El Parbulito |

| Gloria Delgado, born and raised in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, is the daughter of a Mexican father and a Hawaii-born Puerto Rican mother. She and her husband live in Albany, California. One of her stories, “Savanna,” was included in the Berkeley Community Memoir Project’s recently published collection, “A Wiggle and a Prayer.” This is her fourth story for “Somos en escrito.” |

**Painting of San Antonio de Padua, patron of the poor, by Micaela Martinez DuCasse, the daughter of Xavier Martinez, a well-known Mexican artist who spent much of his life in California. Ducasse also taught classes at Lone Mountain when Delgado was a student.

This story is a work of fiction based on historically documented events. All individuals with surnames, including their children, were real people; those without surnames are fictional.

In Mexico tens of thousands of residents, Indians, mestizos and españoles alike, died from intermittent plagues, smallpox, chickenpox, mumps and measles. At times there were so many deaths that the priests were too overwhelmed to comply with church regulations as to the proper listing of entries in the death records, able to note only the date of death and the names, if known, of victims who were interred on that date.

Don Augustín Diaz-De Leon’s child, Pantaleón, died in December 1747, eight months after the death of his father. Pantaleón was three years old. The youngest child, Augustín Miguel Estanislao, was born two weeks after his father’s death, on 11 May 1747. He survived into adulthood, eventually settling in Sierra de Pinos, Zacatecas, where he and Thadea Josepha Gertrudis Muñoz Tiscareño married.

Don Augustín’s widow, doña Maria Antonia Fernandez de Palos Ruiz de Escamilla and el alcalde mayor don Fernando Manuel Monrroy y Carrillo, (witness to the death of don Augustín as well as the executor of his estate) in September 1749 were granted a dispensation to marry. Don Fernando was a widower; his first wife was doña Juana Salvadora Jimenez.

Don Augustín’s father, el alférez (subaltern) don Visente Xabier Diaz-De Leon, was at this time the owner of the Hacienda de Peñuelas. Following the death of his first wife, doña Catharina Acosta, he married and raised another family with his second wife doña María Dolores Medina. Upon his death in April 1754 he left money (including 15 gold Castilian ducats) for his intentions, including 100 masses to be offered for the repose of his soul and for his servants, living or dead.

The ex-Hacienda de Peñuelas, still in existence, is one of the oldest haciendas in the Mexican state of Aguascalientes. Established sometime before 1575, Peñuelas predates the foundation of the Villa of Aguascalientes itself. This hacienda consisted of several self-supporting plantation-like communities staffed and farmed by resident Indians and slaves.

The Cathedral Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, originally known as San Ysidro Labrador, was initiated in 1704 and completed in 1738 by don Manuel Colón de Larreátegui, head of the Mitra de Guadalajara. Its northern bell tower was completed in 1764, the southern bell tower not until 1946.

Sources

All birth and death documents cited are from the following:

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints:

FamilySearch.com and other films on line.

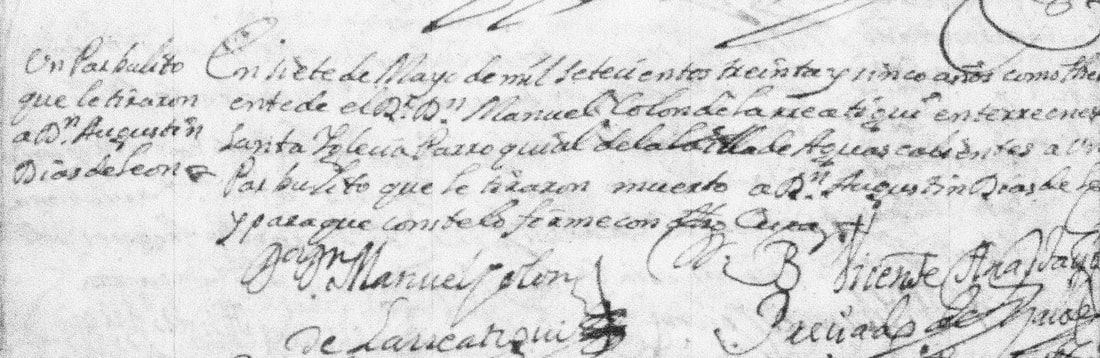

The entry cited re the infant, the parbulito of this story, is from:

Mexico Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, Catholic Church Records

Parroquia del Sagrario, Asunción de Maria

Defunciones 1708-1735, 1736-1748

El Parbulito: Image 530 [Libro quatro de Entierros]

Montejano Hilton, Maria de la Luz:

Sagrada Mitra de Guadalajara, Antiguo Obispado de la Nueva Galicia, 1999

Rojas, Beatriz, et al:

Breve historia de Aguascalientes, 1994

Topete del Valle, Alexandro:

Aguascalientes: Guia para visitar la Ciudad y el Estado, 1973

Vázquez y Rodríguez de Frias, José Luis:

Genealogía de Nochistlán Antiguo Reino de la Nueva Galicia en el Siglo XVII según sus Archivos Parroquiales, 2001

Death Eye Dog

"Death Eye Dog" was a runner up in the 2018 Extra Fiction Contest. See here to read the first, second, and third winning entries and stay tuned for this year's upcoming Extra Fiction Contest.

Houses are lonely when they are no longer homes and nightfall makes the emptiness rattle. Raul walks in the night with his dog. He wears too-big, hooded sweatshirts that hide his face in darkness. This part of San Francisco is grey. The fog dampens the cold, streetlights dim the darkness and the smell of urine rises thick from the pavement. The only glitter comes from the glass chips in the sidewalk that shine in the momentary light of passing cars.

Raul walks smooth and towers over most people on the street. His arms are heavy and solid; his eyes are tired and full of unshed tears. He carries arrugas on his face so deep they sometimes appear as folds. He lives alone; even when among friends and family, he resists communion. Solid as his name, stonecold, like a fallen star who has forgotten how to shine. It is as if he wears a cloak, a tangle of scars of loss that hide the glow of his heart.

Passersby slink away from the walking duo.

Death Eye Dog sinks over the horizon with the morning light. Xolotl, the evening star, hangs heavy in the night sky, demands notice as soon as the bright rays of the sun sink beneath the horizon.

Death Eye Dog, Xolotl, cried so much when the last world, the world of the Fourth Sun ended, that his eyes fell out of his sockets.

Blind, Xolotl guided his brother, Morning Star, into the depths of Mictlán after the Fourth Sun ended in flood. The waters washed all the dead to the underworld, returning the people to their spiritual home of darkness. None were left to remake the world of the Fifth Sun anew. Morning Star, Quetzlcoatl, guided by Evening Star, Xolotl, descended to Mictlán, land of darkness and skeletons. Human bones covered the ground. Quetzlcoatl slashed his wrists, anointing the bones with his life-giving blood.

Xolotl, Death Eye Dog, gathered up the bones in his mouth, carried them from the underworld back to the material world to remake mankind in the fifth and final age of the Sun.

Raul knew a different life before this life he lives now. He had a wife, he had a daughter: he had a home. They are as gone now as if the flood of the Fourth Sun had come and washed them away.

Untethered, he never cried, gritted his teeth instead and convinced himself not to feel. Stonecold. Emotion oozes out the cracks though, or explodes in sudden unpredictable bursts. The dog was to take the edge off alone, off loss, off untethered.

His pit bull is rowdy. Rambunctious. They hold the opposite ends of the leash and pull and pull and pull. Neither ever gives in, even when Raul raises his arm up over his head hauling the dog several feet off the ground.

Raul lowers him down, lays his broad hand on the dog’s head. He doesn’t push down but lets its weight be enough to make the dog submit and release the leash.

His submissions are only momentary: he knows who is boss, but only in the practical matters of food and shelter. That pit never stops being his own dog. He mischieves all the time.

The dog too is big, he is lean and narrow, but tall, taller than pit bulls are expected to be. Raul and the dog’s eyes are the same color hazel, only the dog’s are full of joy and love and play.

A gap begs a bridge between the two, a guided path from the terrible cloak of Raul’s to the dog’s incorrigible joy. Raul ought to be blind with tears by now, instead his eyes hang heavy at the edges, as if carrying a great weight. He goes about now in a darkness as bleak as Mictlán, in a darkness as tight as a straitjacket.

From Mictlán it is possible to rise again as butterfly or bird, to resurrect oneself.

From loss it is possible to rebuild your life.

Winter rebirths spring swells into summer sheds into autumn returns to the barrenness of winter.

Wintertime, darktimes, where it appears that all is lost and nothing moves are crucial times. The earth restores during winter. Its faith never flails at the darkest time of night, during that hour before the sun sets a blood red glow on the horizon, knowing that it must arrive at those dark depths before bursting forth into spring.

Too, to rebirth from the underworld, the dead must first arrive at the depths of Mictlán.

Raul got his dog after he returned from family back to one. Something warm and alive to love in the hardest time of unknowing what next, something to care for when the dawn was nothing to set his cap at, a guide for the darkest parts of night. He lacks the morning star, the blood of life that ushers in a new dawn.

Stonecold, Raul forgets to look for the sun rising, for the red glow on the horizon. He spends his days waiting for it to be night and the night to be day, until the time that will pass, does. He tries to form a new family, one of friends, stopgaps living with partying, something to fill the time and space. The gap between he and the dog becomes an abyss, slowly, like water run through a crevice carves out a canyon.

Raul and his dog walk up 21st street, past the crowded-at-night basketball courts, the stoops where people sit, talking, drinking and hollering out to passersby. He had set out for a walk to take the chill off alone, but the darkness presses tight. They turn onto Mission, head over to a bar where a friend bartends. Raul ties his dog up outside and walks in to where a beer and a shot of tequila are sliding across the bar to him as soon as his shadow fills the doorway.

It is Guillermo’s bar, meaning, the bar where Guillermo works, not a bar that Guillermo owns. The lights are dim and throw a reddish cast to the bar, except for the bright white light that highlights the rows of bottles. There they are, working and playing, all his crew, and Miguel shouts, “Eh, man, where’d you crawl out from. You missed a great party last week, ha! Ask Devon ‘bout it,” then starts laughing maniacally, like a machine gun. Raul asks, and Guillermo sets out a row of shot glasses, fills them with tequila and then everyone reaches in and grabs one, throws them back and then gets back to work on their beers.

Devon launches into a story, “So this girl, I see her and she looks amazing and she’s alone so I give her a lil’ tap, just a tap not even on her ass, but on her hip, and then this guy over on the couch starts glaring at me and comes over and pushes me across the table,” and Guillermo starts laughing, “and I came in and—”

“Dude, shut up, I’m telling the story and—,”

And Raul’s eyes are lit up, anointed by the liquor, “Hey Guillermo, how about another round over here,” because that’s what they do, is keep going until Guillermo calls last call and then the crowd spills out onto the street, leaving just him and his boys and they head into the back and do some lines and their speech becomes sharp like knives and their laughter like metal and they leave, finally, and head over to where Miguel knows somebody spinning and it’s going to be good, man, and they go and they stay, inside in the dark cut with bright pulsating lights even while sun rises, bloodred, spilling dawn over the land.

Winning Authors' Stories

in First Annual Extra-Fiction

Writing Contest 2018

We thank Ernest Hogan, considered by all who care for the genre as the Godfather of Chicano ex-fi, who was the judge for this first competition.

First Place Winner:

Fatherly, dragonly, motherly . . . love, luck and touch

Awakening, flexing her three-foot-wide mouth, Tieholtsodi said to herself, “I can’t sense the children, even through the Portal. For some reason, they’re out earlier than usual.”

Looking over her tentacles for new signs of aging decrepitude, the water-dragon snorted. “Older than the dinosaurs, but at least I’m no fossil.” For eons, she’d talked to herself to counter the loneliness of being the last adult of her kind.

All yawned out, she scanned the dimness of her sub-lake cavern, located at the bottom of what the humans called Lake Powell. Drawing on spirit-power, she appealed to the super-ascendants. “Blessed Holies, grant us some light.”

Silence.

“As usual, they’re responsive as a sacred mountain.” She shot out a tentacle, missing a blue catfish.

Older and wiser than a mountain, Tieholtsodi hadn’t expected an answer. “So, what good are goddesses who don’t lift a finger to help?”

Stretching her five tentacles limbered her awake. “I’d pass for a fat octopus with a squashed head, nowhere as impressive as when the Diné first appeared.” She scraped at pill clams nesting on her amber hide. “So much of me fades. If my worshippers saw me now, they’d laugh their little red tails off.”

Feeling into the dimness, she traced the rock walls. Little had changed in the millennia since she’d excavated the haven for her family. “They’d better return soon. I worry they’ll be caught by men. Or the alien dragons.”

§

Miles away, both of the young creatures had been taught not to venture far. But today the world was filled with wonders.

Too young to speak, one telepathed to the other, How can we resist?

Underwater currents carried them, banging them against rocks, dragging them through smooth silt. As if the lake wanted to play-wrestle. Just like Mommy!

Up ahead, colored lights flashed. But no matter how hard and fast they swam, they couldn’t catch them.

Oh, and sweet fishies! The waters tasted of burnt trout.

Might be a present from Blessed Holies, for our achy bellies!

The aroma lured them on.

§

Rising quickly, Tieholtsodi bumped the spikes running down her back against the ten-foot ceiling. “Gagh! Serves me right. Should’ve taken us to the ocean and found a bigger cavern with scrumptious starfish and octopi. What was I thinking!”

Necessity, not thought, had landed her family here. Over millennia, the Great Inland Sea had receded, leaving the Colorado River to gouge a path through the rolling hills and desert plains.

She brushed her rough bristles and sniffed under tentacles. “I’ll have to head mid-lake to rid myself of this bottom-rot smell, after my babies return.

“Of course,”--she sighed--”first they’ll want to play Pile-on-Mommy.” Pretending interest in something else, the children would attack, knock her down and pummel her with their bodies.

She chuckled, and checked her talons for splits that might cut the children. “Should’ve been born with an octopus’s suction cups.” She withdrew the talons, like when hugging her young. “Ah, if motherhood were my only responsibility. But, no! Had to be born a tailless, wingless, flameless monster dragon. Fire-breathing would’ve been good, like the Alien Dragons sort of have.”

Dangling a tentacle into the current, hoping to lure a large fish, she sensed manmade chemicals, the lake’s rising temperature and falling volume. “The big fish disappear, like the red people prophesied.” For a century, the lake had been dying. “Someday we’ll have to find a Portal to the clean, open seas.”

Teeth latched onto her tentacle, making her pull in the catch. “What!” She exchanged bared fangs with a thrashing, six-foot alligator gar. “The children will be pleased! Haven’t seen one your size in hundreds of moons. Where--” Crunch! But something was wrong. The catch had been too easy.

“You’re bait! Someone sent you, thinking I’m a stupid monster?” Natives respected her, and other humans dismissed her as a myth. “That only leaves the Alien Dragons.”

If she’d gorged on the gar, she might’ve missed squeals coming through the Portal. “My babies!” She bashed the fish against a boulder, flung it aside. Flattening herself manta-ray-like, she probed for her young’s auras. “Found them!” Relieved, she radiated an eddy that rolled the boulder onto the gar.

Still, more was wrong.

“They’re not in the lake! They entered a far-off river. Blessed Holies, why’d they…. Have to find them before they’re spotted. Or worse.”

§

Commander Brondel mumbled toward his desk, “Soon we’ll be free to conduct more than occasional hunts in the canyons above. Without worrying someone might detect us.” He’d done well selecting this site underneath a desert. Uranium and coal mines, scattered native tribes and occasional tourists weren’t much of a worry.

He switched off a monitor. “Father, today’s the day. You’ll be proud.” On a desk sat the funereal holo-pic of Father, a fine example of his species, in uniform, tyrannosaurus-like, though with shorter tail and thicker forearms.

Brondel straightened his tunic, ran claws over his hand’s olive-tinted scales. He saluted the holo-pic. “Almost everything’s ready to complete our dream. I can almost smell it.” He grimaced from inhaling deep--the oil-sodden walls stank of the raw fuel humans had extracted, despite the incessant hum from air-filtration scrubbers.

Earlier, leveraging his influence with the Council, he’d proposed more surface explorations. As he’d testified, “A four-foot taller species--two hundred pounds heavier, with twice the intelligence and technology of homo sapiens--shouldn’t be denied fresh air!” He’d barely gotten their approval, and received no laughter.

Brondel checked that his milled-rock desk appeared orderly. Brushing lint off his tunic, he was ready for his Second-in-command. “Father, I expect he’s taken care of everything. But you always said eye-to-eye is the only way to gauge loyalty.” He massaged his belly, hoping for good news. Especially about the little monsters.

§

At the river’s mouth, the young ones turned upstream, chasing the tasty morsels and funny lights.

We’re close!

Later, Mommy might be mad, but they were just babies, as she called them.

What’s a kid supposed to do, anyway?

§

Hearing excited cries, the shaman Tomás halted his spring-cleaning. At the doorway of the adobe cabin, he lowered his head, wiping his hands on worn overalls, and scanned the horizon, thinking, The noise came through a Portal, miles away. He’d blocked off the one in the cabin, well enough.

Sangre de Cristo winds washed him, cooling his toughened skin, sweeping wavy, black locks about his ebonied face.

Tomás couldn’t determine the species he’d heard. They were young, possibly in danger. He inhaled deep. “Nada. Except wildlife and toxic soot from the Four Corners’ power plants.” The locals gossiped about how the shaman-hermit talked to himself, as if communicating with unseen spirits.

During the centuries separated from his colleagues, he’d heard other gritos of distress. But his job of Sentinel took precedence, leaving no time for a wife or family. Ever since the ancient Aztecas discovered the Dragones, one shaman dedicated his extended life to defending the Portal openings, keeping the aliens shuttered underground. Mysteriously, and luckily, they couldn’t dig their way out; the Portal was their only exit. Their science could access it but was inferior to shaman magic, so few snuck by Tomás.

“I could check on those little niños if I had my Superman cape.” He chuckled, glanced at the mesquite cabinet holding his depleted cape. “Too bad cleansing couldn’t remove the dragons’ acidic sangre.” Alien blood eroded his gear and weaponry.

“At least my macquahuitl sword”--hanging from a cottonwood viga above--”the gift from Moctecuzoma I, still shines pristine.” By the tip of its blade, he spun it.

“I suppose there’s una chansa in a million the Holies will answer those niños. Sí, señor, the day brujo-witches learn to fart red rosas!” He resumed his housework and dampened reception of the shrieks. They’d hurt more than his ears.

§

Overheated from traversing the lake, Tieholtsodi coasted. A message came through the Portal. “The Dragons took my babies! Why? We’ve all lived hidden in our caverns for eons.” Heady breezes dried her exposed hide while she considered the message.

“They want me to kill the Sentinel? That means their powers are fading and they’re ready to…. They learned nothing about disturbing the Balance.” Like when their shipwreck exterminated the monstrous dinosaurs.

Tieholtsodi too was a monster, but one who never killed sapients. Diné legends attributed murders to her, from drowning victims she ate. Those weren’t her doing; she simply took advantage of the accidental deaths. Except to save herself or her young, murder was abomination. However, the message left no doubt.

“Blessed Holies, if I don’t kill him before nightfall, I’ll never see my babies, again.”

Sinking, she drifted, not righting herself against currents, nor worrying what direction she drifted. “I can’t let--”

Deep-lake gars took chunks out of a tentacle. She barely sensed the teeth, or much else, and sank into colder depths. The gars fled.

“I must--” She hit silt-bottom, her torso spreading, preventing sinking. Words blubbered out of her jagged mouth, “Must save them, without committing murder. Oh, Holies--how?”

Unanswered, an hour later she’d figured it out. Rising from the ooze, she swam to meet her motherly responsibilities.

§

Ready for his meeting, Brondel punched his toned-as-rock abdomen, wishing more than vacuum-dried seafood was behind it. “Like pumas or cattle the scouts bring back, huh, Father? Good thing hunting’s still in the cadre’s blood.”

Normally, the genetically engineered “perfect” soldiers were tasked to assist and protect the scientists and their research.

“Not hunters, only chaperones for the study of the universe,” he said sarcastically. “Grumph!”

But after a wormhole had swallowed their vessel, they lost contact with their home planet. The crippled ship entered this solar system, crashing in the cataclysmic Impact that created a sulfuric-acid deluge exterminating nearly all dinosauria.

Brondel actuated a holoscreen that flickered from bad connections and jerry-rigging, legacies of the Impact. Besides technological losses, the crew barely held onto principles of non-intervention regarding the humans’ civilization. Faith in the original mission faltered. On his deathbed, Father had predicted imminent colony-collapse. To salvage their species, he’d raised Brondel, special.

“Cadre’ve needed new goals like I need a bloody steak. Confinement’s ruined them.” Brondel flipped between holoscreens. “Father, you trained me to lead us out of our cages and into hunting grounds of our choosing. We’re warriors, not worms.” Grumbling, he checked the monitors--of the shaman, the Diné monster, and its offspring.

“The Council suffers from senility. But if they discover our plan, I’ll be arrested…. Today, everything must go perfectly.”

The door was ajar, and his Second-in-command caught him off guard.

“Sir!”

“Your report, soldier?”

“We captured and locked up the two creatures.” He gestured toward the holoscreen. “Your idea of bright lights and cooked fish worked. They followed them straight into our trap.”

“Excellent. Does their birth-mother understand our demands?”

“The observation team reported as much.” He gave his superior a curt grin, without looking him in the eye.

Brondel tried smiling. Military Code dictated it unwise to show emotions around cadre, but he wanted rumors about his optimism to spread. Troop morale and loyalty must center on ME! One great smile from their leader today could sway the doubters. The kidnapping was the first step; the next ones would test every soldier.

I was smart to promote this one. He’d only have been more perfect if he’d been born my ... son. “Keep track that the freak does as told, or she’ll never see her offspring again. Even though we’re limited in getting that shaman, she’s not.” Brondel’s stomach rankled with hunger, for raw meat. “Go.”

Second glimpsed the monitor. The young ones jumped off walls, wrecked furniture and crushed containers. Their squealing reminded him--

“That is all!”

Second returned the fist-salute, spun, tripped and exited. Brondel moved from the plump dragonlings, to the holo of a co-opted satellite. “All, until we take over,” he mumbled. The blue planet overshadowed the gunmetal-gray walls.

“I’ll finally deal with the damned shaman who escaped your attempts on his life.” Grimly, he swore, “Your son will yet rid us of this meddlesome priest.”

He double-checked the door and let loose his cackling. He loved the humans’ literature. Who knew? One day his soldiers might give him a new title. “King Brondel might have a thread of truth to it, Father. The future holds ... possibilities.” He gazed at the youngsters. “Including some delectable ones….”

§

To reach the Blessed Holies’ ethereal realm, pleas and prayers skipped across dimensions of space and Past-Time, avoiding pulsars or disturbing other supernaturals. This involved no luck, so most requests arrived.

As super-ascendants, the Nine Holies sculptured island volcanoes or splatter-painted the heavens with mosaics of comets. However, they seldom answered mortal prayers; wise, maternal guidance demanded minimal meddling.

They’d heed recent pleas because the blue planet’s Balance might be disrupted.

Instantly and nova-bright, the Holies converged on an exoplanet and sat, rimming a crater with a necklace of auras. The Holy, Grand Ultramarine, began. “We heard from our old friend, Tieholtsodi.”

Sky Blue winked and cocked her head sideways.

“Also, from others. I sense we yearn to involve ourselves.”

Everyone nodded sparkles.

“So we shall talk, bearing in mind our original commitments.” The Holies had forsaken mortality to acquire the powers to begin a new world, as any female would have. Still, deep in their auras, memories of their mortal pasts glowed.

“You mean I cannot make ‘a heav’n of hell?’ Sky Blue mischievously raised her eyes. “Shake ‘the lowest bottom of Erebus?’” she giggled; she loved watching Earth life.

Drawing back, she held a plasma bolt, spear-like. “Merely once, I’d relish casting down a lightening--”

Choking, she flushed purple, teetering.

Everyone gasped; no Holy was shielded from fading under space-time. Her brethren streamed over, stabilizing her with their energy.

Grand Ultramarine rolled her lips. “These prayers link to planet-wide conflict that would disturb the Balance. The scenario’s intricate, complicated.” The Holies depended on tiny conjurings to influence reality, otherwise, never moving one wisp.

Calmed, Sky Blue acted less pixyish. “Fate hangs by a thread not of everyone’s making. We have one day to decide.” So they talked. Debated. Pondered. Nuanced. For thousands of instants of time. And reached consensus.

Grand Ultramarine smiled. “This method will prove effective.” Nods all around. “With the lightest touch.”

Pleased with their decision, they chorused, dancing across asteroids. Their merriment rustled dark matter out of a black hole. Three Holies soared over, one saying, “I never tire of these chores.” They nurtured the material back to sleep.

§

Out front of his place, Tomás added spruce logs to his rock-lined fire pit. “The Portal stinks of demonios, hate and fear. Like datura-drunk bruja-witches at a bloodletting ceremony marking the vernal-equinox ending of a fifty-two-year cycle. It’s that crazy!

“But, Holies, it is no brujos--it’s my nemesis, the Alien Dragones. Duty calls, and not the Hispanic kind.” He entered the cabin.

The young ones were likely pawns in a plot, their cries auguring an impending encounter. “Hopefully, I have time and,”--he patted pockets--”prepared enough.”

Suddenly, moss-like fog spurted from walls, spread, choking the interior. “Chingau! Those pinches Dragones!” The fog cemented his feet, quickening his breath. Attempts to dislodge himself made him sweat more than move.

“Bueno, Holies, first a conditioning-spell to free myself, and one to protect my home. Something comes….”

§

Second stood stiff-straight by the desk. “Commander, the creature’s entered the Portal, heading for the shaman. We neutralized him so he’ll be helpless when it arrives. With equipment malfunctions, we don’t know how long it will last.” The word malfunction reminded him he wore a locket with images of his children, draped underneath, on his neck. Really, a minor violation.

“Excellent. Now, what news about our … contingencies?” Brondel was disappointed Second gazed at the screen of the offspring. Removing weak females from our species strengthened us. But this one wavers, probably because of his children. Brondel hadn’t sired any chips-off-the-old-tale; that might’ve ruined Father’s dream. Still, men are more dependable when they believe their family’s threatened. Better deal with that.

“Yes, Commander, the … contingencies. The vault’s stocked, but it was the only place to confine the ... creatures. Whenever you say, we’ll remove them and, after it’s replenished, we’ll escort the Council inside.” He averted the holoscreen.

Brondel loosened his jaw, staunched his anxiety. “Something bothers you; that’s expected. You were raised to protect elders, not lock them up.”

Second checked clawing his locket; it would’ve disappointed his superior.

“We cannot eliminate the Council. That would go completely against Code.” Brondel’s firm tone and step-forward forced his underling to look him in the face.

The green-pupils stare made Second shiver. “I know, Sir.” He scratched his hip, to relax. Strings he loosened floated; one, vacuumed into the rickety, circulation system. A presage of the Council’s fate.

To ease his man, Brondel snapped a smile. “If you haven’t guessed, it’s no contingency; it’s our great leap. Always was. Before, our antiquated, non-interference principles held us back, but they never should’ve applied to a shipwrecked crew. Tieholtsodi eliminates the shaman, the Portal’s wide open.” Brondel cleared his throat; Second tightened his posture.

“Once groundwork is completed, we’ll prepare the invasion. To freely walk the planet, again, to live as superior, sentient beings, inhaling atmosphere, not,”--his arm swept the room--”stank, recycled air…. Your offspring’s’ health suffers here. Imagine how they’ll thrive outside, without fear of humans.” He flushed from perfectly targeting the man’s emotions.

Second visualized he and his young running through grassy, flowered, sunny fields. Suddenly the vision fluctuated to the cold, rocky underground where they played chase-hunts. My commander’s smart and bold, he thought. But did things have to go this far? He set his jaw. Can’t show doubts.

Brondel wanted Second join in the dream. “We could enjoy something better than stinking seafood or reconstituted dino meat! Thick, bloody steaks. Like, The Great Brontosaurus Banquet!” He howled, gnashed his thick tongue. Following their shipwreck, soldiers discovered that surviving dinosauria made great hand-to-hand adversaries. And delectable game. Rumors about the quasi-cannibalism drove some men insane.

Second scoffed; hardly anybody believed the Banquet feeding-frenzy anecdotes.

Brondel gripped Second’s shoulder, their shared hilarity, done. He worried he might’ve sounded too-- “What do you think, Soldier?”

“No--I mean … yes, Sir!”

“Excellent. Keep me updated on the monster, plus, the shaman.” He glanced at that screen. “He already regained consciousness?”

Second lowered his eyes. “I thought we’d delay--”

“Forget it; the monster will dispense with the old pest. Also, have Comm provide me real-time surveillance of all cadre, to make certain my orders are followed.”

Tensing, Second raised his chin. “And the ... children?” He sighed, imagining his own.

§

If they’d known what was planned for them, the youngsters might’ve found their strange cell, less delightful. But it was more fun than cages the dragons had locked them in.

What’s this do?

This place had wood and metal stuff great for playing with.

This one tastes no good and is no fun! They’d nearly run out of ideas for new games.

When’s Mommy coming?

§

“Whatever the fate the shaman meets,”--Brondel cracked knuckles--”you have your orders about the little monsters. If their parent dies, we definitely don’t want revengeful orphans on our tail. Even young claws and teeth shouldn’t be underestimated.” He patted Second’s back, urging him out.

The dark walls curbed Brondel’s rising spirits. He could use larger quarters. “How propitious--the Council won’t need theirs!” He laughed, not hearing Second outside the slowly shutting door, stopping to scrape his boots.

“Father, perhaps the officers should celebrate. Hmmm, is little monster as tangy as fresh baby bronto you described? They’re not enough for a feast, but they’d work as appetizers. That don’t stink of fish. Some tender, young--” He wiped spittle. Never do that in front of cadre; they’d think I’m weak.

Nor could Brondel see his aide scurrying off with scrunched brow and eyes.

§

At the bottom of a waterfall, Tieholtsodi faced the Portal that would transport her into the shaman’s home. She sensed he’d blocked it, but not to stop her. From doing what she must. “If my babies knew what I’m going to do, would they forgive me?”

As ominous as her next task, the Portal glared, beckoning. Swimming in, Tieholtsodi broadcast a final appeal to the Holies.

§

Tomás knew that freeing myself had been too loco-simple. “Dragones’ science is usually more difficult to undo. They weaken. So what else will they use?”

He began stripping the cabin of native rugs, hand-hewn furniture, eventually setting everything outside. “No sense letting my stuff getting chingado-ed.” Items only hung from stuccoed walls and the wood-latias ceiling. “Now we can cumbia!”

Outside he knelt by the fire pit, hoping gathering clouds weren’t a threat. The Dragones had thrown everything imaginable at him. “And a few, unimaginable.” Like a pewter figurine that tried hypnotizing him, eroding his spirit and will.

“Luckily, true magic imagines more than unearthly science.” Burning sage for a cleansing, he wafted it toward the cabin. Done, he scanned the valley.

“What mierda is next? Dragones with ray-guns? Híjole! Better go for my own blaster--some mestizo ambrosia.” His feet scattered cabin dust. “Where did I leave that half-full botella?”

Suddenly, an amber fog flowed from cracks in the walls.

“No more games. They’re fumigating for something bigger than ratas--me!” The fog blinded him. He rubbed his eyes into tears.

Through clouded vision, from the farthest corner, log-thick tentacles rose, blue talons flexed hungrily. Deep growls curdled his hair and heart. Overhead, mounted tools and weapons shook from a huge advancing, lumbering form.

Somehow, the Dragones send Tieholtsodi against puny me. “Qué quieres, Ancient One?”

No answer.

Must even up the weight, if not the odds.

Tomás lowered his palms, sucked life-force from the flooring and underlying earth, infusing his body with mass. And charged, a bison bull at full-run. Floorboards rippled, rusted nails screeched.

§

Salivating about the outcome, Brondel watched his intended victim duel the assassin-monster. “That shaman was a character, not that he’s dead yet.”

On-screen, makeshift translations streamed underneath. Not totally intelligible, coupled with the man’s swift gestures, they amused Brondel.

“Father, we’ll never enjoy chase-hunting him; the shaman soon goes dark.” Licking drool, he switched the monitor to full-view, leaned into his creaking seat, cackling.

§

Beefed up to nearly a ton, Tomás hoped his enchanted mass would at a minimum stun Tieholtsodi. Reverberations from their collision cracked windows. Ricocheting him like a steel spring off his cast-iron, tortilla comal.

Tieholtsodi scratched her itching belly where she’d been hit. She telepathed Tomás, I’m sorry!

Slammed against the wall, his vision clouded. I harmed the creature not one chiquitito bit. He needed a weapon. Pointing bunched fingers at a thrusting-spear, he charmed it to drop into his hands. He swung at groping tentacles. Phoot! Two sagged, lopped half-off.

“Grraah!” Tieholtsodi rolled onto her wounded side, grasped a doorway and a beam. The shaman heard, You’re as formidable as a century ago. But I cannot fail--

“A dissipation spell may convince you to leave.” Tomás drew bundled datura twigs from his pocket. Cast them and sang in Náhuatl, “Xotla cueponi!” They grew as commanded, enchanted twigs turning steel-hard, penetrating Tieholtsodi’s spine.

“Grraah!”

Tentacles buckled like serpents; the creature removed what it could, broken splines waving. Resin seeped in, sapping its fury and strength. In Tomás’s mind, she screamed, I have no choice! Tentacles raised and yanked him close.

Fetidness flooded him, almost making him faint. He turned, fangs gashing his earlobe. “Hijo de su--!” Spotting a bottle behind the creature, he mumbled in Náhuatl, “Igualaz.” Flames darted from his twitching fingers, bursting the bottle into igniting.

The Mexican Molotov-cocktail rocketed toward Tieholtsodi.

“Grrrr!” Fire flared up and down her back. She staggered, fell, smothering the flames. And dropped Tomás.

Before she recovered, Tomás formed his arms into a circle. Green lightening shot out, energizing the Portal.

Still stunned, Tieholtsodi latched onto walls and fought the Portal’s suction. Tentacles screamed--steel on glass--keeping her in position. A tentacle knocked Tomás over and wrapped onto a beam. Cabin walls buckled tremor-like.

The obsidian-studded macquahuitl rattled. Dropped with a whoosh from its hefty weight. Cleaving Tomás’s thigh. A slab of bloody, red meat flapped open-closed.

“Ya no con tus pinch--” Screaming horrific, he barely heard Tieholtsodi’s challenge. Of suicidal sacrifice.

§

Bored playing with stuff, the youngsters sighted something new. A metal-green string flew by, exciting them.

Let’s get it!

Their squeals echoed down the corridors and out into the glistening Portal.

§

Breathing fast, in agony Tomás gritted teeth and pulled the sword.

But it was stuck.

Again he jerked. A head-slap sent him tumbling. But at least his grip-lock freed the sword.

Standing, shaking, he raised it, chanted, empowering it with blood-spirit. As he launched it at the creature’s head, the two opponents half-heard the wails coming from the Portal.

Tieholtsodi jerked her head. The sword hit. “Graah!” She writhed back and back out the Portal. That blurred, then silenced. And disappeared.

Tomás collapsed. Breathed. Checking wounds, he fingered the gashed thigh. “Demonios! Just what I needed--more clean-up.” Hobbling, he found the fishing tackle. After three quick tragos of mezcal, he sewed away with hook and line.

§

Tieholtsodi’s final roar ruptured Brondel’s speakers, static multiplying. Half of his plan evaporated when the wounded creature left possibly to die elsewhere.

“Worthless. Unholy. Fish bait!” He killed the monitor, yelled, “Lights!”

Brondel had allowed for this. Now he’d resort to claw-sized explosives used to map underground formations, shelved since homo sapiens appeared. The Council wouldn’t be around to stop him. “Father, even shaman magic melts under a hypertronic detonation.”

“It will alert the earthlings, but we’ll strike before they can. Victories will ease doubts about my decisions. With cadre, anyway.”

Wham! His tail-thump shattered a chair.

“Hah! I’ll claim we had to pre-empt them. First, better check the soldiers that needed watching. Really hate worrying about Second, but he’s a father.

“If he doesn’t see to the meaty imps, maybe I’d better do it. Then, I’ll check on the Council. Lastly, incinerate that shaman. Into cosmic dust.”

§

On his porch, breezes dried mezcal droplets from Tomás’s lips. “Qué bueno I found anesthetic.” He chuckled, tying off the fishing line. “Chíng-- ... Now, something about Tieholtsodi wasn’t right.” He’d never meant to slay the creature, especially after matching her voice-signature to the young ones. “Maybe its attack involved their welfare.”

As he’d launched the sword, he and Tieholtsodi heard the children howling. Triggering Tomás into instinctively twist his wrist at the moment his slashed leg gave way. His spear had bounced off her front fangs, instead of piercing the skull.

He doused the wound with mezcal. “Hí--jo--lé!”

Taking a snip, he said, “Blessed Holies, did its niños make Tieholtsodi duck or did you make us both flinch? Otherwise, I might’ve slain her.”

Tomás wished the Holies would send a clue about the future. The Dragones must’ve observed the battle and would adjust. “Holies, do I wait or enter the Portal, into their cavernas?” Slapping the bottle on his palm, he wondered if he’d just taken his final drink.

§

Holding his breath, Brondel watched Second, on-screen, wandering, hesitating, speeding down the wrong hallway. “My underling acts female-ish.” Brondel dreaded that his favorite might falter. “Must I ... remove him, Father?” The mumbling he heard didn’t allay his fears.

He’d anticipated even this disappointing betrayal. “Father, his emotions could ruin everything.” He contacted another soldier, giving him special orders.

§

Shivers dogged Second’s every step down the hallway. Disobedience would end more than his career. Warning the Council endangers my children. Whatever his reasons, Code required termination of his bloodline.

But children are children, even the creature’s. His guts wrenched with indecision. Committing infanticide, I could never look at mine without remembering ones I’d slain…. “Shouldn’t have followed his insanity!”

He’d free the creatures, notify the elders, then try not worrying about his young. Code dictated his suffering would be short.

Hurrying, he cursed something stuck to his boot. And didn’t see a soldier turn the corner, drawing a weapon.

§

The thought of blood about to flow aroused the assassin. Training had nurtured a cruel streak that earned him the position.

He raised his blaster, guessing he couldn’t miss notwithstanding the dimness. He tried ignoring childish whimpers coming from somewhere. They could be his next assignment! His trigger finger trembled.

§

“Damned thread!” Even busy, Second wanted his uniform neat. Not stopping, he stooped to clean his boot, lost hold and tripped. Too clumsy when I’m hurrying.

A heat-blast cut into his shoulder. Clothes and hide steamed and hissed. Momentum carried him forward, and he rolled hard, curled into crouching, pulled and shot his weapon.

Decapitating the attacker who crumpled. Blomp!

Brondel sent this assassin. No doubts now! He swooned, gushing blood. “Aahh! Gotta get to … wallcomm.”

§

Brondel never believed in the ethereal or luck. Heading out from his room, he mumbled, “I prevail because of your genes, Father, training, and my T-rex mind-set. Don’t need any luck.”

For no reason though, he grabbed his ceremonial sidearm. Several hallways later, his reflexes sparked--Second rising when the man should’ve been dead. Brondel fired, gouging a pit in Second’s back, knocking him flat. “Shit! A kill-shot. Couldn’t help … myself”

He swayed, his eyes turning inky, till he saw the shoulder wound. “Guess the assassin tried…. Second, did you foul up anything else? Sorry. Plus, your offspring will pay.” He wiped sweat from his aide’s brow.

“Uhhh!”

“Would you’ve been faithful if I’d been your….” Brondel skirted him, kicking the assassin’s head, hard.

He ground molars. If the Council knows, my plans are worm bait. Otherwise--he licked lips--I have time to check the little snacks. The slight detour would make him feel better, maybe erase Second from his mind.

§

Barely stirring, given his wound’s size Second knew death approached. But Brondel had left him an out. “Deliberately? Can slow ... bleeding. Maybe save ... my….”

He tuned his weapon to low-setting, used it on himself. “For both of my...!” Drawing on love for his children, he baffled his screams to not alert Brondel. Heat-spurts cauterized the hole. Drenched in tears and sweat, Second dragged himself across gravel toward the wallcomm, nearly fainting with every tug.

§

Trapped for hours, they knew Mommy would soon come to their rescue.

We’re hungry!

How she’d laugh when she found them.

Then, tasty fish or serpents! They hoped she’d show soon; they were so hungry, they could eat a dragon.

§

Clutching the wallcomm, Second grimaced, but he’d warned the elders. “The tide turns. Faster than … I bleed out.” His self-triage had given him time, but cut blood flow to vital organs. “At least the children….”

According to Code, self-sacrifice overrode disobedience; his corpse would exonerate him. He gasped from a torturing chuckle.

And Code guaranteed a hero’s children bright futures. “If I wasn’t. Grotesque. Would’ve called for them ... what a father--”

His corpse slumped onto the chilled gravel.

§

“Excellent.” Brondel assumed men guarding the vault had gone for the Council. A monitor showed the out-of-control creatures inside--hyper, hungry as him? He smacked the wall. It didn’t matter; they were plump enough. This won’t take long.

Tapping the bolt-release, he envisioned taking them out, right to left. He set his blaster to medium. Just lightly toasted.

The children sensed something.

Wait, what’s that? Mommy! Run, hide!

They huddled by the entrance.

He couldn’t accidentally kill them, like Second. Remembering his aide’s ghastly face, he bit his lip clean through. To erase the painful image, he yanked the door, leapt in, positioned low, to fire. He slipped on gummy saliva, or worse.

Get him!

Their bodies blocked his view. Crushed his throat. He lost the sidearm. Floundering for it, he knocked it outside. “N--ooo!”

§

Mommy might’ve sent the strange dragon. So, they’d both withdrawn their talons to not harm it, much. That would’ve taken the fun out of it. Mother had shown them that the day she taught them to never chase or eat dragon.

Hopping off the strange one, they scampered into the hallway.

Find Mommy!

The last one out playfully slammed the door.

§

“Father, the verdict will be swift.” Brondel cleaned off shredded cushions. “Code justice won’t even allow me makeshift lighting, like after the damned Impact.”

Tearing insignias off, he blotted at small wounds. “Why’d the little scoundrels not inflict more damage? They’ve got the claws for it.” He hadn’t anticipated deviousness from such young things. “They weren’t playing games, Father. Must’ve been survival instincts.”

Brondel couldn’t appeal to the Council. “Sensory deprivation is mandated for our crimes.” He flared nostrils, as if they’d capture light for the future.

To survive isolation, Brondel had only his genes. Despite no light or sound, tech would keep the vault livable. “Father, this is home, now.” He fist-saluted the imagined holo-pic. “Worse than being buried under a sacred mountain.”

Fluffing cushions, he sat, fearing the approaching silence. “Even a shaman would’ve made for decent company.” He’d never again hear anyone.

The droning, air-filtration system drove something into his eye. Dampers engaged, drowning out what might’ve been his first sobs.

§

The fire pit’s wavering flames sucked at Tomás’s eyes. “It’s over. No more of their meddlesome mugre, today.” With a piñon switch, he toppled clumped, melting glass, its glowing emerald fading.

He could rest. The Portal, almost silent, the Dragones’ banter, eerily absent. The Balance, maintained.

“Some hero I’ve been--big shaman defeats Diné monster in great battle!” He scattered coals. “Guess the bebés are safe. Or were they just playing war? Quién sabe.” But he did know where some special buds were curing. Maybe he’d use some as an offering to the Holies, just in case.

§

On a comet’s tail, the Holies shrouded their gathering, facing center. “We do not celebrate ourselves,” said Ultramarine, “no reverting to mortal emotions. We shaped happenstance, with no beings aware that we did it.” Concurring, the others pulsed crimson.

Observing the little creatures scurry to their parent, every Holy held her breath, geysers frozen, mid-blast. Tieholtsodi’s family hugged and their love enveloped the Holies in pulsating turquoise, like from a birthing star.

Someone yelled, “Look, she’s losing her--”

Sky Blue’s form and color fluctuated. Into dank blue.

“Everyone, stabilize her!” Ultramarine pled.

But in stages, Sky Blue’s aura thinned, she choked, spasmed, from pining for her antediluvian family, surrendering to rejoin them. Eight Holies’ froze, silent, unable to save her.

And Sky Blue fell.

Into Earth’s atmosphere. She transmuted into a meteor that burst into gold dust sprinkling over land and sea. Much of her settled within Tieholtsodi’s grotto.

The Eight Holies gripped palms, chanting, “We laud Sky Blue and her final act.” They embraced. “We reaffirm our decisions made at the Beginning.” Grand Ultramarine plugged a tear.

The Holies regrouped to consider new prayers. Ultramarine said, “The consequences are obvious. So, what tweak might we imagine for this?” Chatter ceased when she added, “Or would we interfere with the beginning of the Fourth World?” Quizzical looks flickered on and off for some time.

§

Ignored her bleeding from the children’s tiny spikes, Tieholtsodi crushed her babies. “My aching hide glows amber from holding you two.” New gold dust brightened their home, and she could see better. “Now our grotto’s perfect!”

Her heart beat gently about how things had turned out. “I’d never have murdered the shaman.” The children stared at her. “I’d have let him slay me and prayed they released you two later. Risky, but all I came up with.” Wiping tears of joy, she flinched from her lacerated cheek.

“The shaman cast his spear like a born hunter.” Tieholtsodi had turned so it only pierced her cheek, but observers might’ve thought it fatally struck her. “Did he deliberately miss?” Not understanding her, the children scattered. “Or did the Holies intervene?”

Howls stopped her musings, but it was nothing--the children fruitlessly pushing the boulder to get at the gar. They couldn’t hurt themselves, so let them play.

“Blessed Holies, I’d never hover or obsess. Not only males possess that wisdom.” Rolling back, she laughed, teasing her babies into attacking. Until the time for some delicious gar.

§ § §

Second Place:

The Archivist

By Ricardo Tavarez, who hails from Watsonville, California, and now lives in Oakland. He has an MFA from San Francisco State and is part of La Brigada, a collective that organizes the International SF Flor Y Canto Literary Festival. His writing has appeared most recently in the anthologies, "Poetry in Flight : Poesia en Vuelo” and “The City is Already Speaking,” the City being San Francisco.

Perhaps the box rested on a music stand as she wrote her name with one hand holding a cigarette while writing with her other hand? Or it might have been after a concert in a Texan ballroom? He conceived scenarios in which Carmen was circled by fans or responding to radio host questions or standing alongside her sister as they warbled into microphones with a band roaring behind them.

It was a December afternoon. He was shelving records and cassettes when he turned his ear to a faint doorknob click. He stepped softly along the short hallway and peered around the corner. Dion scribbled on labels, shuffled paperwork and wedged notes into a clipboard.

“What record label are you archiving now?” Dion asked as he flipped through pages, waiting for an answer.

“I’m on Ideal.” He hoped Dion would be satisfied with his answer and return to the front office.

“Hmm…. Ideal? Okay,” Dion looked around aghast. “Well…can you please keep this place clean? Geez,” he muttered. His boots hammered on stairs as he bounded back to his office.

Alone again, he returned to the archiving station and pulled a reel box from the shelf. He lifted the tape gingerly, nested it in the supply column then clicked an empty reel onto the opposite side. He unwound a length of tape from the supply reel to thread it along the tape path into the capstan’s rubber pinch roller and plunged it into the playback head then guided the tape into a slot inside the playback reel base. A tiny bulb flickered green as it powered on. He turned a knob that made bulbs glow orange. Needles in two faded VU meters skittered with every knob click. He skimmed the tape box for scribbles or notes made by studio personnel. A tan note lay inside the box.

“It must be a musician list or suggested song sequence,” he thought.

Studios often included invoices, jukebox sales distribution numbers or musician names with the reels. A deep crackle filled the room; slow breathing from a singer, preserved for 50 years, erupted into a barrage of coughs, clearing their throat. He closed his eyes and imagined the guitarist plucking muted strings for harmonics while the drummer tapped on a drumhead tightening the snare slowly.

A raspy voice counted down, “Uno, Dos…,” accordion strikes revved slowly until lightning fast accordion melodies drove the band as the guitar strummed staccato chords. With eyes closed, he could see studio lights gleaming above, power cords lay tangled across the floor, and tube amplifiers glowing. The archivist memorized every note and between songs he eavesdropped on conversations whispered near microphones. Near the end of the tape, musicians chatted about who was driving the truck on Friday night. Someone asked the guitarist to pluck an F note.

He sat frozen between two eras observing the tension to keep the tape from stretching. He exhaled quietly to keep from missing faint whispers or instrument clicks. Vocalists counted down each take with: “Cut One” or “Cut Two.” Often times it was just a breath before the band roared life into the room where he sat. He couldn’t remember when the recordings absorbed him but he remembered the moment when Carmen’s voice first reached out to him from 1952.

In the spring, a new guy waltzed into the office spouting off music trivia and concert dates. It irritated the archivist when he’d stroll into the archive waxing on about a multi-track recording method, a singer’s peccadillos or launch into a lecture about song lyrics. At the last company meeting, the archivist noticed the new guy had an eye tremor before rattling off the gist of an obscure Chicago blues documentary or Delta slide guitar style. The archivist noticed the youngster’s effort to impress others with sidebars lifted from books sleeves and conversations. Once alone in the archiving room, he felt embarrassed. Not for the new guy but for the young guy he was who also did the same chirping concert dates and liner notes at parties. To have spent so much time preoccupied impressing strangers rather than feeling the warm afternoon sun on his face, sip a glass of wine and be free from the weight of opinions.

That night, he pulled out a box of 78 records and sat snuggly close to the record player. One after the other, he listened to each side and every note. He closed his eyes and drifted on arpeggios from accordions, dulcimers, violins and fell into a deep sleep. He awoke in a watermelon field and it felt like a fiery summer and his clothes were covered in fine dust. A man standing on a flatbed truck glared at him and screeched an order. The archivist was dizzy from the heat. His heart raced. He needed… water!

“¡Agua! ¡Agua!” scraped up from his throat.

He thought of cracking open a watermelon and rolled the closest melon to his lap, then lifted it to his waist. A hand jerked his belt and tipped him over. The fruit fell and rolled to a stop beside him.

“¿Que haces? ¡Te cobran la sandia!” A whisper scolded him.

A short man handed him a metal canteen. His heartbeat and breathing calmed.

“Where am I?” He asked the short man.

“Well, let me put it this way. You’re Emperor Moctezuma out for a walk.” The short man chuckled. “Sit, the sun can make you imagine things.” The short man waved a signal to the truck driver whose face contorted then punched a frustrated uppercut.

The archivist squinted into the distance. Work songs from the crew rose on the heat haze. He wiped a dam of sweat from his eyes then braced to ease up to his knees and slowly got on his feet.

“¿Que haces? Wait! You’ll…!” The short man snapped.

The short man saw his legs buckled and feet shuffle a puff of red clay. The archivist felt the crimson sun on his cheeks. A faint smile glimmered across his face as he fainted into a knot of watermelon vines. The watermelon patch faded.

Even though it had been a week since he dreamt the field and he could still feel the searing thirst. It was late afternoon when he paused to follow a sliver of sunlight inching across the wall. The beam stretched into the recesses of the room. Cracked glass from a picture frame reflected a rainbow across the room on a picture collage. The archivist walked over and stood at the collage for a moment. There were photos of buildings, storefronts, kids playing and in the last photo, a man smiled coyly.

He had unbuckled his belt in the restroom when a memory flashed. In seconds, the archivist huffed at the collage, “It’s him!” It was the short man from his dream! But how? Scribbled on the photo was a year and two faded words: “1942.” He found the archive box where it had been stored. There were receipts, expense lists and invoices. In a large envelope, he found someone’s personal collection of Polaroid’s and negatives. In other photos the short man crooned into a microphone while someone adjusted soundboard levels behind him. He founds photos of the short man playing the accordion and recording in a kitchen. Photos of the short man smiling along with two men while a worker loaded sound equipment behind them. Bold white lettering on the truck door read, “Discos Ideal.”

Was it really him?!

But how?

It was!

He knew it!

There was Armando and Paco and Beto!

He had to step out for air. From the door, the archivist drank water and scanned the sparse tree canopy that protruded from slim yard pads that hugged bungalow homes. He stepped back inside, washed his cup and dried his hands by running them through his hair. It was mid afternoon and he decided to call it a day. He had the feeling someone was watching him and couldn’t help glancing at the picture from time to time.

Once home, the archivist made tea and sat in his living room. A pocket radio on the kitchen counter rattled the news. He put the cup on a side table, reached for records and thought of Carmen. He found an empty record cover but couldn’t remember where he left the record. On the cover, a concert photo of Carmen on the sleeve caught his eye. With a puff, he opened the sleeve and found a blue paper inside. It looked new. He placed it on the table. News rattled in from the kitchen. He sipped warm tea then opened the note, it read:

Gracias por el apoyo.

¡Nos vemos en San Antonio!

-Siempre, Carmen

The curl of the C was like the one the tape box! How could he not have seen the note before? He slid the note into the sleeve and placed the cover on the record stack. Finding the note filled him with wonder. It was nearing sunset and he decided to take a walk. The faces in the picture frame flashed in his memory as he moved along the sidewalk. Across the street, teenagers roared with guffaws, smiling and hugging each other at times. Their joy felt familiar. Dusk fell with a warm breeze just as he made it back home. In the kitchen, he remembered the note while washing the teacup and decided to the see Carmen’s writing one more time. He dried the cup. Why did the note say San Antonio? Could that concert have been the reason why the men were loading equipment in the photo? He picked up the sleeve and with a quick puff parted the sleeve. He reached in and unfolded the note. It was folded differently and had a hint of perfume. He read the note, paused and looked out the window bewildered. It read:

Saludos amigo, Gracias por el apoyo

¡Nos vemos en Laredo!

–Siempre, Carmen

The archivist examined the cover for other notes. Nothing. He examined the outside of the sleeve along the edges just in case any notes were glued behind the paperboard. Nothing. Maybe the photo paper wasn’t glued right? Nothing.

That night he flipped through an atlas for a map of Texas and traced the path from San Antonio to Laredo. Concert tour dates on the cover listed San Antonio and Laredo. He grabbed a pen and ripped a page from a notebook. After San Antonio, a recording was scheduled at a dance hall in Laredo. Jokingly, he took a piece of paper and wrote:

Gracias por el disco, soy técnico de sonido

Let me know if you need help in Mcallen –A

Had anyone caught him placing the note inside, he would have blushed. The note slid into the LP cover followed by a long sigh. A talk show crackled in the kitchen. A lone bulb lit the back of the living room in the evening. He lifted his feet onto a small footstool and dozed off.

A booming thump on his door jolted him awake. Was it morning already? Had someone dropped a refrigerator on his door? He opened the door and looked down the hallway but didn’t see anyone. Laughter from people walking along the avenue filtered through the old windows. He poured some water and looked across the counter.

“The note,” he thought and paused in the narrow hallway to consider whether he ought to give in to childish curiosity and pull the note from the sleeve for some cosmic message. Just then, someone walked into the building and the heavy metal gate slammed with the usual clang. It was settled. He’d wait until morning to check the note. That night, the archivist sat in bed thinking about the concert tour, Carmen, and the strange knock on the door. So many thoughts whirled that he didn’t notice when he fell asleep.

Air streaming in between the window gaps chilled the room in the morning. The archivist eased out of bed and warmed yesterday’s coffee on the compact stove. The cup warmed his fingers. What about the note? He brushed away the idea of checking the note when he checked the time. He got ready for work instead and decided to bring some of his records to the archive. There were times between reels that he was able to look up details on LP’s in the vast archive. The train ride was uneventful as usual. Once at the archive he began by sorting and inspecting reels. It was almost noon when the intercom rang. Dion asked if he would join the office staff for lunch. Without pausing, he said he was in mid reel. Dion responded with a twanged “OK” before clicking off the line.

While rewinding a reel, the archivist puttered about the room counted magazines, inspected a photo hanging over a door, meandered to a cassette station and skimmed a recording log. Nothing on the charts stood out. He reached for the LP carrier and found the sleeve from last night. He paused when the archiving machine clicked and tape flicked round and round. He placed the cover on the desk and turned the knob to “Standby.” He stood up to shuffle through the archive box. There were faded invoices, studio musician lists and receipts. Inside a folder, pinned between receipts, he found a blue note. It was like the blue paper from last night. It was a list of names. All were familiar except for one, “Archy? Was it the comic? Was there someone on the crew named Archibaldo?

“Now that’s a real name,” he thought.

On the train home, he thought of the picture, the blue note and… the LP sleeve was on the desk! Once at home, the note was nowhere to be found. He made tea and retraced every step. Nothing. Before sunset, he crossed the avenue to walk along the lake. It felt familiar to let his shoes sink into the soft ground under the grass. Seabirds rested on scraggly roosting islands far from barreling joggers and an occasional inebriated stumbler. A heron’s marble eye burned an amber filament as it tracked him from atop a whirring power box. Warm evening gusts jostled Live Oaks. A beehive tucked in the eave of a municipal building buzzed faintly as he listened to the water lap against the rocky shore before going home.

Soon, he stood in the narrow kitchen, the pocket radio crackled Santo and Johnny. He wrapped himself in a blanket to muse over Carmen and didn’t notice when he fell fast asleep. A loud thump roused him to his feet.

“Its that thump again,” He thought, rubbing his eyes, stumbling to the door. This time he was going to catch whoever it was! He felt warm air around him and he dropped the blanket. He opened his eyes and someone thumping from inside a truck cab. Was it Paco? It was late afternoon and he stood on the back of a loading truck. Three men were also loading speaker cabinets onto the truck. They motioned for him to place them up near the cab.

“¡Sonríe!” a woman exclaimed then a flash bulb lit the back of the truck and he was able to see into the truck. There were chrome microphones and a box of record cutting needles.

“Put the wires ON that cabinet,” a muffled voice yelled through the cab window, startling him.

“Arriba!” An arm mimed a flustered motion from inside the cab.

The men stood at the foot of the truck, looking at him.

“Pues, en que trabajas que no sabes subir cabinetes?” One man asked jokingly.

The archivist looked down at the tangled wires.

“Soy archivista,” he said while winding a long cable.

“No te canses, hay mas que subir,” another man joked and surprised him with a firm pat on the back that made him stumble forward.

“¡Ay, que este archivista!”

He helped the three men load the last of the sound equipment then impressed them by winding the cables between his elbow and left purlicue paying close attention to direction the wire twisted.

“You’re a magician! The recording from Laredo is impeccable. Thanks for your help.” Armando dug into his pocket for truck keys.

“We’re cutting a full record tomorrow night. We’re lucky to have you around.” Armando said while jumping into the cab. The archivist saw him turn to Paco and say, “Carmen ya va en camino. Dijo que nos vemos con su tía.”

Armando fired up the truck, clicked a stubborn shifter into gear and heaved the machine onto the road. In the back of the truck, he improvised a snug bed of blankets. That afternoon, the truck glided along the Texas highway as the sky became a dazzling starlit panorama right before his eyes.

Third Place:

Sessions In Augmented Reality

Chicano writer Nicholas Belardes has appeared or is forthcoming in Latinx Archive: Speculative Fiction For Dreamers, Afterlives of the Writers, Acentos Review, Carve Magazine and others. He teaches for the Online MFA Creative Writing Program at Southern New Hampshire University. Nick lives in San Luis Obispo, California.

After her mother’s death, Dorota, nine years old, dreams of a dragon. Scintillating scales sway like an ash tree with glowing orange leaves. At the funeral she wears a short black dress covered in white dots reminding her she is only a white speck in the universe of the great dragon.

2.

Year after year she draws the creature’s leaf-like scales. Each pen stroke closes hollow spaces, trapping both her and the dragon in a shell of memories.

3.

Her mother’s ghost stands very still in the doorframe. Orange light ripples beneath her blue skin. “Turn off the light,” her ghost-mother says.

4.

Eighteen now, Dorota sits against the wall of her bedroom, opposite the hanging round lantern with the broken bulb. Her moleskin journal rests on the floor. She opens it and begins to draw, using the nightlight her mother Eleadora gave her.

5.

Eleadora’s ghost accompanies Dorota to the tea garden in San Jose. They ride the train around the storybook maze. Dorota knows if she tries to touch her shimmering form Eleadora will leap off the train. Eleadora points out the strangers:

“You see that old man. He has the flat face of a dog with no snout. You see that boy on the bridge staring at koi? His profile resembles a fish and his arms are short like fins.” She points out fairytales too. “This one’s a rabbit. That one’s an aardvark. She’s cake frosting. Let’s go eat cake.”

And so Dorota does.

6.

Dorota is biracial. Her white father, James, knocks on the bedroom door, asks about her boyfriend.

She wants to tell him that her boyfriend Albert is like a moon. Grey. Lost. A distant dead planet. A piece of rock that wants to found. Albert hovers in the candy dish of her solar system.

Her father stands in the doorway where Eleadora also hovers. “Why were you in the city?” he asks.

“To draw and read.” Dorota knows he just wants to be a part of her life. She tells him about an orange-and-yellow skirt she saw in a downtown window. She doesn’t really want it.

Her father slips a letter out of his back pocket. “I’ve been holding onto this for nine years,” he says.

It’s been nine years since her mother died.

Nine years since she was nine years old.

He sets the letter on her desk. The paper glows muddy grey in the dark.

7.

Albert holds a photo of Joanna he’s been carrying for several weeks. He tucks it in Jeet Thayil’sNarcopolis, his favorite book. He read Dorota the prologue, “Something For The Mouth,” over and over.

8.

Dorota tries not to get jealous of Joanna. It isn’t like Albert knows her. Dorota thinks he’s put Joanna onto some phantasmal pedestal where Dorota will never be unless she becomes a missing fantasy too.

9.

Albert found the photo of the missing woman nailed to a lamppost in the Mission District. Now he carries Joanna everywhere. Her narrow black face shines at them.

Dorota wants to hold the photo.

She can’t bring herself to beg, let alone pry the photo from Albert’s fingers. She knows she can. When they have sex she doesn’t mind his effete thrusts.

10.

Dorota asks, “Do you think you know where Joanna is?”

Albert sips bourbon. He turns the glass as if he doesn’t want to drink from the same rim twice.

Dorota thinks about how always she acts like such a little girl around her father. She’s sick of herself, sick of home, sick of her mother’s ghost following her around yet not wanting to be touched.

By the time Dorota is aware, the bartender is climbing on a chair, reaching for the lower lip of a mounted moose head, shot in 1897 by a hunter named Robert Smith Heffernan, whose own black-and-white photo is less life-like than the head of this creature.

The bartender is being directed by Albert, who points upward.

“The mouth!” Albert’s voice is shrill, audible. “There’s something in the mouth!”

11.

The bartender is beautiful in the red light, eyes like dark stars, neutrons sucking in the light. Dorota is glad the bartender hasn’t fallen as she reaches in the taxidermal mouth, pulling out a white slip of paper.

Albert explains they’re on the trail of a missing woman named Joanna. He shows the bartender the photo from the lamppost. Has she seen her? Maybe she’s a regular customer?

A hint of light flicks in the bartender’s eyes. “No.” She shakes her head. “Is this a game?

12.

Dorota isn’t about to give up. “I’m down for Z & Y if you tell me what that was all about back there.”

“We just ate,” Albert says. “It’s a note.”

“I can see that. From who?”

“Okay. Let’s get to BART,” Albert says. “I’m freezing.”

Dorota uses a felt pen she keeps in her purse to sketch his silhouette in the alley, face half-lit, long puddles stretching around his feet. She pays close attention to his hunched shoulders. She draws a line of continuation up to the corner of a fire escape where plants drip water from the recent rain. Then she follows the line to reflections of walls, windows and neon, blurring the thin layer of oily water. Finally, she draws a sheet hanging wet from rain along with graffiti markings on the wall: KULTURKAMF and PARADISE NOW.

13.

A dragon towers in the alley, pulsating, lit from inside, a giant lantern of scales.

Dorota imagines the beast and considers going back home. Her father wanted to talk about the letter. She’s not ready to confront the blood on the page.

“What are you doing?” Albert asks.

“I told you,” she says, drawing again. “I’m chronicling your mystery.” She knows he’s just another set of abstractions. She can draw that.

14.

“The Geheimnisse,” Albert’s muffled voice echoes through his gas mask.

Dorota has seen the stencil lining walls in both the Oakland and San Francisco Chinatowns. She first saw it near the side entrance to the Furnace of Beautiful Writing. She likes to read there because so many books have been incinerated in its oven.

15.

Albert babbles about the experiment in the tower, the threat of implants, Kulturkamf. Mysterious calls at coffeehouse phone booths. She picks up a French novel about memory and wonders if a copy had ever been burned here.

16.

The day they bought the gas masks they watched experiments with sound through oscillators. Sound-field characteristic studies, chaotic oscillators, sound-bending, embeddable tech implants. Sound benders and biohackers showed off their scars, using their implants to make digitized sound react to gyrating around wildly like some kind of fucked up cyber-ravers. Every smart phone went crazy. In the middle of it was Professor Piot. He said the Geheimnisse was something tangible. Dorota half expected Eleadora to appear.

17.

Albert is an apologetic bug in his gas mask. Dorota’s headlamp lights up a wall. Around her feet an inch of water trickles past. She thinks she sees a salamander or a frog. Its body is dragon-like, flaming. She’s far in the tunnel, having squeezed through the grate on the side of a hill mostly covered with pine trees at an abandoned water station. She studies the creature, draws gestures of it in her journal.

18.

Q & A with Professor Rudolph Piot. Interviewed by Marion Little for Health & Rumor Magazine, Oct. 13, 2027.

Health & Rumor: You’ve launched an experimental course. You’re calling it Sessions in Augmented Reality: Blending Realism & Fantasy. There are no course materials. Is this class a sort of game?

Piot: I don’t call education a game. Not at all. One of our national leaders recently said, “Life as you know it on Earth is at risk.” I think we all feel this fear in some way. What happens if we’re forced to go out into the world and confront contextual boundaries? What happens when we learn from society by putting our hands in the fire? People slip into augmented realities every day, aware that fiction and fantasy are already a part of their communication.”

Health & Rumor: Do you worry about your students?

Piot: That they would discover the truth? The people participating suggest there’s a reality that is more than convincing than everyday life. They’d rather be led down a rabbit hole than into a NIKE store. Is that bad? Just because some of the people searching for answers are connected to me through the university doesn’t mean there isn’t validity to what’s happening.

Health & Rumor: What is the Geheimnisse?

Piot: Quite literally it means “secrets.” Layers upon layers of realities are being peeled away by some of the most brilliant young minds of the city.

19.

Sirens race the paved hills as Dorota pins a drawing to a bulletin board with a grey tack. There’s no telling which street they’re wailing their shrill songs. She inspects the spaces between buildings. Could there be winged creatures atop Coit Tower? She imagines beautiful women luring ships from the deep black Pacific while at the same time warning of fatal lethargy.

Dorota has drawn the man with an African accent they saw on BART surrounded by passengers in masks and gloves. He’s pleading. Crying. His child is crying too, begging for daddy to make all the people stop looking at her.

“Will you all please stop this madness,” he cries.

Dorota wants everyone to see the drawing, to know the panic on the faces of the transit passengers. She licks the wetness from her bottom lip as if frozen by the ghostly presence of Eleadora running her blue fingers along the sheets.

20.

SAN FRANCISCO, CA -- A hoax story about San Francisco State professor Rudolph Piot dying in a Bay Area tunnel on Saturday has duped internet users, city officials, and media sites who reported on the professor’s death.

A group of urban explorers alleged that Professor Piot was found dead in a storm drain tunnel made popular by the Suicide Club in the 1970s.

San Francisco police officials cite a popular augmented reality game as the culprit.

“We are certainly not aware of anyone dying in a tunnel,” said Officer Donny Youngfellow. “But there are Hispanic gangs we’re clamping down on this moment spreading disease and lies among Californians. Not only them. Immigrants are swarming the tops of Amtraks in the middle of the night, clinging to trains flying eighty-five miles per hour, trying to escape San Diego up the Pacific coast.”

Officials claim the professor was found grading exams at his home in Oakland.

21.

Dorota thinks of her drawings now pinned to a downtown San Francisco bulletin board. Will rain disintegrate the paper? Wash away the colors? She wonders if this is Joanna’s fate. Will she altogether disappear from both present and past?

“The note says to go to the tunnel again,” Albert says over dinner.

Dorota drops her spoon, pushes the bowl away. She thinks of the letter again, wonders if Eleadora will crawl from it, pale and blue, heaving herself solid into this world, like some kind of hybrid from the experimental meat farms.

22.

The smell of burnt fish crashes into Dorota’s nostrils. Charred remains coat the sink. Eleadora could cook fish, unlike her father who burns it every time.

Dorota remembers the mouthwatering kind of tilapia tacos that filled her with love and energy before she scooted out the door to school as a child.

23.

Dorota wonders if she will ever see dragon fire emanate from the mouth of her ghost-mother.