Giggles y Yoby Tommy Villalobos Giggles walked like she was dancing to Oldies But Goodies, Volume One. But she also looked sad all the time. It was like she wanted to be sad. Her friends already had a Sad Girl so they called her Giggles. People called me Gordo. I wasn’t fat. Maybe just a little. But let me get back to Giggles. She was the finest one in the Projects, 1950’s. One day, Lil’ Chango, skinny with a face that not even a madre could love, tried talking to her. He was barking like a seal up the wrong playa. I looked at her face when she was listening to the bato. Her lips were twisted. Like he was making funny noises with his nariz. He walked away with his head looking down, like he didn’t care if a carucha hit him. She looked at me and I made a serious face. Inside, I was laughing like when I saw that cartoon where the coyote gets hit by a giant rock when he’s chasing the pájaro loco. Giggles started walking again with that special wiggle. I wanted to tell her something like a priest. I walked fast. “Hija, you can tell me,” I said. She turned to look at me like I was a cucaracha walking around her sopa. “I don’t know you.” “I want you to.” “I like someone.” “Never saw you with someone. Never saw you with anyone.” She looked at me like I was another cucaracha but this time in her sopa. “Are you following me around?” “Even when I sleep.” I was trying to sound romantic like in a song. “Don’t!” “All girls like being looked at.” “Not me.” “We’re meant to be.” “Uh-uh.” She walked quickly away. Almost ran. People could ask me why I didn’t give up. You know, chase other girls who liked gordos. I would tell them that girls act in different modos. They can hate you but then you say or do something they really like, they grab you and put your arms around them. You feel like an octopus wearing a Pendleton. “Where have you been, Felipe?” said my mother as soon as I walked in the door. “Getting fresh air.” “There isn’t any.” I wanted to tell her about Giggles but she might not like her walk. “Áma, I like this girl and—” “She won’t be the last.” “This one is the first and only. She is special.” “She lives in Beverly Hills?” “Huh?” “Take out the garbage.” I took the garbage outside. A chavalo called Freddie saw me. “Hey, Phillip,” he yelled. He was the only one who called me by my name. “What?” I said to the mocoso. “You want to play baseball?” He didn’t see that I was grown up. Baseball was for chavalos. Girls were more fun now. “Freddie, I like girls now,” I said like I was confessing to a priest. “What?” Freddie was stunned, making a cara like I said I liked wearing dresses now. “One day, you’ll throw your baseball to your sister because you won’t be able not to.” I really thought of saying that because his sister Lydia was a better baseball player than him and she was only seven. “You’re talking crazy, Phillip. Go get your mitt, let’s play.” “Maybe later,” I said, knowing “later” really meant never. He turned and walked away. He turned back to look at me as if he wasn’t sure who I was. Then he disappeared into the Projects. I felt kind of sad. Like my childhood was disappearing with him. Then I thought again about Giggles and I wanted to kick Freddie and my childhood further into the Projects. God made something more fun than baseball. Then my friend since I forget how long, Jimmy, saw me. We were the same age. He was more serious than me. Of course, my mother would say everyone was more serious than me. Jimmy loved math and collecting baseball trading cards. His cards took up most of his life. And the girls all looked at him like he was Elvis. It didn’t seem to matter to him. He spent his time with his math books and cards. Everything else was for other guys. “Gordo, why are you standing there?” he said. “Thinking.” “About what?” “Not sure. Where are you going walking all fast?” “My mom needs butter.” “You still run mandadas?” “Sure. You don’t?” I nodded slowly. “Jimmy, oh, Jimmy!” said a high voice belonging to a running flaca with flying pelo. It was Lorna Ritas. She was in a race for Jimmy with Sally Lomenez, Linda Mistasosa and Maria Lobermie. They had a better chance with the real Elvis. Jimmy barely said “Hi” to them but each time they took it like he wanted to make out with them at Belvedere Park. Like that song, Jimmy only had eyes for Rachel Apenuz. Rachel Apenuz had no personality I could see. Jimmy saw something the rest of the world didn’t, like in those spooky movies. Compared to Rachel, Giggles was a shiny pair of spit-shined calcos. Rachel was like my sister’s paper dolls she used to play with. She was like cardboard. Her hair looked tired. In fact, she looked tired. But I was glad Jimmy didn’t see Giggles. Then I panicked, my mouth turned dry. Maybe he hadn’t seen her glide like a lowered carucha down Brooklyn and Mednik. “So, are any new girls waving at you?” I said, my mouth even drier now. He looked at me like I said something in Chinese real fast. “New girls?” “Yeah, like hot off the comal?” “What are you talking about?” “Is Rachel still your, you know…?” He nodded with a strange smile. “I still like Rachel.” I could breathe normal, again. Jimmy’s sister whistled for him from away off. She had the loudest whistle in the Projects. Jimmy ran off. I went back inside. I played “Earth Angel” by the Penguins on my sister’s record player. I played it over and over. The title said what I wanted to sing to Giggles. Then I fell asleep on my sister’s cama. The record player needle was stuck on the end of the record. “What are you doing?” my sister screamed, making me jump. My heart wanted to leave my chest and jump out the window to find somewhere better to live. “Man,” I screamed back, “you nearly gave me a heart attack.” “And I hate to fail. Now I’m really mad.” She got good grades in school. I think that’s why she said that. But she also had a big mouth my mother was always trying to slam shut. Hearing my sister’s big mouth, my mother came running like my sister was on fire. “¿Qué está pasando?” she screamed louder than even my sister. “I have to wash everything,” my sister said, looking around the room like I spread pulgas all over. “Don’t exaggerate,” my mother said. “He’s a pestoso,” she screamed in her chavala voice so all the Projects could hear. I think all the people in the Projects were smelling the air. My mother was quiet as if my sister said something like the president. “I was only playing a record,” I said, explaining things to the judge, my mother. Like a bailiff, my mother escorted me out of the room. My hermana had a crooked smile. The door slammed behind us. I would aim pedos into her room next time she wasn’t home. To feel better, I went back outside. In the Projects you always ran into someone who either made you laugh or was madder than you. Right now, it was Pete. He never made you laugh or mad. But he always had a problem to share. I tried telling him that was why he had a mother. That’s how they got gray hair. But today, I think I caught him at a moment when people feel like unloading a problem on the first person they catch. “Gordo,” he said, “I have a problem.” “You’re the last bato I would guess had one.” “What?” “What happened?” “I met the finest weesa ever made.” “Ever?” “Ever.” “Why?” “When you see her walk, it’s like seeing the ocean at Long Beach.” “Go write a poem.” I said. It sounded like he was talking about Giggles and I didn’t want to hear. “I have to win her heart first.” Pete wasn’t a bad looking guy like some of the truly ugly ones around, but right now he looked like the ugliest feo of all time. “I love Giggles,” he continued and I wanted to give him a Popeye-sized cachetada. “Who is ‘Giggles’?” I said with a shaky voice. I was a nervous liar. “She is a walking angel, like in the song, ‘Earth Angel’.” He said this with a stupid, faraway look. “You okay?” he then said. I felt mad then sick then mad again. “Sure.” “Are you sure-sure?” “Sure.” “My problem is that she is related to Jimmy and likes Loco.” I sat on the sidewalk. I saw Loco’s crooked right eye. I think he hated the world and everyone in it because of that eye. He was born that way. God wanted him to look loco so he took the hint and became one. “You look weird, man.” “Why Loco?” I croaked. “That’s what I want you to tell me. He is one ugly bato with an even uglier way with people.” “And she is Jimmy’s cousin?” He nodded weakly. “How do you know that?” “My sister.” “Oh, yeah. Your sister Rosie talks with everyone about everyone. The Queen of Maravilla Chisme.” “Hey, that’s my hermana.” “Everyone knows Rosie, Pete.” “Yeah, but you’re wise.” All those times talking to Pete, I was mostly trying to get rid of him. “So, what do you think?” he said. He wasn’t going nowhere till he got an answer. “Loco has that name for a reason. Jimmy is probably thinking of a way to stop his prima from getting hooked up with him.” I said that for myself. “What do you mean?” “He wants to stop him.” “Oh.” I always liked hearing Pete say “Oh.” It meant he was accepting what I said and would go away. Not today. “You know, Jimmy invited Loco to the show with Giggles?” I lost my words and thinking. Pete batted for me. “I saw them walking back to the Projects after they got off the Kern bus. Loco was laughing like a hyena.” My mother said life has surprises. One just kicked me in the head. “Should we jump him?” said Pete. “He would wrap you around me like a pretzel.” “So, what are you going to do?” he said. What I wanted to do was pluck Loco’s good eye out and do a pachuco hop on it. “It’s up to you.” “Then what should I do?” I felt like I was running his life when he should be running his own. “Find another one.” “Another what?” “Chavala.” “There ain’t no other around,” said Pete, looking around as if to prove it. “All good times don’t lead to Giggles.” At this point, I think I was again giving advice to myself. “Yes they do.” “What if she hates you? And your family? And your dog.” “She don’t know me. Or my family. And this is the Projects, we can’t have a dog.” “Maybe she has a drinking problem. She’ll start making ojitos at other batos.” “How do you know she has a drinking problem?” “Just looking at all angles.” “She could wet her bed, chew food with her boca wide open, have a voice like Jimmy Durante, and I would still like her.” “What if she has a record?” “Even if she was serving life at juvie, I would still visit her every day.” He was almost as crazy over her as I was. “Don’t you have a girl you liked? What about Edith?” “Edith was in the second grade. Her family moved out of the Projects when I was nine.” “Too bad.” “Huh?” He looked at me real let down. He walked away. I went and sat on my porch. I saw a girl coming toward me on the sidewalk. She was walking like a wave at Long Beach, like Pete said. It was Giggles. “Hello,” I said, trying to sound like some actor I heard in a movie. She kept walking like I had been a squawking perico. I was hoping for a “Hello” back or at least her head to turn up all conceited. But she kept walking. But then for a little bit, she turned her head toward me. Not mad or happy. Jimmy would make everything right. He would talk to his cousin and tell her that he and I were closer than gum under a zapato and she should grab me, crying. Jimmy said that they were cousins when he came to the door. “So, she just likes him like a cousin?” I said. “She and Loco are closer than gum in your hair,” said Jimmy. “So she likes him like a favorite cousin?” “She likes him like she likes to kiss him.” “That’s all?” “He kisses her back.” “You know Loco. You know what he’s like.” “Since we were babies.” I swallowed hard. Then I swallowed hard again. Then a third time and maybe a fourth. “You look like you swallowed a moco,” he said. “Why do you even know him?” “He’s my step brother.” Jimmy didn’t even say that like he was sorry. “Why?” “I don’t make the rules. Loco’s dad married my mom years ago. My mom had kids. He had one, Loco.” “So he can’t love Giggles?” I said. “Why can’t he?” “Because.” “She is my cousin but she is nothing to Loco. Well, that could change, but that doesn’t keep them from liking, maybe loving each other and making a whole bunch of kids to spread around Maravilla.” “That shouldn’t be allowed.” “What?” I walked away, stomping on the ground like it was Loco’s ugly ojo. I went to Pete’s house to report. He opened his door then smiled like if I was going to say that Giggles loved him. I broke the news over his head. But it was my own cabeza that hurt.  Tommy Villalobos was born in East L.A. and also raised there. He thinks of the lugar daily and love the memories while remembering the tragedies of his neighbors and of his madre. Tommy’s mother had a great sense of humor and he inherited about ten per cent of it. She had a quick wit and response to all verbal attacks, whether to herself personally or to her Catholic religion that she loved. Tommy dedicates all his works to her, knowing she had him when she had no idea how she was going to feed him and his four siblings. She was a single mom until the day she died. He lives in a boring suburb now, outside of Sacramento, but his heart and soul will always be in East Los Angeles where his mother was always by his side to protect him.

0 Comments

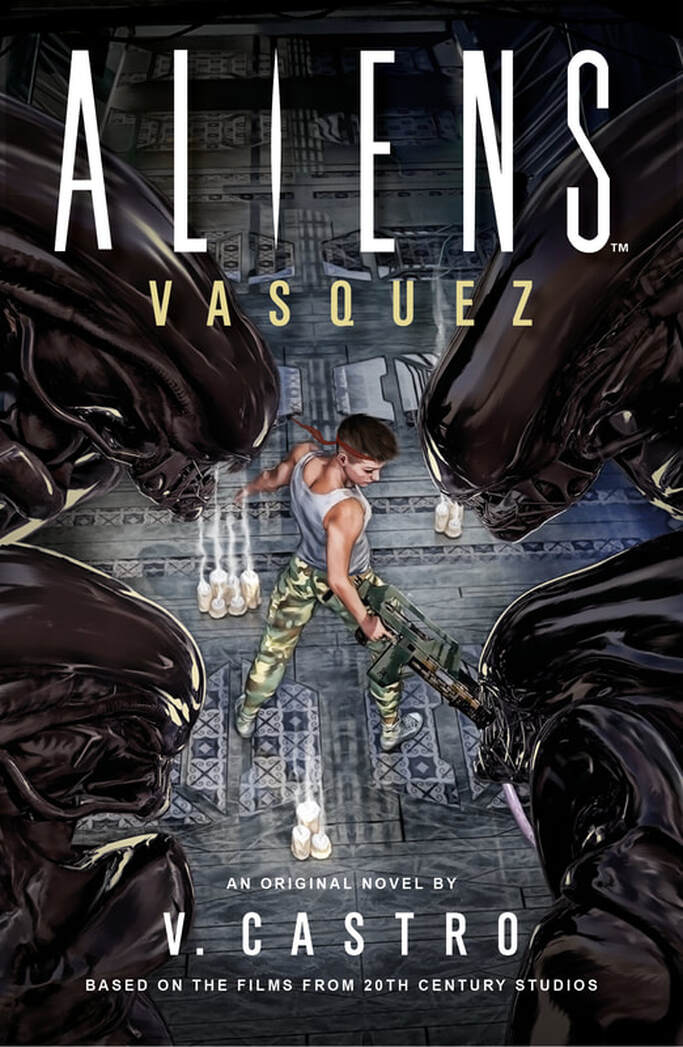

"Jenette was a warrior, had walked the warrior’s path, even if it was wayward at times where she stumbled with bad judgment. Now in this final test for the Marine Corps, she had to muster all the ganas of every soldier in her family who served before her. In this moment her bones weren’t made of calcium and marrow, but of steel. They would be steel for as long as she needed to get what she wanted." From Aliens: Vasquez Review of Aliens: Vasquezby Scott Duncan-Fernandez There’s more Aliens out there—the franchise has put out more video games, comics, and books—but it's the connected Predator franchise movie Prey that has people talking about Native women characters and representation in sci-fi lately. There's already been a famous bad ass brown woman in sci-fi—Jeanette Vasquez from the 80s movie Aliens. Some might point out the actress who played her wasn't a Chicana and the writer wasn't either. I recall some claiming she was a chola stereotype. My rewatch of Aliens as an adult showed the character was capable, brave, and dealt with typical racism despite her not being written or depicted by a Mexican American. Yet the character needed more. V. Castro in Aliens: Vasquez gives Jeanette Vasquez a Chicana soul and a past and goes beyond a plastic sheen of culture. The story pulled me in hard on the life Jeanette Vasquez and then her daughter Leticia living on Earth and as tough Chicana marines in space. Not only does the character from the movie Aliens get a real deal Chicana soul in this book, the Aliens franchise gets a Chicano outlook. The way Vasquez sees the world, how she lives, and how she fights xenomorphs is filtered by who she is. She is a brown woman who is connected to a chain of warrior women, particularly the Soldaderas from the Mexican Revolution, whose coiled hairstyle was famously borrowed by Princess Leia. The Aliens franchise has thematically been about women fighting patriarchy, dealing with the monstrousness of reproduction, sexuality, parenthood and inheritance of roles. As we all know Vasquez doesn't make it in Aliens, though tough to the end, and the book eventually hands her story off to her daughter, who also aspires to be an elite marine. Her corporate ladder climbing twin brother and she eventually meet up again on a mission involving the heads of the Weyland-Yutani corporation on a planet little is known about. The life of these two women, Jeanette and her daughter, is a struggle against the system, a patriarchy like many stories in Aliens, but compounded by poverty and racism. Chicano culture comes through as they honor Santa Muerte in xenomorph constructions and make ofrendas and a native weapon, a macuahuitl out of xenomorph bodies. The author V. Castro knows Aliens. There are allusions to other Aliens media throughout the book, some characters are ancestors, some places get mentioned. This is Jeanette and Leticia’s story, as much as Alien was Ripley’s story. Jeanette and her daughter have more against them, they are working class Chicanas, but they are tough, they inspire and finally represent in the way Chicanos want. Aliens: Vasquez isn't Aliens with taco sauce packets. It's a Chicana story that everyone can appreciate. This is more than representation, this novel is one of our stories, both in space and on Earth, in the future, something us brown sci-fi nerds always want. Of course, I want more and want to see sequels of Aliens: Vasquez and more from V. Castro. Aliens: Vasquez is available October 25, 2020 Scott Duncan-Fernandez a.k.a. Scott Russell Duncan’s fiction involves the mythic, the surreal, the abstract, in other words, the weird. He is Indigenous/Xicano/Anglo from California, Texas, and New Mexico and is senior editor at Somos en escrito Literary Magazine. In 2016 he won San Francisco Litquake’s Short Story Contest. His piece “Mexican American Psycho is in Your Dreams” won first place in the 2019 Solstice Literary Magazine Annual Literary Contest. His debut novel will be published with Flowersong Press in 2023.  V. Castro was born in San Antonio, Texas, to Mexican American parents. She’s been writing horror stories since she was a child, always fascinated by Mexican folklore and the urban legends of Texas. Castro now lives in the United Kingdom with her family, writing and traveling with her children. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed