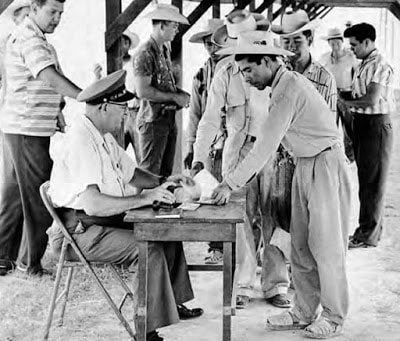

Coming of age on the migrant streamBy Rodolfo Alvarado From my place in line, I could see my brothers and sisters acting silly in the back of our station wagon, La Blanca. I could also see my amá. She was sitting in the front seat staring straight ahead. She was probably praying. She always prayed until she knew, for sure, we had the job that would get us through the rest of the year. Seeing me looking at her, she waved and smiled. I didn’t act silly anymore, but to make her feel better, I hid behind my apá and then peeked at her before hiding again. As I kept hiding and peeking, her smile got bigger and bigger. We were playing Peek-a-Boo. I’d played the game with her ever since I was a baby, and to make her happy, since the first year I’d waited in line. I was eight then, thirteen now, about to be fourteen. I guess we were having fun, but before she could take her turn, my apá asked me to go and get the letter from the American Government showing he had permission to work in El Norte. He’d forgotten it in the glovebox. Running up to my amá, I explained what had happened. She found the letter right away and as she handed it to me, she said, “Standing in line, Junior, you look like a big boy.” Hearing her, my brothers and sisters made funny faces at me behind her back. It didn’t bother me because they still acted like babies, and I was becoming a man, like my apá. Walking back, I think some of the campesinos thought I was cutting in line because they started looking at me kind of funny. To remind some, and to show others, that I’d already been in line, when I got closer, I waved the letter, yelling, “¡Apá, apá, encontré la carta!” Some stopped staring, but others kept looking at me until they saw me hand the letter to my apá, and then take my place in line behind him. It took close to thirty minutes for me and my apá to reach the front of the line, and when we did, my apá gave the letter to the foreman. The foreman looked it over, asking, “You, Emilio Rodriguez, Sr.?” Knowing the foreman was always in a hurry, my apá answered his questions as fast as he could. “Yes,” my apá answered. “From Piedras Negras, Mexico?” “Yes.” “Speak-ah la English?” “Yes.” “How many to work?” “Seven.” “That includes you and your wife, right?” “Yes, and our children.” “How old are they?” “Junior’s thirteen, Lala’s twelve, Juan Daniel’s….” “I don’t need their names, damn it, just their ages. How old are they?” “Thirteen, twelve, eleven, nine and eight.” “The eight-year-old? Is that a boy or a girl?” “A girl.” “This her first time?” “Yes, sir.” “You think she’s ready? We got us a big crop this year. We’re gonna need everybody workin’ every minute of every hour of every day. We don’t need her slowing you or your wife down, ¿comprende?” “No, señor, she will do a good job; all of them will do a good job. Four of them were here last year.” Leaning forward on his desk, and his eyes getting mean, the foreman said, “She better, or you’ll find yourselves out of a job quicker than you can say Speedy Gonzales.” “Sí, cómo no.” The foreman wrote my apá’s name in the red book with the blue lines. Next to his name, in the place for men, he wrote a one. In the place for women, he wrote a one, and in the place for children, he wrote a five, then he told my apá how much we were getting paid. Since I’d waited in line, the most my apá had ever made was a dollar fifty an hour, my amá one dollar and me and my brothers and sister, fifty cents. So, when the foreman told my apá he’d be making three dollars an hour, my amá two dollars, me and my older brother and sister a dollar, and the two youngest fifty cents, my apá turned and looked at me. I could tell he was wondering if I had heard the same thing. I had. I was thinking the foreman had gone loco, and I knew my apá was thinking the same thing, too. The foreman wrote how much we were getting paid on a yellow card that looked the same as the one he gave us every year, then he asked if we wanted to rent a camp house. “Yes,” my apá answered. The farmers we worked for rented us campesinos, these little houses, what we called, casitas, and they called camp houses. The cost to rent a casita changed from year to year. If you were paid a lot, a casita cost a lot, and if you were paid a little, a casita still cost a lot, but not as much as if you were making a lot of money. If you wanted, you could rent a place in town, but it cost more than a casita, and you had to drive to work every morning, so most campesinos rented a casita. Most of the time casitas were rented to families, but on my first trip I saw at least fifteen men staying in one casita. When I asked my apá why, he said that, “Sometimes, a man had to do, what a man had to do.” “It’ll cost you thirty-five dollars a week,” the foreman said. “You still want it?” “Yes,” my apá answered. “Please.” We worked close to ten hours a day, so I knew there’d be no problem paying the rent. The foreman wrote the number C-11 on the yellow card. The letter C stood for the camp and the number 11 for the casita we’d be renting. There were eight camps in all and each camp had fifteen casitas. So far, I’d stayed in H-2, E-4, B-7, and in C-8, two times. The foreman handed my apá the yellow card, saying, “We'll expect you all ready by six tomorrow morning and since we have a bumper crop, we’ll be working seven days a week, ¿comprende?” “Seven days?” my apá asked. “Seven days,” the foreman said, “you gotta problem with that, there’s the door.” “No, señor,” my apá said, “no problem.” Finished with us, the foreman yelled, “Next!” My apá thanked him and as we walked out of the office and past the other campesinos in line my apá’s walk was tall and proud, and mine, mine was almost the same. When we reached La Blanca, my apá handed the yellow card to my amá. As she read it, her eyes got big. “Is this for real, Emilio, three dollars?” Shaking his head up and down, my apá said, “And you, you and the children, did you see how much you make?” “Yes,” she said. “I did. I did.” My amá smiled really big, held the card against her heart and closed her eyes. She prayed and when she finished, crossed herself. I knew my apá had more to say because he hadn’t started La Blanca. “We’ll be working seven days a week.” “Seven days?” my amá asked. “Seven days,” my apá echoed, quietly. I didn’t know if my apá or amá had ever worked seven days a week, but I knew me and my brothers and sisters never had. Working six days a week was hard, and I knew seven was going to be harder, especially for my little sister. “What about church,” my amá asked, “and going to the store? What are we going to do?” Starting La Blanca, my apá said with a smile, “Don’t worry, we’ll find a way. We always do.” My brothers and sisters didn’t hear what they were saying because they were too busy talking about whether or not we were stopping at Pete’s and then the park. We didn’t go to Pete’s, and the park across the street from Pete’s, every year. We only went when our parents knew we’d make enough money to help us through the rest of the year. Since I’d made my first trip to El Norte, five years ago, I’d been to Pete’s, and then the park, two times, so when my apá said we were going to Pete’s and then to the park, my brothers and sisters went crazy, but nobody went crazier than my little sister, Esmeralda. She let out a grito. I’d gone to Pete’s and the park my first year, too, so I understood why she was so happy. In the years before, she, like me and my brothers and sister, had stayed with our amá’s parents, Abuelito Louis and Abuelita Cruz, until we were old enough to work. In the two times I’d been to Pete’s, we always got our own cheeseburger and Coke, but all of us, even my apá and amá, shared french fries, but this time, we all listened as apá ordered cheeseburgers, Cokes, and an order of french fries for each of us! Hearing this, my brothers and sisters really went crazy. My amá told them to behave, and most of the time they did, but this time they didn’t listen, not until amá said there’d be no going to the park unless they settled down. No’mbre, they turned into little angels until we got to the park and they finished eating. After that, you couldn’t stop them. They were ready for some fun, and to be honest, I was too, because I knew that after today there’d be nothing but seven days a week of hard work. My apá and amá always played with us right after we ate, but this time they told us to go ahead, that they’d join us after they were done talking. From the top of the slide, I could see them sitting on the blanket where we ate. I wondered what they were talking about and the words they used, and, as I wondered if I’d ever fall in love, get married and have children, they smiled at each other, and my apá put his hand on my amá’s cheek and kissed her. Amá always gave him a quick kiss when they were outside or me and my brothers and sisters could see them, but this time, I think she forgot they were outside and we were around, because she kissed him for a long time. When they finished kissing, they came and played with us. They rode and pushed us on the swings, went down the slide, and played freeze tag. They played Duck-Duck, Red-Rover, Red-Rover, and hide-and-seek. Everyone had such a good time that it was hard for me to tell who was having more fun, my apá and amá, or my brothers and sisters. When the sun started going down and the mosquitoes got to be too much, we drove to El Gallo to pick up things like bologna, flour, eggs, milk, coffee, ice, and toilet paper. My apá and amá were the only ones who ever went into the store. Being the oldest, it was my job to take care of my brothers and sisters. I never liked babysitting them because I never knew if they were going to listen to me or not, but this time, I got lucky because my littlest brother and sister fell asleep and my brother, Juan Daniel, read a book, while my sister, Lala, worked on a word search puzzle. By the time my apá and amá were done at El Gallo, and we got to Camp C, the other campesinos and their families were already having their dinner. Most ate burritos they made before leaving home. We were no different. It made the first night at the camp easy on everybody, especially mothers. Inside, las casitas were the same. You walked into a big room. Part of it served as a living room and the other part a kitchen. The only door inside went to the restroom. We only had cold water and the floors were made of cement. The living room had a small table, two chairs, a coffee table, and a small bed. My sisters slept in the bed and the rest of us on the floor. The kitchen had a small refrigerator, a small stove, and a sink. A cabinet hung above the sink. Inside there were different colored plates, glasses, and bowls made from metal and under the sink were some pots, pans and a box of forks and spoons—big and small—for eating and cooking. My amá never used any of those things, she brought her own. The restroom had a toilet, a small shower and one hook to hang towels. Our amá made us take a shower every day after work. I didn’t mind because I was the oldest, which meant I got to go first, after my amá and apá. There were only two windows: One beside the front door and a smaller one in the restroom. From the restroom window I could see the cotton fields and the clothes lines where we hung our wet towels and our amá the clothes she washed every Wednesday and Sunday. I liked looking out the restroom window. I’d think about those who’d worked the fields before us, and then, I’d whisper a prayer for them, a prayer that all their dreams would come true. After praying, I used my pocket knife to scratch a small cross under the window. To see it, someone would have to be looking for it. I thought of it as a gift, un regalo, for anyone special enough to find it. The next morning, and every morning after that, we woke up at five. We ate a bowl of atole with a slice of butter on top, and while we got dressed, our amá made our lunch. Walking outside she gave each of us a sack and a gallon of water. Inside each sack were two bologna sandwiches, a small bag of Fritos, an apple, and in each gallon of water, there were always a few pieces of ice. We thanked our amá and as we waited for the truck to take us to work, our apá told us not to eat until the foreman gave us permission, and to drink our water slowly, or we’d get sick. Then, he’d tell us to make him and our amá proud. My brothers and sisters knew this meant the time for acting silly was over. The mornings were cold, and when the sun came up, the day was hot. We wore gloves and bandages on our fingers, but they still bled. We filled burlap sacks with cotton, and when they were full emptied them into a trailer. You had to work fast and keep going, no matter what. When I was eight, and I picked cotton for the first time, I cried and told my apá and amá I didn’t want to work, that it was too hard. They asked me to stop crying; to stop before the foreman heard me. They told me I was doing a good job and then took cotton from my sack and put it in theirs, and when they saw it wasn’t enough to make me stop crying, they told me to pray to la Virgen de Guadalupe for strength. I did, and when I finished praying, my apá said, “Aguántate, mijo, aguántate.” I’d never heard the word aguántate before, so I asked my apá what the word meant. He told me that it could mean a lot of things, but to him and my amá, it meant to use what life gives you to make you stronger. Some men, women, and children, like me and my older brothers and sisters, understood what the word meant, but others did not. They were the ones, as our apá and amá taught us, who complained about the hot sun, the low pay, the foreman’s watchful eye, or ran away in the middle of the night before all the cotton was picked. I did as my apá and amá taught me, and as I grew up, I never told anyone about being hot, thirsty, or hungry, but that was me. I wish it could’ve been that way for my little sister, Esmeralda, too, because on the first day of work, she started crying, and even after our parents talked to her, she couldn’t stop, and the harder she tried, the harder it became for her to work. Our apá and amá tried and tried to get her to stop, but she wouldn’t. When the foreman saw and heard how she was acting, he pulled his horse around. As he rode closer, my amá told me and my brothers and sister to keep working. Riding up to my apá and Esmeralda, the foreman yelled, “What’s going on?!” “No,” my apá said, as he got up and stood between Esmeralda and the foreman. “She’s okay. She’s okay.” “She’s yours!?” the foreman yelled. “Sí, señor,” my apá said. “Well, if she’s yours,” the foreman yelled, “you better get her back to work before I have to do it for you! You understand me, boy?” “Sí, señor,” my apá said—said as he quickly turned around, and, in a voice I’d never heard coming out of his mouth, yelled, “Esmeralda get to work and stop crying, stop crying, now!” My little sister had never heard him talk that way, too. It scared her—scared her so much that she stopped crying and went to work, right away. “What’d I tell you, Paco,” the foreman yelled at my apá, “your kids keep you from working and you’ll find yourselves out of a job faster than you can say Speedy Gonzales!” Thinking my apá needed help, I cried out in a voice—a voice just loud enough so the foreman wouldn’t think I was being disrespectful, “I’ll help her!” “Junior!” my apá yelled. Riding his horse right up to me, the foreman asked, “What did you say?” “I said, I can help her.” “Help her?” the foreman asked. “Help her what?” “Work,” I said, as my apá called to me again, “Junior!” “You think,” the foreman yelled, as he got off his horse, walked up and put his face right in front of mine, “that we’re paying you a dollar, a goddamn dollar an hour, to help someone else do their fuckin’ job?!” I didn’t know... didn’t know what to say. The foreman leaned his face closer to mine, yelling, “I asked you a question, boy!” I looked at my apá, and he looked at me. There was a distance, a distance between us—a distance where a boy—a boy suddenly found himself becoming a man—a man who could no longer turn to his apá to correct a mistake he’d made on his way to growing up. But, there was also the look in a father’s eyes, a look that said, “No, no, my son, my little boy, I am not yet ready to let you carry the load of this world on your shoulders.” My apá pulled off the strap to his burlap sack and ran as fast as he could to me and the foreman. In the same voice he used with Esmeralda, he yelled, “Get to work, Junior, now!” I did as he ordered, and then he started talking to the foreman in a voice loud enough for only the foreman to hear. Seeing this, my amá told me and my brothers and sisters to work faster. She said it in a shaky voice I’d never heard coming out of her mouth. The sound of it scared me, and as I looked around at my brothers and sisters, I could tell it scared them, too. All of us started working as fast as we could, and when I peeked at my apá, I saw the foreman staring at him with a look in his eyes that I understood right away to mean that the work and the money that would see us through the rest of the year were in his hands. In his, and no one else's. With a final word and a small bow, my apá ran back and got to work. Behind me, I could feel the foreman staring down at us from the top of his horse. He wanted us to slow down; for Esmeralda to make a sound; for me to open my mouth; for my apá or amá to check on how we were doing—anything, so he could yell at us again or tell us, as I’d heard him tell others, “What did you wetbacks think this was gonna be, a mother fuckin’ siesta?!” I was afraid, so afraid that I wanted to cry out to my apá and amá to keep me safe, and if I felt this way, I wondered how Esmeralda must feel, and how my apá and amá must feel, too. I’m not sure how long the foreman watched over me and my family. I only know it was long enough that I forgot about him and of being afraid. For the rest of the day I didn’t talk to my apá and amá, and they never talked to me. But after work, when we were riding in the back of the truck, going to the camp, I apologized to my apá for what I’d done. He didn’t say anything for a long time, and I knew it was because he couldn’t find the words to tell me how much I’d almost cost my family, but when he finally spoke, he said one word, and one word only, the Spanish word for look. “Mira,” he said, as he lifted a finger and pointed at our family. My amá held Esmeralda in her arms. They were both asleep and my brothers and sister rode on the other side of them with their heads between their raised knees. I couldn’t tell if they were asleep or just resting. As the truck drove on, I lowered my head between my raised knees, too. I thought about what I’d done; of what my apá must’ve said to the foreman to keep him from firing us; of Esmeralda crying; of my father yelling; of the fear in my amá’s voice; of the look in the foreman’s eyes; of my apá bowing and running back to his burlap sack; his getting back to work as fast as he could, and when it all became too much, I said a prayer to La Virgen de Guadalupe, and when I remembered that there’d be no going to church until we got back home, I began to cry, to cry quietly to myself. The next day, and for all the days after that, it didn’t matter if the foreman was watching me or not, I worked harder than everybody else. I never said a word to my apá or amá unless they spoke to me first, and, I said a prayer to La Virgen de Guadalupe every night as we drove back to camp. Doing all of this made me feel better, but when Sundays came I couldn’t keep myself from thinking about what I’d done and feeling sad about not being able to go to church. I missed our Sundays off from work; missed the smell of my amá’s tortillas and the chorizo burritos she made for breakfast; us dressing in the clothes our amá ironed the night before, and then driving to church, where Father Felipe waited to say, “Buenos días.” I also missed the men talking by themselves after Mass. I watched them from La Blanca, wondering what they talked about, and when I’d be old enough to join them. Yes, I missed all of that, but most of all I missed getting to do whatever we wanted when we got back to the camp and changed out of our Sunday Best. Sundays were the only days everyone got to do what they wanted. The youngest ran through clothes hanging on the line, played chase, or freeze tag. Those a bit older flew kites, played marbles, or pitched pennies. The oldest, those of us who, like our fathers and mothers, had grown up playing all the games that came before, now played baseball or kick ball. All the while our fathers and mothers sat around campfires talking to each other; the men in one group, the women in another, and when the day was done, families said their good nights and then drifted inside their casitas. My amá would make tortillas and cook us a special dinner. On some Sundays enchiladas, on others burritos y tacos, and still others carne asada, and always, always with a side of arroz, frijoles, chile verde, and to drink, a glass full of ice and orange Hi-C. After we were done eating, we’d listen to Spanish music on the radio. My apá and amá played cards and dominos, while the rest of us spent time doing whatever we wanted; the only rule—the only unspoken rule—was that whatever we did, we had to do it quietly, and not because our apá and amá needed a break from all the noise, but out of respect for the suffering Christ had endured on the cross for our sins. The next morning, the men, women and children, who the night before had been the best of friends, treated each other like strangers. It’s funny, but that’s the way our world worked: There was a time to play and a time to work. For the rest of the time that we were there all of us worked hard, and by the time we were finished picking all the cotton, Esmeralda not only worked harder than me, her pay went from twenty-five cents back to fifty cents an hour. She never said anything bad about anything and when lunch time came she never opened her sack until the foreman said we could, but on the last day, as all the campesinos and their families waited for the foreman to show up so we could get paid, I was reminded that Esmeralda was a little girl when she cried saying adios to her new best friend, Manuelita. By the time the foreman arrived, the men, and only the men, were already standing in a line in front of Casita #1. It was there where the foreman always set up his table to get everyone paid. This time was no different. The foreman parked his shiny Ford truck in front of Casita #2. The first two men in line helped him set up his table and chair, while the foreman took the metal box with all the money inside and sat down at the table. Sitting in La Blanca, I watched as the foreman handed the men an envelope with all the money they were owed, and if they had a family, the money owed to them too. No one counted their money. You were paid what you were paid. If you didn’t like it, don’t come back. As they were paid, and they turned away from the foreman, their walk was tall and proud, and their smiles grew bigger and bigger until they hugged their wives and handed them the envelopes with enough money inside to see them through the rest of the year. Watching my apá move up in line, I wondered what he was thinking and if he’d truly forgiven me for what I’d done, but above all, I wondered when I’d be able to stand in the line with him. With his pay in hand, my father turned away from the foreman. His walk was also tall and proud, and his smile grew bigger and bigger until he sat in La Blanca and handed our amá the envelope. My amá gave him a quick kiss and a hug and then led us in a prayer of thanks. After that, the both of them thanked me and my brothers and sisters for our hard work. It’s funny, but I never once wondered why they got to keep all the money we’d earned. Thinking back on it now, I know it was because my apá and amá didn’t raise me to think that way. No, I always prayed and gave thanks for my family, and when I thought about how much I had almost cost them I wanted to cry, but I didn’t. I didn’t because I knew a man would never do such a thing. As always, I fell asleep on the way home, and as always, since my first year of making the trip to El Norte, I did nothing but dream of picking cotton. Sometimes, I dreamed about a row of cotton that never ended or about a bag of cotton so full I couldn’t move it no matter how hard I tried, but this time I dreamed that the foreman was seated on top of his horse yelling at me, while Esmeralda cried behind me. His eyes glowed brighter and brighter and just when he was about to destroy our world with his eyes, my apá and amá ran and stood in front of me and Esmeralda, and the foreman, seeing his power lost, turned his horse around and quickly rode him away. I had these dreams for the longest time, and it always seemed that just when I started dreaming about something else, the time to go back had arrived. This time was no different. Summer was almost here and with it my dreams about cotton were coming to an end. I was fourteen now, about to be fifteen. I was eager, not only to go and work, but to show my apá that I had learned my lesson from the year before. Yes, I was ready, but this time something happened, something I did not expect. When we got home from church, my apá and amá called me and my brothers and sisters into the living room. I didn’t know what they wanted, but I knew it must be important, because it was the only time they ever talked to all of us at once. Me and my brothers and sisters stood quietly until my apá finally spoke. “When we were little, me and your amá, we had to work the cotton fields with our families every summer. Not one time did we ever get to stay in school or have a summer to do nothing but run and play. “It has always been our dream for our children to stay in school, and when it ended, have the whole summer to do nothing but run and play. “Our mothers and fathers shared the same dream, but for them the dream never came true, but thanks to the money we earned as a family last year, it is a dream that has come true for me and your amá. “This year, I will be the only one going to El Norte. All of you will stay in school and when school is over, you will have nothing to do all summer but run and play.” Hearing this, my brothers and sisters went crazy, and Esmeralda kissed our apá and amá on the cheeks and said, "¡Gracias, apá! ¡Gracias, amá!" and then she and the rest of my brothers and sisters ran outside to play. But me? I stayed inside. I didn’t move or say anything. My amá asked if I was okay, and when I didn’t answer, my apá said if I had something to say, to say it. I didn’t say anything right away, but when I did, I said I didn’t want to stay home, that I wanted to go and work, that I needed to work for our family. “I want to be a man, apá, a man like you and the other campesinos.” Finished talking, I didn’t cry, feel sad, or act silly, because I knew a man wouldn’t act that way. When the evening before our trip arrived, I washed La Blanca and the next morning me and my apá loaded what we needed for the trip before the sun came up. We gave amá a kiss goodbye and then we got into La Blanca. A sack full of burritos rode between us and at my feet were two gallons of water with pieces of ice floating inside. My apá said a prayer for our safe travels, and as we drove away, he slowed down, and looking into the rearview mirror, said, “Mira.” I turned and looked. My amá stood at the screen door and my brothers and sisters were outside waving goodbye. They had grown a year older, but as I turned and faced forward, I prayed, prayed that they’d remain children for as long as they could. It took me and my apá less than six hours to drive to the office where campesinos were hired. We stopped once to use the restroom, so the line was short—as short as I’d ever seen it. Standing behind my apá, I pretended my amá was sitting in La Blanca and that we were playing Peek-a-Boo. I took a turn, and she took a turn and when we were finished, I stared straight ahead, like my apá. When our turn came, my apá handed the foreman the letter showing he had permission to work in El Norte. After looking it over, and writing down my apá’s name, the foreman asked, “Speak-ah la English?” As my apá said, yes, that yes, he spoke English, I wondered if the foreman ever remembered any of the campesinos he saw year after year, or even those who’d grown from boys to men right in front of his eyes, and as the foreman asked, “How many to work?” I smiled, as my apá said, “Two, only two.” Hearing him, and with his eyes getting bigger, the foreman looked at me, not my apá, and asked, “Did he say two?” “Yes,” I said. “Yes, sir, two.” Looking like he’d just woke up from a dream, a bad dream, about cotton, the foreman stood up and looked down the line. He leaned to one side and then the other, and then he looked out the window to where the cars and trucks were parked. There were no wives or children to be seen. He lifted his cowboy hat, scratched his head, put his hat back on, and as he sat back down, he said, “What is it with you lazy Mescans, you make some good money one year and the next don't one of you show up to work.” Me and my apá listened, but we didn’t say anything. “One dollar and seventy-five cents,” the foreman said, as in the red book with the blue lines, he wrote the number two next to my apá’s name under the place for men. “A camp house is twenty dollars a week. You want one?” “Yes,” my apá answered. There’d be no stopping at Pete’s and the park, but I didn’t let it bother me, because I knew a man never spent money he didn’t have. The foreman wrote G-8 on the yellow card, and as he handed it to my apá, he said, “We'll expect both of you ready by six in the morning. We’ll be working Monday through Saturday. Sunday’s off. Next!” I’d never stayed in Camp G before, but I knew it didn’t matter, because the restroom had a window—a window where I’d be able to look out on the clothes lines and the cotton fields and say a prayer of thanks for having Sundays off and for my parent’s dream coming true, and when I was finished, scratch my mark of the cross under the window. As me and my apá walked out of the office, and past the other campesinos in line, his walk was tall and proud, and now, so was mine. I wanted to ask him if he’d seen where the foreman had written the number two, but I didn’t, because I knew a man didn’t need anyone telling him—or showing him that he was a man. He knew he was a man and that was it, the end of the story. Once inside La Blanca, my apá didn’t start her up right away. I knew—knew then, that he had something to say, but instead of talking, he looked away from me, and then, he made a sound, a sound I had never heard coming from him before. He started crying—crying like a man, then a young man, then a teenager, then a boy, then a baby. I didn’t say anything, because I knew it was what a man would do. Instead, I did what I knew a son would do. I held my apá, closed my eyes, and listened, listened to time floating by. I thought about him, my amá, my brothers and my sisters, then I prayed that one day I’d be able to give them all their summers off, so they could do nothing more than run and play.  Photo by Natalio Alvarado Photo by Natalio Alvarado Rodolfo Alvarado is a native of Lubbock, Texas, now living in Ann Arbor, Michigan. This story is based on experiences gained while working the cotton fields of West Texas as a boy with his family. His fiction and non-fiction have been published by Arte Público Press, the University of Michigan Press, Texas AandM University Press, El Central, El Editor, and Alpha Books of New York. Noted publications include,Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in Michigan for Michigan State University Press and The Untold Story of Joe Hernandez: The Voice of Santa Anita. This biography won the Dr. Tony Ryan Book Award and was a finalist for an International Latino Book Award. He holds a Fine Arts PhD from Texas Tech University and has taught at the University of Michigan, Ave Maria University, and Eastern Michigan University, where he was a Parks/King/Chavez Fellow and a University Fellow. This is his first story for Somos en escrito.

0 Comments

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed