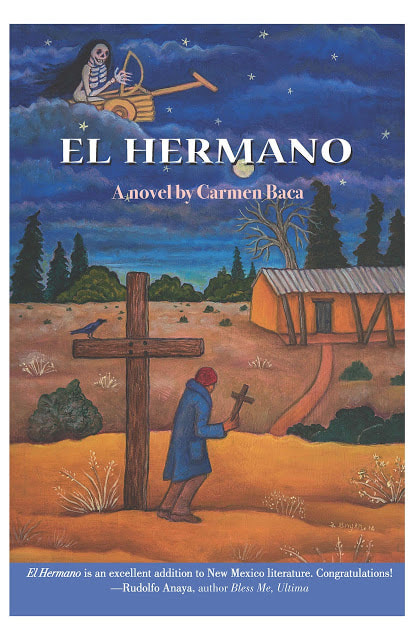

3rd PlaceSacred Evolutionby Carmen Baca With roots entrenched in the mountain I called home at the edge of the Sangre de Cristos, I surveyed my surroundings from near the top. My many limbs reached to the skies on sunny days or cold, snowy ones for so long I had no concept of my age. All I knew was that I had evolved from sapling to mature adult over many revolutions of the sun and moon. Seasons mattered not, not for my brethren and me. Our purpose was to grow, to provide shelter to those who needed it, and to give sustenance to all living beings. We were the sentinels, the giants of the forest. But we, too, felt fear. Nature’s wrath threatened us in the annual spring winds. We bent so far from side to side we feared we would snap in two. “Hold fast!” I cried to my fellow giants. “HOLD FAST!” they called, their voices echoing from mountain to valley and each peak beyond. We held steadfast to the earth, our roots clawing into the dirt and around buried stones to keep our balance. Our size would have broken our smaller brothers, our offspring, and even ended the lives of forest creatures had we fallen. We stood tall. The droughts that sometimes came after increased our peril during the spring thunderstorms which followed. Dry lightning ignited one of us once on a distant ridge. We watched in horror as one of our brother’s trunks exploded and his limbs caught fire, the flames growing and spreading to his neighbors until a wall of vivid red and brilliant orange spread and covered that mountain top. Black smoke rose high, turning gray as it wafted toward us. “Oh, no,” the smallest of us, the saplings, cried. “Remain strong!” my brother beside me called. “REMAIN STRONG!” each tree in the forest shouted. The echoes gave support to those of our brethren already covered in fire and to the others who stood until they could no longer. The inferno pulsed with a life of its own, its breaths made stronger by the fuel feeding it. The roar of destruction reached us even though we were in no danger then. We feared fire like we feared nothing else, and we quaked deep inside ourselves because we knew as big as we were, as strong as we stood, we were no match for it. We watched for so many passings of the days into nights that we worried they would never end. That all-consuming firestorm ate everything in its path. Only one ridge lay between the devastation and our mountain when man came to our rescue. We were safe—for now. We mourned for those of our kind and for the animals who used them for harbor and home. So many had succumbed to the conflagration. The reminder of the tragedy stood before us for many more passings of the sun and the moon. Those dry, dead pillars stood tall until the winds came again to knock them over. The sounds of the cracking, decaying trunks reached us in the silence that came thereafter. We cringed, our boughs shaking in sympathy. And we shut our eyes at the last horror they endured as mankind did: from dust they had emerged and to dust they returned. Time passed, with more spring winds and fall fires, but our mountain was spared. I never wondered why, but now I speculate perhaps because of what I am now. Springtime returned and with it came the men again. Others followed, bringing loud apparatuses on tracks and large wheels, creating roadways which crossed our mountain. The monstrous machines felled many of us with precise efficiency, and we came to understand our purpose had changed. Some of us were destined for unknown intent because man had determined we could be used to benefit him. We continued to stand tall, and we understood some of us would be cut down. We did not know which among us would be next, but we all clung to the hope that whatever our futures held, our ancient frames would be used for noble causes. I watched many of my brothers fall into the jaws of those massive machines. Afterward, I stood alone in what was now a glade, and I wondered why I had been spared. Many more times the sun and moon traded places in the sky, until the day my turn came. No large, rumbling devices appeared on that early morning. Instead, two wagons arrived, pulled by draft horses and accompanied by a group of men on horseback. They halted in that clearing and stood looking up at my massive trunk. They spoke among themselves words I could not hear from my height, and they must have determined I was right for their plans, whatever they were. Two men approached with a long blade I later learned was a two-man crosscut saw. Several more with axes stood by. I felt a vibration close to where my trunk rose from the earth and my limbs trembled with the back-and-forth cutting motion of the men manning the tool. I expected more sensation, something I didn’t know the name for but something dreadful. But the severing of my body from my base, though it took some time due to my width, occurred with no more than an increase of that forceful reverberation deep in my core. Then I fell. I struck the earth with my massive frame, several of my branches breaking with the impact. My trunk shuddered a bit after the fall and then I was still, my view from the ground novel and unexpected. The men took to their axes and dismembered me from top to bottom, some of my trunk left long while other sections were cut short. The part of me that was capable of understanding was lifted into the wagon along with other pieces. After the two wagons were filled, we traveled down the mountain and reached a small hamlet in a valley I had only seen from high above. A large dwelling, our destination I discovered, provided cover for me for another period of the sun chasing the moon and creating light after dark. When I was handled again, it was through a machine which trimmed me and turned me into what the men called lumber. My evolution had begun. And though I pondered over the final product that would come from my frame, I harbored the hope that it would be noble, worthy of the sacrifice of my entire physical being to it. # Fifteen-year-old Matías José de la Cruz, apprenticing as a carpenter with his uncle, ran his hands over the lumber in the family sawmill, gauging which of the newly created boards would more suit his new project. Selecting those his hands found smooth yet supple, good for carving, he loaded them onto his father’s wagon and deposited them across two sawhorses in the shed he used for his woodworking. As young as he was, his reputation grew with the few items he had made for friends and family: a kitchen table, some chairs, a workbench, simple projects which hadn’t presented any challenges. This one was not difficult to make either, but it would be his most important, most worthy of expert talent and extraordinary touch. He would transform the lumber into a crucifix, one of the most sacred of symbols of their faith. He had chosen the most majestic, prodigious pine of the forest. He smiled as he ran his hands down the smooth wood and envisioned it evolving from what it was now to what it would become. The project had been requested by his father, el Hermano Mayor, the highest-ranking brother of the lay confraternity known as los Hermanos Penitentes, the Penitent Brothers. The brotherhood, existing in some Spanish-speaking cultures around the world, was especially active in northern New Mexico in the early nineteen hundreds. Known for their leadership of rural communities in both service and religion, they also piqued public interest because of their spiritual rituals enacted behind the locked doors of their moradas, prayer houses. Because non-members were excluded, sensationalistic rumors spread that they did unspeakable things in the name of self-penance. On Holy Thursday every Lent, one brother played the part of Christ and carried the crucifix from the morada to the cemetery where the road was lined with descansos, small pillars of rock, for each station of the cross. This re-enactment, attended by the community, played into people’s imaginations about what los Hermanos did to themselves on those Lenten nights behind closed doors. The cross they had carried until now had exhausted its purpose after decades of use, which was why Matías’ father wanted a replacement. Matías knew his creation would be the focal point of everyone’s eyes on that Jueves Santo, and he was determined it would be his best work yet. Nothing could be more sacred, though carving his own cross to carry in processions when his time to be initiated into the brotherhood would be a close second. Every day after school, Matías retreated to his shed to work on his project, talking to the seven-foot-long and heavy board that would be the pillar the Hermano playing the part of Christ would carry on his back. “You will be a masterpiece,” Matías told the post. “You will play an important role in the brotherhood’s processions. You will draw the eyes of everyone.” He didn’t know his words penetrated the very heart that was left intact of the original giant of the forest. The heat his fingers felt coming from the wood as he rubbed it smooth with sandpaper he attributed to the friction. He didn’t know the lumber vibrated inside with the pleasure it retained from knowing it would have a special purpose. Matías took his time fashioning the cross with his special touch and attention to detail, hand-carving scenes from the stations along the front and back of the cross-sections. No one had asked for these features, but he answered a compelling need inside himself to supply los Hermanos with a crucifix worthy of them. To Matías, los Hermanos deserved his reverence. He felt they were the closest to the apostles any human on earth could hope to reach. His self-doubts about his worthiness to become one of them became the conflict he struggled with internally and most intensely over the past year. He knew his time was close to becoming one of them, but he couldn’t see himself as deserving of the honor, not with his flaws. Right before Lent, Matías called his father to the shed and showed off the finished product. Señor De la Cruz, tears brimming over, could find no words to express what his heart felt at the sight. The workmanship of his son’s artistry would suit the brotherhood’s needs for many years to come. “Bien hecho,” el Hermano Mayor said, looking close up at the intricate details of the scenes etched into the wood. “We will have the padre bless it next time he gives mass.” Matías nodded, but inside his body quaked with the approval in those two curt words: Well done. A second later, the unspoken question in his father’s eyes turned him cold: Will you be ready to join us this year? Matías watched his father carrying the crucifix over his shoulder to deposit it in the wagon for the short ride to the chapel midway between the cemetery and the prayer house where it would stand in a corner to await its blessing. The voice in his head echoed the question. Will you? It will symbolize your emergence into manhood from childhood. Are you ready? # The double doors of the capilla closed, pulled shut by the hands of el Hermano Mayor, the lock clicking into place before he removed the key. The interior lay in the muted sunlight coming in through hand-made curtains with crocheted hems. I came to awareness there in an atmosphere of silence meant for introspection and devout prayer. I stood to the right of the entry beside a large bin of wood filled and ready to feed the box stove in the center of the space between door and pews. A wide aisle between two columns of wooden pews led to the altar. Saints, crosses, candles, and statues of Mother and Child, Mother holding dying Son, and various other religious relics stood in no particular pattern. The rustic simplicity pleased me. There was a sacredness to the place, a peace I missed from when I towered atop the mountain. The day I was brought down, I ascertained I was now at the bottom in the valley I had viewed every day. Day after day, the young man laid his hands on me in one way or another, with a small ax and wood carving tools, sandpaper, a soft cloth. His confident touch gave me no apprehension. I knew whatever he did to me would be pleasing to the eye. The young carpenter spoke to me as he worked. I knew from his fastidious attention to detail and his scrutiny of his handiwork I was intended for a special purpose. I tried to make him feel the joy he gave me by exuding a warmth from deep within me. Day after day, I looked forward to seeing my visage in the reflection of his eyes. Where before I had been a round trunk of great size, then transformed into long blocks of wood, I was changed again into a cross, some symbol the people seemed to associate with their beliefs in the same power as I. The someone, the all-powerful who created us all. That realization gave me gratification deep in my heart, what was left of me. From a giant of a tree, I emerged as a thing of beauty, intricate carvings adorning my exterior, while the inside of me remained unchanged. I had been grateful to be alive in the shell I had been given and in that place where I spent the first century of life. I was now overjoyed to be of service to man as a symbol of hope for them for however much time I had left. The heart of me which had been carved by the young man’s hands rejoiced for myself. But my keen sense of empathy allowed me to read into his eyes. They revealed an internal conflict I hoped perhaps to influence into giving him the spiritual awakening he so craved. I had to try; we were bound, he and I. There was no putting it off. It was time for his evolution as it had been mine from the moment he had cut me down. # Matías accepted the congratulatory handshakes of the community, los Hermanos especially, that next Sunday morning when the parish priest came to give mass. The crucifix had been blessed and carried to the altar as a gift to Santo Niño, for which the chapel had been named. Each man looked him in the eyes as they gripped hands after the mass, and Matías knew they all shared the same inquiry as that of his father. The men lined up to take the cross from the capilla to the morada on foot. They walked down the dirt road in a procession of two rows behind Matías’ father carrying the crosspiece in the lead. They took turns moving up behind him, taking up the bottom of the long, heavy crucifix to lighten his load. He watched for a moment, picturing himself at the end of the procession. Then he left for home with a niggling reminder in his heart that before Lent he had to decide if he was ready for his initiation ceremony. The cold of February gave way to a warm spell on that Ash Wednesday, the day marking the beginning of Lent. The prayers at the morada held a special significance that year. Matías became an Hermano before the night was over. The initiation he had been anticipating with the dread of the unknown passed instead into an internal satisfaction with himself that he had accepted Christ as his Savior with a deep consciousness of what it entailed. Of course, he had been baptized and confirmed, but he had been only months old and ignorant of the significance. Even his catechism and subsequent communion ceremony had been somewhat superficial, a rite of passage he was required to undergo, with a slightly more depth of understanding as a teen. But becoming an Hermano set him apart from his peers. A certain respect and a reverence for what he represented made even his best friends heed their words and govern their behavior lest they disappoint him. Matías finally understood the significance of his emergence from boy to man. # Much time passed as I grew old and weathered. The delicate carving of biblical scenes on my crosspiece had faded with the constant touch of los Hermanos’ hands over the many, many trips of the sun and the moon. While I stood against the back wall of the prayer room in the morada for long periods, I was taken out for special ceremonies. I was the centerpiece of the brotherhood’s attention during a time they called la Cuaresma, Lent. I came to understand when the morada’s doors and windows remained open and the fresh spring breeze blew through the three rooms for that duration, and my core throbbed with renewed energy from the excited noise of the men, women, and children of the community. Each Lent I looked forward to a special day they called Jueves Santo when an Hermano carried me at the front of a procession from the morada to the capilla, the campo santo, and then back again. I was the center of every eye on this day, and I sensed my importance more, but not in a self-aggrandizing way. It was a deep honor to be a part of the community. I knew I symbolized something great, something beyond my ken. But this afternoon, with Matías now an old man at the edge of passing into the afterlife, carrying the cross despite his brothers’ protests, I sensed this day would end unexpectedly. The old Hermano bore the brunt of my weight on his shoulders and upper back, but it was made more bearable by his brothers. They shuffled along close by, shifting one out for the other after every Station of the Cross when they stopped to kneel in the dirt and pray. In this manner, each brother held the cross, three at a time beside and behind Matías, and all shared the burden of man’s sins as they walked. A short rest after they returned to the chapel preceded the brothers finishing the procession to the morada where they ate their last supper together and prayed behind the locked doors. I had seen the Verónicas who came when the men rested earlier to leave pots kept warm on the stove and dishes filled with food, the table laid, and the rooms spotless. The women’s society—the wives, mothers, sisters of los Hermanos—served as an auxiliary to the brotherhood with their own leader and rules of conduct. They were freer in their discourse around me than the men when they cleaned the prayer house, and I was privy to their thoughts more than those of los Hermanos. They and the rest of the community members were invited to attend the final ceremony marking Christ’s last day on earth. The people walked by lantern from their homes to the morada. I remember seeing this display of bobbing illuminations from the mountain top. Groups and lines of lights traveled winding paths, single shining dots joined them at junctures, and the large body of lights made its way to the morada where I stood at the front of the altar with Santa Muerte to my left. The carved effigy sat perpetually poised in a small picket fence enclosure with an arrow pointed at any who stood before her. She faced me across the room every day since my usual location was against the opposite wall from her. In the darkest hour of the night, the ceremony began with the lighting of thirteen candles placed along a triangular-shaped candelabra about five feet long standing on a four-foot-high pedestal. The candles, symbolic of Christ and His twelve apostles, illuminated the room with a soft, deceptive peace. We all knew the flames would be extinguished one by one, plunging us into the deepest black both physically and spiritually, evoking a most intense personal penance. This was the most horrible and holy of nights, Las Tinieblas, the Earthquake Ceremony. It took us all back in time to listen and to participate in our own ways. Each attendee, whether Hermano, a Verónica, or layperson, chose the method best for them to experience with most poignancy the night of Christ’s death. Following each prayer, the mournful chanting of the alabados, like dirges, sent chills up our spines. “Mother Mary, look at Your Son…see the cross on His shoulders…His body bathed in blood…His head crowned with thorns…His final day has come…” I felt the human pain as I envisioned the scenes of that day in the flickering of the candles on the walls. As though they cast shadows of those acts so many years before on the night of Christ’s death, those humans felt the pain of culpability which they projected toward me, the physical cause of their Maker’s mortal suffering. Since my evolution, I had felt revered by the community. Only on the nights in all those years of performing Las Tinieblas was I made to feel abhorrent. I deflected their pain, accepting the reverence they also felt deep inside. I was a symbol of death, but also of the redeeming Passion and resurrection. I stood tall as after each alabado, a candle was extinguished. The act brought more darkness into the room as though it physically and slowly wrapped a shawl over us all or perhaps a death shroud, I ascertained after this night. By midnight, we would experience His descent into hell when the last candle went out. The complete and utter darkness of the shuttered room, cloying with the scent of wax and incense, stifling with the fifty or sixty people crammed into the rooms—all contributed to the atmosphere of hell. The human wails and swift whooshes of whips, snapping and striking skin, the rapid turning of the multiple and different sized matracas, the noisy clackers, made the ears hurt. The cacophony symbolic of the chaos that is hell lasted only minutes, but always, always penetrated my heart, the heart of the tree I once was. Our internal pain made worse by the doleful alabados, sung by los Hermanos, sent many of the women into tears. The children cried because their mothers did, and I thought perhaps they too sensed the solemnity of the ritual in their own ways. Then by some unspoken signal I didn’t understand, all quieted. One by one, the candles’ flames brought light and peace into the room, kerosene lanterns were lit, children quieted at mothers’ shushes, and deep breaths restored life to the prayer house. Quiet conversation, some with nervous, shaking voices, commenced. Usually, no one lingered. The rooms were straightened out, the fires banked, candles and lanterns extinguished for the last time that night. The Hermano Mayor locked the door, and the humans left me alone again in the dark with la Muerte on her stool directly across from me. This night was an anomaly I hope I never witness again. Bittersweet with great sadness and joyful rejoicing, the end of another beginning had started sometime during our clamorous man-made hell. Matías had evolved for the final time. Santa Muerte had aimed and penetrated the heart of the old man. But it was I who caused his death. Although it pained me greatly to know I played a crucial role in transforming him, I acknowledged our connection had been inevitable. He had changed me for good, and I had repaid him by transforming him into something better. The wailing and the praying commenced. The fast preparations for the wake of the long night ahead ensued. I observed from my place in back of the prayer room, but I knew only the shell of the man remained. I knew Matías had already emerged from the morada with wings.  Carmen Baca retired in 2014 from teaching high school and college English for thirty-six years. Her command of English and use of her regional Spanish dialect contribute to her story-telling style. Her debut novel El Hermano published in April of 2017 and became a finalist in the NM-AZ book awards program in 2018. Her third book, Cuentos del Cañón, received first place for short story fiction anthology in 2020 from the same program. To date, she has published 5 books and close to 50 short works in literary journals, ezines, and anthologies. She and her husband live a quiet life in the country caring for their animals and any stray cat that happens to come by.

0 Comments

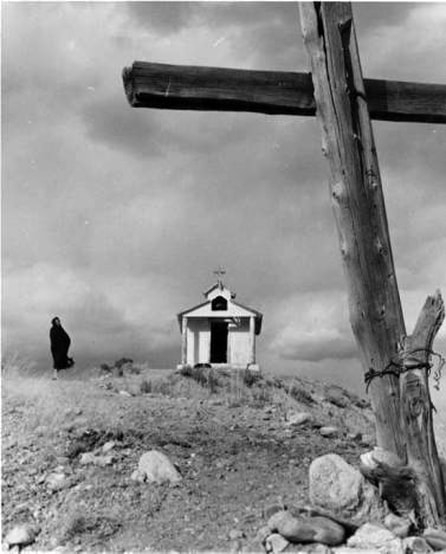

La Procesión de Sangre de Cristo With a review by Scott Duncan-FernandezThe next morning, Good Friday, found me in bed with a high fever. The chill that permeated my body had increased during the night, but anxious to join the Hermanos at the morada, I struggled to rise, only to fall back weakly against my pillow. My grandmother, who was drinking coffee with my mother in the kitchen, came to the doorway. Silhouetted in the rays of the sun in the window behind her, she seemed enveloped in a cloak of white. My fears of the night were dispelled, there was no bandage, no limp to her walk; and in the light of day I chided myself for my foolishness, convinced that my fever had caused such disturbing thoughts. That my abuela was here was no accident, no inexplicable coincidence to agitate my imaginings. For she knew that I had become a novicio the night before, and as médica, she had come to see how I fared. She moved to my side with a jar of her remedio, turned me to my side to rub the romerillo, or silver sage, on my back, and then tucked the quilts around me once again without a word. My mother placed a mug of warm broth in my hands, brushing a gentle hand over my cheek and pulling a chair by my bed for my gramma before she left for the church with my aunt. A few of the women would give the capilla a light cleaning before covering the saints with cloaks of black this morning to symbolize the dark day of Christ’s death. They would remain concealed until Easter morning, the day of His resurrection. Settling herself comfortably, gramma took from her apron pocket a small kerchief with a trailing thread and proceeded to continue her embroidery on its edge, the needle whipping in and out of the intricate design with a delicate, almost birdlike fluttering of her hands. I sipped the warm soup watching her, waiting for her to speak. I knew I had inherited my physical appearance from her, the small, thin stature, the nose, and her humor. Had I also inherited a mental power I didn’t understand, or want, from my beloved grandmother? Before I could ponder the question further, before I could think of a way to phrase my question without hurting the feelings of the tiny woman seated beside me, she spoke. “You have a gift.” Her words revived my concerns that the warm broth had begun to dispel. She looked up from her embroidery. Although this was one time I wished I could turn away, I forced myself to look into her eyes. Bright with tears, hers held a mixture of sadness and regret. When she blinked the drops away and smiled softly at me, there was also pleasure and expectation in their depths. “The gift of sight,” she began, “is strong in our family though inherited by some, not all, through the generations. And,” she added, “while some seemed only to possess a strong sense of intuition, there were others who had the power to know other’s thoughts, especially of people with whom they were close. “I will tell you a story, hijo, a cuento of a young girl you know well.” Putting her embroidery aside, she settled back into the pillow at her back and continued. “When this girl was very young, she began to have disturbing dreams, dreams which frightened her because in the days that followed, they would almost always come true. More and more often as she grew, the dreams plagued her. And her abuelito, the only one who believed her, died before he could explain the gift she had inherited from him. She learned to keep the dreams secret because whenever she told anyone, they looked at her as if she were loca. And people, ignorant and afraid, had started to think she was either crazy or a witch. Years passed, until one night she saw her father in her dream and knew what real fear was. In her vision her father was being dragged by horses in the field he was plowing, his leg entangled in the reins behind the arado.” She paused, taking her sack of punche from her pocket to roll a cigarette. I squirmed restlessly on the bed. From past experience, I knew that it was an effort in futility to urge her on, for if prodded to finish a cuento before she decided she wanted to, she was known to teach me a longer lesson in patience, sometimes making me wait for days, or until I had even forgotten the beginnings of a story and her teasing reminder would set me off, begging for the end. I had to hand it to my abuelita; she knew how to build up the suspense in her stories like no one else. I was forced to wait as she took a laboriously long time rolling her smoke, her eyes twinkling with mirth at my discomfort. “Where was I?” she asked, striking a wooden match on the sole of her shoe. “Oh, yes, the dream.” Puffing a small stream of smoke, she continued, “The next morning, much to her dismay, the girl’s father had already begun to plow the fields when she awoke. Without breakfast, the girl ran out of the house, straight to the field.” When she paused to puff her cigarette again, I could have screamed from the suspense; it was killing me. “Now, the neighbors had honey bees,” she reminisced, “and the hives were just across the river. For some reason, I never knew why, they swarmed—and the girl’s father with his horses were right in their path. It was a good thing the girl got there when she did, for her father, strong though he was, was already struggling to keep the horses from running away with the plow. When she looked down, the girl saw that the end of one of the reins had tangled around her father’s leg, just like in her dream. And just as the panicked horses took off, shaking the bees from their heads, she jumped forward, unwrapping the rein just in the nick of time to save her father from a very bad injury—perhaps even death.” Gramma puffed at her cigarette a moment before she added, “That was the day the girl finally realized that her dreams were not the curse she had thought they were all along, for years having been afraid that perhaps she was a witch and that she had dark powers from the devil. They were forewarnings, a gift from God, and she had learned to read their meaning to help others.” Putting her cigarette out, she looked at me closely, searching my eyes for understanding. “Sí,” she said quietly, “I have been called bruja many times, hijo, but only by the ignorant or the envious, God help them. They do not know that what I have is a gift from God and that I have learned to use my gift to avisar or to give consejo to those I see in my dreams.” I breathed a sigh of relief, knowing that no matter what happened in the future, I would never suspect my abuelita of being a witch again. And I understood that my father possessed a different gift, a power to read my thoughts and to respond in the voice of my conscience to guide me in the journey of life. But at the same time, I was troubled. Hadn’t I also inherited such a gift, a power to see or hear things others didn’t? I knew she picked up the apprehension in my eyes, for my gramma said softly, “No te preocupes. Do not be worried, hijo mío. Instead, thank the Lord that you have something not many people do and learn to use your gift to help yourself and to help others if you’re able. And if your friends question your intuition, you do what your conciencia tells you. If they are real amigos, they will look to you for consejo. Advise them well. If they are not, then you will have to live with their suspicions and their accusations just as I have. And though it will be hard, you will have to learn to leave them to their own consciences.” I nodded, and we sat in companionable silence for a while. My gramma took up her embroidery again as my mind digested the importance of her story, her counsel. I knew that I would have to find within myself the strength to overcome my disquiet, to listen and watch for any avisos in the future, to use my gift of intuition wisely. Suddenly remembering what I had seen the night before, I asked, “Do you believe there really are witches?” “¿Por qué?” she asked, looking at me quizzically. I described our encounter with the ball of fire and what Berto had done as it had fled. She nodded, “There are many, including myself, who have seen them. And since there is no explanation for the balls of fire, there are many who believe that they are witches. No one knows for sure. But it has been a long time that any have been seen around here.” “What do you believe?” I asked, a little uneasy about her answer. “I believe that there is a power of good, which is God. But the Bible tells us that there is also a power of evil. Just as Dios gives His children gifts which help them to live as good Cristianos, then so could el Diablo guide those he chooses with the powers of darkness.” She crossed herself before she looked at me for a moment. “That you saw one during la Cuaresma disturbs me. This is one of the most sacred seasons of the year. If it was a bruja or some other work of el Diablo, then they seem to have no fear that this is Lent, and today is Viernes Santo, the day our Savior died.” “What could it mean?” I whispered. The heavy silence of our thoughts spoke volumes, for we both knew that this afternoon La Procesión de Sangre de Cristo, the procession of the Blood of Christ, in which a chosen Hermano would carry the crucifix from the morada on his back, would be enacted. And even though the Penitente would not be crucified, the re-enactment of the most sorrowful day in the life of our Savior would take its toll on the Brother who played the crucial role. I wondered if it would be the Hermano who had portrayed Christ the night before in la Procesión de la Santa Cruz. Procesión de la Semana Santa. José on the left, carrying la bandera; Miguel's house in the background. Before either of us could speak, my mother rushed into the house, bringing with her a bit of news that brought an unwelcome confirmation and a bit of relief to our uneasy thoughts. A neighbor found the Lunática sprawled unconscious and bleeding from her head outside her house. He had summoned her hired hand to transport her to the doctor in Las Vegas. “What do you think happened to her?” my mother asked, looking from my grandmother to me and back at her again. My abuela’s face mirrored my thoughts: a bruja! Could the one who had protested the most loudly that she was surrounded by witches and lunatics in fact be a witch herself? Could Berto’s rock have met its mark on the floating ball of fire, leaving in its stead a wound in a witch that would cause her death? I knew that neither my abuela nor I wished the woman harm, yet I saw in her eyes the question I felt in my heart. If the woman died, then would the significance of the ball of fire we suspected be dispelled by her own death? Unable to rest and unable to sleep, I rose when Berto appeared at my door about noon, sent to see if I was well enough to go to the morada before the procession began. At first my mother protested, having heard of my induction from my father earlier that morning. But rising unsteadily, I assured her that I felt better and that if los Hermanos had sent for me, surely I was needed at the morada. Physically, it was the truth, for my chills had subsided and I was no longer dizzy, but my mind whirled with questions and an impending sense of doom. Concerned about how Berto would react if he heard of what had happened to the Lunática from someone else, I broke the news to him gently. Though I tried to convince him that we didn’t know whether the woman was only an innocent recluse who had fallen, perhaps even attacked by a thief (which was unheard of in our community), I heard the doubt in my own voice and saw the disbelief in his eyes. Berto remained convinced that the woman was a witch and that she had been injured by his hand, the hand which had cast the stone. He ran his fingers through his shock of hair again and again, upset about her probable revenge. I, too, worried for Filiberto, remembering my grandmother’s words. When we arrived at the morada, the Hermanos were resting beneath the shady cottonwoods outside. I went from one to the other exchanging greetings, touched by their concern. My father beckoned to me, moving a little away from the others so we could speak in private. He asked if I was up to the long hours ahead. After I assured him I felt fine, he told me what had been decided during the morning in my absence. When he told me who would be the Cristo in the procession of the afternoon, I frowned. My Tío Daniel who had been chosen for the honored role the night before had asked for and received permission to again portray Christ in the reenactment of His walk to Monte Calvario. I needed to tell my father about the premonition of impending death I sensed, but there was no way to explain without beginning with the ball of fire the boys and I had encountered the night before. So I took a deep breath, plunged in, watching his eyes widen when I told him what Abuela and I had discussed, and finished with the account of the neighbor woman’s mysterious injury. I breathlessly waited for his reaction. He took it all in, quiet with thought before he spoke. “I am glad that your abuela explained about what it is to be a gifted member of this familia,” he said, “for from now on you will listen more closely to your intuition to guide you on the right path in life.” “But that’s just it,” I blurted, “I have a queer feeling about what gramma said about someone dying. As much as I don’t like that lady for how she treated gramma, I don’t wish her dead, but if she does die, at least that might mean Tío Daniel won’t.” “Perhaps Mamá is right,” he said. “I trust her judgment,” he added, laying a hand on my shoulder, “as I also trust yours.” He stood, and I felt a surge of pride that he spoke to me as one man to another. I waited for him to say that the procession to follow would be canceled or that he would put it to a vote of all the Hermanos, but when he spoke I knew that it wasn’t something he had the power to do. The rites and rituals of the Penitente Brotherhood were clear, and the reenactment I dreaded would proceed as usual. “We will do what we must,” he said with determination, “and we will pray that Daniel will not be the one who has to die with Cristo tonight.” We walked together back into the morada where the rest of los Hermanos were in prayer. The window, covered with a dark cloth, let no welcome warmth or light into the room. In the chill of the thick adobe walls there were only the flickering flames of candles to shed a wavering glow on the altar and the men kneeling before it. As we joined them, I took the crucifix I had finished carving, painted black the day before, and placed it among those of my Brothers and the small covered santo Pedro had carved. Kneeling, I waited for the peace I always felt when I prayed there. I longed for the solace I would have received if I were able to look into the face of the Savior. But every retablo, every santo, was covered in shrouds of black. I felt a sense of loss, of foreboding—until I closed my eyes. From the dark recesses of my mind the face of Christ emerged, filling me with strength to face whatever might occur. It was a little before two o’clock when we emerged from the morada, blinking our eyes in the welcome light of the sun, warming our stiff bodies in its rays as we were surrounded by the friends and relatives who had come to join our procession. Women bustled into the cocina with pots of food while others entered the prayer room for a moment of contemplation before we began. I greeted my mother and grandmother with a hug, reluctant to let either of them go, for in their arms I felt the comforting reassurance of my youth. I found myself close to tears, realizing that the innocence of my childhood was lost to me, only to be remembered in their embrace with the bittersweet knowledge that I had willingly forsaken the child within me and let the man in me emerge when I took the vows of a novicio. Collecting myself as best I could with the tumultuous emotions and frightening premonition looming over my thoughts, I made my way over to the boys who were resting beneath the trees, knowing if anyone could take my mind off my worries, it would be the gang. Horacio was speaking as I joined them. “My gramma told me a cuento once,” he said quietly. “She thinks it’s only a legend though, ’cause she never really heard of it happening in her lifetime. Her own abuela told it to her when she was a girl. Do you wanna hear?” Berto nodded. “Anything, if it’ll stop me from thinking about the bruja.” We all looked at Berto sympathetically, wishing we could relieve him of the burden of his fears and knowing there was nothing we could do except keep his mind off them. Horacio began, “Well, you know how Tío Daniel is going to play the Cristo and carry the cross on his shoulders in a while?” “Don’t remind me,” I waved a hand at Horacio to continue when the boys’ confused looks turned on me. I was thinking of my uncle’s nightmares about the war and wondering if this was his penance for some unimaginable act. “Anyway,” Horacio continued after looking at me askance, “my gramma told me that one of the descansos up there,” he pointed his chin to the mountains beyond the church, “is supposed to be a real grave, the grave of an Hermano who died while he was acting the part of Christ.” We gasped. Pedro added, much to my discomfort, “It could be true, you know. I heard my papá and my grampo talking once, and they said that in the old days the one who played Cristo was really crucified on Viernes Santo, only instead of nails, they used ropes to tie him to the cross.” I was unable to shake off the chills that rose up my spine. Though I noticed the others squirming as well, I knew my distress for my uncle was greater than theirs because they had no knowledge of my conversation with my grandmother. “All I know is what gramma told me,” Horacio finished, leaning toward us. “She said that if it was true, then the Hermano who died would go straight to heaven. In those days, no one was allowed to witness the procession, but what was stranger was that the dead man’s shoes were left on his doorstep so that the family would know how he had died, and for a whole year no one but the Penitentes knew where they had buried him.” We all took this bit of news in silence. I pictured the scene Horacio described and thanked the Lord silently that we didn’t do things the old way anymore, and then Pedro spoke up as if reading my mind. “I’m glad we don’t do it that way anymore.” We all agreed. However, as we rose to join the men already getting into formation, I saw the black crucifix carried on the shoulders of two Hermanos who emerged from the morada. The moment for which I had longed for so many years—and only today had come to dread—arrived. For the first time, I would take part in the procession of Penitentes, but the pride I felt was overshadowed by the knowledge that my uncle, whom I loved like an older brother, would be in the lead carrying the heavy cross. I knew my eyes would be upon him all the way. Coupled with my foreboding that someone would be dead before morning, my first procession became a penitence indeed. I sighed heavily, lining up with Pedro at the rear of the group. As everyone who gathered to join the procesión took their places behind us, I was surprised to see Primo Victoriano, leaning heavily on his bordón, directly behind me with his wife, Prima Juanita. I noticed Berto and the others positioned behind him, ready in case he needed assistance. I turned and offered the elderly man my hand. “If you get tired, everyone will understand if you have to stop,” I told him in a whisper. “I will,” he promised. “I just had to come one last time, you understand?” The longing in his withered face was enough to tell me that this might be the last Lent he would see in his lifetime, that this might be the last chance he had to join his Brothers before age or ill health took its toll. I nodded in understanding, but I saw the weariness of his eyes, in the way he leaned on his cane, in the way his breath emerged from his mouth in short, tired gasps. “Don’t overtire yourself, primo,” I warned, but he only waved my concern away with a hand. The procession began when my father’s voice rose to announce that this was the reenactment of the Passion of Christ. My Tío Daniel, the massive black cross on his shoulders, moved forward, setting the pace for us to follow. “Oh—ohhh, imagen de Jesús doloroso para ejercitarse en el santo sacrificio de la misa como memoria que es de tan sacrosanta pasión,” my father intoned, telling us to imagine our dolorous Savior fulfilling His destiny in such a sacred sacrifice in our reenactment of the memory of such a sacrosanct passion. I read along as the rest of the Hermanos joined in, my voice blending with the varied pitches of the men, rising and falling with each line. The music emerged as if from our very souls to waver and float around us as we spoke to our Savior in a somber hymn rather than with mere words. The very tone of our combined voices and the reverence with which we sang spoke volumes as our words conveyed how much we believed in the passion of our Savior. My father’s words conveyed that Jesus had revealed many times to his faithful servants what was to follow. And though no one actually did the things to my uncle that my father told us, he paused with each recitation, and the weight of the words he spoke with such tremulous emotion made us feel that just by describing the terrible things done to Christ he felt them in his heart as he carried the symbolic cross. Then the first time he stopped, Tío Daniel spoke loud enough for all to hear the words that indeed seemed to be the words of our Savior: “Primeramente me levantaron del suelo por la cuerda y por los cabellos viente y tres veses.” My uncle revealed, “First they lifted me from the floor by rope and from my hair twentythree times.” As he resumed the pace for the procession to follow, my uncle paused twenty-one more times. His pace slowing with each pause, Daniel fought the trembling of his legs. I saw his shoulders bend under the cumbersome cross, symbolically weighing heavily in our hearts each time he staggered under its massive bulk. Even from where I stood, with twelve men before me, I heard his breath come more heavily, his voice emerged more tremulously, the words quaver as he described the countless terrors suffered by Christ in His passion. “They gave me six thousand, six hundred, sixty-six lashings of the whip when they tied me to the column …. I fell on the earth seven times … before I fell five times on the road to Mount Calvary …. I lost one thousand twentyfive drops of blood.” By the time we were halfway to the church, many of the women were sniffling, wiping their eyes with their kerchiefs. But the worst was yet to come as my uncle continued, weakened but undeterred in fulfilling his role. “They gave me twenty punches to my face …. I had nineteen mortal injuries … they hit me in the chest and the head twenty-eight times …. I had seventy-two major wounds over the rest.” By this time some of the women were weeping openly, and the smaller children, frightened beyond belief—I knew because I was at their age—began to sob quietly at their mothers’ distress. Primo Victoriano stumbled behind me, and I stepped back to grasp one elbow as Berto took the other. The determination in his face to reach the capilla, to finish the procesión as an Hermano one last time, was heart-wrenching. And as I took some of the weight off his feet with my support, I felt tears gather in my eyes. “I had a thousand pricks from the crown of thorns on my head because I fell, and they replaced the crown many times,” my uncle’s weakened voice continued. “I sighed one hundred nine times … they spat on me seventy-three times.” The tears flowed down my face. I heard Primo Victoriano’s labored breaths at my side. I thanked God the procession had come to an end, for the words were too painful to bear, humbling our Christian souls to the core of our being. “Those who followed me from the pueblo were two hundred thirty,” my uncle finished, “only three helped me …. I was thrown and dragged through barbs seventy-eight times.” As we reached the capilla, my uncle was barely moving, his feet shuffling wearily in the dirt, his breathing labored. When he leaned precariously forward, the cross threatening to smash him into the earth, several women cried out in alarm. Leaping quickly to his aid, my father and Primo Esteban each grabbed an end of the beam lying on his shoulders, relieving him of his burden just as his knees buckled beneath him and my uncle fell to the ground on hands and knees. When I saw him fall, his face grimaced in pain, my heart throbbed in fear that he could be gravely hurt, that my premonition of an impending death would come true. I would have rushed to his side but for Primo Victoriano, whose arm clutched mine tightly, his shoulder leaning heavily against me. If I left him, he too would fall. All the women were now sobbing as they looked at my uncle, trying in vain to stifle their uncontrollable cries because of the children, who, too young to understand what we did, cried with distress and sympathy for their mothers’ tears. A few of los Hermanos rushed to help my uncle to his feet, supporting him as they took him into the church. Though he was exhausted, my tío appeared to be unhurt, and a collective sigh of relief shivered over us. The women calmed themselves and mothers or older sisters hushed children’s cries into soft whimpers. Primo Victoriano continued to shake against me, his legs quaking with his effort to remain standing, his breathing heavy. Beginning to falter under his weight, Berto motioned for Pedro to help us, knowing that my scrawny frame wouldn’t be enough help to get the elderly man into the church. Relieving me quickly, they placed our primo’s arms over their shoulders, supporting his weight between them as they moved slowly into the capilla with his wife at their side. Following with Horacio and Tino, I heard Primo Victoriano mumble disappointedly at himself that he had no strength left to light the fire or the candles inside. Exchanging glances and nods, we hurried inside, so that when our Primo reached the door, I was busily feeding the flames of the kindling I had lit in the stove and Horacio and Tino were moving from candle to candle quickly. Turning as he entered, I smiled, glad that we were able to relieve him in his duty now that he needed us. Primo Victoriano only nodded, but the gratitude in his eyes said it all before he allowed the boys to settle him comfortably in the pew nearest the stove. When the Estaciones ended that evening, there was a silence unsurpassed by any service we had yet attended. I knew that for those who prayed with los Hermanos it was in part because of the anguish of witnessing la Procesión de Sangre de Cristo and the terrible sorrow of las Tinieblas that was to come back at the morada afterward. For Pedro and me, it was something more. We knelt with los Hermanos as novicios in the center aisle of the capilla as we made our slow and somber revolution of prayers and alabados around the retablos of the Stations of the Cross. I found my place in my faith, and it affected me as nothing before had done. It was awesome to contemplate. When my father signaled that it was time for our return to the morada, I retrieved my black crucifix from the altar. I blew out a candle with a fervent prayer for my uncle’s health and took another taper with me to the door of the now darkened church. Spotting Primo Victoriano, supported between his wife and Berto’s mother, I went to say good night. Someone had gone for a wagon to take the elderly man home, Prima Cleofes explained, for he felt tired. Prima Juanita clucked her tongue at her stubborn husband, but he didn’t need to say a word. The soft smile that lit his face told me that he had done what he had set out to do. He was content that he had accompanied his Brothers one last time, and he would toll the bell also for the last time that night before he would allow himself to be taken home. When I saw los Hermanos taking their places in the center of the road, I bade him good night, telling him to rest and not to worry, I would be there to help him on Easter Sunday as well. In the soft glow of the lanterns and candles, his eyes grew moist. Blinking back his tears, Primo Victoriano looked at me gravely. He said, “I will be here on Sunday, hermanito, and you will light the candles for me, but I will not see their light. I will not feel the warmth of the fire you will make.” Confused by his cryptic message, I searched his eyes. From the quiet contentment and resoluteness of his gaze, a silent tear that rolled down his withered cheek and touched my heart. My respect and admiration for the elderly Hermano who had fulfilled his desire engulfed me. On impulse, I hugged him close for the first, and for what would also be the last, time in my life.  Carmen Baca taught a variety of English and history courses, mostly at the high school and college levels in northern New Mexico where she lives, over the course of 36 years before retiring in 2014. She published her first novel in May 2017, El Hermano, a historical fiction based on her father’s induction into the Penitente society and rise to El Hermano Mayor. The book is available from online booksellers. She has also published eight short pieces in online literary magazines and women’s blogs. Capilla de Santa Rita, Penitente chapel near Chimayo, New Mexico Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA) Negative number: HP.2007.20.562 El Hermano: |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed