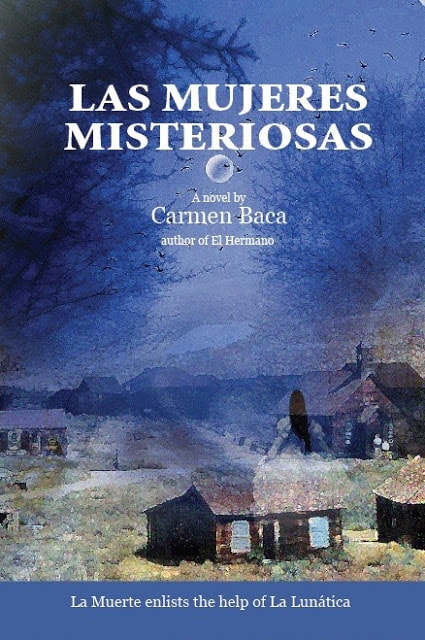

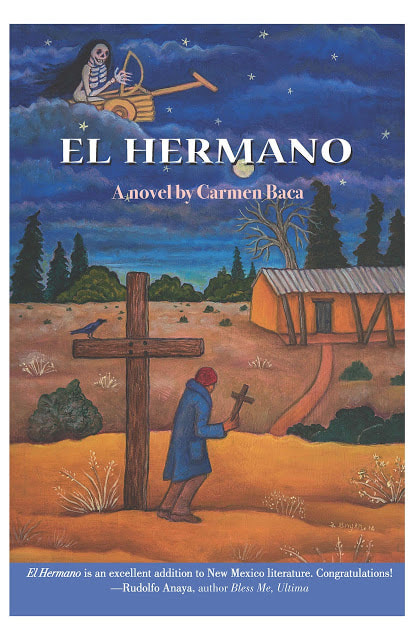

“Lechuza” by Carmen Baca I took my usual route home. Or started to, anyway. The blowout changed everything. My car slid on the snow-packed road until the bar ditch swallowed the right front tire. The car tilted and hit bottom. The motor died, taking the warmth from the heater with it. I turned the key, but the car was deader than dead. I reached for my phone, cursing myself when I remembered it was still on the charger at my folks’ house. I looked out at the slush turning to ice. I’d left before dusk, but the overcast skies made the sun vanish over the mountains quicker than usual. I had to walk or freeze. Maybe a car might come by, who knew? Granted, I was on a dirt road in a rural area, but people lived in small communities up ahead. I put my parka and gloves on, grabbed my flashlight, and exited through the passenger door since it was closest to the ground. I took a big breath and set off. I didn’t know how long it was before I noticed crunching behind me. I turned in a circle with the light sticking straight out. There was no one, not even the otherworldly glow of animal eyes. I listened for a bit and then kept going. Four-footed creatures didn’t concern me much; I’d had my share of encounters with deer, elk, even bobcats a couple of times. But I also watched true crime. Those are some of my favorite podcasts, too, so my traitorous brain turned to serial killer or rogue murderer. Meeting either one out here would end with me dead. The steps had stopped when I slowed anyway, so I kept walking—what choice did I have? The road was in the middle of a llano—a plain with few bushes and piñon trees not big enough to offer a hiding place. I walked faster, searching for something I could use as a weapon. The crunching started up again. The steps matched mine in speed but sounded uneven. My imagination took another unwelcome detour to the shuffling walk of Frankenstein’s monster. Houses up ahead gave me hope. Some were abandoned, but several had cars and trucks in front. The nearest one had lights on. I covered the next stretch of road at a jog, acutely aware the steps behind me quickened, too. When I got winded, I stopped and turned around fast, ready to face whoever followed. A pair of shiny eyes made me take a deep breath to yell. And then I exhaled in relief. It was an owl. It was still a ways behind me, but I could see the dark silhouette shuffling nearer. The shape was unmistakable. “Oh, hey, why didn’t you call out?” I laughed to stave off the hysteria which had been building up ready to explode. I took a few steps toward it. It stepped back. “I’m going over there, wanna come?” I pointed to the house just as whoever was inside turned out the lights. I could see the progression through windows from one room to the next as each went dark. “Oops, not that one.” I took off again, spotting another house with a light. The owl’s steps joined mine. I sped up. It was a bird, and I no longer felt real danger like I had for a panicked moment. But my thoughts started their winding journey through my mind again, and the apprehension remained. Why would an owl follow me? I remembered my grandmother, a Sioux, believed the owl was a messenger for evil creatures, though I forgot the name. It was a legend though, wasn’t it? Yeah, my dark mind supplied, but don’t some legends come from truth? Either way, an owl followed me on a deserted road, something I didn’t think was normal unless it wasn’t an owl. Really? You would think about that now. It’s just a curious bird, geez. I talked myself down from another panic and kept an eye on the road. That was when I noticed the light had gone out at the house I’d been walking to as if fate didn’t want me to reach help. “What the—,” I blurted. “They barely went to bed. They can’t fall asleep that fast.” I took those final steps to the entry. I banged on the wrought iron screen door, the reverberation making a racket I was sure the nearest neighbors, not just the resident, would hear. I rang the doorbell a few times, but no one came. I shouted a couple of times, too. Not a peep. “What now?” I couldn’t camp out on the threshold. I’d freeze by morning, and the homeowner would find me a corpse on his doorstep. If the owl turned into something else that attacked me, I’d damn well fight back. I knew enough to leave evidence like scratches on attackers. It would wear my bite marks, too, pájaro o no. I started off again, searching some more for something I could use to defend myself if I had to. My pal still traveled behind me, keeping the same distance. I wondered why it didn’t fly. I was more concerned about the question, is it just an owl? repeating in my head. I never did find a weapon, not even a stick. I hadn’t thought to look for a rake or something back at that house. I climbed a small rise, and on the other side was the village of Los Tecolotes, The Owls, since it boasted a healthy population of them. “Is that where you live?” I threw over my shoulder at my companion, keeping my eyes on the cluster of houses and hoping to see lights. Granted, more owls than people probably claimed this place as their home. I quickened my speed. I walked so fast I got shin splints and limped along for a while, just like in nightmares where I ran in slow motion from danger and snapped awake when I was about to get caught. That’s how it felt. My flashlight dimmed. I gave it a whack, and it brightened. “That’s all I need,” I muttered. The moonless night wasn’t as dark as it would be with no snow, but if I didn’t stay on the road, I knew I would jeopardize my already concerning situation. The light finally gave out after a while. “Whadda say?” I yelled to the owl. “Can we go to your place?” I turned to look back at the bird without stopping. The image of me cuddled with an owl somewhere was so absurd I burst into laughter. After a while, I snorted when I couldn’t catch my breath and made myself laugh harder. I don’t know when it turned to hysteria and sobs, but it did, and I stopped. Stood there with tears running down my cheeks until I yelled at myself again. Covered my freezing face with my gloved hands and made myself quit. I glanced at the tecolote, wondered what it must think of me—a madman who talked to himself. I shouted, “C’mon then. Keep moving.” I repeated the last phrase in a mantra with each step. After a while, I glanced up again. A house on my left made me blink. A light went on, propelling me forward. The bar ditch conspired against me again. I stepped right into it and fell face-first. The sharp pain in my left wrist from landing on my palms made me groan out loud. “Dammit.” Probably just a sprain, I didn’t know, but I cursed myself for not having looked first before taking that step. I got to my feet, cradling my wrist. The light went out. I took care as I approached. In the pitch black of the porch, I felt my way along the wall of the adobe house until I found the door. “Help!” I called, pounding on it. Surely, whoever shut off the light hadn’t gone to sleep that fast. I yelled loud enough to wake the dead. The thought made me laugh again, and as I slid with my back down the wall, once more my laughing became hysteria. The owl was gone. Before I could think about its absence, the click of the lock made me rise so fast I saw stars and wobbled like a drunk. The night’s vibes, the owl, and now—these weird clicks and menacing hisses coming from inside—gave off “get out of here fast” warnings. I took off again and ran until I couldn’t, and then I fast-walked and jogged and ran some more. Nothing followed that I could see. Other than my noisy footsteps and my heavy breathing, quiet ruled the frosty winter night. Numb with cold and spent, I would have probably found a place where I could hide and try my chances at surviving until morning if I hadn’t seen approaching headlights. The attack came from behind. A weight landed on my back and shoved me forward. I would’ve fallen but for something clamping my shoulders. When the pressure turned to pain, I reached up and back, my fingers sinking into something soft as sharp claws fought for better purchase. With a pop, what felt like blades penetrated my down-filled jacket, clothes, and my skin. I screamed then. My feet left the ground, and I rose about a yard. The headlights swept over the rise of the road at that moment. The driver must’ve slammed on the brakes because the car fishtailed and careened straight for me. I kicked my feet and punched at the creature’s torso and claws, right, left, right, left. It tightened its grip when my legs crashed onto the windshield and then let go. The car stopped when it hit a mound of snow, and I slid down the hood like a chunk of melting ice. I hit the road feet first and leaned over the car for balance. “Oh, hell! I hit you! Did you break anything? Are you hurt? Answer me, dammit!” I heard all this as my friend Tony got out of the car. “Behind you!” I pointed at a huge owl about seven feet tall—I could see it now—big and black in the taillights—as it took a step forward with wings outspread. Tony turned and bent over almost in one movement. Then he stood up, holding a chunk of snow-packed ice, and threw it at the beast. The direct hit to the head resounded with a crack before the owl screeched loud enough to hurt my ears. It advanced and then rose into the air, whooshing over our heads, and disappeared. Tony slid right past me on the icy road. I heard his “What the hell was thaaaat” as he passed. “Get back over here,” I yelled, watching him stop a few feet away. He returned in short, sliding steps. I stood, holding onto the hood with one hand and reaching out for him with the other. When he clutched my glove, I felt Tony’s tremors like they were my own. The night had gotten downright terrifying. “I hit it. Did you see? I got it.” “I did,” I replied. “But did you kill it or only wound it? And will it be back?” Tony looked at me with a face so filled with horror I got the chills. I had never felt such fear even when the bird had me in the air. My thought at that moment had been escape. My body had felt nothing but the pain and my response to danger: fight for my life. If we weren’t still filled with terror, we would’ve laughed at ourselves slipping and sliding, arms windmilling, short gasps and yells as we struggled to reach the car doors. I couldn’t dispel the feeling that every second we moved toward safety wouldn’t be fast enough. The owl would catch one of us this time for sure. But we got inside. I said a silent prayer of thanks when the engine turned over and heat blasted on high from the vents. “What the hell, Marty!” “I know, I know,” I said through chattering teeth. “Get us out of here.” “I’m trying, I’m trying.” Tony’s shaking made his foot fall from the clutch twice before he got the car moving. After a while, he found space to make a careful U, and we headed back to town. “Your mom called me around eleven. You never called her when you got home, and she was worried. She called your phone, and it rang in her kitchen. What happened? Where did you come across that thing? It was a lechuza, wasn’t it?” “I—I guess. Perfect timing, dude, thanks.” “What’re superheroes for? Mickey to the rescue.” He opened his coat and in the light of the dash, I saw his Mickey Mouse PJs. I chuckled despite the close call of a few minutes before. My shivers subsided as I told Tony about my night up until he found me. “If you hadn’t come by when you did…” I couldn’t finish with the mental pictures of my being eaten alive by the raptor. “Damn.” Tony shook his head. “At first, I didn’t see any bird. I just saw you rising into the air like you’d grown wings, and then you slammed into my car. When you yelled at me to watch it, I saw the lechuza. And then I just reacted.” “I’m glad you did, look,” I pulled at my jacket, showing him the rips in my shoulders. “Son of a—!” “Yeah,” I interrupted. “I woulda been a goner for sure.” Tony changed the subject, asking, “Where’s your car?” “I don’t know exactly. It’s halfway in a ditch. Can you take me to get it tomorrow? I want to find that house again, too.” When Tony gasped, I explained, “Aren’t you the least bit curious about what we’ll find there? As far as I know from the legend, the lechuza is a witch who turns into an owl. Maybe that was her following me all along, or maybe she was hiding inside. Somebody turned a light on to get me there. I wonder if I was supposed to be supper.” I shivered again. “I want to see her in human form. Meeting a real live lechuza—no one’s ever done that and lived.” Tony threw a look at me, a mix of disbelief and dread. “Did you just hear yourself? Either way, if she was your owl escort or if she was at the house, she’ll know who you are. She’s gonna want to get rid of witnesses. Hell, if she recognizes me, I’m a goner, too.” “But it’ll be two against one.” “Well, yeah—two against a monster bird with razors for talons and a carving knife for a beak.” Tony got me home safe and somewhat sound. When I opened my door, he reached over and plucked something from my hair. “A black feather,” he said, holding it between his fingers. “There’s more,” he nodded, pointing to my clothes. We made plans to go for my car around ten, hoping the sun might melt some of the ice by then. I silently thanked my old-fashioned landlord for leaving a phone line and called my mother. I retold my story, omitting the sensational details and assuring her I was fine. I tended to my wounds which were less serious than they felt, threw myself into bed, and fell into an exhausted sleep. In the morning after we pulled my car from the ditch and changed the tire, I made a mental note to equip my trunk with survival gear. Lesson learned. We got back on the road, and I kept an eye out for anything familiar to show me that spooky casa. I drove until a small adobe house came into my line of sight. Two state police, a coroner’s van, and the sheriff’s cruiser were parked helter-skelter in front. I slowed to a crawl, Tony right on my tail. It was definitely the house. A deputy waved at me to keep moving, so I did. Tony followed. “Was that it?” He asked from his car as he rolled by my apartment. “What d’you think that was about?” “Yeah. Nothing good,” I answered. Three days later we found out. The resident had been discovered frozen just outside her front door. Evidence pointed to foul play. Shoe prints in the snow, feathers strewn around the body, and a deep gouge in her head might’ve revealed the identity of the killer, but the person who discovered the body confessed he’d stepped into the mess to check on the woman’s condition. Too bad for law enforcement. They tried to shut down any gossip of her having been a lechuza, but the believers kept the conjecture alive. Equally bad was the feather incident in the laboratory when the evidence bag was unsealed. It was empty. Tony and I breathed easy when we heard. We agreed never to tell anyone the señora had indeed been a lechuza. No one would believe we killed a shapeshifter in self-defense, not when so few thought such anomalies exist at all. Instead, we’d be found guilty of her murder. After that night, I didn’t doubt others outright when they shared their incredible stories of strange sightings. Neither Tony nor I had believed lechuza was real until the night we faced her down. I didn’t like to think why she’d gone after me, I just figured she’d thought I’d been convenient prey. Good thing I wasn’t an easy victim, thanks to Tony’s timely rescue. We counted ourselves lucky to have escaped. The price for our silence we paid for with our internal and lifelong struggle with guilt. But we never jeopardized our freedom for a truth we could never prove. We made a vow the night we burned the feathers.  Carmen Baca taught high school and college English for thirty-six years before retiring in 2014. Her debut novel El Hermano, published in April 2017, was a 2018 finalist in the NM-AZ book awards program. Her third book, Cuentos del Cañón, received first place for short story fiction anthology in 2020 from the same program. To date, she has published five books and close to fifty short works in online literary magazines and anthologies. Her goal to make her mark on New Mexico literature comes from her desire to pass on elements of her Hispano culture which have disappeared almost entirely since she was a child. She believes we should embrace our culture, cherish our roots, and remember our elders to prevent losing important facets of our identities as Hispano people

0 Comments

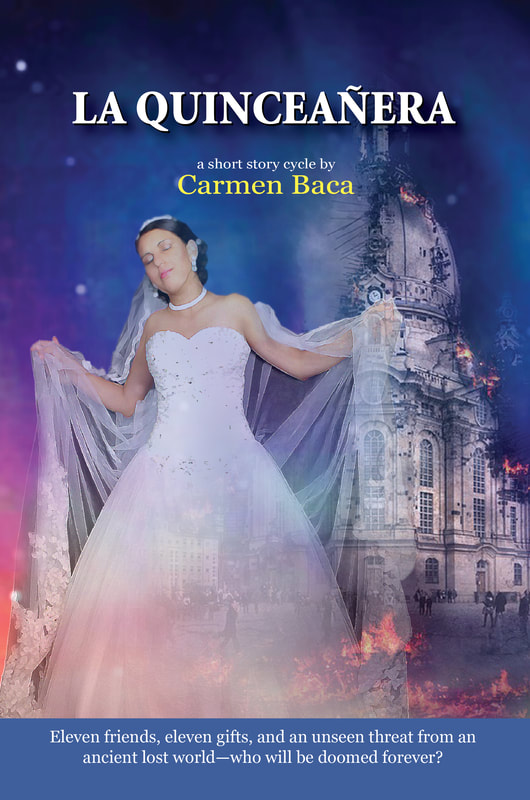

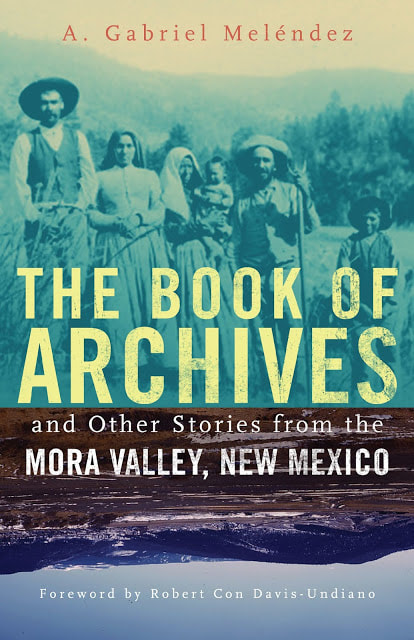

Cumbia Therapy is an intergenerational story told in three distinct sections, each exploring intimate relationships and la maldición put on four generations of women and meant to undo those relationships. Part I, Alzira, tells the story of Elena, a Mexican-American woman in her early twenties, and her Brazilian girlfriend, Alzira, as they meet in Italy, travel through Spain and Morocco and live for a time in Seattle in the mid-1990s. Part II, The Curse, explains the origins of la maldición, starting with Adela in revolutionary México and continuing in New Mexico. Part III, El Camino, explores how each generation of women questions the validity of the curse and deals with it in her own way. Cumbia Therapy has received an Illinois Art Council Fellowship. “Better a Bridesmaid” is an excerpt. “Better a bridesmaid” When Tío Freddy finally married Natalia, my sister Sofía and I had to be bridesmaids. We’d never been in a wedding and, as I had no interest in them generally and didn’t want to have one personally, I was not looking forward to all the hype. It didn’t help that Cristina, Natalia’s best friend and maid of honor, wasn’t thrilled about our inclusion and wanted to argue over every chingadita, including the scriptures Natalia had chosen for us to read at the cathedral. Cristina barked at me, “El pasaje tuyo is longer and more dramatic.” “Has leído El Anarchist Cookbook?” I asked. “If you want dramático, maybe slip in a paragraph or two from that.” She moved on to the dresses. “Este no me queda bien. These dresses aren’t suited for a mature figure.” Sofía said, “Ay, por favor. You’re just jealous because our figures are fifteen years younger.” Cristina stopped speaking to her and that meant she wouldn’t stop chatting me up. In truth, I hated the teal taffeta dresses and thought they suited Cristina much better. With the exception of a few hours on Sunday that included Mass, she wore miniskirts and midriffs everywhere and, after getting her chichis done, she liked showing off her cleavage—which the dress definitely did. By the second fitting I was tired of looking at dresses and hearing about Cristina’s date for the boda: a paleta man from Potosí. So, I decided to convince her to let me feel her chichis. The fitting area of Betty’s Bodas was crowded and stuffy and I whispered to her that we should step outside for some air. Then I slid around the corner, to the quieter side street, and as innocently as possible, said, “All this looking at women in dresses made me curious about your operation, Cristina. And I was wondering if I can touch them.” She stared at me a moment. “If you give me one good reason for wanting to, I’ll let you.” “I’ll give you two. First, I’ve never felt chichis other than my own. Second, I’ve never seen falsas.” “They’re not falsas,” she sniffed. “They just needed a little lift.” “Why not just get a good bra?” “You’ll understand someday.” I doubted it, but when she straightened her back and said, “Ándale,” I reached out and touched them. They felt like plastic baggies filled with Jell-o. Cristina lifted her shirt and bra and quickly showed me the scars. “¿Qué piensas?” she asked. “Pues...in my humble chichi opinion, the scars look painful, pero las chicas look nice and lifted.” The day of the gran ceremonia toda la familia met at mi abuelita’s to pick up boutonnieres and corsages. Mi Tía Gisela had a summer cold, but she didn’t let it stop her from walking around snapping fotos of everyone. Her fotos always came out blurry, off centered and with our heads chopped off, so no one bothered to pose. Abuelita was following Freddy around the house trying to convince him “to groom himself.” His reddish-brown hair fell to his shoulders in waves and he brushed it frequently and was careful about what he put in it. Women loved it, pero abuelita thought it made him look uncouth and insisted he tie it back, at least for Mass. “Do it for me, hijo,” she pleaded as he went from room to room, inspecting himself in every mirror. “Pero, mami, Natalia won’t recognize me.” “Then, por lo menos, shave your face. Natalia should see what you really look like.” “Oh, she’s seen me...” “No quiero saber, Freddy. Listen to me, please. You’ll thank me years from now.” We were just about out of time when abuelita and Freddy went into the blue baño and closed the door. When he emerged with his hair in a ponytail, without his mustache and forked-beard, we couldn’t believe it. Abuelita beamed and Freddy walked out of the house like a chamaquito forced to attend his big brother’s wedding. We got to the church and smashed into the back room where everyone congratulated each other on how lovely they looked. Cristina was wearing a pair of aqua-colored contacts that matched her dress. Abuelita took one look at those eyes and said, “¡Ay, Cristina, qué susto!” When the first few notes from the organ flooded the cathedral, I joked, “No turning back now,” and Natalia burst into tears. Sofía and I shared a we’ll laugh about this later look, then we grabbed our partners—Natalia’s cousins, shy as feral cats—and we headed up the aisle. After taking our places in the pews, we watched Natalia in her weeping moment of glory. When she got close enough to see Freddy’s face, she did a double take and Tía Gisela’s flash went off. As soon as everyone settled into the hard creaky benches, the priest began the old New Mexican tradition of roping the novios together with a large wooden rosary that resembled a lasso. I whispered to Sofía, “Ya vez, that’s what marriage is.” When the novios knelt, we saw someone had taken Kiwi’s white shoe polish to the bottom of Freddy’s shiny rental shoes. The left said Help and the right said Me. While the congregation attempted to stifle their laughter, Gisela started a stream of squeaky sneezes. Her gringo-date kept passing her tissues as if they were love notes, not snot catchers. The novios got to their feet and the sin vergüenza Cristina began motioning for Natalia to look at the bottom of Freddy’s shoes. Instead, Natalia snuck a peek at her own and, finding no chicle or puppy poop, shot Cristina a watchale! look. It didn’t take long for the ceremonia to lag. Prayers, preaching, promises to do this and not do that. I was ready for the fiesta. We’d already had a few, including an underwear party where we bought Natalia new chones, ate taquitos and played silly games for silly prizes. I knew that, in the hall adjacent to the church, kegs were being tapped, wine uncorked and champagne chilled. It was easy to imagine la cocina full of aromas and comadres arguing over who put too much salt in the frijoles and how picante the chile should be. The wedding finally concluded with a big beso where Freddy bent Natalia back like they were doing the quebradita. Then we marched into the hall that Natalia’s friends had decorated with blue-green streamers and purple paper flowers. Tío Freddy let down his hair and I traded my heels for Vans. The mariachis started with “Un rinconcito en el cielo.” They invited abuelita to sing a few songs with them and, after applauding louder than anyone, Sofía and I tried sneaking a beer to the bathroom. Tía Gisela, who should have been paying attention to her gringo-date, intercepted us. I said, “It’s for Carolina.” Our older cousin never drank, but Gisela just said, “In the baño?” “Yeah, she doesn’t want anyone to see her taking a swig.” I looked at Sofía and followed her eyes to Carolina, who was in a bright red dress talking to a group of people not far from us. “Hand it over,” Gisela said, holding out her germy hand. “¿Qué te importa?” I snipped. “¿A ti te importa if I tell your mamá?” We handed it over. After dinner the novios knelt again for La Entrega, which must have been uncomfortable con panza llena. It’s supposed to release the newlyweds to their new life and, though some people stage it at end of the night, my familia does it right before the dance, to release the novios to their fiesta. As the band tuned up, los compadres roped Freddy and Natalia together with a sandalwood rosary and gave them la long bendición while people tossed money onto Natalia’s long white train. Con el último amen Gisela tossed a dirty green bill that slid down Natalia’s silky back. As soon as the money was scooped up the band began to play. They waited about an hour for people to start feeling buzzed and generous before they started The Dollar Dance. I paid $4 to dance with Natalia and $3 to dance with Tío Freddy. He told me he liked my Vans, then he picked me up and spun me around. Sofía said it was dumb for me to dance with Natalia and I said what was dumb was her pinche statement. Natalia looked so stunning with her heavily outlined eyes and her blue-black hair pinned up that some men paid twice to dance with her, making The Dollar Dance nearly as long as the wedding. Freddy’s best man pinned dollars on my tío’s tux, but everyone in Natalia’s line pinned the bills on her themselves. When her train was covered men began carefully pinning money on the front of her dress. It made Natalia’s mother nerviosísima and she told the band, “Wrap it up, chicos!” She probably cost the novios fifty bucks. After all the bills were unpinned, one by one, Natalia danced with Freddy a couple of times before Gisela singlehandedly “stole the bride.” To no one in particular, her gringo-date said, “Is that a Mexican tradition?” I was standing next to him and answered, “No, it’s more of a Southwestern scheme to get more loot. One that happens to imitate the kidnappings latinos have become infamous for.” He stared at me and excused himself to get a drink. Gisela led Natalia to a coatroom at the back of the hall where she would voluntarily stay sequestered. Knowing everyone would just be removing more money from purses, pockets and wallets, when Cristina followed, I went too. It didn’t take long for Gisela to pop open a $200 bottle of champagne intended for the newlyweds’ private party and, while flattering Natalia and filling her glass, she snapped fotos. In between songs we could hear the bandleader: “Oye, the bride is still missing! Come and make a contribution to Comadre Yolanda so we can raise enough ransom to bring Natalia back!” The coatroom hosted more fotos, more drinks and, at last, the band announced, “Ya está. Tenemos el dinero suficiente and the novios are $453 richer!” By the time Yolanda tiptoed into the room in impossibly high heels, Natalia couldn’t have subtracted five from ten and she just hiccupped uncontrollably when Yolanda handed her a wad of cash. She passed it Cristina, who started counting. “What’d you do to her, Gisela?” Yolanda asked, nodding at Natalia. “¿Yo?’ Gisela sniffled, ‘pues, nada...” They argued, Natalia hiccuped and Cristina, who’d counted the money twice, asked, “What’d you do, Yolanda? Slip a fiver in your bolsa?” “How dare you!” Yolanda glared at Cristina as if she were a cucaracha. “We all heard the band say the crowd raised $453.” “You don’t know what you’re talking about,” Yolanda scoffed. “I needed to make change.” A new argument ensued that Natalia interrupted with her silence. Everyone stared at her. “Hiccups are gone,” she giggled. Cristina and Yolanda shuffled her back to the dance and the band said, “Let’s welcome the bride back! Let’s hear it for Natalia.” The crowd cheered. But Natalia’s mamá took one look at her daughter and cried, “¡Válgame dios! Natalia missed half the dance and, look at her, she’s as clumsy as a cow!” Natalia probably should have sat down and had some water, pero she fell into Freddy’s arms, in the middle of a Cumbia, and away she went. He had no idea his wife’s head was spinning like a top when, holding her hand above her head, he spun her halfway around so they both faced the same direction. He held her tightly for a few pulses, her back against his chest and his hand on her stomach. Then he gave her a media vuelta so she faced him again. Finally, he twirled her three hundred and sixty degrees with the left hand, a quick one eighty with the right, another with the left and, with two hundred eyes upon her, Natalia puked like a cat. I turned to Cristina and said, “¿Sabes qué? Forget the dinero—better to be a bridesmaid.”  Marcy Rae Henry es una latina chingona de Los Borderlands. She’s lived in India, Nepal and Andalucía and now walks her rescue dog by the Chicago River. Her writing has been longlisted, shortlisted, honorably mentioned and nominated for the Pushcart Prize and appears or is forthcoming in The Columbia Review, PANK, Epiphany, carte blanche, The Southern Review and The Brooklyn Review, among others. She has received a Chicago Community Arts Assistance Grant and an Illinois Arts Council Fellowship. DoubleCross Press will publish a chapbook of her recent poems. Excerpt from La Quinceañera, latest book from Carmen BacaLa Corona |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed