|

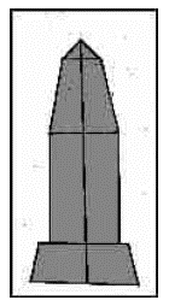

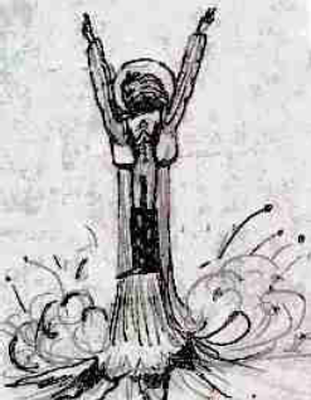

The Oñate Expedition’s Mysterious Encounter with a “Demon”, as Recorded by Capitán Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá in 1610 By Louis F. Serna, with sketches by the author When Cortez first saw the Aztecs and their magnificent city in 1519, he must have marveled at the sight before him! Coming from the then “civilized” country of Spain which was celebrating high prominence among their European neighbors, the Spanish were very conscious of the “style of the nobility”, high fashion, and the literary arts. They saw themselves as far more advanced and civilized than the people they encountered elsewhere, including the Aztecs. They and their European neighbors such as England and France considered themselves highly educated, and entrusted with the self-imposed righteous responsibility of bringing religion to heathens at every known port. With “soul saving” in mind, Spanish sailings included an abundance of Franciscan friars anxious to spread the word of God as emissaries of the Catholic faith and the Pope in Rome. Spanish monks saw themselves as duty bound to teach Christianity to those under-privileged savages they heard of from exploring conquistadores, and they couldn’t wait to have their names immortalized as “crusaders” and even martyrs. Certainly, those Friars would have known of all Spanish explorations of the time and of the many amazing discoveries as the Spanish sailed from port to port, seeing and reporting new places and people still in their primal evolution. As for Cortez, he must have been in awe of those Aztecs, their culture, amazing cities, their gold, and their advanced knowledge of astronomy. And certainly, he would have known all along that he was duty bound to take every ounce of gold they might possess, to enrich his King, Country, and himself. In the process, he almost certainly also knew that he would probably have to kill them all to get it! Thus began the Spanish “entrada” (entrance) into this new land called “Mexica”, “la nueva viscaya”, “la Nueva Espana”, “la Nueva Galicia”, and later to the north, “el Nuevo Mexico” (today New Mexico). Following the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs by Cortez, other notable Spaniards would quickly occupy the lands in the interior of what became Mexico and become rich off of its resources. Spaniards like Cristobal de Oñate, who established himself in the area of Zacatecas, rich in silver ore. He became a very rich man, taking tons of silver from “la Bufa”, that famous mountain some believed was made entirely of silver, and other mines punched into the countryside. By then, in 1540, another adventurous Spaniard by the name of Coronado was already advancing into the area to the north… the area where those Aztecs were said to have come from originally…. The lands where people lived in multi-storied structures made of mud brick and stone… lands that Cabeza de Baca, just a few years earlier, claimed to be rich in gold, and in fact, he said he saw “cities of gold…” Seven of them..!!! As anxious as the Spanish adventurers were, to seek their fortunes up north, they knew and respected the laws of their King, which prevented them from just sauntering up into the frontier lands at their convenience and enriching themselves of what they might find. Special permission, money, and noble class were the prerequisites to any exploration. The King of Spain assured that his “right to his domain” in all explorations was protected, by requiring that the right man be selected for any explorations. A proven leader whose family would be scrutinized by the Viceroy to assure their finances, and then they would have to pass his “inspection.” Preferably, the man would be of noble birth or of royal “order”, and from a well funded family, to assure that he could afford to pay his way, and all the expenses of his expeditionary force. The King risked only a military escort, and that primarily to protect his investment. Such a man would have to take complete responsibility for the success of any expedition and in the event of success he would enjoy titles, lands, and a good share of whatever treasures the lands had to offer. Should he fail, he would lose all his investment, and probably face the King’s penalty tax for failing, as well as disgrace brought on to his family! Who would risk all this? Knowing with some certainty that the lands to the north were probably impoverished, and knowing that the stories of wealth were spun by the deceiver, Cabeza de Baca, as reported by Coronado, and knowing that the reports filed by that earlier Conquistador painted a dismal picture of hardship to the north, the man who dared was Don Juan de Oñate, the son of the wealthy Zacatecas silver merchant, Cristobal de Oñate. Juan was a son, wanting so desperately to equal or better his father’s achievement of having gained such great wealth in the silver mines. He was also desperately anxious to prove to others that he was a manly conqueror and to become the greatest achiever of them all! And so he filed his petition in 1596, and began the process of selection and approval by the King of Spain. Many troubles arose for Oñate in recruiting soldiers, supporters, wagons, food, tools, and hardest of all, the King’s hesitant approval. Finally, three years after he began the process, and at great expense to him as he continued to add colonists and supplies which the horde of people seemed to consume as fast as he acquired it, word came from the King that he was free to start his march. Finally, yet another Spaniard began his search for riches and a fruitful destiny! And he too, would encounter strange people, customs, and an unforgiving land! A byproduct of the Spanish King’s “need to know” of where all his subjects were at any given time, lest he lose out on any taxes due him, was that everything worth knowing be recorded and filed with his Vicero. As well, the Monks, who also sought equal shares of notoriety and taxes to be had, recorded their activities to their superiors and ultimately to the living icon, the Pope in Rome! In view of all this need to record, the leaders of expeditions usually assigned experienced scribes to record all activities of their explorations. That man would also have the confidence and approval of the Crown, so this would be a man of considerable trust and reputation. In addition to his “official” records, “diaries” were also kept by officers, enlisted men, and all concerned. Today, we have a great amount of information about the people, the times, and the wondrous things they encountered, thanks to the printed record of the day-to-day activities of those early Spanish folk.  Capitán Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá Capitán Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá Capitán Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá It is the writings of one of those Oñate Officers, which is the subject of this story. The writer – recorder - author is that well respected scribe, Don Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá, who was made a Capitán in Onate’s staff in 1596. His later titles and accomplishments would be many. His writings have been preserved in several productions, and in particular in a book titled: “Historia de la Nueva Mexico, 1610”. This particular book is considered “A critical and annotated Spanish / English Edition, translated and edited by Miguel Encinias, Alfred Rodriguez, and Joseph P. Sanchez”. The well educated and well read Villagrá wrote his account of events in a Spanish prose / poetry style. He captioned them as “Cantos”, (songs), which are replete with references to the earliest biblical events and writings of scholars of earlier times such as Pliny, Plato, and others. Villagrá can be considered to be a most reliable and learned observer and recorder of his time. And so it is that the scholars of today, such as those mentioned above, took great respect and care in their treatment and interpretations of Villagrá’s Cantos, from Spanish to English. And that is how they appear in the book mentioned: his entry in the Spanish of that time, and alongside, the English interpretation. The Book – Historia de la Nueva Mexico, 1610 Finally, I draw your attention to Villagrá’s first and second Cantos, in which he writes about the mass of humanity that had assembled at or near what is now El Paso, Texas, known then as “el paso del Norte” and by other names. In referencing their interpretations, Encinias, Rodriguez, and Sanchez, are hereafter referred to as: “the interpretors”, and so we begin.  El CANTO PRIMERO Villagrá entitles his Canto Primero, “Que Declara el argumento de la historia y sitio de la nueva Mexico y noticia que della se tuvo en quanto la antiqualla de los indios, y de la salida y decendencia de los verdaderos Mexicanos”. The interpreters’ English version is: “Which sets forth the outline of the history and location of New Mexico, and the reports had of it in the tradition of the Indians, and of the true origin and descent of the Mexicans.” My interpretation: In his first Canto (Canto Primero and Canto I), Villagrá describes the geographical location of the point of beginning of the Oñate Expedition. In his learned way, he carefully references its location, relative to geographical north – south longitude and east – west latitude with the then known points of the compass and even compares the location on the world globe, with known places in the old world. He equates the location geographically, to Jerusalem by latitude! He also describes the mass of humanity that is the expedition, and even marvels at the attire of some of the characters. Some are well-dressed gentlemen, riding excellent mounts adorned with “finery” and “livery as in the finest courts” which clearly defines to their noble class, while others are fearful looking men, one even wearing the skin of a lion complete with mane! Some wear the skins of striped cats, leopards, and even wolf skins! They carry weapons of all sorts, and banners and standards of all colors and kinds as they slowly move along. It is a fearful and bedraggled looking lot! People, cattle, goats, sheep, and everything necessary to support the expedition walk in unison. At the end of Canto I and in Canto II, which is again, the subject of this article and the beginning of Oñate’s drive north, he describes a terrible apparition! It is the last lines of Canto Primero and the text in Canto Segundo that fascinates me. My fascination is in that although I interpret Villagrá’s notations and descriptions of the “apparition” literally in the same way as the interpreters do, I see through Villagrá’s eyes, something quite different and amazing than they do! Being careful not to show disrespect to those interpreters in any way, I claim the right to my own interpretation and understanding of what Villagrá and the whole camp saw and what he recorded so carefully in the only way he knew how. He compared what he saw to things he could relate to at that time in 1599. In Canto I, Villagrá ends his description of the mass of moving people by stating that as the many people (and animals) trod on over the hard baked ground, they raised a huge cloud of dust. Suddenly, a figure appeared before them, which he describes as looking like an old naked woman: “Delante se les puso con cuydado, en figura la vieja desembuelta, un valiente demonio resabido – cuyo feroz semblante no me atrevo, si con algun cuydado he de pintarlo, sin otro nuevo aliento a retratarlo”. The interpreters write: “There placed before himself, before them by intent, is the form of an old and hag-like woman. A valiant and cunning demon, whose face ferocious dare I not look at, if I must with some care depict it, set out to paint without new strength.” My interpretation: It appears that Villagrá and those with him have come face to face with a being, which he says carefully, or cautiously, appears before them, resembling an old naked hag-like woman. (I think he assumes it to be “feminine” as he can see no male genitalia). His first reaction is to associate this inhuman form with some kind of demon or even the devil! It has such terrible features (cuyos feroz semblantes), that he doesn’t dare assume that it is (the devil), as in his next breath (otro nuevo aliento), he may create it in his mind or in fact, create it incarnate (a retratarlo)! So what is this being that suddenly confronts them? Appearing to look like an old, naked hag? Follow up: In modern times, today, his description takes on the appearance of those ugly little beings who we hear and read about, and who appear to wear a one-piece, pale gray, skin-tight garment if any at all, and who we call, Extraterrestrials!!! CANTO SEGUNDO Villagrá writes the Canto Segundo in the first person, as an eyewitness to what he and others are observing. Again, Villagrá entitles Canto Segundo: “Como se apparecio el Demonio a todo el Campo, en figura de vieja y de la traza que tuvo en dividir los dos hermanos, y del gran mojon de hierro que asento para que cada cual connociesse sus estados”. The interpreters’ English version is: "How the Devil appeared in the whole camp in the shape of an old woman, and of the scheme he had to separate the two brothers, and of the great heap of iron that he left so that everyone might know his true estate”. My interpretation: I think that Villagrá has seen what he (and the others) believe is the devil in the disguise of an old hag-like, nude woman. Although terrified, they courageously stand their ground. Somehow, the entity communicates to them, or they believe they hear it say, that it is going to separate the two “brothers?” It also leaves “un gran mojon de hierro que asento para que cada cual connociesse sus estados”. The interpreters say “he left a great heap of iron”. My interpretation of this “heap of iron”, is that Villagrá is describing a one-piece metal vessel, standing upright. A “mojon” in Spanish, can be a landmark… as in a real estate landmark or marker of the boundaries of one’s lands. The landmarks of old were shaped like an obelisk, and in this case, made of metal. Is this the shape that Villagrá is seeing and can only describe it in a familiar term, like a “mojon de hierro?”  The Being’s Vessel Above is an example of a “mojon”. A Spanish word for a landmark or monument, typically used to mark boundaries of property. Typically they are four-sided, hewn from stone, and pointed at the top to prevent snow or water from settling on its top, lest the water turn to ice in winter and crack, and eventually break the stone. The sides are usually oriented to the four directions of the compass and may contain the owner’s name, coat of arms, and/or the geographical extent of that corner or location of the property. The size of landmarks varies, and the height can be as much as one meter. The sides can be one-fourth that, or per the owner’s specifications. Does Villagrá mean that the creature “left” that mojon de hierro (vessel)? As in, coming out of it? And it is therefore his “estate” or “place of residence?” I think Villagrá could be saying that the entity “exited” from an upright metal vessel shaped similar to a “mojon” and came toward them. I do not interpret his use of the word mojon, as a “heap of iron”, which implies a pile of metal scrap. I don’t believe that Villagrá had that meaning in mind. Villagrá next describes the being as: “Delante se les puso aquel maldito, en figura de vieja rebozada. Cuya espantosa y gran desemboltura, daba pavor y miedo imaginaria. Truxo el cabello cano mal compuesto y, cual horrenda y fiera notomia, el rostro descarnado, macilento. De fiera y espantosa catadura: desmesurados pechos, largas tetas, hambrientas, flacas, secas y fruncidas, nerbudos pechos, anchos y espaciosos, con terribles espaldas bien trabadas: Sumidos ojos de color de fuego, disforme boca desde oreja a oreja, por cuyos labios secos, desmedidios, quatro solos colmillos hazia fuera de un largo palmo, corbos se mostraban: los brazos temerarios, pies y piernas por cuyas espantosas coniunturas una ossamenta gruesa rechinaba, de poderosos nerbios vien assida" . The interpreters write: “That accursed one, placed he before them in the form of an old woman well disguised, whose great and fearful cleverness, doth cause both fear and terror to imagine. He had his gray hair badly dressed, and like a horrible, fierce skeleton, his fleshless and emaciated face, of an expression wild and fearsome, misshapen breasts and dangling teats, starved, flaccid, dry, and wrinkled. Great chest, both wide and spacious, with shoulders terrible, well set eyes sunk and colored as of fire, a mouth small formed, from ear to ear, through whose dry and distorted lips, fangs, just four protruded, and showing themselves in good palm’s length. His arms were fearful, feet and legs, in whose fearsome joints the bones creaked loud. Well set, with muscles powerful. Just as they picture for us and do show, The ferocious person of brave Atlas, upon whose great and robust strength, the great incomparable weight and thrust of highest-lifted heavens doth rest.” My interpretation: Generally, I agree with the literal interpretation of the interpreters, but I feel that looking at the entity through Villagrá’s’ eyes, he sees a living being, with a very small, thin body on the one hand, (desmesurados pechos, largas tetas, hambrientas, flacas, secas, y fruncidas), yet with very broad shoulders bien tradadas, which in Spanish, can mean “shoulders with a brace or apparatus connected to them, or over them, making them look larger than they are”. (Example: in Spanish, un buey tradado, means an oxen with an ox yolk over his neck and shoulders, which can be quite massive).  The Being’s Bodily Appearance Can this mean it was wearing something on or over its shoulders? Like a life support pack of some kind? Villagrá then says he could see “los brazos temerarios, pies y piernas por cuyas espantosas conjunturas, una ossamente gruesa rechinaba” Could this mean the being’s arms were such that Villagrá did not feel they were arms but were exaggerations of arms? Temerarios means overly bold or inconsiderate, or baseless. Perhaps that is how he saw the arms… covered with something that made them look bigger than arms should be? Pies y piernas por cuyas espantosas conjunturas. Villagrá describes the arms and legs as frightening in that the legs seem to be joined or connected to each other, as one… (conjunturas) Could they be covered with some kind of protective clothing or apparatus? Could the being be standing in some kind of apparatus that partially covers his feet and legs? He says that “una ossamente gruesa rechinaba”. He says that one of the “boney” legs or both as one, made a loud creaking, screeching, or whining sound, Could this be the high pitch sound of a propulsion device? Or propelled device on its legs or whatever Villagrá saw and describes as legs joined together? As if to confirm this thought, Villagrá adds to the description of the “legs”, “de poderosos nerbios vien assida”. Could the “powerful nerves, well constructed”, he is describing, be in reality, hydraulic-like tubes or lines attached to the being’s legs, or whatever he is standing on? Can we see through Villagrá’s eyes, in his description, a very frail like being, ugly to them like an old skinny, nude, woman would look, but partially “clothed” in a suit of some kind that has some kind of apparatus on or over its shoulders, and some kind of leggings or apparatus with fluid-like lines attached, that make a whining sound like a motor would make? The Being’s Head Villagrá then describes the appearance of the being’s head: “Encima de la fuerte y gran cabeza, un grave, inorme, passo, casi en forma de concha de tortuga lebantada, que ochocientos quintales excedia, de hierro bien mazizo y amasado.” The Interpreters write: “Upon her head, so great and strong, a huge, enormous weight, almost in the form a tortoise-shell set upright, exceeding some eight hundred quintal weight, of metal, massive and well molded".  My interpretation: Again, I agree with the literal interpretation that the interpreters say Villagrá saw, and would add that again, looking through Villagrá’s eyes in that time, he could only compare what he saw to something he knew, yet ridiculous…a tortoise shell over the being’s head! If Villagrá were living in modern times, he could easily say that the being was wearing a large, shiny clear acrylic helmet, almost exactly like our astronauts wear today. Villagrá next writes: “Y luego que llego al forastero campo y le tuvo attento y bien suspenso, con lebantada voz desenfadada, herguida la cerviz, assi les dijo: “No me pesa esforzados Mexicanos, que como bravo fuego no domado. Que para su alta cumbre se lebanta no menos seays movidos y llamados de aquella brava alteza y gallardia de vuestra insigne, ilustre y noble sangre, a cuya heroica, real, naturaleza, le es propio y natural el gran deseo. Con que alargando os vais del patrio nido, para solo buscar remotas tierras, nuevos mundos, tambien nuevas estrellas, donde pueda mostrarse la grandeza de vuestros fuertes brazos belicosos, ensanchando por una y otra parte, etc.” The interpreters write: “And when he came upon the foreign camp, holding it attentive and in suspense, with a loud voice and unembarrassed, his head erect, he then addressed them thus: “I am not pained, o valiant Mexicans, because, as raging fire never quenched, which rises to its summit high, you are in no way less moved or beckoned by the rude haughtiness and gallantry of your illustrious, grand, and noble blood, to whose heroic royal character is natural, inborn, this great desire, with which you go from the paternal nest, only to seek for lands remote, etc., etc.” My interpretation: It seems that in this lengthy passage, Villagrá writes that the being confronts the very attentive people in camp and speaks to them, telling them that it understands how they feel, compelled to enter new lands and that it is in their nature to do so, given their royal blood, etc…. It seems that suddenly, Villagrá no longer fears or sees the entity as an ugly devil, but now it speaks to them in an understanding tone of voice, empathetic to their cause, agreeing with their right to pursue their search for new lands, etc. Or is Villagrá now writing for the eyes of the King? Or his representative, the Viceroy? Perhaps not wanting to appear less manly for previously being afraid of this being? Did the being really say these things to them? Why would it now seem to agree and invite them to continue into this new land, when at first it seemed so threatening? Villagrá next writes: “Y lebantando en alto los talones, sobre las fuertes puntas afirmada, alzo los flacos brazos poderosos, y dando al monstruosa carga buelo, assi como si fuera fiero yrayo, que con grande pavor y pasmo assombra, a muchos y los dexa sin sentido” The interpreters write: “And raising from the ground his heels, set firm upon his mighty toes, he raised his powerful, mighty arms and giving to his monstrous load a push, as though it were a mighty thunderbolt.”  My interpretation: Villagrá describes a being rising off the very ground, by some “force” emitting from its feet. It raises its spindly, but powerful arms and “lifts” its bulky body, (el monstruosa carga buelo), like a metallic bolt of lighting, leaving them stunned and senseless! Villagrá earlier described a heavy bulky suit over a spindly body. Now he sees the small but heavy being lift off the ground with bolts of lightning emanating from his “feet”. Could the bolts of lightning be exhaust from some kind of propulsion unit? He describes it as best he can. Villagrá next writes: “Assi, con subito rumor y estruendo, la portentosa carga solto en vago y apenas ocupo la dura tierra quando temblando y toda estremecida, quedo por todas partes quebrantada!” The interpreters write: “So with a sudden and horrendous noise, he threw aside the mighty load. And hardly did it strike the flinty earth, when, trembling and shaking all, that earth was broken everywhere.” My interpretation: Villagrá describes as best he can, how as soon as the entity clears his “feet” off the ground, there is a mighty roar which makes the earth tremble and the ground below the entity is blown away in all directions… just like a modern day astronaut blasts off with a shoulder mounted jet-pack, like those presently being tested by our military, and even demonstrated at an NFL football game on one occasion, when the pilot flew all around and over the grandstand spectators! Villagrá continues: “Y assi como acabo, qual diestra Circe, alli desvanecio sin que la viesen, senalando del uno al otro polo. Las dos altas coronas lebantadas. Y como aquellos Griegos y Romanos quando el famoso Imperio didieron, Cuio hecho grandioso y admirable.” The interpreters write: “And when ‘twas done, like Circe skilled, he vanished thence without their seeing him, pointing to one and to the other pole. The two crowns raised on high, just as the Greeks and Romans when they divided the empire famed.” Villagrá continues: “Tan presto como viene, bemos buelve, assi con fuerte bote, el campo herido con lo que assi la vieja les propuso, la retaguardia toda dio la buelta para la dulve patria que dexaban”. My interpretation: Again Villagrá describes what he sees and can only compare it to a great event he knows of: the parting of the Greek and Roman Empire! He sees the being rise and fly back and forth from north to south, (the poles), and as quickly as it goes, it returns, and he sees “las dos altas coronas lebantadas”. He must be seeing the “burst” of flames or exhaust from two jets attached to the back pack the entity is wearing. which to him, from below, look like two shining royal “crowns” glittering up high. The interpreters write: “ Thus in a bound, the stricken camp became from what the woman had proposed to them, all the rear guard did turn again toward that sweet fatherland they’d left”. My interpretation: Villagrá now sees the frightened people in the camp, terrified at the sight of the being flying overhead, to and fro, beginning to turn around and beginning to retreat back to the safety of whence they came. Villagrá now writes, as though a day or more later: “Y por sus mismos propios ojos viendo la grandeza del monstuo que alli estaba. Al qual no se acercaban los caballos por mas que los hijares les rompian, porque unos se empinaban y arbolaban con notables bufidos y ronquidos, y otros, mas espandados, resurrian por uno y otro lado rezelosos de aquel inorme peso nunca visto, hasta que cierto religioso un dia celebro el gran misterio sacrosanto de aquella redencion del universo, tomando por altar al mismo hierro, y donde entonces vemos que se llegan sin ningún pavor, miedo ni reselo a su estalage…” The interpreters write: “There still remains in the same way, the mighty mass which there was placed, in height some twenty-seven degrees and a half more. And there was no man of all your camp who did not stop, astonished, stunned, and almost senseless, considering that same story and seeing with his own two eyes the greatness of the monstrous mass was there. And of the horses, not one would approach it unless one tore their flanks, for some stood on their hind legs, rebellious, with whistling, and snorts, and others, frightened more, did shy suspicious from one side to the other from that enormous mass, such as was never seen. Until one day a certain priest did celebrate the great most holy mystery of that redemption of the universe, taking for altar that same mass of iron, and ever since we noticed that those beasts came without fear or trembling or suspicion to it’s foot”. My interpretation: Villagrá now writes about a huge metal vessel or ship, which now stands in the place where the previous apparitions were witnessed. It rests upright and he measures it in degrees of an angle, instead of measurement of height. Can this mean that the top of the vessel is angularly shaped? Cone-like, as like a present-day missile? And like the mojon described earlier? He says anyone (everyone), from the camp now comes to see it in complete disbelief and amazement. The horses sense something very foreign as they display terrified behavior, rearing up on hind legs and refusing to come closer. Then Villagrá says “a certain priest celebrates a most holy mystery of that redemption of the universe, using the base of the vessel as an altar, and all seems calmed with the animals”. Is the “certain priest” an entity from the vessel? If it is one of the monks among the Spanish, why doesn’t he say it is a monk? And the “celebration of the most holy mystery of the universe”, at the base of the vessel. Is the entity simply disconnecting something or turning something off at the base of the vessel? Such as a motor, which is making high frequency waves, which scare the animals? Does Villagrá mistake his actions as some kind of religious ceremony he is conducting? Villagrá describes it as best he can, when he writes: “and ever since we noticed that those beasts came, (the horses), without fear or trembling or suspicion, right to it’s foot, as to a place which has been freed from some unloosed infernal fury”. It seems that after the “priest” did whatever he did at the base of the vessel, the horses no longer fear it. Note that Villagrá and the people in camp no longer refer to the entity as a devil, witch, or brujo; they now seem to accept that what they have been seeing as something wondrous is apparently harmless to them as they freely come to see and touch the vessel. Villagrá writes perhaps the most telling account of what the “heap of iron” is: “Y como quien de vista es buen testigo, digo que es un metal tan puro y liso y tan limpio de orin como si fuera una refina plata de Copella”. He further describes the purity of the metal, and can only wonder how it could have been created in that primitive land, not understanding that it probably came from beyond our world." The interpreters write: “And I as one who is good witness of that sight, say that it is as pure and smooth a metal, and free of rust, as if it were silver refined at Copella!” My interpretation: Villagrá’s’ description of the vessel’s metal surface speaks for itself. For me, the description is very familiar. For many years, I worked as a machinist and welder for the Boeing Aerospace Company in Seattle, Washington. I taught metallurgy, welding, and fabrication in several Community Colleges in that City for many years. I also worked in an Engineering office designing pressure vessels using various state of the art exotic metals, some that can withstand rust, abrasion, and acids, and remain highly polished. The metal Villagrá describes can only be a highly polished alloy, not of this earth, especially in that day and age. Villagrá now wonders as to the construction of this “mojon” which is in fact, a wondrous craft: “Una refina plata de Copella, y lo que mas admira nuestro caso, es que no vemos genero de veta, horrumbre, quemazon, o alguna piedra con quia fuerza muestre y nos pareca aberse el gran mojon alli criado, porque no muestra mas señal de aquesto, que el rastro que las prestas aves dejan, rompiendo por el aire sus caminos, o por ancho mar los sueltos pezes quando las aguas claras van cruzando..!” The interpreters write: “And what our people wondered most, is that we saw no sort of vein, nor scoria, trace, nor any rock, by means of which we might be shown or see how the great mass could be created there. Because there is no more trace of that, than the swift birds leave traces in the air through which they make their road, or, in the sea, the swimming fish, when they go plying through the waters clean”. My interpretation: Villagrá, again is trying to compare this wondrous metal to something familiar, as he and the others contemplate what he now calls “una refina plata de Copella”, “the finest silver from Copella”, and no longer “un monton de hierro”, “a heap of iron.” He and the others can’t understand how this vessel was constructed. It has no apparent rivets, joints, or seams, (genero de veta), there is no evidence of metal casting materials like sand or clay in evidence, (horrumbre), nor evidence of a smelting fire or oven, (quemazon) where it may have been cast. There is not even a rock with which someone might have pounded the mass into shape. Understandably, they assume someone built the vessel where it stands, as the concept of it having flown there is not a consideration. He goes on to write that there is no trace of its fabrication anywhere, just as one doesn’t see the “trace” or track of a bird flying through the air, or the “trace” or track of a fish swimming through the cleanest water. He is obviously in awe of this mystery. Villagrá next writes that there were stories told by the “antiguos naturales”, the ancient native Indians of the old tribes of Mexico, of people from the far off northland from whom they say they are descended. These people were “como en Castilla, gente blanca, que todas son grandezas que nos fuerzan a derribar por tierra las columnas del “non Plus Ultra”, infame que lebantan Gentes mas para rueca y el estrado”. People who looked as white as those of Castille, of grandeur, just as our memories of those beyond the columns of “Non Plus Ultra”, who were famous for their ability to elevate themselves on platforms! This appears to be a reference to the ancient people of Atlantis, who Villagrá knew of from Pliny and Plato’s writings, and who were said to live beyond the columns or pillars of Non Plus Ultra, (the Straits of Gibraltor.) “The place no one dares go beyond,” where the inhabitants, (Atlantians), (Gentes mas para rueca), were said to elevate themselves on “platforms” (estrados). Finally, at the end of Canto Segundo, Villagrá writes, in reference to the people encountered: “Mas dexamos aquesta causa en vanda, cerrando nuestro canto mal cantado, con aber entonado todo aquello, que de los mas antiguos naturales ha podido alcanzarse y descubrirse”. The interpreters write: But let us lay this thing aside, which needs a story long to tell it all, closing our Canto, badly sung, by having sung quite all of what, by the most ancient natives here, could be remembered and discovered, about the ancient descent. My interpretation: Frustrated, Villagrá writes, “let us lay this event aside, which needs a story long to tell it all.” Obviously, he has seen much he cannot explain and feels it is a story too long to tell to make sense of it, and perhaps because the expedition is now moving on, and he decides to put this experience aside. He says his Canto is “badly sung,” meaning he is obviously disappointed that he could not better explain in words, all he has seen and all he has experienced, that he cannot explain it all as he doesn’t have the experience or memory to relate to, as this is all new to him…. He seems to writes it off as if to say, “Ask the natives… they can tell you more from their memories of their ancient ancestors!” Villagrá ends the Canto Primero with these final words: “De aqueste nuevo Mundo que inquirimos, adelante diremos quales fueron y quienes pretendieron la jornada sin verla en punto puesta y acabada”. The interpreters write: Of this New World which we explore, I shall say later who they were, those who the journey undertook, not seeing it done and ended in a moment. My interpretation: I feel Villagrá says much in his final statement.. “Of this new world,” can mean the world they are entering, meaning New Mexico, or it can mean “the new world of knowledge” he has just entered, in view of what he has just seen: the beings, their flights, the vessel, the lack of anything familiar, the lack of explanations, etc.. Certainly his mind would never be the same!! He says he shall say later “who they were, those who the journey undertook, not seeing it done and ended in a moment…” does this mean he received some knowledge from them as to who they really were? Or does this mean he will share his interpretation of who they were at a later date? Are “those who the journey undertook”, the beings? Or, the people in the caravan slowly traveling north? I think he has learned, perhaps from the beings, that they have traveled far to come to this earth. And he doesn’t understand or can comprehend that thought as he says, “not seeing it done and ended in a moment”. Can this mean that he didn’t see them arrive, so can’t understand how that massive “heap” could have moved through the air and brought them here? And finally, the statement: “ended in a moment”. Can this mean he saw them leave, and as many have reported even today, when the crafts take off, they do so in an instant, almost as if they disappear out of sight! Thus again, his statement: “ended in a moment”. When Villagrá says, “I shall say later who they were”, one might think that at some later date, he wrote more of this encounter, and perhaps then, if that “Canto” or report is found, we will all know more of this strange encounter he wrote of, while on Onate’s Expedition into this land we now call New Mexico. Certainly no dream or made up story of a witch or demon, but the recording of an event that could only be explained in the words and experience of his time. New Mexico is a land which has certainly seen its share of unexplained mysteries, such as at Roswell, Socorro, and in the mountains of northern New Mexico around Dulce, so rich in accounts of sightings of beings and unexplained flying crafts. And so ends this interpretation that I found so fascinating and that poor Villagrá found so mysteriously perplexing! Villagrá gazing skyward as the vessel flies away.

0 Comments

Excerpt from the novel, En el nombre del Padre y del Hijo

by Arnold Carlos Vento Eagle Feather Research Institute [email protected] ISBN 1-893175-04-9 Santos Aguila de la Paz había quedado suspendido viendo tras el Cristo del altar. Estaba solo en la iglesia vacía cuando le asaltó una voz lejana: ¡MUCHACHO!... ¡Ya se acabaron las misas para este día! ¿Qué te pasa? ¿Hay algo que te molesta? ¡Ay Padre¡ ¡Qué susto me dió! ...No, no tengo nada...es que...se me fué el tiempo, pensando...pero...bueno, gracias, Padre... Y se fué escurriendo Santos sin doblar las rodillas ante el altar, dejando al cura atrás rascando su cabeza calva... Follow up: Ese día me reuní con Francisco y Jesusita Candelaria, mis padres adoptivos, y me recibieron con mucho amor y cariño, haciéndome comidas especiales con mi postre favorito de plátano, galletas de vainilla y coco. Lo que resultó fueron las noticias inesperadas, la decisión de mudarse a Salem, un poco más grande que Santa María situado unos 15 kilómetros al norte donde Francisco trabajaba de carcelero en la cárcel del condado de Morelos. Y con ellos me fuí a pasar nuevas experiencias. A Panchito le acababan de ofrecer el puesto de Alcaide con un pequeño aumento de sueldo pero con trabajo para Jesusita encargada de las mujeres viviendo dentro del terreno penitenciario y la enorme cerca con entrada electrónica. Y allí en una casa que se había traído de una base aérea y pegada al edificio de ladrillo principal, fué dónde empecé de nuevo mi vida de este lado. Como eran los últimos días de agosto, la temporada escolar estaba para principiar y decidieron los Candelaria que yo siguiera en la escuela Católica de Salem. Se llamaba Sacred Heart o Sagrado Corazón y las clases eran algo avanzadas. Las clases siempre empezaban con el saludo a la patria y luego a nuestro señor: "My country 'tis of thee sweet land of liberty." "Our Father who art in Heaven, hallowed be thy name." Aparte de un sin número de materias, había catequismo que se tomaba como lo más alto de la verdad y se tomaba de memoria y de esa manera siempre había una respuesta aunque no sabíamos por qué. No es que no había explicaciones, sino que las explicaciones nunca nos daban más luz o comprensión. Y yo, desde el primer año siempre me fascinaban las velitas prendidas pero por alguna razón no me entraba al corazón con certeza lo que estaba pasando en el altar. Y no es que le faltaba respeto a Dios porque yo sentía una conección muy profunda con Dios pero me llegaba siempre de otra manera. Es que yo sentía, que lo que se decía y lo que se actuaba salía muy rutinario y no llegaba verdaderamente al alma. La iglesia era muy grande y muy moderna, hasta tenía aire acondicionado. Hasta no parecía católica porque los santos tenían unas caras y cuerpos largos y los Padres eran gringos y hablaban un español muy mocho en la misa para los mexicanos. Después de un tiempo me metieron de monaguillo sin darme instrucción. No había más que tratar de recordar el papel de otros monaguillos aunque la primera vez que lo hice, el otro muchacho me hizo señales con las cejas y los ojos para sonar las campanillas y para salir a traer el vino y agua. En esta misa, estaba el muy famoso Father Paster, por ser repelón, quien se impacientaba con cualquier cosa. Le di agua para que se lavara las manos y luego tomó la toallita. Cuando se llegó el tiempo de echar agua, más el vino al cáliz, yo, después de echarle un tanto de agua, le seguí echando vino con mucho cuidado y reverencia cuando echó el Padre un gruñido, sambutiendo el cáliz para que le cayera una cascada de vino rápidamente. Con cientos de ojos atestiguando el acontecimiento vergonzoso, no me quedaron muchas ganas de repetir ese rito sagrado.... Lo más divertido era el recreo donde diferentes grupos se dedicaban a distintos juegos. Era aquí donde se hacían las alianzas y sabía uno quién iba a ser tu sombra o camarada. Habían dos hermanos bolillos que por alguna razón no les importaba jugar o asociarse con mexicanos, pues la mayoría del tiempo en el valle siempre había una separación y reservación con escrúpulos para los de habla española, como si tuviéramos costra o la rabia. Estos dos hermanos se llamaban Donnie y Ronnie Fastlender y vivían afuera de Salem en un rancho. Nos contaban con mucho entusiasmo de las aventuras del monte, andar a caballo sin silla, estilo Comanche, la caza de gatos silvestres y lo hacían como si saliera directamente del teatro Rex del lado americano en Santa María donde había episodios de la selva. La invitación se extendió a todos pero creo que yo fuí el único que fué a dar a su paraíso escondido. Tenían dos caballos que creo que eran novios porque tan pronto que uno se movía el otro le seguía. Esto yo no lo sabía y me dieron al más jovencillo que tenía un espinazo largo y el pícaro Ronnie, el mayor, se arrancó como si fuera seguido por el diablo mismo y mi caballo tomó vuelo como un rayo y no tuve más recurso que agarrarme del pelo del crín, saltando como un grillo en un carrera de muerte, dándome golpes en la cola, tanto que, al ajustarme a un lado para amortiguar el golpe con la nalga, salté para arriba cayendo encima del pezqüezo, tijereándolo con las piernas, de manera que resulté al revés con el osico del animal en mi cara. Viendo lo que había pasado, después de mucha risa, Ronnie se paró dando alto al otro caballo: "That's not the way to ride the horse; you got it backwards!" El susto me llegó un poco después, pues no tuve tiempo de pensar en lo que pasaba. No sé cómo no se me quebró el "pezqüezo", ese atardecer. Después supe que estos no eran bolillos de por aquí sino que del Norte donde no se conocen los mexicanos..... También me hice muy amigos de otros dos hermanos que se llamaban Frank y Ray García, quienes eran muy listos para todo y consiguientemente se metían en toda actividad. Una vez, tuve que pedir permiso para salir al escusado, que estaba afuera, apartado del edificio principal, y allí fué donde ví que se estaba quemando el escusado por el humo que salía. Pronto me dí cuenta que Ronnie y Donnie encabezaban un grupo de fumadores. Chupaban unos cigarros que había hecho Ronnie de un tabacco viejo, que por hacerlos con rapidez, salieron desfigurados entre boludos y flacos. Estos muchachos eran los principales para el partido de futbol americano que se jugaba en una cancha dura y llena de piedras y hormigas. El año en la escuela católica se pasó sin novedades y sin saber por qué, Jesusita decidió que ya era suficiente con la escuela Católica y, probablemente por razones prácticas, nos matriculó en el último año de la Junior High School. El hecho de ir a la Junior High estaba como el sí pero no del tío Lucho. Había más estudiantes por clase y más desorden. Me gustaba que no había tanto mandamiento a cada minuto pero aquí la cosa iba de Guatemala a guatepeor. En la clase de matemáticas dada por una señora rete-gordiflona que le llamábamos "Old Lady Wolfe" (no era vieja y sin embargo...), había un tal Liborio alias el Chalán. Creo que así lo bautizaron porque traía siempre unos zapatos tan anchos y grandes que se parecían a los del chalán que cruzaba el río fronterizo en Santa Rita. Era el Chalán un tipo muy pícaro y le gustaba aún más la atención, echando siempre mil puntadas pero dando la impresión que estaba en todos los casos en control completo. Y así fué precisamente con la paliza que recibió de la Old Lady Wolfe. Había estado ya por mucho tiempo haciendo ruido y molestando gente allá por el último asiento trasero hasta que a la "ticher" se le colmó el plato. Moviéndose como un remolino que se lleva todo de encuentro, llegó este camión enorme con tanta facilidad que no supo el Chalán qué le pegó: tomando el libro que traía la maestra gordísima le dió con los dos brazos enormes, mil páginas, mil veces en la cabeza del Chalán y éste nomás risa y risa mientras le caía tanto conocimiento. También tuvo esta suerte (desgraciadamente) otro muchacho que se llamaba Lugones. Estábamos en un pequeño salón de clase para observar el Study Hall donde un señor pelón y medio nervioso estaba de maestro. No sé quien le aventó un proyectil de papel a Lugones, quien, por habilidad atlética, pudo pescarlo con gran destreza al momento de levantar la cabeza el maestro. En tanto, el pelón le dió orden que se saliera de clase y que fuera a la oficina del director de la escuela. Lugones, siendo inocente, se negó diciendo que él no había hecho nada. No gustando que le negaran, el pelón lo tomó del brazo con un movimiento violento y sin acabar su maniobra le apagó las luces Lugones con un riatazo invisible de pandilla callejera a su cara, dejándolo tirado en el suelo. Después de unos minutos pudo el maestro pelón levantarse a gatas corriendo, escurrido a la oficina del director. Ese día, al Chalán le cayó todo muy en gracia y a Lugones nos pareció como Chucho el roto, el Tarzán del barrio escolar. Francamente, no sé qué aprendí en esa escuela pública, pos ni en el recreo había libertad para la raza. En toda la escuela había, entre toda la bolillada de maestros, sólo dos maestros de ascendencia mexicana, pero nomás en las cachas tenían lo mexicano porque nunca se les vió hablar una sola palabra en español. Para nosotros nos parecía que estaban agabachados. Uno de ellos era el coach Espronceda de Physical Education o P.E., como lo llamaban todos. Aunque sus acciones nunca mostraban lo personal, tenía la regla de no permitir hablar en español mientras jugábamos a touch football. Para toda la raza, criada con puro español en la casa, esto era como pedir que no comiéramos comida mexicana casera. No faltaba en el momento máximo gritar: ¡Tira la bola, buey! ¡Pa'cá! ¡Orale! ¡No! ¡Pa'cá, buey! Y a correr, como mulas, alrededor de la cancha cada vez que nos salía una palabra en español. Ese año salí como el más veloz de toda la clase... Al terminar el año escolar salimos todos de vacaciones en el carro viejo de Panchito. Iba Doña Chemita, Jesusita, Panchito, Lucía y yo en un Plymouth viejo del año treinta ocho. Como Panchito era oficial del gobierno americano, conocía a todos de la migración al lado mexicano y fué fácil arreglar una visa para mí como hijo legítimo de los Candelaria. Las carreteras mexicanas eran angostas y boludas y los carros viejos americanos se calentaban con la nada. Ibamos todos muy contentos cuando mucho antes de llegar a Cartagena se le acabó la esperanza al Plymouth viejo. Y allí nos quedamos. Salió Panchito a buscar ayuda dejándonos solos allí toda la santa noche. Las mujeres rezaban el rosario pidiendo protección y los coyotes le daban segunda dentro del vacío de la oscuridad.... En otra ocasión, decidió Panchito salir por Carmona en lugar de Reynero, porque por allí no conocíamos y para él, el conocer nuevos lugares era educacional. Todo iba bien hasta que empezó a llover cascadas y el río Lobo se creció dejando el vado sumergido entre la corriente tumultuosa y agitada. Panchito preguntó: Oiga, perdone, pero ¿cuánto dura el río crecido? Pos,...eso depende. Durará unos cuantos días? Pos, es posible. ¿No habrá un camión por aquí que nos estire hasta el otro lado? Pos, quien sabe. Las mujeres hicieron campo y cocinaron un cabrito que había comprado Panchito, al estilo casero en su sangre y luego después en salsa de tomate con especias. Para nosotros era una aventura todo esto, aunque los remolinos de la corriente nos daban mucho miedo. Después de tres días se bajó la creciente y pudo Panchito conseguir un troque que nos estirara, pos todavía había como un metro de agua encima del vado. El agua llegó casi hasta las ventanas pero los rezos de Doña Chemita y Jesusita nos hicieron brecha hasta el otro lado. Como había llovido mucho, la subida en el otro lado se había hecho un zoquetal de los diablos y el pobre Plymouth ni con mariguana hubiera subido. Dijo Panchito: No se apuren. En México, ¡todo se hace! Se fué y regresó con un campesino con sus dos enormes bueyes, uno colorado y el otro canela y con una buena amarrada, la sumida de la pata de Panchito y nosotros empujando mientras las llantas nos rociaban de zoquete, pudo el viejo Plymouth treinta y ocho escalar la cima de ese imponente barranco. Ese día surgió Panchito el hombre cabal y héroe nuestro, digno de ser el oficial respetado y honesto que era en el condado de Morelos.... Arnoldo Carlos Vento, a teacher, writer and critic, was born in the Rio Grande Valley and was raised in the small community of San Juan, Texas. With more than ten books and forty articles to his credit, Dr. Vento is currently an Emeritus Professor at the University of Texas-Austin and Executive Officer of Eagle Feather Research Instute. He developed the first Chicano Studies Program in Michigan in 1972 and was a co-founder of Canto al Pueblo, a national forum for artists and writers, in 1977. His father was the Head Jailer in the Hidalgo County Jail while his mother was an activist writer and participant in the Mexican American Civil Rights movement beginning in the mid twenties and continuing through the seventies. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed