Una Cuadra Al Lago Del SilencioBy Tania Romero

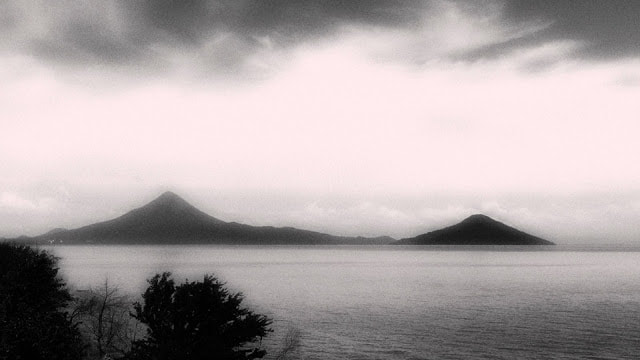

Every week, my memory turns to a place called Silencio. I first visited the place growing up in Managua, the same day my stepdad was late picking me up from preschool. I waited on the curb, watching snobby older kids with their chauffeurs; silver lunchboxes swung blissfully into air-conditioned Mercedes-Benz. The delicate, blue-eyed blonde girl with an unpronounceable name held her Chacha’s hand as she climbed the backseat. Nicknamed Vaquita despite her thin frame, she always brought an imported can of condensed milk for lunch; the kind only certain families could buy with a military carnet at La Diplotienda. I sat on top of a rock near the gated entrance, sipping the remnants of orange juice in my yellow plastic thermos. My mother squeezed fresh oranges every morning, because my family could not afford a live-in Chacha like the other kids. The liquid was still refreshingly cold on that sweltering midday. By the time I finished, everyone but the faded hero cartoon sticker on top of my lunchbox and I, was gone. Cars zoomed by and I longed to hear the engine roar inside the rattling red hood of my stepdad’s Lada. But it never arrived. In the adventurous spirit of characters like Red Riding Hood from the folktales teachers read before naptime at school, I decided to walk in the direction of Abue’s house all the way across town. Teachers always raved about the heroism of Caperucita Roja when she defeated the Big Bad Wolf with her wit; she was an intrepid pata de perro who didn’t sit nor stay. By car, Abue’s house was probably thirty minutes away from school. By bus, if one could find an empty seat among the mercaderas with heavy straw baskets heading to El Huembes (the local city market), it was a comfortable hour and a half. But measured in the steps of a five-year-old girl? Abue’s house was a sweat-drenching eternity in the scorching midday heat. As I walked down the unpaved side of the highway, the draft from the speeding cars occasionally lifted my pleated blue skirt, and nearly ripped the insignia from the left pocket of my buttoned-down white shirt. Dressed in blue-white, I probably looked like a miniature Nicaraguan flag in a windstorm. At a busy light intersection, I sat down under the shade of a mango tree. The skinny branches with long leaves ran for miles into the sky. Suddenly a blue-black Toyota pickup truck screeched to a halt before me. As the cloud of dust settled, I could discern it was La Guardia in disguise: The Big Bad Wolf from the cautionary tales Tío Miguel told me. When he was a child, La Guardia raided people’s homes like in the Three Little Pigs, huffing and puffing bullets into concrete walls to check which houses crumbled. They didn’t look for chimneys to climb because Managuan homes at the time, no matter the material, didn’t even have doors. Abue would force Tío Miguel to wear a dress before hiding him under the bed so La Guardia wouldn’t take him to a place called Guerra. It seemed no one in my family wanted to go to that place, and I was no different. Driving around the city disguised as a new wolf breed, La Guardia had a new namesake: La Contra. A Morena with curly black hair tied in a bun, dressed in an olive-green uniform and military boots, stepped out of the front passenger side. Sunglasses, the man at the wheel, wore a similar uniform except for a camouflage cap shading his face. For a slight second, Morena resembled my aunt Ligia who also had a flawless blend of Miskito cinnamon skin. She had the kind of skin shade that chelas like me wanted to have, even after enduring chancletasos from our mothers for standing in the sun too long. “Mirá vos,” she called for Sunglasses. “¿Dónde vas, chavalita?” she turned to me. I didn’t answer. “¿A dónde vas, Amor?” she reached out for my hand. When I touched her frosty skin from riding in the air-conditioned cabin, my whole body went numb. I had never been in the presence of a cadaver, but I imagined she felt like one. Del susto, sentí un soplo en el corazón. “Donde mi Abue,” I murmured. “¿Y dónde queda eso?” “Por El Huembes,” I replied. There was no turning back. She knew where I was going. My trembling legs synchronized to the offbeat patterns of my emergent heart murmur. Surprisingly, I felt like a grownup in that moment, referring to landmarks like a real city slicker. No one in Managua actually uses a number address; our postal codes are defined by the most accurate subjective orientation to places and things. We navigate the city by referring to markets, old buildings, monuments, lakes, or trees: “del Arbolito, una cuadra al lago,” we say. Abue had the habit of asking if a place existed before or after the earthquake, just in case. Morena opened the door and boosted me up to the backseat, placing my faded lunchbox next to me. As I scooted to the center, my overheated legs squealed as they rubbed against the plastic seats. The door closed behind me and Morena got back inside the passenger side; one last gust of hot air filled the truck, and I knew I had found Silencio. The air difference inside the cabin was palpable; the dead-cold breeze from the vents sent chills to the back of my neck. My mind went blank. I once heard that all girls should cross their legs when they enter Silencio, specially when La Contra is in the front seat. But that cold breeze would occasionally lift my skirt and feel satisfying as it dried my sweaty thighs. Every now and then Sunglasses would turn his head toward the front mirror. I could tell he wanted to be like the cold air penetrating my pores. Morena gave him some side-eye, but never said a thing. I kept pointing in the direction of Abue’s house, but Sunglasses drove slower. Slower, until time stopped. I wish I could recall more details about Silencio. But every time my memory roams in that direction, all I can remember is the smell. From a certain smell, una cuadra al lago de la memoria; that is the postal code of Silencio. Sometimes when I return, there is an overwhelming scent of burning plastic, mixed with the coolant from the air vents at full blast. Sometimes there is a pervasive smell of sweat and male cologne infused in the upholstery. At times the smell is a combination of gasoline fumes and burning tires. What I do know is that there is always a smell in Silencio. The next thing I knew, we turned left at the red-black prism memorial for the militant-poet Leonel Rugama, who never came back from Guerra. As we headed down the street, I could see the outside of my Abue’s house in the distance. The pickup truck pulled up to the front. Abue, in her embroidered green bata, dropped her transistor radio and jolted from her mesedora on the porch. Morena got out first and opened the door for me. I jumped out and ran as fast as I could out of Silencio. Abue’s eyes widened when she scooped me into her arms. Instinctively, she lifted my skirt to check between my thighs. Heart racing, eyes sealed, I squeezed tightly; my legs were shamefully frozen-dry but I was unharmed. Morena chuckled at how firmly I latched on to my Abue’s body. She gave Abue a warm nod and handed her my lunchbox. She returned to the front seat and rolled down her window. I watched her pull out a concealed red scarf under the neckline of her olive-green uniform, an identifying marker of bold volunteers who went to Guerra. She was not La Contra at all; she was a Cachorra. A Caperucita Rojawho prevented Sunglasses from turning into the cold air between my thighs with her silent wit. I never saw either of them again ever though they knew how to get to Abue’s. I figured like many others, they got lost coming back from Guerra. Thirty years later, during my weekly talk-therapy sessions, I try to deconstruct why I return to Silencio. Why I sit on rocks for hours. Why orange juice tastes better when served in a thermos. Why I sit under trees to purposely obstruct my view of the sky. Why I gravitate toward any body of water to find my place in the world. Why my nickname is pata de perro. And why I nod in silent gratitude at women who wear red scarves.  Tania Romero, born and raised in Nicaragua, moved to the United States with her parents at the age of nine, but never lost touch with her cultural roots. A poet, filmmaker, and media instructor, Tania is working toward her MFA in Creative Writing from UT-El Paso. Her award-winning short documentary film, “Hasta con las Uñas,” featured interviews with Nicaraguan women filmmakers, a poem of hers was recently published inSin Fronteras journal, and her photography will be featured in an anthology of Latina writers titled, Latina Outsiders. This short story is her first published short fiction.

0 Comments

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed