X |

| Shaiti Castillo is a Mexican-American writer from Mesa, Arizona. She is currently residing in Tucson, Arizona where she recently graduated from the University of Arizona with a Bachelors in Creative Writing. As a first generation student, she is proud to be the first in her family to graduate from an accredited University. She spent the majority of her childhood visiting relatives in different parts of México and takes great pride in her heritage. She hopes to share her cultural experiences through the art of storytelling. This is her first publication. |

Edén

by C.L. Martín

The dirt rises in mounds between her palms, and I don’t need to watch to know what she is making. She continues as I yank at weeds, the small stingers of the melon vines sinking into my fingers as they accidentally collide with one another in my haste. Mamá pinches the soil between her fingers, attaching a smaller mound and four appendages to each of the twin mounds. She pats their surfaces, smooths them.

“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth,” she begins, and my mouth forms around the next verses while I work. We recite it together, our voices barely above a hush.

“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them,” she says, then rests her knees in the dirt. She doesn’t need to finish the story; we both know how it finishes. And we both know how she will finish it.

“God gave us a second chance,” she concludes, looking down at her creations. “He gave us a second chance.”

She smiles out at the line where the bare dirt succumbs to a wall of green, of fronds and vines and leaves alive with the hum of insects, of birds calling to one another through the gloom.

“And why you and Papá called me Edén,” I add for her.

“That’s right,” she chuckles, nodding. “That’s right.”

I have been expecting this ritual since just before dawn, when Mamá’s groans woke Pablo and me and stirred the younger children, and Papá had to shake her awake, rocking her in his arms.

“You’re safe, woman, you’re safe,” he whispers, and I can hear her sharp breaths ease into sobs. “We made it.”

“We made it,” she repeats.

“We crossed the wilderness,” he says.

“We crossed the wilderness,” she says.

“We crossed the sea,” he says.

“We crossed the sea,” she says.

“And we arrived in the promised land. We are in the promised land.”

Her voice is calm again. “We are in the promised land.”

Pablo and I see the whites of Papá’s eyes through the twilight as he returns our stares, and without a word we push the blankets off us, dress ourselves, and go outside to ready the firepit. He lights the lamps and the fire, and I fumble in the darkness to hang the pot over the burgeoning flames. Pablo’s eyes roll toward mine, and mine to his. And I think of Mamá’s cracked hands and dirtied nails, fashioning the soil after her own image.

These fits come like freak storms, but I learned early that they almost always come when I ask questions, when I invite the past to come creeping in from its hiding place just beyond the tree line. Suddenly, my vision fills with white light and I am small again, not much older than the twins, the top of my head just barely reaching Mamá’s hip. She has given up on coaxing me to help her shell the peas and instead smiles, allowing me to embrace and kiss her swollen womb. Juana. Pablo plays with something on the floor, barely able to walk.

“Mamá, do you got a mamá?”

“I told you: In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth…”

“But that was Adán and Eva. And they had to leave the Garden. And they had Caín and Abel, but Caín killed Abel, and then he and his family wandered the earth.”

She says nothing, her smile unwinding at the edges.

“How’d we get back?”

“Why you ask so many questions?” She’s trying to be playful, but there is a command behind her question.

“Are we the only ones here?”

“Go play with the doll Papá made for you,” she says as she gestures to the wooden doll on the floor with her knife.

That was the first time I remember her screaming in the night, Papá cradling her, chin atop her head.

The next morning, Mamá perches me in a chair beside her at the table and makes me watch while she makes bread with the flour she bought from the trader. She pulls at the dough, rolls and unrolls and rolls it again into a perfect orb. Finally, tearing off a handful, and then another, she makes two human forms on the table in front of us.

“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth,” she begins.

I don’t understand, and wait for her to continue.

“Say it with me. ‘In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth…’”

“‘In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth…’”

We recite it all the way to when God sent Adán and Eva from the Garden, and cursed Eva with the pains of childbirth, my eyes roving over Mamá’s distended belly.

“We got back. And that’s all that matters. You understand?”

“Yes, Mamá.”

“Everything that happened before—it doesn’t matter.”

“Yes, Mamá.”

But still I find ways to ask my questions in the years that follow, sprinkle them in among the scratch while I help her feed the chickens, drop them into the holes she makes in the soil with her fingers when we plant for the new season.

“Mamá, why you and Papá got brown eyes, but I got green ones?”

“Mamá, why is Papá’s skin darker than ours?”

“Mamá, where does the trader get all our flour and seeds and…”

Mamá grunts and holds her back. She leans back onto her haunches. At this point Juana is about five, and her successor, Diego, four, and Mamá has begun to show again, her belly like a squash growing on the vine. I count out on my fingers like Mamá taught me: There are one-two-three-four of us, and this one will make five. Mamá blows air through her lips, but then leans forward again and returns to gardening.

“Is the baby coming?”

“No, it’s too soon. My back must just be cramping.”

But she wakes early in the night, in the grips of one of her bad dreams, and Papá carries out their ritual. But this time, it is not enough; her breaths continue fast and sharp in the back of her throat. Papá rises and dresses, then plops me into the bed next to her.

“I gotta go get help for your mother,” he informs me, “take care of her while I’m gone.”

Mamá pulls me into her, takes my hand into hers, but it is hot, sweaty. Pablo watches from our bed, his eyes shiny in the candlelight, and she opens her other arm in invitation to him too. We sit on either side of her, but soon she breaks free from us, screaming. Papá returns with the woman who delivered us. She strokes my cheek in recognition before handing me to my father, who returns Pablo and me to our own bed. But we do not sleep, cannot sleep over Mamá’s agony. By sunup, Papá orders us to feed the animals, and we do it in a rush so that we can return to our vigil. But he tells us to stay outside, shuffles Juana and Diego out with us. We sit on a cluster of stumps not far away, swinging and hitting their bark with our heels, stomachs empty and livid. Finally, the commotion in the shack subsides, and the silence is filled with the sound of insects. No one opens the door for a long time.

When Papá lets us back in, Mamá is sleeping while the woman still tends to her. Papá summons us around the table. A wadded rag is the only thing on top of it, wetted with what looks like dried water and blood. He removes a corner so that we can see the face, its unformed features.

“This was your sister,” he tells us. “We’re gonna give her a name before we put her to rest.”

“What about Mamá?” I ask. “She gonna make it?”

Papá looks at the woman, who glances back at him and nods. He relays her nod to us.

We named her Petra. Papá digs the hole extra deep so the animals cannot get to her and carefully places her inside. We place stones over the scar in the earth as we pray. I feel a hot tear wind down my cheek.

Mamá’s womb remained empty for years after that, but when it was ready to accept life again it was blessed twofold. Aurelia and Pía. It is slaughter season, and Pablo and I shadow Papá as he kills, drains, and cleans the pigs. Juana and Diego, still too young to help, play in the clearing. Papá disappears around the back of the shack to find something.

“Edén,” Diego calls out to me.

“What?” I reply.

“Why does Papá walk like that?”

“Walk like what?” I know what he means, but hope he will catch my disinterest.

“Like he’s hurt.”

Pablo’s eyes roll toward the shack, where Mamá is working, seemingly every part of her swollen with the new lives she is about to bring forth, then meet mine. I stomp toward the two of them and cover his mouth with my hand.

“Don’t ask questions like that.”

“Let me go!”

“You’ll upset Mamá.”

“Stop!”

He bites my hand, and I send him backward into the dust. He cries, holding his bottom, and tears off toward the shack.

****

I think Mamá’s latest nightmare has something to do with the visit from the trader the day before.

He and Papá are standing outside the shack, arms folded across their chests and their voices low, as I bring in the water. Both regard me for a moment and stop talking as I make my way toward the front steps; for a moment, I note their curious differences. They share the same dark hair and dark skin, and yet Papá’s features are softer, his hair a net of curls while the trader’s sticks out in straight, jagged tufts from under his hat. I noticed the same differences between Mamá and the woman who delivered us, who is the trader’s sister or cousin or some other relation, her sheets of hair always wrapped round and round into a knot at the back of her head. I hasten up the steps.

The murmurs begin again as the door closes behind me. Mamá has propped open the flap of wood that serves as our only window, and stray words leak in. “War.” “English.” “San Agustín.” “Cuba.” I recognize only the first, think about Jericho and Josué and his trumpets. A sound disrupts my sprawling thoughts. It is a sigh, almost a whimper, and I turn to find its source. Mamá has been sitting at the table, taking a break from her work, and she stares at the wall—in her trance—as if she is looking through it, to the trees just beyond it.

Tonight, I think I have seen a spirit. It was only for a moment, before it turned away and slipped between the trees, but it was a man, his skin pale and translucent. But he looks like no man I have ever seen, that is, he looks nothing like Papá or the trader or the other men Papá says are the trader’s kin, who I see hunting from time to time in the forest. Papá and Mamá have taught me that spirits are as much a part of the landscape as the creatures who dwell in the forest and in the swamp that rings our patch of land, though this is my first time seeing one. They are from the time before we returned to Edén, they explain, people who never accepted God or who were condemned to purgatory for their sins. My heart thumping, I scurry up toward the path to the shack before the sun goes down for good.

The fire is still going, though dinner was more than an hour ago. Mamá sits off to the side, the flames illuminating her face. Papá is silhouetted, his back to Mamá and the fire, and he glowers out on the trees. He does not look at me as I approach.

“Go find your siblings and get them ready for bed,” he commands.

“I saw a spirit,” I mention, my excitement somewhat diminished by the shortness in his tone. His eyes drop to the ground, but he says nothing, does not move. He and Mamá remain outside some time; their whispers awaken me as they grope through the darkness toward their own bed, some hours after the girls and I fell asleep in a tangle on our mattress, Pablo and Diego on theirs. I smell the smoke on their clothes as they pass.

I lay awake afterward, too hot and my mind too restless. Papá has left the flap open to allow in the fresh air, but it is just as stifling and heavy as that inside the shack. It is furious with the sounds of frogs and insects. Twigs snap as something moves through the trees at the edge of the clearing. Perhaps it is a deer or some sort of scavenger, or maybe even a puma attracted to the smell of the animals tucked safely away in their huts. The ruckus continues, and I roll to my side, trying to bury one ear into the pillow, press my fingers over the other. I hear Mamá or Papá turn over in their own bed as well.

My body lurches upward, and I realize I had drifted off, for how long I do not know. Papá and Pablo are sitting up too, and Mamá grasps onto Papá’s elbow, asking him what is wrong.

“I heard a voice,” I whisper to them.

“Me too,” Pablo says back.

“Stay where you are,” Papá orders as he tosses off the thin blanket covering him. Mamá remains paralyzed in her spot on the bed.

Papá prepares a lamp and edges toward the flap. He lets the orange ring of light spill onto the ground just outside the shack, moves it from left to right, opens the flap as far as it will go to gaze further into the darkness. Suddenly, he startles and drops the lamp, breaking it. The flap slaps shut.

“What is it?” Mamá hisses. “What did you see?”

“Boy, grab a knife,” he barks at Pablo, who complies. He selects one of the machetes hanging near the door, next to where Papá keeps the knives he uses to kill the pigs.

“What is it?” Mamá repeats.

“It’s them,” Papá utters, and there is panic in his voice. “They found us.”

My mouth is agape, wondering who he means, but Mamá must know for she hurries to the knives and selects her own. The younger children are awake now and squeak like baby birds over having been woken, asking their own questions about what is happening, but Mamá shushes them and herds them into her and Papá’s bed. I at last rise to my feet and grab my own knife, one of the ones I’ve seen Papá use to cut through bone, and shuffle back toward the other children, feeling stupid and helpless as I hover next to the bed, not quite sure how to wield my new weapon.

We hear it again, a voice, but this time there is another, and another, and still yet another—a whole chorus. Suddenly, all four walls of the shack begin to clatter with the sounds of fists and rocks and sticks against the boards. It stops just as abruptly. Laughter. I can hear them talking to one another, but I cannot understand them.

A high-pitched whoop pierces the thick air. One of them calls out in a strange chant, one that sounds like when Papá summons the pigs to their slop. The banging and cackling begin again, until I think the shack will come down. Mamá is praying under her breath, the knife clutched between her palms. Papá and Pablo have barricaded the door with the table and chairs, and hold them in place as the boards rattle around us. Papá glances back at Mamá, who opens her eyes and stares back at him. It is like they are communicating.

“Come on, now,” Mamá says, and she starts pulling boards from their place in the floor, as if by some god-like strength. Papá nods at Pablo and he joins her. Finally, when they have removed about half a dozen boards or so, she gathers all of us around her.

“Pablo, Edén—take your brother and sisters and follow the swamp south. Just stick to the water, and you’ll find Cesar’s village,” she tells us, referring to the trader.

She pushes Pablo through the hole and under the house first, then me. Papá has built the shack up so high on its stilts in case of a flood that I can almost stand my full height under there. Mamá begins to toss the smaller children to us, who lay down in the dirt on their stomachs and wait for directions. I can feel spider webs on my skin and I am certain that their occupants have crawled into my hair and clothes. My skin begins to itch. All six of us in the hole now, we look through the panels; torchlight seeps from the front of the shack, and all of the commotion now seems gathered around the door. I crawl over and peer between the panels: there are one-two-three-four-five-six figures hovering just behind the torches. Their skin is illuminated, pale—spirits. I gasp.

Pablo carefully removes a panel on the furthest most corner from the noise and ushers us through it, and we run into the darkness. We stumble through the forest toward the swamp, tripping on roots and fallen branches and bushes, until we can hear the voices no more.

We drift so far into the forest that not even the slightest of light can pierce through the canopy, and we must wait until dawn before we can continue. The younger children sleep in the branches of a drooping old oak. Eventually, we follow the blue haze of twilight toward the water. My head floats with hunger. The sun has reached its highest point when we find a gathering of shelters near the marsh, and filled with a newfound panic, we shout and run toward them. Their inhabitants meet us as we approach, bewildered. We collapse at their feet, panting and sobbing and still shouting.

“Cesar,” I say again and again, hoping that we have found the right place.

It is some time before I see him rushing toward us, some of the other villagers having gone to fetch him. Some of the women have managed to calm us and now sit with the twins in their laps, holding food for them as they eat. The rest of us sit in the dirt, still shaking, partaking in our own meals. We tell him what happened, and he wipes a hand over his face.

Cesar invites us into his family’s home, and it is days before I am able to rise. Later, Cesar’s wife will tell me that I slept for some three days. Diego and the twins soon develop fevers, and they remain that way nearly a month, as the first illness begets another.

Some of the men, led by Cesar, go to look for Papá and Mamá. But the shack has been burned, the animals run off, our parents vanished.

A couple weeks after we fled, Cesar summons Pablo and me to his boat, but offers no explanation as he pushes off from the shore. Some half-hour into our journey, more shacks rise from the marshes, and surprise and dismay and even a sense of betrayal wash over me. The inhabitants look like us, and a few wave to Cesar as we pass. We disembark and he takes us to a home near the center of the settlement, where a man stands outside waiting for us, arms crossed. Cesar introduces him as Señor Padilla.

“Come on,” Padilla says, “We got a lot to talk about.”

Padilla invites us to sit on a couple of logs he has converted into seats around his family’s firepit, then takes his own. His wife pushes a couple of clay bowls into our hands, fills it with some sort of rice dish.

“I knew your father,” he tells us. “We served together, over in San Agustín.” He reviews the blank expressions on our faces. “But I gather he never told you about any of that.

“He still came here, once in a while. I told him he should move here with the rest of us, that it would be safer, that we could protect one another, but he refused. He and your mother thought they knew a better way to protect you.”

“From what?” Pablo asks.

“The truth,” Padilla snorts, “the past. Their past. I thought they were crazy.” For a moment, I remember Mamá and her dolls made from dough.

His eyes pass from my face to Pablo’s. They are sharp, impatient, yet read of pity.

“Look, I don’t know what all your parents told you, but we—all of us,” he gestures to the other shacks, “We were born into bondage. Up in South Carolina. That’s a colony up north, belongs to the King of England.”

I think about Hagar and Moses and the exodus and the destruction of Jerusalem and the re-enslavement of the Israelites…

“But the King of Spain, he said that if we ran away here to Florida, we’d be free, so long as we became Catholic and served in his military. That’s how I met your father—doing my military service, over in San Agustín. It was our job to defend the city against the English. He got hurt, during one skirmish. I’m sure you saw how he walked. But we did our job, and then we were free. And most of us, we came and settled out here, but your parents, they went out even further. They didn’t want anything to remind them of what they left, didn’t want you to know about a time we were anything but free. Not til you were older, anyway.”

He trails off, taken over by his thoughts. We continue to eat. Finally, he takes a deep breath, as though he’s been holding it this whole time, and shifts in his seat.

“The English. That’s probably who attacked you all. They made an agreement with the king: they get San Agustín, he gets Cuba. I’ve seen a few of them the last couple of weeks, sneaking around the marshes. Probably fixing to take us back up to South Carolina or Georgia. We don’t intend to stay to find out. We’re going down to Cuba. All of us. I think you all should come with us.”

Pablo finishes his meal and sets the bowl down beside him, and leaning forward, he looks into Padilla’s eyes as if it hurts him, as if he is starting into the sun. “Our people—we got any people here?”

Padilla pauses. “Not that I know of. Your father, he made the journey by himself. I don’t know much about your mother, except that she came here from South Carolina, too. They met at church, there in San Agustín.” He stretches his legs out in front of him, inspects his boots. “But we’d look after you. Make sure you all have what you need.”

I am hollow as Cesar takes us back to his village. I mull Padilla’s revelations. Renacido—that is our family name, we learned, one Papá gave himself after he crossed into Florida. And I think about Padilla’s proposal, about Cuba. Maybe Mamá and Papá escaped and are already headed there.

Or maybe they are out wandering in the forest, like Adán and Eva, exiled from their beloved garden. Maybe they have been taken back to South Carolina, like Padilla said would happen to us. Or maybe they are dead. And maybe the way to honor them is to return to their land, land they owned, and rebuild the shack and pens and gardens, or if not there, then in the jungle that surrounded it, feral. Or maybe it really is to go to Cuba, to tend our parents’ legacy like an ember until its flames are full. To not merely survive. I close my eyes, and I see Mamá’s hands forming figures in the soil. “God gave us a second chance.”

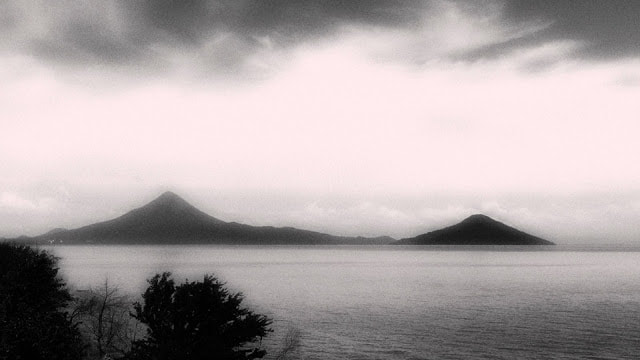

Una Cuadra Al Lago Del Silencio

| I am very good at leaving. Leaving this place, that place, no place; myself. I leave things behind. There. Here. Nowhere. I only come back to you, Silencio. |

I sat on top of a rock near the gated entrance, sipping the remnants of orange juice in my yellow plastic thermos. My mother squeezed fresh oranges every morning, because my family could not afford a live-in Chacha like the other kids. The liquid was still refreshingly cold on that sweltering midday. By the time I finished, everyone but the faded hero cartoon sticker on top of my lunchbox and I, was gone.

Cars zoomed by and I longed to hear the engine roar inside the rattling red hood of my stepdad’s Lada. But it never arrived. In the adventurous spirit of characters like Red Riding Hood from the folktales teachers read before naptime at school, I decided to walk in the direction of Abue’s house all the way across town. Teachers always raved about the heroism of Caperucita Roja when she defeated the Big Bad Wolf with her wit; she was an intrepid pata de perro who didn’t sit nor stay.

By car, Abue’s house was probably thirty minutes away from school. By bus, if one could find an empty seat among the mercaderas with heavy straw baskets heading to El Huembes (the local city market), it was a comfortable hour and a half. But measured in the steps of a five-year-old girl? Abue’s house was a sweat-drenching eternity in the scorching midday heat. As I walked down the unpaved side of the highway, the draft from the speeding cars occasionally lifted my pleated blue skirt, and nearly ripped the insignia from the left pocket of my buttoned-down white shirt. Dressed in blue-white, I probably looked like a miniature Nicaraguan flag in a windstorm.

At a busy light intersection, I sat down under the shade of a mango tree. The skinny branches with long leaves ran for miles into the sky. Suddenly a blue-black Toyota pickup truck screeched to a halt before me. As the cloud of dust settled, I could discern it was La Guardia in disguise: The Big Bad Wolf from the cautionary tales Tío Miguel told me.

When he was a child, La Guardia raided people’s homes like in the Three Little Pigs, huffing and puffing bullets into concrete walls to check which houses crumbled. They didn’t look for chimneys to climb because Managuan homes at the time, no matter the material, didn’t even have doors. Abue would force Tío Miguel to wear a dress before hiding him under the bed so La Guardia wouldn’t take him to a place called Guerra. It seemed no one in my family wanted to go to that place, and I was no different.

Driving around the city disguised as a new wolf breed, La Guardia had a new namesake: La Contra. A Morena with curly black hair tied in a bun, dressed in an olive-green uniform and military boots, stepped out of the front passenger side. Sunglasses, the man at the wheel, wore a similar uniform except for a camouflage cap shading his face. For a slight second, Morena resembled my aunt Ligia who also had a flawless blend of Miskito cinnamon skin. She had the kind of skin shade that chelas like me wanted to have, even after enduring chancletasos from our mothers for standing in the sun too long.

“Mirá vos,” she called for Sunglasses. “¿Dónde vas, chavalita?” she turned to me. I didn’t answer.

“¿A dónde vas, Amor?” she reached out for my hand. When I touched her frosty skin from riding in the air-conditioned cabin, my whole body went numb. I had never been in the presence of a cadaver, but I imagined she felt like one. Del susto, sentí un soplo en el corazón.

“Donde mi Abue,” I murmured.

“¿Y dónde queda eso?”

“Por El Huembes,” I replied.

There was no turning back. She knew where I was going. My trembling legs synchronized to the offbeat patterns of my emergent heart murmur. Surprisingly, I felt like a grownup in that moment, referring to landmarks like a real city slicker. No one in Managua actually uses a number address; our postal codes are defined by the most accurate subjective orientation to places and things. We navigate the city by referring to markets, old buildings, monuments, lakes, or trees: “del Arbolito, una cuadra al lago,” we say. Abue had the habit of asking if a place existed before or after the earthquake, just in case.

Morena opened the door and boosted me up to the backseat, placing my faded lunchbox next to me. As I scooted to the center, my overheated legs squealed as they rubbed against the plastic seats. The door closed behind me and Morena got back inside the passenger side; one last gust of hot air filled the truck, and I knew I had found Silencio. The air difference inside the cabin was palpable; the dead-cold breeze from the vents sent chills to the back of my neck. My mind went blank.

I once heard that all girls should cross their legs when they enter Silencio, specially when La Contra is in the front seat. But that cold breeze would occasionally lift my skirt and feel satisfying as it dried my sweaty thighs. Every now and then Sunglasses would turn his head toward the front mirror. I could tell he wanted to be like the cold air penetrating my pores. Morena gave him some side-eye, but never said a thing. I kept pointing in the direction of Abue’s house, but Sunglasses drove slower. Slower, until time stopped.

I wish I could recall more details about Silencio. But every time my memory roams in that direction, all I can remember is the smell. From a certain smell, una cuadra al lago de la memoria; that is the postal code of Silencio. Sometimes when I return, there is an overwhelming scent of burning plastic, mixed with the coolant from the air vents at full blast. Sometimes there is a pervasive smell of sweat and male cologne infused in the upholstery. At times the smell is a combination of gasoline fumes and burning tires. What I do know is that there is always a smell in Silencio.

The next thing I knew, we turned left at the red-black prism memorial for the militant-poet Leonel Rugama, who never came back from Guerra. As we headed down the street, I could see the outside of my Abue’s house in the distance. The pickup truck pulled up to the front. Abue, in her embroidered green bata, dropped her transistor radio and jolted from her mesedora on the porch. Morena got out first and opened the door for me. I jumped out and ran as fast as I could out of Silencio. Abue’s eyes widened when she scooped me into her arms. Instinctively, she lifted my skirt to check between my thighs. Heart racing, eyes sealed, I squeezed tightly; my legs were shamefully frozen-dry but I was unharmed.

Morena chuckled at how firmly I latched on to my Abue’s body. She gave Abue a warm nod and handed her my lunchbox. She returned to the front seat and rolled down her window. I watched her pull out a concealed red scarf under the neckline of her olive-green uniform, an identifying marker of bold volunteers who went to Guerra. She was not La Contra at all; she was a Cachorra. A Caperucita Rojawho prevented Sunglasses from turning into the cold air between my thighs with her silent wit. I never saw either of them again ever though they knew how to get to Abue’s. I figured like many others, they got lost coming back from Guerra.

Thirty years later, during my weekly talk-therapy sessions, I try to deconstruct why I return to Silencio. Why I sit on rocks for hours. Why orange juice tastes better when served in a thermos. Why I sit under trees to purposely obstruct my view of the sky. Why I gravitate toward any body of water to find my place in the world. Why my nickname is pata de perro. And why I nod in silent gratitude at women who wear red scarves.

La Procesión de Sangre de Cristo

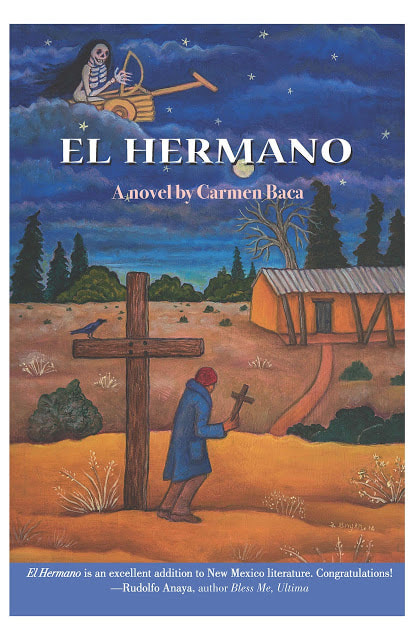

Excerpt from El Hermano, a novel by Carmen Baca

With a review by Scott Duncan-Fernandez

That my abuela was here was no accident, no inexplicable coincidence to agitate my imaginings. For she knew that I had become a novicio the night before, and as médica, she had come to see how I fared. She moved to my side with a jar of her remedio, turned me to my side to rub the romerillo, or silver sage, on my back, and then tucked the quilts around me once again without a word.

My mother placed a mug of warm broth in my hands, brushing a gentle hand over my cheek and pulling a chair by my bed for my gramma before she left for the church with my aunt. A few of the women would give the capilla a light cleaning before covering the saints with cloaks of black this morning to symbolize the dark day of Christ’s death. They would remain concealed until Easter morning, the day of His resurrection.

Settling herself comfortably, gramma took from her apron pocket a small kerchief with a trailing thread and proceeded to continue her embroidery on its edge, the needle whipping in and out of the intricate design with a delicate, almost birdlike fluttering of her hands. I sipped the warm soup watching her, waiting for her to speak. I knew I had inherited my physical appearance from her, the small, thin stature, the nose, and her humor. Had I also inherited a mental power I didn’t understand, or want, from my beloved grandmother?

Before I could ponder the question further, before I could think of a way to phrase my question without hurting the feelings of the tiny woman seated beside me, she spoke.

“You have a gift.”

Her words revived my concerns that the warm broth had begun to dispel.

She looked up from her embroidery. Although this was one time I wished I could turn away, I forced myself to look into her eyes. Bright with tears, hers held a mixture of sadness and regret. When she blinked the drops away and smiled softly at me, there was also pleasure and expectation in their depths.

“The gift of sight,” she began, “is strong in our family though inherited by some, not all, through the generations. And,” she added, “while some seemed only to possess a strong sense of intuition, there were others who had the power to know other’s thoughts, especially of people with whom they were close.

“I will tell you a story, hijo, a cuento of a young girl you know well.” Putting her embroidery aside, she settled back into the pillow at her back and continued.

“When this girl was very young, she began to have disturbing dreams, dreams which frightened her because in the days that followed, they would almost always come true. More and more often as she grew, the dreams plagued her. And her abuelito, the only one who believed her, died before he could explain the gift she had inherited from him. She learned to keep the dreams secret because whenever she told anyone, they looked at her as if she were loca. And people, ignorant and afraid, had started to think she was either crazy or a witch.

Years passed, until one night she saw her father in her dream and knew what real fear was. In her vision her father was being dragged by horses in the field he was plowing, his leg entangled in the reins behind the arado.”

She paused, taking her sack of punche from her pocket to roll a cigarette.

I squirmed restlessly on the bed. From past experience, I knew that it was an effort in futility to urge her on, for if prodded to finish a cuento before she decided she wanted to, she was known to teach me a longer lesson in patience, sometimes making me wait for days, or until I had even forgotten the beginnings of a story and her teasing reminder would set me off, begging for the end.

I had to hand it to my abuelita; she knew how to build up the suspense in her stories like no one else. I was forced to wait as she took a laboriously long time rolling her smoke, her eyes twinkling with mirth at my discomfort.

“Where was I?” she asked, striking a wooden match on the sole of her shoe.

“Oh, yes, the dream.” Puffing a small stream of smoke, she continued, “The next morning, much to her dismay, the girl’s father had already begun to plow the fields when she awoke. Without breakfast, the girl ran out of the house, straight to the field.”

When she paused to puff her cigarette again, I could have screamed from the suspense; it was killing me. “Now, the neighbors had honey bees,” she reminisced, “and the hives were just across the river. For some reason, I never knew why, they swarmed—and the girl’s father with his horses were right in their path. It was a good thing the girl got there when she did, for her father, strong though he was, was already struggling to keep the horses from running away with the plow. When she looked down, the girl saw that the end of one of the reins had tangled around her father’s leg, just like in her dream. And just as the panicked horses took off, shaking the bees from their heads, she jumped forward, unwrapping the rein just in the nick of time to save her father from a very bad injury—perhaps even death.”

Gramma puffed at her cigarette a moment before she added, “That was the day the girl finally realized that her dreams were not the curse she had thought they were all along, for years having been afraid that perhaps she was a witch and that she had dark powers from the devil. They were forewarnings, a gift from God, and she had learned to read their meaning to help others.”

Putting her cigarette out, she looked at me closely, searching my eyes for understanding. “Sí,” she said quietly, “I have been called bruja many times, hijo, but only by the ignorant or the envious, God help them. They do not know that what I have is a gift from God and that I have learned to use my gift to avisar or to give consejo to those I see in my dreams.”

I breathed a sigh of relief, knowing that no matter what happened in the future, I would never suspect my abuelita of being a witch again. And I understood that my father possessed a different gift, a power to read my thoughts and to respond in the voice of my conscience to guide me in the journey of life. But at the same time, I was troubled. Hadn’t I also inherited such a gift, a power to see or hear things others didn’t?

I knew she picked up the apprehension in my eyes, for my gramma said softly, “No te preocupes. Do not be worried, hijo mío. Instead, thank the Lord that you have something not many people do and learn to use your gift to help yourself and to help others if you’re able. And if your friends question your intuition, you do what your conciencia tells you. If they are real amigos, they will look to you for consejo. Advise them well. If they are not, then you will have to live with their suspicions and their accusations just as I have. And though it will be hard, you will have to learn to leave them to their own consciences.”

I nodded, and we sat in companionable silence for a while. My gramma took up her embroidery again as my mind digested the importance of her story, her counsel. I knew that I would have to find within myself the strength to overcome my disquiet, to listen and watch for any avisos in the future, to use my gift of intuition wisely.

Suddenly remembering what I had seen the night before, I asked, “Do you believe there really are witches?”

“¿Por qué?” she asked, looking at me quizzically.

I described our encounter with the ball of fire and what Berto had done as it had fled.

She nodded, “There are many, including myself, who have seen them. And since there is no explanation for the balls of fire, there are many who believe that they are witches. No one knows for sure. But it has been a long time that any have been seen around here.”

“What do you believe?” I asked, a little uneasy about her answer.

“I believe that there is a power of good, which is God. But the Bible tells us that there is also a power of evil. Just as Dios gives His children gifts which help them to live as good Cristianos, then so could el Diablo guide those he chooses with the powers of darkness.”

She crossed herself before she looked at me for a moment. “That you saw one during la Cuaresma disturbs me. This is one of the most sacred seasons of the year. If it was a bruja or some other work of el Diablo, then they seem to have no fear that this is Lent, and today is Viernes Santo, the day our Savior died.”

“What could it mean?” I whispered.

The heavy silence of our thoughts spoke volumes, for we both knew that this afternoon La Procesión de Sangre de Cristo, the procession of the Blood of Christ, in which a chosen Hermano would carry the crucifix from the morada on his back, would be enacted. And even though the Penitente would not be crucified, the re-enactment of the most sorrowful day in the life of our Savior would take its toll on the Brother who played the crucial role. I wondered if it would be the Hermano who had portrayed Christ the night before in la Procesión de la Santa Cruz.

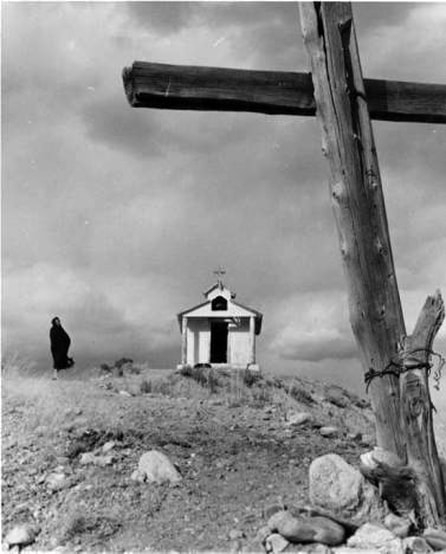

la bandera; Miguel's house in the background.

“What do you think happened to her?” my mother asked, looking from my grandmother to me and back at her again.

My abuela’s face mirrored my thoughts: a bruja! Could the one who had protested the most loudly that she was surrounded by witches and lunatics in fact be a witch herself? Could Berto’s rock have met its mark on the floating ball of fire, leaving in its stead a wound in a witch that would cause her death?

I knew that neither my abuela nor I wished the woman harm, yet I saw in her eyes the question I felt in my heart. If the woman died, then would the significance of the ball of fire we suspected be dispelled by her own death?

Unable to rest and unable to sleep, I rose when Berto appeared at my door about noon, sent to see if I was well enough to go to the morada before the procession began. At first my mother protested, having heard of my induction from my father earlier that morning. But rising unsteadily, I assured her that I felt better and that if los Hermanos had sent for me, surely I was needed at the morada. Physically, it was the truth, for my chills had subsided and I was no longer dizzy, but my mind whirled with questions and an impending sense of doom.

Concerned about how Berto would react if he heard of what had happened to the Lunática from someone else, I broke the news to him gently. Though I tried to convince him that we didn’t know whether the woman was only an innocent recluse who had fallen, perhaps even attacked by a thief (which was unheard of in our community), I heard the doubt in my own voice and saw the disbelief in his eyes. Berto remained convinced that the woman was a witch and that she had been injured by his hand, the hand which had cast the stone.

He ran his fingers through his shock of hair again and again, upset about her probable revenge. I, too, worried for Filiberto, remembering my grandmother’s words.

When we arrived at the morada, the Hermanos were resting beneath the shady cottonwoods outside. I went from one to the other exchanging greetings, touched by their concern. My father beckoned to me, moving a little away from the others so we could speak in private. He asked if I was up to the long hours ahead.

After I assured him I felt fine, he told me what had been decided during the morning in my absence.

When he told me who would be the Cristo in the procession of the afternoon, I frowned. My Tío Daniel who had been chosen for the honored role the night before had asked for and received permission to again portray Christ in the reenactment of His walk to Monte Calvario. I needed to tell my father about the premonition of impending death I sensed, but there was no way to explain without beginning with the ball of fire the boys and I had encountered the night before. So I took a deep breath, plunged in, watching his eyes widen when I told him what Abuela and I had discussed, and finished with the account of the neighbor woman’s mysterious injury. I breathlessly waited for his reaction.

He took it all in, quiet with thought before he spoke. “I am glad that your abuela explained about what it is to be a gifted member of this familia,” he said, “for from now on you will listen more closely to your intuition to guide you on the right path in life.”

“But that’s just it,” I blurted, “I have a queer feeling about what gramma said about someone dying. As much as I don’t like that lady for how she treated gramma, I don’t wish her dead, but if she does die, at least that might mean Tío Daniel won’t.”

“Perhaps Mamá is right,” he said. “I trust her judgment,” he added, laying a hand on my shoulder, “as I also trust yours.”

He stood, and I felt a surge of pride that he spoke to me as one man to another.

I waited for him to say that the procession to follow would be canceled or that he would put it to a vote of all the Hermanos, but when he spoke I knew that it wasn’t something he had the power to do. The rites and rituals of the Penitente Brotherhood were clear, and the reenactment I dreaded would proceed as usual.

“We will do what we must,” he said with determination, “and we will pray that Daniel will not be the one who has to die with Cristo tonight.”

We walked together back into the morada where the rest of los Hermanos were in prayer. The window, covered with a dark cloth, let no welcome warmth or light into the room. In the chill of the thick adobe walls there were only the flickering flames of candles to shed a wavering glow on the altar and the men kneeling before it. As we joined them, I took the crucifix I had finished carving, painted black the day before, and placed it among those of my Brothers and the small covered santo Pedro had carved.

Kneeling, I waited for the peace I always felt when I prayed there. I longed for the solace I would have received if I were able to look into the face of the Savior. But every retablo, every santo, was covered in shrouds of black. I felt a sense of loss, of foreboding—until I closed my eyes. From the dark recesses of my mind the face of Christ emerged, filling me with strength to face whatever might occur.

It was a little before two o’clock when we emerged from the morada, blinking our eyes in the welcome light of the sun, warming our stiff bodies in its rays as we were surrounded by the friends and relatives who had come to join our procession. Women bustled into the cocina with pots of food while others entered the prayer room for a moment of contemplation before we began.

I greeted my mother and grandmother with a hug, reluctant to let either of them go, for in their arms I felt the comforting reassurance of my youth. I found myself close to tears, realizing that the innocence of my childhood was lost to me, only to be remembered in their embrace with the bittersweet knowledge that I had willingly forsaken the child within me and let the man in me emerge when I took the vows of a novicio.

Collecting myself as best I could with the tumultuous emotions and frightening premonition looming over my thoughts, I made my way over to the boys who were resting beneath the trees, knowing if anyone could take my mind off my worries, it would be the gang. Horacio was speaking as I joined them.

“My gramma told me a cuento once,” he said quietly. “She thinks it’s only a legend though, ’cause she never really heard of it happening in her lifetime.

Her own abuela told it to her when she was a girl. Do you wanna hear?”

Berto nodded. “Anything, if it’ll stop me from thinking about the bruja.”

We all looked at Berto sympathetically, wishing we could relieve him of the burden of his fears and knowing there was nothing we could do except keep his mind off them.

Horacio began, “Well, you know how Tío Daniel is going to play the Cristo and carry the cross on his shoulders in a while?”

“Don’t remind me,” I waved a hand at Horacio to continue when the boys’ confused looks turned on me. I was thinking of my uncle’s nightmares about the war and wondering if this was his penance for some unimaginable act.

“Anyway,” Horacio continued after looking at me askance, “my gramma told me that one of the descansos up there,” he pointed his chin to the mountains beyond the church, “is supposed to be a real grave, the grave of an Hermano who died while he was acting the part of Christ.”

We gasped. Pedro added, much to my discomfort, “It could be true, you know. I heard my papá and my grampo talking once, and they said that in the old days the one who played Cristo was really crucified on Viernes Santo, only instead of nails, they used ropes to tie him to the cross.”

I was unable to shake off the chills that rose up my spine. Though I noticed the others squirming as well, I knew my distress for my uncle was greater than theirs because they had no knowledge of my conversation with my grandmother.

“All I know is what gramma told me,” Horacio finished, leaning toward us. “She said that if it was true, then the Hermano who died would go straight to heaven. In those days, no one was allowed to witness the procession, but what was stranger was that the dead man’s shoes were left on his doorstep so that the family would know how he had died, and for a whole year no one but the Penitentes knew where they had buried him.”

We all took this bit of news in silence. I pictured the scene Horacio described and thanked the Lord silently that we didn’t do things the old way anymore, and then Pedro spoke up as if reading my mind.

“I’m glad we don’t do it that way anymore.”

We all agreed. However, as we rose to join the men already getting into formation, I saw the black crucifix carried on the shoulders of two Hermanos who emerged from the morada. The moment for which I had longed for so many years—and only today had come to dread—arrived. For the first time, I would take part in the procession of Penitentes, but the pride I felt was overshadowed by the knowledge that my uncle, whom I loved like an older brother, would be in the lead carrying the heavy cross. I knew my eyes would be upon him all the way. Coupled with my foreboding that someone would be dead before morning, my first procession became a penitence indeed.

I sighed heavily, lining up with Pedro at the rear of the group. As everyone who gathered to join the procesión took their places behind us, I was surprised to see Primo Victoriano, leaning heavily on his bordón, directly behind me with his wife, Prima Juanita. I noticed Berto and the others positioned behind him, ready in case he needed assistance.

I turned and offered the elderly man my hand. “If you get tired, everyone will understand if you have to stop,” I told him in a whisper.

“I will,” he promised. “I just had to come one last time, you understand?”

The longing in his withered face was enough to tell me that this might be the last Lent he would see in his lifetime, that this might be the last chance he had to join his Brothers before age or ill health took its toll.

I nodded in understanding, but I saw the weariness of his eyes, in the way he leaned on his cane, in the way his breath emerged from his mouth in short, tired gasps. “Don’t overtire yourself, primo,” I warned, but he only waved my concern away with a hand.

The procession began when my father’s voice rose to announce that this was the reenactment of the Passion of Christ. My Tío Daniel, the massive black cross on his shoulders, moved forward, setting the pace for us to follow.

“Oh—ohhh, imagen de Jesús doloroso para ejercitarse en el santo sacrificio de la misa como memoria que es de tan sacrosanta pasión,” my father intoned, telling us to imagine our dolorous Savior fulfilling His destiny in such a sacred sacrifice in our reenactment of the memory of such a sacrosanct passion.

I read along as the rest of the Hermanos joined in, my voice blending with the varied pitches of the men, rising and falling with each line. The music emerged as if from our very souls to waver and float around us as we spoke to our Savior in a somber hymn rather than with mere words. The very tone of our combined voices and the reverence with which we sang spoke volumes as our words conveyed how much we believed in the passion of our Savior.

My father’s words conveyed that Jesus had revealed many times to his faithful servants what was to follow. And though no one actually did the things to my uncle that my father told us, he paused with each recitation, and the weight of the words he spoke with such tremulous emotion made us feel that just by describing the terrible things done to Christ he felt them in his heart as he carried the symbolic cross.

Then the first time he stopped, Tío Daniel spoke loud enough for all to hear the words that indeed seemed to be the words of our Savior: “Primeramente me levantaron del suelo por la cuerda y por los cabellos viente y tres veses.” My uncle revealed, “First they lifted me from the floor by rope and from my hair twentythree times.”

As he resumed the pace for the procession to follow, my uncle paused twenty-one more times. His pace slowing with each pause, Daniel fought the trembling of his legs. I saw his shoulders bend under the cumbersome cross, symbolically weighing heavily in our hearts each time he staggered under its massive bulk. Even from where I stood, with twelve men before me, I heard his breath come more heavily, his voice emerged more tremulously, the words quaver as he described the countless terrors suffered by Christ in His passion.

“They gave me six thousand, six hundred, sixty-six lashings of the whip when they tied me to the column …. I fell on the earth seven times … before I fell five times on the road to Mount Calvary …. I lost one thousand twentyfive drops of blood.”

By the time we were halfway to the church, many of the women were sniffling, wiping their eyes with their kerchiefs. But the worst was yet to come as my uncle continued, weakened but undeterred in fulfilling his role.

“They gave me twenty punches to my face …. I had nineteen mortal injuries … they hit me in the chest and the head twenty-eight times …. I had seventy-two major wounds over the rest.”

By this time some of the women were weeping openly, and the smaller children, frightened beyond belief—I knew because I was at their age—began to sob quietly at their mothers’ distress. Primo Victoriano stumbled behind me, and I stepped back to grasp one elbow as Berto took the other. The determination in his face to reach the capilla, to finish the procesión as an Hermano one last time, was heart-wrenching. And as I took some of the weight off his feet with my support, I felt tears gather in my eyes.

“I had a thousand pricks from the crown of thorns on my head because I fell, and they replaced the crown many times,” my uncle’s weakened voice continued.

“I sighed one hundred nine times … they spat on me seventy-three times.”

The tears flowed down my face. I heard Primo Victoriano’s labored breaths at my side. I thanked God the procession had come to an end, for the words were too painful to bear, humbling our Christian souls to the core of our being.

“Those who followed me from the pueblo were two hundred thirty,” my uncle finished, “only three helped me …. I was thrown and dragged through barbs seventy-eight times.”

As we reached the capilla, my uncle was barely moving, his feet shuffling wearily in the dirt, his breathing labored. When he leaned precariously forward, the cross threatening to smash him into the earth, several women cried out in alarm. Leaping quickly to his aid, my father and Primo Esteban each grabbed an end of the beam lying on his shoulders, relieving him of his burden just as his knees buckled beneath him and my uncle fell to the ground on hands and knees.

When I saw him fall, his face grimaced in pain, my heart throbbed in fear that he could be gravely hurt, that my premonition of an impending death would come true. I would have rushed to his side but for Primo Victoriano, whose arm clutched mine tightly, his shoulder leaning heavily against me. If I left him, he too would fall.

All the women were now sobbing as they looked at my uncle, trying in vain to stifle their uncontrollable cries because of the children, who, too young to understand what we did, cried with distress and sympathy for their mothers’ tears. A few of los Hermanos rushed to help my uncle to his feet, supporting him as they took him into the church. Though he was exhausted, my tío appeared to be unhurt, and a collective sigh of relief shivered over us. The women calmed themselves and mothers or older sisters hushed children’s cries into soft whimpers.

Primo Victoriano continued to shake against me, his legs quaking with his effort to remain standing, his breathing heavy. Beginning to falter under his weight, Berto motioned for Pedro to help us, knowing that my scrawny frame wouldn’t be enough help to get the elderly man into the church. Relieving me quickly, they placed our primo’s arms over their shoulders, supporting his weight between them as they moved slowly into the capilla with his wife at their side. Following with Horacio and Tino, I heard Primo Victoriano mumble disappointedly at himself that he had no strength left to light the fire or the candles inside. Exchanging glances and nods, we hurried inside, so that when our Primo reached the door, I was busily feeding the flames of the kindling I had lit in the stove and

Horacio and Tino were moving from candle to candle quickly. Turning as he entered, I smiled, glad that we were able to relieve him in his duty now that he needed us. Primo Victoriano only nodded, but the gratitude in his eyes said it all before he allowed the boys to settle him comfortably in the pew nearest the stove.

When the Estaciones ended that evening, there was a silence unsurpassed by any service we had yet attended. I knew that for those who prayed with los Hermanos it was in part because of the anguish of witnessing la Procesión de Sangre de Cristo and the terrible sorrow of las Tinieblas that was to come back at the morada afterward. For Pedro and me, it was something more. We knelt with los Hermanos as novicios in the center aisle of the capilla as we made our slow and somber revolution of prayers and alabados around the retablos of the Stations of the Cross. I found my place in my faith, and it affected me as nothing before had done. It was awesome to contemplate.

When my father signaled that it was time for our return to the morada, I retrieved my black crucifix from the altar. I blew out a candle with a fervent prayer for my uncle’s health and took another taper with me to the door of the now darkened church. Spotting Primo Victoriano, supported between his wife and Berto’s mother, I went to say good night. Someone had gone for a wagon to take the elderly man home, Prima Cleofes explained, for he felt tired.

Prima Juanita clucked her tongue at her stubborn husband, but he didn’t need to say a word. The soft smile that lit his face told me that he had done what he had set out to do. He was content that he had accompanied his Brothers one last time, and he would toll the bell also for the last time that night before he would allow himself to be taken home.

When I saw los Hermanos taking their places in the center of the road, I bade him good night, telling him to rest and not to worry, I would be there to help him on Easter Sunday as well. In the soft glow of the lanterns and candles, his eyes grew moist.

Blinking back his tears, Primo Victoriano looked at me gravely. He said, “I will be here on Sunday, hermanito, and you will light the candles for me, but I will not see their light. I will not feel the warmth of the fire you will make.”

Confused by his cryptic message, I searched his eyes. From the quiet contentment and resoluteness of his gaze, a silent tear that rolled down his withered cheek and touched my heart. My respect and admiration for the elderly Hermano who had fulfilled his desire engulfed me. On impulse, I hugged him close for the first, and for what would also be the last, time in my life.

near Chimayo, New Mexico

Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA)

Negative number: HP.2007.20.562

El Hermano:

A living link to a way of spiritual survival

El Hermano, a first novel by Carmen Baca, brings to life through the story of a young boy in late 1920s New Mexico, the wonder of Los Penitentes, who have been painted by rumor and misconstrued in fiction as backwards and brutal, as cult rather than a humble brotherhood of Catholic men. El Hermano could have been the story of my own great-grandfather, a Penitente brother who died a few years before I was born and thus I know as little of him as the brotherhood to which he belonged. Both the shed on the family ranch and the chapel he built down the road where perhaps he carried out some brotherhood rites still stand and have been objects for reflection on his life and Los Penitentes for me for many years.

The valleys and mountains where northern nuevomexicanos or hispanos live can be out of the way, sparsely populated areas. Due to this remoteness the Penitente Brotherhood arose out of necessity. When Mexico gained independence in 1821, the priests were recalled to Spain, and communities like this farthest colony of New Mexico were faced with a long journey to seek absolution of sin. There were already traditions of lay brotherhoods dedicated to saints (and it is said some of them in the New Mexican colony were covers for Crypto-Judaism).

Men of the community took it upon themselves to absolve their own sins, so that they could address the sins of the community as well. Their activities included praying, procession, scourging and, at one time, electing a member to be crucified.

Los Penitentes have been a secretive and humble brotherhood. The secretiveness and perhaps lurid nature of the scourging and crucifixion had gained interest in the U.S. in the turn of the 20th century. Penitente practices were portrayed in Brave New World, and I recall as a teenager my Anglo classmates mocking the rituals. I chose not to mention to my classmates that my great-grandfather belonged to the brotherhood. Books on American cults, placed next to Ripley’s Believe It Not!, misconstrued the practices of the brotherhood and showed turn of the century anthropological photos of the crucifixion ritual that was no longer practiced.

One such book even had a “Fernandez Brother” chapter that depicted the “ghastly” activities of some of my relatives that took place more than a hundred years ago. While I have spoken to a Penitente brother and a santero, an artist who carves or paints traditional religious figures, who repaired their moradas, the small churches where the brotherhood worships, their responses rather than “secretive” seemed topics “too personal to discuss.” The brotherhood remains a practice that I have known little about.

There has been a need for humanizing countering the negativeportrayals of the brotherhood, which is a living tradition. And the novel El Hermano doesn’t indulge in the lurid portrayal of flagellation or crucifixion by the Penitentes and does an excellent job in portraying members of brotherhood as a religious people concerned for their community and their spiritual needs.

In the 1920s, the young boy, Jose, and his friends in between going to school and doing chores, wonder what the brotherhood is up to behind the walls of the moradas. They grow anxious as the time nears to join the brotherhood if they prove themselves worthy. Their spying gains the attention of Santa Sebastiana, the New Mexican version of La Muerte (or Santa Muerte), who warns them not to spy upon the brothers.

The boys in their nightly attempts to spy, see other apparitions, and a ball of flame that could be a witch. Their elders counsel them and tell them stories to help them dispel their fear of Santa Sebastiana (fear life and its chance to commit sin, they say) and their approaching adulthood and the spiritual responsibilities of being a part of Los Hermanos begin to take shape.

Earlier on, Jose also worries about the looks of his indigenous nose. He wonders if it is ugly though eventually he accepts it as many people in his family also possess the nose. Not only is it common for teenagers from everywhere to worry about their looks, mestizos worrying about their indigenous features often comes up in U.S. literature and in the journey to accept themselves.

My sister and I, very young and not realizing what we were doing, would accuse each other of having a nose more like mom’s and run to the mirror and push our hawkish flared native noses down to no avail. The nose moment is a good example that El Hermano is a serious book about serious issues—how to be good, whether to defy elders, how to live in the face of death, and faith—it may serve as a Young Adult book but isn’t limited to that genre.

El Hermano is also a historical book—set in the late 20s just before the Great Depression. (Jose says he and his family were already too poor to notice). Eventually, the story follows Jose into the war effort of World War II and to the 1970s. As one of the last hermanos in the valley, he must watch and endure as the order ends.

The rural New Mexican setting and the coming of age of a young boy might bring to mind Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless Me Ultima, but El Hermano is set farther north and is at least 10 years before the confusing times of young soldiers returning home from war and allows focus on the Penitentes. The boys are also different: unlike Antonio, Jose doesn’t question his Catholic faith and is overeager for his acceptance into the brotherhood.

Though characters in El Hermano do not challenge traditions overmuch or get involved in deadly conflicts, they have the conflict of concern for their souls and leading a good life. Though El Hermano searches for answers (and may have a witch), it concentrates more on day to day rural life rather than the many questions of survival and witches at odds with curanderas, as in Bless Me Ultima. The focus is on Los Hermanos and Jose’s eagerness to join them, which makes for a different though not less enjoyable story.

The writing of El Hermano is excellent, not overly ornate, but smooth and easy to read. The story is compelling, the tension of what the boys may find, what the vision of La Muerte means, keeps one reading. The acceleration of the story to tell the whole tale of the main character’s life outside the focus of events is done well, and Jose’s testimonial at the end as an older man wraps the story up nicely.

In the afterward, the author lifts the veil. After her father’s passing, as he was the last brother, she inherited her father’s trunk that contained everything used by the brotherhood for their rituals. It was a revelation for her and seemingly an impetus to share this story.

Though the father’s local sect died out, the author has enabled us to see the brotherhood in a new, more honest light rather than as sideshow cultists and moreover honors and sets as examples her hispano forebears. One need not be hispano, Chicano, or Latino to appreciate this book, but for me as a nuevomexicano on the periphery of the Penitente Brotherhood, author Carmen Baca has revealed insights to traditions and a living link to those men who created a way of life for spiritual survival and provided a better understanding of a great-grandfather I have never met.

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

April 2024

March 2024

November 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

December 2021

November 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

December 2020

September 2020

July 2020

November 2019

September 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

February 2010

Categories

All

Archive

Aztec

Aztlan

Barrio

Bilingualism

Borderlands

Boricua / Puerto Rican

Brujas

California

Chicanismo

Chicano/a/x

ChupaCabra

Colombian

Colonialism

Contest

Contest Winners

Crime

Cuba

Cuban American

Cuento

Cultura

Culture

Curanderismo

Death

Detective Novel

Día De Muertos

Dominican

Ebooks

El Salvador

Español

Español & English

Excerpt

Extra Fiction

Extra Fiction Contest

Fable

Family

Fantasy

Farmworkers

Fiction

First Publication

Flash Fiction

Genre

Guatemalan American

Hispano

Historical Fiction

History

Horror

Human Rights

Humor

Immigration

Indigenous

Inglespañol

Joaquin Murrieta

La Frontera

La Llorona

Latino Scifi

Los Angeles

Magical Realism

Mature

Mexican American

Mexico

Migration

Music

Mystery

Mythology

New Mexico

New Mexico History

Nicaraguan American

Novel

Novel In Progress

Novella

Penitentes

Peruvian American

Pets

Puerto Rico

Racism

Religion

Review

Romance

Romantico

Scifi

Sci Fi

Serial

Short Story

Southwest

Tainofuturism

Texas

Tommy Villalobos

Trauma

Women

Writing

Young Writers

Zoot Suits

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed