Un jardín de claveles blancosPor Alex V. Cruz El chico de boca rosada le mordió los labios mucho antes de conocerlo en persona. Ocurrió en un sueño, pero Lucas no lo comprendió hasta el siguiente día que, mientras caminaba con la boca sabor a sangre coagulada, lo vio andar los pasillos de la universidad Utesa, recinto Moca, como si nada hubiera ocurrido. Lo conoció por sus labios, largos y delgados como orugas de polilla, y por la manera en que caminaba, pecho alto y espalda recta como si llevara la torre Eiffel metida por el culo. Sus ojos las aguas azules del mar mediterráneo, y su pelo carbón carecía la textura característica de pelo malo. Se llamaba Mateo, y Lucas lo supo por las olas de bochinches en la que navegaban las chicas que lo veían caminar por los pasillos ardientes de la pequeña universidad cibaeña. Lucas, con la punta de su lengua, pasó el día jugando con los agujeros que dejaron los dientes de Mateo en el adentro de su boca. Ya no sentía el dolor naufragante de la mañana, pero aún estaba ahogado en el sabor metálico cliché de la sangre. Cuando terminó su día universitario, se acostó en uno de los bancos por el jardín principal de aquella institución, donde podía ver las nubes oscuras contemplar cómo y cuándo arruinarían el día de los jornaleros diarios. “Nos conocemos,” Lucas escuchó a alguien decir, y no tuvo que moverse para saber que era el chico español que traía a todos locos. Sus eses agudamente pronunciadas y el intercambio de la ce por la ze lo delató casi instantáneamente. “No creo,” dijo Lucas, sentándose en el banco y mirándolo a los ojos, porque de que otra manera iba a explicar que lo conoció en un sueño, que todavía lleva el sabor de su boca y sus dientes marcado bajo sus labios. En lo profundo de sus entrañas, en un lugar cerquita al corazón, cuyo latía como locomotora del siglo XIX, llevaba la memoria de la humedad de su piel. “Sabes,” dijo Mateo, “eres muy atractivo…” Lucas perdió el contacto con los ojos de Mateo. Sus cachetes sonrojaron bajo la melanina diluida de su piel. “… para ser dominicano.” Mateo continuó por su camino, el viento jugando con su pelo y sol adorándolo. Lucas, aún sentado en su banco, vio como un chico, quien él conocía de cara, pero no de nombre, caminaba con su mochila a medio hombro, y su camisa ensangrentada en el pecho. La porción inferior de su boca totalmente devorada, y su espalda sudada. “Ese seré yo mañana,” dijo Lucas. Las primeras gotas del diluvio de esa noche se encunaron en el pelo crespo de Lucas, y supo que era hora de echar camino a casa, donde su madre, con sus huesos de osteoporosis, lo estaría esperando con la comida servida en la mesa, y con el orgullo de ver a su hijo universitario plasmado en su cara. *** Se esperaba el tercer huracán de esa temporada, y Lucas se aseguró de llevar en su mochila la sombrilla que no podría usar por los fuertes vientos. También encontró la bufanda olvidada de su primo americano y la envolvió en su cuello bastante veces para cubrir la sangre que caía por la falta de toda su mandíbula y parte de su cuello. No quería ensangrentar el examen de Civilizaciones Mesoamericanas que tenía esa mañana. Ya el maestro se las traía con él y no quería darle más pretexto para que le reprobara la clase. Lucas llegó tarde a clase. El carro público de infinita capacidad que tomó esa mañana se averió a muchas cuadras de la universidad. Entre los fuertes vientos que amenazaban hacer volar esa bufanda teñida de sangre y el agua percusionista, Lucas pasó por el puertón principal sin despertar el guachimán que protegía la universidad para que nadie la atacara en sueños. Los pasillos ya estaban vacíos y solo quedaba el mal olor de almas y cabello mojado. Se encontró con Mateo, nariz perfilada y pelo brilloso, que lo miraba por debajo de sus pestañas. “Quiero más,” él dijo, y fue en ese momento que Lucas reconoció que Mateo lo estaba esperando. La sangre hecha para el sonrojo brotó por la carne desgarrada de donde debía estar la mandíbula, enchumbando aún más la ya pesada bufanda. Lucas desenvolvió la bufanda poco a poco hasta revelar su labio superior y brotes de sangre fresca y coagulada. Mateo se le acercó y, con su lengua larga y puntiaguda, lamió la cara de Lucas por la frente y bajo las sienes hasta encontrar en su cuello un pedazo de piel aún no destripada por sus dientes y empezó a comérselo a mordidas, deleitándose de su piel morena. Una chica, que salió de un salón de clases, gritó y se desmalló al ver tanta pasión entre los chicos. A Lucas no le quedaba nada en el cuello ni en la parte superior de las clavículas más que esa poca carne rosada y obstinada que no quería desprenderse de los huesos blancos. La bufanda ya no podía cubrir su cuello completo y temía que sus compañeros pensara que parecía zombi de una película de terror. Decidió tomar el día libre. De todas maneras ya era muy tarde para tomar el examen de Civilizaciones Mesoamericanas, así que regresó a la parada de carros para ir a casa, pero los choferes, al ver el derroche de sangre por todo su cuerpo, le negaron la entrada y no tuvo mas que irse caminando entre el viento, que soplaba tan fuerte que levantaba los vehículos y los hacia llegar rápido a sus destinos. *** En casa, donde Lucas puso sus libros abiertos en la mesa coja para que secaran, su madre lo esperaba mientras revolvía el sancocho de tres días en la gran paila de aluminio. “Mira la televisión,” dijo ella, apuntando con los labios al televisor que usaba de antena un paraguas para desviar el gotero del techo de zinc. “El ojo llega hoy y va acabar con todo.” Lucas temía que cancelaran las clases. Temía que no iba a poder ver a Mateo. Temía que no iba a sentir sus labios sobre su carne cruda. Esa noche, entre las fuertes ráfagas de viento, la inagotable lluvia, y los macos escabulléndose entre las tablas de madera buscando refugio, Lucas soñó de nuevo con el chico blanco de la escuela. Este le devoró el pecho y el brazo izquierdo dejándolo en huesos y tendones. Lucas despertó, solo su habitación quedaba en pie. El resto de la casa y su madre se los llevó el huracán y nunca fueron encontrados. “Maldición,” dijo Lucas. “Casi no me queda nada que ofrecerle a Mateo.” Lucas, sin nada mejor que hacer en aquel pedazo de casa que espantar las incansables moscas, se puso su mejor ropa, la que le enviaban los primos y tías de Nueva York, y le envidiaban sus compañeros. Perfumó las llagas que cubría la carne mal comida de su cuello sintiendo el breve picor del alcohol tocando sus heridas y emprendió camino hacia la universidad con la esperanza de ver a Mateo, porque aunque no hubiera clases por la destrucción que dejó el huracán, tenía más oportunidades de verlo en las calles de Moca, que en su pequeño y aburrido pueblo. Lucas llevaba su cabeza en alto, balanceada en casi los huesos cervicales, y con una sonrisa solo en lo que le quedaba de labios, navegaba los obstáculos dejado por el huracán. Ni los postes y cables eléctricos, ramas y árboles, hojas de zinc y cuerpos moribundos pudieron borrar su buen humor. Tenía el presentimiento de que no solo encontraría a Mateo en la universidad, pero que ese día el chico de pelo bueno terminaría el festín que era su cuerpo. Entrarían a un salón vacío y por fin Lucas y Mateo serían uno en un mismo cuerpo. Le tomó horas llegar a la universidad. Su ropa toda sudada y ensangrentada. Limpió el banco, donde tuvo ese corto dialogo con Mateo, de las hojas lloradas por los árboles que aún quedaban en pie. Se sentó y esperó y esperó hasta que anocheció. Mateo nunca llegó. Lucas amaneció sentado, espalda recta, en el mismo lugar donde esperaba a Mateo. No durmió, no soñó, solo esperó. Esa mañana, con la salida del sol, llegaron las moscas fastidiosas que le serenaban constantemente sus oídos. Lucas estaba cubierto de ellas, quienes lamían su carne y ponían sus huevos. Él no podía espantarlas, su columna dorsal estaba tiesa, no podía mover ni siquiera su cuello. Pero por fin lo vio. Mateo, el único en la universidad, llego a verlo. La perfecta nariz de Mateo se arrugó al acercarse a Lucas, quien parecía carne seca al sol. Lucas intento sonreír con lo que le quedaba de labios, pero era difícil al ver la cara de disgusto de Mateo. “Que patético eres,” dijo Mateo. “Me das asco.” Lucas miró como el joven europeo tomaba su alrededor, el desastre dejado por el huracán. Él vio como Mateo nunca perdió de su cara la revulsión que sentía por lo que veía, por la tierra que pisaba. Lucas entendió que ya este sitio lo aburria. Ya la gente le molestaba. Lucas sabía que Mateo iba hacer lo que los mismos dominicanos no podía. Iba a tomar sus cosas e irse a otro lugar por otras aventuras. Buscaría a otro que devorar. Lucas no pudo moverse de ese sitio. Allí quedo como monje en meditación. Los compañeros le traían flores y le hicieron una tumba. Cuando sus huesos se hicieron polvo, fabricaron alrededor del banco un jardín de claveles blancos. White Carnationsby Alex V. Cruz The slender-nosed figure sunk his teeth into Lucas’s lips before their first encounter. It happened in a dream, and Lucas could not fully grasp what had occurred until the following day. He wandered about with the lingering taste of clotted blood when he noticed the guy strolling the hallways of Utesa University without a care in the world. Lucas recognized him by how he strode along, chest puffed and back straight as though the Eiffel Tower were lodged up his ass. His eyes, waters of the Mediterranean Sea. His sultry lips were like long, thin caterpillars. His charcoal hair lacked the texture of “bad” hair. Lucas learned through the undulating waves of gossip that swept through the university that his name was Mateo. The news propagated and intensified with each new flock of girls and guys that gawked from afar as he navigated the sweltering hallways of that small Cibao university. Lucas traced the wounds on his lips with the tip of his tongue, no longer plagued by the agonizing sting of Mateo’s bite. Still, he was intoxicated by the rusty taste of blood. After an exhausting day of classes, he lay on a hard concrete bench by the school’s central garden, peering at the sky as the dark clouds brooded over the ideal time to ruin the life of the daily commuters. “We’ve met,” Lucas heard his voice, and without a glance, he knew it was the Spaniard speaking—the one that caused the entire academy to spawn in a frenzy. The way he pronounced the “S’es” and substituted the “ce” sound for “ze” immediately gave him away. “I don’t think so,” responded Lucas—sitting up on the bench to face him directly—because how could he explain that they had already met in a dream and he could still savor his lips? Deep within his pulsating heart, he suppressed the memory of Mateo’s damp skin, which throbbed to the cadence of a nineteenth-century steam engine. “You know what,” said Mateo. “You’re handsome…” Lucas eluded his gaze, finding refuge in passers-by. His cheeks reddened under the diluted melanin of his skin. “…for a Dominican.” Mateo continued on with his day. Lucas was engrossed by how the wind tousled his hair, and the unforgiving sun chose only to caress his delicate pale skin. He fixated on his swaggering stride until the Spaniard was entirely out of sight. A group of chattering students exited the school and Lucas recognized a class peer. His backpack carelessly hung loose off his shoulder, and his disheveled clothing belied his usually compulsively neat attire. His shirt was bloodied and torn near the chest area. Remnants of his jawbone, freshly nude of flesh, glistened like ivory, and his entire chin and lower lip were gone. Lucas felt a strong pang of jealousy but was comforted by the anticipation: “That’ll be for tomorrow.” Lucas hesitated to leave where he and Mateo first engaged, but raindrops began to penetrate his spiraled locks of hair. It was time to go back home where his mother would surely be anticipating his return with a hot meal set on the table for her college son, pride plastered on her face. *** The third hurricane of the season was approaching. Lucas packed an umbrella and rummaged through his chest of drawers until he found the old, forgotten scarf belonging to his cousin in America. He shrouded his neck as crimson excretions oozed from his shredded skin and absent jaw. Lucas didn’t want to stain the Civilizaciones Mesoamericanas exam the professor had prepared for class. The small and rickety public car broke down on the side of the road mere blocks from the academy. Lucas squeezed passed the other passengers and pressed on, his back hunched against the battering winds and hailing rain droplets, a warning that the hurricane would soon anchor. He reached the main gate, where the watchman slept through the howling storm, fiercely safeguarding the school in his dreams. The stench of decaying souls and damp hair permeated the empty halls. Thin-nosed Mateo, with glistening hair, leaned against the wall and gazed directly at him from underneath his thick lashes. “I want more,” he said. Lucas realized that Mateo was waiting for him. The blood intended for the blushful reddening of desire gushed from his missing mandible and torn flesh, saturating the scarf. Mateo unwrapped Lucas’ scarf unveiling the vestiges from the previous night’s feast. Mateo pressed closer and, with the tip of his tongue, caressed Lucas’ face around his forehead to his temples, exploring down the untouched skin near his collar. Mateo’s mouth widened, his teeth scathing Lucas’s flesh, and with firm pressure, tore a mouthful. An approaching schoolgirl shrieked and fainted at the sight of such passion. Lucas felt for his flesh, his fingers encountered but a stubborn thin layer coating his white bones. His scarf was deemed useless and forgotten on the dirty floor of that school to later become the most beautiful red rose. Already too late to take the exam, and with the professor fixed on failing him, Lucas embarked on the long journey home. *** At his house, he set his soaked books on the flimsy table. His mother stirred the sancocho in the large aluminum pot. “Look at the news,” she pointed with her puckered lips. “The eye of the hurricane will hit tonight and destroy everything.” Lucas panicked at the thought of classes being canceled, fearing he would miss Mateo’s lips all over his raw flesh. Lucas dreamed of him that night, sleeping through the blustering gusts of winds, endless rain, and the macos that squeezed between the wooden planks of the house and searched for shelter. In his dream, Mateo devoured his chest and left arm, and left only bones and tendons. That morning, Lucas awoke to the house and his mother swept away by the powerful gust, never to be found; only his room standing. “Shit!” said Lucas, discovering what was left of his body. “I have nothing left for Mateo.” With nothing better to do than swat tireless flies, Lucas laid out his finest clothes, the ones sent by his aunts from Nueva York, envied by classmates and others. He poured cologne on the exposed ribcage held together by the half-eaten flesh, indulging in the brief sting of the alcohol infiltrating his wounds. Classes were suspended due to the destruction of the hurricane. Still, his chance to see Mateo walking the streets of Moca was better than staying in his lifeless town. His head held high, balanced on bare bones, and a contrived smile with what he had left of his upper lip, Lucas navigated the remnants of nature’s wrath—electricity poles and cables, branches and trees, and corrugated metal and corpses. He was confident he’d see Mateo and was convinced the thin-nosed slick-haired man would continue feasting on his body. They would stow away in an unlocked room and become one in the same body. After hours of trekking to the academy, Lucas’s clothes were a spectacle of sweat and blood. With his one hand, he swept away the leaves on the bench and sat down as best as his weak body would allow. Lucas spent the night on the bench, his back stiffened by dry flesh. Refusing to sleep, to dream, he simply waited. Mateo never showed. With the sunrise, a legion of flies arose, competing for a nip of rotting flesh and repulsive enough to lay their eggs. His body hardened like meat hung to dry. But finally, just as Lucas was beginning to lose hope, he came. His perfect nose wrinkled as he neared Lucas. With the few teeth he had left, Lucas tried to smile but quickly became disheartened as he caught the look of disgust on Mateo’s face. “Patético,” said Mateo. “You sicken me.” The young man skimmed his surroundings and the devastation left behind by the hurricane. Steadfast and beyond reproach, Mateo’s revulsion never faulted; Lucas now understood that this place bored him, the people pestered him, and he was repelled by the soil he stepped on. With deep, inconsolable grief, Lucas knew Mateo would do that one thing Dominicans themselves could not; he would search for adventure in unexplored lands and find himself new flesh to consume. Lucas froze at that moment and never moved again. The world around him retook its rhythm. Classes resumed and Lucas's fellow college mates purchased a tombstone and planted white carnations around the rustic bench where his bones turned to dust.  Alex V. Cruz es un escritor dominicano de ficción especulativa nacido en la ciudad de Paterson, Nueva Jersey. Él es graduado con honores de la Universidad de Columbia en la ciudad de Nueva York con licenciatura en Escritura Creativa y Estudios Hispanos. Actualmente está trabajando en su master de la Universidad de Nueva York (NYU). Alex ha asistido a los prestigiosos talleres de escritura Clarion West 2022 y Tin House 2021. Alex comparte su conocimiento sobre la publicación de cuentos con su comunidad de escritores dominicanos impartiendo clases gratis en la plataforma de Asociación Dominicana de Escritores (@dominicanwriters). Sus cuentos pueden ser encontrados en las revistas SmokeLong, Acentos Review, LatineLit, y pronto en Azahares. También él cuenta con un cuento en Quislaona: A Dominican Fantasy Anthology. Pueden encontrar a Alex en las redes sociales Instagram, Twitter, y Threads usando @avcruzwriter. Alex V. Cruz, a Paterson-born speculative fiction writer with Dominican roots, writes short fiction in both English and Spanish. Graduating Magna Cum Laude from Columbia University, he holds a degree in Creative Writing and Hispanic Studies. He is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing in Spanish at NYU. Notably, Alex is an alum of Clarion West 2022 and a member of Tin House's 2021 Young Adult Workshops. His works have been published in notable online magazines such as Quislaona: A Dominican Fantasy Anthology, SmokeLong, Acentos Review, LatineLit, with two forthcoming stories in Azahares. He is an active member of the Dominican Writers Association, passionately supporting fellow Dominican writers by teaching free publishing classes. Alex is dedicated to sharing his knowledge and empowering his community of writers. Join him on Instagram, Twitter, and Threads using the handle @Avcruzwriter.

0 Comments

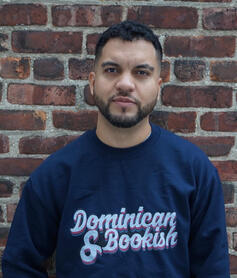

“Working Man”by Armando Gonzalez Maria was in her room, sitting in a chair next to her bed, praying while holding her wooden rosary necklace. She was waiting for her husband to come home. She prayed that Miguel, her husband, wouldn’t work so much. Even on weekends, instead of being with her, he mostly spent it working. His wife used to tell him to stop telling people he was available to work because then he would have a lot of work, and most likely would end up working all week with little to no rest. Miguel didn't seem to mind though. He liked working. Miguel left around eight in the morning. That morning, before he left, as he sat on their bed and was putting on his pants, Maria asked him what time he thought he would be back. He said probably eleven in the morning. While Maria was currently praying, it was soon going to be one in the afternoon. She hoped he didn’t lie to her. After she felt satisfied with the amount of praying she had done, she began thinking of what could still be done around the apartment. Although she had basically completed all the necessary work, she still behaved like an employee on the clock, trying to find something to do so as to avoid being seen by their bosses doing nothing. She first went to the kitchen to see if the floor needed to be mopped. There were some footprints on the kitchen floor, most likely from Miguel’s boots when he was mowing lawns. It should have only taken somewhere around five minutes or less to clean it but she took her time. After she was done mopping the kitchen floor, she checked to see if there were any dirty plates in the kitchen sink. There were only two dishes and three glass cups. She washed them, just as slowly as she mopped the floor. After the dishes, she checked the wooden living room floor, but unsurprisingly, it was pretty clean. She checked all around the apartment to do any kind of cleaning, but there just wasn’t anything to clean. She thought of praying some more, but she didn’t think it was necessary, as she was taught by attending mass over the years, that it’s more about the sincerity behind a prayer than the amount of praying one does in a day. Suddenly, Maria got the idea to go to church. If Miguel wasn’t going to come home anytime soon, then she would go to church, even if it wasn’t Sunday. She knew that Miguel would get annoyed if she did this, and ask her why she went to church, even if she told him there was nothing to do at home. She ignored these thoughts. She changed into a loose fitting dress, brushed her hair and put on black block heels. Before she left, she told her kids if they were hungry, to serve themselves a bowl of the albóndiga soup she made. She told them that she would be back in an hour, and if their dad asked where she had gone, to tell them she had gone to church. On her way to church, although she felt like she was partially going to church out of spite, she felt happy. She was happy because she felt like she was improving, becoming a more resilient person, each time she went to church. This happiness slowly faded away though, when she tried to push open the front doors of the church, only to find they were locked. She was very confused. She thought the church was open at all times. She went to the back of the church to see if there wasn’t possibly a mistake. When she was in the back of the church, standing behind a black steel gate, she expected there to be parked cars and people walking across the parking lot of the church, but instead she didn’t see any cars and or anybody walking. Just then, she saw someone. There was a man, coming out of the side doors of the church, who then started walking across the parking lot. As soon as she saw him, she yelled: “¡Señor! ¡Oiga!” The man stopped and turned towards the direction of where the yelling was coming from. He squinted his eyes, trying to find whoever it was who was yelling. Finally, his eyes met hers, and he began walking towards Maria. “¿Está cerrada la iglesia? ¿Pensé que estaba abierta toda la semana?” “Antes sí. Pero ya no porque gente de la calle se estaban metiendo, y eso estaba molestando a la gente.” “¿De verdad? Nunca sabía que eso podía pasar. Bueno, gracias por decirme.” She walked away, a bit saddened and disappointed. She was looking forward to going to church, especially since it was her first time going to church on a weekday. Unsure of what to do, she began walking home. All she wanted was to spend some time with Miguel. Now she couldn't even go to church on a weekday, which she thought wasn’t asking for much. When she came back home, to her surprise she saw Miguel’s green truck parked on the curb right in front of their apartment. She remembered when he first brought the truck home, it was so bright and shiny. Now, because the car stood out in the sun for some years, the green paint was so faded that it almost looked like there were clouds painted on the hood and roof of the car. He bought the car from his boss, who sold it to him cheaply. When he brought home the truck, it seemed to Maria like a luxury, to be able to have another car. Now, she despised the truck, just the sight of it made her angry, because it symbolized one thing to her: money. Part of the reason her husband had bought the truck wasn't only because he wanted another car, but because he saw an opportunity to make money. The green truck enabled him to go quickly from lawn to lawn, with all the necessary equipment in the bed of the truck. She opened the door to the living room. One of her sons, Daniel, who although wearing headphones that prevented him from hearing her come in, still did not turn around even when a line of sunlight directly hit the screen of the computer he was using when she opened the door. She was about to tap his shoulder to ask if his dad was home when she heard someone coming from the kitchen and down the hall to where she was. It was her husband, wearing his gray, long sleeve shirt, which was now sweaty and dusty and grass stained. Sweat poured down from his balding head. On top of his head were thin, short strands of hair, which were matted down from wearing a hat, which almost made him look like a newborn baby that was just taken from their mom’s womb. He was sucking on his long neck bottle of Corona. “¿A dónde fuisteis?” He took a sip of his beer. “Fui a la iglesia, pero no estaba abierta.” “¿A la iglesia? Pero no es el fin de semana.” “Ya sé.” Her husband said nothing, just took another sip of his beer. “¿Qué hiciste de comer?” “Albóndigas.” She walked to their room. While she was taking her block heels off and putting them under her bed, she asked him, “¿Pensé que ibas a llegar a las once de la mañana?” “Yo pensé que iba a llegar en ese tiempo, pero los chinos querían que hiciera otro trabajo, y los acaparadores también me pidieron que hiciera otra cosa.” “¿Por qué no les dices que no puedes, pero que lo puedes ser para otro día.” “Pues, es que no quiero quedar mal con la gente. Es importante que les diga sí, o no sería capaz de hacer más dinero.” He reached into his pocket to get his black worn out wallet and took out four twenty dollar bills and showed them to Maria. When she saw the bills, this did little to nothing to change the indifferent expression on her face. “Gané ochenta dólares hoy. Y todavía hay dos personas que no me han pagado.” “¿Son las mismas personas que no te pagaron la última semana? “Uno sí. Es el blanco.” “Deberás parar de trabajar por él. Nomás se está haciendo tarugo.” “Ya sé, ya sé. A lo mejor sé.” “¿Ya quieres comer?” “Sí, dame.” Maria walked to the kitchen to heat up the pot of albóndiga soup and got the griddle to heat some tortillas. Miguel took his time drinking his beer and then slowly walked over to the small kitchen. Once he sat down on a chair, Maria asked him “¿Cuántas horas trabajastes?” “No más de cinco horas.” “¿No más cinco horas?” Miguel, unsurprised at his wife’s reaction, chuckled. “Cinco horas no es mucho.” “Y te aseguro que no descansaste.” “Los hombres no se cansan,” he said. “Ya para diciendo eso. Los hombres pueden sentirse cansados,” she said with her face hardened, tired of the joke. Miguel laughed, his head bouncing up and down, and said, “Okay, okay.” Once the albóndiga soup was hot enough, Maria got a bowl from the cupboard and started pouring the soup into the bowl. As she was pouring the soup and albóndigas into the bowl she was holding, Miguel asked her “¿Por qué fuistes a la iglesia a hoy?” “Pues, no más se me ocurrió.” Her husband, suddenly serious, didn’t immediately answer. “No creo que sea necesario ir a la iglesia hoy.” “Ya sé, pero me gusta ir a la iglesia cuando puedo.” Maria placed the bowl of albóndiga soup in front of him. He didn’t eat more than one albóndiga when he asked: “Deberías enfocarte en lo que ser en la casa en vez de pensar en la iglesia.” “No había nada que hacer aquí. Terminé todo.” “¿Y no te vas a cansar mucho yendo a la iglesia durante la semana?” “Si vamos a hablar de quién se cansa más, vamos a hablar de ti.” Her husband laughed. “¿Por qué te rías?” “Okay, pero yo me canso por una buena razón,” he said with a grin on his face. For the first time, she laughed, too, out of impatience for the way her husband spoke to her. “De verdad tienes un problema. No más quieres trabajar, trabajar y trabajar. Dices que trabajas de necesidad, pero te pasas, como si no tuvieras dinero. Algunas veces, en el momento que vienes del trabajo, ya te quieres pelar para trabajar otra vez, no comas muy bien o no me dices que ya te vas a ir. Y cuando–—no me callas, deja mi de hablar–—llegas de tus otros trabajos a la casa, estás irritado, te enojas cuando los niños o yo no te ayudamos rápidamente a bajar todas tus herramientas del camión. Tú solo te haces infeliz por hacer algo que es de necesidad.” “¿Qué quieres que haga? Si trabajo mucho, me canso, pero tengo dinero. Si no trabajo mucho, no estoy cansado, pero voy a tener poco dinero. Si realmente quieres que trabaje menos, ¿por qué no me ayudas o encuentras un trabajo?” “Miguel, tú ya sabes que no puedo ser eso.” “¿Por qué no? Creo que puedes hacer la mayoría de lo que no haces ahora y seguir trabajando.” “¿Qué estás diciendo? ¿Que no trabajo?” “¿Piensas que estar sentado casi todo el día es trabajo?” he said and laughed a mocking laugh, which made him appear like a child. “Ya me estás ofendiendo.” “Pues, no te mates.” “¿No me mato? ¿Tú piensas que pudieras tener un trabajo y llevar a las niños a la escuela, comprar y hacer de comer, llenar la botella de agua, llevar los platos, limpiar la casa, lavar la ropa, tirar la basura, juntar a los niños de la escuela, y dar atención a los niños?” “Todo lo que dijiste son trabajitos que se pueden hacer rápido.” “No se puede prestar atención a los niños rápido, solo se puede hacer lentamente y con paciencia.” Fed up with her arguing, he got up and left. “¿A dónde vas?” “Voy a regar el zacate.” She was going to say more to him, but she knew when to stop talking, because at some point, in the middle of an argument, her husband would eventually start to tune out everything she said, even when she did have a point. She noticed he had barely eaten anything from his bowl. From where she was sitting at the small kitchen table, she could hear him in the backyard getting the hose to water the front lawn. She didn’t know what to do. After sitting in silence for a few minutes, she got up to get her wooden rosary from their room, and started to pray once again.  Armando Gonzalez is Chicano, born and raised in Santa Ana, CA. He has one published story in Somos en escrito called “Haircut” (click here to read it). |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed