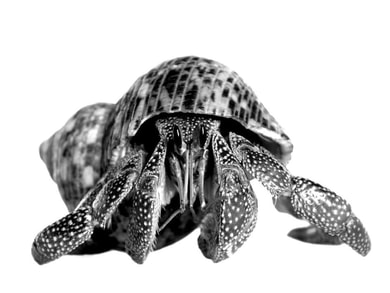

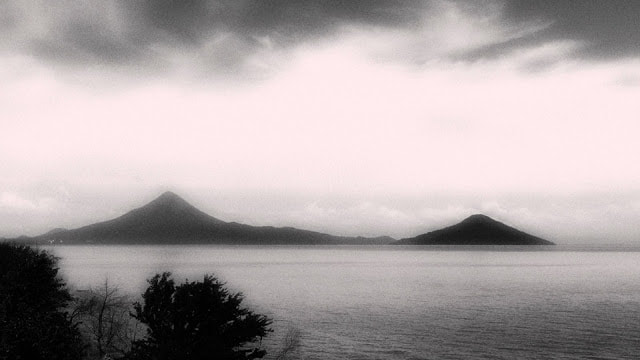

Beyond the Cave by Kevin M. Casin Bran arrived at the cave. The shadows held by the chalky stone frame played with him, shaping into the fairies from his dreams. Maybe they were eating the travelers. Nic grunted as he climbed onto the shale slab. He rolled and lithely sprung to his elvish feet. “Why the gods thought to bring us together, I will never understand,” he grumbled. He tossed his loose brown hair. His brown hands brushed charcoal dust from his caramel leather vest and adjusted the bow and quiver on his back. “Bring me to my death, he will. Just watch…” Bran wrapped a fleshy arm around Nic’s slender shoulders and said “see, it wasn’t so bad!” “Be careful, Bran,” Nic said. “Your research won’t save up. We slipped past the guards. No one is coming if something goes wrong.” “Oh, stop worrying. What’s the worst that could happen? We’ll look around and go home.” Bran looked around for bone, carcasses, anything that might show signs of a feast. He found none. If they weren’t eaten, then maybe captured and held against their will? “Since you’re so worried, I’ll go in first,” said Bran. He took his birch staff into his brown hand and slipped the vine band off his chest. He looked back at Nic with a smirk, “and make sure everything is safe before you come in.” Darkness washed the world from Bran’s skin. He held his staff tight with both hands. A tingle entered his fingertips. It felt like magic. Maybe there were fairies. But he wanted to see them. In the shadows, he searched for the portal to their world, the one he had traveled to in his dreams since he was a child. He hoped to find the glass structures that pierced gray clouds. Was the silver-eyed man there, and his haunting robotic speech? How about the orange man with green tendrils, the one who soothed him? “Maybe some light will help.” He set his hand over the branches of his staff. He felt them curl under his palm, but he before he could speak the spell, Nic interrupted. “Bran! Come look at this!” Bran rushed to the near end of the cave—he realized was more of a tunnel. Nic gently cupped a pale, orange hermit crab. “That’s not from the Otherworld!” Bran huffed. The crab scuttled into its shell, bunched into a fist. Nic laughed. “They never did like you. Maybe there’s something to learn here. Not everything has to be otherworldly. Sometimes a crab is just a crab, and that’s okay. Pay attention to what’s real, Bran. The rest will always work itself out.” Bran rolled his eyes. “When did you get so old and wise?” A chilled breeze knocked Bran’s thick, black curled hair onto his face. The roar of the great sea called to him. He looked out over the cliffs beside Nic. “What is that?” Bran asked. Perched on crags, Bran saw a castle. Pointed towers, like fangs biting into unfurling storm clouds. Thick, dreary walls sprouted from the algae-green rocks and stabbed the central tower. An eerie chill seeped into his skin and pinched his nerves. He hated the feeling of insects creeping over him. A crack came from the cliff behind him. The rock under his feet tore away from the mainland. Nic knocked Bran down, hoping to carry them over the fissure. But he failed. Bran braced for another sensation he hated—the thrill of falling. He waited for the hands juggling his intestines. It never happened. Bran rose to his feet with Nic’s help and the cliff faded away. Bran realized they were gliding toward the castle. Nothing but air and certain death lay beneath the levitating boulder. Bran balked at the vacuum. He hugged Nic. As he fumbled at the weight, Bran prayed to the fairies, pleading with them to carry them safely over the carnivorous sea. The cracks aligned perfectly. It hovered in place as Bran and Nic stepped off, then pulled away, drifting back to the cliff. As they climbed a stone-carved staircase, Bran felt the vibration generated from the thrashing waves crawl up his bones. He peered over the rough edge and realized they were swaying. Bran glanced back at Nic and said, “I think a good wind will knock this whole place back into the sea. But I guess we’re stuck here for now.” Bran stood before a wrought iron door with bolts about his size. On its own, the door creaked open slightly. The castle exhaled stale air, like the musk of a thousand-year tomb. The breeze lifted dust from the stone slabs, taking hazy human forms, like meandering ghosts looking for their true home. “Fairies,” Bran exhaled enthusiastically. People—some human and others alien—skittered around him with apathetic faces and in clothes outside the custom of Ulamar. Men in long-sleeved tunics with a cloth folded over their chests—"suits,” the word came to him, but its origin was a mystery to him. One of these men strolled up to him. Bran shuttered. His youthful face carried silver eyes that held the weight of ages. He didn’t seem as scary as he had in his dreams. Bran had power here. He wasn’t going to be intimidated. “I am Bran, protector of Ulamar and heir to the throne. I don’t recognize you, or any of these people as my subject. Where are you from?” Bran assumed a regal voice, dropping his tone by an octave. The man opened his arms and said, “welcome to the House of All Worlds. I am ARI: Alternate Reality Integrator.” Though his sentences ended with a flair, his smile was empty and strained. “I am tasked with carrying out our company motto: All things are possible. Is this your first time?” Bran glanced back at Nic, who surveyed ARI with an incredulous eye. “Are you…a fairy?” Bran asked, stepping close and examining ARI’s hazy aura. “Fairies? Oh no, sir. I’m afraid you may be experiencing Envoy sickness. Oh, not good. Must decontaminate quickly. This way, please, right away.” ARI extended his arm and guided the way into the dilapidated structure. Bran looked to Nic, whose eyes held worry, but nodded as if to agree the way seemed safe enough and this was there only way out. Their only option was to find a way out that was different from the way they came. Bran walked into the castle, hoping it held some answers. Though the decay faded as they entered, the gloom never left. Sunlight fell from the ceiling—the only light source—down a well-formed by a spiraling white staircase. Beyond the stairs, glass cages scaled the curved heights. Like an egg, or a gherkin. People scurried around, vanishing behind metal doors that slipped into dark, bland walls. A lonely banner draped from the far wall with a symbol—a cat sitting on its hind legs, a small “S” on its chest, and a giant “U” behind it. They reached the center of the space. “Welcome back to Ulamar. Here, in the House of All Worlds, we can take you anywhere you want to go. With our convenient and affordable prices, we can help you visit any multiverse.” ARI spoke with an unnatural enthusiasm. Bran considered it strange how the name of this place was the same as his kingdoms, but a nearby man caught his attention. Green roots dangling from his carrot scalp over broad shoulders. A silver uniform intimately shaped his beefy torso. The cat emblem on his peck. A scowl pinched his oily cheeks. He tapped an invisible pane, each yellow symbol vanishing with a flash under his fingers. The man’s jaw dropped. He recovered quickly and returned to his work. Bran thought the reaction was strange. And slightly insulting. Bran wasn’t aware of any orange people in Ulamar. He let it go. ARI guided them through a broad doorway at the back end of the egg-shaped space. Aisles of glossy, white saucers encased in cylindrical glass sprawled away infinitely. “What are these?” Bran said. ARI led them along a corridor, then stopped beside a vessel. He raised a hazy hand. “The sickness…correct. Memory triggering may help. “Here we keep out state-of-the-art Quantum Envoys. An array of our safe, proprietary krypton-xenon lasers vaporize customers into elementary particles and funnel them into our Alternative Reality Capacitor. By tapping into the quantum strings, we can digitally recreate you and your loved ones anywhere in the multiverse. Then—thanks to our wonderful technicians, of course—we can bring you right back home with the push of a few buttons.” ARI pointed to an orange-skinned man beside a nearby Envoy. The same man from earlier. Now with an inquisitive grin. Bran smiled at the familiar and attractive technician. At twenty, traditionally men in the kingdom found a wife, but he never felt that life suited him. He’d settled the reason on his insatiable need for adventures. Now, as he stared at the man, he reconsidered. “Could this be some type of magic?” Nic asked. Bran tensed as he approached the Envoy and the technician. “Yes,” ARI replied, “in this world, I believe the natives would refer to this work as ‘magic’. Ulamar knows this as physics. Are you familiar with Schrӧdinger’s Cat theory? No? Well, never mind then. Now, here are your neural networks from the moment you entered the House…” With an opaque hand, ARI swatted the air. Lines webbed into circles across a hazy brain. Bran fought back tears, recalling the day his father slaughtered a sheep right in front of him. He wanted to teach his son to fend for himself, to be a man. So, he set the brain in Bran’s hands. Hypnotic green and red waves intensified as they reached the circles and distracted him from the memory. “Obviously magic,” Bran concluded in his head. “These two quadrants are unlinked,” ARI traced a line between two circles. A black hole broke the currents. “The memory centers of your brain. The informational flow is either impaired or repressed. A common side-effect of the transport. Not to worry. When the brain lingers in another universe it must adapt and form new connections, synapses, like these,” ARI marked another line with intense, red swirls. A hand rested on Bran’s arm. Nic guided him away and whispered, “I don’t see any way out, but I say we try to make a run for it. I have a bad feeling. We need to go.” “I’m afraid we can’t let you leave in this condition, Nic.” Nic twitched and held ARI in a deadly glare. ARI stared—his calm, faux-jovial expression unmoved. “I believe your syndrome is severe,” said ARI. With a wave, a new network appeared. The map is framed on the memory center. Red waves flowed naturally into the two circles. No black hole. “Connection found…Memories missing… Deleted. No leaving, I’m afraid.” ARI quieted for a moment. His hollow, silver eyes scanned the network. The technician stepped away from the Envoy. His pace slowed as he neared Bran. Suddenly, ARI shot erect. His head thrashed and his voice changed. Like iron rasping a metal drum. “House breached…execute…sterilization protocol.” The technician wedged between Bran and Nic, then grabbed their arms and said, “we’ve got to go now!” # ARI’s hysteria faded as Bran raced down the corridors, guided by the mysterious technician. He passed through a new door and burst into a hallway. Glossy pale walls with silver lines slicing down the corridor greeted Bran with a meek, yet more lively welcome than the lobby. Here, the light came from strange, luminous ropes in the ceiling corners. The hall curved and as he turned the corner, he clashed with an orange woman. He knocked down unknown objects from her metallic trays. Bran tried to frown as he swept by her, but he wasn’t sure if she caught it. He heard the objects crack as Nic’s heavy steps smashed against them. Bran followed the man, who brought them to an elegant staircase of sterile white that coiled around a tiered, crystal chandelier. Lanky creatures with cerulean skin clothed in white silk, beaded with grey pebbles seemed to hover over the steps. “Water fairies clad in eroded limestone,” he recalled from the old stories. An orange woman in a silver uniform barred their path to the stairs. Bran grinned in fascination, disregarding the odd metal object in her hand and her threatening grimace. The technician yanked him away, through yet another sliding door. This time, Bran came to a cold, metal room. A terrible place to hide, he knew, but before he could offer his thought, the technician tapped on the wall and the doors closed instantly. They were moving. Almost falling. “What is going on?” Nic slammed the technician into the wall and held his forearm on his neck. The man didn’t fight back. “You have to leave. A native can’t be in here. They will kill you.” The words dripped like fresh cream from his lips. “I’ll kill you first.” Nic drew an arrow and held the sharp edge by his throat. He pressed enough to draw blood. Bran tensed and threw his arms over Nic, pulling away. The wall caught them, but Bran didn’t let go. The embrace comforted him, and he sensed it helped Nic. A sea flashed in Bran’s mind. A vision. Still waters. A weight pinned his hands and body to pearl sand. Passion on his lips. Braids tickled his cheeks. Green. The face. Duran. Bran snapped back to reality. “I don’t think he wants to hurt us, Nic. I know him,” Bran whispered. He felt the calm air from Nic as his breath deepened. Bran held onto him. Like he might lose him. “We do know each other, but more of that later. I’m Duran, Senior Quantum technician. In all my years with Ulamar, no native and customer have bonded so much. Every time Nic looked at you, the map turned red. He was thinking of you, Bran. Your memories together.” “He’s been my best friend since we were kids.” “Kids?” The room jerked to a stop and knocked everyone to the floor. Duran shot up, waved his arm over the wall, and yellow symbols appeared. They faded as he tapped them; replaced by more. “Damn! They turned off the elevator. Luckily, we stopped just under the 100th floor. We’re close to the tunnel.” He swatted the characters away and produced a slim rod from his pocket. “Step aside, guys.” He aimed it at the ceiling and a light beam shot from the tip. Bran watched in amazement—it melted the metal into a ring. It fell with an empty thud. Duran tucked away the rod. He set his hands on his knees and lunged. “Come on,” he said to Bran. He sprang through the hole with Duran’s help. He landed in a dark, musky well. He followed a thick chain holding the metal box as it curved along the walls. Nic appeared, startling Bran, then helped Duran. He patted away the dust away. His hands caressed his grey clothes, moving from his chest to his waist. Bran followed with his eyes, memorizing each space. Still waters. Pearl sand. Passion. Greece. More visions. Bran stood before a broad door the exact size of the metal box. He hoped it might open for him, but it didn’t. Was the fairy magic even real? Or did they take it back out of spite for running away? “Step aside, Bran. I got it.” Duran carved a hole about his height. He nudged the slab and it fell away. Once through, he held out his hand, waiting for Bran to take it. But Nic came between them. As he drew his bow, he glanced at Bran and said, “Brawns before brains.” He winked and went ahead. Then, he signaled for Bran. The bright light bathing the glossy walls blinded Bran. Squinting, he scampered down the empty, doorless hallway. No, it had one door, Bran noticed. At the end. Beyond the door, a rusted staircase descended into a sewer. Footsteps echoed faintly. Bran examined the stairs, hoping to glimpse the source of the noises. The flights curled to a point, like a black hole in the sky. “Down here, Bran. Just a bit more and we’re out of here,” Duran insisted. Bran stepped close to Duran. From afar, his face held a spry youth, but now, wrinkles crept into the corners of his eyes. Each line is a story. Piece of Bran’s story. He met Duran’s emerald irises, consumed by a swirl of anxiety and despair. Yet, peering from behind those emotions, hope. Life. Fairy magic set into his nerves, sparking a bulb. One thought extinguished. Now, teething with new life. “Duran,” Bran whispered. “I loved you, didn’t I?” # A smile pinched Duran’s oily cheek. Bran stroked the dimples with an olive thumb as he welcomed another vision. Bran awoke, desperate to experience the latest in Ulamar technology—the Envoy. He threw what semi-clean clothes he had on the floor and headed to the newly built House of All Worlds in New London. The House—housed in the repurposed Gherkin building—was the final wonder of the world. He declared no one should bother looking for another because none stood a chance. Until a Karian took his admissions ticket, ripped it in half, and smiled. “Welcome! I’m Duran, I will be your tour guide today. Looks like it’s just us for today, shall we get started?” Bran nodded speechlessly. Duran walked ahead, gesturing at captivating machinery, except Bran never looked at any of it. His attention fixed on Duran—and resisting the urge to survey the uniform revealing his beefy form. When the tour was over, Duran brought Bran to the employees’ lounge, insisting it was the final stop. After he gathered his belongings, he turned to Bran and asked, “Are you asking me out or what?” Bran mustered a warble and a nod. Duran laughed and led them back to an Envoy. “You are going to talk to me on our date though, right? You’re cute and all, but I need some conversation.” “I’m sorry. I’m just nervous. I’ve never done this before.” “Date? With a face like that? I find that hard to believe.” “Spend so much time with someone so unbelievably beautiful. Like a fairy.” Duran laughed. “Lucky for you, I like fairies. So, I’ll take that as a compliment. Come on. Let’s go somewhere special. My treat.” The Envoy sears the flesh from Bran’s bone. A prick, then nothing. Light as air, a sea breeze, his essence, his molecules, his form, condensed on a beach. “In 20th century Greece,” Duran explained, “before Columbo buried it in ash, before the Human Reconstruction after the Nuclear Wars, before the Karians ever stepped on Earth, before the Quantum breakthroughs.” Bran laid on the pearl sand. Basked in Duran’s sun-kissed glow. Passion on his lips. And Duran in his arms and heart. Bran believed a life, a world, a whole galaxy without Duran seemed impossible. In those days. Before he ended up here. Now, Duran was a stranger, a kind stranger, but nothing more. Though his heart told him differently. A boom came from above. Bran descended and arrived at a long, damp tunnel. Like the cave he now questioned. Was it real? Was anything in the last twenty years of his existence real? He felt a hand on the bend in his lower back. Nic offered a reassuring glance. Nic…was he real? Another boom echoed. Bran slowed as he ran down the tunnel, avoiding a fall on the slick, sandy mud. He focused on a growing light. It banished the shadows. It revealed the truth. It held the roar of the sea. Sunlight beamed intensely as the afternoon bloomed in a cloudless sky. It warmed Bran as he emerged onto a stone table, jutting over the raging sea. Nic and Duran ran ahead and peered over the platform, each searching for something. Nic almost crushed a hermit crab. It hopped back into its orange shell. Like the one on the cliff. He doubted if it was the same one. Was it following us on this adventure too? Bran sat beside it, feet under his thighs, and observe the little crab reappear. Its eyes wiggled, studying Bran, judging his potential for harm. Bran wondered that too. Nic didn’t belong in the House. He belonged in Ulamar. Bran belonged there too. His heart told him so, but his mind urged him to reconsider. Bran picked up the crab. He set its curled legs on his hand and waited for it to emerge. “What do you think? Go with Nic or Duran. What would the fairies want me to do?” A leg twitched. “Bran! Come look at this!” Duran waved. Bran sauntered over with the crab gently cupped. Duran pointed to a winding stone staircase. It ended at a pale patch of water—a sandbar. A hand rested on Bran’s shoulder and turned him toward Duran. “Tell Nic he can climb down and swim to shore. They won’t follow him and risk revealing more to the other natives.” Duran grinned. Licked his lips, prepping for a kiss that never came. Bran didn’t meet his gaze. His head shook gently. “My world is so much better with you in it. I thought I’d never find you.” Duran presented his plea. “Couldn’t I just travel with the Envoys? I can be part of both worlds.” “They’re tearing this place down. A native, unfamiliar with this technology, entered. Even with Nic gone, they’ll destroy it. If he can find it, so can others. They might even rebuild on another part of this world. Business is business.” Bran’s heart fluttered with debate. He felt love for Duran—at least his mind told him he loved Duran—but his feelings for Nic were different. Blood brothers. Bran just couldn’t leave him. His heart wouldn’t let him. “He’s just some guy you met here. Those memories aren’t real. They’re just replacing old ones, like double-exposed film. I’m real. Look. Feel.” Duran set Bran’s shaking hands on his chest. “We grew up together. Those memories are real. I think I remember what happened. The day I left New London, heading back to Greece, something happened with the Envoy. I felt the sting of the lasers, but I didn’t feel like air. It felt like water. I woke up in my mother’s arms. I was born here…twenty years ago.” Bran glanced over at Nic, turning through pages of memories, every story refreshed. The crab tickled his palm. He peered through his fingers. Its legs were moving. Suddenly, Nic jerked toward the tunnel. Bran looked up. Blood spattered from Nic’s chest. He dropped the bow. His hand cradled his shoulder. Bran set the crab in his pocket and rushed to help. While Duran ran to stand before three, armed silver-uniformed agents. “Stop, wipe his memory, and let him go. He won’t hurt anyone.” A wisp of sea spray twisted into a human. “Hello, I am ARI: Alternative Reality Integrator, and spokesperson for Ulamar, Incorporated, where all things are possible. Unfortunately, your request for memory deletion was denied. For the safety of our customers and employees, the native must be eliminated. Please stand aside.” Blood covered Nic’s pallid hand, pooling under him with each drip. Bran felt shallow breath beneath his hands. “But this whole place will be destroyed. He can’t follow anyone,” Bran pleaded. “No negotiations authorized. Please stand aside.” An agent approached Duran and pressed the gun barrels to his chests. Resigned, Duran followed her behind ARI. Another came for Bran, but he refused to step aside. Bran slipped an arrow from Nic’s quiver, lunged for the bow, and with a fluid twirl, he killed the agent. Bran had never killed anything or anyone in his life. Was he a man now, like his father wanted him to be? The other two averted their aim from Nic. Each held the triggers under their fingers. Each glared in vengeance. “Murder is not permitted on Ulamar property. Surrender or be terminated.” Bran rolled, but his hands failed to pinch an arrow. He rose to his feet, chin high, and stared into ARI’s dead, silver eyes. With a cold grin, he said, “Fire.” “So much for fairies.” Bran thought his last words as he closed his eyes. One shot…a second… Death didn’t sting. Each bullet shoved him back until the platform slipped away. Heavy, but painless—was he carrying something? Falling again. Like the elevator. Hopefully, the sea was just as kind. # A stab woke him up. Bran reached for his leg. A bulge twitched and he remembered the crab in his pocket. He pulled it out, then set it on the pearl sand. A foamy ripple tickled his fingertips. Bran sat up. Alive. He studied his body, searching for wounds, but he found none. But they shot him…right? This day was full of surprises. The crunch of crumbling rocks captured his attention. It gazed out at the crags. The pillars supporting the castle snapped, devoured by thrashing waves. Unpulverized chunks of the tower fell into the sea. The castle fade into memory. Nothing more than eroded rocks. “Good riddance,” Bran cursed. Bran looked down. The hermit crab was gone. He followed its foot pricks to a patch of bloody sand, to Nic on his back dying. Bran swept away lumps of coagulated blood. Three bullet wounds festered. He tore away his shirt, tearing the fabric into pieces. He bandaged the holes, hopelessly. Nic wasn’t bleeding any more. He couldn’t. His eyes opened slightly, and he mouthed something. His lips were too weak to understand. He felt the sentiment though. He knew Nic well enough to know he was sending his last drops of love in his direction. Bran laid a kiss on Nic’s forehead. He rested his head on Nic’s cheek and felt the feigning air caress his chilled skin. Nic was beyond saving. He returned all the love Nic always gave him. “Maybe it will help him, wherever he’s going,” Bran muttered. He prepared the grave away from the voracious sea. It would not take Nic for as long as Bran lived. His promise to Nic as he laid him in the shallow grave—never forget. In its fulfillment, he would devote a day each week to visit, to tell me all about his adventures, to bring him a rock to place on the grave—a tradition to remind the dead they are remembered. He searched for the hermit crab. He wanted to set it on the grave, give it a chance to remember Nic. It knew him too, after all. He saw the bobbing orange shell a few meters away. It wasn’t crawling away. Bran strolled to it. The crab was nipping at a white box nestled in the sand and nudged by the ebbing waves. A message carved onto the lid: “Save him.” In the box, Bran found a syringe between the black foam. The label read Mendflouramide. Bran recalled the medicine, its miraculous ability to mend bones and wounds. Many credited it with saving countless lives in the Great Pandemic. Others believed it sparked the Nuclear Wars. Bran grabbed the box and the crab and raced back to the grave, furiously shoveling the sand with his hands. Hope in his heart. He stabbed Nic, watching the blue liquid ooze into his pallid arm. He sat on the sand like a rag dog and marked the passing time with the swash. With each beat, he prayed it wasn’t too late. It had to work. Nic coughed. Paralyzed in disbelief, Bran watched water trickled from his mouth with each exhale—the wounds were gone. Scarred by fresh skin and bullet shells sprawled on the sand. He didn’t dare move. He avoided any disturbance of the cruel dream. But after observing Nic heave the last drops, he knew nothing was more disturbing and he didn’t care if it wasn’t real. Joy burst into Bran’s face. With all his weight, Bran threw his arms around Nic and wrestled him to the ground. He squeezed the renewed life from Nic, determined to never let him go and return all the love Nic ever gave him. Nic howled with laughter. Bran let him go. He laid on the sand beside Nic and together, they watched clouds drift in peaceful silence. Bran thought one looked like a man with silver, aged eyes. “So, what happened with the castle? It’s gone…” Nic rolled onto his side. He picked up the hermit crab, letting it rest on his palm. Bran rolled over, his head in hand. “The fairies in the rock took it back to the Otherworld. That’s all we need to know.” Nic rolled his eyes with a head shake. “Still with fairies. I guess they were real after all. Are we going after them again? That was kind of fun.” “Nah. Pay attention to what’s real, a wise man said to me once. And everything will work itself out.” Bran reached for the crab. It didn’t recoil. It tickled his hand and crawled into his palm. He held it to his face. The shadow of Nic’s smile in the background. “It’s not afraid, I guess. You’re growing up.” Bran enjoyed their new time together. As the sun faded, they gathered themselves and headed back to the mystic gate and the Kingdom of Ulamar.  Kevin Casin is a gay, Latino fiction writer, and cardiovascular research scientist. His fiction work is featured in If There’s Anyone Left, From the Farther Trees, and more. He is Editor-in-Chief of Tree And Stone, an HWA/SFWA/Codex member, and First Reader for Diabolical Plots and Interstellar Flight Press. For more about him, please see his website: https://kevinmcasin.wordpress.com/. Please follow his Twitter: @kevinthedruid.

0 Comments