Prologue: Saturday, October 4, 2003; |

|||||||

| excerpts_angels_in_the_wind__.pdf | |

| File Size: | 175 kb |

| File Type: | |

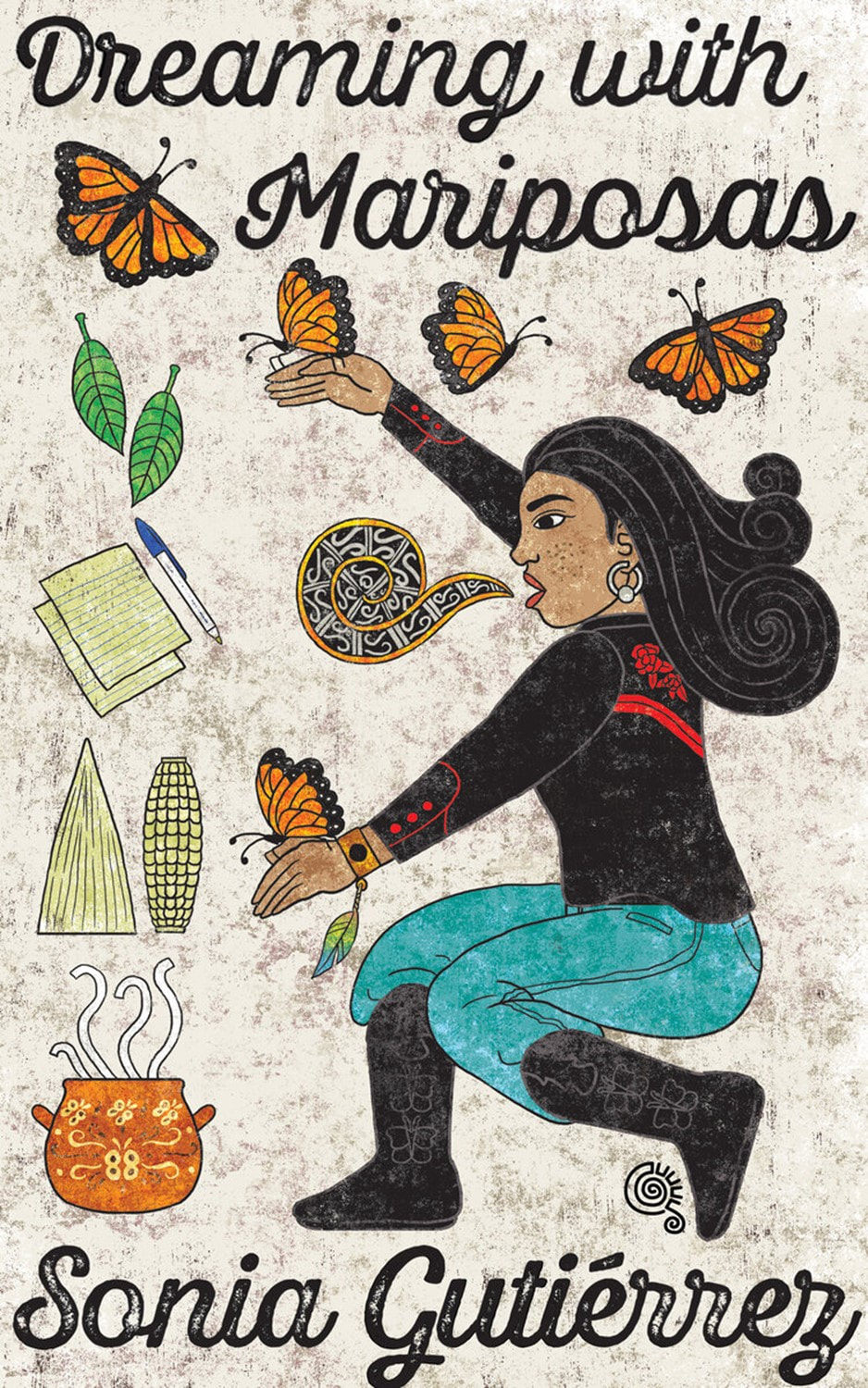

An excerpt from

Preparatory Notes for

Future Masterpieces

by Maceo Montoya

Whenever Paloma, Crucito, and I got so sick Mom couldn’t heal us with her herb-filled cabinets, an egg, or Vaporú, we had to wait for the week to hurry up, so Dad could take us on a trip to visit our doctor who lived in another country. We crossed the border to a familiar place called Tijuana, Baja California, México. Estados Unidos Mexicanos—the United Mexican States—said the large shiny Mexican pesos in Spanish. With her miracle stethoscope, our doctor’s Superwoman eyes and Jesus hands always found where the illness hid.

As our father drove into Tijuana, the city looked like an expensive box of crayons. Fuchsia and lime green colors hugged buildings. Dad parked our shiny Monte Carlo the color of caramelo on the third floor of a yellow parking facility, and we walked down a cement staircase and crossed onto Avenida Niños Héroes. Then, we went up peach marble stairs and entered our doctor’s waiting room.

On the weekends, patients from faraway cities like Los Ángeles and San Bernardino came to see La Doctora. Judging from the looks of some of the patients’ faces, they were there to see the doctor’s husband, who was a dentist. They made the perfect couple—the doctor and the dentist—for both their Mexican and American patients. The doctor, a tall woman with smoky eye shadow, looked directly into her patients’ eyes when she spoke. Not like some American doctors in the U.S. who didn’t look at Mom because she only spoke Spanish.

On one of those doctor visits, I heard the dentist, a tall, burly man with a mustache that looked like a broom, speak English on the telephone with a patient. “John, you need to come in, so I can take a look at your tooth.”

Another time I saw an elderly gringo, waiting for his wife, seeking the dentist’s services. That’s when I realized the other side was expensive for them too.

When we were done at the doctor’s office, our next stop was El Mercadito on the other side of the block on Calle Benito Juárez. Churros sprinkled with sugar and cinnamon in metal washtubs rested on the shoulders of vendors. Fruit cocktail and corn carts were closer to the sidelines of streets, so passersby could make full stops and buy their favorite pleasure bombs to the taste buds.

During summer visits to Tijuana, Paloma ate as much mango as she wanted because fruit was affordable in México. My weakness was corn. And even if I felt sick, I always looked forward to eating a cup of corn topped with butter, grated cheese, lemon, chili powder, and salt. Mexican corn didn’t taste like the sweet corn kernels from a tin can—Mexican corn tasted like elote.

Approaching El Mercadito, dazed bees were everywhere. Mother warned us about not harassing bees. Because according to Mom, bees were like us—like butterflies. “Without bees, our world would not be as beautiful and delicious. Bees are sacred, and without them, we wouldn’t exist. Paloma and Chofi, please don’t ever hurt bees,” Mom said as we walked by our fuzzy relatives and nodded in agreement.

The smell of camote, cilacayote, cajeta, and cocadas added to the blend of enticing smells at the open market, where we roamed with buzzing bees peacefully. Colorful star piñatas and piñata dolls of El Chavo, La Chilindrina, and Spiderman hung along the tall ceiling, and the familiar smell of queso seco filled the air heavy with delight. Wooden spoons, cazos made of copper, molcajetes, loterias, pinto beans, Peruvian beans, and tamarindo provided such a wide selection of merchandise vendors didn’t have to fight over customers. Politely, they asked, “What can I give you?” or “How much can I give you?” as we walked by.

In Tijuana, street vendors sold homemade remedies for just about anything imaginable. “This cream here will alleviate the itch that doesn’t let your feet rest,” and “For a urine infection, drink this tea,” vendors hollered. And then there were the funny concoctions, for which even I, a girl my age, didn’t believe their miracle powers: “For the loss of hair, use this cream that comes all the way from the Amazon Islands.”

Hand in hand with our familia, Paloma and I walked the streets of Tijuana with our sandwich bag full of pennies and nickels. We gave our change to children who extended their little palms up in the air. Mom would take a bag full of clothing and find someone to give it to, which I never understood, because most people on the streets dressed just like us, from the pharmacists to children wearing school uniforms.

Once, when we were walking in Tijuana, Paloma and I saw a man with no legs riding what looked like a man-made skateboard instead of a wheelchair. Our eyes agreed; the man needed the rest of our change.

Besides the rumors about Tijuana being a dangerous place, nothing ever happened to our car or Mom’s purse. In Tijuana, doctors had saved Crucito’s life because my parents knew, if they took Crucito to a hospital in the U.S., he might not come out alive because American doctors wouldn’t try hard enough for a little brown baby like my little brother. In Tijuana, our parents spoiled us with goodies and haircuts at the beauty salon. And I felt bad for Americans who couldn’t afford a doctor and didn’t have a good doctor or a dentist like ours in El Otro Lado—on the Mexican side. Pobrecitos gringos.

“. . . Girls--to do the dishes

Girls--to clean up my room

Girls--to do the laundry

Girls--and in the bathroom . . .”

—The Beastie Boys, “Girls”

Because we couldn’t afford a fancy steam iron, Mom was very practical. Instead of using a plastic spray bottle, she sprayed Dad’s dress shirts, including other garments with her mouth. She gracefully spat on each garment lying on el burro.

Ironing was always an all-nighter that seemed endless and agonizing. I hated ironing Dad’s Sunday dress shirts—or anything, requiring special care and Mom’s supervisory instructions.

There were two chores I hated most about being a girl: ironing and washing someone else’s clothes.

The piles and piles of Dad and Mom’s dress clothes on top of our clothes seemed endless. (Thank God Father worked in construction or else long sleeve dress shirts would have added more to the pile). As soon as Mom started setting up el burro—the ironing board—in what should have been half a dining room, but instead we used as a bedroom, I began my whining.

“Mom, but why do Paloma and I have to iron Dad’s clothes?”

“¡Ay Sofia! You’re so lazy!”

“It’s just that I don’t understand. I don’t wear Dad’s clothes. Why us?”

“Sofia, are you going to start? That mouth! ¡No seas tan preguntona! You always ask too many questions! You always talk back! That tongue of yours. Where did you learn those ways‽”

When I nagged, my mother’s facial gestures expressed her disappointment, and she turned her face away from me. What had she done to deserve such a lazy daughter like myself? With a cold bitter laugh, Mom responded, “Because he’s your father,” which I never understood.

Having to live in apartments also meant we needed to fight over laundromat visitation rights. If anybody left their clothing unattended and the dryer or washer cycle ended, Paloma had to spy to check if anyone was coming, and I’d quickly take out the clothing and place it on a folding table. I’d throw our clothes inside the washer or dryer, and then we’d run to our apartment; otherwise, we’d be washing and drying all day.

When we moved from Vista to San Marcos, that’s when I noticed chores strategically favored the man in our family. For instance, we girls never carried out the trash like Dad—just heavy laundry baskets mounted with dirty clothes. To me, mowing the lawn didn’t look difficult at all. It looked super easy and fun.

How to Mow the Long Green Grass

By Chofi Martinez

1) Check the lawn for Crucito’s toys, Dad’s nails,

and any other sharp objects, including rocks.

2) Add gasoline.

3) Turn the lawn mower’s switch ON.

4) Press on the red jelly like button several times.

5) Pull the starter a couple of times.

6) Push the lawn mower with all your human strength.

If I could mow the lawn like a boy, at least I could be outside and listen to the singsong of finches, watch white butterflies flutter through the garden, greet and wave at neighbors passing by, and stare at the endless blue sky. But instead of Paloma and me mowing the lawn, Dad dropped us off at the laundromat on Mission Avenue next to the dairy to wash and fold everything from heavy king-sized Korean blankets to Dad’s dirty and not so white underwear. Bras and underwear were the most embarrassing garments to dry, especially when red stained or not so new underwear fell to the ground, while we checked the clothes in the dryer. If an undergarment accidentally fell, it’s not like we could ignore it and just leave it there when it was clear we were watching each other. For us, if someone looked at our bra or underwear, it was as if they were looking at our naked bodies. It was equivalent to watching feminine hygiene commercials in front of boys or even worse—Dad. Oh my God! ¡Trágame tierra!

Sometimes, when we barely had enough quarters and single dollar bills to spare in our imitation Ziploc bag, I’d window shop at the vending machine with its snacks and cigarettes then stare and admire the package labels with the bright oranges and mustardy yellows.

While we waited for the washer to end, we sat on the orange laundromat chairs (bolted to the ground in case anyone tried to steal them, I figured). My eyes wandered—at the graffiti, the announcements, the tile floor that needed a broom and a mop, the Spanish newspapers with the sexy ladies with their back to the readers wearing a two piece—a thong and high heels and the constant drop off and pick up of wives and daughters.

Swinging my feet back and forth out of boredom, I stared at the dryer’s circular-glass door with the thick-black trim, where garments would slowly go round and round and round and round, painting a picture of a vanilla and chocolate ice cream swirl, which was like meditating in front of a TV screen. Another dryer gave form to a motley of colors from the palette of Matisse’s bright yellows, blacks, oranges and greens Ms. Watson, my art teacher, had lectured on. And then, the dryer came to a full stop, and the colors—the burgundy red and thorny pink roses and the stoic lion—on heavy blankets took their true forms in need of folding.

Mom and Dad were always working for our dream house. In his early twenties, dressed in slacks and a tie, José Armando, our real estate agent, came to our apartment and talked to my parents about becoming homeowners. He sat patiently for what felt like hours translating endless paperwork. José Armando, Tijuana born with Sinaloa roots, grew up in Carlsbad, “Carlos Malos.” He smelled like a professional, and the heaviness of his cologne and starchy clothes filled our small kitchen and living room long after he was gone. Our real estate agent felt like familia.

“Helena and Francisco, the contract states that if you complete all the renovations within a year, the bank will approve the loan. You can move in now, but the house is not in living conditions.”

“But Jose Armando, I’m sure you’ve heard stories--what if the gringo doesn’t keep his promise?” Mom asked our real estate agent.

“Helena, please trust me. Mr. Stoddard is a good man and will not back out of the deal because he signed the contract,” José Armando assured Mom the owner would follow through. “You know Francisco more than I do. Your husband is going to make the house look like a palace—like your dream home. Helena, the property even has a water well. You can add the roses, calla lilies, and fruit trees you’re looking for in a property. And, most importantly, you won’t have to commute from Vista to San Marcos anymore.”

Where Dad and Mom came from, waiting periods to build a house didn’t exist; people didn’t need permits to build a home made from adobe or blocks. In the U.S., however, my parents had to settle for a fixer-upper Dad could mend in no time with the help of family and friends.

When José Armando finally struck a deal with the owner, it took Dad a whole year to claim the house on 368 West San Marcos Boulevard as our own. After Dad came home from working construction all day, he’d work at home. Mom must have had sleepless nights when Father agreed to buy our first house. That’s because Mother didn’t see what Father saw. We would have a street number to ourselves, 368.

The first days at 368, Mom refused to eat in the kitchen, and how could she eat in there? How could her children eat in that thing Dad called kitchen? Yes, the house included a small stove, but cockroaches were baking their own feasts in the oven. Dad imagined a swing set for Crucito in the backyard’s green lawn. But Mother had heard the neighbors walking by say the backyard turned into a swamp during the rainy seasons. Dad imagined a one-foot swallow lined with miniature plants that would keep the water moving to the large apartment complex next door. But Mom saw the swamp at our feet. Dad imagined the pantry and mom’s new wooden cupboards. But Mom saw mice and cockroaches. Lots of cockroaches. Mom saw the faded dilapidated and peeling mint green paint. Dad saw a new wooden exterior and a fresh coat of paint.

Our new but old kitchen was infested with silky brown cockroaches—the thin kind that matched the plywood. Underneath the crawl space lived the critters, and at night, big roaches squeezed and welcomed themselves in through both the front and back door to drink water and eat crumbs. Paloma and I, in our superhero capes, made from black trash bags, became Las Cucaracha Warriors de la Noche and ran after the cucaracha bandits. We routinely turned off the lights, and then at about ten o’clockish, Mom turned on the kitchen lights, and Paloma and I charged at them. While they scattered everywhere, we all took our turns killing the horde of nightly visitors. The pest problem at 368 went away with endless nights of Raid attacks and hot water splashing. Paloma and I even conquered our cockroach phobia and squished cockroaches with our very own index fingers.

The master bedroom had seven layers of dusty carpets pancaked on top of each other. The wooden floor in our living room held itself together miraculously—we were always careful to wear shoes to prevent any splinters from pricking our bare feet.

When we finally settled into our new home, one Saturday morning Paloma and I still in our pajamas were arguing over who would have to sweep and mop before our parents got home from work when suddenly we found ourselves shoving and wrestling each other. And then with a big push, the unexpected happened. I flew through the wall.

“Oh my God, Chofi! Look what you did!”

“Look what I did? You pushed me, Mensa!”

Paloma and I had to reconcile immediately to cover up the crime scene.

When Dad got home later that afternoon and walked through the hallway to inspect our chores, he demanded an explanation, “¿Y este pinche sofá? ¿Qué está haciendo aquí?” Chanfles, we thought as our eyes placed the blame on each other. Dad gave us the mean Martinez Castillo stare with the white of his eyes showing that always worked, shook his head, and stormed out of the house because Dad knew he had to replace all the house’s old plywood with new drywall.

Our idea of placing a love seat in front of the hole to cover it up didn’t work. Our fear for our father’s punishment turned into giggles and then uncontrollable laughter. Poking at each other’s ribs and yelling at each other, “It’s your fault!” and “No, it’s your fault!” we almost peed our underwear. We laughed at the hole in the wall, the sofa that barely fit in the hallway that must have looked ridiculously out of place in our father’s eyes, and at our new but old house facing the boulevard.

Strangers driving by honked or waved and gave Dad a thumbs up when he worked on our house on the weekends. We were living in Father’s dream home, and we were happy. José Armando, our real estate agent, was right—Dad fixed our house, and Mother created her garden of dreams, where Dad and Mom planted hierbas santas. Orange, avocado, peach, cherimoya, guava, and purple fig trees. And native yellow-orange, deep-purple, and rose-colored milkweeds for our butterfly relatives who passed by and travelled south to Michoacán, our parents’ homeland. One day we would follow them if Mom and Dad worked hard and saved enough money. One day.

In San Marcos, our backyard smelled like Idaho. The familiar smell of manure from the Hollandia Dairy on Mission Avenue lingered in our backyard. Months before the guava tree joined us at San Marcos Boulevard, Mom took free manure from the dairy for our garden and prepared the earth with water. Even if we already had a few trees, Dad and Mom talked about the trees and plants with special powers that would join our family. Next to the guayaba tree’s new home, the apricot tree had already joined us, and now it was the guava tree’s turn to step out of its black plastic container and to spread its roots and branches. At the end of the week with their Friday paycheck, Mom and Dad’s eyes were set on an árbol de guayaba.

Right after work Dad drove us to the northside of San Marcos on the winding road to Los Arboleros, the tree growers’ ranch on East Twin Oaks Valley Road, to buy the perfect tree for our backyard. As we approached a dirt road leading to the Santiago property, Don José in his sombrero and red and yellow Mexican bandana tied around his neck waved at us. At his side, two large Mexican wolfdogs with imposing orange eyes barked at us as we approached the nursery next to their house.

“Paloma and Chofi, be careful with Don Jose’s dogs.”

“Okay Ma,” we answered in unison.

“Buenas tardes, Francisco and Helena. Don’t worry, Señora Helena. My calupohs don’t bite unless they smell evil. They scare off the coyotes that want to get into the chicken coop. Last week a red-shouldered hawk snatched one of my María’s chickens in broad daylight.” Don José’s dogs, Yolotl and Yolotzin, sniffed our stiff bodies while I prayed to San Jorge Bendito: “San Jorge Bendito, amarra tus animalitos . . . .” Yolonzin sniffed and licked my hand. Thankfully, Don José’s calupohs remembered us; we were in the clear. “If you need anything, holler at me. I’m going to water the foxtail palm trees on the other side.”

At Don José and Doña María de la Luz Santiago’s small ranch, Paloma and I were careful not to step on rattlesnakes. We walked through the rows of small trees in 15″ containers and played with sticks next to a large flat boulder with smooth holes. I filled the holes with dead leaves and dirt and mixed it with a stick. “Paloma, let’s ask Don Jose about the holes on this large boulder. How do you think these holes got here?” Paloma shrugged her shoulders and signaled with her head to get back. With the calupohs following us, we found Mom and Dad still deciding on a tree and a crimson red climbing rose bush.

“But Pancho, look how green the leaves look on this one!”

“Yes, Helena, but look at this one. It has a strong tree trunk.”

“Pancho, this one has ripe fruit! Smell it, Pancho. With time, this one will be strong too.”

“You’re right, Helena. We can take the one you want. Let’s pay Don Jose and get going before it gets too dark, so we can plant our tree today.”

“Yes, Pancho, it’s a full moon!”

“Paloma and Chofi, I’m glad you’re both back. Go look for Don Jose, and tell him we’re ready to pay.”

Paloma and I ran to look for Don José. On our way to find him, I remembered we needed to ask him about the holes on the boulder.

“Hola Don Jose. My mom and dad are ready to pay.”

“Let’s go then.”

“Don Jose, we have a question for you. We saw a big flat rock on your property, and we’re wondering how the holes got there.”

Don José cleaned his sweat with his bandana and gave us a pensive look.

“Those holes. Well, Chofi, as you may know, this land you see here from Oceanside all the way to Palomar Mountain and beyond was inhabited by Native people. Women sat and pounded acorns on metates like the one you saw and made soup and other foods. You can only imagine how many years it took for those indentations to leave their mark and to withstand time. Those women, Chofi and Paloma, left their mark.”

“Oh, wow, Don Jose. That’s why the road is called Twin Oaks Valley Road? It’s a reference to Native people’s trees, who lived in this area?”

“Yes, Chofi and Paloma. Native people still live on these lands—in Escondido, San Marcos, Valley Center, Fallbrook, Pala, and Pauma Valley and beyond. Ask your U.S. history teacher about the people who inhabited these lands. I’m sure they can tell you more.”

“Thank you, Don Jose. I’ll ask.”

Dad and Mom paid Don José, and off we went to plant our guayaba tree. With our guava tree sticking out of the window in the Monte Carlo and lying on Paloma, Crucito, and me in the back seat, Mom was all smiles and kept glancing back.

“Pancho, please drive slowly and turn on your emergency lights. Children, hold onto our tree carefully.”

“Don’t worry Helena. Two more stop lights, and we’re almost home.”

Dad agreed to Mom’s pick because he knew she loved guayabas—all kinds. This time they chose the one with the two guayabas with pink insides, which wasn’t too sweet and just about my height. I preferred the bigger trees at Los Arboleros. Why couldn’t we get bigger trees? Mom and Dad always chose the smaller trees because those were the ones we could afford, and plus we didn’t have a truck like our neighbor Don Cipriano’s, but maybe we could borrow it next time.

As soon as we arrived home, Dad cut the container down the middle with a switchblade, and Mom pushed the shovel down with her right foot and split the earth.

“¡Ay, ay! ¡Ay Pancho! Be careful with the tree’s roots. Here, grab the shovel. Let me hold onto the arbolito.”

Dad dug the hole, exposing the dark brown of the earth as two pink worms shied away from the light.

“Dad, can Crucito and me get the worms, pleaseee?”

“Hurry up Chofi and Cruz. Go ahead. Your mom and I want to plant the tree today.”

“Okay, Apá!”

While I carefully took the worms from their home, Mom held the guava tree as if she held a wounded soldier and whispered to the tree, “Arbolito, don’t worry. You’re going to be safe here. I’m going to water you when you get thirsty and take care of you—we all will.”

“Pancho, one day we’re going to make agua de guayaba.”

“Sí, Helena, we’re going to make guayabate like the one my mom used to make. It was so good!”

“I bet it was, Pancho. To prevent a bad cough, my mom used to give us guava tea to fight off the flu.”

“Helena, did you know guava leaves are also good for hangovers?”

“Ay Pancho. ¿Qué cosas dices? Let’s get this tree planted.”

From the dried-up manure pile, Dad mixed the native soil and compost and pulled the weeds. As Mom placed the rootball above the hole, they both looked for the guava tree’s face and centered the tree on top of the hole. With the shovel, Dad poured the dirt around the tree. Mom took the shovel from Dad and pounded softly on the dirt surrounding the guava tree, making sure they left the edge below the surface.

Next to the apricot tree with a woody surface, the small guava tree with tough dark green leaves would be heavy with fruit one day for our family, our neighbors, and friends. Dad went looking for a canopy for the young guava tree to protect her from winter’s threatening frostbite, and mom stood in the garden, admiring our new family member.

It was time to return the worms to the earth; they were so tender but so strong. I made a little hole with my hand, placed the worms inside, said thank you to the worms, and covered them with dirt. The guayaba tree would make a perfect home.

A chapter from the upcoming book

Three Batos And One Chavala

by Tommy Villalobos

“I’d like to give you a quick background of my story. It’s a novel, or novella, called Three Batos And One Chavala. It’s about a train trip from L.A. to San Francisco set in the 1930’s. I did research for that time period, including trains, terminology, dress, music, locations and geography. Three guys (los batos) compete for one Chicana beauty (the chavala) on the train ride. The story starts out in the East L.A. of that period and ends up in San Fran and Watsonville, with side trips back to L.A.. There’s a dominant tía involved, protectress of the girl, Samuela, who tries to trip up all suitors of her sobrina.”

“Señora, llegó otro.”

“This is outrageous!” wailed Sandra. “Hope you told him to go find another house.”

“No, también lo tire en la sala.”

“Is he a poetry critic from a magazine?”

“Not even close, Señora. He has shiny shoes, suit, tie and slick-back hair. He says his name is Alberto Pistillo.”

“¿Alberto Pistillo?”

“Yes. He showed me something with his name, I guess, but I couldn’t read it since I left my lentes in the kitchen where I was cleaning the frijoles.”

Sandra walked to the door with the ugliest face she could imagine making, stopping at a wall mirror to look at herself. Satisfied, she continued on. Like she had just announced, this was outrageous to her. She recalled this apestoso, Alberto Pistillo. He was the hijo of Fred Pistillo, the one who was helping Joe Milago in trying to snag her little house overlooking the Pacific. He lived somewhere around here. This unwelcome visit could only have one purpose and that would be to talk about her house. She headed toward the living room determined to stomp out the Pistillo familia from her life once and for all.

Alberto Pistillo was skinny, appearing hungry for both food and love. He had dark, beady eyes and a pug nose, giving him the appearance of a desperate Pug Dog. In fact, he looked more like a Pug Dog than a Pug Dog did. He shocked diners in restaurants when he sat eating spaghetti and cream carrots. It seemed to them that he would prefer a small steak bone chased with a dog biscuit.

“Buenas días, Señora Westo.”

“Sit,” she said, keeping with the Pug theme.

Alberto sat even though he looked as if he would rather be petted. His beady eyes scanned the room, a wry smile on his mug, if I can use that word given his canine appearance.

“Señora, I need to talk with you alone.”

“You are talking to me,” said Sandra, waving around the room. “And as you can see, we are alone.”

“Where do I start?”

“I’ll tell you. No. The answer is No.”

Alberto shook visibly.

“Then you know?”

“That is all I know since I ran into Mr. Milago. He can talk about nothing but my humble casita. Your father talks about nothing else. And now,” Sandra raised the volume several decibels, “you show up to hammer my head some more. One more time, nothing doing. There isn’t enough money in circulation to let someone live in my home by the sea.”

“Then you don’t know why I am here?”

“You didn’t come to talk about my casita by el mar?”

“No, I didn’t come about that.”

“¿Entonces, por que diantre estás aquí?”

Alberto shifted his feet nervously. He moved his body as if were trying to get out of it.

“I like to mind my own business.”

He paused.

“Really?” she said, to get him started again.

Alberto restarted.

“I don’t carry chismes with just anyone.”

“I’m honored.”

“I don’t make…”

Sandra was never a patient person. Or poet.

“Just let us accept all your character traits, and let us take it from there,” she said bluntly. “I am dead sure there are all kinds of things you don’t do. Let’s talk about what you can do about where you are now. What do you want to talk about, if I can make such a shocking demand upon you?”

“The marriage.”

“Marriage?”

“Your niece’s marriage.”

“My sobrina is not married.”

“No, but she is going to be. At The Little Chapel of Hope in Gardena.”

Sandra gawked.

”¿Éstas loco?”

“I’m not happy either,” said Alberto. “I’ll tell you, and speaking for myself, I’m in love with her, too.”

“Nonsense as far as you’re concerned. But who is this other drip?”

“Felt that way for years. I’m one of those silent types, hiding in the shadows, liking a woman but never telling her or showing her my feelings…”

“Who is the snake who has ambushed my sobrina?”

“I have always been a man to…”

“Mr. Pistillo! Let’s also assume you have some good qualities. Tell you what, let’s not even talk about you anymore. You barge in here with a crazy story…”

“Not crazy. Facts. I heard it from a primo, who heard it from a prima, who heard it from an abuela, who heard it…”

“Will you tell me who the alley cat is who has tricked my niece or do I choke it out of you?”

“I agree that she is muddled, alright,” said Alberto, jumping at the opportunity to be agreeable, “and I think she should be marrying me. She is a fine catch. We practically grew up together and I loved her then and love her now. I’m sure she knows. But things sometimes don’t go the way you want them to. I saw a chance last summer but I lost my nerve. I am not a smooth and flashy man with a great line. I can’t…”

“Stop now!” said Sandra. “Hold your self-analysis for friends and family who would be somewhat interested. I want to hear the name of the worm my niece is NOT going to marry.”

“I thought I told you,” said Alberto, surprised. “Extraño. Guess I haven’t! Funny how you feel you’ve said something and haven’t. People know me as…”

“Whatever is the fool’s name?”

“Milago.”

“Milago? Trimino Milago? The wild-haired son of Joe Milago I met at your father’s casa?”

“You have it. What a guess. You should stop it before it happens.”

“Watch me.”

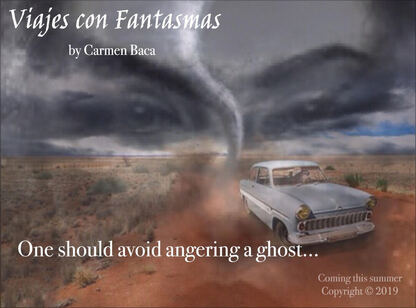

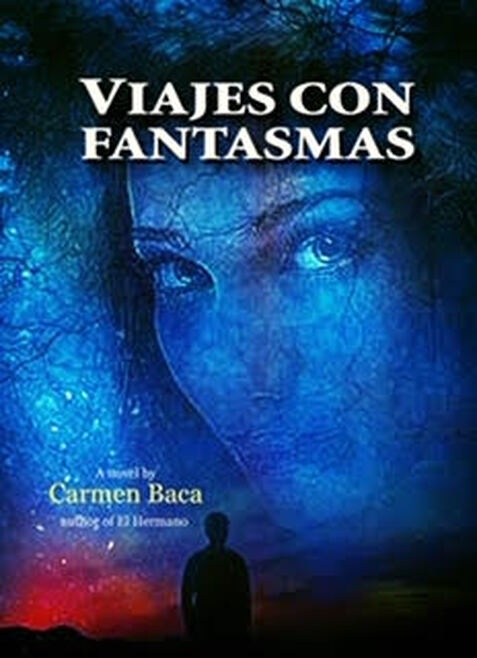

"Recuerda"

from Viajes con Fantasmas

Somewhere in the void of nothingness where la Llorona had been keeping herself in secluded oblivion for the past decade, there was a spark of something. Almost as if the small ember beneath the kindling set to light the morning fire came to life with the breath of a breeze, something in the old ghost’s mind ignited and came alive once again. She couldn’t quite grasp what it was that sparked her to consciousness, but she knew it could only be one thing: Rosita or someone she loved was approaching the boundaries which kept her restrained to the southwest.

As the Tapias had made their home so far away from anything they ever knew and tried consciously not to think of the ghost who was the cause of their move, she lay dormant. Not moving, barely existing, but thinking, always thinking of her revenge and plotting different means to accomplish it when the time was right. She relied on the patience she'd developed over the 148 years of her eternal life.

From time to time, her own son came into her mind and had she been able to cry tears, she would have flooded her location with years of sobs. Instead, she tried minute after minute, hour after hour, and day upon day to reach the Tapia family with her thoughts. Searching everywhere for the boy who escaped her clutches and whom she longed to capture and never release, she did not give up her quest, even though she knew her boundaries limited her reach. In Rosita's old neighborhood, there was a house which held promise. There lived a young woman about the same age as Christino, and like clockwork every Sunday evening she sensed a connection between this girl and the young man though she could also tell there was some distance between the two. She felt that using this girl would enable her to get closer to her goal, and she bided her time until this something or someone crossed the southwest boundaries and fell into her hands. That's how relentless she was and how ruthless.

So, while one part of her mind acted like the ever-undulating snakes sprouting from the head of Medusa constantly using their forked tongues to feel for her prey, she used another part to entertain herself with the memories of contented times to pass her period of isolation. Of course, her chief enjoyment was recollecting all the instances she had encountered humans.

She recalled an occasion where she had just bitten into a succulent wild strawberry she found in an orchard when she spotted a trio of adolescent boys walking past. Sure they were up to no good—apple stealing, most likely—she moved to stand before them when they paused under the first large tree with fruit-laden branches which almost touched the ground.

Before they could move, she blew a strawberry-scented breath into their faces, first left to right and then back again, watching as their eyes opened wide and their mouths too in preparation to speak.

"What the…"

"Did you feel that—"

"Oh, Shi—"

Thoughts did not quite make the exclamations complete so quickly did they take steps back. Each turned in all directions to figure out what it was.

"There's no wind," reasoned one.

Another, who began shuffling a foot through the fallen leaves and underbrush and looking at the growth, chimed in, "I don't see a single strawberry."

Then the last said what they had all been hoping none would voice: "La Llorona—it had to be!"

As if to prove him right, an apple fell from the tree they stood beneath and hovered before them in the air as though suspended from invisible string. María had it from the stem and allowed it to swing toward the boy who had said her ill-gotten name. Then the ghost let it loose where it struck him smack in the center of his chest. She didn't throw it hard; it barely hit with a small thump, but he fell back in a faint.

"Oh, my God! He's dead!"

"Quick, grab his arm!"

The other two took an arm and dragged the boy backward as fast as they could get away with tree limbs and shrubs in their path. No matter—though the boy's head got stuck in a large weed once and bumped into a small log on their way out of the arbolera, the three kept going until she could see them no longer.

The memory triggered more, and María retained her position where she lay, knowing the end to her self-imposed banishment was near. She need not waste what time she had to remain dormant in guessing what was to come.

So, as the two travelers made their way down the Alaskan coast toward Washington, still far from their destination, the evil phantasm the older one wanted to avoid and the younger one knew nothing about kept her senses aware. With each mile that passed, she kept her patient vigil.

The days of travel passed routinely for Thomas and Tino; as the number of miles beneath the car's tires grew, so did Tino's impatience to get to their final destination. The earthquake of 1964—ten years before—when he'd been five-years-old, bothered him. Sometimes, when any significant alteration of his daily routine occurred, he became so anxious that Rosita had to teach him how to ward off panic attacks and accept what he couldn't change. Marisol's leaving was an especially trying time for the boy, but the weekly phone calls and letters between the two kept him from experiencing too much anxiety.

Rosita hoped the intervening years between Marisol's departure and Tino's reaching his eighteenth year would make him more amenable to change, and she worried about his leaving to college at all if he weren't able to adapt. But then Marisol's mysterious illness arose, and the defect in his character seemed to disappear from the moment he heard her mother's tearful voice say, "Oh, hito, I think our Mari's dying." Concern for the love of his life had done what nothing else, not even subsequent earthquakes brought by Mother Nature herself, could have made him do in all his formative years—accept change and move forward with it, rather than pretend it wasn't happening or worry himself sick over it. He had a quest at last, and a journey ahead that would prove his mettle. Like Odysseus, Tino would face dangers he didn't expect. Unlike the epic hero though, Tino had no idea.

So Thomas and Tino traveled through Washington, the top right corner of Oregon, and the bottom left corner of Idaho without incident and made good time. Thomas gave the wheel over to Tino on the long, flat stretches of highway so he could rest his eyes to make the best time of the almost twenty-three-hour trip. Thomas needed no sleep, no resting of any body part, but he had to convince others he was human. And so he did human things he remembered but had no need for any longer.

When they reached Utah, something happened which made Thomas well-aware they had reached the southwest. As he drove down the highway, Thomas began getting the feeling he always did when he sensed danger. He glanced at his passenger and saw Tino was awake, so he asked him to keep an eye out.

"For?"

"I don't know, but something feels off, like maybe a thunderstorm is coming."

"I don't see—" Tino began, and left his statement unfinished when he saw it. A sudden dust devil appeared to their right off in the distance, which was strange because Utah isn't known for tornados. Tino called attention to it, but Thomas had already seen it and was debating either accelerating or decelerating to avoid it since it looked to be coming right for the road they were on.

"What the heck—" Tino began when it shifted course and seemed to head right at them. It seemed Mother Nature wasn't finished teaching Tino lessons.

"Hang on!" Thomas did speed up then, the car shaking and rattling as it shot over eighty miles per hour and the dust devil spun itself into a full-blown tornado. Rocks, gravel, brush, small branches, tumbleweeds, and who knew what else slammed into the vehicle on all sides as Thomas fought with the steering wheel which was shaking so badly Tino feared it would fly right out of his friend's fists. And just as fast as the twister hit, it blew itself out with a giant puff of dirt and dust behind them.

Thomas looked at Tino; Tino looked right back.

"Did you see that? What was that? Why did—"

Thomas held up a hand as he began slowing the car to its normal pace but kept going. "I'm not sure why it happened just as we passed, but that twister must've caught a nice updraft to form as fast as it did," he offered a half-educated opinion and hoped he'd halted Tino's questions. He knew the young man was ignorant about his mother's plight with la Llorona, and he didn't think it was his place to set him straight. And though he didn't like not being truthful with Tino, he didn't know what else to do. Surely, he needed to have a conversation with Doña Sebastiana after all. After another period of travel, they reached a small town. Here was as good as anywhere, Thomas thought, to have supper and a short rest before continuing on.

So the two stopped at a quaint diner with '50s memorabilia, and Thomas waited for the inevitable questions Tino was bound to have. The younger man surprised him, however, and spent the time waiting for their order by strolling along the walls featuring old black and white photographs of '50s stars and plugging quarters into the jukebox. When their food arrived, they ate as though they hadn't eaten in days and sat back when they finished, sated and lazy with the fullness of their stomachs. They didn't waste time, both anxious to get going again and left shortly thereafter.

Before long, they crossed into the southwest corner of Colorado, and again, Thomas listened to his inner voice warning him of impending danger. Again, he asked Tino to keep vigilant.

"Not again," he groaned, sitting up in his seat and sweeping his gaze from one end of the windshield to the other. Turning in his seat to look behind, he saw nothing amiss in any direction. He should've looked up. Everything happened simultaneously—just as they were passing an especially high cliff to their left with a precipitous drop to a canyon on the right, Thomas' acute intuition kicked in, and both he and Tino heard a rumbling from above. The older man floored the accelerator at the same time a boulder larger than the car crashed onto the highway behind them.

Slamming on the brakes, Thomas jumped out of the car on his side, and Tino did the same on the other.

"Did you know that was going to happen?" He looked wide-eyed at his mentor. Then he accused, "You knew that was going to happen. How, why—"

"I heard the rumble before you did, I guess," Thomas interrupted. "I've always had exceptional hearing," he added as both looked back at the cars that were lining up one behind the other due to the obstacle in their way. "At least we're not trapped on the wrong side of that rock." He got back into the car, and Tino followed suit. When Thomas offered no more explanation, Tino remained quiet, vigilant eyes looking in all directions. As he drove, Thomas' thoughts took him back to the twister in Utah and the landslide in Colorado. He had a feeling in his gut the incidents had been orchestrated, not accidental. There was something more at play here, and he wondered if he should let Doña Sebastiana know. Then again, the ancient one knew almost everything, so he determined to be extra alert and keep his concern at bay unless more happened to cause concern.

From mountain ranges in the north and south-central portions, to desert like sections in the southwest, central and south eastern parts, with gorges and rock formations, cliff dwellings and caverns, the state had much to offer its residents and tourists alike. So many who ventured into the enchanted part of the southwestern United States fell in love with the varied landscapes and left their homes elsewhere for the fresh air and mystic mystery of the place. It was no wonder la Llorona and so many others of her ilk refused to leave it even when they passed. Haunting their favorite places, from hotels to individual houses, cemeteries, and churches, bars and brothels alike, like Billy the Kid in Fort Sumner, an unknown woman in white by the highway around Santa Rosa, and even a little boy haunting the Kimo Theatre in Albuquerque. New Mexico has always been a safe haven for ghosts. And they were spotted regularly enough that everyone believed in all of them.

The legend of la Llorona was, by far, the most widely known, however. She was the only one who had been spotted through the recent centuries in all of the south west states. Others, like el serpiente, were seen in specific locations. There were still others who were spotted in many places, but they seemed to be ghosts of different people. It was la Llorona, the Weeping Woman, who was spotted throughout the decades searching for her lost children as she wandered along both lush and nearly barren river banks from Utah, to California, to Mexico and the states between.

Just as Thomas approached the border at the top corner of the state, his intuition kicked in, stronger than at any time since his demise on the train collision. It was a punch to his mid-section that left him bent in pain as the hand not on the wheel pressed hard against his stomach. He inhaled with the intensity of the blow and sat up straight so fast his spine gave a crack.

And it was gone.

The moment the car flew past the state line dividing Colorado from New Mexico, he felt exhilarated—still concerned, wary, but not fearful—gee, had it been fear—he wondered, interrupting his own thoughts.

He shook his head and rubbed his eyes, alert like a watchdog to danger he senses in each bristle of hair on his spine, but not yet having caught the scent sufficiently to know what or where it was. Thomas opened his mouth to tell Tino once again to watch out for something, but there was a whoosh to his right—a blast of light from the window next to Tino as though something like a fireball had been flung from the sky into the forest with great strength.

"Ahhh!" The two pitches of baritone from older and younger man simultaneously would’ve been funny, especially when they turned to look into each other’s wide eyes before turning again to the woods. But what they saw was far from humorous.

Thomas floored the gas pedal for the third time and caused Tino to clutch what he could find to hold on. The trees caught fire, and within seconds the flames raced toward them.

Tongues of red, orange, yellow, and even white flames fluttered and reached for them.

When the car shot forward, so did the fire. It was as though a giant had blown a big breath toward them right from the spot of the initial explosion. The danger was immediate; Thomas felt the heat of the flames as they shot over the roof of the car before it accelerated. When Tino, crouching still in the passenger seat, looked into the door mirror, he could swear the flames formed a giant face—the face of a woman who seemed to be crying fire. He rubbed his eyes with both fists, blinked several times, and looked again. The flames were gone; there was no fire. Only a plume of black smoke rose into the sky like a finger pointing ever upward. And as it rose higher, the black turned gray, then white, and then dissipated into the air into nothing. The forest was intact, the trees as green as they always were.

"I did not imagine that." Tino’s voice started with a quaver and finished with certainty. "What innocent explanation are you going to try to cover this disaster up with? At least with the avalanche you didn’t even try to explain, but with that tornado—when you tried to make light of it—nuh huh, no, no way. I need the truth, Thomas. Don’t try to pacify me anymore. There’s something up—something that’s been going on for a while, I can tell. I just don’t know what it is or why it seems to target us. This has to do with my parents' refusal to come back to New Mexico, doesn't it?"

Within a few hours, Thomas knew they’d reach their destination. He hadn’t changed his mind. He was not the one to tell the boy the truth.

"You need to go to sleep, son."

"Whaaa—"

"Hear me out." The hand he held up caused Tino to shut his mouth.

"Because of what you’ve witnessed on this trip, you should trust what I’m about to tell you will work, and do as I say. The answers you seek will come to you in sleep. Only in a deep, genuine sleep. So force yourself to relax with the sound of the road beneath the tires and the silence of the air around you. Sleep."

He said no more, and Tino didn’t ask for more. Just as he had stopped asking questions about the matter through the years because his parents always refused to answer, he knew he had to stop now and do as his older friend said. He gave himself a shake, loosening his limbs from tense to relaxed, leaned back against his seat, and crossed his arms over his chest. With a deep sigh, he closed his eyes and gave sleep his best effort. For a few miles, nothing happened. His mind swirled with questions and answers he guessed at, and he didn’t think he could stand a moment longer trying to quiet his thoughts. And that was when sleep came and drove his consciousness down into blackness, nothingness, and left his mind open and malleable to the entrance of the ancient ghost’s thoughts.

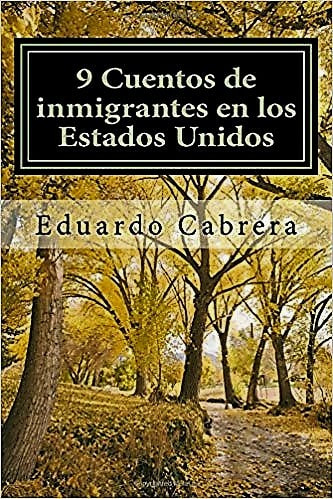

Encontrar una voz en espanglish

Un extracto de 9 Cuentos de inmigrantes en los Estados Unidos, una colección de cuentos

por Eduardo Cabrera

Espanglish

Un día cualquiera en la rutinaria vida de la familia de Ernesto, su padre llegó a casa con una novedad que les cayó a todos como un balde de agua helada: tenían que mudarse a otro estado. Debido a la gran crisis económica por la que atravesaba el país, a Máximo, el padre de Ernesto, le habían ordenado trasladarse a Los Ángeles. Las grandes empresas estaban eliminando muchas posiciones, cerrando filiales, y trasladando la mayoría de sus trabajos a México y a otras ciudades de los Estados Unidos. Se trataba de corporaciones a las que no les interesaba la pérdida de fuentes de trabajo para el país ni los efectos negativos en la sociedad. Su único objetivo era incrementar sus ganancias económicas.

Ernesto y su familia vivieron la mudanza a Los Ángeles con una mezcla de fuertes sentimientos positivos y negativos. Por un lado, lo más importante era que Máximo había logrado mantener su trabajo, lo cual era, dadas las circunstancias, por demás significativo. Muchos de sus compañeros habían perdido sus trabajos y habían quedado literalmente en la calle. Pero por otra parte la mudanza significaba la pérdida de algunas amistades y tener que adaptarse al ritmo de vida de una gran ciudad y de la región del sur de California. Sin embargo, para Ernesto y sus dos hermanos el cambio de ciudad era un rotundo motivo de celebración. Sus padres no comprendieron la reacción tan positiva, pues pensaban que estarían más apegados a sus compañeros de escuela y a sus amigos del barrio. Ernesto, el mayor de los hijos, les aclaró a sus padres que el motivo principal de tanta alegría era el hecho de que pensaba que en Los Ángeles tendrían muchas más posibilidades de desarrollarse como músicos. Luis y Felipe habían seguido los pasos de su hermano mayor en cuanto a la dedicación a la música. Además, tal vez en la nueva escuela les darían la oportunidad de formar parte de una banda o de una orquesta.

La mudanza se llevó a cabo durante las vacaciones de verano. Los muchachos estaban ansiosos por comenzar el ciclo escolar y conocer a sus nuevos compañeros. Entre ellos habían estado comentando lo bueno que sería asistir a una escuela con muchos estudiantes latinos como ellos. Ya no serían los “raros” de la escuela, sino que serían como la mayoría. ¡Qué alegría tan grande estar rodeado de chicos como ellos! Para las vacaciones Máximo planeó una serie de actividades destinadas a posibilitar la mejor adaptación de su familia al nuevo lugar en que les había tocado vivir. Como la familia de Ernesto practicaba la religión católica, Máximo decidió averiguar cuál era la iglesia más cercana a su nueva casa. La suerte estaba de su parte, pues encontró una iglesia a solo 3 cuadras. Ya frente a la iglesia Máximo trató de calmar los nervios que le producía la nueva situación, respiró profundamente, y se encaminó a la puerta principal. Para su sorpresa, la puerta estaba cerrada con llave, algo que no se acostumbraba a hacer en su pueblo. No podía irse de ahí sin ninguna información, pues deseaba contarle a Gertrudis, su esposa, algo que pudiera alegrarla. Máximo se sentía culpable por la repentina mudanza, y quería hacer todo lo posible para complacer a su familia. El bienestar y la felicidad de todos dependían de él. Luego de pensar durante algunos minutos que le parecieron eternos, Máximo decidió golpear la enorme e imponente puerta de la iglesia. Una mujer de unos sesenta años abrió toscamente la puerta y, con cara de pocos amigos, lo recibió con un monosílabo: “¿Si?”

Máximo sintió que todo el cuerpo se le había congelado. Fue como si le hubieran echado encima un balde de agua fría. Con voz temblorosa le explicó a la poco amable señora que él y su familia se acababan de mudar, y que lo primero que hizo fue buscar una iglesia.

-La iglesia está cerrada –contestó la mujer al mismo tiempo que cerraba la puerta apresuradamente. Una inmensa tristeza invadió el alma del pobre hombre. Inmediatamente pensó que no podía decirles a su esposa e hijos lo que acababa de suceder. No quería causarles semejante desilusión. Decidió entonces averiguar el horario de la misa dominical de alguna otra iglesia católica. El encargado de la casa que alquilaba le informó a Máximo que había una misa el domingo a las once de la mañana en una iglesia que quedaba a una milla de ahí. Inmediatamente compartió las buenas noticias con su familia; todos estuvieron de acuerdo en asistir a misa el primer domingo en su nueva ciudad. Sería una gran oportunidad para comenzar a establecerse en la nueva comunidad y de hacer nuevos amigos. Ernesto y sus hermanos no estaban muy entusiasmados con la idea de practicar una religión, pero había una compensación: la posibilidad de tocar algún instrumento durante la misa en la banda musical de la iglesia.

Por fin llegó aquel domingo tan especial. Para esa primera misa en Los Ángeles, Ernesto se puso un hermoso smoking que su madre le había comprado en una tienda de objetos de segunda. Sus hermanos fueron prolijamente vestidos con saco azul y corbata. La misa fue completamente en español; Máximo y su esposa no tuvieron ninguna dificultad en comprender la palabra sagrada ni el sermón del sacerdote. Pero sus hijos, que no estaban acostumbrados a escuchar hablar en español durante tanto tiempo, no entendieron casi nada. El coro de la iglesia cantaba de forma bastante entonada; pero la banda de músicos, a juicio de Ernesto, desafinaba de una manera atroz. A pesar de lo mucho que tuvo que sufrir al escuchar a tan malos músicos, Ernesto sintió un dejo de esperanza, pues aumentaban las posibilidades de que él y sus hermanos fueran aceptados en la banda.

Al finalizar la misa, Gertrudis, la orgullosa madre, saludó al sacerdote y apresuradamente se acercó al director de la banda musical. Luego de felicitarlo, le habló sobre los antecedentes musicales de sus hijos y le preguntó sobre la posibilidad de que ellos integraran su banda. Mr. Pérez, director de la banda, le dijo que los dos menores eran demasiado chicos, y que a Ernesto podría darle la oportunidad si estuviera dispuesto a asistir a todos los ensayos que se realizaban a diario a partir de las 8 de la noche. Gertrudis le respondió que tendría que consultarlo con su esposo, y que le respondería la semana próxima.

La discusión en que todos los miembros de la familia participaron giró en torno a la participación de Ernesto en la banda musical de la iglesia. A la tristeza de Luis y Felipe por no poder participar, se sumaba la negativa de Máximo a que Ernesto formara parte de la banda. Según el padre, ensayar durante todas las noches afectaría el rendimiento académico de Ernesto. Además, consideraba que era demasiado exigente, y exagerado, pretender que se ensaye todos los días para una banda musical de una iglesia. Gertrudis luchó con todas las armas disponibles en defensa de Ernesto, hablando de sus sueños como músico, su futuro, y su gran dedicación durante tantos años. Y no dudó en echarle en cara a Máximo su responsabilidad y hasta su culpa por haberse mudado. El pobre hombre, agobiado por tantos ataques de parte de todos los miembros de su familia, no tuvo más remedio que acceder a ese pedido, aunque lo consideraba absurdo.

La segunda misa dominical a la que la familia de Ernesto asistió, les pareció eterna, no ya por la dificultad del idioma sino por la ansiedad por volver a hablar con el director de la banda. Gertrudis y Ernesto se movieron lentamente a través de la iglesia, dando tiempo a que los músicos de la banda guardaran sus instrumentos y comenzaran a abandonar el lugar. Ya frente a Mr. Pérez, Gertrudis le presentó a Ernesto y le transmitió la decisión positiva de la familia. El director, manifiestamente perturbado, le respondió:

-Su hijo no asistió a ningún ensayo durante toda la semana.

Gertrudis, muy sorprendida, le recordó que el domingo anterior habían acordado que ella hablaría con su esposo y que recién entonces le diría la decisión de permitirle o no a Ernesto formar parte de la banda. Mr. Pérez, de manera condescendiente, reconoció tal acuerdo, y le dijo que tendría que hablar a solas con Ernesto. Gertrudis los dejó conversando y esperó con el resto de su familia afuera de la iglesia.

Habría pasado escasamente unos quince minutos, cuando Mr. Pérez y Ernesto se encaminaron rápidamente hacia la salida y se reencontraron con Gertrudis. El serio director, ignorando a los otros miembros de la familia, se dirigió a la ansiosa madre con unas escasas pero rotundas palabras:

-Hay un problemita con su hijo, señora. Su español no es muy bueno. Acá todos los miembros de la banda, además de tocar un instrumento, cantan. Y su hijo tiene un acento demasiado fuerte.

Gertrudis, al borde del llanto, trató de contrarrestar esos argumentos que consideraba ridículos. Pensó en recordarle los estudios musicales de Ernesto, su oído absoluto, su experiencia, y hasta pensó en hablarle de racismo y discriminación. Pero se sintió mareada, creyó que su garganta se le cerraba, y que estaba a punto de desmayarse. Cuando estuvo a punto de iniciar la batalla, el director la frenó con un duro ademán y agregó:

-Lo siento mucho. Queremos incorporar nuevos músicos, pero tienen que estar preparados y disponibles para los ensayos. Si todavía le interesa, vuelva a hablarme el año que viene.

Máximo, que se había mantenido todo ese tiempo callado, alzó su voz:

-Un momento. Quiero hablar con usted sobre esta situación.

-Lo siento –dijo Mr. Pérez - se me ha hecho tarde y mi esposa me está esperando para almorzar.

Los últimos días de vacaciones transcurrieron sin mayores novedades, simplemente tratando de conocer el nuevo barrio y su gente. Los muchachos pasaban las mañanas viendo televisión, y durante las tardes jugaban a la pelota en el jardín de su casa.

El primer día de clase pasó más lentamente para los padres que para los muchachos, pues aquellos estaban ansiosos por saber cómo había sido la experiencia de cada uno de sus hijos. El primero en contar cómo le había ido fue Felipe, el menor. Con llantos en los ojos dijo que, si bien había entendido todo el material estudiado en sus clases, no le había ido tan bien en los recreos.

-¿Cómo en los recreos? –Se apuró en preguntar Máximo.

-Primero, nadie quiso sentarse a almorzar conmigo durante la hora del lunch. Y luego, en los recreos, nadie quiso conversar ni jugar conmigo. Ni siquiera se me acercaban.

Gertrudis quiso minimizar la engorrosa situación que había experimentado su hijo:

-Bueno, Felipe, seguramente tus compañeros se conocen desde años anteriores. Tienes que tener paciencia. Ustedes son nuevos en esa escuela. Ya verás cómo poco a poco te van a ir hablando y muchos van a querer jugar contigo.

Luis, que estaba ansioso por hacer su propio reporte, interrumpió a su madre:

-A mí no me gusta esta escuela. Quiero que nos volvamos a Illinois.

Máximo lo miró con una expresión adusta, como exigiendo más explicación. Luis comprendió el mensaje y agregó:

-¡Un chico me llamó Mexican! Y por más que le repetí mil veces que yo no soy mexicano, que yo nací en Illinois, me seguía diciendo Mexican, Mexican.

Gertrudis volvió a intervenir pidiéndoles que se calmaran, que mañana todo iría mucho mejor. Y que no quería volver a escuchar que nadie se quiere regresar a Illinois. Que ya eran suficientemente grandes como para comprender que tenían que vivir donde su padre tuviera trabajo. Que hay momentos en la vida que uno debe tomar decisiones que, aunque no le gusten, son necesarias para el bienestar de la familia.

-Entonces –se apresuró a decir Luis- mañana quiero llevar mi partida de nacimiento. Tengo que demostrarles a mis compañeros que no soy mexicano, que yo nací en Illinois.

Máximo le dijo que no habría ningún problema con eso, e inmediatamente le pidió a Ernesto que cuente su experiencia. El hijo mayor, supuestamente, podría establecer un tono más maduro en la conversación familiar. Sin embargo, Ernesto también había tenido su propio problema: durante los recreos todos sus compañeros hablaban en español; él no hablaba tan fluidamente en esa lengua y, por lo tanto, no se sentía tan confiado en su poder de comunicación. Incluso un compañero se burló de su marcado acento.

Nuevamente Gertrudis fue la encargada de minimizar la situación:

-De ahora en más todos vamos a ver programas de televisión en español.

En ese momento la queja se volvió generalizada entre los tres hijos. Ya no solo tendrían que sufrir en la escuela sino también en su propia casa.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Era un día tan soleado, como nunca antes Ernesto había visto en su vida. Tal vez por eso tuvo la sensación de que algo extraño habría de pasar. Fue precisamente ese día que una nueva estudiante llegó a la escuela. Su nombre era Leticia; acababa de llegar de Texas. La maestra les había anticipado el día anterior que llegaría una alumna nueva, y que todos tenían que darle la bienvenida y hacerla sentir bien. Ernesto fue el primero en hablarle. Como no sabía si debía hablarle en inglés o en español, sin pensarlo, mezcló los dos idiomas de tal manera que él mismo se sorprendió:

-Welcome to tu nueva escuela –le dijo nerviosamente.

La muchacha, sorprendida, le agradeció la bienvenida y le correspondió el gesto con una generosa sonrisa que resaltaba sus grandes ojos verdes. No intercambiaron muchas más palabras, sin embargo pasaron toda la jornada escolar juntos. Con el correr del tiempo Ernesto comprendería que aquella construcción lingüística que había emitido de manera completamente accidental, constituiría el elemento con el cual Leticia se había identificado; los latinos del pueblo texano del que ella provenía, hablaban en espanglish, tanto a nivel privado como también en público. Ernesto nunca se había imaginado que tal forma de comunicación sería legitimada por la sociedad. Sus padres siempre le habían dicho que debía hablar correctamente, lo cual implicaba hacerlo en español o en inglés, pero nunca mezclando las dos lenguas.

En casa, la comunicación entre los miembros de la familia se vio dificultada al tratar de aplicar la regla de que el idioma de uso en el espacio común debía ser solo el español. A pesar de las continuadas quejas de los tres muchachos, no tuvieron más remedio que adaptarse a la cultura impuesta por los padres. Sin embargo, a Ernesto se lo podía ver siempre con buen humor, algo que les llamó la atención a todos en su hogar. Una de las cosas más llamativas era que, cuando estaban los tres hermanos juntos, Ernesto ya no hablaba solo en inglés como lo hacía en el pasado. Paulatinamente fue incorporando un léxico no solo más amplio en la lengua de sus padres sino también mucho más sofisticado. Incluso durante las prácticas musicales que los muchachos hacían en la casa, lo cual a veces creaba algunos problemas de comunicación debido a lo complicado que era aplicar un vocabulario más bien técnico en los ensayos. Pero ni Luis ni Felipe intentaron preguntarle a su hermano mayor sobre el motivo de un cambio tan radical en su actitud pues, además de respetarlo mucho, estaban verdaderamente confundidos.

No solo a Ernesto se lo veía más contento, sino que se mostraba mucho más seguro, como si hubiera madurado de golpe; hasta su postura corporal había cambiado, llegando a ser mucho más erguida.

Al siguiente domingo, Ernesto fue el primero en levantarse. Preparó el desayuno para toda la familia, y apuró a sus hermanos para que no llegaran tarde a la iglesia. El primogénito sintió que la misa había durado un santiamén. Al salir del templo, Máximo advirtió que Ernesto se había quedado atrás. Gertrudis regresó en búsqueda de su hijo y lo encontró conversando con el sacerdote. No se animó a interrumpirlos, y volvió a reunirse con el resto de su familia.

Ya de regreso en la casa, Máximo le preguntó a Ernesto cuál había sido el motivo de su charla con el cura. El muchacho se aseguró de que todos escucharan de qué se trataba: se había quejado por la decisión del director de la banda musical de no querer incorporarlo. En esa seria conversación le habló de su preparación como músico y también le dijo que se había sentido discriminado por su forma de hablar. Y le reconoció que tiene un fuerte acento:

-¿Acaso no todos tienen un acento? En inglés o en español, cada ser humano tiene un acento. No importa la lengua que se use, una persona de California habla en forma muy diferente a una de Nueva York u otra de Kentucky. ¿No es verdad, padre? E incluso el vocabulario es diferente. ¿No es cierto?

El sacerdote se había quedado atónito frente a tanta seguridad en un adolescente.

-Pero es que tú mezclas las palabras, hijo –le recriminó el cura.

De repente, Ernesto sintió que una fuerza interior le llenaba el espíritu.

-¿Usted estuvo alguna vez en otro estado, padre?

-¿En otro estado? ¿Por qué?

-¿Sabe cómo habla la gente en otro estado?

-Tengo parientes en Minnesota. Muchos familiares.

-¿Y ellos no hablan en forma distinta que la gente de California?

-Es verdad, pero todos hablan en inglés. Es cierto que usan un vocabulario distinto, pero siempre dentro del inglés.

-Pero el vocabulario, en cualquier lengua, va evolucionando con el tiempo. ¿No es así? Y esa evolución muchas veces tiene que ver con los movimientos migratorios. ¿No es así, padre?

El viejo sacerdote limpió con un pañuelo el sudor de su frente. No podía creer lo que estaba viviendo. Hacía unas pocas horas nomás había estado preparando un sermón con el máximo cuidado posible; había basado sus conceptos en años de estudio y de experiencia. Y ahora un jovencito le estaba tratando de dar una lección… Sin pensarlo, le dijo a Ernesto con voz temblorosa:

-Hoy mismo voy a hablar con el director de la banda.

Ernesto sintió una gran emoción; él mismo no podía creer lo que había logrado. Sus hermanos estaban orgullosos. Su madre también, aunque preocupada por la posible reacción negativa de su esposo. Máximo, tan confundido como el sacerdote, prefirió no emitir ningún juicio de valor. Le dijo a Gertrudis que se sentía mal y que tenía que acostarse un rato.

Al día siguiente Ernesto fue a la escuela cargado de nueva energía. Durante todo el camino pensó en Leticia. Ahora era él quien estaba en deuda con su nueva compañera, pues su corta relación le había hecho entender no solamente cosas importantes de la vida sino también de él mismo. El reencuentro con la hermosa muchacha fue tan natural que Ernesto sintió que era como si se conocieran desde hacía muchísimo tiempo. Ahora prestó más atención a cada uno de los detalles de su amiga: su largo cabello rubio, su estrecha cintura, sus delgadas piernas, su forma de hablar y su caminar cadencioso, y sus hermosos ojos verdes que le transmitían paz, confianza y un afecto que nunca antes había sentido en su vida. Nuevamente pasaron juntos toda la jornada escolar. Hablaron largamente sobre sus familias, y cómo se diferenciaban las costumbres de Texas e Illinois. Y también se entretuvieron charlando sobre las distintas formas de hablar en esos estados. De repente, a Leticia se le ocurrió una idea que podría ser interesante para ambos:

-¿Qué te parece si tomamos una clase de español?

-¿Español? –reaccionó sorprendido Ernesto.

-Por supuesto. Podríamos mejorar nuestra forma de escribir y de hablar.

-Tienes razón. No se me había ocurrido…

-Necesitamos obtener información.

-Hoy mismo voy a hablar con la profesora Méndez –agregó Ernesto, con entusiasmo.

Efectivamente esa misma tarde Ernesto habló con esa docente quien no solo le dio información sino que lo motivó a tomar una clase de literatura con ella.

-¿Literatura en español? Yo no estoy preparado para eso. Es una clase demasiado avanzada –le dijo, preocupado, a la profesora.

Sin embargo, ella le dijo que su nivel de español era lo suficientemente bueno como para tomar esa clase.

Al regresar a la casa, Ernesto les dio la buena noticia a sus padres. Gertrudis se manifestó orgullosa de su hijo. Y Máximo, sin salir de su sorpresa por los grandes cambios que estaba viendo en la actitud de su hijo hacia diversos aspectos de la vida, le preguntó si sabía algo sobre el contenido de una clase de literatura en español. Ernesto les contó que la profesora Méndez le había dado bastante información al respecto, y que no solo iban a estudiar sobre la literatura y la cultura de varios países latinoamericanos sino también de la de los latinos en los Estados Unidos. Por fin iba a poder estudiar sobre temas con los que se podría identificar.

-¿Y son obras literarias escritas en español o en inglés? –le preguntó su padre intrigado.

La respuesta de Ernesto los dejó a todos pasmados:

-Estudiaremos obras en inglés, en español y…

-¿Y…?

-¡Y en espanglish! –agregó Ernesto casi gritando.

-¿Qué…? ¿Estás bromeando, no? –preguntó incrédulo Máximo.

Toda la tarde tuvo que pasar Ernesto explicándoles a sus padres la nueva realidad lingüística de un grupo importante de latinos que viven en los Estados Unidos, incluyendo la realidad de sus propios hijos.

Ese domingo Ernesto decidió ir a la iglesia un rato antes de la misa, para poder conversar con el sacerdote. El cura lo recibió muy amablemente y lo hizo pasar a una pequeña biblioteca sobriamente decorada con objetos religiosos, pero evidentemente poco utilizada. El joven le preguntó si ya le había hablado al director de la banda musical sobre su posible incorporación.

-Hijo: hay veces en la vida en que no todo sale como uno se lo propone –señaló el cura a manera de consuelo.

Ernesto lo interrumpió y con una muestra de fuerte personalidad y seguras convicciones le dijo hablando rápidamente:

-¡Gracias, padre! Estaba seguro de que usted lo iba a poder convencer. Yo sabía que finalmente iban a valorar mi sólida preparación musical, mi dedicación y entusiasmo. Y yo sabía que usted no iba a permitir que se me discrimine por mi cultura diferente. ¿Cuándo puedo empezar a ensayar, padre?

El sacerdote, sin poder salir de su aturdimiento, le dijo, tartamudeando:

-Vamos, vamos a hablar con Mr. Pérez.

Ambos salieron apresuradamente al encuentro del director. El cura, tratando de imitar la energía y seguridad de Ernesto, le dijo a Mr. Pérez que a partir de ese momento el joven era un nuevo integrante de la banda musical de la iglesia. Y le ordenó que le diera los datos sobre el horario y el lugar de los ensayos.

-------------------------------------------------------------

Pasaron varios años desde aquella extraña conversación. Hoy, Ernesto es el director de la banda de la iglesia, y sus hermanos son los dos violinistas principales. La directora del coro es una hermosa rubia de ojos verdes. Los feligreses están contentos con los músicos, y sobre todo se complacen en cantar una nueva canción escrita por el director… en espanglish.-

“She is like Julia in every way.”

Excerpt from The Book of Archives and Other Stories from the Mora Valley, New Mexico by

A. Gabriel Melendez

OPENING TO A PREVIOUS LIFE

Just what are we in this life?

Un costal lleno de huesos,

A sack full of bones.

Y una cosa corrompida,

And rotten stuffing.

¡Ay, ay, cuán amarga es la muerte

Oh how bitter is death

Y qué dulce fue la vida!

And oh how sweet was life!

—Miguel Casías, San Juan, New Mexico, July 7, 1989

Enriqueta’s second daughter was born in the first days of the influenza, and her birth brought hope and joy. Cándida had the blue eyes of her German great-grandfather and the soft dark skin of her mestiza great-grandmother. Enriqueta cradled the child in her arms and nursed her with the sweet milk of her breast in the amber light of the oil lamps that lit the rooms of her home.

One Saturday afternoon, Enriqueta felt soreness in her shoulders and she retired to her bedroom even before the sun had gone down. She laid Cándida beside her in the bed and picked up her missal and prayed the Divine Praises in preparation for hearing Mass the next morning. She could not keep her eyes open and left off reading at the epistle for the first Sunday after Epiphany at the verses “Be patient in turbulence and persevering in prayer.” She slept until Cándida’s cries woke her. So deep was her sleep that at first she thought she had only napped, but her breasts were heavy with the night’s milk and she thought, “I must nurse Cándida.” At midmorning, Enriqueta began to shiver with chills and she complained of drafts through the house. Corina Lucero, the médica that attended her, did not let her up from bed, and Enriqueta slept soundly for several more hours. She awoke drenched in a copious sweat that had formed an outline of her delicate body on the sheets of her bed. On Sunday afternoon, Cándida began to show the first signs of having contracted her mother’s illness, and Corina Lucero had her crib moved to an adjoining room where she could better watch over the child. Cándida’s eyes had lost their natural brilliance and had dulled to the color of gray river rock. She cried and dozed in fits and spurts. The silver sliver of a waning moon hung over La Jicarita, and Cándida’s shrill cries threatened to rend the ice-blue sky of that January evening.

At a quarter to seven on the morning of the second day, Enriqueta spoke, but her words confounded those around her. She looked at Corina and said, “Are you the devil?” and pointing at the darkened corners of the room, she continued, “And are they your consorts?” She rubbed her fist against her left eye and shouted, “This horrid smoke, it burns my eyes! Open the dampers on the stoves!” Then she fell into a deep coma and did not regain consciousness. The fever continued to consume mother and daughter, but try as Corina might, nothing she did quelled its progress. Neither the sponge baths, nor the paper-thin slices of potatoes to cool the forehead, nor the herb tea, nor the prayers to San Ramón broke the fever’s grip. At nine o’clock on Tuesday morning, Enriqueta’s breathing sounded like sand running through a sieve. Corina strained to hear a heartbeat. It was distant, like thunder in a snowstorm. The old woman advised the family: “Call the padre, Enriqueta is at the very edge of this life.” The Dutch priest, Padre Munnecom, was presiding over a funeral at Chacón in the upper valley and did not arrive till midafternoon. After giving Enriqueta the last rites, he said, “She is dead. Bury her quickly.” Before leaving, he inquired about the child’s health. Corina looked down at the floor and answered, “Gravely ill, she is very weak, Padre.”

A delegation of penitentes came to bury Enriqueta. After praying over her, those hermanos who had known her grandmother as a young woman asked each other, “How can it be that one person can be reborn into life as another?” They did as the family asked and buried Enriqueta next to her grandmother, Julia Pacheco de Steiner. They lowered the simple wooden casket into the darkness of a fresh grave at the upper campo santo on the road to the village of El Oro. Enriqueta’s sister, Lourdes Paiz, her eyes swollen and red from days of mourning, had reached her wit’s end with worry and fatigue. That evening as the family gathered to console themselves and fortify their weary bodies with sweet breads and strong coffee, Lourdes lost her composure when the old woman Corina said in resignation, “It must be God’s will.”

“Shut up, you old witch,” cried Lourdes, “if we didn’t have to depend on your foolish remedies and your useless hand-wringing, Enriqueta would be alive now! Look at the Americans,” she said, “their doctors keep them from such misery.” ’Mana Corina responded, “Child, the American doctors have their understanding of things and I have mine. But it seems that compassion is not a part of their science of things. Have you ever seen an Americano doctor cross the threshold of one of our homes? It is what we have, mi hija, foolish remedies, cure patches, and tea baths like those that cooled your old man Romaldo’s body when his skin peeled back from his flesh after the boiler exploded at Don Tito’s sawmill in Chacón.”

When Lourdes was calm again, she said, “Forgive me, Corina. It’s just that these blows that life has dealt us have been so fierce. I did not mean to blame you. You have done what you could. When Cándida’s fever breaks, send her to me.” Lourdes continued, “I will raise her and she will not want for anything nor will she know what it is to be an orphan.”

Cándida’s crying subsided, drifting into quiet sobs, then stopped altogether, but the fever would not break. Like her mother, she fell into a coma and her life grew fainter and fainter as the hours of the night pushed toward the new day. At seven the next morning, her tiny body wrenched in violent spasms and she coughed up a wad of mucus and coagulated blood. An hour later she was cold and her arms stiffened like the limbs of a doll. Her eyes were open, but she was dead. Cándida was dressed in a white gown. Corina placed a pair of brown shoes on her feet and on her head an ornate crown fashioned from an old piece of tin. Then she placed a branch of piñón wrapped with faded crepe paper and adorned with gourds for a staff at the child’s side. She was presented to her mourning family as an angelita, a little angel, because she had died without knowing either the stain of evil or the false joy of this world. All during Mass and during her Rosary, the villagers imagined Cándida’s soul winging its way to heaven along the shafts of sunlight that pierced the rolling winter clouds above them. ’Mana Cortina refused to follow the cortege to the cemetery and she turned back at the first stop. “This sickness be damned,” she cried as she touched Cándida, lying in the black cardboard casket, one last time. “Little messenger,” she whispered, “tell Almighty God in his Glory that his people suffer much upon this earth. Tell him, my child, in case He has forgotten us.”

Lourdes Paiz asked that as a proper and fitting thing the infant Cándida be interred with her mother. Again the penitente brothers opened the grave they had closed only a day earlier. The wet earth sliced open like clay on a potter’s wheel until their shovels sounded hollow drumbeats upon Enriqueta’s pine coffin. The men heaved, grasping at the edges to pry back the coffin’s lid and deposit the infant daughter. In the dark pit they drew back the white shroud, their lanterns swinging high over Enriqueta’s face until they could see it clearly.

“Ay, Dios,” came up the gasps of the men who were waist deep in the shallow grave. Enriqueta’s eyes were open and her face was contorted, her mouth agape as though locked in a silent scream. Her hands were not clasped upon her chest in peaceful repose, but were tangled in the long strands of Enriqueta’s raven black hair. Her fists were full of the tufts of hair she had torn from her head. “Ay, Dios mío,” those at the graveside shouted in horror as they stepped back, “Enriqueta was buried alive!”

POR LA RENDIJA DE UNA VIDA PREVIA

¿Qué somos en esta vida? Un costal lleno de huesos, Y una cosa corrompida,

¡Ay, ay, cuán amarga es la muerte Y qué dulce fue la vida!

—Miguel Casías, San Juan, Nuevo México, 7 de julio de 1989