|

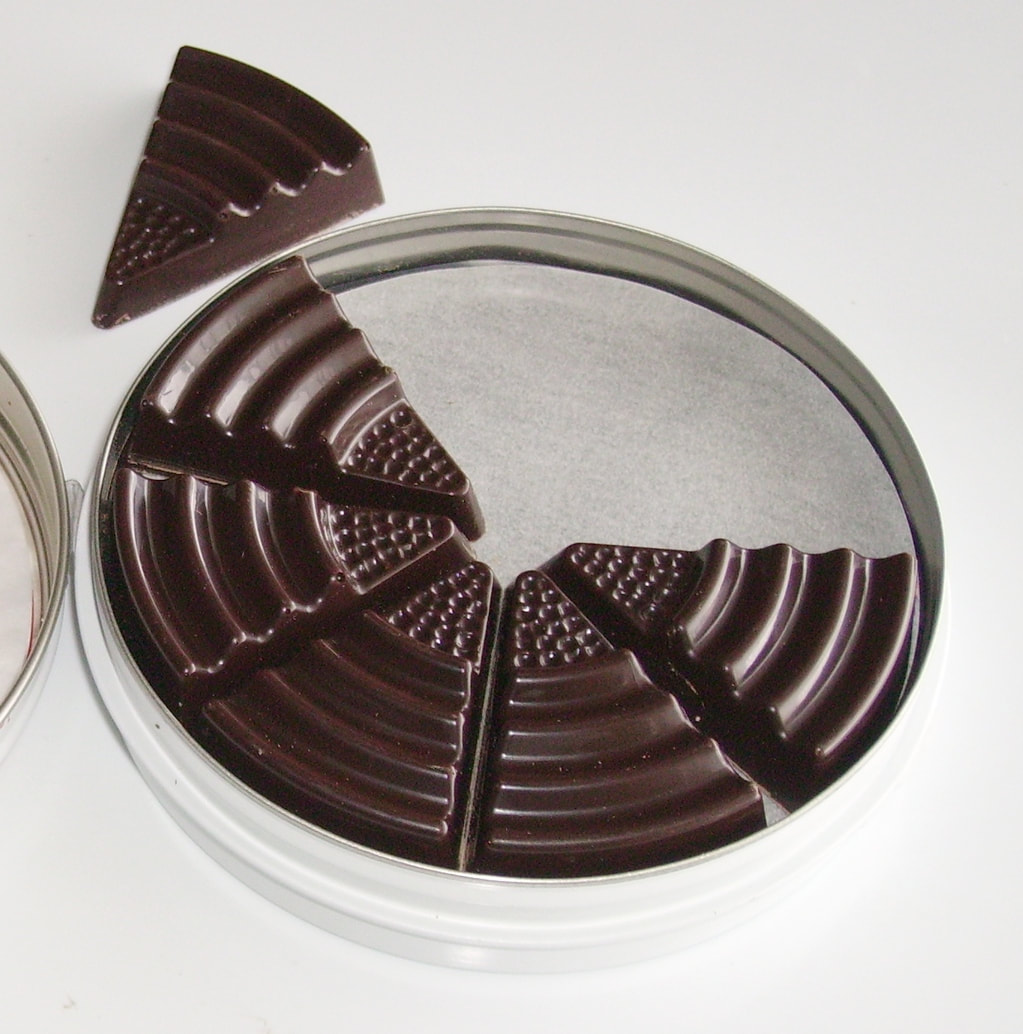

Rinconcito is a special little corner in Somos en escrito for short writings: a single poem, a short story, a memoir, flash fiction, and the like.  Pictured is an open cannister of Scho-Ka-Kola, a caffeinated chocolate produced in Germany starting around 1935 and distributed to many German soldiers during World War II. The protagonist of “Out of Range” recalls widespread starvation in the years following the Spanish Civil War, coinciding with World War II, and a fortuitous encounter with Nazi chocolate. Out of Rangeby Olga Vilella It happened sin darse cuenta apenas. One minute, Josefina Corrada was the exceptional mujer she had always been. A responsible professional. Puntal of the eight o'clock Mass de San Aloishús, even in the worst snowstorm in February. A mother who never disappointed. And the next day, she consigned everybody to hell. “Se me van a hacer puñetas, todos. Y el que me esconda las llaves, me va a oír.” Which is how she came to be waiting for Dr. Haddad, that day. Maybe she should send la familia that funny meme of the cat. Pa’l carajo…a mí nadie me manda. Even Joey, the only among her relatives she could stand these days. But el guaifi seemed to be down. Certainly not to Josie, there was no reasoning with Josie lately. When Josefina thought of her eldest, she had to ask los cielos what sin was she paying for in this life, to have been saddled with such an ingrate of a daughter. Who never called, unless she needed something. Trite, trite, and verging on the caricature, but oh-so-true. A flash of memory sparked in Josefina's mind. She blinked then, assaulted by a draught of icy air and un recuerdo. The pinkie finger in Josie’s left hand, curved slightly inward. The dedo that was a replica of her own. And then she closed the screen pa'quick. No thinking of la Josie. La que me va a armar cuándo se entere. Swipe screen left. Not for anything Josefina was the only one among her friends that Twittered and Instagrammed and Facebooked and TikToked. A brief smile lifted the corner of her perfectly drawn mouth!--Cherris-in-de-esnow de Reblon—with the next image popping up in her head. A circle of silvery heads, jostling around, whenever she showed las amigas how to get on? in?—maldito inglés—social media. Yet again. A small whoosh brought her back to her surroundings. Another blast of frigid air fell on her shoulders from above, like a shower at Varadero Beach Club, on a morning in August. Dios mío, ese aire acondicionado me va a matar de pulmonía. Y esta camilla. A little face, all eyes, peered then from around the curtain of the cubicle. An orangey tube—¡cómo el presidente!—was poised firmly between his lips and a bag dangled from a grubby paw. ¡Un Chito! Food from the gods. Now forbidden by Josie. The sight made her stomach rumble, not for the first time. Josefina tried her nicest smile. Kids usually responded to her abuela charm, but this one was not parting with one curly bit. El niñito left quickly, but the curtain of the cubicle had parted long enough for Mrs. Cou-rra-dah to catch a glimpse of a group in scrubs planted around the nurses’ station. Call me “mom” one more time, anda. See what’s going to happen to you, mija. Will you look at the size of those culos? People are really unattractive these days. “Body shaming, grandma.” “Don’t call her china, grandma, she’s Korean.” The list of her many social sins clacked like dominoes in her memory. Swipe definitely left. But Joey’s gently reproachful face, a caramel Mater Admirablilis, refused to budge, once invoked. “Grandma, be nice. I love you, but be nice. Te quiero mucho,” repeated to signal no bad intent, pronounced in that cute gringuita accent of hers. Joey, tan bella, mi niña. Joey qué no salió a su mamá, that’s for sure. “If those people are Italian, I’m china. Coreana,” Josefina spurted out loud, almost choking, on a breathy yelp. Look at the time, caballero. Deja, que estos van a trinar cuando yo termine con el presidente del hospital. ¡A mí! Qué me hagan esperar a mí, Josefina Corrada, la primera doctora hispana de Jersi Sity. But the memory of her granddaughter’s brown eyes still hovered, stubbornly, before her. It was getting late. And Josefina was so tired. And more shook up than she had thought when the car stopped spinning. Tired, hungry, in need of reviving. “Latte with an extra shot,” she heard Joey order in that papery hoarse voice of hers. Even Joey, even her. “Un café con leche, mijo. Cargadito.” These days, saying those words, en español, felt like an act of resistance. En español, like it or not. Café con leche. Y tu MAGA que te la metes por dónde no te da el sol. Besides, calling out for a café con leche at el Estarboc also conveyed, loudly she hoped, what she thought of people willing to pay más de cinco pesos for a latte. Café con leche, guanajos. “Well, dear heart. It is a fallen world,” as Catalina always repeated, while dusting her bolster of a chest. She knew las niñas would worry about her when she didn’t show up. But she was also sure they went ahead and ate. At this point in their lives, not one of her friends was going to delay ordering lunch because one of them didn’t show up. They would never eat. Maldita vejez. ¿Quién te prepara para esto? ¡Nadie! As if there were any medical textbooks that could prepare you for the indignities of old age. The carefully calibrated contempt in the voice of los jóvenes at the cellphone store. The looks of disdain when you don't put away your wallet fast enough. As if they were never getting old. As if. As if. That movie with la rubita de Beberli Jills. How they had laughed, she and Joey, escapadas, both of them. “No PG-13 movies for her until she's old enough, mom.” As if Joey didn't hear worse every day in school, so guanaja. I wonder what's taking Dr. Haddad so long. Had she been in her right mind, she would have refused the ride to the ER. What had she done instead? Let them wheel her, in while making un chistesito. And not even a good one. “What happened to la ambulancia de los guapitos?” At least, one of them—dominicano by the looks of him—had laughed. “Lady, that's the next crew. And they won't be here for a while.” “You think you’re really funny, don't you, abuela?” As a matter of fact, yes, she thought she was pretty funny. Even Joey turned on her these days. For nearly seventy years, she had been a good girl. Not anymore. ¡Se acabó! She was now primed for war. Ready a dar guerra like the warrior she had once been. The buena hija who told her father she was going to medical school during that lunch, so, so many years ago. Dios mío, cómo se puso, loco furioso. Contrarian, contrarian, cómo eres, Enrique used to say. The faces from other days of conflict crowded the small space around the gurney. Her father hitting the lunch table with a fist, the afternoon she told him Enrique was coming to talk to him. Certainly, she was marrying him. And she was moving to La Habana con él. Y mamá, llora que llora. Why couldn't she understand? She left México con papá. Igualitica, igualitica que tu padre, Enrique used to say. David Juño, cerrado cómo un puño. The man who refused to ever go to el paseo once the war was finally over. “Cara al sol/con la camisa abieeeertaaaaa.” Somebody would intone the anthem of the Nacionales in the middle of la Alameda and the crowd would pause, as if paralyzed. Shifty eyes taking note. Black shirts and a sea of raised hands, saluting. An arm lifted, stiff like a gravestone, like el Caudillo's, meeting Hitler in Hendaya. Not that don David had any use for the other side. Not after what they had written on the doors of the apartment building in Madrid. “Muerte al dueño de este edificio.” And Lelia's daughter dying during the siege. She died of a pneumonia, they said. We knew it was hunger. “Recuerda, Pepiña. En este pared, unos españoles asesinaron a otros españoles.” Y el hambre por todos lados. As many maids as any house would want, to be had for a pair of alpargatas and their keep, during those years of darkness. Niñas, niñas todas. And then the years of that other war. Grey uniforms, all over the city. The whole of the province, all of Galicia, was overrun by them. On leave from the German submarine base in El Ferrol, la tata Rosalía would whisper, moving away from their Nordic raptor eyes. And Amelia, all blonde trenzas and blue eyes, pretending she was a refugee. “Kinder, kinder, schokolade.” After all these years, those words remained fresh in her memory, as bittersweet as the taste of that chocolate long gone. Better make sure next time Joey took her to el Cosco she bought enough garbanzos. And a big bag of those small Esniqers. “My dear colleague, what is this I hear about you still driving?” El doctorcito Haddad. Here we go....  A native of Río Piedras, Puerto Rico, Olga Vilella is currently at work revising Los que llegaron, a historical novel based on the unsuccessful attack by the English to San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1797, a work that seeks to upend Caribbean notions of race, religion, and ethnicity.

0 Comments

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed