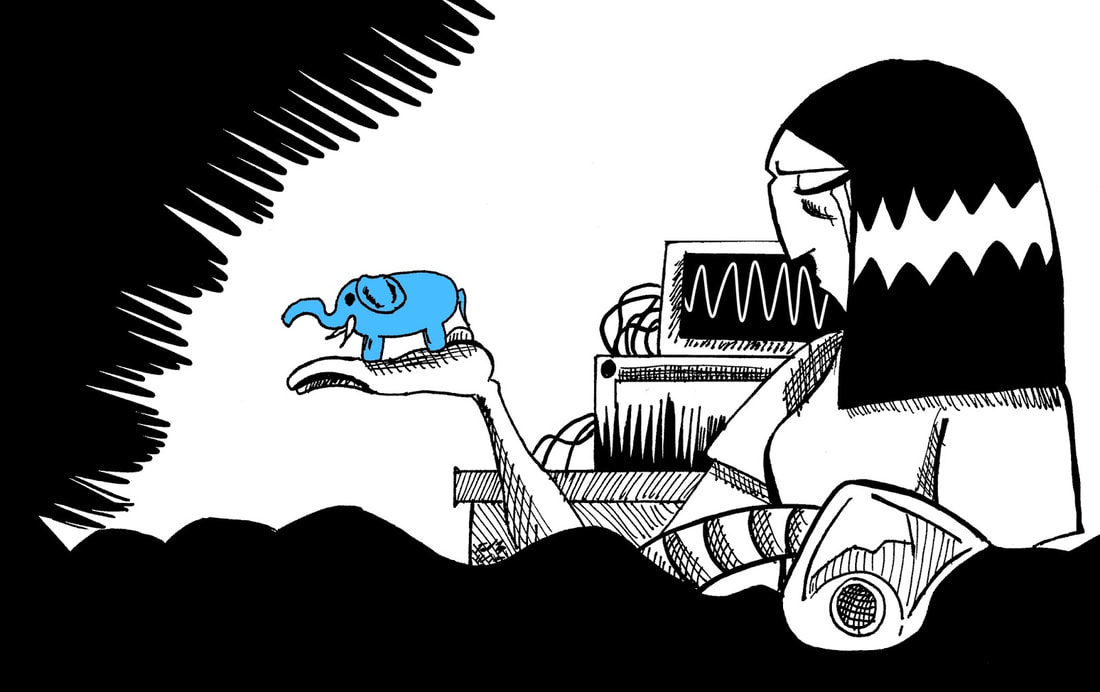

Death and Elephants Elena held the blue porcelain elephant in her right hand. With her fingers, she rotated it in circles against her palm, squeezing it every so often, to feel the unique shape its edges made. Elena lifted her eyes from the elephant in her hands to her mother, who lay still beneath the covers of the hospital bed, morphine pumping into her veins. She thought how absurd it was that her mother—who had never seen an elephant outside of a zoo—collected elephant figurines wherever she went. Under death’s impending weight, the amassment of stuff seemed ridiculous to Elena. Life itself, its thin, brittle brevity, seemed ridiculous, too. Sitting in the hospital room, Elena thought much about her own life as she watched her mother’s life dwindle to its end. She thought about the miles upon miles she had traveled in her 34 years of life; the magnificent sites of the world she had seen and never bothered to memorialize through photographs or journals; the love affairs she had felt and lost; the face that age had morphed in the mirror; every momentous and minute memory that made her who she was. All of it seemed random and aimless to Elena now, circumstances haphazardly pushing and pulling her along the tightrope of life, of her life that she could only fully know herself. Her memories would die with her, imparted to no one. She then understood that her mother possessed a life, too, intimate only to herself that Elena would never know, and its only remnant would be a collection of glass and porcelain elephants. Elena’s heart began to quicken with panic. Her mother would be gone. The permanency of death felt real and unbearably near. Some small part of her, from long ago, believed that her mother could never leave. The enveloping presence of a mother felt forever. She thought of the nine months she didn’t remember inside her mother’s womb when she was, literally, part of her body, absorbing nourishment and space. Once plump and pregnant, her mother’s body was now frail and wilted, its blood cooling and slowing in the veins. Elena remembered plunging her face into her mother’s breast as a child, seeking comfort in her warmth cloaked with a plush turquoise sweatshirt, smelling of fresh detergent. Even as an adult, her mother’s body represented a cradle of respite; Elena’s mascara-mixed tears stained many shoulders of her mother’s fine sweaters. The body would turn to ash, but Elena found solace in the blood they shared flowing within her. What does a daughter do without a mother? Elena knew that when her mother passed, a part of herself would die, too, but she knew she would also gain all of herself because she would be able to sever the artery that bound them together in life. Elena was an ambitious woman. She held two master’s degrees and quickly climbed to top executive management at her company. She understood life as a competition, divided into winners and losers, shepherds and sheep. From the first science fair blue ribbon won at age ten, Elena decided that she was a shepherd and a winner. She had little patience for most people and their complexities. She found them wet and messy like paper-mâché, made up of emotional baggages and idiosyncrasies. But Elena was a beautiful woman. Cursed with her mother’s thick black hair and alluring dark eyes, a continuum of men pleaded for her affection over the course of her life. If she was honest with herself, she couldn’t find a man’s love worthy of commitment because a man’s love is like a knife that cuts you swiftly and deeply in the beginning, but fades and dulls over time. Her mother’s love, however, was constant and continuous, omnipresent like her own heartbeat. As such, Elena found comfort in her isolation from others. Despite this semblance of independence, Elena often felt like her mother’s eternal child. She never disobeyed, sitting still, like a doll, for hours in her frilly dresses and neat braids when told to do so as a child. She spoke to her mother daily, frightened to explore the uncertainty of life without her mother’s counsel. Should I wear this dress or that skirt? How do I fry an egg? Do you know what this rash is on my arm? Should I ask for the promotion or should I wait? Is he right for me? She was an overgrown, clumsy little girl in women’s clothing who phoned her mother after any minor stress, seeking comfort in her caretaker for reassurance. Maternal authority demanded that life would be all right. Her mother’s death would kill this coddled child who had always belonged to someone, leaving Elena as a fragmented adult who belonged to no one. But the elephants would belong to her. This blue one, here, she had singled out from the dozens on display in her mother’s curio cabinet. She had impulsively grabbed it and slipped it in her coat pocket on her way to the hospital. She thought it pretty, the way it looked like a China plate rolled up into the shape of an elephant, the way the blue faded into white down the trunk, and the thin, delicate navy lines that intertwined along the spine. She would always wonder about the stories behind each of her mother’s elephants, but she knew this one had been a gift from her father. He brought it home from one of his trips overseas. Elena remembered being a young girl and watching her mother carefully open a white box to reveal the dainty blue figurine. Her parents embraced and kissed each other affectionately before her father placed it in the cabinet where it would remain all those years. Elena and her father had got along well, never particularly close, but now he seemed a stranger. Now all fathers became strange to Elena: male ingredients that facilitated the bond between mother and daughter. He was a good man, a good husband and father, dutiful and present. He provided for their family of five, working eight hours in an office downtown and taking occasional international trips to earn a comfortable salary that afforded more than enough food, shelter, clothing, advanced education, and so on for Elena and her two sisters. Elena found him a pleasant man, never irritable and always in good humor. Her mother loved him passionately, revealing juicy morsels of their early years together to Elena: his poetic love letters and professions, the way his deep blue eyes stared into her soul, his persistence in courting her at nineteen, and most shockingly, his appetite as a lover. This person her mother described was foreign to Elena. With the exception of his thick eyebrows and high cheekbones in her own face, she couldn’t discern him from any other male acquaintance. She didn’t know him, not like she knew her mother who never worked, constantly vulnerable to the emotional disposal of her daughters. Elena’s father didn’t know her and he would never understand the intimate knowledge a mother imparts to her daughter on the experiences of being female and how to navigate its complicated limitations—its mess of empowerment and skincare routines, ironing the kinks in your hair and choosing the right man, self respect and pap smears, careers and hormones that made you want to burst, high heels and higher education—it was all very confusing. No, he couldn’t understand. In the end, Elena would be left alone with her father—they both would be left alone—with their respective gaping wounds of loss, bathing in the uncomfortable quiet between them. But at least she would have this elephant. Still holding the object, Elena rested her head on the bed beside her mother. Everyone would soon arrive to crowd the hospital room with more flowers and cards, a strange ritual for an impending death. She then placed the elephant on the bed, facing her, so she could explore its tiny painted features. It conjured images of her mother’s gleeful smile when she received it, the purple terry-cloth robe and dingy white slippers she wore that morning, her thick glasses and disheveled black ringlets of hair; the minivan she drove when she picked her and her sisters up from school; her melodious laugh; her long, dainty fingers; her stubbornness; her warm embraces; her calming voice over the telephone during college; how she prepared three tupperwares containing the exact same number of pear slices for preschool to ensure equality among sisters. Elena imagined her mother at nineteen with her black curls, disco-era dresses, and gap-tooth smile, exuding sex, depth and levity—a rare, beautiful combination that allured her father; their honeymoon in Paris; their wedding in Mexico; and her mother’s beginnings as the only curly-haired Cuban girl in Massachusetts. Soon everything would be gone, her mother’s life and body crumbled into nothing. But somehow her mother would remain real in the elephant. All the other elephants were mysteries but this one--this one—she knew. With the elephant, Elena could know her mother if she didn’t know anything else at all. Elena then began to cry. Suddenly, she heard a knock at the door. She quickly wiped the tears from her face, took a deep breath, and placed the elephant into her coat pocket. She opened the door and greeted her father. Elena welcomed him into the room and they both returned to the hospital bed, sitting on either side. They struggled to make conversation. Elena clutched the elephant in her pocket as they sat in silence, and waited.  Cristina M. Luna, who lives in Philadelphia, says her writing is often influenced by her upbringing as a Latina in the Washington, D.C. area and her work in Latino and Spanish-speaking communities. A graduate in English from the University of Delaware and with a Master’s in American Studies from George Washington University, she was also a fellow at the Smithsonian's Program in Latino History in Culture at the National Museum of American History.

0 Comments

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed