|

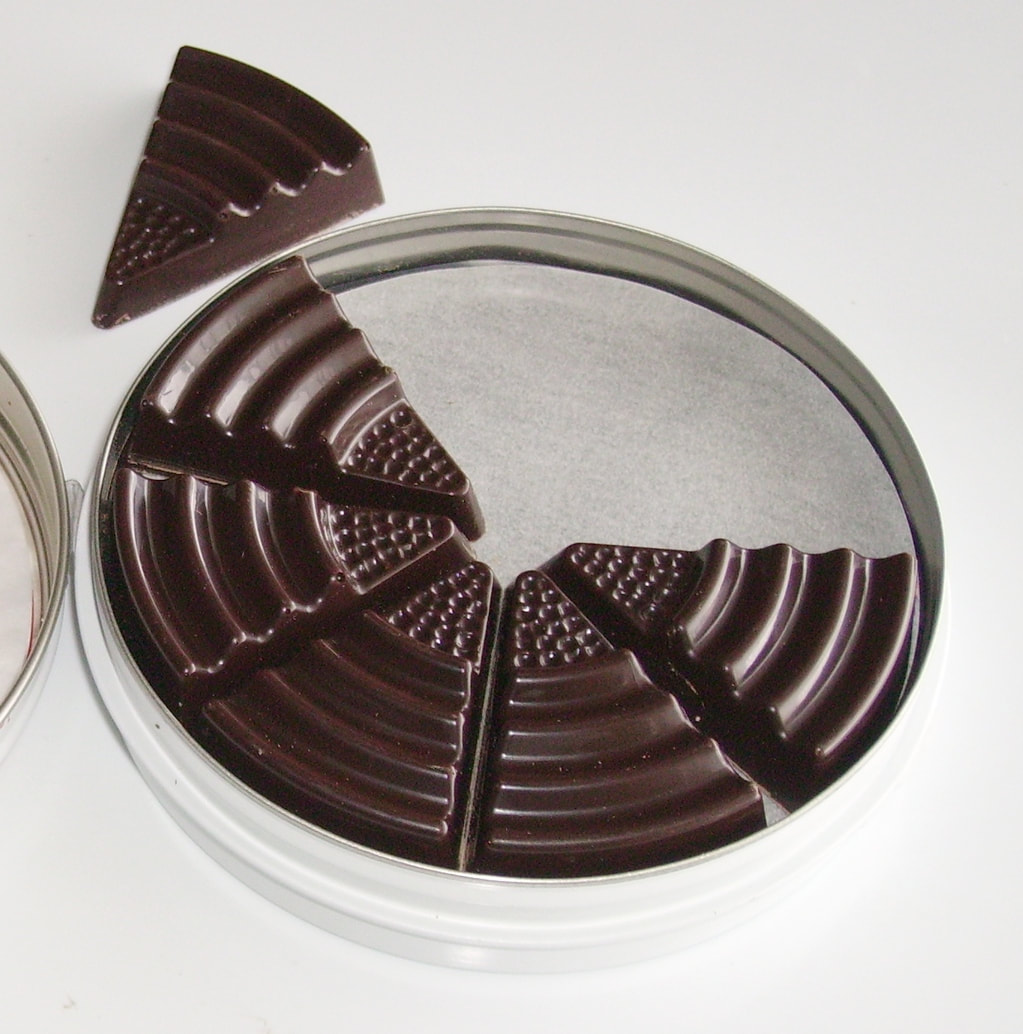

Rinconcito is a special little corner in Somos en escrito for short writings: a single poem, a short story, a memoir, flash fiction, and the like.  Pictured is an open cannister of Scho-Ka-Kola, a caffeinated chocolate produced in Germany starting around 1935 and distributed to many German soldiers during World War II. The protagonist of “Out of Range” recalls widespread starvation in the years following the Spanish Civil War, coinciding with World War II, and a fortuitous encounter with Nazi chocolate. Out of Rangeby Olga Vilella It happened sin darse cuenta apenas. One minute, Josefina Corrada was the exceptional mujer she had always been. A responsible professional. Puntal of the eight o'clock Mass de San Aloishús, even in the worst snowstorm in February. A mother who never disappointed. And the next day, she consigned everybody to hell. “Se me van a hacer puñetas, todos. Y el que me esconda las llaves, me va a oír.” Which is how she came to be waiting for Dr. Haddad, that day. Maybe she should send la familia that funny meme of the cat. Pa’l carajo…a mí nadie me manda. Even Joey, the only among her relatives she could stand these days. But el guaifi seemed to be down. Certainly not to Josie, there was no reasoning with Josie lately. When Josefina thought of her eldest, she had to ask los cielos what sin was she paying for in this life, to have been saddled with such an ingrate of a daughter. Who never called, unless she needed something. Trite, trite, and verging on the caricature, but oh-so-true. A flash of memory sparked in Josefina's mind. She blinked then, assaulted by a draught of icy air and un recuerdo. The pinkie finger in Josie’s left hand, curved slightly inward. The dedo that was a replica of her own. And then she closed the screen pa'quick. No thinking of la Josie. La que me va a armar cuándo se entere. Swipe screen left. Not for anything Josefina was the only one among her friends that Twittered and Instagrammed and Facebooked and TikToked. A brief smile lifted the corner of her perfectly drawn mouth!--Cherris-in-de-esnow de Reblon—with the next image popping up in her head. A circle of silvery heads, jostling around, whenever she showed las amigas how to get on? in?—maldito inglés—social media. Yet again. A small whoosh brought her back to her surroundings. Another blast of frigid air fell on her shoulders from above, like a shower at Varadero Beach Club, on a morning in August. Dios mío, ese aire acondicionado me va a matar de pulmonía. Y esta camilla. A little face, all eyes, peered then from around the curtain of the cubicle. An orangey tube—¡cómo el presidente!—was poised firmly between his lips and a bag dangled from a grubby paw. ¡Un Chito! Food from the gods. Now forbidden by Josie. The sight made her stomach rumble, not for the first time. Josefina tried her nicest smile. Kids usually responded to her abuela charm, but this one was not parting with one curly bit. El niñito left quickly, but the curtain of the cubicle had parted long enough for Mrs. Cou-rra-dah to catch a glimpse of a group in scrubs planted around the nurses’ station. Call me “mom” one more time, anda. See what’s going to happen to you, mija. Will you look at the size of those culos? People are really unattractive these days. “Body shaming, grandma.” “Don’t call her china, grandma, she’s Korean.” The list of her many social sins clacked like dominoes in her memory. Swipe definitely left. But Joey’s gently reproachful face, a caramel Mater Admirablilis, refused to budge, once invoked. “Grandma, be nice. I love you, but be nice. Te quiero mucho,” repeated to signal no bad intent, pronounced in that cute gringuita accent of hers. Joey, tan bella, mi niña. Joey qué no salió a su mamá, that’s for sure. “If those people are Italian, I’m china. Coreana,” Josefina spurted out loud, almost choking, on a breathy yelp. Look at the time, caballero. Deja, que estos van a trinar cuando yo termine con el presidente del hospital. ¡A mí! Qué me hagan esperar a mí, Josefina Corrada, la primera doctora hispana de Jersi Sity. But the memory of her granddaughter’s brown eyes still hovered, stubbornly, before her. It was getting late. And Josefina was so tired. And more shook up than she had thought when the car stopped spinning. Tired, hungry, in need of reviving. “Latte with an extra shot,” she heard Joey order in that papery hoarse voice of hers. Even Joey, even her. “Un café con leche, mijo. Cargadito.” These days, saying those words, en español, felt like an act of resistance. En español, like it or not. Café con leche. Y tu MAGA que te la metes por dónde no te da el sol. Besides, calling out for a café con leche at el Estarboc also conveyed, loudly she hoped, what she thought of people willing to pay más de cinco pesos for a latte. Café con leche, guanajos. “Well, dear heart. It is a fallen world,” as Catalina always repeated, while dusting her bolster of a chest. She knew las niñas would worry about her when she didn’t show up. But she was also sure they went ahead and ate. At this point in their lives, not one of her friends was going to delay ordering lunch because one of them didn’t show up. They would never eat. Maldita vejez. ¿Quién te prepara para esto? ¡Nadie! As if there were any medical textbooks that could prepare you for the indignities of old age. The carefully calibrated contempt in the voice of los jóvenes at the cellphone store. The looks of disdain when you don't put away your wallet fast enough. As if they were never getting old. As if. As if. That movie with la rubita de Beberli Jills. How they had laughed, she and Joey, escapadas, both of them. “No PG-13 movies for her until she's old enough, mom.” As if Joey didn't hear worse every day in school, so guanaja. I wonder what's taking Dr. Haddad so long. Had she been in her right mind, she would have refused the ride to the ER. What had she done instead? Let them wheel her, in while making un chistesito. And not even a good one. “What happened to la ambulancia de los guapitos?” At least, one of them—dominicano by the looks of him—had laughed. “Lady, that's the next crew. And they won't be here for a while.” “You think you’re really funny, don't you, abuela?” As a matter of fact, yes, she thought she was pretty funny. Even Joey turned on her these days. For nearly seventy years, she had been a good girl. Not anymore. ¡Se acabó! She was now primed for war. Ready a dar guerra like the warrior she had once been. The buena hija who told her father she was going to medical school during that lunch, so, so many years ago. Dios mío, cómo se puso, loco furioso. Contrarian, contrarian, cómo eres, Enrique used to say. The faces from other days of conflict crowded the small space around the gurney. Her father hitting the lunch table with a fist, the afternoon she told him Enrique was coming to talk to him. Certainly, she was marrying him. And she was moving to La Habana con él. Y mamá, llora que llora. Why couldn't she understand? She left México con papá. Igualitica, igualitica que tu padre, Enrique used to say. David Juño, cerrado cómo un puño. The man who refused to ever go to el paseo once the war was finally over. “Cara al sol/con la camisa abieeeertaaaaa.” Somebody would intone the anthem of the Nacionales in the middle of la Alameda and the crowd would pause, as if paralyzed. Shifty eyes taking note. Black shirts and a sea of raised hands, saluting. An arm lifted, stiff like a gravestone, like el Caudillo's, meeting Hitler in Hendaya. Not that don David had any use for the other side. Not after what they had written on the doors of the apartment building in Madrid. “Muerte al dueño de este edificio.” And Lelia's daughter dying during the siege. She died of a pneumonia, they said. We knew it was hunger. “Recuerda, Pepiña. En este pared, unos españoles asesinaron a otros españoles.” Y el hambre por todos lados. As many maids as any house would want, to be had for a pair of alpargatas and their keep, during those years of darkness. Niñas, niñas todas. And then the years of that other war. Grey uniforms, all over the city. The whole of the province, all of Galicia, was overrun by them. On leave from the German submarine base in El Ferrol, la tata Rosalía would whisper, moving away from their Nordic raptor eyes. And Amelia, all blonde trenzas and blue eyes, pretending she was a refugee. “Kinder, kinder, schokolade.” After all these years, those words remained fresh in her memory, as bittersweet as the taste of that chocolate long gone. Better make sure next time Joey took her to el Cosco she bought enough garbanzos. And a big bag of those small Esniqers. “My dear colleague, what is this I hear about you still driving?” El doctorcito Haddad. Here we go....  A native of Río Piedras, Puerto Rico, Olga Vilella is currently at work revising Los que llegaron, a historical novel based on the unsuccessful attack by the English to San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1797, a work that seeks to upend Caribbean notions of race, religion, and ethnicity.

0 Comments

To Grow Young Old Simeón’s right hand was permanently clawed. His curled, yellowing nails converged towards each other in a longing gesture, as if he were trying to grasp the last strands of something long gone. Sometimes Vanessa wondered why such a particular fate had infested Old Simeón’s phalanges. She hypothesized that the clawing probably happened gradually, like the shrinking of a flower’s petals as water breathes itself out. But another, much more grim possibility had come to her one night as she was falling asleep on her unshared bunk bed. She envisioned that fatal agglomeration of blood obstructing Old Simeón’s left brain, and his extremities instantly recoiling at the evaporation of half a life. Every morning, when Vanessa took it upon herself to massage Old Simeón’s wrinkly fingers, she felt a piercing worry that her body would betray her in that same way. She thought of all the inexcusable curses she had directed at her limited limbs when her feet couldn’t bear two days of walking after crossing the Venezuelan border. At the time, driven by impatience, she had collapsed on the side of a jungle-ridden highway, where only blades of dried grass had pierced her back into consciousness. She had asked God why none of the passing cars acknowledged her stretched out thumb, and jerking her damp sneakers out of her feet, she asked why her throbbing toes wouldn’t allow her to reach a couple kilometers further, where maybe she would find a hospitable town. After many years, Vanessa found herself able to take pride in some things again. Small things. For instance, she claimed all credit for the slight tremble of Old Simeón’s fingers whenever his wife took his stiff hand in between hers. She took pride now, in his ability to juggle up a pair of dice and throw them on a parqués board, with the help of his left hand, which was spared by some impossible bifurcation of the brain’s connections. The dice clinked against the glass board and showed a pair of six dots protruding from the white cubes. “How much is that, Don Simeón?” Vanessa said, lifting his arm from the table to prevent him from accidentally pushing the pawn-shaped pieces off. Old Simeón let out a brief growl and stared at the blank air behind Vanessa’s curls. “Twelve,” she answered herself. She took Old Simeón’s red pawn and hopped through the boxed trail. “One, two, three, four…” Vanessa then took advantage of her turn and threw the dice on the board. They spun around until the odds settled for two and four dots. A prolonged sigh coming from the other side of the room stopped Vanessa from killing one of Old Simeón’s red pieces. Doña Rosario’s glasses reflected the blue light coming from a box-shaped TV. The bulging screen showed footage of flooded streets and fallen palm trees, brown heads peering out of hills of roof tiles and window frames. “Not one house is still standing, can you believe it?” Doña Rosario said, noticing Vanessa’s shared interest in the news report on hurricane Iota. “The island will need a full reconstruction, they say,” Vanessa had been following the case from a blue radio that she kept in her room. The numbers were most astonishing. 1600 families, 98% of infrastructure. Still, she found it hard to sympathize with the victims. She couldn’t help but think that her people had probably gone through worse, just nobody had bothered to quantify it. “Providence Island is a beautiful place,” Doña Rosario said, in her unusually high-pitched tone. “You know where my last name comes from? Abraham Robinson, my grandfather, immigrated from Britain to Providence Island.” The way Doña Rosario pronounced every one of those words with utmost pride kept Vanessa from coming up with any reasonable response. Doña Rosario had a way of talking. When she had given Vanessa the keys to her recondite bedroom, Doña Rosario made it clear that she came from a long tradition of landowners who knew how to manage helpers in the household. “Your nursing title does not make a difference,” Doña Rosario had said. “I still expect obedience and respect in your care for my husband.” Throughout the many months that Vanessa had worked for Doña Rosario, she had come to realize that behind her harsh words stood her unconditional love for Old Simeón, but also her self-remorse for having married a man 15 years older in age. The old man’s life was coming to an end, and he was swallowing Doña Rosario’s own life along the way. From beneath the open windows, not only moonlight leaked through the iron bars, but also the flickering lights coming from a neighbor’s balcony. Behind linen curtains, dark silhouettes danced to the congas in Rodolfo Aicardi’s La Colegiala. It was only late November, but the people of Acacías were already playing New Year songs over indecently loud speakers. At least in that respect, Acacías wasn’t all that different from back home, Vanessa thought. She had also noticed they had the same tradition of making a dummy filled with gunpowder and setting it on fire just as the clock struck midnight. Old Simeón and Doña Rosario never engaged in such activities though, because no matter what day of the year it was, they always went to sleep promptly at 8 p.m. Old Simeón tapped Vanessa’s shoulder with a poignancy that disoriented her. He pointed at the color-lit balcony. “They must be having a party, Don Simeón,” Vanessa said, assuming that was the information that Old Simeón was requesting. “And you?” Old Simeón responded, his words as clear as they ever got, carrying the rasp of an underused voice. Vanessa was not entirely sure what Old Simeón meant. Perhaps he found it strange that someone of her age was playing parqués with an old man instead of curling her hips to tropical beats, or he was wondering why the neighbors had not invited her. Vanessa smiled at the thought of these possibilities. “None of us are supposed to be partying,” she said. “There’s a very bad virus out there, so we have to stay home.” In some corner of the world inside Old Simeón’s mind, he knew it was the pandemic that had insulated his days so much. But Vanessa was not aware of this. She was rather excusing her situation, considering that maybe once it was all over, things would be different for her. “You heard that, Simeón?” Doña Rosario said, projecting her voice to make herself audible to Old Simeón’s almost deaf ears. “Our last years of life, at home.” By the time the news broadcast was over, Old Simeón had already fallen asleep on his wheelchair. His nightly routine consisted of Vanessa and Doña Rosario collaborating to strip him of his clothes and tie his diaper around his waist. The diaper was rather an ornament, since Old Simeón would wet his bed sheets every night, and every day Doña Rosario would replace them with a new set. *** Vanessa had little to complain about. Her salary, although less than legal minimum wage, was enough for her personal expenses. Since Doña Rosario and Old Simeón provided her with a place to sleep and three meals a day, she also had enough money to send to her family in Venezuela every month. She planned to keep saving up to bring her mother with her too, away from a dictator’s injustices and a husband’s infidelities. There was a catch to her living arrangement, though. Some days, Doña Rosario would wake her up particularly early and ask her to make breakfast. Vanessa could tell that Doña Rosario did not like her cooking, as she always complained that she put too much salt on the eggs, or not enough cheese in the arepas. Therefore, Doña Rosario’s request took place only when strictly essential, like when she had to go get fresh milk at the plaza on Saturday morning, or when she attended early morning mass. This time, Doña Rosario had woken her up with a phone pressed against her ear. Doña Rosario had learned to pick up calls, but never to make them, so when some relative or friend called her, she made sure to catch up with them for at least an hour. However, when Doña Rosario had tapped on Vanessa’s door, her furrowed eyebrows and trembling lips suggested that this was not one of her usual bubbly phone calls. Instead, she was quiet, while a female voice at the other end of the line spoke in mechanical shudders. As Vanessa walked up to the kitchen, Doña Rosario took a seat on the adjacent dining table. Old Simeón, his eyelids still struggling to stay open, sat on his wheelchair in front of the TV at the end of the room. In between the whisking of eggs and the patting of arepa dough, Vanessa managed to catch some slivers of Doña Rosario’s conversation—“What do you mean?”, “Hmph,” “God Bless,” “Why don’t you come over?” Judging by Doña Rosario’s choice of the pronoun Tú instead of Usted, the person at the other end of the line could only be her daughter, Nadia. She was Old Simeón’s and Doña Rosario’s only daughter, even after 60 years of marriage. Less often than Doña Rosario would’ve liked, she took her Chevrolet Swift down the narrow road between Villavicencio and Acacías to visit them. When Old Simeón’s pension fell short, her teaching paychecks would pay for the house bills, as well as Old Simeón’s medicine. Vanessa knew rather little about Nadia, but what she’d heard pushed her to garner utmost respect. She heard that Nadia had been in the house when Old Simeón had gotten his first thrombosis attack. He’d fallen on the floor, shaking and salivating as if being possessed by an evil spirit. Doña Rosario had stood frozen, covering her eyes away from the sight of her convulsing husband. But Nadia had been the one to pick her father up from the floor and place him on a chair, before calling every relative in town in search for an after-hours doctor. She was the reason he was still alive. Once Vanessa was done helping Old Simeón eat his breakfast, Doña Rosario gestured for her to sit at the dining table. “Nadia is coming later this afternoon,” Doña Rosario said, but she wouldn’t meet Vanessa’s gaze. “Vanessa, I need your full discretion on what I am about to tell you.” Before making breakfast, Vanessa had tied her black curls into the shape of an onion. The pull of the low-hanging bun tugged at her hair as she nodded. “Simeón’s brother Alberto passed away last night,” Doña Rosario said in a soft voice. “He caught that damned virus.” Even though Vanessa had never heard of said brother, she made sure to state her condolences as politely as possible. “You know he can’t know, right?” Doña Rosario briefly glanced at Old Simeón. “He’s not in the proper state to hear this.” In spite of the prolonged coexistence of the three members of that household, Vanessa was the only one who made an effort to converse with Old Simeón. Sometime after Old Simeón had become speech impaired, Doña Rosario had lost all her patience, seeing that her only companion could no longer reciprocate her interactions. Now she limited herself to short words, and the warmth of touch. Vanessa, instead, would talk to him about the warm weather, the dogs barking outside; anything that crossed her mind. His answers consisted of low groans, unintelligible mumblings, and the occasional phrase that one could judge as either gibberish, or the enigmatic findings of a mind sorting through an extensive past. Vanessa liked to think it was the latter. *** Whenever Vanessa heard Nadia and Doña Rosario talking to each other, she couldn’t help but wonder how it was possible that she sounded so different from them. She was puzzled by their ability to give every syllable a distinct tonality. They seemed to have every unit of sound recorded in a dictionary, that they would parse through in every uttering. They took no shortcuts, unlike Vanessa, who could not find the time to bring her tongue to the roof of her mouth swiftly enough to whistle her words—her ‘s’ sounds would descend into brief sighs. However, she had learned to minimize her vocal sloth during her time in Acacías. Doña Rosario had told her that not everyone in that town would be as kind to her people as she was. Nadia and Doña Rosario sat on the dining table, their short coffee cups steaming next to their fidgeting hands. Vanessa glanced at them intermittently through the windows, as she pushed Old Simeón’s wheelchair around the house. She could tell that at one point Old Simeón had made a habit of walking around the house, because he seemed to have picked favorite spots to glance at throughout the perimeter. At the back of the house, he liked to look at one of the columns that held up the clay roof where the white paint had peeled off in a shape resembling a trail of mucus left by a slug. At the right side of the house, the edge that faced a living fence which separated their neighbor’s house from theirs, he liked to look at a patch of red ground where grass had refused to grow. From the turning of the soil, Vanessa could only assume that a tree had once stood there, and she imagined it to be as high as the neighbor’s balcony. At the front of the house, Old Simeón usually stared at the plastic bowls filled with brown cat food that sat next to the front door. They owned three cats who spent more time on the streets than at home and would only let themselves be petted by Old Simeón. Today, there were no cats to be seen, and Old Simeón was instead looking through the window, towards where Nadia and Doña Rosario were sitting. Vanessa could tell by the disparity between Nadia’s age and the number of wrinkles that crisped around her eyes that she had a tough disposition. Her downturned lips were unphased by both the taste of black coffee and Doña Rosario’s slow tears. “You must’ve been a really good man, Don Simeón,” Vanessa said, pushing the wheelchair into motion away from the window. “You raised a very strong daughter.” The feeble white hairs on Old Simeón’s scalp trembled with the gush of the wind. Otherwise, he remained motionless to Vanessa’s words. She continued. “I think that’s what matters. Knowing that you’re leaving this world having created something good,” Vanessa said. “Is that more or less right, Don Simeón?” This time, Old Simeón let out a deep mumble and twitched his head in a manner that could’ve been a nod, or an attempt to shake away a mosquito’s itch. Vanessa noticed that Old Simeón seemed particularly light on the wheelchair today. One of the reasons why Doña Rosario had hired her was because of her big arms and thighs. She could manage the weight of pushing Old Simeón’s chair down Acacías’ unpaved roads and steep bridges. “I’ve got a lot to learn from you, believe it or not,” Vanessa continued, ignorant to Old Simeón’s droopy eyelids. “I’ve been thinking about what comes next. For me, you know. I’ve been thinking that maybe after all of this virus thing is over, I could move to the city. Work for a retirement home, maybe? And meet some people. Build something of my own. Wouldn’t that be good?” Old Simeón’s clawed hand suddenly stiffened around the wheelchair’s armrest. He sat with his spine straightened out, fighting against a decade-old hunch. When the clock struck 2 p.m., the designated time for Old Simeón’s daily stroll was over. Doña Rosario and Nadia were still sitting at the dining table, but their urgent whispering had stopped and transformed into vociferous complaining about why the chicken delivery had not arrived yet. Doña Rosario instructed Vanessa to heat up some of the leftover rice from the day before, so she wheeled Old Simeón’s chair to the dining table and secured the brakes before walking up to the kitchen. She had just struck a match alight when the squeak of sliding wooden chairs called her back into the dining room. Back there, Old Simeón was still sitting in his wheelchair, and Nadia and Doña Rosario were kneeling at each of his sides. His expression was twisted so that every one of the creases that time had encroached on his skin were sunken in, and dense tears were running down the labyrinth of his face. “You told him.” Doña Rosario said, turning towards Vanessa’s newcomer presence. She took a step back and kneeled to Doña Rosario’s height. “I swear I didn’t. It must be something else that’s troubling him,” Vanessa said, the sighs in her speech as heavy as ever. Doña Rosario stood up and the folds on her long skirt swirled wind at Vanessa’s face. “He fought in the military, for God’s sake. He doesn’t just cry.” Vanessa continued to excuse herself while she picked herself up from her kneeling trance. Behind Doña Rosario, Nadia took a pack of Kleenex out of her bag and handed it to Old Simeón. He folded his once clawed hand around the tissue and groaned into the white cotton. But all Vanessa could notice was the tightness of the tendons on Doña Rosario’s neck, which pulled her entire face into a murderous stare. “You Venezuelans can’t keep your mouth shut,” she said. That night, Nadia left without saying goodbye to Vanessa, but she found a funeral invitation wrapped in violet ribbons sitting on her lower bunk bed. After writing down an event reminder on her phone, Vanessa turned on her blue radio and pulled out the long antenna to tune in to the nighttime news broadcast. She fell asleep to the sound of a clinical female voice announcing the hopes for a successful vaccine against COVID-19 in early December.  Laurisa Sastoque is a student of Creative Writing and History at Northwestern University. She was born in Bogotá, Colombia, and currently resides in Evanston, Illinois. Her poetry work has been previously published in Somos en Escrito and the Helicon Literary & Arts Magazine. She is the winner of the Mary Kinzie Prize in Nonfiction for her essay "Contradicting Home; Anecdotes and Aphorisms." She is excited to make her short fiction debut with "To Grow Young," a piece about complicated family dynamics in rural Colombia. In addition to writing and reading, Laurisa likes to spend her time researching Latinx and Latin American history, and taking pictures of her favorite cities. Encontrar una voz en espanglishUn extracto de 9 Cuentos de inmigrantes en los Estados Unidos, una colección de cuentos |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed