I Migrated to the US to Escape a Demonby Javier Loustaunau People have asked me a bunch of times why an industrial engineer like myself would move to the USA and become a custodian. I think life is just more predictable here, the laws seem a lot more settled. When I say the law is looser in Mexico, I’m not just talking about bribing your way out of a parking ticket. The laws of physics, metaphysics, reality… they seem less predictable. You might stop at an amazing restaurant late at night while drunk and then never find it again after you sober up. People all over are getting “limpias” or aura cleanses to break streaks of bad luck. Don't even get me started on stories about Smurf dolls that bite children, which seems really funny until you are alone with one. That is the way these urban legends work I guess, they all seem really funny when you first hear them but then when you are alone they are creepy as hell. That is in part why I moved… I was spending too much time alone, creeped out while working overnights, praying under my breath. Our country is very catholic, even if the government is not supposed to be. That's me, engineer on the outside, a dozen candles with saints and the Virgin Mary burning inside me. We are surrounded by progress yet we continue to see the devil in all aspects of our lives. He makes food spoil by tasting it if you leave it unattended. He dances with gorgeous young women at parties until they realize he has one foot like a goat and another like a rooster. He shows up as a huge dog and trashes your business. Most stories are mischievous and end with him being scared off by prayer, these stories are ultimately empowering to believers. One day I heard a story I really did not like, especially since it took place on the highway from Los Mochis to Topolobampo which I drove through alone at night for work. Back then I worked at the oil refinery. I mostly ran around fixing leaks and sensor errors. I was fresh out of college and really grateful to instantly get a job in my field which would likely set me up for life with a series of small and evenly spread out promotions. In a few years I would be a supervisor, then in a few years a daytime supervisor, and finally I would have my own office and working nights would be a distant memory. But I never made it to my first promotion, because of that god damned road and a scary story. I had been at a party which was kinda low key, nobody had brought beer, we were really just snacking and drinking soft drinks and telling scary stories. Then somebody asked me, “You take the road to Topo, don't you, to the refinery? I heard a really scary story about that road.” And they told me the story, about a ghostly baby that appears in the seat next to you and tries to get you to look at it’s teeth, but if you do it will lunge for your throat, so you have to ignore it while it repeatedly says “mira mis dientitos.” “Look at my little teeth.” My friend laughed. All my friends laughed. I pretended to, but deep inside I was actually really angry. I knew a seed had been planted in my head and now my drives to work would be really creepy. For the next few weeks I would feel my chest tightening on my way to work, driving at night with banda or corridos playing. I could no longer nap at work, and after my morning drive it would take me a while to really relax. Sleeping during the day is weird, you listen to so much traffic, so many honks and car alarms. Dogs bark more, birds chirp. But it was usually the sound of children playing that would wake me up from a dead sleep. I could not make out what they would say but I was primed to hear the voice of a kid next to me, insisting I look at him. I was a wreck for a while, and I drank a lot of coffee to make sure my car did not end up a wreck, too. Finally one night I’m on my way to work around 11:30 to start at midnight. There is a whole lot of nothing along that part of the road, just dried brush, billboards and occasional exits to farms or small towns. Then I felt the presence before I even heard it, my whole body just kind of cramped up and I felt an intense chill. There was also a smell, it smelled like fireworks, mold and earth. It was not pungent enough to make it hard to breathe, but it was certainly menacing. And then I heard the voice, childlike and casual saying, “Señor, mira mis dientitos.” “Sir, please look at my teeth.” It was the moment I had been dreading for the last month, suddenly every muscle in my body contracted and ached all at once. It could not be real though, obviously I was just super tired, super primed, super obsessed with this one event so my mind was playing tricks on me. But then again, a little louder I heard, “Sir, please, look at my teeth.” I wheezed as all the air escaped me, and I fought to catch my breath but my lungs took a second to respond. It was actually happening after all that time dreading it, but I was not about to acknowledge it. I ignored the voice and kept driving. That is when I realized that my music had turned off, I went to raise the volume but for some reason it was not playing. I turned the knob all the way and nothing happened. “Sir, don't ignore me, all I want is for you to look at me.” I was alone with that thing in silence, so I kept my eyes forward and watched the road. “Sir, please why are you ignoring me?” it said, sounding more desperate, more frustrated, more like a child who needed help. “Sir, please!” I continued to ignore it, the drive was short and I knew I would make it to the parking lot if I could hold out 15 more minutes. “Sir, look at me! I promise I don’t bite…” There was a hint of malice in that last statement, I could almost hear a smirk. Involuntarily, my peripheral vision turned just a little, just to confirm that it was smugly toying with me, and then my vision darted back to the road. I had seen a shape, black and gray, like something burnt and buried and dug up again. I saw no eyes, no reflections, just darkness. But it was not an object, not a corpse, it was swelling and deflating in big breaths and its arms had been moving when I caught that glimpse. I felt light headed, my hands swerved a little but I quickly righted them and fixed the steering wheel in their tight grip. I wanted to cry I was so scared, and so angry that this was happening to me, that this possibility had even been planted in my head in the first place. But I did not sob or scream, I started to pray. “Padre nuestro, que estáas en el cielo, santificado sea tu nombre.” As I muttered under my breath the presence grew more agitated, with more urgency in its voice. “Señor, mira mis dientes!” it cried. “Señor… señor… stop praying and fucking look at me!” it growled. Between each phrase it yelled at me, I could hear it’s teeth snapping shut, like a trap that opened to spit curses and closed again. “Señor, you rude piece of shit, you won’t even fucking look at me, shut the fuck up and look at me!” I kept praying and fought the urge to have my vision stray into the seat next to me… but it did, I did not want it to happen but I was seeing so much agitated movement, I could not avoid looking. It was small, but not baby small. It’s limbs were gaunt, not chubby and cherubic. It was coiled like a cat about to pounce. Its features were all gray but it reflected no light so the shadows on it were extremely harsh. Its eyes were just two bottomless holes and finally it’s teeth, the one god damned thing I should have never looked at, were terrifying. Lip less, snarling, framed by swollen and infected gums, they were impossible to miss. Two rows of pointy yellow fangs, with the occasional normal looking tooth in between. They were sharp and deadly, and they were coming at me. I freaked out, I swerved and my car started to spin. I can't explain the physics of it but somehow the thing that was in the air coming for me ended up flying sideways into the back seat, and my car flew off the road. When I awoke I was being pulled out of my upside down vehicle, radio at full blast. I flailed my arms and fought the paramedics who yelled at me to calm down, that I was OK. I mean obviously I was not OK, I ended up in the hospital with a concussion. The police showed up and told me I had fallen asleep at the wheel, and I did not argue with them. My friends and family visited and asked me what happened, so I also told them I had fallen asleep at the wheel. I had no interest in telling people the truth. I had no interest in telling myself the truth. I did not want to think about what happened or plant that seed in anyone else's head. I spent a few extra days at home recovering, working up the courage to go back to work. Then I got a Mexpost from the insurance adjusters. It was a box and an envelope… I opened the envelope first and there was a letter that said, “We were able to recover the following from your car: your registration, a pair of broken sunglasses, one thermos, one rosary, 4 air fresheners, 1 broken animal tooth charm.” I did not know what they meant by an animal tooth charm. I did not want to know. I never opened the box. Instead I submitted my two weeks’ notice and decided to get far away, I went to live with an aunt and uncle across the border. Finding work on a tourist visa was hard. Keeping a low profile when that visa expired was harder. Becoming a US citizen was extra hard. But it was all predictable, a series of milestones on a long straight road. It was the furthest thing from the dark road to Topolobampo with its sudden twists and unexpected turns. I only travel that road in dreams now, and I’ve heard the voice next to me a few times… but it only gets so far as the word Señor and I wake up with my heart pounding. I remind myself that stuff like that does not happen here, I say a prayer, and I try to go back to sleep.  Javier Loustaunau was born in Los Mochis, Sinaloa where he lived until his 21st birthday. Shortly after 9/11 he decided to move to the US to work for a while, taking a break in his studies as a biochemical engineer. Instead he worked his way up from restaurants to banking, from banking to operations and is now a data analyst in the HRIS and Insurance field. He is a published author of poetry and prose, specializing in short scary fiction. You can find his work on the NoSleep podcast and in the anthology Monsters We Forgot.

0 Comments

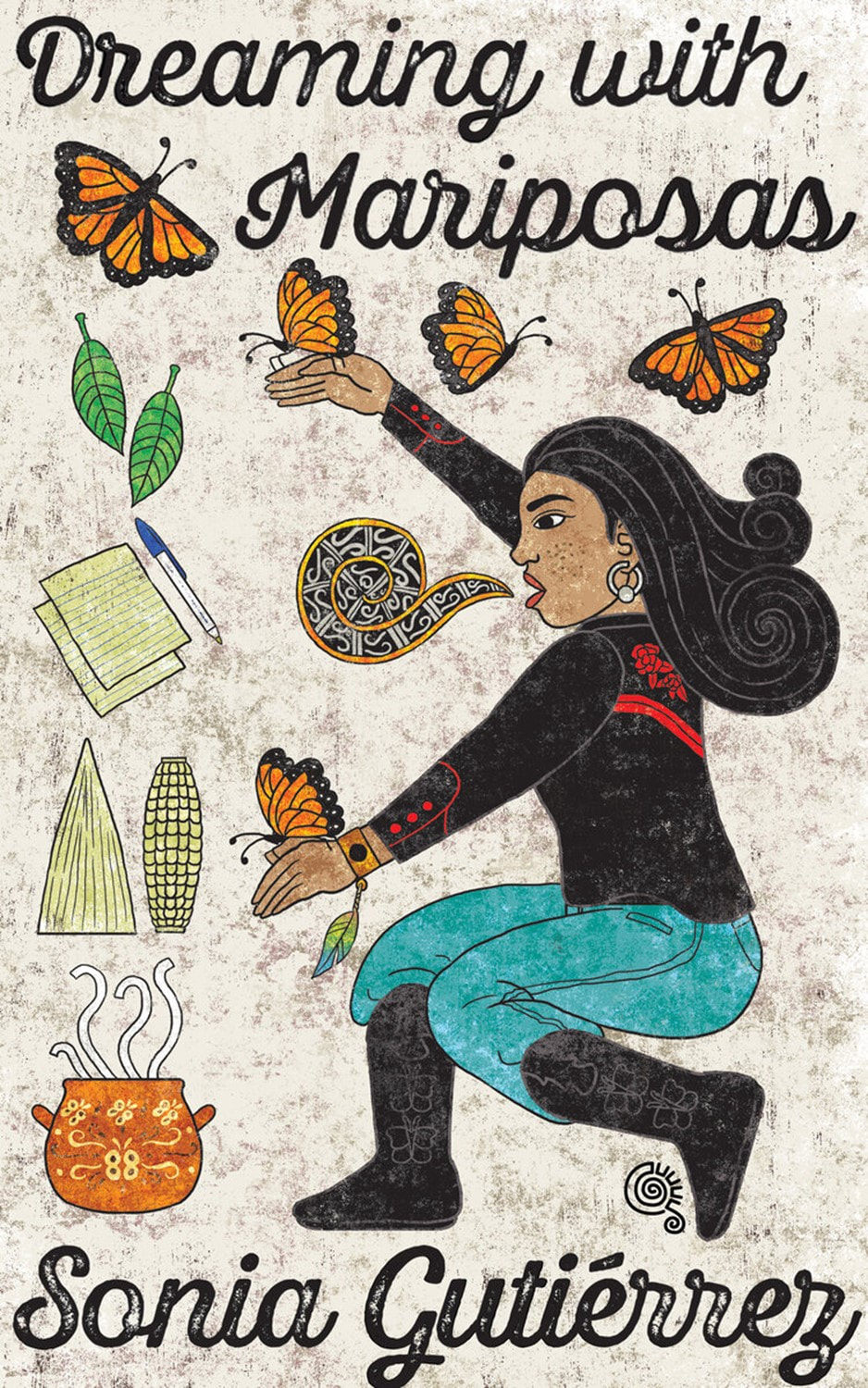

FlowerSong Press in McAllen, Texas, recently published Sonia Gutiérrez's novel, Dreaming with Mariposas, winner of the Tomás Rivera Book Award 2021. Read an excerpt below. Order a copy from FlowerSong Press. Our Doctor Who Lived in Another Country Whenever Paloma, Crucito, and I got so sick Mom couldn’t heal us with her herb-filled cabinets, an egg, or Vaporú, we had to wait for the week to hurry up, so Dad could take us on a trip to visit our doctor who lived in another country. We crossed the border to a familiar place called Tijuana, Baja California, México. Estados Unidos Mexicanos—the United Mexican States—said the large shiny Mexican pesos in Spanish. With her miracle stethoscope, our doctor’s Superwoman eyes and Jesus hands always found where the illness hid. As our father drove into Tijuana, the city looked like an expensive box of crayons. Fuchsia and lime green colors hugged buildings. Dad parked our shiny Monte Carlo the color of caramelo on the third floor of a yellow parking facility, and we walked down a cement staircase and crossed onto Avenida Niños Héroes. Then, we went up peach marble stairs and entered our doctor’s waiting room. On the weekends, patients from faraway cities like Los Ángeles and San Bernardino came to see La Doctora. Judging from the looks of some of the patients’ faces, they were there to see the doctor’s husband, who was a dentist. They made the perfect couple—the doctor and the dentist—for both their Mexican and American patients. The doctor, a tall woman with smoky eye shadow, looked directly into her patients’ eyes when she spoke. Not like some American doctors in the U.S. who didn’t look at Mom because she only spoke Spanish. On one of those doctor visits, I heard the dentist, a tall, burly man with a mustache that looked like a broom, speak English on the telephone with a patient. “John, you need to come in, so I can take a look at your tooth.” Another time I saw an elderly gringo, waiting for his wife, seeking the dentist’s services. That’s when I realized the other side was expensive for them too. When we were done at the doctor’s office, our next stop was El Mercadito on the other side of the block on Calle Benito Juárez. Churros sprinkled with sugar and cinnamon in metal washtubs rested on the shoulders of vendors. Fruit cocktail and corn carts were closer to the sidelines of streets, so passersby could make full stops and buy their favorite pleasure bombs to the taste buds. During summer visits to Tijuana, Paloma ate as much mango as she wanted because fruit was affordable in México. My weakness was corn. And even if I felt sick, I always looked forward to eating a cup of corn topped with butter, grated cheese, lemon, chili powder, and salt. Mexican corn didn’t taste like the sweet corn kernels from a tin can—Mexican corn tasted like elote. Approaching El Mercadito, dazed bees were everywhere. Mother warned us about not harassing bees. Because according to Mom, bees were like us—like butterflies. “Without bees, our world would not be as beautiful and delicious. Bees are sacred, and without them, we wouldn’t exist. Paloma and Chofi, please don’t ever hurt bees,” Mom said as we walked by our fuzzy relatives and nodded in agreement. The smell of camote, cilacayote, cajeta, and cocadas added to the blend of enticing smells at the open market, where we roamed with buzzing bees peacefully. Colorful star piñatas and piñata dolls of El Chavo, La Chilindrina, and Spiderman hung along the tall ceiling, and the familiar smell of queso seco filled the air heavy with delight. Wooden spoons, cazos made of copper, molcajetes, loterias, pinto beans, Peruvian beans, and tamarindo provided such a wide selection of merchandise vendors didn’t have to fight over customers. Politely, they asked, “What can I give you?” or “How much can I give you?” as we walked by. In Tijuana, street vendors sold homemade remedies for just about anything imaginable. “This cream here will alleviate the itch that doesn’t let your feet rest,” and “For a urine infection, drink this tea,” vendors hollered. And then there were the funny concoctions, for which even I, a girl my age, didn’t believe their miracle powers: “For the loss of hair, use this cream that comes all the way from the Amazon Islands.” Hand in hand with our familia, Paloma and I walked the streets of Tijuana with our sandwich bag full of pennies and nickels. We gave our change to children who extended their little palms up in the air. Mom would take a bag full of clothing and find someone to give it to, which I never understood, because most people on the streets dressed just like us, from the pharmacists to children wearing school uniforms. Once, when we were walking in Tijuana, Paloma and I saw a man with no legs riding what looked like a man-made skateboard instead of a wheelchair. Our eyes agreed; the man needed the rest of our change. Besides the rumors about Tijuana being a dangerous place, nothing ever happened to our car or Mom’s purse. In Tijuana, doctors had saved Crucito’s life because my parents knew, if they took Crucito to a hospital in the U.S., he might not come out alive because American doctors wouldn’t try hard enough for a little brown baby like my little brother. In Tijuana, our parents spoiled us with goodies and haircuts at the beauty salon. And I felt bad for Americans who couldn’t afford a doctor and didn’t have a good doctor or a dentist like ours in El Otro Lado—on the Mexican side. Pobrecitos gringos. Launderland “. . . Girls--to do the dishes Girls--to clean up my room Girls--to do the laundry Girls--and in the bathroom . . .” —The Beastie Boys, “Girls” Because we couldn’t afford a fancy steam iron, Mom was very practical. Instead of using a plastic spray bottle, she sprayed Dad’s dress shirts, including other garments with her mouth. She gracefully spat on each garment lying on el burro. Ironing was always an all-nighter that seemed endless and agonizing. I hated ironing Dad’s Sunday dress shirts—or anything, requiring special care and Mom’s supervisory instructions. There were two chores I hated most about being a girl: ironing and washing someone else’s clothes. The piles and piles of Dad and Mom’s dress clothes on top of our clothes seemed endless. (Thank God Father worked in construction or else long sleeve dress shirts would have added more to the pile). As soon as Mom started setting up el burro—the ironing board—in what should have been half a dining room, but instead we used as a bedroom, I began my whining. “Mom, but why do Paloma and I have to iron Dad’s clothes?” “¡Ay Sofia! You’re so lazy!” “It’s just that I don’t understand. I don’t wear Dad’s clothes. Why us?” “Sofia, are you going to start? That mouth! ¡No seas tan preguntona! You always ask too many questions! You always talk back! That tongue of yours. Where did you learn those ways‽” When I nagged, my mother’s facial gestures expressed her disappointment, and she turned her face away from me. What had she done to deserve such a lazy daughter like myself? With a cold bitter laugh, Mom responded, “Because he’s your father,” which I never understood. Having to live in apartments also meant we needed to fight over laundromat visitation rights. If anybody left their clothing unattended and the dryer or washer cycle ended, Paloma had to spy to check if anyone was coming, and I’d quickly take out the clothing and place it on a folding table. I’d throw our clothes inside the washer or dryer, and then we’d run to our apartment; otherwise, we’d be washing and drying all day. When we moved from Vista to San Marcos, that’s when I noticed chores strategically favored the man in our family. For instance, we girls never carried out the trash like Dad—just heavy laundry baskets mounted with dirty clothes. To me, mowing the lawn didn’t look difficult at all. It looked super easy and fun. How to Mow the Long Green Grass By Chofi Martinez 1) Check the lawn for Crucito’s toys, Dad’s nails, and any other sharp objects, including rocks. 2) Add gasoline. 3) Turn the lawn mower’s switch ON. 4) Press on the red jelly like button several times. 5) Pull the starter a couple of times. 6) Push the lawn mower with all your human strength. If I could mow the lawn like a boy, at least I could be outside and listen to the singsong of finches, watch white butterflies flutter through the garden, greet and wave at neighbors passing by, and stare at the endless blue sky. But instead of Paloma and me mowing the lawn, Dad dropped us off at the laundromat on Mission Avenue next to the dairy to wash and fold everything from heavy king-sized Korean blankets to Dad’s dirty and not so white underwear. Bras and underwear were the most embarrassing garments to dry, especially when red stained or not so new underwear fell to the ground, while we checked the clothes in the dryer. If an undergarment accidentally fell, it’s not like we could ignore it and just leave it there when it was clear we were watching each other. For us, if someone looked at our bra or underwear, it was as if they were looking at our naked bodies. It was equivalent to watching feminine hygiene commercials in front of boys or even worse—Dad. Oh my God! ¡Trágame tierra! Sometimes, when we barely had enough quarters and single dollar bills to spare in our imitation Ziploc bag, I’d window shop at the vending machine with its snacks and cigarettes then stare and admire the package labels with the bright oranges and mustardy yellows. While we waited for the washer to end, we sat on the orange laundromat chairs (bolted to the ground in case anyone tried to steal them, I figured). My eyes wandered—at the graffiti, the announcements, the tile floor that needed a broom and a mop, the Spanish newspapers with the sexy ladies with their back to the readers wearing a two piece—a thong and high heels and the constant drop off and pick up of wives and daughters. Swinging my feet back and forth out of boredom, I stared at the dryer’s circular-glass door with the thick-black trim, where garments would slowly go round and round and round and round, painting a picture of a vanilla and chocolate ice cream swirl, which was like meditating in front of a TV screen. Another dryer gave form to a motley of colors from the palette of Matisse’s bright yellows, blacks, oranges and greens Ms. Watson, my art teacher, had lectured on. And then, the dryer came to a full stop, and the colors—the burgundy red and thorny pink roses and the stoic lion—on heavy blankets took their true forms in need of folding. Our Dream Home Mom and Dad were always working for our dream house. In his early twenties, dressed in slacks and a tie, José Armando, our real estate agent, came to our apartment and talked to my parents about becoming homeowners. He sat patiently for what felt like hours translating endless paperwork. José Armando, Tijuana born with Sinaloa roots, grew up in Carlsbad, “Carlos Malos.” He smelled like a professional, and the heaviness of his cologne and starchy clothes filled our small kitchen and living room long after he was gone. Our real estate agent felt like familia. “Helena and Francisco, the contract states that if you complete all the renovations within a year, the bank will approve the loan. You can move in now, but the house is not in living conditions.” “But Jose Armando, I’m sure you’ve heard stories--what if the gringo doesn’t keep his promise?” Mom asked our real estate agent. “Helena, please trust me. Mr. Stoddard is a good man and will not back out of the deal because he signed the contract,” José Armando assured Mom the owner would follow through. “You know Francisco more than I do. Your husband is going to make the house look like a palace—like your dream home. Helena, the property even has a water well. You can add the roses, calla lilies, and fruit trees you’re looking for in a property. And, most importantly, you won’t have to commute from Vista to San Marcos anymore.” Where Dad and Mom came from, waiting periods to build a house didn’t exist; people didn’t need permits to build a home made from adobe or blocks. In the U.S., however, my parents had to settle for a fixer-upper Dad could mend in no time with the help of family and friends. When José Armando finally struck a deal with the owner, it took Dad a whole year to claim the house on 368 West San Marcos Boulevard as our own. After Dad came home from working construction all day, he’d work at home. Mom must have had sleepless nights when Father agreed to buy our first house. That’s because Mother didn’t see what Father saw. We would have a street number to ourselves, 368. The first days at 368, Mom refused to eat in the kitchen, and how could she eat in there? How could her children eat in that thing Dad called kitchen? Yes, the house included a small stove, but cockroaches were baking their own feasts in the oven. Dad imagined a swing set for Crucito in the backyard’s green lawn. But Mother had heard the neighbors walking by say the backyard turned into a swamp during the rainy seasons. Dad imagined a one-foot swallow lined with miniature plants that would keep the water moving to the large apartment complex next door. But Mom saw the swamp at our feet. Dad imagined the pantry and mom’s new wooden cupboards. But Mom saw mice and cockroaches. Lots of cockroaches. Mom saw the faded dilapidated and peeling mint green paint. Dad saw a new wooden exterior and a fresh coat of paint. Our new but old kitchen was infested with silky brown cockroaches—the thin kind that matched the plywood. Underneath the crawl space lived the critters, and at night, big roaches squeezed and welcomed themselves in through both the front and back door to drink water and eat crumbs. Paloma and I, in our superhero capes, made from black trash bags, became Las Cucaracha Warriors de la Noche and ran after the cucaracha bandits. We routinely turned off the lights, and then at about ten o’clockish, Mom turned on the kitchen lights, and Paloma and I charged at them. While they scattered everywhere, we all took our turns killing the horde of nightly visitors. The pest problem at 368 went away with endless nights of Raid attacks and hot water splashing. Paloma and I even conquered our cockroach phobia and squished cockroaches with our very own index fingers. The master bedroom had seven layers of dusty carpets pancaked on top of each other. The wooden floor in our living room held itself together miraculously—we were always careful to wear shoes to prevent any splinters from pricking our bare feet. When we finally settled into our new home, one Saturday morning Paloma and I still in our pajamas were arguing over who would have to sweep and mop before our parents got home from work when suddenly we found ourselves shoving and wrestling each other. And then with a big push, the unexpected happened. I flew through the wall. “Oh my God, Chofi! Look what you did!” “Look what I did? You pushed me, Mensa!” Paloma and I had to reconcile immediately to cover up the crime scene. When Dad got home later that afternoon and walked through the hallway to inspect our chores, he demanded an explanation, “¿Y este pinche sofá? ¿Qué está haciendo aquí?” Chanfles, we thought as our eyes placed the blame on each other. Dad gave us the mean Martinez Castillo stare with the white of his eyes showing that always worked, shook his head, and stormed out of the house because Dad knew he had to replace all the house’s old plywood with new drywall. Our idea of placing a love seat in front of the hole to cover it up didn’t work. Our fear for our father’s punishment turned into giggles and then uncontrollable laughter. Poking at each other’s ribs and yelling at each other, “It’s your fault!” and “No, it’s your fault!” we almost peed our underwear. We laughed at the hole in the wall, the sofa that barely fit in the hallway that must have looked ridiculously out of place in our father’s eyes, and at our new but old house facing the boulevard. Strangers driving by honked or waved and gave Dad a thumbs up when he worked on our house on the weekends. We were living in Father’s dream home, and we were happy. José Armando, our real estate agent, was right—Dad fixed our house, and Mother created her garden of dreams, where Dad and Mom planted hierbas santas. Orange, avocado, peach, cherimoya, guava, and purple fig trees. And native yellow-orange, deep-purple, and rose-colored milkweeds for our butterfly relatives who passed by and travelled south to Michoacán, our parents’ homeland. One day we would follow them if Mom and Dad worked hard and saved enough money. One day. The Guayaba Tree In San Marcos, our backyard smelled like Idaho. The familiar smell of manure from the Hollandia Dairy on Mission Avenue lingered in our backyard. Months before the guava tree joined us at San Marcos Boulevard, Mom took free manure from the dairy for our garden and prepared the earth with water. Even if we already had a few trees, Dad and Mom talked about the trees and plants with special powers that would join our family. Next to the guayaba tree’s new home, the apricot tree had already joined us, and now it was the guava tree’s turn to step out of its black plastic container and to spread its roots and branches. At the end of the week with their Friday paycheck, Mom and Dad’s eyes were set on an árbol de guayaba. Right after work Dad drove us to the northside of San Marcos on the winding road to Los Arboleros, the tree growers’ ranch on East Twin Oaks Valley Road, to buy the perfect tree for our backyard. As we approached a dirt road leading to the Santiago property, Don José in his sombrero and red and yellow Mexican bandana tied around his neck waved at us. At his side, two large Mexican wolfdogs with imposing orange eyes barked at us as we approached the nursery next to their house. “Paloma and Chofi, be careful with Don Jose’s dogs.” “Okay Ma,” we answered in unison. “Buenas tardes, Francisco and Helena. Don’t worry, Señora Helena. My calupohs don’t bite unless they smell evil. They scare off the coyotes that want to get into the chicken coop. Last week a red-shouldered hawk snatched one of my María’s chickens in broad daylight.” Don José’s dogs, Yolotl and Yolotzin, sniffed our stiff bodies while I prayed to San Jorge Bendito: “San Jorge Bendito, amarra tus animalitos . . . .” Yolonzin sniffed and licked my hand. Thankfully, Don José’s calupohs remembered us; we were in the clear. “If you need anything, holler at me. I’m going to water the foxtail palm trees on the other side.” At Don José and Doña María de la Luz Santiago’s small ranch, Paloma and I were careful not to step on rattlesnakes. We walked through the rows of small trees in 15″ containers and played with sticks next to a large flat boulder with smooth holes. I filled the holes with dead leaves and dirt and mixed it with a stick. “Paloma, let’s ask Don Jose about the holes on this large boulder. How do you think these holes got here?” Paloma shrugged her shoulders and signaled with her head to get back. With the calupohs following us, we found Mom and Dad still deciding on a tree and a crimson red climbing rose bush. “But Pancho, look how green the leaves look on this one!” “Yes, Helena, but look at this one. It has a strong tree trunk.” “Pancho, this one has ripe fruit! Smell it, Pancho. With time, this one will be strong too.” “You’re right, Helena. We can take the one you want. Let’s pay Don Jose and get going before it gets too dark, so we can plant our tree today.” “Yes, Pancho, it’s a full moon!” “Paloma and Chofi, I’m glad you’re both back. Go look for Don Jose, and tell him we’re ready to pay.” Paloma and I ran to look for Don José. On our way to find him, I remembered we needed to ask him about the holes on the boulder. “Hola Don Jose. My mom and dad are ready to pay.” “Let’s go then.” “Don Jose, we have a question for you. We saw a big flat rock on your property, and we’re wondering how the holes got there.” Don José cleaned his sweat with his bandana and gave us a pensive look. “Those holes. Well, Chofi, as you may know, this land you see here from Oceanside all the way to Palomar Mountain and beyond was inhabited by Native people. Women sat and pounded acorns on metates like the one you saw and made soup and other foods. You can only imagine how many years it took for those indentations to leave their mark and to withstand time. Those women, Chofi and Paloma, left their mark.” “Oh, wow, Don Jose. That’s why the road is called Twin Oaks Valley Road? It’s a reference to Native people’s trees, who lived in this area?” “Yes, Chofi and Paloma. Native people still live on these lands—in Escondido, San Marcos, Valley Center, Fallbrook, Pala, and Pauma Valley and beyond. Ask your U.S. history teacher about the people who inhabited these lands. I’m sure they can tell you more.” “Thank you, Don Jose. I’ll ask.” Dad and Mom paid Don José, and off we went to plant our guayaba tree. With our guava tree sticking out of the window in the Monte Carlo and lying on Paloma, Crucito, and me in the back seat, Mom was all smiles and kept glancing back. “Pancho, please drive slowly and turn on your emergency lights. Children, hold onto our tree carefully.” “Don’t worry Helena. Two more stop lights, and we’re almost home.” Dad agreed to Mom’s pick because he knew she loved guayabas—all kinds. This time they chose the one with the two guayabas with pink insides, which wasn’t too sweet and just about my height. I preferred the bigger trees at Los Arboleros. Why couldn’t we get bigger trees? Mom and Dad always chose the smaller trees because those were the ones we could afford, and plus we didn’t have a truck like our neighbor Don Cipriano’s, but maybe we could borrow it next time. As soon as we arrived home, Dad cut the container down the middle with a switchblade, and Mom pushed the shovel down with her right foot and split the earth. “¡Ay, ay! ¡Ay Pancho! Be careful with the tree’s roots. Here, grab the shovel. Let me hold onto the arbolito.” Dad dug the hole, exposing the dark brown of the earth as two pink worms shied away from the light. “Dad, can Crucito and me get the worms, pleaseee?” “Hurry up Chofi and Cruz. Go ahead. Your mom and I want to plant the tree today.” “Okay, Apá!” While I carefully took the worms from their home, Mom held the guava tree as if she held a wounded soldier and whispered to the tree, “Arbolito, don’t worry. You’re going to be safe here. I’m going to water you when you get thirsty and take care of you—we all will.” “Pancho, one day we’re going to make agua de guayaba.” “Sí, Helena, we’re going to make guayabate like the one my mom used to make. It was so good!” “I bet it was, Pancho. To prevent a bad cough, my mom used to give us guava tea to fight off the flu.” “Helena, did you know guava leaves are also good for hangovers?” “Ay Pancho. ¿Qué cosas dices? Let’s get this tree planted.” From the dried-up manure pile, Dad mixed the native soil and compost and pulled the weeds. As Mom placed the rootball above the hole, they both looked for the guava tree’s face and centered the tree on top of the hole. With the shovel, Dad poured the dirt around the tree. Mom took the shovel from Dad and pounded softly on the dirt surrounding the guava tree, making sure they left the edge below the surface. Next to the apricot tree with a woody surface, the small guava tree with tough dark green leaves would be heavy with fruit one day for our family, our neighbors, and friends. Dad went looking for a canopy for the young guava tree to protect her from winter’s threatening frostbite, and mom stood in the garden, admiring our new family member. It was time to return the worms to the earth; they were so tender but so strong. I made a little hole with my hand, placed the worms inside, said thank you to the worms, and covered them with dirt. The guayaba tree would make a perfect home.  Sonia Gutiérrez is the author of Spider Woman / La Mujer Araña (Olmeca Press, 2013) and the co-editor for The Writer’s Response (Cengage Learning, 2016). She teaches critical thinking and writing, and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. FlowerSong Press in McAllen, Texas, recently published her novel, Dreaming with Mariposas, winner of the Tomás Rivera Book Award 2021. Her bilingual poetry collection, Paper Birds / Pájaros de papel, is forthcoming in 2022. Presently, she is returning to her manuscript, Sana Sana Colita de Rana, working on her first picture book, The Adventures of a Burrito Flying Saucer, moderating Facebook’s Poets Responding, and teaching in cyberland. El Parbulito |

| Gloria Delgado, born and raised in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, is the daughter of a Mexican father and a Hawaii-born Puerto Rican mother. She and her husband live in Albany, California. One of her stories, “Savanna,” was included in the Berkeley Community Memoir Project’s recently published collection, “A Wiggle and a Prayer.” This is her fourth story for “Somos en escrito.” |

**Painting of San Antonio de Padua, patron of the poor, by Micaela Martinez DuCasse, the daughter of Xavier Martinez, a well-known Mexican artist who spent much of his life in California. Ducasse also taught classes at Lone Mountain when Delgado was a student.

This story is a work of fiction based on historically documented events. All individuals with surnames, including their children, were real people; those without surnames are fictional.

In Mexico tens of thousands of residents, Indians, mestizos and españoles alike, died from intermittent plagues, smallpox, chickenpox, mumps and measles. At times there were so many deaths that the priests were too overwhelmed to comply with church regulations as to the proper listing of entries in the death records, able to note only the date of death and the names, if known, of victims who were interred on that date.

Don Augustín Diaz-De Leon’s child, Pantaleón, died in December 1747, eight months after the death of his father. Pantaleón was three years old. The youngest child, Augustín Miguel Estanislao, was born two weeks after his father’s death, on 11 May 1747. He survived into adulthood, eventually settling in Sierra de Pinos, Zacatecas, where he and Thadea Josepha Gertrudis Muñoz Tiscareño married.

Don Augustín’s widow, doña Maria Antonia Fernandez de Palos Ruiz de Escamilla and el alcalde mayor don Fernando Manuel Monrroy y Carrillo, (witness to the death of don Augustín as well as the executor of his estate) in September 1749 were granted a dispensation to marry. Don Fernando was a widower; his first wife was doña Juana Salvadora Jimenez.

Don Augustín’s father, el alférez (subaltern) don Visente Xabier Diaz-De Leon, was at this time the owner of the Hacienda de Peñuelas. Following the death of his first wife, doña Catharina Acosta, he married and raised another family with his second wife doña María Dolores Medina. Upon his death in April 1754 he left money (including 15 gold Castilian ducats) for his intentions, including 100 masses to be offered for the repose of his soul and for his servants, living or dead.

The ex-Hacienda de Peñuelas, still in existence, is one of the oldest haciendas in the Mexican state of Aguascalientes. Established sometime before 1575, Peñuelas predates the foundation of the Villa of Aguascalientes itself. This hacienda consisted of several self-supporting plantation-like communities staffed and farmed by resident Indians and slaves.

The Cathedral Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, originally known as San Ysidro Labrador, was initiated in 1704 and completed in 1738 by don Manuel Colón de Larreátegui, head of the Mitra de Guadalajara. Its northern bell tower was completed in 1764, the southern bell tower not until 1946.

Sources

All birth and death documents cited are from the following:

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints:

FamilySearch.com and other films on line.

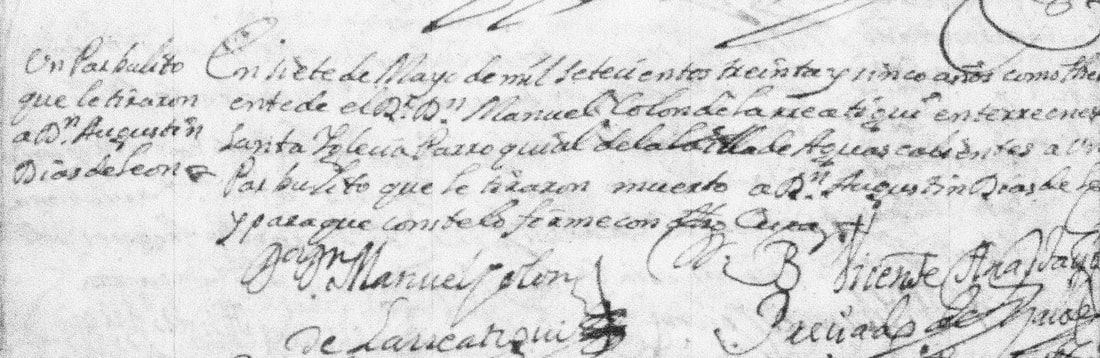

The entry cited re the infant, the parbulito of this story, is from:

Mexico Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, Catholic Church Records

Parroquia del Sagrario, Asunción de Maria

Defunciones 1708-1735, 1736-1748

El Parbulito: Image 530 [Libro quatro de Entierros]

Montejano Hilton, Maria de la Luz:

Sagrada Mitra de Guadalajara, Antiguo Obispado de la Nueva Galicia, 1999

Rojas, Beatriz, et al:

Breve historia de Aguascalientes, 1994

Topete del Valle, Alexandro:

Aguascalientes: Guia para visitar la Ciudad y el Estado, 1973

Vázquez y Rodríguez de Frias, José Luis:

Genealogía de Nochistlán Antiguo Reino de la Nueva Galicia en el Siglo XVII según sus Archivos Parroquiales, 2001

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

April 2024

March 2024

November 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

December 2021

November 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

December 2020

September 2020

July 2020

November 2019

September 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

February 2010

Categories

All

Archive

Aztec

Aztlan

Barrio

Bilingualism

Borderlands

Boricua / Puerto Rican

Brujas

California

Chicanismo

Chicano/a/x

ChupaCabra

Colombian

Colonialism

Contest

Contest Winners

Crime

Cuba

Cuban American

Cuento

Cultura

Culture

Curanderismo

Death

Detective Novel

Día De Muertos

Dominican

Ebooks

El Salvador

Español

Español & English

Excerpt

Extra Fiction

Extra Fiction Contest

Fable

Family

Fantasy

Farmworkers

Fiction

First Publication

Flash Fiction

Genre

Guatemalan American

Hispano

Historical Fiction

History

Horror

Human Rights

Humor

Immigration

Indigenous

Inglespañol

Joaquin Murrieta

La Frontera

La Llorona

Latino Scifi

Los Angeles

Magical Realism

Mature

Mexican American

Mexico

Migration

Music

Mystery

Mythology

New Mexico

New Mexico History

Nicaraguan American

Novel

Novel In Progress

Novella

Penitentes

Peruvian American

Pets

Puerto Rico

Racism

Religion

Review

Romance

Romantico

Scifi

Sci Fi

Serial

Short Story

Southwest

Tainofuturism

Texas

Tommy Villalobos

Trauma

Women

Writing

Young Writers

Zoot Suits

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed