call me “Guill” or “Memo,” short for Guillermo. Other times, “Gay-mo,” because it sounded funny to them, and I also hated it. “Just be you dog,” I pat Fat Boy hard on the back of the shoulder. “Fuck, let’s go finish this shit out in the front of your pad Fat Boy, you burned the spot.” “Fuck it, let’s bounce then,” Fat Boy said as we all get up to leave the van. We all walked to the front of Fat Boy and Scrap’s pad. Their mom was asleep, so we had to creep and crawl if we didn’t want to get kicked out of the yard. Fat Boy and Scrap’s oldest brother Beaker wasn’t home either, probably getting all pedo with some lady that he would always say he was going to marry but then break up with weeks later. We all post up on the bed of Beaker’s 1987 El Camino, laughing quietly, talking about how cold the night was. We start packing bowls from Cheddar and Scrap’s weed pipes and begin a new rotation. Iggy’s stomach was bothering him, so heads to the restroom. The four of us, without Iggy, sit in the back of the El Camino getting faded as the night continues to get colder and quieter. Suddenly, a car comes out the cut from the corner of the yard where we are posting up, on the Boulevard. Fat Boy and Scraps lived at the corner of our street and had thick bushes that made it hard to see who was walking or driving by, especially at night. * * * * We then see four shadows running around the corner of Fat Boy and Scraps’ pad outside the fence. The moonlight was our only aid in seeing through the darkness. One shadow stood at the corner keeping trucha, while one other dude stood outside of the gate. The other two shadows came up to us in front of the fence where we happen to be sitting. “Where the fuck you from, Ese?! This is big bad Southside Greenwood Gang! Fuck ‘Scrape’ Street!” The bald shadow brandishes a .45 cuete and points it to each of our stunned skulls. All of us with our sweaty palms open, shield our chests, afraid and frozen in an already cold evening. The nefarious shadow, only three feet away from the silver diamond-shaped fence that separates us, stands fiercely. The streetlight reveals his inked face, a black spider web trapped his entire face with the center of the web starting from the shadow’s nose. Eyes as black as obsidian, stabbing us with his soulless glare, listo for anything. “Hey dog…we’re from nowhere…we don’t bang. I live right here,” Fat Boy being the oldest of us speaks, shaken up, choosing his words carefully. The shadow looks at him with disdain and then all of us. He points his cuete at each of us asking us individually if we claimed Sapro Street. With our arms raised, palms open, not knowing what to think or do, we deny because we are in fact not from the hood, yet. “I don’t give a fuck! You’re caught slipping out here! This is Southside Territory! Fuck Sapro Street! Bitch ass levas! The spider webbed shadow looks to his homeboy for confirmation to off us right then and there. The shadow raises his less dominant hand and cocks his cuete. Coming back from the restroom, Iggy comes out to a situation he was somewhat familiar with. The second shadow by the fence gate sees Iggy and hails out, “Who the fuck are you?! Southside Greenwood Gang, ese!” Iggy opens his palms towards the second shadow, “Hey, I don’t bang dog. I live right here in the back, this is my Tía’s pad. These are all my primos, we’re just right here burning some bud. My primos are kids G, they ain’t soldiers. We are family right here.” Iggy being much older than us already knew the street lingo—along with his street intellect and rhetoric, Iggy’s response disheartens the shadows. Although this was a typical night in my barrio, we never had a neighboring group roll up on us like that. This night made me realize the brevity of life, the choices I make and the words I choose influence what can happen next. Iggy’s words echoed in my mind and made me realize a lot of shit—life is short and can be taken in an instant. I want to change and do better, but it’s difficult when you have no direction or positive influences. But Iggy made me think and that was perhaps one of the most impactful things someone ever told me. The dude with the cuete throws up his insignia, claims his hood one last time so we could all remember it, and dashes off to the car with the other shadows and drove off into the abyss. The rain never came but the smell remained…Some fuckin’ quiet night.  Jacob “Jake” Teran is a proud Chicano living in the San Gabriel Valley, Los Angeles. Jake is a 2nd generation Chicano who was born in Montebello, Los Angeles, east of Los Angeles. He has published one short fictional story at his community college at Rio Hondo College and a master’s thesis for his graduate program, where he obtained his Masters Degree in Rhetoric and Composition. He is currently teaching composition to several departments in two colleges that include indigenous and Chicanx literature. Jake currently lives in the San Gabriel Valley where he is working on a novel based on his experiences growing up in his barrio that deals with gang lifestyle, drugs, violence, and finding one’s identity in a chaotic concrete jungle. FlowerSong Press in McAllen, Texas, recently published Sonia Gutiérrez's novel, Dreaming with Mariposas, winner of the Tomás Rivera Book Award 2021. Read an excerpt below. Order a copy from FlowerSong Press. Our Doctor Who Lived in Another Country Whenever Paloma, Crucito, and I got so sick Mom couldn’t heal us with her herb-filled cabinets, an egg, or Vaporú, we had to wait for the week to hurry up, so Dad could take us on a trip to visit our doctor who lived in another country. We crossed the border to a familiar place called Tijuana, Baja California, México. Estados Unidos Mexicanos—the United Mexican States—said the large shiny Mexican pesos in Spanish. With her miracle stethoscope, our doctor’s Superwoman eyes and Jesus hands always found where the illness hid. As our father drove into Tijuana, the city looked like an expensive box of crayons. Fuchsia and lime green colors hugged buildings. Dad parked our shiny Monte Carlo the color of caramelo on the third floor of a yellow parking facility, and we walked down a cement staircase and crossed onto Avenida Niños Héroes. Then, we went up peach marble stairs and entered our doctor’s waiting room. On the weekends, patients from faraway cities like Los Ángeles and San Bernardino came to see La Doctora. Judging from the looks of some of the patients’ faces, they were there to see the doctor’s husband, who was a dentist. They made the perfect couple—the doctor and the dentist—for both their Mexican and American patients. The doctor, a tall woman with smoky eye shadow, looked directly into her patients’ eyes when she spoke. Not like some American doctors in the U.S. who didn’t look at Mom because she only spoke Spanish. On one of those doctor visits, I heard the dentist, a tall, burly man with a mustache that looked like a broom, speak English on the telephone with a patient. “John, you need to come in, so I can take a look at your tooth.” Another time I saw an elderly gringo, waiting for his wife, seeking the dentist’s services. That’s when I realized the other side was expensive for them too. When we were done at the doctor’s office, our next stop was El Mercadito on the other side of the block on Calle Benito Juárez. Churros sprinkled with sugar and cinnamon in metal washtubs rested on the shoulders of vendors. Fruit cocktail and corn carts were closer to the sidelines of streets, so passersby could make full stops and buy their favorite pleasure bombs to the taste buds. During summer visits to Tijuana, Paloma ate as much mango as she wanted because fruit was affordable in México. My weakness was corn. And even if I felt sick, I always looked forward to eating a cup of corn topped with butter, grated cheese, lemon, chili powder, and salt. Mexican corn didn’t taste like the sweet corn kernels from a tin can—Mexican corn tasted like elote. Approaching El Mercadito, dazed bees were everywhere. Mother warned us about not harassing bees. Because according to Mom, bees were like us—like butterflies. “Without bees, our world would not be as beautiful and delicious. Bees are sacred, and without them, we wouldn’t exist. Paloma and Chofi, please don’t ever hurt bees,” Mom said as we walked by our fuzzy relatives and nodded in agreement. The smell of camote, cilacayote, cajeta, and cocadas added to the blend of enticing smells at the open market, where we roamed with buzzing bees peacefully. Colorful star piñatas and piñata dolls of El Chavo, La Chilindrina, and Spiderman hung along the tall ceiling, and the familiar smell of queso seco filled the air heavy with delight. Wooden spoons, cazos made of copper, molcajetes, loterias, pinto beans, Peruvian beans, and tamarindo provided such a wide selection of merchandise vendors didn’t have to fight over customers. Politely, they asked, “What can I give you?” or “How much can I give you?” as we walked by. In Tijuana, street vendors sold homemade remedies for just about anything imaginable. “This cream here will alleviate the itch that doesn’t let your feet rest,” and “For a urine infection, drink this tea,” vendors hollered. And then there were the funny concoctions, for which even I, a girl my age, didn’t believe their miracle powers: “For the loss of hair, use this cream that comes all the way from the Amazon Islands.” Hand in hand with our familia, Paloma and I walked the streets of Tijuana with our sandwich bag full of pennies and nickels. We gave our change to children who extended their little palms up in the air. Mom would take a bag full of clothing and find someone to give it to, which I never understood, because most people on the streets dressed just like us, from the pharmacists to children wearing school uniforms. Once, when we were walking in Tijuana, Paloma and I saw a man with no legs riding what looked like a man-made skateboard instead of a wheelchair. Our eyes agreed; the man needed the rest of our change. Besides the rumors about Tijuana being a dangerous place, nothing ever happened to our car or Mom’s purse. In Tijuana, doctors had saved Crucito’s life because my parents knew, if they took Crucito to a hospital in the U.S., he might not come out alive because American doctors wouldn’t try hard enough for a little brown baby like my little brother. In Tijuana, our parents spoiled us with goodies and haircuts at the beauty salon. And I felt bad for Americans who couldn’t afford a doctor and didn’t have a good doctor or a dentist like ours in El Otro Lado—on the Mexican side. Pobrecitos gringos. Launderland “. . . Girls--to do the dishes Girls--to clean up my room Girls--to do the laundry Girls--and in the bathroom . . .” —The Beastie Boys, “Girls” Because we couldn’t afford a fancy steam iron, Mom was very practical. Instead of using a plastic spray bottle, she sprayed Dad’s dress shirts, including other garments with her mouth. She gracefully spat on each garment lying on el burro. Ironing was always an all-nighter that seemed endless and agonizing. I hated ironing Dad’s Sunday dress shirts—or anything, requiring special care and Mom’s supervisory instructions. There were two chores I hated most about being a girl: ironing and washing someone else’s clothes. The piles and piles of Dad and Mom’s dress clothes on top of our clothes seemed endless. (Thank God Father worked in construction or else long sleeve dress shirts would have added more to the pile). As soon as Mom started setting up el burro—the ironing board—in what should have been half a dining room, but instead we used as a bedroom, I began my whining. “Mom, but why do Paloma and I have to iron Dad’s clothes?” “¡Ay Sofia! You’re so lazy!” “It’s just that I don’t understand. I don’t wear Dad’s clothes. Why us?” “Sofia, are you going to start? That mouth! ¡No seas tan preguntona! You always ask too many questions! You always talk back! That tongue of yours. Where did you learn those ways‽” When I nagged, my mother’s facial gestures expressed her disappointment, and she turned her face away from me. What had she done to deserve such a lazy daughter like myself? With a cold bitter laugh, Mom responded, “Because he’s your father,” which I never understood. Having to live in apartments also meant we needed to fight over laundromat visitation rights. If anybody left their clothing unattended and the dryer or washer cycle ended, Paloma had to spy to check if anyone was coming, and I’d quickly take out the clothing and place it on a folding table. I’d throw our clothes inside the washer or dryer, and then we’d run to our apartment; otherwise, we’d be washing and drying all day. When we moved from Vista to San Marcos, that’s when I noticed chores strategically favored the man in our family. For instance, we girls never carried out the trash like Dad—just heavy laundry baskets mounted with dirty clothes. To me, mowing the lawn didn’t look difficult at all. It looked super easy and fun. How to Mow the Long Green Grass By Chofi Martinez 1) Check the lawn for Crucito’s toys, Dad’s nails, and any other sharp objects, including rocks. 2) Add gasoline. 3) Turn the lawn mower’s switch ON. 4) Press on the red jelly like button several times. 5) Pull the starter a couple of times. 6) Push the lawn mower with all your human strength. If I could mow the lawn like a boy, at least I could be outside and listen to the singsong of finches, watch white butterflies flutter through the garden, greet and wave at neighbors passing by, and stare at the endless blue sky. But instead of Paloma and me mowing the lawn, Dad dropped us off at the laundromat on Mission Avenue next to the dairy to wash and fold everything from heavy king-sized Korean blankets to Dad’s dirty and not so white underwear. Bras and underwear were the most embarrassing garments to dry, especially when red stained or not so new underwear fell to the ground, while we checked the clothes in the dryer. If an undergarment accidentally fell, it’s not like we could ignore it and just leave it there when it was clear we were watching each other. For us, if someone looked at our bra or underwear, it was as if they were looking at our naked bodies. It was equivalent to watching feminine hygiene commercials in front of boys or even worse—Dad. Oh my God! ¡Trágame tierra! Sometimes, when we barely had enough quarters and single dollar bills to spare in our imitation Ziploc bag, I’d window shop at the vending machine with its snacks and cigarettes then stare and admire the package labels with the bright oranges and mustardy yellows. While we waited for the washer to end, we sat on the orange laundromat chairs (bolted to the ground in case anyone tried to steal them, I figured). My eyes wandered—at the graffiti, the announcements, the tile floor that needed a broom and a mop, the Spanish newspapers with the sexy ladies with their back to the readers wearing a two piece—a thong and high heels and the constant drop off and pick up of wives and daughters. Swinging my feet back and forth out of boredom, I stared at the dryer’s circular-glass door with the thick-black trim, where garments would slowly go round and round and round and round, painting a picture of a vanilla and chocolate ice cream swirl, which was like meditating in front of a TV screen. Another dryer gave form to a motley of colors from the palette of Matisse’s bright yellows, blacks, oranges and greens Ms. Watson, my art teacher, had lectured on. And then, the dryer came to a full stop, and the colors—the burgundy red and thorny pink roses and the stoic lion—on heavy blankets took their true forms in need of folding. Our Dream Home Mom and Dad were always working for our dream house. In his early twenties, dressed in slacks and a tie, José Armando, our real estate agent, came to our apartment and talked to my parents about becoming homeowners. He sat patiently for what felt like hours translating endless paperwork. José Armando, Tijuana born with Sinaloa roots, grew up in Carlsbad, “Carlos Malos.” He smelled like a professional, and the heaviness of his cologne and starchy clothes filled our small kitchen and living room long after he was gone. Our real estate agent felt like familia. “Helena and Francisco, the contract states that if you complete all the renovations within a year, the bank will approve the loan. You can move in now, but the house is not in living conditions.” “But Jose Armando, I’m sure you’ve heard stories--what if the gringo doesn’t keep his promise?” Mom asked our real estate agent. “Helena, please trust me. Mr. Stoddard is a good man and will not back out of the deal because he signed the contract,” José Armando assured Mom the owner would follow through. “You know Francisco more than I do. Your husband is going to make the house look like a palace—like your dream home. Helena, the property even has a water well. You can add the roses, calla lilies, and fruit trees you’re looking for in a property. And, most importantly, you won’t have to commute from Vista to San Marcos anymore.” Where Dad and Mom came from, waiting periods to build a house didn’t exist; people didn’t need permits to build a home made from adobe or blocks. In the U.S., however, my parents had to settle for a fixer-upper Dad could mend in no time with the help of family and friends. When José Armando finally struck a deal with the owner, it took Dad a whole year to claim the house on 368 West San Marcos Boulevard as our own. After Dad came home from working construction all day, he’d work at home. Mom must have had sleepless nights when Father agreed to buy our first house. That’s because Mother didn’t see what Father saw. We would have a street number to ourselves, 368. The first days at 368, Mom refused to eat in the kitchen, and how could she eat in there? How could her children eat in that thing Dad called kitchen? Yes, the house included a small stove, but cockroaches were baking their own feasts in the oven. Dad imagined a swing set for Crucito in the backyard’s green lawn. But Mother had heard the neighbors walking by say the backyard turned into a swamp during the rainy seasons. Dad imagined a one-foot swallow lined with miniature plants that would keep the water moving to the large apartment complex next door. But Mom saw the swamp at our feet. Dad imagined the pantry and mom’s new wooden cupboards. But Mom saw mice and cockroaches. Lots of cockroaches. Mom saw the faded dilapidated and peeling mint green paint. Dad saw a new wooden exterior and a fresh coat of paint. Our new but old kitchen was infested with silky brown cockroaches—the thin kind that matched the plywood. Underneath the crawl space lived the critters, and at night, big roaches squeezed and welcomed themselves in through both the front and back door to drink water and eat crumbs. Paloma and I, in our superhero capes, made from black trash bags, became Las Cucaracha Warriors de la Noche and ran after the cucaracha bandits. We routinely turned off the lights, and then at about ten o’clockish, Mom turned on the kitchen lights, and Paloma and I charged at them. While they scattered everywhere, we all took our turns killing the horde of nightly visitors. The pest problem at 368 went away with endless nights of Raid attacks and hot water splashing. Paloma and I even conquered our cockroach phobia and squished cockroaches with our very own index fingers. The master bedroom had seven layers of dusty carpets pancaked on top of each other. The wooden floor in our living room held itself together miraculously—we were always careful to wear shoes to prevent any splinters from pricking our bare feet. When we finally settled into our new home, one Saturday morning Paloma and I still in our pajamas were arguing over who would have to sweep and mop before our parents got home from work when suddenly we found ourselves shoving and wrestling each other. And then with a big push, the unexpected happened. I flew through the wall. “Oh my God, Chofi! Look what you did!” “Look what I did? You pushed me, Mensa!” Paloma and I had to reconcile immediately to cover up the crime scene. When Dad got home later that afternoon and walked through the hallway to inspect our chores, he demanded an explanation, “¿Y este pinche sofá? ¿Qué está haciendo aquí?” Chanfles, we thought as our eyes placed the blame on each other. Dad gave us the mean Martinez Castillo stare with the white of his eyes showing that always worked, shook his head, and stormed out of the house because Dad knew he had to replace all the house’s old plywood with new drywall. Our idea of placing a love seat in front of the hole to cover it up didn’t work. Our fear for our father’s punishment turned into giggles and then uncontrollable laughter. Poking at each other’s ribs and yelling at each other, “It’s your fault!” and “No, it’s your fault!” we almost peed our underwear. We laughed at the hole in the wall, the sofa that barely fit in the hallway that must have looked ridiculously out of place in our father’s eyes, and at our new but old house facing the boulevard. Strangers driving by honked or waved and gave Dad a thumbs up when he worked on our house on the weekends. We were living in Father’s dream home, and we were happy. José Armando, our real estate agent, was right—Dad fixed our house, and Mother created her garden of dreams, where Dad and Mom planted hierbas santas. Orange, avocado, peach, cherimoya, guava, and purple fig trees. And native yellow-orange, deep-purple, and rose-colored milkweeds for our butterfly relatives who passed by and travelled south to Michoacán, our parents’ homeland. One day we would follow them if Mom and Dad worked hard and saved enough money. One day. The Guayaba Tree In San Marcos, our backyard smelled like Idaho. The familiar smell of manure from the Hollandia Dairy on Mission Avenue lingered in our backyard. Months before the guava tree joined us at San Marcos Boulevard, Mom took free manure from the dairy for our garden and prepared the earth with water. Even if we already had a few trees, Dad and Mom talked about the trees and plants with special powers that would join our family. Next to the guayaba tree’s new home, the apricot tree had already joined us, and now it was the guava tree’s turn to step out of its black plastic container and to spread its roots and branches. At the end of the week with their Friday paycheck, Mom and Dad’s eyes were set on an árbol de guayaba. Right after work Dad drove us to the northside of San Marcos on the winding road to Los Arboleros, the tree growers’ ranch on East Twin Oaks Valley Road, to buy the perfect tree for our backyard. As we approached a dirt road leading to the Santiago property, Don José in his sombrero and red and yellow Mexican bandana tied around his neck waved at us. At his side, two large Mexican wolfdogs with imposing orange eyes barked at us as we approached the nursery next to their house. “Paloma and Chofi, be careful with Don Jose’s dogs.” “Okay Ma,” we answered in unison. “Buenas tardes, Francisco and Helena. Don’t worry, Señora Helena. My calupohs don’t bite unless they smell evil. They scare off the coyotes that want to get into the chicken coop. Last week a red-shouldered hawk snatched one of my María’s chickens in broad daylight.” Don José’s dogs, Yolotl and Yolotzin, sniffed our stiff bodies while I prayed to San Jorge Bendito: “San Jorge Bendito, amarra tus animalitos . . . .” Yolonzin sniffed and licked my hand. Thankfully, Don José’s calupohs remembered us; we were in the clear. “If you need anything, holler at me. I’m going to water the foxtail palm trees on the other side.” At Don José and Doña María de la Luz Santiago’s small ranch, Paloma and I were careful not to step on rattlesnakes. We walked through the rows of small trees in 15″ containers and played with sticks next to a large flat boulder with smooth holes. I filled the holes with dead leaves and dirt and mixed it with a stick. “Paloma, let’s ask Don Jose about the holes on this large boulder. How do you think these holes got here?” Paloma shrugged her shoulders and signaled with her head to get back. With the calupohs following us, we found Mom and Dad still deciding on a tree and a crimson red climbing rose bush. “But Pancho, look how green the leaves look on this one!” “Yes, Helena, but look at this one. It has a strong tree trunk.” “Pancho, this one has ripe fruit! Smell it, Pancho. With time, this one will be strong too.” “You’re right, Helena. We can take the one you want. Let’s pay Don Jose and get going before it gets too dark, so we can plant our tree today.” “Yes, Pancho, it’s a full moon!” “Paloma and Chofi, I’m glad you’re both back. Go look for Don Jose, and tell him we’re ready to pay.” Paloma and I ran to look for Don José. On our way to find him, I remembered we needed to ask him about the holes on the boulder. “Hola Don Jose. My mom and dad are ready to pay.” “Let’s go then.” “Don Jose, we have a question for you. We saw a big flat rock on your property, and we’re wondering how the holes got there.” Don José cleaned his sweat with his bandana and gave us a pensive look. “Those holes. Well, Chofi, as you may know, this land you see here from Oceanside all the way to Palomar Mountain and beyond was inhabited by Native people. Women sat and pounded acorns on metates like the one you saw and made soup and other foods. You can only imagine how many years it took for those indentations to leave their mark and to withstand time. Those women, Chofi and Paloma, left their mark.” “Oh, wow, Don Jose. That’s why the road is called Twin Oaks Valley Road? It’s a reference to Native people’s trees, who lived in this area?” “Yes, Chofi and Paloma. Native people still live on these lands—in Escondido, San Marcos, Valley Center, Fallbrook, Pala, and Pauma Valley and beyond. Ask your U.S. history teacher about the people who inhabited these lands. I’m sure they can tell you more.” “Thank you, Don Jose. I’ll ask.” Dad and Mom paid Don José, and off we went to plant our guayaba tree. With our guava tree sticking out of the window in the Monte Carlo and lying on Paloma, Crucito, and me in the back seat, Mom was all smiles and kept glancing back. “Pancho, please drive slowly and turn on your emergency lights. Children, hold onto our tree carefully.” “Don’t worry Helena. Two more stop lights, and we’re almost home.” Dad agreed to Mom’s pick because he knew she loved guayabas—all kinds. This time they chose the one with the two guayabas with pink insides, which wasn’t too sweet and just about my height. I preferred the bigger trees at Los Arboleros. Why couldn’t we get bigger trees? Mom and Dad always chose the smaller trees because those were the ones we could afford, and plus we didn’t have a truck like our neighbor Don Cipriano’s, but maybe we could borrow it next time. As soon as we arrived home, Dad cut the container down the middle with a switchblade, and Mom pushed the shovel down with her right foot and split the earth. “¡Ay, ay! ¡Ay Pancho! Be careful with the tree’s roots. Here, grab the shovel. Let me hold onto the arbolito.” Dad dug the hole, exposing the dark brown of the earth as two pink worms shied away from the light. “Dad, can Crucito and me get the worms, pleaseee?” “Hurry up Chofi and Cruz. Go ahead. Your mom and I want to plant the tree today.” “Okay, Apá!” While I carefully took the worms from their home, Mom held the guava tree as if she held a wounded soldier and whispered to the tree, “Arbolito, don’t worry. You’re going to be safe here. I’m going to water you when you get thirsty and take care of you—we all will.” “Pancho, one day we’re going to make agua de guayaba.” “Sí, Helena, we’re going to make guayabate like the one my mom used to make. It was so good!” “I bet it was, Pancho. To prevent a bad cough, my mom used to give us guava tea to fight off the flu.” “Helena, did you know guava leaves are also good for hangovers?” “Ay Pancho. ¿Qué cosas dices? Let’s get this tree planted.” From the dried-up manure pile, Dad mixed the native soil and compost and pulled the weeds. As Mom placed the rootball above the hole, they both looked for the guava tree’s face and centered the tree on top of the hole. With the shovel, Dad poured the dirt around the tree. Mom took the shovel from Dad and pounded softly on the dirt surrounding the guava tree, making sure they left the edge below the surface. Next to the apricot tree with a woody surface, the small guava tree with tough dark green leaves would be heavy with fruit one day for our family, our neighbors, and friends. Dad went looking for a canopy for the young guava tree to protect her from winter’s threatening frostbite, and mom stood in the garden, admiring our new family member. It was time to return the worms to the earth; they were so tender but so strong. I made a little hole with my hand, placed the worms inside, said thank you to the worms, and covered them with dirt. The guayaba tree would make a perfect home.  Sonia Gutiérrez is the author of Spider Woman / La Mujer Araña (Olmeca Press, 2013) and the co-editor for The Writer’s Response (Cengage Learning, 2016). She teaches critical thinking and writing, and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. FlowerSong Press in McAllen, Texas, recently published her novel, Dreaming with Mariposas, winner of the Tomás Rivera Book Award 2021. Her bilingual poetry collection, Paper Birds / Pájaros de papel, is forthcoming in 2022. Presently, she is returning to her manuscript, Sana Sana Colita de Rana, working on her first picture book, The Adventures of a Burrito Flying Saucer, moderating Facebook’s Poets Responding, and teaching in cyberland. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed