|

Review of ChupaCabra Meets Billy the Kid,

a Rudolfo Anaya Extra-Fiction Novel By Armando Rendón In Rudolfo Anaya’s latest book,ChupaCabra Meets Billy the Kid, science as in science-fiction gives way to the true fundamental forces of nature as he weaves a story that flashes back and forth in time. The title is misleading because it’s not really ChupaCabra, the goatsucker demon of Mexican lore, that meets Billy the Kid, a historical human artifact mythologized by Western writers of the purple prose, but a clash of realities. Obviously, the title suggests some weirdness going on. Is it fantasy, sci-fi, horror, a retro version of the time travel gimmick? Or is Rudy just pulling our collective leg? As with really good time-travel yarns, underlying the storyline are critical views of society, its social mores or disregard for humane values. I would say that in all the best science fiction I’ve read over half a century – that’s a lot of reading – writers generally conjure up the bad guys or create a social setting that contrasts with the narrator/author’s own time. In H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, the protagonist reconfigures a chair with odd bells and whistles, powered by who knows what and travels thousands then tens of thousands of years into the future. It seems he never returned from his last trip, so the Traveler may still be out there. In a way, Anaya has come, I was going to say, full circle, but only half circle back to his highly acclaimed book, Bless Me, Ultima, which is on many reading lists of schools throughout the U.S. Ultima, the curandera who becomes a spiritual guide for Antonio, the young protagonist in the story, imbues the book with her other-worldly persona and a powerful aura of mysticism. To Anaya, his homeland is a mystical place, the mountains guardians of secrets and beauties found nowhere else, its rivers arteries of life in an otherwise harsh land, and a challenge to survival which his forebears have continually encountered for generations. I’ve caught a glimpse of these truths—seeing how mountain peaks jut up to cut off the horizon, finding a río at the bottom of a gorge by a glint of sun, leaning back a chair against a sun-warmed adobe wall... Anaya’s treatment here conveys the hardships of survival in the New Mexico of the latter 1800s into the early 1900s following the takeover by the U.S. government of half the territory of Mexico as a result of America’s invasion of Mexican territory beyond the Rio Bravo (Grande). Those hostilities ended with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848. Yet, this book also celebrates the nuevomexicanos who survived for generations from the meager resources the earth grudgingly gave up. Their devotion to a religion which was increasingly remote resulted in the creation of homegrown zealots, los penitentes, a secretive society of men who preserved the religiosity of the communities through extreme exercises of penitence and sacrifice. The hard life of the early residents resulted in a resolute people, determined to survive in spite of the hardships faced every day. This is how I perceive nuevomexico, from readings (Anaya’s works and others) and conversations and the few times I’ve ventured into the state, traveling far up toward the headwaters of the Rio Grande in the San Juan mountains of Colorado. Out of this history evolved a few persons whom I got to know personally: Tomás Atencio, who created a literary headwaters in Dixon, co-founder of La Academia de la Nueva Raza and author of Resolana: A Chicano Pathway to Knowledge; Enriqueta Vasquez, who was one of the first Chicanas to publish a book on the Chicano Movement (Viva la Raza, 1974) and was part of founding the newspaper, El Grito del Norte, in 1968, about the same time that Quinto Sol Publications arose in Berkeley, which by the way was first to publish Bless Me, Ultima, and Con Safos out of East Los Angeles; Esteván Arellano, a writer and photographer, who drove me up into the mountains the time I met Atencio, and Reies Tijerina, who was a Tejano, but allied himself with and became the most prominent leader of the land grant movement in New Mexico. And Anaya. This sampling of people and experiences inform my reading of ChupaCaba Meets Billy the Kid. I say Anaya circled halfway back to Ultima, because the plot in this book depends heavily on tried and true sci-fi gimmicks, though the story is set in the middle of the Lincoln County War of 1878. A super deep state government unit, operating out of the infamous Area 51, called the C-Force, which also answers directly to the White House; an incredible experiment run by C-Force gone awry which combines the DNA of chupacabra and alien DNA (think Area 51) to produce a devilishly vicious though sometimes clownish hybrid called a Saytir; the good-old wormhole angle worms its way in somehow (well, I know but I’m not telling), and the time-lapping magical laptop (magical because it seems to have a solar powered charger in 1878) that functions for note taking and for checking emails from this now (2018). The reference to the White House, that is, to an actual living person is rare in science-fiction. But Anaya’s story is happening in real time—his book is fresh off the presses. The president has authority over the C-Force and its members are continually advising him. (Does the C stand for ChupaCabra or Chili? Is C-Force to blame for the direction of current events? Is the current president really a Saytir?) In other words, Anaya throws every quirky sci-fi accoutrement ever devised into the fray. You’ve got to love it. Something seemed to be lacking in the story for me as I started to read it, but then I met the aspiring writer protagonist, Rosa, who believes it is her mission to write the true story about Billy the Kid. The true story, “it’s what every writer wants,” she says, still queasy though from some of the not so savory action she’d seen so far. So, lots of background fact-gathering, laying the groundwork for the story, but little of the spiritual or otherworldly that could connect us to his earlier writings, especially Ultima. Yet, Ultima lies in wait in the background throughout the book. For example, look for the flashback to the movie of the Anaya classic. Rosa, the young person documenting all these events and characters, teams up with Billy the Kid, who mysteriously shows up at her new-found digs in 1878 New Mexico. A sort of platonic relationship ensues—Billy is a very approachable fellow with the young ladies even though rather reproachable otherwise. So how does Rosa end up in 1878? Rosa’s chief means of transportation is by horse, of course. She witnesses key events in Billy the Kid’s last few days and shares the lives of kind Mexican American hosts who give her food and shelter, even lend her a proper dress for a señorita to go to el baile, basically because she is friend of Bilito, the Kid. Armed with her laptop and with a lot of time on her hands, so to speak, as she battles writer’s block or rides shutgun next to the Kid, Anaya, I mean, Rosa, ponders a number of issues: the very notion of time, the role of literature in culture, what is driving her even to consider writing about this outlaw and what happened in a backwater of history 140 years ago, like who cares? Rosa suggests that there is far more to comprehend beyond what we see or seek to comprehend. “Time makes something new of us all,” Rosa tells Billy as the Kid’s own timeline draws to a close. Some of us have more time than others, she fails to add. Rosa, of course, knows Billy’s last day is approaching—but she can’t reveal that fact. After what seems like months living in this past world, Rosa begins to worry about how she is to return; there’s no ponderous circus balloon she can take to get back home. Exactly the point, because we want to find out what happened, she has to come back to our real “time” and tell us, but how does she get back? A low-rider spaceship with hydraulics powered by frijoles de la olla? No, chale! The force that bends space and time, Anaya tells us, is beyond quantum physics, string theory, time warps, marvelous spaceships powered by dilithium crystals to visit San Francisco Bay in the 1950s, let alone a barrio kid’s scooter that magically carries him back to historic moments in Chicano history. We know that somehow she made it back. All the while she has been recording what she sees and hears. At the end of the book, she has graciously provided a detailed timeline, “Rosa’s Notes and Observations,” downloaded from her laptop no doubt of what she saw, so that’s proof. But the question still remains, how? When we find out what that inexorable source of energy is, all falls into place. This is what Anaya is getting at. It’s what he has been writing about all his life. How we ourselves can be transported back in time, back to a transcendent period of our own. It’s so obvious when you read the book. Armando Rendón is editor/founder of Somos en escrito Magazine, author of Chicano Manifesto (1971, 1996), and creator of Young Adult novels, including the four-part series, The Adventures of Noldo and his Magical Scooter, (2013-2016) and the latest Noldo novel, The Wizard of the Blue Hole (2018). For an excerpt from ChupaCabra Meets Billy the Kid, a Rudolfo Anaya novel, the book was featured recently in Somos en escrito under the title, “I am becoming a recorder of history.” The book is available at ChupacabrabyAnaya.

0 Comments

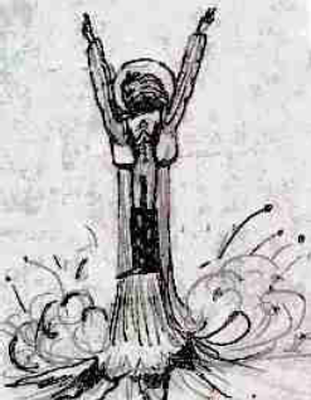

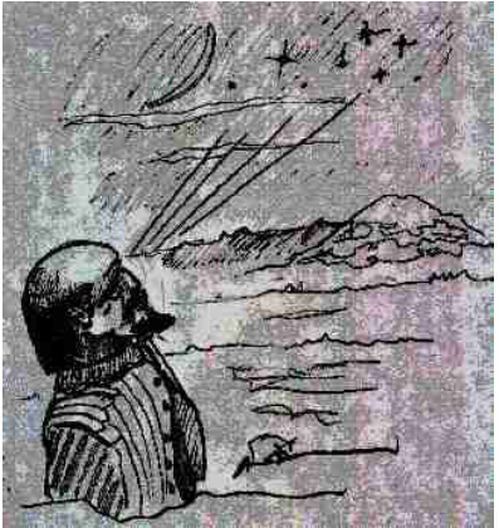

The Oñate Expedition’s Mysterious Encounter with a “Demon”, as Recorded by Capitán Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá in 1610 By Louis F. Serna, with sketches by the author When Cortez first saw the Aztecs and their magnificent city in 1519, he must have marveled at the sight before him! Coming from the then “civilized” country of Spain which was celebrating high prominence among their European neighbors, the Spanish were very conscious of the “style of the nobility”, high fashion, and the literary arts. They saw themselves as far more advanced and civilized than the people they encountered elsewhere, including the Aztecs. They and their European neighbors such as England and France considered themselves highly educated, and entrusted with the self-imposed righteous responsibility of bringing religion to heathens at every known port. With “soul saving” in mind, Spanish sailings included an abundance of Franciscan friars anxious to spread the word of God as emissaries of the Catholic faith and the Pope in Rome. Spanish monks saw themselves as duty bound to teach Christianity to those under-privileged savages they heard of from exploring conquistadores, and they couldn’t wait to have their names immortalized as “crusaders” and even martyrs. Certainly, those Friars would have known of all Spanish explorations of the time and of the many amazing discoveries as the Spanish sailed from port to port, seeing and reporting new places and people still in their primal evolution. As for Cortez, he must have been in awe of those Aztecs, their culture, amazing cities, their gold, and their advanced knowledge of astronomy. And certainly, he would have known all along that he was duty bound to take every ounce of gold they might possess, to enrich his King, Country, and himself. In the process, he almost certainly also knew that he would probably have to kill them all to get it! Thus began the Spanish “entrada” (entrance) into this new land called “Mexica”, “la nueva viscaya”, “la Nueva Espana”, “la Nueva Galicia”, and later to the north, “el Nuevo Mexico” (today New Mexico). Following the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs by Cortez, other notable Spaniards would quickly occupy the lands in the interior of what became Mexico and become rich off of its resources. Spaniards like Cristobal de Oñate, who established himself in the area of Zacatecas, rich in silver ore. He became a very rich man, taking tons of silver from “la Bufa”, that famous mountain some believed was made entirely of silver, and other mines punched into the countryside. By then, in 1540, another adventurous Spaniard by the name of Coronado was already advancing into the area to the north… the area where those Aztecs were said to have come from originally…. The lands where people lived in multi-storied structures made of mud brick and stone… lands that Cabeza de Baca, just a few years earlier, claimed to be rich in gold, and in fact, he said he saw “cities of gold…” Seven of them..!!! As anxious as the Spanish adventurers were, to seek their fortunes up north, they knew and respected the laws of their King, which prevented them from just sauntering up into the frontier lands at their convenience and enriching themselves of what they might find. Special permission, money, and noble class were the prerequisites to any exploration. The King of Spain assured that his “right to his domain” in all explorations was protected, by requiring that the right man be selected for any explorations. A proven leader whose family would be scrutinized by the Viceroy to assure their finances, and then they would have to pass his “inspection.” Preferably, the man would be of noble birth or of royal “order”, and from a well funded family, to assure that he could afford to pay his way, and all the expenses of his expeditionary force. The King risked only a military escort, and that primarily to protect his investment. Such a man would have to take complete responsibility for the success of any expedition and in the event of success he would enjoy titles, lands, and a good share of whatever treasures the lands had to offer. Should he fail, he would lose all his investment, and probably face the King’s penalty tax for failing, as well as disgrace brought on to his family! Who would risk all this? Knowing with some certainty that the lands to the north were probably impoverished, and knowing that the stories of wealth were spun by the deceiver, Cabeza de Baca, as reported by Coronado, and knowing that the reports filed by that earlier Conquistador painted a dismal picture of hardship to the north, the man who dared was Don Juan de Oñate, the son of the wealthy Zacatecas silver merchant, Cristobal de Oñate. Juan was a son, wanting so desperately to equal or better his father’s achievement of having gained such great wealth in the silver mines. He was also desperately anxious to prove to others that he was a manly conqueror and to become the greatest achiever of them all! And so he filed his petition in 1596, and began the process of selection and approval by the King of Spain. Many troubles arose for Oñate in recruiting soldiers, supporters, wagons, food, tools, and hardest of all, the King’s hesitant approval. Finally, three years after he began the process, and at great expense to him as he continued to add colonists and supplies which the horde of people seemed to consume as fast as he acquired it, word came from the King that he was free to start his march. Finally, yet another Spaniard began his search for riches and a fruitful destiny! And he too, would encounter strange people, customs, and an unforgiving land! A byproduct of the Spanish King’s “need to know” of where all his subjects were at any given time, lest he lose out on any taxes due him, was that everything worth knowing be recorded and filed with his Vicero. As well, the Monks, who also sought equal shares of notoriety and taxes to be had, recorded their activities to their superiors and ultimately to the living icon, the Pope in Rome! In view of all this need to record, the leaders of expeditions usually assigned experienced scribes to record all activities of their explorations. That man would also have the confidence and approval of the Crown, so this would be a man of considerable trust and reputation. In addition to his “official” records, “diaries” were also kept by officers, enlisted men, and all concerned. Today, we have a great amount of information about the people, the times, and the wondrous things they encountered, thanks to the printed record of the day-to-day activities of those early Spanish folk.  Capitán Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá Capitán Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá Capitán Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá It is the writings of one of those Oñate Officers, which is the subject of this story. The writer – recorder - author is that well respected scribe, Don Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá, who was made a Capitán in Onate’s staff in 1596. His later titles and accomplishments would be many. His writings have been preserved in several productions, and in particular in a book titled: “Historia de la Nueva Mexico, 1610”. This particular book is considered “A critical and annotated Spanish / English Edition, translated and edited by Miguel Encinias, Alfred Rodriguez, and Joseph P. Sanchez”. The well educated and well read Villagrá wrote his account of events in a Spanish prose / poetry style. He captioned them as “Cantos”, (songs), which are replete with references to the earliest biblical events and writings of scholars of earlier times such as Pliny, Plato, and others. Villagrá can be considered to be a most reliable and learned observer and recorder of his time. And so it is that the scholars of today, such as those mentioned above, took great respect and care in their treatment and interpretations of Villagrá’s Cantos, from Spanish to English. And that is how they appear in the book mentioned: his entry in the Spanish of that time, and alongside, the English interpretation. The Book – Historia de la Nueva Mexico, 1610 Finally, I draw your attention to Villagrá’s first and second Cantos, in which he writes about the mass of humanity that had assembled at or near what is now El Paso, Texas, known then as “el paso del Norte” and by other names. In referencing their interpretations, Encinias, Rodriguez, and Sanchez, are hereafter referred to as: “the interpretors”, and so we begin.  El CANTO PRIMERO Villagrá entitles his Canto Primero, “Que Declara el argumento de la historia y sitio de la nueva Mexico y noticia que della se tuvo en quanto la antiqualla de los indios, y de la salida y decendencia de los verdaderos Mexicanos”. The interpreters’ English version is: “Which sets forth the outline of the history and location of New Mexico, and the reports had of it in the tradition of the Indians, and of the true origin and descent of the Mexicans.” My interpretation: In his first Canto (Canto Primero and Canto I), Villagrá describes the geographical location of the point of beginning of the Oñate Expedition. In his learned way, he carefully references its location, relative to geographical north – south longitude and east – west latitude with the then known points of the compass and even compares the location on the world globe, with known places in the old world. He equates the location geographically, to Jerusalem by latitude! He also describes the mass of humanity that is the expedition, and even marvels at the attire of some of the characters. Some are well-dressed gentlemen, riding excellent mounts adorned with “finery” and “livery as in the finest courts” which clearly defines to their noble class, while others are fearful looking men, one even wearing the skin of a lion complete with mane! Some wear the skins of striped cats, leopards, and even wolf skins! They carry weapons of all sorts, and banners and standards of all colors and kinds as they slowly move along. It is a fearful and bedraggled looking lot! People, cattle, goats, sheep, and everything necessary to support the expedition walk in unison. At the end of Canto I and in Canto II, which is again, the subject of this article and the beginning of Oñate’s drive north, he describes a terrible apparition! It is the last lines of Canto Primero and the text in Canto Segundo that fascinates me. My fascination is in that although I interpret Villagrá’s notations and descriptions of the “apparition” literally in the same way as the interpreters do, I see through Villagrá’s eyes, something quite different and amazing than they do! Being careful not to show disrespect to those interpreters in any way, I claim the right to my own interpretation and understanding of what Villagrá and the whole camp saw and what he recorded so carefully in the only way he knew how. He compared what he saw to things he could relate to at that time in 1599. In Canto I, Villagrá ends his description of the mass of moving people by stating that as the many people (and animals) trod on over the hard baked ground, they raised a huge cloud of dust. Suddenly, a figure appeared before them, which he describes as looking like an old naked woman: “Delante se les puso con cuydado, en figura la vieja desembuelta, un valiente demonio resabido – cuyo feroz semblante no me atrevo, si con algun cuydado he de pintarlo, sin otro nuevo aliento a retratarlo”. The interpreters write: “There placed before himself, before them by intent, is the form of an old and hag-like woman. A valiant and cunning demon, whose face ferocious dare I not look at, if I must with some care depict it, set out to paint without new strength.” My interpretation: It appears that Villagrá and those with him have come face to face with a being, which he says carefully, or cautiously, appears before them, resembling an old naked hag-like woman. (I think he assumes it to be “feminine” as he can see no male genitalia). His first reaction is to associate this inhuman form with some kind of demon or even the devil! It has such terrible features (cuyos feroz semblantes), that he doesn’t dare assume that it is (the devil), as in his next breath (otro nuevo aliento), he may create it in his mind or in fact, create it incarnate (a retratarlo)! So what is this being that suddenly confronts them? Appearing to look like an old, naked hag? Follow up: In modern times, today, his description takes on the appearance of those ugly little beings who we hear and read about, and who appear to wear a one-piece, pale gray, skin-tight garment if any at all, and who we call, Extraterrestrials!!! CANTO SEGUNDO Villagrá writes the Canto Segundo in the first person, as an eyewitness to what he and others are observing. Again, Villagrá entitles Canto Segundo: “Como se apparecio el Demonio a todo el Campo, en figura de vieja y de la traza que tuvo en dividir los dos hermanos, y del gran mojon de hierro que asento para que cada cual connociesse sus estados”. The interpreters’ English version is: "How the Devil appeared in the whole camp in the shape of an old woman, and of the scheme he had to separate the two brothers, and of the great heap of iron that he left so that everyone might know his true estate”. My interpretation: I think that Villagrá has seen what he (and the others) believe is the devil in the disguise of an old hag-like, nude woman. Although terrified, they courageously stand their ground. Somehow, the entity communicates to them, or they believe they hear it say, that it is going to separate the two “brothers?” It also leaves “un gran mojon de hierro que asento para que cada cual connociesse sus estados”. The interpreters say “he left a great heap of iron”. My interpretation of this “heap of iron”, is that Villagrá is describing a one-piece metal vessel, standing upright. A “mojon” in Spanish, can be a landmark… as in a real estate landmark or marker of the boundaries of one’s lands. The landmarks of old were shaped like an obelisk, and in this case, made of metal. Is this the shape that Villagrá is seeing and can only describe it in a familiar term, like a “mojon de hierro?”  The Being’s Vessel Above is an example of a “mojon”. A Spanish word for a landmark or monument, typically used to mark boundaries of property. Typically they are four-sided, hewn from stone, and pointed at the top to prevent snow or water from settling on its top, lest the water turn to ice in winter and crack, and eventually break the stone. The sides are usually oriented to the four directions of the compass and may contain the owner’s name, coat of arms, and/or the geographical extent of that corner or location of the property. The size of landmarks varies, and the height can be as much as one meter. The sides can be one-fourth that, or per the owner’s specifications. Does Villagrá mean that the creature “left” that mojon de hierro (vessel)? As in, coming out of it? And it is therefore his “estate” or “place of residence?” I think Villagrá could be saying that the entity “exited” from an upright metal vessel shaped similar to a “mojon” and came toward them. I do not interpret his use of the word mojon, as a “heap of iron”, which implies a pile of metal scrap. I don’t believe that Villagrá had that meaning in mind. Villagrá next describes the being as: “Delante se les puso aquel maldito, en figura de vieja rebozada. Cuya espantosa y gran desemboltura, daba pavor y miedo imaginaria. Truxo el cabello cano mal compuesto y, cual horrenda y fiera notomia, el rostro descarnado, macilento. De fiera y espantosa catadura: desmesurados pechos, largas tetas, hambrientas, flacas, secas y fruncidas, nerbudos pechos, anchos y espaciosos, con terribles espaldas bien trabadas: Sumidos ojos de color de fuego, disforme boca desde oreja a oreja, por cuyos labios secos, desmedidios, quatro solos colmillos hazia fuera de un largo palmo, corbos se mostraban: los brazos temerarios, pies y piernas por cuyas espantosas coniunturas una ossamenta gruesa rechinaba, de poderosos nerbios vien assida" . The interpreters write: “That accursed one, placed he before them in the form of an old woman well disguised, whose great and fearful cleverness, doth cause both fear and terror to imagine. He had his gray hair badly dressed, and like a horrible, fierce skeleton, his fleshless and emaciated face, of an expression wild and fearsome, misshapen breasts and dangling teats, starved, flaccid, dry, and wrinkled. Great chest, both wide and spacious, with shoulders terrible, well set eyes sunk and colored as of fire, a mouth small formed, from ear to ear, through whose dry and distorted lips, fangs, just four protruded, and showing themselves in good palm’s length. His arms were fearful, feet and legs, in whose fearsome joints the bones creaked loud. Well set, with muscles powerful. Just as they picture for us and do show, The ferocious person of brave Atlas, upon whose great and robust strength, the great incomparable weight and thrust of highest-lifted heavens doth rest.” My interpretation: Generally, I agree with the literal interpretation of the interpreters, but I feel that looking at the entity through Villagrá’s’ eyes, he sees a living being, with a very small, thin body on the one hand, (desmesurados pechos, largas tetas, hambrientas, flacas, secas, y fruncidas), yet with very broad shoulders bien tradadas, which in Spanish, can mean “shoulders with a brace or apparatus connected to them, or over them, making them look larger than they are”. (Example: in Spanish, un buey tradado, means an oxen with an ox yolk over his neck and shoulders, which can be quite massive).  The Being’s Bodily Appearance Can this mean it was wearing something on or over its shoulders? Like a life support pack of some kind? Villagrá then says he could see “los brazos temerarios, pies y piernas por cuyas espantosas conjunturas, una ossamente gruesa rechinaba” Could this mean the being’s arms were such that Villagrá did not feel they were arms but were exaggerations of arms? Temerarios means overly bold or inconsiderate, or baseless. Perhaps that is how he saw the arms… covered with something that made them look bigger than arms should be? Pies y piernas por cuyas espantosas conjunturas. Villagrá describes the arms and legs as frightening in that the legs seem to be joined or connected to each other, as one… (conjunturas) Could they be covered with some kind of protective clothing or apparatus? Could the being be standing in some kind of apparatus that partially covers his feet and legs? He says that “una ossamente gruesa rechinaba”. He says that one of the “boney” legs or both as one, made a loud creaking, screeching, or whining sound, Could this be the high pitch sound of a propulsion device? Or propelled device on its legs or whatever Villagrá saw and describes as legs joined together? As if to confirm this thought, Villagrá adds to the description of the “legs”, “de poderosos nerbios vien assida”. Could the “powerful nerves, well constructed”, he is describing, be in reality, hydraulic-like tubes or lines attached to the being’s legs, or whatever he is standing on? Can we see through Villagrá’s eyes, in his description, a very frail like being, ugly to them like an old skinny, nude, woman would look, but partially “clothed” in a suit of some kind that has some kind of apparatus on or over its shoulders, and some kind of leggings or apparatus with fluid-like lines attached, that make a whining sound like a motor would make? The Being’s Head Villagrá then describes the appearance of the being’s head: “Encima de la fuerte y gran cabeza, un grave, inorme, passo, casi en forma de concha de tortuga lebantada, que ochocientos quintales excedia, de hierro bien mazizo y amasado.” The Interpreters write: “Upon her head, so great and strong, a huge, enormous weight, almost in the form a tortoise-shell set upright, exceeding some eight hundred quintal weight, of metal, massive and well molded".  My interpretation: Again, I agree with the literal interpretation that the interpreters say Villagrá saw, and would add that again, looking through Villagrá’s eyes in that time, he could only compare what he saw to something he knew, yet ridiculous…a tortoise shell over the being’s head! If Villagrá were living in modern times, he could easily say that the being was wearing a large, shiny clear acrylic helmet, almost exactly like our astronauts wear today. Villagrá next writes: “Y luego que llego al forastero campo y le tuvo attento y bien suspenso, con lebantada voz desenfadada, herguida la cerviz, assi les dijo: “No me pesa esforzados Mexicanos, que como bravo fuego no domado. Que para su alta cumbre se lebanta no menos seays movidos y llamados de aquella brava alteza y gallardia de vuestra insigne, ilustre y noble sangre, a cuya heroica, real, naturaleza, le es propio y natural el gran deseo. Con que alargando os vais del patrio nido, para solo buscar remotas tierras, nuevos mundos, tambien nuevas estrellas, donde pueda mostrarse la grandeza de vuestros fuertes brazos belicosos, ensanchando por una y otra parte, etc.” The interpreters write: “And when he came upon the foreign camp, holding it attentive and in suspense, with a loud voice and unembarrassed, his head erect, he then addressed them thus: “I am not pained, o valiant Mexicans, because, as raging fire never quenched, which rises to its summit high, you are in no way less moved or beckoned by the rude haughtiness and gallantry of your illustrious, grand, and noble blood, to whose heroic royal character is natural, inborn, this great desire, with which you go from the paternal nest, only to seek for lands remote, etc., etc.” My interpretation: It seems that in this lengthy passage, Villagrá writes that the being confronts the very attentive people in camp and speaks to them, telling them that it understands how they feel, compelled to enter new lands and that it is in their nature to do so, given their royal blood, etc…. It seems that suddenly, Villagrá no longer fears or sees the entity as an ugly devil, but now it speaks to them in an understanding tone of voice, empathetic to their cause, agreeing with their right to pursue their search for new lands, etc. Or is Villagrá now writing for the eyes of the King? Or his representative, the Viceroy? Perhaps not wanting to appear less manly for previously being afraid of this being? Did the being really say these things to them? Why would it now seem to agree and invite them to continue into this new land, when at first it seemed so threatening? Villagrá next writes: “Y lebantando en alto los talones, sobre las fuertes puntas afirmada, alzo los flacos brazos poderosos, y dando al monstruosa carga buelo, assi como si fuera fiero yrayo, que con grande pavor y pasmo assombra, a muchos y los dexa sin sentido” The interpreters write: “And raising from the ground his heels, set firm upon his mighty toes, he raised his powerful, mighty arms and giving to his monstrous load a push, as though it were a mighty thunderbolt.”  My interpretation: Villagrá describes a being rising off the very ground, by some “force” emitting from its feet. It raises its spindly, but powerful arms and “lifts” its bulky body, (el monstruosa carga buelo), like a metallic bolt of lighting, leaving them stunned and senseless! Villagrá earlier described a heavy bulky suit over a spindly body. Now he sees the small but heavy being lift off the ground with bolts of lightning emanating from his “feet”. Could the bolts of lightning be exhaust from some kind of propulsion unit? He describes it as best he can. Villagrá next writes: “Assi, con subito rumor y estruendo, la portentosa carga solto en vago y apenas ocupo la dura tierra quando temblando y toda estremecida, quedo por todas partes quebrantada!” The interpreters write: “So with a sudden and horrendous noise, he threw aside the mighty load. And hardly did it strike the flinty earth, when, trembling and shaking all, that earth was broken everywhere.” My interpretation: Villagrá describes as best he can, how as soon as the entity clears his “feet” off the ground, there is a mighty roar which makes the earth tremble and the ground below the entity is blown away in all directions… just like a modern day astronaut blasts off with a shoulder mounted jet-pack, like those presently being tested by our military, and even demonstrated at an NFL football game on one occasion, when the pilot flew all around and over the grandstand spectators! Villagrá continues: “Y assi como acabo, qual diestra Circe, alli desvanecio sin que la viesen, senalando del uno al otro polo. Las dos altas coronas lebantadas. Y como aquellos Griegos y Romanos quando el famoso Imperio didieron, Cuio hecho grandioso y admirable.” The interpreters write: “And when ‘twas done, like Circe skilled, he vanished thence without their seeing him, pointing to one and to the other pole. The two crowns raised on high, just as the Greeks and Romans when they divided the empire famed.” Villagrá continues: “Tan presto como viene, bemos buelve, assi con fuerte bote, el campo herido con lo que assi la vieja les propuso, la retaguardia toda dio la buelta para la dulve patria que dexaban”. My interpretation: Again Villagrá describes what he sees and can only compare it to a great event he knows of: the parting of the Greek and Roman Empire! He sees the being rise and fly back and forth from north to south, (the poles), and as quickly as it goes, it returns, and he sees “las dos altas coronas lebantadas”. He must be seeing the “burst” of flames or exhaust from two jets attached to the back pack the entity is wearing. which to him, from below, look like two shining royal “crowns” glittering up high. The interpreters write: “ Thus in a bound, the stricken camp became from what the woman had proposed to them, all the rear guard did turn again toward that sweet fatherland they’d left”. My interpretation: Villagrá now sees the frightened people in the camp, terrified at the sight of the being flying overhead, to and fro, beginning to turn around and beginning to retreat back to the safety of whence they came. Villagrá now writes, as though a day or more later: “Y por sus mismos propios ojos viendo la grandeza del monstuo que alli estaba. Al qual no se acercaban los caballos por mas que los hijares les rompian, porque unos se empinaban y arbolaban con notables bufidos y ronquidos, y otros, mas espandados, resurrian por uno y otro lado rezelosos de aquel inorme peso nunca visto, hasta que cierto religioso un dia celebro el gran misterio sacrosanto de aquella redencion del universo, tomando por altar al mismo hierro, y donde entonces vemos que se llegan sin ningún pavor, miedo ni reselo a su estalage…” The interpreters write: “There still remains in the same way, the mighty mass which there was placed, in height some twenty-seven degrees and a half more. And there was no man of all your camp who did not stop, astonished, stunned, and almost senseless, considering that same story and seeing with his own two eyes the greatness of the monstrous mass was there. And of the horses, not one would approach it unless one tore their flanks, for some stood on their hind legs, rebellious, with whistling, and snorts, and others, frightened more, did shy suspicious from one side to the other from that enormous mass, such as was never seen. Until one day a certain priest did celebrate the great most holy mystery of that redemption of the universe, taking for altar that same mass of iron, and ever since we noticed that those beasts came without fear or trembling or suspicion to it’s foot”. My interpretation: Villagrá now writes about a huge metal vessel or ship, which now stands in the place where the previous apparitions were witnessed. It rests upright and he measures it in degrees of an angle, instead of measurement of height. Can this mean that the top of the vessel is angularly shaped? Cone-like, as like a present-day missile? And like the mojon described earlier? He says anyone (everyone), from the camp now comes to see it in complete disbelief and amazement. The horses sense something very foreign as they display terrified behavior, rearing up on hind legs and refusing to come closer. Then Villagrá says “a certain priest celebrates a most holy mystery of that redemption of the universe, using the base of the vessel as an altar, and all seems calmed with the animals”. Is the “certain priest” an entity from the vessel? If it is one of the monks among the Spanish, why doesn’t he say it is a monk? And the “celebration of the most holy mystery of the universe”, at the base of the vessel. Is the entity simply disconnecting something or turning something off at the base of the vessel? Such as a motor, which is making high frequency waves, which scare the animals? Does Villagrá mistake his actions as some kind of religious ceremony he is conducting? Villagrá describes it as best he can, when he writes: “and ever since we noticed that those beasts came, (the horses), without fear or trembling or suspicion, right to it’s foot, as to a place which has been freed from some unloosed infernal fury”. It seems that after the “priest” did whatever he did at the base of the vessel, the horses no longer fear it. Note that Villagrá and the people in camp no longer refer to the entity as a devil, witch, or brujo; they now seem to accept that what they have been seeing as something wondrous is apparently harmless to them as they freely come to see and touch the vessel. Villagrá writes perhaps the most telling account of what the “heap of iron” is: “Y como quien de vista es buen testigo, digo que es un metal tan puro y liso y tan limpio de orin como si fuera una refina plata de Copella”. He further describes the purity of the metal, and can only wonder how it could have been created in that primitive land, not understanding that it probably came from beyond our world." The interpreters write: “And I as one who is good witness of that sight, say that it is as pure and smooth a metal, and free of rust, as if it were silver refined at Copella!” My interpretation: Villagrá’s’ description of the vessel’s metal surface speaks for itself. For me, the description is very familiar. For many years, I worked as a machinist and welder for the Boeing Aerospace Company in Seattle, Washington. I taught metallurgy, welding, and fabrication in several Community Colleges in that City for many years. I also worked in an Engineering office designing pressure vessels using various state of the art exotic metals, some that can withstand rust, abrasion, and acids, and remain highly polished. The metal Villagrá describes can only be a highly polished alloy, not of this earth, especially in that day and age. Villagrá now wonders as to the construction of this “mojon” which is in fact, a wondrous craft: “Una refina plata de Copella, y lo que mas admira nuestro caso, es que no vemos genero de veta, horrumbre, quemazon, o alguna piedra con quia fuerza muestre y nos pareca aberse el gran mojon alli criado, porque no muestra mas señal de aquesto, que el rastro que las prestas aves dejan, rompiendo por el aire sus caminos, o por ancho mar los sueltos pezes quando las aguas claras van cruzando..!” The interpreters write: “And what our people wondered most, is that we saw no sort of vein, nor scoria, trace, nor any rock, by means of which we might be shown or see how the great mass could be created there. Because there is no more trace of that, than the swift birds leave traces in the air through which they make their road, or, in the sea, the swimming fish, when they go plying through the waters clean”. My interpretation: Villagrá, again is trying to compare this wondrous metal to something familiar, as he and the others contemplate what he now calls “una refina plata de Copella”, “the finest silver from Copella”, and no longer “un monton de hierro”, “a heap of iron.” He and the others can’t understand how this vessel was constructed. It has no apparent rivets, joints, or seams, (genero de veta), there is no evidence of metal casting materials like sand or clay in evidence, (horrumbre), nor evidence of a smelting fire or oven, (quemazon) where it may have been cast. There is not even a rock with which someone might have pounded the mass into shape. Understandably, they assume someone built the vessel where it stands, as the concept of it having flown there is not a consideration. He goes on to write that there is no trace of its fabrication anywhere, just as one doesn’t see the “trace” or track of a bird flying through the air, or the “trace” or track of a fish swimming through the cleanest water. He is obviously in awe of this mystery. Villagrá next writes that there were stories told by the “antiguos naturales”, the ancient native Indians of the old tribes of Mexico, of people from the far off northland from whom they say they are descended. These people were “como en Castilla, gente blanca, que todas son grandezas que nos fuerzan a derribar por tierra las columnas del “non Plus Ultra”, infame que lebantan Gentes mas para rueca y el estrado”. People who looked as white as those of Castille, of grandeur, just as our memories of those beyond the columns of “Non Plus Ultra”, who were famous for their ability to elevate themselves on platforms! This appears to be a reference to the ancient people of Atlantis, who Villagrá knew of from Pliny and Plato’s writings, and who were said to live beyond the columns or pillars of Non Plus Ultra, (the Straits of Gibraltor.) “The place no one dares go beyond,” where the inhabitants, (Atlantians), (Gentes mas para rueca), were said to elevate themselves on “platforms” (estrados). Finally, at the end of Canto Segundo, Villagrá writes, in reference to the people encountered: “Mas dexamos aquesta causa en vanda, cerrando nuestro canto mal cantado, con aber entonado todo aquello, que de los mas antiguos naturales ha podido alcanzarse y descubrirse”. The interpreters write: But let us lay this thing aside, which needs a story long to tell it all, closing our Canto, badly sung, by having sung quite all of what, by the most ancient natives here, could be remembered and discovered, about the ancient descent. My interpretation: Frustrated, Villagrá writes, “let us lay this event aside, which needs a story long to tell it all.” Obviously, he has seen much he cannot explain and feels it is a story too long to tell to make sense of it, and perhaps because the expedition is now moving on, and he decides to put this experience aside. He says his Canto is “badly sung,” meaning he is obviously disappointed that he could not better explain in words, all he has seen and all he has experienced, that he cannot explain it all as he doesn’t have the experience or memory to relate to, as this is all new to him…. He seems to writes it off as if to say, “Ask the natives… they can tell you more from their memories of their ancient ancestors!” Villagrá ends the Canto Primero with these final words: “De aqueste nuevo Mundo que inquirimos, adelante diremos quales fueron y quienes pretendieron la jornada sin verla en punto puesta y acabada”. The interpreters write: Of this New World which we explore, I shall say later who they were, those who the journey undertook, not seeing it done and ended in a moment. My interpretation: I feel Villagrá says much in his final statement.. “Of this new world,” can mean the world they are entering, meaning New Mexico, or it can mean “the new world of knowledge” he has just entered, in view of what he has just seen: the beings, their flights, the vessel, the lack of anything familiar, the lack of explanations, etc.. Certainly his mind would never be the same!! He says he shall say later “who they were, those who the journey undertook, not seeing it done and ended in a moment…” does this mean he received some knowledge from them as to who they really were? Or does this mean he will share his interpretation of who they were at a later date? Are “those who the journey undertook”, the beings? Or, the people in the caravan slowly traveling north? I think he has learned, perhaps from the beings, that they have traveled far to come to this earth. And he doesn’t understand or can comprehend that thought as he says, “not seeing it done and ended in a moment”. Can this mean that he didn’t see them arrive, so can’t understand how that massive “heap” could have moved through the air and brought them here? And finally, the statement: “ended in a moment”. Can this mean he saw them leave, and as many have reported even today, when the crafts take off, they do so in an instant, almost as if they disappear out of sight! Thus again, his statement: “ended in a moment”. When Villagrá says, “I shall say later who they were”, one might think that at some later date, he wrote more of this encounter, and perhaps then, if that “Canto” or report is found, we will all know more of this strange encounter he wrote of, while on Onate’s Expedition into this land we now call New Mexico. Certainly no dream or made up story of a witch or demon, but the recording of an event that could only be explained in the words and experience of his time. New Mexico is a land which has certainly seen its share of unexplained mysteries, such as at Roswell, Socorro, and in the mountains of northern New Mexico around Dulce, so rich in accounts of sightings of beings and unexplained flying crafts. And so ends this interpretation that I found so fascinating and that poor Villagrá found so mysteriously perplexing! Villagrá gazing skyward as the vessel flies away. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed