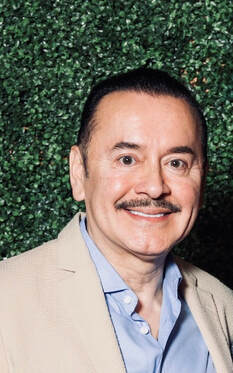

“Mother's Day”by Robert G. Retana The card was made of white construction paper and had a small flower on the front drawn with crayons. Each petal was a different color, and “Happy Mother’s Day” was neatly written across the top of the card. The handwriting was that of a child but neat and precise, nonetheless. Inside the card, the words “from Victor” were written in blue ink. Victor brought it home from school right before Mother’s Day and showed it to his Aunt Dolores. “Can I send this to my mother?” he said. His words pierced Dolores’s heart because she knew how much pain this poor child carried around and how much he would suffer for the rest of his life for things he had no part in. “Yes, you can send it to her,” Dolores responded. “We’ll find an envelope for it and mail it tomorrow morning. She should get it in a few days.” “When can I see her?” Victor asked. “We can go for a visit soon. But she is in Chowchilla, a long way from here, and I don’t know how soon we can take a trip there.” “When can she come home?” “Baby, she might never come home,” Dolores responded. “But she thinks of you every day, and you can visit her there. It’s far, and we can’t go that often to see her. My car gives me a lot of trouble, and it takes forever if we take the bus.” Dolores hugged him, and he hugged her back. Then he went upstairs to change his clothes and play video games before he had to do his homework. Dolores wondered whether she would have it in her to heal this child’s heart or whether the pain he felt would become rage, and he would wind up in prison like his mother. She prayed he would not change and that God would help her know what to do to make things better. Dolores had her own two children and never expected to raise a third. But now that he was hers, she could not help but want to take care of him. No one should start off in life with so much pain and sadness. She looked at the framed picture of herself and Marisa, her younger sister, and Victor’s mother, which she kept on the living room wall. It was taken when they were little girls, four and five years old. They were clinging to their mother, who looked so happy and beautiful. She had long, brown, wavy hair and large expressive eyes, just like Marisa. Both girls were smiling and holding on to their mother for dear life. Behind them stood their father, a tall, handsome, nicely dressed man with thick black hair combed back and a neat mustache that framed his broad smile. Little did they know that soon after this picture was taken, their father would leave home and never return. People said he had another family in Mexico and decided to return there. Others said he was spotted wearing a fancy suit in the bars with a new woman by his side. Whatever the story was, they never saw or heard from him again. It was too much for their mother to take, and soon after he disappeared, she killed herself, overdosing on sleeping pills. Marisa was sent to live with her grandmother, who was too old to control her, and just prayed a lot for her salvation. Dolores went to live with an aunt who took good care of her but could not afford to take them both. The girls cried for weeks when they were separated. Although they kept in close contact, they went their separate ways in terms of lifestyle. Marisa always had boys chasing her, but she never found a healthy relationship. Men just brought her more problems. Dolores was more serious and had a stricter parental figure in her aunt. She could not run with the same crowd or tag along when Marisa skipped school or got a fake I.D. to go nightclubbing even though she was underage. Marisa quickly learned that any shyness or awkwardness she felt would go away when she had been drinking and doing drugs, and her self-esteem was boosted by the attention she got from men, even if it turned out to be more trouble than it was worth. There was always room at the parties for a pretty girl who liked to have a good time. The pain of losing their mother and father and then being separated from Dolores never seemed to lessen for Marisa. She lied, made everything seem great, and gave Dolores expensive gifts and clothes that she could not afford to buy for herself, never explaining how she got them. Marisa could never look her sister in the eye and tell her everything she was caught up in. People said she used men and women to get what she wanted. Marisa would always drive nice cars but never had a job that would allow her to afford them. She dressed in nice, new clothes and always had her hair and nails done. She looked vivacious, but when she drank, the sadness in her eyes was unmistakable. When she visited Dolores, she sometimes slurred her words like she was high but denied she had a drug problem. Dolores begged her not to use drugs when she became pregnant and feared the baby would be born with birth defects. Luckily, he was born a healthy baby boy. Marisa never said who the father was and gave the baby her last name. She named him Victor, after their father, which surprised Dolores since Marisa always said she hated him. “At least this Victor will never leave me,” Marisa explained. “He will always be mine.” Marisa cared for Victor as a baby, but as soon as he could walk, she started partying again. She would leave him with friends and family as often as she could. She would ask Dolores to watch him for a few hours and then not pick him up for a week. Marisa’s heart was not right, and having a baby did not change that. She always showed up with money, a nice toy for Victor, and a long story. Dolores knew Marisa was headed for trouble; however, she never imagined how much trouble was ahead. *** The drive home that night began in the Mission District of San Francisco. Marisa and her husband, Rob, had dinner on Valencia Street. When she took the driver’s seat of their new, black BMW 525i, she made a quick call on her cell phone and then hung up when the call was answered without saying a word. “Who are you calling?” Rob asked. “I want to see if my friend is coming over tomorrow to take me to apply for a job. But I didn’t realize how late it was, so I’ll call her in the morning,” Marisa responded. “Okay. You don’t need to work, but if you want to, if that makes you happy, then you should do it.” About half a mile away, Marisa stopped the car and said the check engine light had come on. “Don’t stop the car here,” Rob said. “This is not the best neighborhood; we can still make it home with that light on.” Just then, a car pulled up behind them. A man quickly approached the vehicle’s passenger side and told Rob to get out. He held a gun pointed at Rob. “Just do what he says,” Marisa told him. He got out of the car and tried to cooperate, not wanting any harm to come to him or his wife. Seven shots were fired as soon as he was out of the car. Three bullets pierced his skull while the rest entered and exited his chest. When the police arrived, Marisa was crying, saying that Rob was her husband and that someone tried to carjack them and they shot Rob. But the car was still there, her purse was still inside, and she was still wearing the expensive diamond wedding ring Rob gave her. Marisa said she had no idea what the suspect looked like or what kind of car he was driving. She had no bruises, although she claimed the suspect hit her and pushed her to the ground so he could take the car. Her demeanor was also strange in that she did not ask about her husband’s condition or come close to his body, maintaining her distance from the crime scene instead. At the police station, she seemed confused and a little bit disinterested. She gave a vague statement to the police but became impatient when pressed for more details. The police did not believe her from the start but had no basis for placing her under arrest. The facts, however, did not match up, as the route she took home was not the most direct route to the freeway entrance, which would lead them to the Bay Bridge and then to their home in the Oakland Hills. Something was up, and Marisa was not a persuasive grieving widow. Rob died from gunshot wounds in the ambulance on the way to San Francisco General. When Marisa was told about his death, she did not cry. She looked more dazed than sad and said she wanted to go home. The police wound up notifying Rob’s family. They would soon learn that he was a 45-year-old executive at a software company in San Jose. He was a shy bachelor for most of his life and never dated much until he met Marisa. He met her at Golden Gate Park one day, where he was walking his dog. She approached him to pet his cocker spaniel. The dog seemed to like her, and Rob let her play with him for a while so he could get a closer look at her. She had long brown hair that was pulled off her face. She was petite, had curves in all the right places, and knew how to show them off. She was someone that people noticed. She was at ease with herself and struck up a conversation with him that flowed in a way his conversations with women never did. Before he knew it, she had given him her phone number, and they agreed to meet for a drink. A drink led to her moving in with him quickly and then getting married in a civil ceremony at City Hall in San Francisco three months later. Rob bought a house in the Oakland Hills for them and gave her use of his credit cards, which she had no problem using. She bought expensive clothes, never worked again, and had frequent calls on her cell phone that she had to take in the other room. He never pressed for details of how Marisa spent her time or his money to prevent her from getting upset. In his eyes, she was a very emotional person with a strong personality and a quick temper, but also capable of moments of great tenderness. Lonely nights alone at home in front of the television with fast food seemed worse to him than putting up with her mood swings. “Everyone can think you’re successful,” he would say, “but when you end the day at home alone, it sure doesn’t feel that way.” His family warned him about her, and she hated his family, saying they thought they were too good for her. Rob tried to keep the peace and wanted to make things work no matter what. He ignored her drinking and tried to bond with her son, hoping that being a good stepfather might score some points with her. It never did. He never knew she was still seeing her old boyfriends, even after their marriage. Nor did he know or want to know who she brought to the house when he was at work. She partied with friends and lovers at home, impressing them with how she lived and telling them that she did not love Rob and would divorce him and collect alimony. They laughed and partied with her, had sex with her, but never imagined how far she would go. The pain and abandonment she felt as a child and the men who used her along the way and then discarded her had caused a change in her. She was once a sweet, sensitive girl looking for someone to love her. Now, she only cared about partying and easy money. An expensive dress, nice jewelry, and money in her pocket validated her in a way that she never felt validated by other people. The pain she felt due to repeated abandonments made her do whatever was necessary to lessen the toxic energy she carried around inside despite the party girl vibe she projected. She had no safety net, so she was not afraid to use any means necessary to get what she wanted. The drugs and alcohol eased the pain but blurred her sense of reality. Her old friends included several shady characters who fancied themselves as con artists and criminals who had gotten away with a lot, even if they wound up doing time for some of it. They would tell stories of schemes that had been successful and large amounts of money that could be made with the right planning and execution. When she told them she did not love Rob and was using him for his money, they encouraged her to get rid of him and cash in, as they were eager to keep her interested so she would continue to supply drugs and alcohol. When she was high, it all seemed to make sense, and she had a feeling of invincibility that a sober Marisa would not have. She just needed to figure out how to get rid of him without getting caught. She spent many hours thinking about how to get it done. When an attorney told her that if she divorced him, she would not be entitled to very much, given the short time they had been married, she began to think that there was no other way to cash in but to kill him. She was not leaving this marriage empty-handed. She would not return to her old life with nothing to show for the time she was married to Rob. Eventually, she persuaded Rob to agree to purchase life insurance policies and mortgage insurance for the house, with her as the beneficiary. Then, before she knew it, the drunken conversations about hiring someone to kill her husband and collect the insurance proceeds turned into a plan of action. Her ex-boyfriend, Alex, who left her several times for other women, was back in her life and was seeing her at her house when Rob was working. She seemed to forget all the times he abused her and left her without explanation. She needed his approval, even after everything he had done to her. His return meant he was wrong when choosing someone else over her. At least, that is the story she told herself each time she took him back. Each knew that even though they both looked good, their days of trading off their looks were ending, and they needed a score to set them up. Rob’s family began to ask questions about Marisa and told him to divorce her before it was too late. Rob’s demeanor towards her changed, and she found out that his parents had arranged a consultation with a divorce attorney. The end was coming, and she needed to act quickly. Marisa and Alex agreed to kill Rob on a dark street in the Mission District and make it look like a carjacking. Marisa would keep the house and the car and most of the insurance. She would give Alex one thousand dollars and the proceeds of one of the life insurance policies Rob had purchased. *** As they rode the bus to Chowchilla, Dolores and Victor tried to keep cool in the sweltering heat. It took several hours to reach the Central Valley. As the bus exited Highway 99 and went east on Avenue 24, Dolores was glad the trip was almost over. Victor needed to use the restroom, and she needed to get this over with. Some things needed to be said, and she hoped she had the strength to say them without making things worse. The bus was filled with families of prisoners who seemed anxious to get there. However, their collective enthusiasm was tempered by the realization that they were headed to prison. Above the almond trees, they could see the large complex, Valley State Prison for Women. It looked almost like a campus if it were not for the razor wire. It took them an hour and a half to work their way to the front of the line so they could be “processed.” As they passed through the metal detector, they removed their shoes and were searched by prison guards. Dolores almost did not believe they would search Victor, an eight-year-old boy, but figured they had seen it all and had no reason to trust anyone. They were assigned a visiting table, and when Dolores first saw Marisa, she was shocked. Her hair was cut short and combed back off her face like a man’s. The baggy orange pants and top were in stark contrast to the stylish way Marisa dressed on the outside. All the make-up and embellishments she thought she needed were gone, yet the beauty of her bare face was still unmistakable. “Mom!” Victor shouted when he first saw her, apparently not noticing the change in her appearance. She hugged him awkwardly and sat him right next to her. Marisa was happy to see her son and sister but was ashamed that they would see her like this. Marisa asked Victor about school and his friends and whether he was minding Dolores. He then asked her, “When will you come home?” After a long pause, Marisa responded. “I don’t know, mijo. Not for a very long time.” “Why do you have to stay here so long?” Marisa froze for a minute, not knowing what to say. When she was arrested, Victor was being cared for by a friend. Although he had visited her in county jail and had been to Chowchilla once before, she never explained why she was incarcerated. She never asked what Victor had been told by family and friends. She tried not to think about it and prayed that one day she would find a way to explain to him why she had been sent to prison. “It’s complicated,” she told him. “They said I did some bad things, and I’ll be here until the situation gets straightened out.” Tears began to fall from Victor’s eyes as he listened to his mother. He knew what she had done because the neighborhood kids had no problem telling him, having heard about it on the news. He knew Rob was dead and that his mother was the one who had him killed. He heard it many times from various people but never told anyone that he knew. This caused bouts of sadness and anxiety which made him introverted. “People say bad things about you, but I don’t care what they say,” Victor told Marisa. His voice was trembling. “I want you to come home so we can be together like before. I miss you.” Marisa did not know what to say. She hugged him until she was told to stop by a prison guard. Here, visitors may briefly embrace their loved one upon greeting and again upon exiting the visiting room. Anything more was deemed “excessive.” After a long silence, Dolores told Victor to get some food from the vending machines. She gave him several dollar bills to buy junk food, the only thing available to the prisoners and their visitors. “Bring your mom something to eat,” she told him. When he ran to the vending machines, a small line of people was waiting their turn. Dolores hoped this would occupy him for a little while so she could say what needed to be said. “He misses you so much.” “I know he does,” Marisa responded. “He writes to you and makes cards for you, and you never respond.” “You know I was caught up in the trial. Then I was sent to the reception center for ninety days to be evaluated. Then they sent me here. I had to get used to being here. It’s not easy for me. Don’t make it worse by coming here to give me head trips.” “You’re his mother,” Dolores responded. “You didn’t think about him when you were scheming with Alex. You just thought about yourself and all the things you wanted. Now those things are gone, and all you have left is a little boy that misses you.” Marisa remained silent, not knowing how to respond. “Listen, I am not here to give you a hard time. You know you can count on me to care for him and be good to him like he was my own son. But I’m his aunt, and he still needs his mother.” “What good am I to him behind bars?” “I don’t know what to tell you, but you can’t keep trying to take the easy way out. He’ll grow up angry and hate you if you keep ignoring him. You have to be a mother to him from inside here because you may never come back out. I am telling you this so your son can know who his mother really is. He’ll find newspaper articles when he gets older, and, as you heard him say, people will tell him what happened. Is that what you want him to know about you?” “But I told you, I didn’t kill him.” “Marisa, it doesn’t matter; you were mixed up in it, and Rob is dead. You were convicted. Alex testified against you to save himself. Things might have turned out differently if you had spent more time taking care of Victor instead of looking for your next score. Have any of your friends visited you?” “No,” Marisa responded. Tears began to flow from Marisa’s eyes, and she began to look at the floor. “You were the lucky one,” Marisa told Dolores. “My aunt loved you and took good care of you. My grandmother didn’t want to raise me. She did it because she had to. She always wanted to be in church. She never talked to me. She just kept telling me to get saved and accept Jesus. You have no idea how many times I have been abused. I finally decided I wanted to be the one to take advantage of others. It all made sense to me when I was using. But I know I was wrong, and I’m paying for what I did.” “I didn’t come here to make you feel bad,” Marisa responded, “but being a mother to Victor is more than just tattooing his name on your chest. He needs to know you love him and care how he is.” “I just don’t know how. My mother wasn’t around, so I never learned how.” “Well, you have plenty of time on your hands to learn,” Dolores said. Victor came running back, his hands filled with bags of potato chips, candy bars, and soda. “Mom, here are some Cheetos for you. I know you like them.” “Thanks.” “Why are you crying?” “I’m crying because I am happy to see you.” “Did you get my card? “Yes, it made me very happy. It made me have a nice Mother’s Day even inside this place.” “My teacher said I’m a good artist.” “You are. Thanks for thinking about me. It’s hard for me to write to you because I sometimes don’t have much to say. Nothing good happens here. But I will try to write to you. Send me some pictures of you when you have a chance.” “I will, Mom.” Dolores looked around the visiting room and saw several inmates who seemed to be visiting with their children and other family members. Some kids were younger than Victor; others looked like teenagers, almost ready to become adults. She thought about the amount of hurt that gets passed down from one generation to the next. She often wondered how intense the pain must have been for their mother when she swallowed the sleeping pills and made her two daughters orphans. Had she known that one of those daughters would wind up in prison for life, would she have found the strength to survive? Would she have continued to be a mother to her daughters and keep them on the right track? She wondered if Marisa had considered all the pain and sadness that Victor would endure, would she have stopped herself from getting caught up in a man’s murder? Marisa had a lot of time to think about these things while behind bars. She realized that she had left her son without a mother, much like what happened to her when she was a young girl. It was the last thing she would wish on anyone, much less her own son. Love, it seemed to Marisa, was transitory. You can’t count on it from one day to the next. Victor was the exception to that rule, yet she had ruined his life with her actions and did not know how to make it right. The guilt for what she had done to Rob and Victor was almost unbearable. Just then, Dolores saw Marisa peering at her through the brown eyes she had always used to her advantage. She was stripped of all embellishments now, and all that was left was a battered soul in prison clothes. Next to her was a little boy who looked a lot like her. His happiness at being with his mother would be replaced by tears when he was in bed tonight, knowing that his mother would probably never come home. The three of them sat silently for a few minutes, not knowing what to say. They heard the loud voices and chatter of the other inmates and visitors around them. They all seemed to know what to say and could be heard carrying on. But the three of them sat there and looked at each other, unsure how to relate to each other under these circumstances. When it was time to leave, they hugged each other tightly, and Victor did not want to let go. “Thanks for bringing him and coming to see me,” Marisa said. “Of course,” Dolores responded. “Let’s take this one day at a time. Un día a la vez.” Dolores took Victor’s hand and walked toward the exit. The Central Valley’s overwhelming heat was waiting for them outside. She wiped the perspiration from Victor’s forehead. The heat was nothing compared to all the pent-up emotions in the visiting room. “Don’t worry mijo,” Dolores said to Victor. “If there is anything this family knows how to do, it’s getting through hard times.”  Robert G. Retana is an attorney living and working in San Francisco. He is Chicano, originally from the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles, as well as a Tribal Member of the Texas Band of Yaqui Indians. He lives with his husband, Juan Carlos, and their faithful companion, Tigre, a dachshund mix. Robert’s short story “Leaving Boyle Heights” was published in the Latino Book Review Magazine in 2021. He is a fan of the arts and currently serves as a Board Member of the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts in San Francisco. As a writer, he seeks to tell stories from marginalized communities that are often left untold.

0 Comments

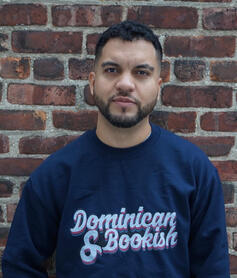

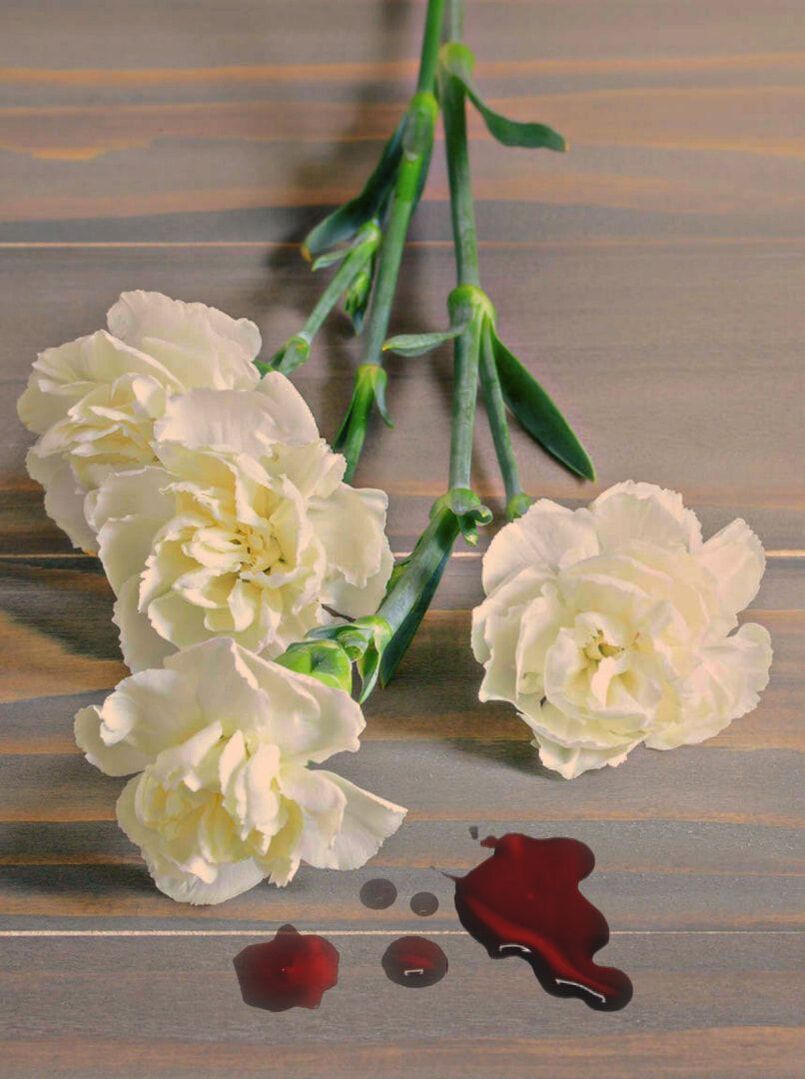

Un jardín de claveles blancosPor Alex V. Cruz El chico de boca rosada le mordió los labios mucho antes de conocerlo en persona. Ocurrió en un sueño, pero Lucas no lo comprendió hasta el siguiente día que, mientras caminaba con la boca sabor a sangre coagulada, lo vio andar los pasillos de la universidad Utesa, recinto Moca, como si nada hubiera ocurrido. Lo conoció por sus labios, largos y delgados como orugas de polilla, y por la manera en que caminaba, pecho alto y espalda recta como si llevara la torre Eiffel metida por el culo. Sus ojos las aguas azules del mar mediterráneo, y su pelo carbón carecía la textura característica de pelo malo. Se llamaba Mateo, y Lucas lo supo por las olas de bochinches en la que navegaban las chicas que lo veían caminar por los pasillos ardientes de la pequeña universidad cibaeña. Lucas, con la punta de su lengua, pasó el día jugando con los agujeros que dejaron los dientes de Mateo en el adentro de su boca. Ya no sentía el dolor naufragante de la mañana, pero aún estaba ahogado en el sabor metálico cliché de la sangre. Cuando terminó su día universitario, se acostó en uno de los bancos por el jardín principal de aquella institución, donde podía ver las nubes oscuras contemplar cómo y cuándo arruinarían el día de los jornaleros diarios. “Nos conocemos,” Lucas escuchó a alguien decir, y no tuvo que moverse para saber que era el chico español que traía a todos locos. Sus eses agudamente pronunciadas y el intercambio de la ce por la ze lo delató casi instantáneamente. “No creo,” dijo Lucas, sentándose en el banco y mirándolo a los ojos, porque de que otra manera iba a explicar que lo conoció en un sueño, que todavía lleva el sabor de su boca y sus dientes marcado bajo sus labios. En lo profundo de sus entrañas, en un lugar cerquita al corazón, cuyo latía como locomotora del siglo XIX, llevaba la memoria de la humedad de su piel. “Sabes,” dijo Mateo, “eres muy atractivo…” Lucas perdió el contacto con los ojos de Mateo. Sus cachetes sonrojaron bajo la melanina diluida de su piel. “… para ser dominicano.” Mateo continuó por su camino, el viento jugando con su pelo y sol adorándolo. Lucas, aún sentado en su banco, vio como un chico, quien él conocía de cara, pero no de nombre, caminaba con su mochila a medio hombro, y su camisa ensangrentada en el pecho. La porción inferior de su boca totalmente devorada, y su espalda sudada. “Ese seré yo mañana,” dijo Lucas. Las primeras gotas del diluvio de esa noche se encunaron en el pelo crespo de Lucas, y supo que era hora de echar camino a casa, donde su madre, con sus huesos de osteoporosis, lo estaría esperando con la comida servida en la mesa, y con el orgullo de ver a su hijo universitario plasmado en su cara. *** Se esperaba el tercer huracán de esa temporada, y Lucas se aseguró de llevar en su mochila la sombrilla que no podría usar por los fuertes vientos. También encontró la bufanda olvidada de su primo americano y la envolvió en su cuello bastante veces para cubrir la sangre que caía por la falta de toda su mandíbula y parte de su cuello. No quería ensangrentar el examen de Civilizaciones Mesoamericanas que tenía esa mañana. Ya el maestro se las traía con él y no quería darle más pretexto para que le reprobara la clase. Lucas llegó tarde a clase. El carro público de infinita capacidad que tomó esa mañana se averió a muchas cuadras de la universidad. Entre los fuertes vientos que amenazaban hacer volar esa bufanda teñida de sangre y el agua percusionista, Lucas pasó por el puertón principal sin despertar el guachimán que protegía la universidad para que nadie la atacara en sueños. Los pasillos ya estaban vacíos y solo quedaba el mal olor de almas y cabello mojado. Se encontró con Mateo, nariz perfilada y pelo brilloso, que lo miraba por debajo de sus pestañas. “Quiero más,” él dijo, y fue en ese momento que Lucas reconoció que Mateo lo estaba esperando. La sangre hecha para el sonrojo brotó por la carne desgarrada de donde debía estar la mandíbula, enchumbando aún más la ya pesada bufanda. Lucas desenvolvió la bufanda poco a poco hasta revelar su labio superior y brotes de sangre fresca y coagulada. Mateo se le acercó y, con su lengua larga y puntiaguda, lamió la cara de Lucas por la frente y bajo las sienes hasta encontrar en su cuello un pedazo de piel aún no destripada por sus dientes y empezó a comérselo a mordidas, deleitándose de su piel morena. Una chica, que salió de un salón de clases, gritó y se desmalló al ver tanta pasión entre los chicos. A Lucas no le quedaba nada en el cuello ni en la parte superior de las clavículas más que esa poca carne rosada y obstinada que no quería desprenderse de los huesos blancos. La bufanda ya no podía cubrir su cuello completo y temía que sus compañeros pensara que parecía zombi de una película de terror. Decidió tomar el día libre. De todas maneras ya era muy tarde para tomar el examen de Civilizaciones Mesoamericanas, así que regresó a la parada de carros para ir a casa, pero los choferes, al ver el derroche de sangre por todo su cuerpo, le negaron la entrada y no tuvo mas que irse caminando entre el viento, que soplaba tan fuerte que levantaba los vehículos y los hacia llegar rápido a sus destinos. *** En casa, donde Lucas puso sus libros abiertos en la mesa coja para que secaran, su madre lo esperaba mientras revolvía el sancocho de tres días en la gran paila de aluminio. “Mira la televisión,” dijo ella, apuntando con los labios al televisor que usaba de antena un paraguas para desviar el gotero del techo de zinc. “El ojo llega hoy y va acabar con todo.” Lucas temía que cancelaran las clases. Temía que no iba a poder ver a Mateo. Temía que no iba a sentir sus labios sobre su carne cruda. Esa noche, entre las fuertes ráfagas de viento, la inagotable lluvia, y los macos escabulléndose entre las tablas de madera buscando refugio, Lucas soñó de nuevo con el chico blanco de la escuela. Este le devoró el pecho y el brazo izquierdo dejándolo en huesos y tendones. Lucas despertó, solo su habitación quedaba en pie. El resto de la casa y su madre se los llevó el huracán y nunca fueron encontrados. “Maldición,” dijo Lucas. “Casi no me queda nada que ofrecerle a Mateo.” Lucas, sin nada mejor que hacer en aquel pedazo de casa que espantar las incansables moscas, se puso su mejor ropa, la que le enviaban los primos y tías de Nueva York, y le envidiaban sus compañeros. Perfumó las llagas que cubría la carne mal comida de su cuello sintiendo el breve picor del alcohol tocando sus heridas y emprendió camino hacia la universidad con la esperanza de ver a Mateo, porque aunque no hubiera clases por la destrucción que dejó el huracán, tenía más oportunidades de verlo en las calles de Moca, que en su pequeño y aburrido pueblo. Lucas llevaba su cabeza en alto, balanceada en casi los huesos cervicales, y con una sonrisa solo en lo que le quedaba de labios, navegaba los obstáculos dejado por el huracán. Ni los postes y cables eléctricos, ramas y árboles, hojas de zinc y cuerpos moribundos pudieron borrar su buen humor. Tenía el presentimiento de que no solo encontraría a Mateo en la universidad, pero que ese día el chico de pelo bueno terminaría el festín que era su cuerpo. Entrarían a un salón vacío y por fin Lucas y Mateo serían uno en un mismo cuerpo. Le tomó horas llegar a la universidad. Su ropa toda sudada y ensangrentada. Limpió el banco, donde tuvo ese corto dialogo con Mateo, de las hojas lloradas por los árboles que aún quedaban en pie. Se sentó y esperó y esperó hasta que anocheció. Mateo nunca llegó. Lucas amaneció sentado, espalda recta, en el mismo lugar donde esperaba a Mateo. No durmió, no soñó, solo esperó. Esa mañana, con la salida del sol, llegaron las moscas fastidiosas que le serenaban constantemente sus oídos. Lucas estaba cubierto de ellas, quienes lamían su carne y ponían sus huevos. Él no podía espantarlas, su columna dorsal estaba tiesa, no podía mover ni siquiera su cuello. Pero por fin lo vio. Mateo, el único en la universidad, llego a verlo. La perfecta nariz de Mateo se arrugó al acercarse a Lucas, quien parecía carne seca al sol. Lucas intento sonreír con lo que le quedaba de labios, pero era difícil al ver la cara de disgusto de Mateo. “Que patético eres,” dijo Mateo. “Me das asco.” Lucas miró como el joven europeo tomaba su alrededor, el desastre dejado por el huracán. Él vio como Mateo nunca perdió de su cara la revulsión que sentía por lo que veía, por la tierra que pisaba. Lucas entendió que ya este sitio lo aburria. Ya la gente le molestaba. Lucas sabía que Mateo iba hacer lo que los mismos dominicanos no podía. Iba a tomar sus cosas e irse a otro lugar por otras aventuras. Buscaría a otro que devorar. Lucas no pudo moverse de ese sitio. Allí quedo como monje en meditación. Los compañeros le traían flores y le hicieron una tumba. Cuando sus huesos se hicieron polvo, fabricaron alrededor del banco un jardín de claveles blancos. White Carnationsby Alex V. Cruz The slender-nosed figure sunk his teeth into Lucas’s lips before their first encounter. It happened in a dream, and Lucas could not fully grasp what had occurred until the following day. He wandered about with the lingering taste of clotted blood when he noticed the guy strolling the hallways of Utesa University without a care in the world. Lucas recognized him by how he strode along, chest puffed and back straight as though the Eiffel Tower were lodged up his ass. His eyes, waters of the Mediterranean Sea. His sultry lips were like long, thin caterpillars. His charcoal hair lacked the texture of “bad” hair. Lucas learned through the undulating waves of gossip that swept through the university that his name was Mateo. The news propagated and intensified with each new flock of girls and guys that gawked from afar as he navigated the sweltering hallways of that small Cibao university. Lucas traced the wounds on his lips with the tip of his tongue, no longer plagued by the agonizing sting of Mateo’s bite. Still, he was intoxicated by the rusty taste of blood. After an exhausting day of classes, he lay on a hard concrete bench by the school’s central garden, peering at the sky as the dark clouds brooded over the ideal time to ruin the life of the daily commuters. “We’ve met,” Lucas heard his voice, and without a glance, he knew it was the Spaniard speaking—the one that caused the entire academy to spawn in a frenzy. The way he pronounced the “S’es” and substituted the “ce” sound for “ze” immediately gave him away. “I don’t think so,” responded Lucas—sitting up on the bench to face him directly—because how could he explain that they had already met in a dream and he could still savor his lips? Deep within his pulsating heart, he suppressed the memory of Mateo’s damp skin, which throbbed to the cadence of a nineteenth-century steam engine. “You know what,” said Mateo. “You’re handsome…” Lucas eluded his gaze, finding refuge in passers-by. His cheeks reddened under the diluted melanin of his skin. “…for a Dominican.” Mateo continued on with his day. Lucas was engrossed by how the wind tousled his hair, and the unforgiving sun chose only to caress his delicate pale skin. He fixated on his swaggering stride until the Spaniard was entirely out of sight. A group of chattering students exited the school and Lucas recognized a class peer. His backpack carelessly hung loose off his shoulder, and his disheveled clothing belied his usually compulsively neat attire. His shirt was bloodied and torn near the chest area. Remnants of his jawbone, freshly nude of flesh, glistened like ivory, and his entire chin and lower lip were gone. Lucas felt a strong pang of jealousy but was comforted by the anticipation: “That’ll be for tomorrow.” Lucas hesitated to leave where he and Mateo first engaged, but raindrops began to penetrate his spiraled locks of hair. It was time to go back home where his mother would surely be anticipating his return with a hot meal set on the table for her college son, pride plastered on her face. *** The third hurricane of the season was approaching. Lucas packed an umbrella and rummaged through his chest of drawers until he found the old, forgotten scarf belonging to his cousin in America. He shrouded his neck as crimson excretions oozed from his shredded skin and absent jaw. Lucas didn’t want to stain the Civilizaciones Mesoamericanas exam the professor had prepared for class. The small and rickety public car broke down on the side of the road mere blocks from the academy. Lucas squeezed passed the other passengers and pressed on, his back hunched against the battering winds and hailing rain droplets, a warning that the hurricane would soon anchor. He reached the main gate, where the watchman slept through the howling storm, fiercely safeguarding the school in his dreams. The stench of decaying souls and damp hair permeated the empty halls. Thin-nosed Mateo, with glistening hair, leaned against the wall and gazed directly at him from underneath his thick lashes. “I want more,” he said. Lucas realized that Mateo was waiting for him. The blood intended for the blushful reddening of desire gushed from his missing mandible and torn flesh, saturating the scarf. Mateo unwrapped Lucas’ scarf unveiling the vestiges from the previous night’s feast. Mateo pressed closer and, with the tip of his tongue, caressed Lucas’ face around his forehead to his temples, exploring down the untouched skin near his collar. Mateo’s mouth widened, his teeth scathing Lucas’s flesh, and with firm pressure, tore a mouthful. An approaching schoolgirl shrieked and fainted at the sight of such passion. Lucas felt for his flesh, his fingers encountered but a stubborn thin layer coating his white bones. His scarf was deemed useless and forgotten on the dirty floor of that school to later become the most beautiful red rose. Already too late to take the exam, and with the professor fixed on failing him, Lucas embarked on the long journey home. *** At his house, he set his soaked books on the flimsy table. His mother stirred the sancocho in the large aluminum pot. “Look at the news,” she pointed with her puckered lips. “The eye of the hurricane will hit tonight and destroy everything.” Lucas panicked at the thought of classes being canceled, fearing he would miss Mateo’s lips all over his raw flesh. Lucas dreamed of him that night, sleeping through the blustering gusts of winds, endless rain, and the macos that squeezed between the wooden planks of the house and searched for shelter. In his dream, Mateo devoured his chest and left arm, and left only bones and tendons. That morning, Lucas awoke to the house and his mother swept away by the powerful gust, never to be found; only his room standing. “Shit!” said Lucas, discovering what was left of his body. “I have nothing left for Mateo.” With nothing better to do than swat tireless flies, Lucas laid out his finest clothes, the ones sent by his aunts from Nueva York, envied by classmates and others. He poured cologne on the exposed ribcage held together by the half-eaten flesh, indulging in the brief sting of the alcohol infiltrating his wounds. Classes were suspended due to the destruction of the hurricane. Still, his chance to see Mateo walking the streets of Moca was better than staying in his lifeless town. His head held high, balanced on bare bones, and a contrived smile with what he had left of his upper lip, Lucas navigated the remnants of nature’s wrath—electricity poles and cables, branches and trees, and corrugated metal and corpses. He was confident he’d see Mateo and was convinced the thin-nosed slick-haired man would continue feasting on his body. They would stow away in an unlocked room and become one in the same body. After hours of trekking to the academy, Lucas’s clothes were a spectacle of sweat and blood. With his one hand, he swept away the leaves on the bench and sat down as best as his weak body would allow. Lucas spent the night on the bench, his back stiffened by dry flesh. Refusing to sleep, to dream, he simply waited. Mateo never showed. With the sunrise, a legion of flies arose, competing for a nip of rotting flesh and repulsive enough to lay their eggs. His body hardened like meat hung to dry. But finally, just as Lucas was beginning to lose hope, he came. His perfect nose wrinkled as he neared Lucas. With the few teeth he had left, Lucas tried to smile but quickly became disheartened as he caught the look of disgust on Mateo’s face. “Patético,” said Mateo. “You sicken me.” The young man skimmed his surroundings and the devastation left behind by the hurricane. Steadfast and beyond reproach, Mateo’s revulsion never faulted; Lucas now understood that this place bored him, the people pestered him, and he was repelled by the soil he stepped on. With deep, inconsolable grief, Lucas knew Mateo would do that one thing Dominicans themselves could not; he would search for adventure in unexplored lands and find himself new flesh to consume. Lucas froze at that moment and never moved again. The world around him retook its rhythm. Classes resumed and Lucas's fellow college mates purchased a tombstone and planted white carnations around the rustic bench where his bones turned to dust.  Alex V. Cruz es un escritor dominicano de ficción especulativa nacido en la ciudad de Paterson, Nueva Jersey. Él es graduado con honores de la Universidad de Columbia en la ciudad de Nueva York con licenciatura en Escritura Creativa y Estudios Hispanos. Actualmente está trabajando en su master de la Universidad de Nueva York (NYU). Alex ha asistido a los prestigiosos talleres de escritura Clarion West 2022 y Tin House 2021. Alex comparte su conocimiento sobre la publicación de cuentos con su comunidad de escritores dominicanos impartiendo clases gratis en la plataforma de Asociación Dominicana de Escritores (@dominicanwriters). Sus cuentos pueden ser encontrados en las revistas SmokeLong, Acentos Review, LatineLit, y pronto en Azahares. También él cuenta con un cuento en Quislaona: A Dominican Fantasy Anthology. Pueden encontrar a Alex en las redes sociales Instagram, Twitter, y Threads usando @avcruzwriter. Alex V. Cruz, a Paterson-born speculative fiction writer with Dominican roots, writes short fiction in both English and Spanish. Graduating Magna Cum Laude from Columbia University, he holds a degree in Creative Writing and Hispanic Studies. He is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing in Spanish at NYU. Notably, Alex is an alum of Clarion West 2022 and a member of Tin House's 2021 Young Adult Workshops. His works have been published in notable online magazines such as Quislaona: A Dominican Fantasy Anthology, SmokeLong, Acentos Review, LatineLit, with two forthcoming stories in Azahares. He is an active member of the Dominican Writers Association, passionately supporting fellow Dominican writers by teaching free publishing classes. Alex is dedicated to sharing his knowledge and empowering his community of writers. Join him on Instagram, Twitter, and Threads using the handle @Avcruzwriter. A Walk on Luna Streetby Kim Vázquez Flora didn’t remember falling asleep, but she must have because she was suddenly startled awake by someone calling her name. “Flora.” She heard it again and looked around. It sounded like her brother’s voice calling out to her, but that was impossible. He had been dead for over thirty years. Voices drifted down from the roof where the rest of her family was watching the sunset. And Flora put her hand on her chest, forcing herself to relax. That’s all it was, her family calling to her. Her mind was playing tricks on her, making her believe she heard her brother’s voice. Flora looked over at the stairs that led to the roof. Maybe she should have gone up there after dinner. One of her favorite things was sitting with her son and grandchildren to watch the sunset. And if she were with them now, she wouldn’t be sitting here thinking she had heard the voice of a ghost. But she had been tired and wanted to relax on the couch and enjoy the warm evening breeze. Besides, she had seen enough sunsets in her life. At ninety-six, she earned the right to do what she wanted. Flora had spent her whole life working hard, and she was tired, so tired. And that’s what she told her son earlier when he tried to insist that she join them on the roof. “Flora, vente.” She heard it again. It was louder this time. She wasn’t half-asleep, and she was almost positive that it was Antonio’s voice. “Except he’s dead,” she told herself. The setting sun streamed through the large wooden doors that led to the balcón, and a memory of Antonio waiting for her came with it. He was in front of the house on Luna Street where they had grown up and sounded a little annoyed as he called out for her to hurry. Papá was forcing him to take Flora with him and his friends to the movies, and he was not to let her out of his sight. Papá always made Antonio take Flora with him. Antonio might not have liked it too much, but Flora loved it. And as she ran down the stairs to meet him, she smiled. After the movie, she would get him to take her for ice cream. Antonio complained, “Te tardastes mucho.” He told Flora she was slow and he didn’t like being late. But he always said the same thing. Then Antonio would smile. And it was always the same sly smile like he knew something that she didn’t, a secret she would love. The sun had almost set, its light was a deep orange, and it covered everything in its glow. Flora felt almost like she was in a dream as she pushed herself up and stepped onto the balcón. She wanted to see where that voice calling out to her was coming from even though she was half-blind and wouldn’t be able to see too far. Sure enough, there was no one on the street. Flora was sure of it, and she wasn’t surprised. “Inventos míos,” she mumbled under her breath, and for a second, she wondered if she was starting to lose her mind. Or maybe she was just tired. She had been tired a lot more lately. She also had been thinking about the past a lot more. That’s what it was, Flora told herself. She was letting her memories get to her. She took a deep breath and shook her head. Then she told herself to leave the past behind, where it belongs. Those times are over and gone. She headed back to the couch, then looked up at the ceiling and said a little prayer just in case she was losing her mind. “Que sea lo que Dios quiere,” she mumbled. “Mami, ¿estás bien?” She heard her son call out from upstairs. “Sí,” she called back. “I’m just tired,” she thought to herself as she grabbed one of the throw pillows she had made off the couch next to her. A thread was loose, and she tried to see where it was coming from but couldn’t make it out. Maybe tomorrow she’d sit at the sewing machine and fix it. She hadn’t done any sewing in a while because of her lousy eyesight. And that was a shame because sewing was her lifelong trade. Gracias a Dios, she had learned one. It saved her when her husband took off with another woman, leaving Flora alone and afraid in New York to raise two young boys by herself. But none of that mattered now. It was over. She had survived and had even come back to Puerto Rico. Flora stretched her legs out. She should go to bed, but her exhaustion was overpowering. She felt it in her bones. Besides, a part of her enjoyed the warm breeze coming in from the balcón. It made her feel safe and comfortable. There was always a lovely warm ocean breeze that made its way down Luna Street in the evening, and she had loved it since she was a child. She closed her eyes and felt her body relax. Just then, her brother’s voice called out again. This time she jumped up quickly and practically ran to the balcón. She surprised herself with how fast she was able to move. She looked out at the street and saw a man standing below. He waved at her. And he seemed familiar, but she couldn’t see his face clearly. “Flora vente.” The man called out, and Flora was sure that it was Antonio’s voice. The man waved, and Flora stood frozen to the balcón’s handrail. She had a feeling in her chest that made her want to go downstairs and see the man, but a voice in her head was telling her not to go. Flora decided to ignore the voice in her head and go with the feeling in her chest. She called out to her son, “Vengo ya,” and rushed out the front door. Usually, Flora held onto the handrail tightly as she made her way down the stairs, but this time it was almost like she was a kid again. Her steps were steady and confident. She smiled and went faster. Flora stepped onto the sidewalk and looked around for the man, half expecting him to be gone. He stood on the corner and waved to her. She squinted, trying to see him clearly. A breeze made its way down Luna Street and brushed against her skin. She felt refreshed, almost invigorated. The tiredness she had been feeling before was gone. He was leaning against the wall waiting for her just like he used to do. The closer she got to him, the clearer her vision. He had the same angular face she remembered, and his hair was dark and messy. Antonio smiled at her, “Por fin llegastes.” And it was the same smile he had always had. Like he knew a great secret that Flora was going to love. Flora stopped and looked up at him. “¿Cómo? How are you here?” His eyes sparkled like she remembered, “I was waiting for you. Te tardastes mucho.” She smiled at him and felt the tears filling her eyes. It felt like he had never left. “Vente,” Antonio held his arm out so she could grab ahold of it, and she looped her arm through his. “Mami, ¿estás bien? Flora heard her son’s voice calling out to her. It sounded so far away. She turned to look behind her and felt an ache in her heart. Antonio looked down at her and patted her hand to reassure her. She nodded, “Que sea lo que Dios quiere.” Then she turned back and smiled. She was ready for her walk on Luna Street.  Kim Vázquez grew up in Puerto Rico and moved to New York to study Dramatic Writing at Tisch School of the Arts, NYU. The lack of representation and diversity in children's books drove her to write a middle-grade Latinx mystery that she is currently querying while she works on another. She's had various articles curated and published on Medium, including “Green Plantains and Memories of mi Isla” and “An Afternoon in la Plaza del Mercado.” She's also had a short story, “The Lady in White,” published by the Acentos Review. Winner Extra Fiction 2022"La Elotera" |

| Gloria Delgado, born and raised in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, is the daughter of a Mexican father and a Hawaii-born Puerto Rican mother. She and her husband live in Albany, California. One of her stories, “Savanna,” was included in the Berkeley Community Memoir Project’s recently published collection, “A Wiggle and a Prayer.” This is her fourth story for “Somos en escrito.” |

**Painting of San Antonio de Padua, patron of the poor, by Micaela Martinez DuCasse, the daughter of Xavier Martinez, a well-known Mexican artist who spent much of his life in California. Ducasse also taught classes at Lone Mountain when Delgado was a student.

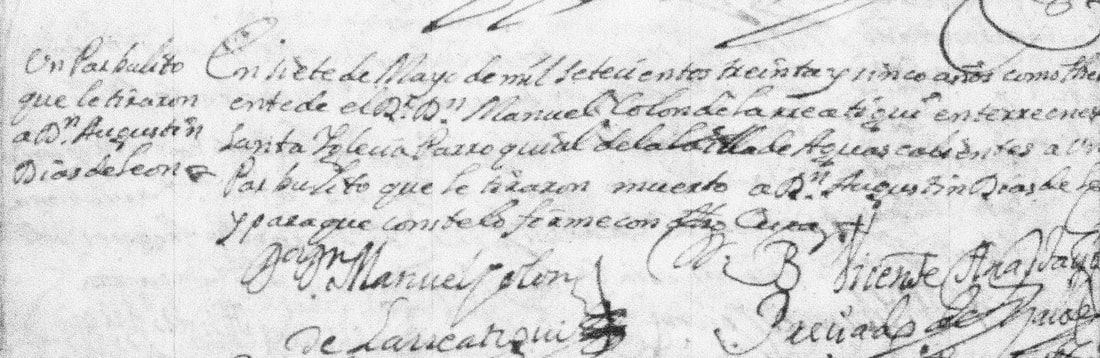

This story is a work of fiction based on historically documented events. All individuals with surnames, including their children, were real people; those without surnames are fictional.

In Mexico tens of thousands of residents, Indians, mestizos and españoles alike, died from intermittent plagues, smallpox, chickenpox, mumps and measles. At times there were so many deaths that the priests were too overwhelmed to comply with church regulations as to the proper listing of entries in the death records, able to note only the date of death and the names, if known, of victims who were interred on that date.

Don Augustín Diaz-De Leon’s child, Pantaleón, died in December 1747, eight months after the death of his father. Pantaleón was three years old. The youngest child, Augustín Miguel Estanislao, was born two weeks after his father’s death, on 11 May 1747. He survived into adulthood, eventually settling in Sierra de Pinos, Zacatecas, where he and Thadea Josepha Gertrudis Muñoz Tiscareño married.

Don Augustín’s widow, doña Maria Antonia Fernandez de Palos Ruiz de Escamilla and el alcalde mayor don Fernando Manuel Monrroy y Carrillo, (witness to the death of don Augustín as well as the executor of his estate) in September 1749 were granted a dispensation to marry. Don Fernando was a widower; his first wife was doña Juana Salvadora Jimenez.

Don Augustín’s father, el alférez (subaltern) don Visente Xabier Diaz-De Leon, was at this time the owner of the Hacienda de Peñuelas. Following the death of his first wife, doña Catharina Acosta, he married and raised another family with his second wife doña María Dolores Medina. Upon his death in April 1754 he left money (including 15 gold Castilian ducats) for his intentions, including 100 masses to be offered for the repose of his soul and for his servants, living or dead.

The ex-Hacienda de Peñuelas, still in existence, is one of the oldest haciendas in the Mexican state of Aguascalientes. Established sometime before 1575, Peñuelas predates the foundation of the Villa of Aguascalientes itself. This hacienda consisted of several self-supporting plantation-like communities staffed and farmed by resident Indians and slaves.

The Cathedral Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, originally known as San Ysidro Labrador, was initiated in 1704 and completed in 1738 by don Manuel Colón de Larreátegui, head of the Mitra de Guadalajara. Its northern bell tower was completed in 1764, the southern bell tower not until 1946.

Sources

All birth and death documents cited are from the following:

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints:

FamilySearch.com and other films on line.

The entry cited re the infant, the parbulito of this story, is from:

Mexico Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, Catholic Church Records

Parroquia del Sagrario, Asunción de Maria

Defunciones 1708-1735, 1736-1748

El Parbulito: Image 530 [Libro quatro de Entierros]

Montejano Hilton, Maria de la Luz:

Sagrada Mitra de Guadalajara, Antiguo Obispado de la Nueva Galicia, 1999

Rojas, Beatriz, et al:

Breve historia de Aguascalientes, 1994

Topete del Valle, Alexandro:

Aguascalientes: Guia para visitar la Ciudad y el Estado, 1973

Vázquez y Rodríguez de Frias, José Luis:

Genealogía de Nochistlán Antiguo Reino de la Nueva Galicia en el Siglo XVII según sus Archivos Parroquiales, 2001

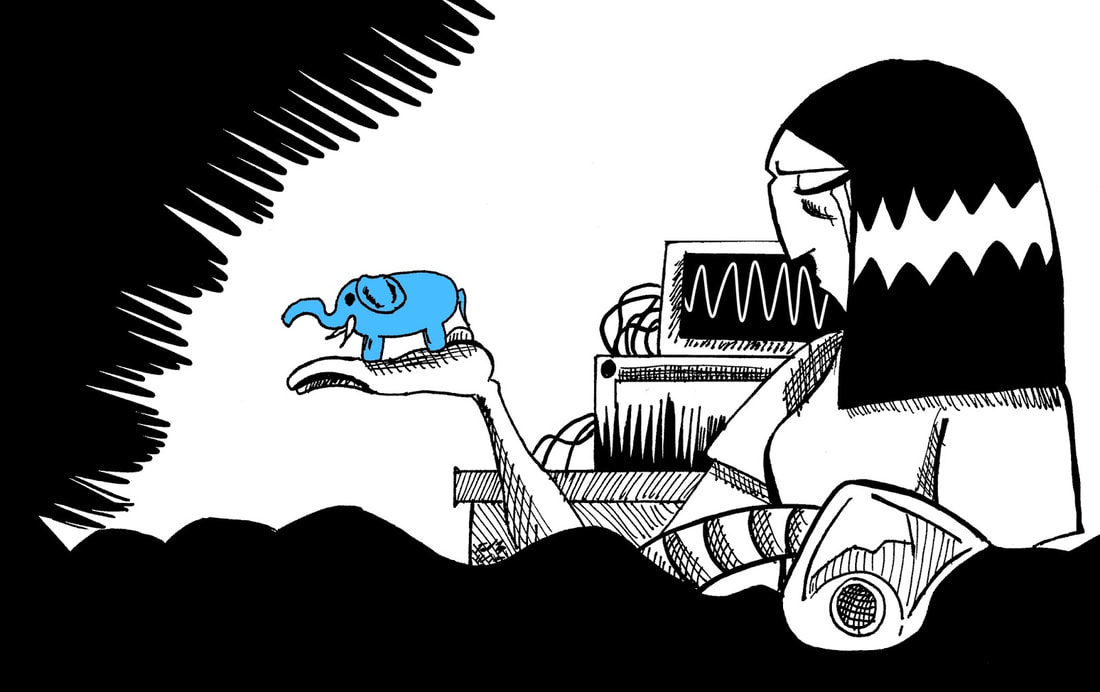

Death and Elephants

By Cristina M. Luna

Sitting in the hospital room, Elena thought much about her own life as she watched her mother’s life dwindle to its end. She thought about the miles upon miles she had traveled in her 34 years of life; the magnificent sites of the world she had seen and never bothered to memorialize through photographs or journals; the love affairs she had felt and lost; the face that age had morphed in the mirror; every momentous and minute memory that made her who she was. All of it seemed random and aimless to Elena now, circumstances haphazardly pushing and pulling her along the tightrope of life, of her life that she could only fully know herself. Her memories would die with her, imparted to no one. She then understood that her mother possessed a life, too, intimate only to herself that Elena would never know, and its only remnant would be a collection of glass and porcelain elephants.

Elena’s heart began to quicken with panic. Her mother would be gone. The permanency of death felt real and unbearably near. Some small part of her, from long ago, believed that her mother could never leave. The enveloping presence of a mother felt forever. She thought of the nine months she didn’t remember inside her mother’s womb when she was, literally, part of her body, absorbing nourishment and space. Once plump and pregnant, her mother’s body was now frail and wilted, its blood cooling and slowing in the veins. Elena remembered plunging her face into her mother’s breast as a child, seeking comfort in her warmth cloaked with a plush turquoise sweatshirt, smelling of fresh detergent. Even as an adult, her mother’s body represented a cradle of respite; Elena’s mascara-mixed tears stained many shoulders of her mother’s fine sweaters. The body would turn to ash, but Elena found solace in the blood they shared flowing within her.

What does a daughter do without a mother?

Elena knew that when her mother passed, a part of herself would die, too, but she knew she would also gain all of herself because she would be able to sever the artery that bound them together in life. Elena was an ambitious woman. She held two master’s degrees and quickly climbed to top executive management at her company. She understood life as a competition, divided into winners and losers, shepherds and sheep. From the first science fair blue ribbon won at age ten, Elena decided that she was a shepherd and a winner. She had little patience for most people and their complexities. She found them wet and messy like paper-mâché, made up of emotional baggages and idiosyncrasies.

But Elena was a beautiful woman. Cursed with her mother’s thick black hair and alluring dark eyes, a continuum of men pleaded for her affection over the course of her life. If she was honest with herself, she couldn’t find a man’s love worthy of commitment because a man’s love is like a knife that cuts you swiftly and deeply in the beginning, but fades and dulls over time. Her mother’s love, however, was constant and continuous, omnipresent like her own heartbeat. As such, Elena found comfort in her isolation from others.

Despite this semblance of independence, Elena often felt like her mother’s eternal child. She never disobeyed, sitting still, like a doll, for hours in her frilly dresses and neat braids when told to do so as a child. She spoke to her mother daily, frightened to explore the uncertainty of life without her mother’s counsel. Should I wear this dress or that skirt? How do I fry an egg? Do you know what this rash is on my arm? Should I ask for the promotion or should I wait? Is he right for me?

She was an overgrown, clumsy little girl in women’s clothing who phoned her mother after any minor stress, seeking comfort in her caretaker for reassurance. Maternal authority demanded that life would be all right. Her mother’s death would kill this coddled child who had always belonged to someone, leaving Elena as a fragmented adult who belonged to no one.

But the elephants would belong to her. This blue one, here, she had singled out from the dozens on display in her mother’s curio cabinet. She had impulsively grabbed it and slipped it in her coat pocket on her way to the hospital. She thought it pretty, the way it looked like a China plate rolled up into the shape of an elephant, the way the blue faded into white down the trunk, and the thin, delicate navy lines that intertwined along the spine.

She would always wonder about the stories behind each of her mother’s elephants, but she knew this one had been a gift from her father. He brought it home from one of his trips overseas. Elena remembered being a young girl and watching her mother carefully open a white box to reveal the dainty blue figurine. Her parents embraced and kissed each other affectionately before her father placed it in the cabinet where it would remain all those years.

Elena and her father had got along well, never particularly close, but now he seemed a stranger. Now all fathers became strange to Elena: male ingredients that facilitated the bond between mother and daughter. He was a good man, a good husband and father, dutiful and present. He provided for their family of five, working eight hours in an office downtown and taking occasional international trips to earn a comfortable salary that afforded more than enough food, shelter, clothing, advanced education, and so on for Elena and her two sisters. Elena found him a pleasant man, never irritable and always in good humor. Her mother loved him passionately, revealing juicy morsels of their early years together to Elena: his poetic love letters and professions, the way his deep blue eyes stared into her soul, his persistence in courting her at nineteen, and most shockingly, his appetite as a lover. This person her mother described was foreign to Elena. With the exception of his thick eyebrows and high cheekbones in her own face, she couldn’t discern him from any other male acquaintance. She didn’t know him, not like she knew her mother who never worked, constantly vulnerable to the emotional disposal of her daughters.

Elena’s father didn’t know her and he would never understand the intimate knowledge a mother imparts to her daughter on the experiences of being female and how to navigate its complicated limitations—its mess of empowerment and skincare routines, ironing the kinks in your hair and choosing the right man, self respect and pap smears, careers and hormones that made you want to burst, high heels and higher education—it was all very confusing. No, he couldn’t understand. In the end, Elena would be left alone with her father—they both would be left alone—with their respective gaping wounds of loss, bathing in the uncomfortable quiet between them.

But at least she would have this elephant. Still holding the object, Elena rested her head on the bed beside her mother. Everyone would soon arrive to crowd the hospital room with more flowers and cards, a strange ritual for an impending death.

She then placed the elephant on the bed, facing her, so she could explore its tiny painted features. It conjured images of her mother’s gleeful smile when she received it, the purple terry-cloth robe and dingy white slippers she wore that morning, her thick glasses and disheveled black ringlets of hair; the minivan she drove when she picked her and her sisters up from school; her melodious laugh; her long, dainty fingers; her stubbornness; her warm embraces; her calming voice over the telephone during college; how she prepared three tupperwares containing the exact same number of pear slices for preschool to ensure equality among sisters. Elena imagined her mother at nineteen with her black curls, disco-era dresses, and gap-tooth smile, exuding sex, depth and levity—a rare, beautiful combination that allured her father; their honeymoon in Paris; their wedding in Mexico; and her mother’s beginnings as the only curly-haired Cuban girl in Massachusetts.

Soon everything would be gone, her mother’s life and body crumbled into nothing. But somehow her mother would remain real in the elephant. All the other elephants were mysteries but this one--this one—she knew. With the elephant, Elena could know her mother if she didn’t know anything else at all. Elena then began to cry.

Suddenly, she heard a knock at the door. She quickly wiped the tears from her face, took a deep breath, and placed the elephant into her coat pocket. She opened the door and greeted her father. Elena welcomed him into the room and they both returned to the hospital bed, sitting on either side. They struggled to make conversation. Elena clutched the elephant in her pocket as they sat in silence, and waited.

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

April 2024

March 2024

November 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

December 2021

November 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

December 2020

September 2020

July 2020

November 2019

September 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

February 2010

Categories

All

Archive

Aztec

Aztlan

Barrio

Bilingualism

Borderlands

Boricua / Puerto Rican

Brujas

California

Chicanismo

Chicano/a/x

ChupaCabra

Colombian

Colonialism

Contest

Contest Winners

Crime

Cuba

Cuban American

Cuento

Cultura

Culture

Curanderismo

Death

Detective Novel

Día De Muertos

Dominican

Ebooks

El Salvador

Español

Español & English

Excerpt

Extra Fiction

Extra Fiction Contest

Fable

Family

Fantasy

Farmworkers

Fiction

First Publication

Flash Fiction

Genre

Guatemalan American

Hispano

Historical Fiction

History

Horror

Human Rights

Humor

Immigration

Indigenous

Inglespañol

Joaquin Murrieta

La Frontera

La Llorona

Latino Scifi

Los Angeles

Magical Realism

Mature

Mexican American

Mexico

Migration

Music

Mystery

Mythology

New Mexico

New Mexico History

Nicaraguan American

Novel

Novel In Progress

Novella

Penitentes

Peruvian American

Pets

Puerto Rico

Racism

Religion

Review

Romance

Romantico

Scifi

Sci Fi

Serial

Short Story

Southwest

Tainofuturism

Texas

Tommy Villalobos

Trauma

Women

Writing

Young Writers

Zoot Suits

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed